The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

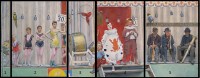

More than twenty feet wide and made up of five panels of oil on canvas, Grimaces et misère—Les Saltimbanques (Grimaces and Misery—The Entertainers) by Fernand Pelez (1848–1913) is a monumental work (fig. 1).[1] It was first exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1888 and in 1889 won a silver medal at the Universal Exposition held in Paris. The work met with critical success—testified to by a double-page reproduction in L’Illustration.[2] Grimaces depicts a sideshow, a device designed to entice viewers to the main circus event, then a common sight in the boulevards of Paris. In subsequent literature on the work and in the exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in spring 2017,[3] Pelez’s Grimaces has been positioned in relation to a curious double: Georges Seurat’s Parade de cirque (Circus Sideshow; fig. 2), a small depiction of the sideshow used to advertise the Cirque Corvi. Both Grimaces and Parade were executed and exhibited in 1888 within months of each other—and indeed within a mile of each other, as Seurat and Pelez both had studios on the boulevard de Clichy at numbers 128 and 62, respectively. Despite this, there is no evidence that the two artists knew each other.

While Seurat’s Parade was barely noted at the Salon des Indépendants in 1888, it has since superseded Pelez’s Grimaces. This is in part because Grimaces all but disappeared in 1913 after it was shown that year at Pelez’s studio exhibition following his death, under the title Grimaces et misère ou les saltimbanques (n°12) (Grimaces and Misery or the Entertainers [no. 12]).[4] It was consigned to hang in the psychiatric hospital Maison-Blanche in Neuilly-sur-Marne in the 1930s and remained in storage until it re-emerged in the 1970s at the Bibliothèque Trocadéro in Paris. Discovering it there, Robert Rosenblum described it as “a virtual double, but in an academic realist vocabulary, of Seurat’s circus theme.”[5] Thus, Grimaces has become the “norm” from which Parade deviates: in the conversation between the two works, Pelez’s naturalism gives way to Seurat’s avant-gardism. And yet I want to argue that, while Seurat’s Parade can be said to make sense aesthetically, it is Pelez’s Grimaces that remains incoherent and enigmatic, bound up with questions about modernity, alienation, freedom, and the individual.

The immediate difficulty of Grimaces is the apparent inconsistency across the five panels that make up the work (fig. 3). As in Parade, Grimaces represents a shallow space occupied by a line of performers and musicians, with a central, more prominent figure. However, Parade coheres within its painted space due to the tight palette associated with the optics of Seurat’s neo-impressionism and the consistency of the taches (strokes) themselves, which both atomize and unite the surface. In contrast, the construction of Grimaces is disjointed in such a way as to resist a single unified view. At the edge of the second panel, there is a break in the striped cloth that defines the shallow stage. It gives way to a red backdrop and a partial figure, in red and green, standing behind the stage, as if waiting to enter. The figure in yellow leaning against the post that marks the resumption of the striped cloth on panel three also indicates that we are seeing through to a different space. But the stage planking of the third panel is more vaguely represented than in the other panels, and it unclear as to why we cannot see the entirety of the drums—it is possible that one extends behind the seated dwarf who is painted across the divide between the third and fourth panels, but it is inconclusive.

More dramatic is the arm that emerges to draw back the red cloth above the head of the dwarf. In angle, attire, and in relation to the scaffolding that suspends a gong still further up, the arm belongs to the behind-the-scenes figure of the second panel. The dwarf, the painted motif on the front of the staging, and the suspended cymbal all provide enough continuity across the panels to discount any suspicion that the third panel might be in the wrong place (as do the preparatory versions of the final work). But the displaced—or so it initially seems—arm is disturbing. The only way in which this rupture makes sense is if the viewer stands at a distance from the painting, roughly according to where we might imagine an original spectator of the sideshow to have stood, and then walks past the painting from left to right. Under these conditions, a scene unfolds for the viewer: we pass each figure, glimpse the figure behind the stage, and then look back upon that figure as it stands just behind the white clown, arm raised, and as if both behind and to the right of the drums. The space then resolves and more figures follow, the last of which is cut off by the edge of the final panel, leaving us with a sense of an abbreviated experience.

Such a reading suggests that the painting mimics the boulevard conditions of the sideshow and positions the viewer as a passerby. That this passing by was intentional is further indicated by a number of the feet, notably the right feet of the two central figures, which appear to follow the viewer around. This effect is achieved by the absence of any indication of a heel, which leaves these feet ungrounded and free of a specific perspectival angle. Similarly, the indications of the planking of the stage under the musicians feet are clear at either end of the work to concur with the viewers’ starting and finishing viewpoints, but are vague in the center and actually collide at the end of the second panel at what we might describe as the crucial point of rotation.

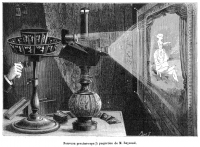

The way in which the disposition of Grimaces configures the act of viewing subtly subverted the space of the Salon, since the Salon spectator was forced into equation with the casual observer of commercial urban spectacles (fig. 4). (At the 1888 Salon, Grimaces was hung at the right height to enable the experience described above.) This is very different from Pelez’s previous works, which had a strong sense of theatricality in their composition, but were akin to the theatrical tableaux instead of this kind of immediate experience. The absence of an audience within the painting exacerbates this—in Seurat’s Parade the silhouetted heads are both a formal motif and another way in which the work presents itself as an aesthetic totality, representing spectacle and spectatorship, and which is set at a distance from the viewer. Pelez’s work confronts the viewer in a manner that is closer to the confrontation of Manet’s Olympia or Bar at the Folies-Bergère, in which the viewer is precariously conflated with the consumer. In resisting being seen all at once, Grimaces engages with the mobile modern spectator of Baudelaire’s or Georg Simmel’s city, and with relatively new and technological forms of spectacle and representation, such as the diorama or the sequential viewing of the praxinoscope (fig. 5).[6]

Something different, then, is at work in Grimaces. Pelez’s project for the previous decade had been the depiction of grim scenes of contemporary poverty—a project that led Émile Zola to label him a naturalist and Joséphin Péladan to describe him as “the painter of pity.”[7] Naturalism had emerged as a literary and artistic movement in France in the 1860s and was concerned with the accurate representation of social reality, and by the mid-1880s it was the dominant aesthetic at the annual Salon. As Richard Thomson has argued, the emphasis on registering everyday events in works of art that could be readily understood suited the egalitarian ideals of the Third Republic.[8] However, Pelez was also accused of exploiting the poor for his own success and of bringing his early work as a history painter (influenced by his time as the student of two academicians in Paris, Félix-Joseph Barrias and Alexandre Cabanel) to aggrandize his subjects.[9] But if works such as Sans asile (Without Hope, 1883; fig. 6) or Un Martyr—Le Marchand de violettes (A Martyr—The Violet Merchant, 1885; fig. 7) can be seen as elevating their grim imagery to high art, Grimaces is on an ambivalent and alternatively critical trajectory.

In Sans asile, the composition has Romantic resonances and revolves around the mother-and-child motif.[10] The slightly muted tones render the scene sympathetic despite the destitution. Grimaces, however, is lit in a harsh daylight, in which the ill-fitting costumes, the bored expressions, and blandness of the stage are pronounced. Bringing the sideshow as a subject inside the Salon was an interesting move in itself; the nature of the sideshow being that it was outside the main show, as an advertisement for what was inside. Its status as a commercial seduction, combined with the composition of Pelez’s representation, might be read as an indictment of the Salon—and by association of naturalism—as fundamentally superficial. But Grimaces is operating in several modes, one of which is allegorical, and which is also emphasized by the construction of the viewing as passing by. From left to right, the figures increase in age, from the small limp figure of a child, to an older child and two adolescents, to the group of three middle-aged figures in the center, and finally to three aged musicians, equally limp and decrepit. As Isabelle Collet has noted, this progression is reminiscent of the allegory of the ages of man, or the degrés des âges.[11] The social critique is bleak: the prime of life is represented by three types—the figures of the dwarf, the clown, and the owner or circus master—in other words, the deformed spectacle, the outcast whose mask smiles, and the man who makes money out of this dismal array. This critique relies on the recognition of these types, and clearly they were familiar to contemporary viewers. In l’Echo de Paris, the critic Alexandre Georget wrote of Grimaces: “It’s the parade: the subjects spread in front of the stall, from the little albino encountered in other canvases of M. Pelez up to Mossieu Bilboquet.”[12] Bilboquet was a theatrical character—the wily leader of a troupe in the early nineteenth-century comedy Les Saltimbanques (The Entertainers). In Les Saltimbanques from 1839, Honoré Daumier recast Bilboquet as a minor administrator, profiting from urbanization and social change.[13]

Each figure in Grimaces is isolated, and even where there is close proximity—the dwarf in front of the clown or two of the musicians—there is no contact. The alienation represented by these isolated figures is enhanced formally by the vertical stripes behind them, which effectively destroy any unity suggested by the overall horizontal emphasis of the composition. The resigned expressions and lack of vitality in all the figures—except the clown and perhaps Bilboquet, who stands with a confident sense of his own presence and an appearance of agency amid automatons—implies that the individuals are as trapped as the chained monkey and the parrots with clipped wings that sit in metal loops above them. The force that traps them is clear enough—money dominates the scene, the zeros of the signs formally echo the metal loops and the open mouth of the clown who appears, somewhat sinisterly, to be in concert with them.

The representation of the sideshow as an industry opposes earlier conceptions of the circus as a space outside society, or Daumier’s equation of the traveling troupe with both the wandering minstrel and the vagabond outcast of urbanization.[14] It also opposes the image of the clown, as it would be taken up across the French avant-garde in the next half century, as a vision of heroic individualism, free of bourgeois society through the refusal to conform, and the outcast as a victim of indifference.[15] In Grimaces, however, the social outcast becomes the exploited worker: individuals are absorbed as the mechanism of organized leisure with no more freedom than a marionette.[16]

Arguably, Seurat’s Parade preserves something of the mythic space of the circus, and the central figure, albeit isolated, is an ambiguous priest-like magician who recalls the clown or saltimbanque as a symbol of the artist himself, standing at a remove from his audiences. Paul Smith argues that the immateriality of the musicians in Parade, their geometrical perfection, and the sense that they are almost dissolved by light speaks to the work as an allegory of the religious importance of music. Smith also suggests that the work conforms to a Wagnerian understanding of art as an expression of the supreme unity at the heart of things—its message, Smith writes, following Arthur Schopenhauer, is one of salvation through art and aesthetic experience.[17] Against this, however, Jonathan Crary persuasively reads the suggestion of a magician in the central figure as emblematic of a modernized order of spectacle, “of the mass management of attentiveness and its commodification.”[18] In Crary’s reading, the work is unified not by a transcendent impulse but by a nihilistic force that announces a vacancy and absence that he argues suffuse the entire painting.[19] This nihilism arises from the sign indicating the price of admission, and the fact that this price tag occupies a space formerly aligned with the vanishing point—it becomes, writes Crary, one of the vanishing points of modernity, recalling Karl Marx’s discussion of “price” as “the symbol of itself . . . the materially present representative of the price, thus of itself, and as such, of the exchange value of commodities.”[20] For Crary, the ambivalence of the price tag speaks to the symbolism of the whole painting. Seurat, he writes, “situates his own practice within a regime of signs that are symbols of value rather than possessed of any intrinsic value themselves. It is within this problematic that his work is crucial to any consideration of the question of ‘symbolism’ in late nineteenth-century culture.”[21]

In this reading, Parade draws closer to the isolated figures and emphatic zeros of Grimaces, which is an image of the kind of disunity and alienation under capital described by Marx. For Marx, particularly in his early writings, the notion of “productive activity” was crucial to what it means to be human.[22] In The German Ideology (1845), Marx wrote that “The way in which men produce their means of subsistence . . . is a definite form of activity of these individuals, a definite form of expressing their life, a definite mode of life on their part. As individuals express their life, so they are. What they are, therefore, coincides with their production.”[23] Key to this activity is that both the human subject and the raw materials of her production are altered in their exchange: the human subject is both a part of the world and brings the world under her control or domination. Furthermore, this activity is “not a determination with which [the subject] is completely identified,” which is to say that the subject understands herself apart from her activity and makes that activity an object of her will and consciousness. Under these conditions, the activity—and the subject—can be understood as free.[24] Under capitalism, this productive activity is distorted to the extent that instead of it being a mode of life that defines the individual subject, it estranges the subject from herself and from society. Activity shifts from an end to a means—a shift that signifies a loss of freedom and agency as the activity falls under the system of commodity production. In their ill-fitting costumes, with their distracted gazes and lack of energy, the figures of Grimaces no longer embody their roles but indicate the separation between the role and the individual whose subsistence relies on his or her performance of their part.[25] Their activity is no longer conscious and willful, but a necessary means of existence. The harsh daylight of the painting exacerbates this—the clown is nothing other than a worker in a costume with makeup applied to his face.

Importantly, productive activity is fundamentally social for Marx, whereas the consequence of alienated activity is alienation from other people. Instead, a new hierarchy emerges that is engendered by this alienated labor—“the domination of the non-producer over production and its product”—which, in Grimaces, is the figure of Bilboquet. Bilboquet’s proprietorial stance has already been noted, and in Marx’s terms he represents the capitalist who stands in opposition to the worker but is also bound up with him, as each is reliant upon the other as means to achieving their mutual ends. Bilboquet’s proximity to the price sign emphasizes this relationship. The isolation of the workers in Grimaces also speaks to the alienation between people of the same class, and the chained animals indicate the loss of a distinction between the human and the animal that follows the loss of freedom of activity. However, where for Marx historical progress and the determination of human action by history are (albeit controversially) oriented toward the increasing liberation of human action, the effect of the “ages of man” motif in Grimaces is the kind of nihilistic vacancy and absence found in Crary’s reading of Parade.

Grimaces, then, depicts a state of worldlessness: the troupe of players, which formerly existed as a group on the edge of society, is drawn into a social structure that simultaneously dispossesses the players of their small community and of the modern world at large.[26] The latter occurs because of necessity, that is to say, because the demands of subsistence deny the individual any opportunity to engage freely with the world. This worldlessness is underlined in Grimaces by the sideshow trope, in which the individuals are subject to worlds they do not appear in and certainly have no agency within.

At the same time, in the intensity of Pelez’s realist depiction of the faces of the figures and their detached expressions (Bilboquet aside)—expressions that refuse the kind of empathetic reception that Pelez’s former works often invited—Grimaces addresses another aspect of the modern world: the increasing preoccupation with the private self. The sense that the faces of the players mask interior private worlds—more hidden content in the painting—contributes to the dissociation of the individual figure and his or her activity. However, it is also the site of resistance. Unlike Parade, in which there is unity, in Grimaces the psychological interiority that is shut off by the players as they take up their roles is a source of further fragmentation and isolation, but also of conflict. In this, Grimaces breaks with the naturalism of the Salon and is aligned with the realism of writers such as Stendhal, Balzac, Flaubert, George Eliot, or Dostoyevsky, in whose work, as Arnold Hauser notes, “the soul and character of man are seen as the opposite pole to the world of physical reality, and psychology as the conflict between subject and object, the self and the non-self, the human spirit and the external world.”[27] The suggestion of the private self opposes the alienated system in which the figures of Grimaces are working, although there is no sense that this interiority offers any form of escape or freedom other than inward (also something shared with the subjects of works by novelists such as Eliot or Flaubert, and later, Hardy).

These divisive conflicts and fragmentations are echoed in the formal conflicts and fragmentations of Grimaces. Part of what refuses to settle has to do with the execution. In 1888, the critic Henry Houssaye sensed something of this when he wrote of Grimaces: “If this immense tableau attracts attention by its strange subject and vast proportions, it retains that attention by its qualities of execution and the deep sadness evinced by it.”[28] We can assume that Houssaye had the disjunctions of the scene in mind, but there are other strangenesses in the execution of Grimaces. It is relatively thinly painted in oil, which is not unusual for Pelez, but what differs markedly from previous works are the areas of almost complete unfinish, such as the shoes of the middle girl and of the last musician, and places where the lack of cohesion or continuity across panels results in an emphasis upon the painted surface itself. The painted banner above the heads of the clown and the musicians is an example of this. It appears to be a banner, but the flatness of its ground, the abrupt finish at the edge of the fourth panel, and the striking repetitive motif render it as much a decorative element on the surface of the painting as a represented object. It also draws attention to the garish red frog on the clown’s white costume and to the flat green front of the stage that replicates the shape of the patterned banner and effectively frames the staged space between these horizontal areas of color. This emphasis on the decorative, as well as the unfinished style of the painting, consolidates the subject of spectacle, but also disrupts the “reality” of the scene. The unfinished shoes are sketched in paint, the line almost caricatural in places. The musician’s shoes are more like the sketched shoes of a number of van Gogh’s peasants than those in Pelez’s previous works. In these moments, Grimaces pictures its own evolution—of realism into representation, of sketch into painting, and of spectacle into art. It even hints at the transformation of Grimaces into its own caricature—something that had happened to a number of Pelez’s works and even to Pelez himself (fig. 8).

As a painting, then, Grimaces provokes further questions in dialogue with the themes raised by the content. The painting and the painter are unable to resolve the complexities of the situation they attempt to depict. What is set up by this irresolution are dualities between the natural and the artificial, and in the accentuated construction of the painting it is the artificial not the natural that dominates. Again, there is a deviation from Salon naturalism and the kind of coherent scenes of social reality by painters such as Alfred Roll, Émile Friant, or Léon Lhermitte, or indeed earlier Pelez. However, the way in which the viewer is manipulated by the painting can be read either as in accord with naturalism’s deliberate replication of the physical experience of the everyday, or as a subversion of naturalism, as Grimaces indicates that it is a work about visual culture. I am inclined to see it as a painting that plays these two readings against each other: in this, Grimaces is a highly mediated work that hints at the potential emptiness of representation in its unfinished state and in the diffusion of the subject matter as spectacle in multiple media transformations, each sold on to the next, so to speak. Grimaces, then, is also a motivated work that draws out pictorial, moral, and political significances, and that anticipates, in its contradictions, writer and philosopher Paul Desjardin’s short attack on naturalism the following year. Desjardin complained that what had befallen France was “a simultaneous invasion of positivism in thought, of naturalism in art, of mechanism and analysis in criticism, of realism and the hoax in literature, of agnosticism and indifference in religion, of practical sense in life.”[29]

Again, the act of bringing the sideshow into the Salon becomes important. Outside of the Salon, the sideshow was instrumental, an act designed to entice viewers to something else, it is, to borrow Heidegger’s category, absorbed in its own use value. As a work of art, though, ripped from the system in which it has a use, the painting of the sideshow sets up only its own world—it “entails a superior refusal of what is commonly present-at-hand.”[30]

For Heidegger, the work of art itself opens relationships, and in Pelez’s construction the sideshow forcibly “creates the space that it pervades.”[31] The world of the sideshow, in all its pity and grim reality of ill-fitting tights and commercial prospect, is set forth in the isolation of its new non-instrumental context, from which it forces itself anew upon the viewer. Somewhat ironically, the worldlessness of Grimaces “worlds” forth. Pelez’s achievement with Grimaces is not art as salvation, then, but the creation of a work of art that neither transcends nor settles and that remains a strange and disturbing encounter.

Grimaces is, in several ways, a painting in disguise. Immediately, it looks like naturalism, but it does not operate in accordance with positivist, naturalist ideologies.[32] Naturalism gives way to other modes of expression: toward a strange kind of symbolism, toward the decorative, and toward an engagement with contemporary forms of moving visual spectacle. The dominance of naturalism at the 1888 Salon seems to have clouded what was strange about this work, however, and much of the criticism of that year was a strident defense of naturalism against contemporary symbolism. Eugene Montrosier wrote of Grimaces that “Monsieur Pelez has told us this painful story with a paintbrush that burns like a verse from Dante. He has already torn the robe from misery; this time, he has ripped it off completely to show us the monster in its hideous grandeur.”[33] Montrosier’s imagery of the unclothing of truth seems particularly poised against Jean Moréas’s “Symbolist Manifesto” of 1886, published in Le Figaro, in which Moréas wrote that symbolism “clothed the ideal in perceptible form.”[34] Montrosier goes on to detail the pity of the scene in Grimaces, but quickly becomes sentimental—something that is not supported by the painting itself. For example, he suggests that the children in the sideshow are a family and that the tallest of the figures on the left is the mother. Such a reading is certainly aligned with the sentimentalism of Sans asile, in which the vestiges of familial structures offer some kind of comfort, and, as John Hutton notes, render the image “nonthreatening, immobile, helpless . . . designed to reassure rather than to alarm.”[35]

Grimaces is a deeply pessimistic work, both about fin-de-siècle society and about the relation of art to that world. The dismantling at work in Grimaces is itself an image of decay, even as it turns toward formal qualities that would shortly be celebrated by the avant-garde for their “truth.” If the “truth” of painting appears in Pelez’s picture, it is bound up with questions of what it means to tell the truth. Two later works speak to this aspect of Pelez’s late project: the unexhibited La Vachalcade (To Live in Poverty; ca. 1896–1900; fig. 9) and his last exhibited work, L’Humanité ou le Christ dans le square (Humanity or Christ in the Square, 1896; fig. 10). The former is a disturbing image of a group of children in masks and oversized clothes participating in a carnival held in Montmartre.[36] Drawing is again evident across the thinly painted work, which shows the subversive freedom of the carnivalesque to be a monstrous illusion. The latter, L’Humanité, perhaps elicited some of the criticism that Grimaces escaped. L’Humanité is also painted across several panels and depicts a line of figures, this time drawn from the bourgeois and lower classes, arrayed in a park setting and all facing the viewer. Many of the figures have the same disparate isolation as Grimaces, and even those in groups are lacking in interaction. The most dramatic development since the complicated realism of Grimaces is the inclusion of a large crucifix suspended above the park and the line of figures, oblivious to the cross, indeed with their backs turned toward it. The painting is a deeply cynical view of a decadent society; its pessimism is condemnatory to the point of nihilism. Gustave Geffroy wrote at length about L’Humanité in his criticism of the 1896 Salon. Although he seemed to like the way Pelez painted, Geffroy was appalled by the subject matter. He cited Pelez as an example of a generation of artists who believed that it was possible to revolutionize painting simply by choosing a new subject that would attract attention.[37] This resembles the accusations of insincerity leveled contemporaneously at symbolism, and much of Geffroy’s criticism of Pelez makes sense as a defense of naturalism against a painter who Geffroy suspected was moving toward symbolism. He accuses Pelez of confusion, calling the painting “somewhere between a representation of vaudeville, a desire to make a fierce self-assertion and supernatural evocation.”[38] Geffroy objects to the lack of unity in the work, and he was not alone—L’Humanité was shown at the 1896 Salon and was widely disliked. After this reception, Pelez retreated completely from the art world, never publicly showing or selling his work again.

And yet, this criticism, this inability to label Pelez or to wholly understand what he was doing is the overlooked achievement of Grimaces. Grimaces is a work that at once brings the pageant of the sideshow into the Salon and, in performing this experience, elicits something close to a Freudian understanding of the “unheimlich,” which is the disturbing encounter with the familiar rendered strange and disruptive. Pelez’s Grimaces, in its refusal to settle—as arguably Seurat’s Parade settles within its own aesthetic—remains enigmatically poised between aesthetic and critical orders, and a complex vision of the worldlessness and alienation of nineteenth-century society. It heralds in subtle ways the experiments of the early twentieth century with construction and visual experience, combined with an acute anxiety about painting and social criticism.

The author would like to thank Ségolène Le Men for her positive review of this paper, and her thoughtful suggestions toward its improvement. Thanks also to Petra Chu and Cara Jordan for their comments on the text.

[1] The painting has appeared under variations of this title, I am using the version used by the Petit Palais where the work is held.

[2] L’Illustration 2379, 1888, np.

[3] Seurat’s Circus Sideshow, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, February 17—May 29, 2017.

[4] On this exhibition, see Ségolène Le Men, “Le naturalisme de la misère ou la vie en gris,” in Fernand Pelez: La Parade des humbles, exh. cat., ed. Isabelle Collet (Paris: Paris-Musées, 2009), 28–33. This catalogue accompanied the exhibition at the Musée du Petit Palais, September 24, 2009–January 17, 2010.

[5] Robert Rosenblum, “Fernand Pelez, or the Other Side of the Post-Impressionist Coin,” in Art, the Ape of Nature: Studies in Honor of H. W. Janson, eds. M. Barasch and L. Freeman Sandler (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1981), 707–18.

[6] Jonathan Crary, Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001), 260.

[7] Émile Zola, Le Voltaire, June 18–22, 1880, n.p. On naturalism in France, see Gabriel Weisberg, Beyond Impressionism: The Naturalist Impulse in European Art 1860–1905 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1992), 54. “Le peintre de pitié,” Joséphin Péladan, “Fernand Pelez (1843–1913),” La Nouvelle Revue 34 (1913): 457–62.

[8] Richard Thomson, Art of the Actual: Naturalism and Style in Early Third Republic France, 1880–1900 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

[9] On the cliché of the deserving poor and the reassurance of “sentimental realism,” see John Hutton, “Les Prolos Vagabondent: Neo-Impressionism, and the Anarchist Image of the Trimardeur,” Art Bulletin 72, no. 2 (1990): 296–309. In 1888, Eugène Montrosier wrote that “artists love to paint misery elevated to the rank of history painting.” E. Montrosier, Salon de 1888: La Peinture (Paris: L. Baschet, 1888), 29.

[10] On the comparison between Pelez and William Bouguereau, Paul Delaroche, Jean-Claude Bonneford, and others, see Collet, Fernand Pelez: La Parade des humbles, 62.

[11] Ibid., 91n9.

[12] Alexandre Georget, “Notes sur l’art,” L’Echo de Paris, 1888. Italics in original.

[13] For example, in the lithograph The Mountebanks, for which the accompanying text reads “Oh Maître Bilboquet, we have had it . . . these clowns will steal our show! Don’t worry, Gringaillet, they’re no competition, they are just comedians!”

[14] Hutton, “Les Prolos Vagabondent,” 299n7.

[15] See Jean Starobinski, Portrait de l’artiste en saltimbanque (Geneva: Albert Skira, Les Sentiers de la création, 1970).

[16] Rosenblum describes the figures in Grimaces as “lined up as if in a shooting gallery,” a description that aligns the sideshow with the fairground stall called the “Jeu de massacre,” a game in which the spectator throws balls at puppets dressed to represent types.

[17] Paul Smith, Seurat and the Avant-Garde (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 124.

[18] Crary, Suspensions of Perception, 201.

[19] Ibid., 198.

[20] Crary, Suspensions of Perception, 198; Karl Marx, Grundrisse, trans. M. Nicolaus (New York: Random House, 1973), 211–12.

[21] Crary, Suspensions of Perception, 198.

[22] Specifically the Marx of Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right (1843); Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844; and The German Ideology (1845).

[23] Karl Marx, German Ideology, trans. T. Delaney and R. Schwartz (London: Progress Publishers, 1968), part 1. Italics in original.

[24] On freedom and alienation in Marx, see J. J. O’Rourke, The Problem of Freedom in Marxist Thought (Boston: Reidel, 1974).

[25] Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, trans. Martin Milligan (New York: Dover Publications, 2007) section 5, 67.

[26] “Worldlessness” is Hannah Arendt’s term in her critique of Marx’s natural or social man, but it also anticipates existentialism’s debates over authenticate existence. I am using it in the sense associated with Arendt’s point about detachment from the world as a condition from modernity and in relation to her discussion of slavery and poverty as conditions that “hide” human beings from the public space (the world) and thus disable their chance to establish unique identities in the world. See Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, 2nd ed., (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958; repr. 2013); Shiraz Dossa, The Public Realm and the Public Self: The Political Theory of Hannah Arendt (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press; repr. 2006).

[27] Arnold Hauser, The Social History of Art: Naturalism, Impressionism, the Film Age (New York: Routledge, 1999), 4:225.

[28] Henry Houssaye, untitled review, Journal des débats politiques et littéraires (Paris), 1888, 2. Translation by the author.

[29] Paul Desjardins, “Sur M. E. Melchior de Vogüé, à propos de sa réception académique,” Revue bleue, xxvi, June 8, 1889, 713–19. Italics in the original. On the criticism of naturalism, see M. Marlais, Conservative Echoes in Fin-de-Siècle Parisian Art Criticism (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992).

[30] Martin Heidegger, “On the Origin of the Work of Art—First Version, 1935,” The Heidegger Reader, ed. Günter Figal, trans. Jerome Veith (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2009), 135.

[31] Heidegger, “On the Origin of the Work of Art,” 135n14.

[32] See Weisberg, Beyond Impressionism, 54n5; Thomson, Art of the Actual.

[33] Montrosier, Salon de 1888, 31n7.

[34] Jean Moreas, “Le Symbolisme,” Le Figaro (Paris), September 18, 1888, supplement, 1–2.

[35] Hutton, “Les Prolos Vagabondent,” 303n7.

[36] The first of these processions took place in March 1896 in mid-Lent. “Vachalcade,” derives from “manger de la vache enragée” (to eat the rabid cow), a phrase used to mean “to live in poverty.” The Montmartre-created “cow-valcade” mocked the traditional cavalcade of the fattened ox. In 1897, Pelez designed a poster and a float for the event. See P. Cate and M. Shaw, The Spirit of Montmartre: Cabarets, Humor, and the Avant-Garde, 1875–1905, exh. cat. (New Brunswick, NJ: Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Museum, 1996).

[37] Gustave Geffroy, “Salons de 1896 et 1897,” La Vie Artistique (Paris: Dentu, 1897), 226–81. Translation by the author.

[38] Geffroy, “Salons de 1896 et 1897,” 278n22.