The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Easy Virtue: Prostitution in French Art, 1850–1910

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

February 19–January 17, 2016

Previously at:

Orsay Museum, Paris under the title of Splendours and Miseries, Prostitution in France, 1850–1910

September 22, 2015–January 17, 2016

Catalogue:

Easy Virtue: Prostitution in French Art, 1850–1910.

Nienke Bakker, Isolde Pludermacher, Marie Robert, Richard Thomson, Aukje Vergeest.

Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2016.

192pp.; 95 color illustrations; 79 b&w illustrations; checklist; bibliography; index.

21.15€

ISBN/EAN 978 90 79310 60 9

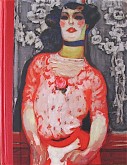

ISBN/EAN Dutch edition: 978 90 79310 59 3 (fig. 1)

On entering the Easy Virtue exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, a visitor was confronted by a number of significant issues that needed to be understood before continuing the journey through the show itself. The first of these issues involved what is actually meant by the title of the exhibition. The title begs the question: what is so easy about virtue or was virtue something that was continually lost by women in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries? More pressing than this is how the show related to one of the main themes of the nineteenth century: prostitution. How was prostitution viewed at the time, how widespread was it, and were prostitutes found everywhere or only in certain locations? Once these points have been examined, the ways in which artists suggested the presence of a prostitute in their works from the 1860s onward can be seen and studied. The latter is actually the theme that was first addressed in the show itself while the other issues just raised were left to the catalogue or not addressed at all. The reduced version of the catalogue published for the Van Gogh Museum venue of the exhibition would have been best read before entering the show as it makes some issues clearer than the majority of the wall texts positioned either next to paintings or as texts singling out some of the thematic sections of the show (figs. 2, 3, 4).

In the first large wall text, prostitution was described as a “fascinating subject for artists” without clarifying why this was the case. Setting the stage for the exhibition, the text continued by stating that prostitution was “not to be visible” as “polite society” was shielded from it, ostensibly because it was generally agreed that the sex trade was not to be actively shown in works of art. In support of this thesis the exhibition began with a monumental painting by Ernest Duez entitled Splendor, part of a diptych that was first exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1874 (fig. 5). Here the case was made that one could only identify this woman as a prostitute because of her slightly “raised skirt” and her “elusive smile,” suggesting that other artists who used these visible signs were alluding to the fact that the women so depicted were active in the sex trade. In probing more forcibly into the history of this painting, the fact that it was part of a diptych, where the other section was known as Misery, revealed the eventual decay and degeneration of the prostitute who fell into impoverishment at the end of her days. While the excellent Van Gogh Museum catalogue alludes to the importance of this other part of the canvas, one that completes the implied warning of prostitution as something to be wary of, this sense of misery was not immediately conveyed in the exhibition itself. Misery was also not mentioned in the object’s wall text. Why was this? If the artist intended to offer a cautionary narrative about how momentary monetary pleasures might lead to a life of dissipation, perhaps even to being forced into prostitution to survive, then it would seem crucial to acknowledge that objective at the outset. By not discussing the “misery” that can result from the “splendor,” the viewer was misled about the purpose of the original painting.

In using the detail of prostitutes slightly lifting their skirts to reveal an ankle or leg, other images could have been added at this point in the exhibition. These included a drawing by François Bonvin of a Prostitute on the Quay “from the 1860s where this realist artist used one of the signs of prostitution in a bleak, somber drawing in ink to convey the life of a prostitute on the street looking for any customers” (fig. 6). At the same time, the implication that the sex trade was not to be graphically presented in the 1860s must be severely questioned. Edouard Manet’s Olympia (referenced later in the exhibition through a small print of this work) was anything but veiled prostitution. This was a blatant picture of sex for sale, a woman exposing herself, almost as if she were in a shop window, for any consumer. Appearing in 1865, the painting caused a controversy that is well known, but this painting needed to be placed directly in front of the viewers as they entered the show. Clearly a difficult, if not impossible, loan to obtain from the Orsay Museum, Olympia nonetheless needed to be discussed at the beginning of the exhibition where it could have set the stage for further discussion of images of the sex trade that would later define a significant part of the nineteenth-century art market in Paris. Why this was not done is a disturbing aspect of the Van Gogh Museum’s hanging of the show.

Other works from this section of the show illustrated ways in which artists signaled how a prostitute attracted customers, either by having a job where an onlooker tried to get the attention of a young girl as in James Tissot’s The Shop Girl (1885) or in works by Jean Béraud, such as the one in which a young girl waiting on the street eventually finds a male customer. These paintings seem potentially plausible in telling the story of prostitution in the city, but another work in the same section did not. In P. A. J. Dagnan–Bouveret’s Paris, Quayside in Autumn the wall text—as well as the catalogue—grossly misinterpreted the work (fig. 7). As two well-dressed young men walk along the Parisian quay they notice a young washerwoman holding onto her basket. But instead of eyeing the woman as an object for sex, these men walk arm in arm, holding onto each other. They are gay, blatantly so, and their identities are known: the taller of the two is Gustave Courtois (1852–1923) and the other is Carl Stetten (1857–unknown death date), a German artist. Both were in the same ateliers at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and both would become well known as fashionable artists, but they were part of the gay scene then close to Dagnan-Bouveret. To interpret their gazes, their glances, in the way that the text did is to misinform.

Walking through the “Uncertainty and Ambiguity” section attention focused on two paintings by Louis Anquetin. Both Woman on the Champs Elysées at Night (1891) and Woman with a Veil (1891) show how artifice, dresses, and lighting increased the attractiveness of a streetwalker. While the Van Gogh Museum catalogue does a good job of presenting these paintings in the essay “The Spectacle of Prostitution,” a further reading of the paintings might reveal whether these women were really prostitutes or if their dress signaled that they could be enticing cross-dressers. This aspect of prostitution was not discussed in this show at all.

In the second major thematic area of the show, “Cafés and Theatres as Meeting Place,” the focus shifted from the streets to the new areas where assignations were possible. According to the didactic wall text, “Places of Entertainment served as a front for prostitution,” and sites such as the Moulin Rouge or the Moulin de la Galette served as locations where women picked up clients. This phenomenon was further reinforced by seeing “prostitutes with their pimp” as in paintings such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s image of the interior of the Moulin de la Galette (1889). But in doing this, the exhibition fell into a dangerous trap: were all these locations the sites where prostitutes gathered? Was every a performer therefore a prostitute? Is the femme fatale synonymous with the prostitute? Was the exhibition seeing too many prostitutes? In order to reinforce some of these interpretations, the exhibition included photographs of prostitutes displayed in a glass case side by side with a “Register of Courtesans” from the Archives de la Préfecture de Police in Paris (fig. 8). This very significant document, with photographs of the presumed courtesans alongside their characteristics, provided tangible evidence of the number of prostitutes in Paris and the fact that they had to be registered with the police department in order to practice their trade. Unfortunately, placed in a case that was poorly lit, it was difficult to decipher and a visitor might have passed it by without looking at it at all. It also cried out for much further interpretation in the show, not just being reproduced in the Van Gogh Museum version of the catalogue (no. 114).

From this area emerged the next thematic area “The Splendor of the Courtesans.” Here, elaborately kept women were seen as manipulating their public pose. Paintings emphasized the way they were dressed; the inclusion of an elaborate, large-scale bed possibly used by La Paiva, one of the most dominant courtesans of the time, shed further light on a higher class of prostitute—one who had graduated from the street to an elaborate townhouse. This emphasized one of the more difficult aspects of the show—how to visualize the rooms, houses, and clothing of a wealthy courtesan. Paintings for this section seemed inadequate, and a vitrine with important “instruments of seduction” was buried in a corner of the installation, again suggesting that actual documentary evidence of what happened inside a house, how pleasure was meted out, was not thought to be of central importance especially since these objects were not adequately interpreted in a wall text (fig. 9).

In the midst of these last two sections stood one of the most important of all nineteenth century paintings Absinthe Drinker (1875–76) by Edgar Degas, a work shown with the Impressionists that has been widely examined by generations of art historians in publications and lectures. It has never been seen as a work that depicts a prostitute sitting in a café, hopefully looking to find a customer. Rather, the work emphasizes the role of absinthe in creating an atmosphere of dissipation that led to actresses such as Ellen Andrée shown here with Marcellin Desboutin, the artist next to her, as being intoxicated by drink. The wall text in the exhibition proposed another interpretation of this seminal work, suggesting that “in . . . the early evening many Paris prostitutes sat in cafés, sipping this famous bright green drink as they waited for clients. Respectable women never frequented such establishments. This woman looks worn out, and has even bent her ankles to give her feet a rest. Perhaps she is an unregistered prostitute taking a rest from her street walking?” Was this a case of once again seeing too many prostitutes everywhere in Paris? The evidence for this work, the inclusion of a well known artist as the male model and an actress exhausted from her actual work, moves one in another direction. The wall text pushed into a fantasyland of bending material to a preordained end without closely examining the content and context of this superb painting of urban dissipation and the dangers of drink—one of the other major issues affecting individuals in the nineteenth century (fig. 10).

There can be little doubt after going through this first large section of the show that confusion reigned. The themes were not clearly developed and, even more critically, the history of prostitution in France needed far more historical context to provide a viewer with the time to absorb what was presented. Admittedly, prostitution is a crucial topic, but the visitor was in no way prepared to understand how it flourished in France without a much deeper integration of history with the painted images. In addition, reference needed to be made to the considerable literature on prostitution done by American scholars. With this noted, examination of the second part of the exhibition was essential.

The exhibition continued on the second floor of the museum with the section titled “From Anticipation to Seduction.” Here, the exhibition became more fully focused. Scenes from brothels were displayed, interest in what actually happened at these sites and concern with the prostitutes themselves emerged forcefully through works by Jean-Louis Forain and especially the sensitive, often very moving, works by Toulouse-Lautrec (fig. 11). Located near these scenes were a number of brothel documents: tokens, calling cards itemizing how to contact a given girl, and special condoms (fig. 12). A photo album from ca. 1900 contained a text that revealed how those brothels that “were tolerated” and “which required women to actually live inside were gradually replaced by maisons de rendez-vous, where women worked, but did not live.” This particular album of photographs was one of the most significant documents in the exhibition; and in this case, it was not hidden away in some corner of the show. It was also exceedingly well explained as it showed how a girl could be selected “before-hand.” At the same time, this album made clear to a potential customer that a brothel could offer women of all descriptions with “regard to looks as well as character” (fig. 13). As part of this area, different types of women were revealed in images by the Belgian artist Félicien Rops who saw many prostitutes as examples of a femme fatale—a dangerous modern woman who posed a threat to the existence of men. But other images, especially the prints and monotypes of Edgar Degas, movingly revealed what life in a brothel was like as they conveyed the claustrophobic closeness of the setting through the anguished, and often anticipatory, features of a given girl. These works by Degas, never publicly exhibited in his lifetime, remained among the most moving of all the works in the exhibition (fig. 14).

The show also tellingly recreated the issues of health and contagion surrounding the increasing number of prostitutes. Frequent examinations, washing of the women as in a work by Forain, revealed the ways in which prostitutes were monitored. The French regulatory system was exacting since there was a concerted effort to try to contain illness, especially the problem of syphilis. By carefully monitoring prostitutes it was believed that the fear of contagion among men would be assuaged, but in the end this system was seen as a failure. The women who were infected were sent to the St. Lazare prison, a location emphasized in a superb work by Toulouse-Lautrec and later by Pablo Picasso (not strongly represented in the show) during his Blue Period when he used the women in St. Lazare as his models (fig. 15).

Alongside this section of the exhibition the organizers placed revealing photographs, many of which were posed in brothels to demonstrate what occurred there. For the first time in the show, photographs were exhibited to show actual sexual activity. As is tellingly chronicled in the exhibition catalogue, there was a conflation between the artists’ perception of a woman as a prostitute and as a model. They were conjoined in this way, as is often reflected in works by Picasso. At the same time Picasso’s works were presented as a means of visualizing sexual debauchery, a quality strongly emphasized in his treatment of Gustave Coquiot, one of his early defenders who is seen as a Mephistophelean figure positioned in front of a frieze of sexually active women. Moving from the bordello photographs to paintings of more frenzied sexual activity would have been facilitated better by having more references to Picasso’s powerful Demoiselles d’Avignon, but this, as was the case with Manet’s Olympia, was not possible to obtain for the show although its powerful presence was missed at the Van Gogh Museum (fig. 16).

At this juncture, a visitor could move into the film salon where a movie examined a number of the themes that the exhibition tried to elucidate. While the film was adequate, the way in which people were supposed to see the film was inadequate. There were few places to sit, and when a large number of people were looking at the film, there was no way to see over or around a tall figure. If the film was not enticing, then the last section of the exhibition was ready to be seen. This area, identified as “Debauchery in Color and Form,” presented an abundance of images of prostitutes used by any number of painters working in the early twentieth century.

This part of the show also seemed somewhat unresolved. The wall text posited that after 1881 there was “more openness of prostitution” as the prostitute was now “seen as an individual.” This statement, however, clashed directly with what was seen in the section on the brothels where the women in both Degas’s prints and Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings were individualized in the extreme. So what exactly, then, was this section of the show trying to achieve? In examining some of the works, abstraction was becoming a dominant mode in creativity. Paintings such as Jan Sluiters’ Women Kissing revealed a new type of focus: the perverse pose. The intimacy of the composition makes it clear that prostitution of various kinds, essentially that of lesbians, contributes to the openness of the era. Other paintings, by František Kupka, Kees van Dongen or André Derain, demonstrated through violent color and distortions of form, the expressiveness of tormented, tortured lives. These points are valiantly referenced in the catalogue essay, albeit not with clear resolution, as an effort to examine the debauchery of these works in color and form predominates (fig. 17).

The exhibition closed with an excellent, albeit small exhibition titled “Prints-Privacy-Prostitution” by the Van Gogh Museum Curator of Prints and Drawings, Fleur de Rose Cavalho. This modest exhibition focused on those prints that were done privately out of sight of the censors or moralists. Works by Rops or Louis Legrand were featured. A second theme presented the “Beauty of Perversity” showing the full impact of the writings of Charles Baudelaire. And the show closed with excellent examples of Symbolist imagery in the works of Georges de Feure, Forain, and Albert Besnard. As an addendum to the larger exhibition, this focused show pointed out that many of the same themes as found in paintings were addressed in the world of prints.

The excellent small catalogue for the Van Gogh installation provided easy to read texts, with a substantial thematic arrangement, that proved useful to anyone visiting the exhibition, but it should have been read beforehand in order to increase the appropriate contextualization for the exhibition.

With this understood, what then are the contributions of Easy Virtue and what might have been considerably improved? There is little doubt that the concept of prostitution, its societal implications, and the range of prostitutes in Paris was a substantial topic for an exhibition. But in order to make this theme comprehensible to the public, it would have been necessary, even appropriate, to provide a historical overlay to start the show. Without this, a visitor had a tendency to get lost, especially in the opening gallery of this installation. The inclusion or re-creation of various types of rooms in a brothel—a Turkish room or a Chinese room for example—would have given a viewer a fuller picture of the fantasy that brothels provided. Without this, not enough attention was focused on specific types of seductions and the locations where they took place. The selection of objects, while appropriate, was also difficult to gauge, as there could have been many more prints used as well as photographs of actual prostitutes integrated into the matrix of the presentation. All in all, this was a challenging effort, a first step in trying to elucidate a very difficult topic, but a theme that still awaits deeper, fuller clarification in order to grasp the range of implications of prostitution and its effect on the visual arts in this period of time.

Gabriel P. Weisberg

Art History Department, University of Minnesota

Vooni1942[at]aol.com