The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Cézanne Portraits

National Gallery, Washington, DC

March 25, 2018–July 8, 2018

Exhibition catalogue:

John Elderfield, ed., with Mary Morton and Xavier Rey and with contributions by Alex Danchev and Jayne S. Warman,

Cézanne Portraits.

London: National Portrait Gallery Publications, 2017.

255 pp.; 108 color illus.; checklist.

$55.00

ISBN: 0691177864

To start with an admission: each term, I wrestle with how to incorporate Paul Cézanne’s portraits into my undergraduate lesson plans. I’ve read stacks of books and articles that discuss Cézanne in relation to modernity and modernism, Cézanne in relation to the cultural geography and poetics of painting the Provençal landscape, Cézanne in relation to paleontology and plate tectonics, or Cézanne in relation to conceptions of originality. I’ve lectured on all this while deploying his paintings of Mount Saint-Victoire or paintings of apples and oranges ready to tumble from the pictured wooden tables to explain composite perspective and constructed brushstrokes. But compared with the ease with which I reach for a text on his landscapes or still-lifes, Cézanne’s portraiture continues to elude me. His portraits make me uneasy, unsettled, insecure about what to do and say before them. And, apparently, I am not alone. As echoed in the introductions to recent book-length studies as an explanation for their raison d’être, Cézanne’s portraits remain understudied. Pace Susan Sidlauskas, on the opening page to her recent close study of the portraits after Hortense Fiquet Cézanne:

Even if the body of scholarship on Cézanne is among the weightiest in art history, one genre in this painter’s oeuvre has remained relatively unexplored: his portraits. . . . The portraits . . . have not received nearly as much attention as the still lifes, the bathers, and the landscapes.[1]

Citing Cézanne’s supposedly continually ignored portraiture practice, the museum directors of the National Portrait Gallery (London), National Gallery (Washington, DC) and Musée d’Orsay, in a co-authored forward to the catalogue accompanying the current exhibition, explained the current exhibition’s significance:

This is the first exhibition to be devoted exclusively to Cézanne’s portraits, an important, yet often neglected, aspect of his art. As such, it provides an unrivaled opportunity to reveal the extent and depth of his achievement in portraiture, arguably the most personal, and therefore most human, aspect of his work.[2]

(Not quite. Dealer Ambroise Vollard mounted the only other exhibition dedicated to the portraits in 1910). Standing before Cézanne’s depictions of his family, friends, and sympathetic patrons and colleagues—Victor Choquet, Gustave Geffroy, Vollard, or the many series after his mistress-turned-spouse, Fiquet Cézanne, shown at the National Gallery, Washington, DC—I searched the painted surfaces for responses to the types of questions that beset nineteenth-century portraiture practices. Where early nineteenth-century conceptions of portraiture had stressed the idealization and beautification of the portrayed—think Jean-Dominique Ingres and his commissioned portraits of porcelain-skinned beauties—by the century’s end, artists and their art-critical allies like Edmond Duranty had started to rethink the aims and possibilities of this art (fig. 1).[3] More recently, the historical questions raised around portraiture have been extended through feminist, psychoanalytic, and critical biographical approaches à la Tamar Garb, Heather McPherson, Susan Sidlauskas, and, in the Cézanne Portraits catalogue, John Elderfield, Mary Morton, and Xavier Rey.[4] Amongst these questions: at exactly whom or what do I look when I look at modernist portraiture? What are these portraits as artifacts, documents/records, projections, or memories? What do I do with the person made into an object under study by the painter, when the painter has been an object so intensely scrutinized in our own art historical studies? In short, who exactly do I see portrayed in Cézanne’s portraits—a subject, an object, or an objectified subject made into an extension of the artist?

Appreciating how exhibition reviews like this one may act to preserve these displays for posterity, I often seek to strike a professional tone as I write—a tone which diplomatically (I hope) evaluates the successes and shortcomings of these exhibits with an attention to the curatorial intervention via the stories of art narrated on the walls and constructed through the attendant texts in lushly illustrated catalogues. While I seek to maintain that professional tone here, I also wish to take a slightly alternate tack to Cézanne Portraits, which I saw in its London and Washington, DC, iterations. (It also traveled to the Musée d’Orsay.) I wish to claim my own experience before these Cézanne portraits by writing this review from the first person, precisely because portraiture seems so very personal in its portrayal of an individual. Portraiture’s intimacy comes through in its presumed visualization of the relation between the person who paints and the person who has been painted, in the projection of the painter onto and through the portrayed, and, implicitly, in the question of my (the viewer’s) place in all this. Even the most blatantly posed, stylized, and rote portrait—those presenting the beautiful and unblemished, the spectacularly bejeweled and lavishly bedecked, exquisitely outfitted and fashionably coiffed—implies the potential for intimacy and vulnerability. Such portraits signal the possibility that I may search and ultimately find the authentic or real person behind the layers of glossy paint. I may discover visual clues permitting me to read the qualities or characteristics of the person portrayed—class, status, taste, and more—all the while knowing their image to be editorialized and constructed. Yet Cézanne’s portraits document, or have been seen to record, not so much the person portrayed but the artist’s own frustration and failure to make close and lasting connections with those he painted. In turn, his isolation or misanthropy have been interpreted as making it difficult for those outside the picture plane, like me, to connect with either the portraitist or the portrayed. Using select paintings from the National Gallery exhibition, I wish to contemplate the subtleties of the private, the public and the personal in Cézanne’s portraiture—subtleties the National Gallery surely intended attendees to interrogate as they stood face-to-face with these portraits.

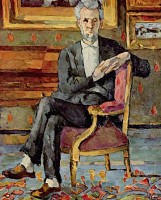

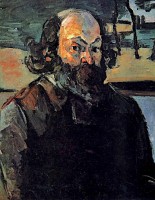

The exhibition chronologically charted the formal development of Cézanne’s portraits, from his brooding self-portraits of the early 1860s painted in his couillarde (ballsy) style, to his late portraits after his domestic servants from the early 1900s composed through faceted planes of color. In tandem with Cézanne’s stylistic development, the exhibition told the tale of his shifting relations with his family and friends. Across his slightly more than four decades of work, only 160 portraits are counted in his corpus spanning more than 1000 completed paintings. Throughout, the National Gallery cast these portraits as experiments in capturing likeness and “vivid human presence.”[5] Certainly, Cézanne’s portraits provide clues for interpreting the extent of his connection with those he portrayed. In some instances, his portraits clearly memorialize, even monumentalize the importance of those portrayed at crucial moments in his life and work. For instance, Cézanne’s life-size portraits of Gustave Geffroy or Ambroise Vollard capture the respective critic and dealer who, in their articles and exhibitions, made Cézanne’s highly private paintings public and thus made his art intelligible and appreciable to late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century art critical and art market circles (fig. 2). As homages to those who promoted him, the large scale at which Geffroy and Vollard were painted corresponded to their significance to Cézanne; and yet, their outsize presence has not been matched by felt psychological or emotional closeness but has served to underscore the distance or, perhaps, deference felt by Cézanne. In other instances, he captured the more intimate presence of the portrayed through small scale works, like the portrait of his kindly patron Victor Choquet who amassed a substantial collection of paintings from early exhibitions of the Société Anonyme des Peintres, Sculpteurs et Graveurs (soon-to-be the Impressionist exhibitions). With his identifiable and handsome shock of grey hair, Choquet strikes a casual and convivial pose (fig. 3). His legs crossed and hands clasped, he turns his elegantly dressed form towards the viewer. From his seat in this comfortable domestic space, Choquet becomes a picture of openness and approachability, especially when compared with the formality of the aforementioned portrait of Geffroy stiffly seated in his studio behind the heavy barrier of his desk.

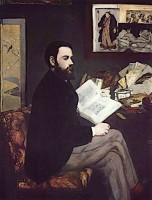

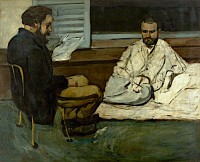

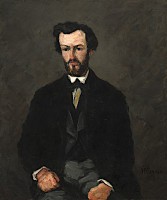

In his catalogue essay, Elderfield has recounted how portraits of art critical and other allies (dealers and patrons) were commonplace by the 1890s. To take but one example: Edouard Manet’s portrait of Emile Zola, an early example of this type of portraiture, the pamphlets have legible titles and the prints and photographs on the wall have legible images, making the art critic’s interests and interventions—some of them on Manet’s stead—clear to all who closely look (fig. 4).[6] Not so with Cézanne who also immersed himself in a circle of littérateurs (writers). As evidenced in prominent examples at the National Gallery, he diverged from Manet in representing hommes de plume (men of letters): words are read aloud, but unheard by me in Paul Alexis Reading a Manuscript to Zola (fig. 5). News headlines are scanned, but unseen by me in The Artist’s Father Reading L’Evenément (fig. 6). Such portraits—both those after literary giants like Geffroy, Alexis, and Zola, or journalist and critic Anthony Valabrègue and those after informed readers like Cézanne père—present the learned and the curious locked within a world of words (fig. 7). Cézanne has underscored this absorption, by having Geffroy or Valabrègue face frontally but then blackening their eyes into thick smudges, or painting Alexis turned inwards and towards the mandarin Zola. In these instances, Cézanne has denied the possibility for those beyond the picture plane to enter the painted realm. From books and newsprint as props to multifigure portraits dedicated to literary personalities, Cézanne’s portraits interestingly insist on seeing the visual in relation to the literary, and, of course, the literary in relation to the visual. But he also introduced a paradox into these portraits. As Cézanne must have realized, some element of the original medium—whether writing or painting—becomes lost in translation due to restrictions of the language inherent to each media. To that end, Elderfield has underlined how the artist, understanding the elision between description and ownership, codified “his very own language, one that would differentiate his strong sensations about the world he occupied from those—less strong, is the implication—experienced by the owners of the practice of painting in Paris.”[7] The title, Cézanne Portraits, and not Cézanne’s Portraits, further underscores Elderfield’s and his fellow curators’ interest in this issue of ownership as it intersects with the portrayal of other people.

Perhaps as an expression of his appreciation for Geffroy, who had published the first full-length article on the artist in 1894 and so worked to wrest him from obscurity and translate his painting into written word, Cézanne painted his portrait (see fig. 2). Completed in 1895, this portrait may be understood as Cézanne responding to Geffroy’s fastidious description of his [Cézanne’s] technical and stylistic concerns as much as Geffroy responded to Cézanne’s painterly practice. But, as aforementioned, Cézanne alludes to the limitations of words and images. Geffroy has been surrounded by tools indexically signaling his art critical trade. An erudite scholar and writer, his desk has been cluttered with a knife used to sharpen his pencil, opened books, small vase with pink buds, and lithe plaster statuette of a female nude. With additional books and loose papers piled high beside him and the spines of still more colorfully bound books behind him, the critic sits in a tightly compressed space. Resting one hand on an opened page, as though he had recently plucked these two tomes from a nearby shelf in response to my (the viewer’s or Cézanne’s) comment or question, Geffroy’s other hand takes the form of fleshy fist mottled in pink, orange, blue, and grey. I imagine Geffroy to be comparing reproductions across these two folios or comparing his notes scribbled in the small notebook against what has been published. Yet any engagement between the portrayed and those outside the picture plane has been occluded. Geoffroy’s gaze, while directed up from the books under study, has not been directed outwards. Instead, his irises and pupils—and this recurrently happens in Cézanne’s portraits—have been blurred, making his expression indecipherable to me. Geffroy’s desk and the open folios atop it become additional obstacles, impeding me from physically or intellectually connecting with him. The texts, while signaling learnedness, do not lead to a shared knowledge. I cannot read what has been written or printed on those pages and spines. The books before Geffroy are blank, unmarked by print or pen—an emptiness which simultaneously impresses upon me the need to read sources beyond the painted plane and my reliance on Cézanne’s reading. In refusing this degree of legibility Cézanne has required me to rely on his interpretation of Geffroy. And, in this, he has cannily alluded to the ways in which critics similarly made their readers dependent on their interpretations of the artist and his work.

Cézanne’s portrait of Vollard may similarly be read as a token of thanks to the dealer for publicizing his art and securing his art historical reputation (fig. 8). Though Vollard legendarily endured 115 sessions for his portrait, he still displays the typical Cézannesque blank stare emptied of subjectivity, though here, his stare may be attributed to physical exhaustion. (The dealer notoriously suffered from narcolepsy.) With a closed book in his one hand—perhaps a stockbook scrawled with records of early sales of Cézannes—Vollard plunges his other hand into his pocket. An émigré from the French-controlled Ile de la Réunion, Vollard opened his first gallery in 1893 in the rue Laffitte, then a prominent corridor for buying and selling modern art. Down the street, Paul Durand-Ruel would coordinate Impressionist retrospectives and exhibitions coincident with the Gustave Caillebotte Bequest (1894–97) that bequeathed dozens of Impressionist paintings to the Musée du Luxembourg: a retrospective for Caillebotte in 1895; a show of Claude Monet’s Rouen Cathedral series, also in 1895; a posthumous exhibit for Berthe Morisot in 1896; and a financially failed retrospective for Alfred Sisley in 1897. Durand-Ruel thus used Impressionism’s anticipated entry into the Musée du Luxembourg to advertise his showroom and capitalize on his stock. So too did Vollard. In November and December 1895, he mounted the first retrospective dedicated to Cézanne.[8] His unflagging promotion of Cézanne continued into the twentieth century: in 1910, he mounted an exhibition of his portraits, and he published biographies of the artist in English, German, and of course, French.[9] By 1899, when Cézanne painted Vollard’s portrait, his paintings had started to sell for a substantial profit—in large part due to the dealer’s international network extending to Central and Eastern Europe.[10]

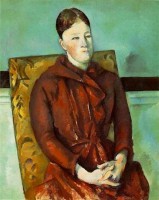

Other than these and a few additional portraits after Cézanne’s more professional circles, the National Gallery exhibition turned to his portrait practice as it came to be directed inwards to concentrate on his family, friends, peasants, domestic servants, and paid models. Compared with the signs of scholarship in Gustave Geffroy or signs of the studio space in Ambroise Vollard encoded with at least some sense of a specific place, these latter portraits offer few contextual cues to decode the personality or presence of those portrayed. These portraits appeared incredibly private but awkwardly impersonal. Wallpapers, flowered panels, painted screens, and hung paintings (some by Cézanne or by his friends and colleagues hung behind his sitters) feature as backdrop. Stiffly upright or overstuffed chaises furnish bland bourgeois interiors. Such details can only loosely be ascribed to the taste or status of the person presented. Even in the instance of Fiquet Cézanne, his mistress starting in 1868 and then wife starting in 1872, Cézanne rarely included the type of material details that could be meaningfully ascribed to her personality, her relationship with her husband-artist or her life outside the role of muse and model. From the start of their liaison until Cézanne’s death in 1906, the artist and Fiquet Cézanne had a strained relationship, marked by periods of physical separation and emotional isolation. Despite their differences (or mutual indifference), Fiquet Cézanne repeatedly posed for Cézanne, albeit under circumstances and terms unknown now (figs. 9, 10, 11).

Due to the repetition of her wardrobe, many Fiquet Cézanne portraits record a series of moments seen and painted in quick succession. Across these series, Cézanne attended to the way she turned and shifted. The National Gallery displayed three of the Fiquet Cézanne series: respectively, 1877, 1885–86, and 1888–90. In the 1885–86 series showing her in a high-necked blue dress, the exhibition placards described these portraits as Cézanne’s rejection of conventions due to her severe hairstyle, shapeless dress, and blank expression. Insisting on Cézanne as the actor and Fiquet Cézanne as the acted upon, however, privileges Cézanne-the-artist and Cézanne-the-man. It denies the possibility of Fiquet Cézanne’s choice: that she selected her outfit and hairstyle and preferred to be represented thusly. With her one eye more focused and fixed on Cézanne (and so on me outside the frame) and her other eye tired, small and sunk beneath a heavy brow, in the 1885–86 series, Fiquet Cézanne seems absorbed in thoughts and emotions more complex than permitted by the placards (fig. 12).

Compared with the placards’ somewhat reductive descriptions of Cézanne and Fiquet Cézanne’s personal and work relationships, the catalogue underscored the complexity and dynamism of their connection as visualized by these series, which were couched as crucial to the exhibit’s intervention:

Cézanne’s creation of pairs or series of portraits of the same sitter [are] something previous curators have tended to avoid (with the exception of the 2014–15 exhibition of portraits of Madame Cézanne at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York).[11]

Admitting that Fiquet Cézanne’s physiognomy or expression often seem “impossible to specify,” Elderfield abstained from reading their artist-model/muse/wife relationship as fixed across time and instead emphasized that the affect of these portraits shifts across and within the series, moment by painted moment. Questioning the artist’s and Fiquet Cézanne’s negotiation in the 1885–86 series, he concluded that Cézanne, as the artist, “obviously controlled the portraits mode of address.”[12] But, in the next stroke of his pen or keyboard, Elderfield reversed his conclusion, writing that these paintings intone a type of collaboration between the sitter and the artist: “We feel no clear line between the painter’s control and the sitter’s self-presentation. Such a portrait—one that affords the sitter, with the cooperation of the painter, the means of presenting him or herself—speaks of a quality of intimacy between the two, whether or not the presentation they collaborate to produce also expresses mutual affection.”[13] Turning back to the portrait as a painted object, he ultimately demurred that “the closer the subject to him, the more condescending a benevolent painting would be. And Hortense is painted as extremely close.”[14] This issue here comes not with Elderfield. It comes with our desire to affix a single interpretation to the relationship existing and evolving outside the picture plane.

Even in the earliest and arguably tenderest portrayals of Fiquet Cézanne from 1877, when she poses dressed in a shimmering blue and green striped skirt and seated in a chaise sewing, she looks away, introspectively turning her eyes downwards to her sewing or distantly outwards beyond the picture plane. In one painting from this series, she directs her stare outwards (fig. 13). In this instance, Cézanne would be the object of her gaze, as much as she would be the object of his. In a portrait from the 1885–86 series, Madame Cézanne in Blue, this cool assessment has been maintained, extended, or strained to the point of pain or boredom (see fig. 12). We may wish to read her pursed lips as signaling a deepening dissatisfaction or an emotional chasm between the two—a distance exacerbated by the physical proximity of Cézanne to Fiquet Cézanne. Across these series spanning the decades, I see Cézanne through or with Fiquet Cézanne as drawing out the differences between intimacy and proximity. As Elderfield has incisively noted, a portrait like Madame Cézanne in Blue must have required the artist to pull his easel or stool incredibly close to Fiquet Cézanne, so as to scrutinize her face and form, all the while denying the details of what he has seen and studied. Such a painting reveals the critical difference between physical closeness (proximity) and emotional distance.

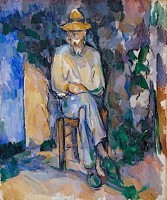

In the last decade of his life, when he lived apart from Fiquet Cézanne, the artist turned his paintbrush to his servants and peasants in Provence. Lightening his touch in paintings like The Gardner Vallier, Cézanne dissolved the figure, making him into an abstracted, playful patchwork of dappled, bright color and varied strokes (fig. 14). Other portraits after Vallier represent him in profile, with his hands patiently folded and placed in his lap. In paintings like these, executed at the sunset of his life, Cézanne seems at his most Impressionist. With his eyes shaded by his straw hat and slight curl that crosses his lips—a small smile reminiscent of Choquet who struck a similar pose—Vallier’s casualness attests to the artist’s comfort with those from different ranks and classes. While a servant like Vallier may be more comfortably labeled a worker, all of those portrayed by Cézanne worked for him—and, as Vollard attested, posing for a portrait could be physically exhausting work. From Geffroy and Vollard who promoted him, to Fiquet Cézanne who repeatedly acted as a model, to Paul fils who later secured contracts for him, all these people labored for the artist as he made them into his work (fig. 15).

Though scholarly debate continues to swirl around how to interpret these portraits in connection to Cézanne’s biography, personality, and prescribed social alienation, the National Gallery has thankfully abnegated questions about whether Cézanne’s portraits constitute factual or accurate portrayals of physical likeness—queries easily resolved via side-by-side comparisons with other artists’ paintings of the same sitters, photographs, or other visual records. These types of comparisons would only lead to facile discussions about the artist’s success or failure behind the easel. Cézanne Portraits instead pressed that his “paintings often seem to question the very aim of portraiture.”[15] The question of these noncommissioned and private portraits’ purpose and accomplishment has been opened to the public who attended and who, like me, may have viewed them through the lens of current discourses around social media and the curation of our private selves and lives put on (semi-) public display.

Post-Script:

In my time spent taking notes in the National Gallery, I realized that I studied not only the people portrayed by Cézanne, but also those in attendance primping and posing to snap selfies to share on their digital social platforms and with their digital networks. A stark chasm emerged between those who formerly posed to be painted by Cézanne and those who now posed to be photographed by themselves or their friends. Whatever may be said about his portraits as formal experimentations, daringly pushing portraiture beyond physical semblance and representation, Cézanne did not idealize or beautify these highly private portraits. Not even in his self-portraits where he stares confrontationally out from the picture plane—the only person to be painted by him whose eyes he steadily or fully met (fig. 16). In these self-portraits, he painted his face with a ferocity that makes it difficult to look away. Loosing his paintbrush and palette knife onto his own form and on his social network, Cézanne may be said to have constructed those closest to him as thoroughly uncomely. With rare exception, his family, literary friends, and the servants and residents of Provence who posed for him are distorted and disheveled, flattened but never flattered, marked by uneven, underdeveloped, or occasionally pitted, wrinkled, or bulbous facial features with indiscriminate stumps for fists and smears and smudges for eyes. But, with the quick click of their cellphone cameras, those in the twenty-first century wished to see themselves portrayed, perceived, and memorialized as beautiful (however defined) and, presumably, in posing against a Cézannesque backdrop, cultured. Observing all these selfies snapped before Cézanne’s portraits—anecdotally, his self-portraits were often chosen as though to pose with the artist—only leads to more ponderous and, perhaps, plodding questions: As the line between the public and the private has blurred, what about contemporary practices of self-portraiture and social media sites such as Snapchat and Instagram separate us from Cézanne’s painted portraits and self-portraits? Is it that we produce, curate, or control our image—an image constructed and broadcast across social media’s platforms to our personally selected publics—where those who posed for Cézanne ceded the production, circulation, and interpretation of their images to the artist? What did it formerly mean to pose for Cézanne in these private portraits kept from the public’s eyes? And what does it now mean to snap a selfie with Cézanne?

Alexis Clark, PhD

Research Scholar in Residence, Duke University

alexis.clark[at]duke.edu

[1] Susan Sidlauskas, Cézanne’s Other: The Portraits of Hortense (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 1.

[2] Nicholas Cullinan, Earl A. Powell III, and Laurence des Cars, “Director’s Forward,” in Cézanne Portraits, ed. John Elderfield (London: National Portrait Gallery Publications, 2017), 6.

[3] For a discussion of Duranty’s conception of psychological portraiture, see Edmond Duranty, La nouvelle peinture: À propos du groupe d’artistes qui expose dans les galleries Durand-Ruel (Paris: E. Dentu, 1876); translated in Charles Harrison, Paul Wood, and Jason Gaiger, eds., Art in Theory, 1815–1900: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1998).

[4] As examples of some of the recent work interrogating Cézanne’s portraits, see Tamar Garb, The Painted Face: Portraits of Women in France, 1814–1914 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007); Heather McPherson, “Cézanne: Self-Portraiture and the Problematics of Representation,” The Modern Portrait in Nineteenth-Century France (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001); and Sidlauskas, Cézanne’s Other.

[5] Quoted from the exhibition’s introductory text panel.

[6] There has been extensive research into this portrait as well as into Cézanne’s portrait of Paul Alexis Reading a Manuscript to Zola. While that literature remains too extensive to cite here, I would call the reader’s attention to notable recent work. See André Dombrowski, Cézanne, Modern Life, and Murder (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), and André Dombrowski, “Cézanne, Manet, and the Portraits of Zola” in Interior Portraiture and Masculine Identity in France, 1789–1914, ed. Heather Belnap Jensen (London: Routledge, 2011). See also Anne Higonnet, “Manet and the Multiple” in Is Paris Still the Capital of the Nineteenth Century?, eds. Hollis Clayson and André Dombrowski (London: Routledge, 2016).

[7] John Elderfield, “Introduction: The Readings of a Model,” Cézanne Portraits, ed. John Elderfield (London: National Portrait Gallery Publications, 2017), 12.

[8] For an excellent discussion of this exhibition as well as the artist and dealer’s working relationship, see Robert Jensen, “Vollard and Cézanne: An Anatomy of a Relationship,” in Cézanne to Picasso: Ambroise Vollard, Patron of the Avant-Garde (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007).

[9] Vollard publicized his relationship with Cézanne through a series of books published in the pre-WWI and interwar period. For examples, see Ambroise Vollard, Cézanne’s Studio (New York: The Liberty Print Shop, 1915); and Ambroise Vollard, Paul Cézanne: His Life and Art, trans. Harold L. Van Doren (New York: Frank-Maurice, 1926).

[10] The international networks established by Paris-based dealers such as Vollard has been the topic of recent study by Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, amongst many other scholars. See Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, “Provincializing Paris: The Center-Periphery Narrative of Modern Art in Light of Quantitative and Transnational Approaches,” Artl@s Bulletin 4, no. 1 (2015): Article 4. Prior to Joyeux-Prunel, Robert Jensen took up the topic of Central European dealers and exhibitions’ connections to Paris. See Robert Jensen, Marketing Modernism in Fin-de-Siècle Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997).

[11] Cullinan, et. al, “Director’s Forward,” 6.

[12] John Elderfield, “Introduction: The Readings of a Model,” Cézanne Portraits, ed. John Elderfield (London: National Portrait Gallery Publications, 2017), 24–25.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Quoted from the exhibition’s introductory text panel.