The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

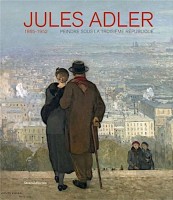

Jules Adler, 1865–1952: Peindre Sous La Troisième République.

Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2018.

236 pp.; 111 color illus.; biographic chronology; bibliography.

€ 25

ISBN: 9 788836 636327

One of the most neglected artists at the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has been Jules Adler (1865–1952)—until now. The recent exhibition of his work in the museums in Dole, Evian, and Roubaix (France), and the publication of an extremely comprehensive catalogue that functions as if it were a definitive book on the artist, emphasizes that Adler’s place in the creative pantheon is destined to change. Adler will now step out of the shade, to which he has been relegated for decades, so that his extensive contribution to naturalist painting can be seen, absorbed, and studied. The reasons for the neglect of this artist are not difficult to comprehend: he never followed the tendencies of the modernist avant-garde; and he refused to be shaken in his belief that naturalist painting was the one true way to assess the world he lived in, so until his death in 1952 Adler recorded the people of France. His production often focused on the masses who lived in the city, pursuing their activities as they went about the ordinary concerns of their daily lives. Twenty-first century art historical scholarship has contributed a more inclusive methodology, incorporating a welcome understanding of naturalism as another approach to creating art in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This publication demonstrates that Adler was a compassionate recorder of life in large and small compositions, which occasionally received the attention of the government during the Third Republic.

Seeing Adler’s work in this fresh context is strongly reinforced by the numerous substantial essays in this publication. Each essay is the work of a scholar who is intimately aware of his work, starting with the first essay by Laurent Houssais, “De Luxeuil au Seuil de L’Institut” (From Luxeuil to the Threshold of the Institute). Beginning with his early student works, many demonstrating his superb mastery of drawing from life, Adler’s activities at the famed Académie Julian in Paris are noted; there he studied with such academic artists as William Bouguereau (1825–1905) and Tony Robert Fleury (1837–1911). This training allowed Adler to enter the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1884 where he obtained an Honorable Mention for figure painting after antique models (17). To illustrate Adler’s training, the book includes images of his powerful academic nudes, as well as a drawing after an antique cast that was produced under the tutelage of Bouguereau. By the early 1890s Adler was exhibiting at the Salon des Artistes Français where his painting of La Rue was purchased by the government who sent it to the museum in Castres in southern France. The theme signaled Adler’s interest in one of his most significant subjects—painting the people in the street. The author demonstrates that Adler was interested in showing work beyond the Salon, pointing out that the painter sent his work to exhibitions dedicated to works by artists from his home region (23). Houssais also makes it clear that Adler’s creative work was balanced by something else: he was a dedicated teacher. He not only contributed to the training of the young, but also was interested in seeing that adults were encouraged to do creative work. As tastes changed Adler remained steadfastly dedicated to his ideas of naturalism; he was nominated often for membership in the Institut de France, but each time he was overlooked in favor of others. As an introduction to Adler’s career and work this is a useful and necessary section.

The second essay, “Adler, ‘Artiste Juif’” (Adler, Jewish Artist) tries to examine how Adler’s heritage influenced his work. But this is very difficult to do since he did not create compositions that were decidedly Art israeliste, preferring to reveal his Jewishness by increasing his humanitarian themes. La Mere, a canvas from 1899, for example, shows a young mother struggling with her child while walking the streets of a city as two men converse at a bar that serves absinthe. Adler was never one to stress images of a pogrom; his Jewishness was not blatantly emphasized. As the author notes, Adler was one of the first generation of Jewish painters to show their works in group exhibitions in Berlin and Palestine. Questions still remain: what did recognition of being a Jew do to his career in France during a period of intense anti-semitism? And during the German occupation in the 1940s, when Adler was herded into a camp at Drancy to be sent to Auschwitz, how did he manage to survive? This is a very difficult aspect of his work to assess, partly because almost all of the Jewish artists of the era still have to be fully investigated. Adler’s Jewishness might also account for his never being elected to the Institut despite the numerous times he was nominated. As one moves further into this book, these questions linger in the mind of the reader, especially since they seem never to have been resolved in the texts.

The next segment, Amélie Lavin’s essay on “Jules Adler ou La Faillite d’un Peintre” (Jules Adler or the Failure of a Painter) tries hard to discuss why Adler fell out of favor in the twentieth century. In effect, the essay notes that his career could be judged a failure by most since he was continuously working in the same mode of naturalist creativity even when modernism was triumphing everywhere. Known as the painter of “the humble,” a recorder of the poor, Adler steadfastly maintained his direction; by comparing his work with other artists such as Constantin Meunier, Lavin does not quite achieve a synthetic response to what Adler did effectively paint. She attempts to show that the artist was trying to do something that was appropriate for the times, but ultimately agrees with others that he was an artist who was continually repeating himself. In this way she confirms that Adler was a local painter, one from the Franche-Comté, rather than a painter of true original merit working in a larger orbit.

Following in this vein Frédéric Thomas’s essay on “Voyage au Pays des Humbles Adler, Le Naturalisme et les Vancus de la Ville Moderne” (Journey to Adler’s Land of the Humble, Naturalism and the Vanquished of the Modern City) situates Adler’s work among other artists whose work focused on those who were beaten down in their lives. He introduces artists such as Maximilien Luce (1858–1941), Jean Francois Raffaelli (1850–1924), and especially Théophile Steinlen (1859–1923) whose own work echoes Adler’s regard for the poor and the disenfranchised, those who were really lost souls. As his career progressed Adler was seen by others, especially critics, as the “peintre des humbles” (painter of the humble people), a quality that was noted by Lucien Barbette in the first biography on the artist in 1938 (63). The phrase became common usage for describing Adler’s work. In drawings, many of which are reproduced in the catalogue, and in large scale oil paintings, Adler found his subjects in wanderers in the city streets, conveying a sense of compassionate despair by using colors that reflected the same sense of hopelessness as did his thematic actors. But by 1911 Adler’s interest was modified as brighter tones entered his work in such paintings as Le Philosophe (The Philosopher) (1910) or Gavroche (Parisian Urchin) (1911), paintings that were more uplifting than his earlier canvases. This essay shows the subtle change in Adler’s approach so that even when obsessed by the downtrodden, he conveyed a sense of hope instead of the bitter misery of his earlier work.

With “Le Peuple Multiple, le Peuple Unique: Jules Adler et Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, Illustrateurs de Leur Temps (1893–1923)” (Many People, Singular People: Jules Adler and Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, Illustrators of their Time, 1893–1923), Laurent Bihl confronts the ways in which these very close colleagues and friends saw their society. As a confirmed activist, Steinlen continually commented on the working conditions of the poor, producing numerous illustrations that were found in the socialist press such as “Le Chambard socialiste” (The Socialist Clamor), a commentary on workers’ conditions that also activated Adler as his painting of La Grève au Creusot (The Strike at Creusot) (1899) makes amply apparent. With a full page spread in the catalogue, this painting triumphantly conveys the fervor of the workers’ movement and their commitment to a strike to improve working conditions. Importantly, Steinlen and Adler are united in this brief essay which heightens the realism of their work while also conveying their use of potent symbolic imagery.

Inspired by events that affected the workers everywhere, Adler’s addiction to a just cause is commented on in “La Manifestation Ferrer (1911)” (The Ferrer Protest [1911]) the next article in the book. Here Vincent Chambarlhac uses Adler’s painting of the Manifestation Ferrer to draw attention to the execution of Francisco Ferrer in Barcelona. This anarchist was summarily killed, provoking worldwide outrage including a Parisian march where many leading political activists expressed their anger. Adler’s large painting of 1911 showed many of the older activists in the front of the event, a moment that provoked the so-called forces of order to react violently against the protest. This painting moves Adler’s work in a different direction as he becomes a painter of contemporary history. It also further documents his commitment to the cause of the workers, adding further depth to what he was doing.

Philippe Kaenel’s essay “La Société en Marche: Iconologie du Mouvement Social Autour de Jules Adler et Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen” (Society in Action: Iconology of the Social Movement Surrounding Jules Adler and Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen), the author effectively studies the way in which these two artists bonded. Both saw the street as the symbolic icon of their work and their era. It was here that both found the people, making the masses central to their creative output. Steinlen saw the street as symbolically stressing the movement of life; Adler maintained this direction showing that street life was complex, complicated (98). Adler set out to show diverse forms of energy, increasing the range of the themes he depicted; the same interest was found in Steinlen, especially his gigantic lithograph of La Rue (1896) where all types of urban dwellers occupy the central stage. As was the case with other images by Adler, his 1908 Chemineau (Vagrant) moves out into the countryside, ostensibly to find a better life. The main contribution of this excellent, interpretive article is to center attention on the urban scene, to suggest that the movement of the people was part of both a personal and iconographic strain that allowed Steinlen and Adler to symbolically reveal that their works reflected a profound procession of life.

“Adler, Regionaliste Malgré Lui?” (Adler, A Regionalist in Spite of Himself) by Catherine Meneux places considerable attention on a number of paintings that Adler did in regional areas, including the Franche-Comté. In each case Meneux points out that Adler continued to focus on the social context of the life of the people. Some paintings, even those of Paris activities such as Joies Populaires (Popular Pleasures) (1898), were immense compositions designed to attract considerable attention at public exhibitions. Others stressed the lives of the wives of fishermen out at sea, as in his Gros temps au large, matelotes d’Etaples (Bad Weather Coming, Fishermen’s Wives at Etaples) (1913). This painting reflects the worries of families similar to a remarkable drawing by Charles Milcendeau from the late 1890s (now in a private collection in the United States) where he reflected on his awareness of the fisherfolk in Brittany. Etaples was an artist’s colony, suggesting that Adler had companions when he did his large canvas now in the Petit Palais, Paris (123). In all of these compositions—large or small—Adler found praise and critical interest suggesting that while he was best known for urban scenes, images reflecting life in differing regions of France allowed him to be seen as a regionalist in spite of himself.

Bertrand Tillier’s essay, “Peindre la Question Sociale” (To Paint the Social Issue), returns to one of the central themes in Adler’s work—the importance of social issues affecting the worker. The author remarks that Adler heroized the worker, allowing him to create huge naturalistic compositions of men at the forge inside industrial buildings working with new machinery. Careful to point out that there were other artists, such as Jean-André Rixens who did similar themes at the time helps to contextualize Adler. Tillier stresses that the Third Republic celebrated worker activity; this was one reason why Adler worked in this vein. When he moved away from figural scenes to focus on landscapes, he showed an awareness of the pollution caused by industry in the often dark and murky environments of his landscapes. This essay is key for Adler’s imagery as it brings to the forefront how he saw the position of the worker in the Third Republic.

One of the most valuable essays is Vincent Chambarlhac’s “Jules Adler, Peintre dans la Grande Guerre” (Jules Adler, Painter of the Great War) since it clarifies Adler’s approach to painting war. He was not at all interested in violence or combat, remaining an artist who stressed the impact of the war on its victims, the soldiers who struggled to exist. He was not so much a reporter of battles as he was concerned about showing effects of the war, even when he completed two gigantic paintings of the Mobilization and the Armistice, paintings that are well reproduced in the catalogue. Sympathetic to German soldiers who were captured, Adler did numerous studies of them; he also helped run a canteen for servicemen so that they could obtain a meal at very low prices. He remained an artist engrossed in the internal lives of soldiers rather than someone interested in war strategies or battles won. His humanitarian values were once again in evidence during this exceptionally difficult period in history. And it is these qualities that the author effectively conveys in this succinct essay.

The next article by Benedicte Gaulard, “Du Peintre au Musée: Jules Adler et Luxeuil” (From the Painter to the Museum: Jules Adler and Luxeuil), ably discusses the formation and opening of Adler’s museum in his birthplace—Luxeuil in the Franche-Comté region. Always maintaining affectionate memories of this small city, Adler donated a number of works to the newly formed museum. When it opened in August 1933, the artist was present at the celebration amidst many of his close friends and supporters. Following the tradition of a few other painters who had separate museums organized for their work (Léon Bonnat and Jean-Jacques Henner among others), the aim of the institution was to keep Adler’s work alive by caring for it in a secure location where visitors could gain a good idea of who he was and what he had actually created. It is significant that this essay is included in this catalogue as it provides a historical footnote to Adler’s career by making a number of his works visible to many who might actually journey to Luxeuil.

The final essay, “Une Oeuvre Trop Méconnue de Jules Adler: Les Toiles Décoratives de L’Etablissement Thermal de Luxeuil (1938–1940)” (A Little Known Work by Jules Adler: The Decorative Murals for the Thermal Baths of Luxeuil [1938–1940]) by Jean Louis Langronet, described Jules Adler’s commission to do six canvases for the new space of the thermal baths at Luxeuil. Reproducing documentary photographs of the original installation, the author shows how some of the paintings were installed. The essay also reveals that Adler ran into immediate difficulties in obtaining the promised funds for his work. As years moved along some of the works were removed and destroyed because this type of decorative painting had fallen out of favor. In the works at Luxeuil, Adler tried something new: he wanted to evoke the mural painting style of Puvis de Chavannes in a modern guise. But in the final analysis, the murals at Luxeuil reiterate the history of all the work of Jules Adler: his approach toward art represented qualities that were no longer valued, supporting the belief that he was not an artist destined to be remembered.

With excellent supporting material at the end of the catalogue, and a substantial number of works reproduced, this publication goes far in trying to present and resuscitate the work of Jules Adler. As the first modern publication to do this, all the authors and organizers must be applauded for their first-rate work. This is not to say that some of the essays are a bit vague, needing further documentation, although on the whole this is a superb publication that discusses a series of significant issues that can be carried further in future publications. It is hoped that the book will be recognized for what it is: a magnificent new step in presenting the career and work of this naturalist artist to younger generations in the twenty-first century.

Gabriel P. Weisberg

Professor Emeritus

University of Minnesota

vooni1942[at]aol.com