The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Vigée Le Brun: Woman Artist in Revolutionary France

Réunion des Musées Nationaux – Grand Palais, Paris

September 12, 2015–January 11, 2016

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

February 9–May 15, 2016

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

June 10–September 12, 2016

Catalogue:

Joseph Baillio, Katharine Baetjer, and Paul Lang.

Vigée Le Brun: Woman Artist in Revolutionary France.

New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015.

288 pp.; 166 color illustrations; bibliography; index.

$50

ISBN: 9781588395818

Exhibition trailer:

Vigée Le Brun: Woman Artist in Revolutionary France is the first international retrospective dedicated to painter Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842). Staged at the Grand Palais in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, the exhibition was a chronological presentation of works from throughout Vigée Le Brun’s career as an elite portraitist, which coincided with one of the most tumultuous periods of French history. Despite the relative uniformity of her subject matter, Vigée Le Brun’s oeuvre is diversified by the various personalities and materials, which she reproduced on canvas. This exhibition highlights the remarkable textural specificity of her paintings: the moistness of lips just licked, the iridescent sheen of silk, the fashionable frizz of a carefully constructed coif.

Vigée Le Brun is perhaps the most widely known of the four female artists admitted to the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in the final decades of the Ancien Régime.[1] Since Joseph Baillio’s 1982 exhibition catalogue, however, Vigée Le Brun has been the subject of relatively few scholarly studies—notably, Mary Sheriff’s The Exceptional Woman: Elisabeth Vigée -Lebrun and the Cultural Politics of Art (1997) and Gita May’s Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun: The Odyssey of an Artist in an Age of Revolution (2005).[2] The primary biographical source is the artist’s own Souvenirs, which was written and published in three volumes between 1835 and 1837.[3] Although unabashedly self-promoting, Vigée Le Brun’s memoirs offer fascinating insight into the theatrical ‘acts’ of her life—her childhood and academic career in Paris, and her travels throughout Europe and Russia after the French Revolution. This first-person biographical account, rare among artists of her time, is particularly exceptional among her female contemporaries at the Académie, most of whom left little written material to the historical record—let alone a self-conscious articulation of her own personal narrative.

Similarly, this exhibition offers audiences in Paris, New York, and Ottawa unprecedented access to works by Vigée Le Brun. The exhibition was curated in Paris by Xavier Salmon, Director of the Graphic Arts Department at the Louvre Museum, and Baillio, an independent art historian who is preparing the artist’s catalogue raisonné. The show was adapted in New York by Katharine Baetjer, Curator in the Department of European Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[4] Baillio, Baetjer and Paul Lang, the Deputy Director and Chief Curator at the National Gallery of Canada, collaborated on the English version of the exhibition catalogue.

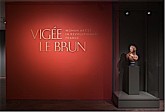

The New York iteration of the Vigée Le Brun: Woman Artist in Revolutionary France featured 80 works, approximately a third of which are from private collections; many of these had never been exhibited publicly before. The show is heralded by the only three-dimensional work in the exhibition: a terracotta portrait of Vigée Le Brun by the academic sculptor Augustin Pajou (1703–1809) set against a bold, blood orange colored wall emblazoned with the artist’s name in gold (fig. 1). Pajou’s sympathetic, informally styled bust, which seems to corroborate contemporary accounts of the artist’s physical beauty, dates to 1783, the year Vigée Le Brun was admitted to the Académie.[5]

Visitors are subsequently confronted with a monumental portrait of the artist’s most notorious patroness (fig. 2). Marie Antoinette in Court Dress was painted in 1778, when Marie Antoinette, four years a queen, and Vigée Le Brun were both twenty-three years old (72). The very size of this painting indicates the prestige of the commission for the ambitious young artist—the portrait was intended as a gift for Marie Antoinette’s mother, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. Executed five years before Vigée Le Brun became an académicienne, this rather stiff early painting betrays the unwieldiness of the formal regalia required by the French court. The grand habit de cour (grand court dress) consisted of a grand corps (a restrictive corset), wide paniers (a structured undergarment attached to the hips), and a silk gown made heavy with fussy bows and swags of white satin.[6] Marie Antoinette also sports an elaborate pouf, the controversial, towering coif that she helped to popularize. In her hand, she holds a single pink rose—her favorite flower, and a symbol of the Austrian branch of the Hapsburg family from which she hailed. The portrait is made additionally awkward by the specter of Marie Antoinette’s increasingly corpulent husband—here in the form of a marble bust placed on a pedestal above the queen’s head. The representation of Louis XVI in this portrait of Marie Antoinette is an apt metaphor for the tensions that existed between the two; their failure to consummate their union in their first seven years of marriage was a constant source of anxiety and embarrassment for both.[7]

The portrait is nevertheless compelling as early evidence of the connection between Marie Antoinette and Vigée Le Brun, two young women mired in unhappy marriages of political or professional convenience, who were both considered ‘outsiders’—Marie Antoinette as an Austrian reigning over a rather xenophobic Versailles, and Vigée Le Brun as an aspiring painter in a field dominated by men. The relationship between the monarch and the artist (recently dramatized and eroticized in Joel Gross’s play, Marie Antoinette: The Color of Flesh) would prove mutually definitive: Vigée Le Brun would be responsible for some of the most iconic images of the ill fated monarch, who in turn advocated for Vigée Le Brun’s acceptance to the Académie in 1783.[8]

This first room of the exhibition is also replete with (much smaller) portraits of the artist’s family, also dating to the 1770s: her mother, Jean Maissin Le Sèvre (a hairdresser, who encouraged her daughter’s professional aspirations); her younger brother, Etienne Vigée (whose revolutionary politics would later estrange him from his older sister); and her stepfather, Jacques François Le Sèvre (a goldsmith, with whom the artist had a rather contentious relationship) (fig. 3). The only familial likeness missing is that of Vigée Le Brun’s father, who died when she was twelve years old. Louis Vigée had been a painter and a member of the Académie de Saint Luc, and it was likely he who provided her initial training (4–5).

Vigée Le Brun is best known for her portraits of women, and the exhibition is dominated by examples of these. Yet the representations of the men in Vigée Le Brun’s family—as well as the admiring portrait of her rather handsome first teacher, landscape painter Joseph Vernet (1714–89)—indicate the profound role that men played in her early formation as an artist (fig. 4) (70). Her elite patronage network was certainly not limited to the members of her own sex; she executed several commissioned portraits of powerful aristocratic men, including the Prince de Nassau-Siegen (1776), the Comte de Vaudreuil (1784), and the minister of state, Charles Alexandre de Calonne (1784)—all of which are on view in New York. Perhaps the most vigorous likeness in this group is that of chevalier Alexandre Charles Emmanuel de Crussol-Florensac—painted in 1787, when the artist was at the height of her powers (fig. 5). According to her Souvenirs, it was the payment for this portrait that facilitated her flight from revolutionary Paris in 1789 (131).

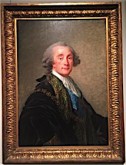

The artist’s relationship with her husband, Jean Baptiste Pierre Le Brun (1748–1813), an art dealer and a distant relative of a founding member of the Académie, Charles Le Brun (1619–90), was more complicated (fig. 6). The marriage, in 1776, may have initially seemed to be a strategic professional move, and it was through him that Vigée Le Brun gained access to prestigious private art collections in Paris, as well as to potential patrons (237). However, it was also because of her husband’s profession that Vigée Le Brun’s application to become a member of the Académie initially stalled; certain academicians objected to any commercial taint within the elite institution. It was only through the intervention of the queen that Vigée Le Brun was admitted on May 31, 1783—the same day as Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803), a portraitist of comparable ambition and talent.[9]

These two female artists have traditionally been positioned as rivals, although any antagonism between them has likely been exaggerated by both eighteenth-century criticism and modern scholarship. As Danielle Rice wrote in her review of the Labille-Guiard catalogue raisonné, “The concept of rivalry . . . served as an effective device for isolating the two women, deflecting attention away from the threat that feminine talent and success made to male supremacy in the arts.”[10] It should be noted, however, that Vigée Le Brun does not mention Labille-Guiard in her Souvenirs, a text that is otherwise thick with name-dropping.[11] Perhaps accordingly, the exhibition does not include any work by Labille-Guiard—despite the fact that the Met owns the latter’s most iconic work, a self-portrait of the artist seated at her easel, flanked by two female students (fig. 7). The catalogue does feature an essay by Baetjer summarizing female participation in the Académie in the eighteenth century, yet these other pioneering female artists receive little or no mention in the exhibition itself (33–45).

To the Salon of 1783, her first as an académicienne, Vigée Le Brun submitted several portraits, as well as her morceau de réception (reception piece), Peace Bringing Back Abundance (fig. 8). The canvas depicts two buoyant allegorical figures: a placid brunette representing Peace, swathed in billowing silks, escorts the blonde, bare-breasted figure of Abundance, who proffers a cornucopia of fruits and flowers. Sheriff has suggested that this allegory was a reference to the recent peace treaty ending France’s involvement in the American Revolution. Yet the painting is also an explicit statement of the artist’s ability to paint complex mythological subjects, a genre considered more prestigious than portraiture.[12] A vivid pastel study for the figure of Abundance is also included in the exhibition—regrettably, not alongside the painting that it prepared, but rather in the nook of a subsequent gallery dedicated to the artist’s works on paper (fig. 9).

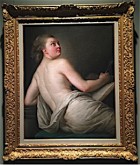

The intimate embrace and mutual gaze that unites the fleshy figures of Peace and Abundance, unburdened by gravity and endowed with allegorical meaning, is practically Sapphic, which might strike the twenty-first century viewer as rather bold. Yet this was not the first or last time that Vigée Le Brun painted the mythological female body; a nude female Allegory of Poetry (1774) is on view the first gallery, and a bust-length canvas of a flushed, topless Bacchante (1785) is in the third gallery (figs. 10, 11). The implications of a female artist painting a nude female body—perhaps the artist’s own, or that of a hired model—might have been explored more fully here (67). Vigée Le Brun’s work could be compared, for example, to that of Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807), a member of the Royal Academy of Arts in London who also exhibited paintings with exposed breasts in the late eighteenth century.[13]

Any objections to the nudity in Vigée Le Brun’s allegorical morceau de réception were probably overshadowed by a different controversy at the Salon of 1783: Vigée Le Brun’s portrait of the queen en chemise, a gauzy white gown, as well as a straw hat accented with a thick gray plume (fig. 12). The chemise represents the Marie Antoinette’s predilection for the ‘rural’ delights of the Petit Trianon, where she was free from the formal constraints of the palace of Versailles. Here, the rose in her hand here alludes not only her Hapsburg heritage, but also her love of gardening—just one of the pastoral fantasies that she performed at the Petit Trianon (87).[14]

Visitors to the Salon of 1783 were shocked by the causal intimacy of the queen’s costume in Vigée Le Brun’s portrait; the resulting scandal prompted the artist to quickly paint a replacement. The second painting is of the same composition and slightly larger dimensions, but the queen is more conservatively attired: a luxe silk gray gown, fringed with exquisitely rendered lace at the neckline and at the elbows (fig. 13). The queen’s hair was also altered: it is more heavily powdered and precisely curled, and adorned with a more formal bonnet of ribbon.[15] The twin portraits—the first from Hessiche Hausstifung in Kronberg, and the second from a private collection—are displayed side by side for the first time here, in what is perhaps the most striking moment in the exhibition.

In each of these portraits, Vigée Le Brun and Marie Antoinette seem to have collaborated in the styling of the royal body and coif—and thus, in the construction of the queen’s public image. Marie Antoinette’s personal fondness for fashion is well known; see, for example, the scene from Sofia Coppola’s 2006 film, in which a montage of the queen’s sartorial exploits, fueled by champagne and sugar, is set against an upbeat cover of The Strangelove’s “I Want Candy” by Bow Wow Wow.[16] Yet as Caroline Weber has shown in Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution (2007), the queen’s choice of costume was inherently political; her material excesses and transgressions were a constant source of criticism, whispered about in the halls of Versailles and published in the Parisian popular press.

If the subsequent commissions from aristocratic “It Girls” are any indication, however, the scandal surrounding Vigée Le Brun’s portraits of the queen at the Salon of 1783 only bolstered the artist’s painting practice (figs. 14, 15). Moreover, these portraits suggest that the artist shared the queen’s passion for la mode. While the theme of hair and clothing is not over emphasized in the exhibition literature, the chronological installation nevertheless prompts viewers to trace the evolution of forms that fashioned female bodies, and to share the artist’s obvious fascination with the material expressions of those trends—from the tight corsets, unwieldy paniers, and elaborate poufs that characterized Louis XVI’s reign, to the airy empire waist dresses and loose, frizzy ringlets that ushered in the nineteenth century. It bears repeating, moreover, that the Vigée Le Brun’s mother was a hairdresser, an increasingly prestigious profession in the late eighteenth century; her paintings demonstrate a familiarity with, and profound respect for, her mother’s craft.[17]

Though Vigée Le Brun and Marie Antoinette’s reputations were closely intertwined by the late 1780s, a second pair of portraits of the queen charts their radically divergent fortunes thereafter (figs. 16, 17). In 1787, the artist painted the royal matriarch seated with three of her four children. According to the catalogue, Vigée Le Brun was commissioned to paint a portrait “to restore the queen’s image, lending respectability by extolling her maternal role” (121). Exhibited at the Salon of 1787, the portrait was intended to counteract the queen’s reputation as a frivolous and vain foreigner; here, she is instead presented as the mother of the heirs of France. Her oldest daughter grasps her mother’s arm with affection. Her youngest son, propped on her knees, fusses with the gold ornament at his mother’s bust. Her oldest son, the dauphin, gestures towards an empty bassinet—a reference to the fourth child, an infant daughter, who died before the painting was completed. The rather sober, melancholy painting ultimately fell short of its propagandistic goal—particularly when it was compared to Vigée Le Brun’s more cheerful, intimate group portrait of the Marquise de Pezay and the Marquise de Rougé with her two sons shown at the Salon of the same year (and in New York, on display in the subsequent gallery) (fig. 18).

The second portrait, from 1788, is nearly identical in compositional and scale—although the royal children have been excised, and the queen wears a sapphire blue velvet gown trimmed with sable, rather than red (fig. 17). Unlike its twin, this canvas was never exhibited at a Salon, but rather accompanied the artist on her flight from France amidst the revolutionary turmoil of 1789. The painting would go on to serve as evidence of the artist’s talents and elite connections while she traveled and worked abroad (248). Vigée Le Brun had built a career based on Marie Antoinette’s patronage; now, that affiliation forced her to leave France, with her daughter Julie in tow, and to use the queen’s image to solicit commissions in foreign courts. This painting is something of a fulcrum in the exhibition, a pivot into the dramatic “second act” of the artist’s life: thirteen years of exile, during which time her portrait practice flourished in the Florence, Rome, Naples, Vienna, Saint Petersburg, Moscow, and London. It is during the same period, of course, that the subject of this painting met the guillotine, in 1793.

Vigée Le Brun’s itinerary is illustrated in the form of commissioned portraits, produced as she traveled from city to city. The catalogue also provides a useful chronology, as well as color-coded map of her travels between 1781 and 1820. Perhaps the most fascinating period of this ‘second act’ was the artist’s residency in Catherine the Great’s Saint Petersburg, during which time she earned the patronage of Russian princesses and ‘celebutantes’—pictured wearing soft, richly colored peignoirs and Orientalized turbans (figs. 19, 20). At the Met, however, this section is much sparser than it was in Paris or Ottawa—due to the fact that since 2011, Russian museums have refused to lend objects to American museums.[18] As a result, several portraits from the collections of the State Hermitage Museum, the State Pushkin Museum of Art, and the State Tretyakov Gallery were only on view in Paris and Ottawa.

In addition to the commissioned portraits of wealthy, fashionable women, two other minor themes emerge in the second half of the exhibition: the artist’s self-portraits, and the portraits of her daughter, Julie. The Met hosts two excellent post-Revolution self-portraits; the first is the pastel on paper Self-Portrait in Traveling Costume, which the artist gifted to the director of the Académie de France in Rome after she arrived in 1789 (fig. 21). The second is a painting executed in 1790 for the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence, where it joined a series of contemporary artists’ self-portraits, including that of Angelica Kauffmann (fig. 22). In the words of Vigée Le Brun: “Immediately after my arrival in Rome, I did my portrait for the Florence gallery. I painted myself with a palette in hand, in front of canvas on which I am drawing the queen in white chalk” (142–3). These preternaturally youthful self-portraits are expressions of the artist’s resilience, despite the trauma of political exile, and her confidence in her own talents and charms. These works are also evidence of her determination to support herself and her daughter, in part by ingratiating herself with foreign art institutions; she would also employ a self-portrait in order to become a member of the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg in 1800 (142).

Unfortunately absent from the exhibition are two of the artist’s most iconic, pre-Revolution self-portraits. The first is a 1782 painting from the Rothschild Collection, in which the artist pictures herself gripping a palette and brushes, wearing a plumed straw hat—although a recently discovered black chalk drawing related to this self-portrait was included (10). The second is a 1786 Louvre portrait of the artist tenderly embracing a six-year-old Julie (27). The exhibition is, however, enhanced by three portraits of the artist’s daughter, aged six, twelve, and nineteen. Lang writes, “As a token of her exclusive maternal love, Vigée Le Brun portrayed her only child, Jeanne Julie Louise (1780–1819) from early childhood onward. The successive images stand as milestones in the history of a mother-child relationship that was as passionate as it was conflicted” (203).

These paintings of the artist’s daughter provoke comparison with Berthe Morisot’s late nineteenth-century paintings of Julie Manet (the subject of “A Mother Pictures Her Daughter” in Anne Higonnet’s Berthe Morisot’s Images of Women).[19] The painting of twelve-year-old Julie in the guise of a bather also prefigures Sally Mann’s photographs of her children clad in swimsuits of the early 1990s (fig. 23). [20] Though separated by a span of two hundred years, these artists all seem to probe the same line between naiveté and sexual maturity in their representations of their adolescent daughters—poignant parallels that warrant further analysis.

Vigée Le Brun did not return to France permanently until 1805; by this time, her husband, who remained in Paris, had divorced her in absentia, her daughter had married a man of whom her parents did not approve, and Napoleon had been declared Emperor of France (242). Vigée Le Brun would live until 1842—long enough to see the decline of the Napoleonic Empire, the restoration of the monarchy, and the advent of portrait photography. During that time, she continued to paint, and even secured a commission from Napoleon’s sister, Caroline Murat—although the artist had by then grown weary of the vanity and fickleness of her elite subjects (fig. 24); she complained of Murat in her Souvenirs, “The interval between the sessions was so long that she had sometimes changed her hairstyle . . . so that I was obliged to scrape off the hair I had painted around the face, just as I had to erase the headband of pearls and replace them with cameos. The same thing happened with gowns” (218).

Despite her continued productivity in the early decades of the nineteenth century, Vigée Le Brun could not help but feel that she had “outlived her time,” as the last exhibition wall text tells us. This sentiment weighs heavily on the final section of the exhibition, which is populated by a somewhat clumsy landscape and a handful of peculiar portraits. Vigée Le Brun’s own feelings of anachronism are perhaps justified by the latest painting in the exhibition, a portrait of the Duchesse de Berry, which was painted the same year as Delacroix’s Massacre at Chios (fig. 25). The catalogue only briefly acknowledges the oddities of this late portrait; Stéphane Guégan, curator at the Musée d’Orsay, writes, “Granted, Vigée Le Brun’s manner was beginning to lose its suppleness and smoothness, but the picture is not unworthy of the portraitist of Marie Antoinette” (233).

Indeed, Vigée Le Brun’s ‘moment’ had passed, and her legacy was still embroiled with that of the last queen of the ancien régime. Yet if Christie’s April 2016 sale of Vigée Le Brun’s portrait of Princess Golitsyna for $1,205,000 (an auction record for an académicienne) is any indication, this artist is now ripe for reconsideration. Vigée Le Brun situates this artist’s oeuvre in the context of her international patronage network. Complemented by catalogue essays by Baillio (“The Artistic and Social Odyssey of Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun”) and Lang (“Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun and the European Spirit”), this exhibition assesses the ways in which a Woman Artist in Revolutionary France navigated the shifting cultural and political landscape of her time.

Kelsey Brosnan

PhD Candidate, Art History Department, Rutgers University

Kelsey.Brosnan[at]rutgers.edu

[1] Vigée Le Brun’s fellow académiciennes in the 1780s included Marie-Thérèse Reboul (1728–1805), Anne Vallayer Coster (1744–1818) and Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803). See Laura Auricchio, Melissa Lee Hyde, Mary Sheriff, and Jordana Pomeroy, Royalists to Romantics: Women Artists from the Louvre, Versailles, and Other French National Collections (New York: Scala Arts Publishers, Inc., 2012).

[2] Joseph Baillio, Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun: 1755–1842 (Fort Worth: Kimbell Art Museum, 1982). See also Mary Sheriff, The Exceptional Woman: Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun and the Cultural Politics of Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997); and Gita May, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun: The Odyssey of an Artist in an Age of Revolution, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005). May, a Professor Emerita of French Literature at Columbia University, passed away on January 29, 2016, a month before the exhibition opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. See “In Memoriam of Gita May (1929–2016),” Columbia University Department of French and Romance Philology, http://www.columbia.edu/cu/french/department/fac_bios/may.htm.

[3] Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Souvenirs, 3 vols. (Paris: Fournier, 1835–37).

[4] At the press preview of the exhibition, Baetjer noted that this was the first exhibition dedicated to a female artist that she had worked on during her forty-year-long career at the Met. See the video of her remarks here: Lee Rosenbaum, “Vigée Le Brun: Flattery Got Her Everywhere, Including the Met,” CultureGrrl, February 17, 2016, http://www.artsjournal.com/culturegrrl/2016/02/vigee-le-brun-flattery-got-her-everywhere-including-the-met-with-video.html.

[5] Sheriff, The Exceptional Woman, 50.

[6] Caroline Weber, Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution, (London: Aurom, 2007), 25.

[7] Ibid., 140.

[8] See Neil Genzlinger, “How a Queen Lost Her Heart Before She Lost Her Head,” The New York Times, April 11, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/11/theater/reviews/11fles.html?_r=0.

[9] See Anne-Marie Passez, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Biographie et Catalogue Raisonné de Son Oeuvre (Paris: Art et métiers graphiques, 1973) and Laura Auricchio, Adelaide Labille-Guiard: Artist in the Age of Revolution (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009).

[10] Danielle Rice, “Review: Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Biographie et Catalogue Raisonné de Son Oeuvre by Anne Marie Passez,” Woman’s Art Journal, 6:2 (Autumn 1985) 53–55.

[11] See Germaine Greer, The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work (New York: Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 2001) 98.

[12] Sheriff, The Exceptional Woman, 121, 127.

[13] See Wendy Wassyng Roworth, “Anatomy is Destiny: Regarding the body in the art of Angelica Kauffman,” Femininity and Masculinity in Eighteenth-century Art and Culture, ed. Gill Perry and Michael Rossington (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1994).

[14] See Weber, Queen of Fashion, 160–63, and Meredith Martin, The Politics of Pastoral Architecture from Catherine de’ Medici to Marie Antoinette (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011).

[15] This second portrait is the cover of the 2016 volume, Marie-Antoinette, a collaboration between curators of the Louvre and Versailles. Hélène Delalex, Alexandre Maral, and Nicolas Milovanovic, Marie-Antoinette, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2016).

[17] See Jennifer Jones, Sexing la mode: Gender, Fashion, and Commercial Culture in Old Regime France (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2004), 88–9.

[18] See Carol Vogel and Clifford J. Levy, “Dispute Derails Art Loans From Russia,” The New York Times, February 2, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/03/arts/design/03museum.html?_r=0.

[19] Anne Higonnet, Berthe Morisot’s Images of Women (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994), 204–11.

[20] Sally Mann, Immediate Family (New York: Aperture, 2014).