The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

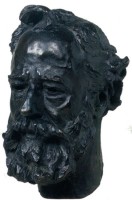

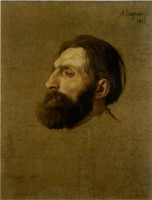

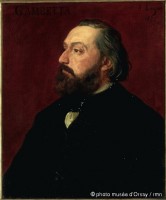

The purpose of this article is to highlight the role played by the French expatriate artist Alphonse Legros (1837–1911) in familiarizing British collectors and the British public with the work of Auguste Rodin (1840–1917). The article will show how Legros introduced Rodin to Constantine Ionides (1830–1900), a collector who in 1884 acquired Rodin’s Thinker (figs. 1, 2). Three years previously, Legros had also been responsible for acquainting Rodin with the British poet and art critic William Ernest Henley (1849–1903), editor in chief of the Magazine of Art. Henley published an article in that magazine as early as 1882, extolling Rodin as the world’s greatest living sculptor and informing British readers that Rodin was in the process of creating a set of colossal bronze doors for the Museum of Decorative Arts.[1] A year later, Henley published a print of the bust of Saint John the Baptist (fig. 3) in his magazine, the first pictorial illustration of a work by Rodin in the British press.

Rodin’s reception in Great Britain has been frequently discussed, most recently in Rodin, the Zola of Sculpture, a collection of essays published in 2004, and in the catalogue of the 2006/7 Rodin Exhibition held at the Royal Academy, which provides a full chronology of Rodin’s recognition in England.[2] Research on the Ionides Collection, in which Rodin’s work was also well represented, has similarly flourished. But while previous studies have emphasized the important roles of the critic Henley and the collector Ionides, they contain only occasional references to Legros. Yet this artist, who lived in England from 1863 until his death, was the crucial link between Rodin and the British art world.

Through a careful reading of the letters of Legros, Henley, and others to Rodin, now in the collection of the Rodin Museum, as well as of letters from Legros to Constantine Ionides, in the possession of Constantine Ionides’s heirs, the author has sought to reconstruct the relationships among the four men.[3] The letters provide compelling evidence to suggest that Legros was instrumental in establishing Rodin’s reputation in Great Britain. He urged his own patrons and supporters to acquire Rodin’s works; at the same time, he actively brought his pieces to the attention of critics and the general public. After uncovering the importance of Legros’s role, which has been previously overlooked, the author seeks to answer the question of why Legros devoted so much energy to popularizing Rodin’s works in England.

Rodin, Legros, and Ionides

Both the artist Legros and the banker Ionides live in London; I’ve suggested that they visit your atelier Monday morning at 11:00. I thought of letting you know in advance because I have been asked about works you have available and in a discussion of the bronze mask in your possession, I proposed a price of 1200 francs. Assuming that a commission will come from London, I think it is safe to say that you can ask whatever price you think is appropriate for the St. Jean.[4]

Through this letter from Jean-Charles Cazin (1840–1901) to Rodin, we know that, at Cazin’s suggestion, Legros and Ionides visited Rodin’s studio in Paris sometime in the early 1880s. Cazin had traveled to England in 1871, at which time he deepened his friendship with Legros before returning to France in 1875.[5] Though there is no date on the letter, we may presume that the Legros-Ionides visit to Rodin’s studio took place either at the end of 1880 or early in 1881, given that the earliest extant letter from Ionides to Rodin is dated June 22, 1881.

Legros and Cazin had studied together, along with Rodin, with the well- known art teacher Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran (1802–97) at the École Impériale Spéciale de Dessin et de Mathématique (known more commonly as the Petite École).[6] The painter Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904) and the sculptor Jules Dalou (1838–1902) were also among Lecoq’s students, and together the men formed a tightly knit group, encouraging each other’s artistic production and sharing their experience of art school. In addition to the young artists he became acquainted with at the Petite École, Legros, who had come to Paris from Dijon, also met James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), at whose suggestion he moved to England in 1863. In London, he became friendly with some of the Pre-Raphaelite painters, as well as with George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) and Frederic Leighton (1830–96). Until 1875, he occasionally sent works to the Paris Salon and, almost every year until 1882, he exhibited works at Royal Academy exhibitions. During 1876, he obtained a professorship at the Slade School of Fine Art, and in 1880, he became a naturalized British citizen.[7]

The banker Ionides mentioned in Cazin’s letter was Constantine Ionides (1830–1900), a Greek art collector who had been living in England since 1834. Constantine’s brother Alexander (known as Aleco) and Legros’s friend Whistler had met in the 1850s in the studio of Charles Gleyre (1807–74) in Paris; they met again in London in 1859, after Whistler had moved to England. Whistler introduced the Rossetti brothers and Edward Burne-Jones (1833–98) to the Ionideses, who were great patrons of Legros and other artists. Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–82), in turn, introduced Legros to Constantine Ionides, an event that would spark a close friendship between the two men.[8] In 1864 the Ionides family moved to Holland Park, not far from the center of London. From the beginning of the 1860s, this area attracted many newly wealthy industrialists, who competed to build the most fashionable mansions.[9] However, in 1868 Legros and Whistler had a falling-out; the father and the younger brother sided with Whistler, while Constantine stood alone with Legros.[10]

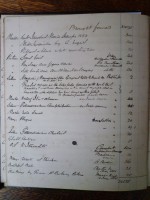

There is evidence that Constantine Ionides (referred to hereafter as Ionides) employed Legros as an advisor in his art collecting activities.[11] In a letter from Venice dated March 18, 1873 (fig. 4), Legros reported to Ionides that he had purchased a painting by Paolo Veronese (1528–88).[12] It would appear from their correspondence that Ionides had authorized Legros to buy any piece of art he considered worthy.[13] The Ionides Collection, bequeathed in 1901 to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, comprises 90 oil paintings, 750 prints, and 300 watercolors and drawings. Some are works by Legros himself, but most are by other artists, as the two men’s relationship was one of patron and artist, as well as collector and advisor.[14]

It is likely that Legros and Ionides visited Rodin’s studio while he was working on his monumental sculptural group, The Gates of Hell. Lucien Legros recorded his father’s impressions of The Thinker in his unpublished biography, noting that Legros “was struck by the meditative character of this figure and the ‘life’ in it.”[15] It is possible that the two men were present when the figure of The Thinker was raised to its position at the top of The Gates of Hell. A photograph of the salon in Ionides’s home (fig. 2) shows that the cast of The Thinker the collector would eventually acquire was placed high up, looking down upon the room, perhaps reflecting his memory of the visit to Rodin’s studio.

Some-time after this visit, Ionides agreed on a price for a sculpture in a letter to Rodin dated June 22, 1881 inquiring after the size of the piece in question.[16] When Rodin replied to Legros four months later, the artist referred to this sculpture as Two Infants Embracing, a work that is today known as Kissing Babes (fig. 5).[17] This was to be the first piece Ionides bought from Rodin; the initial step on his journey to becoming one of the sculptor’s most important collectors of the early 1880s.

Rodin traveled to England for the first time in July and August of 1881. During his stay, he was introduced by Legros to the art critic William Ernest Henley, who would become an important promoter of Rodin in Great Britain.[18] During his time in London, Rodin studied print techniques with Legros and left two drypoints, Love Conducting the World (fig. 6) and Figure Studies, which became part of the Ionides Collection.[19] After Rodin returned to France in August, Gustav Natorp (1824–91), Legros’s former student who would later become Rodin’s apprentice, took Legros’s statue known as Sailor’s Wife and his medal-making molds to Paris, where Rodin had them cast.[20] From mid-December, 1881, Legros spent a month in Paris,[21] during which time Rodin completed his Alphonse Legros, which he had started in England (fig. 7), and in turn Legros painted his Portrait of Rodin (fig. 8).[22]

Meanwhile, within Legros’s immediate circle, Rodin’s The Gates of Hell had begun to attract serious attention. In two letters dated April 22 and 24, 1882, Henley asked Rodin to bring sketches of it with him when he came to England.[23] Legros also continued to express interest in the project. In January 1883, he wrote about how Rodin’s students were keeping him updated on the door’s progress.[24] Later that same year, in March, Legros and Ionides made a return visit to Rodin’s studio in Paris,[25] and following his second visit to London that May, Rodin would send a photograph of Paolo and Francesca to Henley.[26]

Henley, together with a fellow editor of the Magazine of Art, William Cosmo Monkhouse (1840–1901), had reported on Rodin’s work in a series of articles published in the magazine from 1881 to 1884. During this time, hardly an issue went to print that did not contain an article relating to either Rodin, the Ionides Collection, or Legros.[27] Henley showed the photograph of Paolo and Francesca[28] to Ionides in November, and he immediately decided to obtain the “group.” This “group,” referred to in Henley’s letter to Rodin of November 20, 1883, was later cast in bronze at Ionides’s request.[29] A letter from Henley to Rodin dated December 7, 1883, stated:

Ionides has all this time been extremely happy with the group [The Kiss, previously known as Paolo and Francesca (fig. 9)]. I’ve been asked by Legros to tell you that you should ask Dalou’s opinion regarding its price. You should reconsider if Dalou, full of confidence in its success, suggests you charge a very high price. Once you’ve thought about it, lower the price to a level that you think is in the right range.[30]

Dalou, like Rodin and Legros, had studied in Lecoq’s studio. A radical republican, he was forced to go into exile in London after the crushing of the Paris Commune, and he returned to France only after the amnesty of 1879. While in London, he became very close to Legros who, in turn, introduced him to Ionides, who bought some of his works. At that time Legros must have thought that their mutual friend Dalou, in Paris, was sufficiently wise to the art market because he had sold his works following his success at the 1883 Paris salon.[31]

While Ionides obtained Paolo and Francesca, which had once occupied the left-hand panel of the Gates,[32] Henley’s article of the same year reported that Rodin remained hard at work on the massive bronze entrance, based on the theme of Dante’s Divine Comedy, and which was destined for the Museum of Decorative Arts.[33] In 1884, a year after he acquired The Kiss, Ionides went on to purchase The Thinker, a piece similarly conceived for The Gates of the Hell but which, together with other figures and groups for the door, was eventually sold as an independent work.[34] Ionides wrote, “Dante as Thinker, 160 pounds,” in his ledger in 1884 (fig. 10). Ionides purchased these two works in addition to the Kissing Babes, the Portrait of Legros, and the Man with a Broken Nose. Thus, by 1884, Ionides owned no less than five Rodin sculptures, more than any other collector.[35]

Exhibiting Rodin’s work in London

Rodin exhibited the Bust of Saint John the Baptist (fig. 11) at the Royal Academy in 1882. Writing to Rodin on May 6 of the same year, Legros expressed his concern that neither the bust, nor his own sculpture, Sailor’s Wife (fig. 12), were being shown to their best advantage by the Academy, and consequently were not attracting as much attention as he had hoped.[36] Legros’s fears were echoed in an article, likely written by Henley:

In our last illustration we give an engraving of what, all things considered, was certainly the best piece of sculpture in last year’s exhibition at the Royal Academy—the “St.-Jean” of M. Auguste Rodin. This statement may surprise, inasmuch as it is more than probable that most visitors never saw M. Rodin’s bust at all. It is badly placed in the background amidst a number of sugary nothings and lifeless ineptitudes, where the public never wander—where, too, that remarkable person the newspaper critic rarely ventures, and then only to disregard or to condemn. In short, it attracted little notice, least of all from the critics; and this is the more unaccountable because, in spite of being in a bad light, and at a scarcely proper distance from the ground, its union of vigour and dignity and intensity could not fail to fix the attention of any one who had eyes to see.[37]

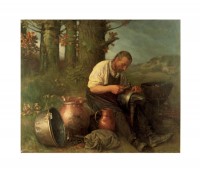

Following this report of less-than-ideal treatment of Rodin’s sculpture, Legros took it upon himself to display the work in his own studio following the Royal Academy’s exhibition. In September of the same year, in a letter to Rodin, Legros wrote encouragingly: “The Saint John is making a very beautiful impression in my studio. I have shown the Saint John to many people in the studio, and they praise it highly.”[38] Legros must have sympathized with his friend, because almost all of the works he himself had previously submitted to the Royal Academy had been poorly placed, displayed in locations where their full appreciation was impossible. Henley alluded in an 1880 edition of the University Magazine to the very poor conditions under which the Royal Academy had consistently exhibited Legros’s works, impeding public recognition of his talents. This treatment of Legros’s paintings had previously been noted in other journals; for example, in 1874 the Athenaeum magazine wrote about The Tinker (fig. 13), which was currently on show at the Royal Academy: “Ignorance of art and the man is the only honest apology they can offer for the ignominious place in which the hangers—let those by no means gentlemen divide the responsibility between them—have placed this fine work: above the line, not in a good light, and in a second-rate room.”[39] Similarly, the Art Journal complained that “no painter has been more unjustly dealt with by those entrusted with the disposition of the exhibited pictures than A. Legros. In the lecture-room a clever picture from his hand is hung close to the ceiling, and here Un Chaudronnier is put so far out of sight that its sterling merits are in danger of being overpassed.”[40] These quotations not only attest to Legros’s unfair treatment at the hands of the Royal Academy, but they also highlight the attitude of the academicians toward the revolutionary art that the artist and his friends were producing. It was not until 1877, when Sir Coutts Lindsay (1824–1913), owner of the Grosvenor Gallery, provided Legros with a suitable space in which to display his works, that his pieces could finally be appreciated.[41]

In view of his dissatisfaction with the Academy, it could have been Legros who proposed the Grosvenor Gallery to Rodin as an appropriate alternative in which to exhibit his sculptures. His friend Lindsay had opened this gallery to artists from all schools and displayed works by Edward Burne-Jones, James McNeill Whistler, and George Frederic Watts, artists who were not party to the Royal Academy’s exhibitions. Legros had shown his work at the Grosvenor Gallery from its inception, and he doggedly continued to submit works to the Royal Academy and probably advised Rodin to do the same and to also exhibit at the Grosvenor.

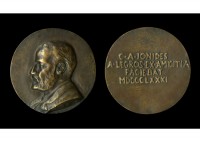

In 1882, Man with a Broken Nose and Alphonse Legros were displayed at the Grosvenor Gallery. Legros himself showed two sculptures and seven medals.[42] In a letter to Rodin dated August 18, Legros reported that Man With a Broken Nose (fig. 14) had been bought by Lord Frederic Leighton; that Alphonse Legros (fig. 7) had been obtained by Ionides; and that the Bust of Saint John the Baptist was now in Legros’s studio.[43] Some time later, although the specific date is unknown, Ionides purchased a cast of Man With a Broken Nose, and Rodin gave additional casts to Legros and Henley.[44] At the Grosvenor, Legros unveiled Death and the Woodcutter and Spring, two sculptures never before shown.[45] He also exhibited the seven medals mentioned previously, for the casting of which Legros had asked Rodin’s help.[46] One of these medals, a portrait of Ionides, was inscribed on the reverse: “C.A. Ionides A. Legros ex amicitia faciebat (made out of friendship) MDCCCLXXXI” (fig. 15). Legros penned a note to Rodin on January 7, 1883, expressing hope that his friend would consult him regarding the correct approach to take, if he thought it prudent to exhibit at the Grosvenor. In other words, Legros was willing to negotiate on Rodin’s behalf, using his personal contacts at the gallery.[47] Rodin went on to exhibit a full-body Saint John the Baptist (fig. 16) and five statues owned by Ionides at the Dudley Gallery, another new exhibition space founded to rival the Royal Academy.[48]

Henley wrote to Rodin on March 10, 1884, asking him to send forthwith the Age of Bronze (fig. 17) to London, intended for exhibition at the Royal Academy that same year:

With regard to the bust of Victor Hugo, I have made arrangements to return it to you through the good offices of Legros. Last Sunday morning I talked with Legros about this. By the same Legros I have been asked to send to you on his behalf his best regards of friendship, and to tell you that he is still anxious to receive your Age of Bronze. According to Legros (and I agree) you should as soon as possible send your Age of Bronze so that it can be kept for a little while by Legros in order to show it to artists and critics.[49]

As the letter shows, Legros intended to publicly display the Age of Bronze in his studio before having it shown at the Royal Academy, as confirmed by an undated letter from Legros to Rodin.[50] Legros and Rodin’s frequent correspondence, mediated by Henley, reveals it to be Legros who was responsible for the French sculptor’s works crossing the English Channel, for the purpose of exhibitions. Legros and Henley both believed it vital for Rodin’s works to be seen in London, in order that he might achieve worldwide renown. Writing on March 29, 1884, Legros made reference to the Age of Bronze, showing at the Slade School: “Your figure was a sensation . . . it is quite a beautiful piece. I find it as beautiful now as when I saw it for the first time and I hope it will bring you great success.”[51]

Sadly, Legros’s wish did not come true. When the Age of Bronze was finally unveiled at the Royal Academy, a disgruntled Henley noted that, once again, Rodin’s piece was unsatisfactorily positioned: “In the sculpture gallery, incomparably the best thing of all is M. Rodin’s Age of Bronze. It is badly placed; so that only one of its aspects is to be studied.”[52] The Academy’s public display of Rodin’s works was consistently dispiriting; the sales of his figures accomplished only through private galleries. Wherever possible, Legros—exhibiting his own sculptures and medals at the Royal Academy and the Grosvenor Gallery—shadowed Rodin and shared in both his disappointments and triumphs.

Taking on the Royal Academy

Despite a lack of encouragement from everyone except Legros, Rodin submitted his Idyll, completed in 1885, to the Royal Academy exhibition of the following year, but this time his work was rejected outright. The debate that erupted following this rejection held great meaning for relations between Legros’s cohorts and the establishment of the Royal Academy. Earlier studies have discussed this debate in detail, however it can summarized as follows: Léon Gauchez, writing under the penname of Paul Leroi in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, reported that the Academy’s jury had dismissed Rodin’s works. Upon reading this, Henley immediately translated Gauchez’s article into English and quoted him in the Magazine of Art, announcing his support for Rodin’s cause. Edward Armitage,[53] however, sided with the Academy, denouncing Rodin as “the Zola of sculpture” and severely criticizing his St. John the Baptist for its vulgarity. The controversy quickly escalated into an open public dispute in which Henley’s friends Robert Louis Stevenson and Sir Claude Phillips took Rodin’s side against the Academy.[54]

As we know, Legros’s friend Leighton, then president of the Royal Academy, had bought Man with a Broken Nose—shown at the Grosvenor Gallery—and put it on display at his home. A renowned painter, Leighton was also interested in sculpture and had himself cast a sculpture of a life-size male nude in 1877.[55] A new group of young British sculptors was rising to prominence in the 1880s. They shared Leighton’s artistic tendencies, and indeed, Leighton’s acquisition of Rodin’s sculpture during this period was the mark of active support for the revolution in sculptural styles taking place in Britain, predictably triggering opposition by British Academicians.[56]

Legros and Rodin’s personal struggle for recognition was a sign of the delicate complexities underlying Britain’s art world at the time. Legros strategically positioned himself on Rodin and Henley’s side with regard to the question of the Academy’s authority. Contrary to the Academy’s intentions, however, the resulting public controversy was for Legros and the others a superb opportunity to spotlight the British Academy’s prejudice against new art from France, and brought Rodin international attention.

Legros’s Motivations for Assisting Rodin

Legros’s efforts to popularize Rodin’s works in England were not simply an attempt to rile the Academy out of personal spite, but rather for the more selfless act of promoting contemporary French art in Great Britain based on his admiration for Rodin as an artist.

Legros, Ionides, and Henley sought to raise the profile not only of Rodin, but of all contemporary French art, and to bring this art not just to a small elite circle but to the general public. The three men, united in this common purpose, turned their attentions to suitable teaching methods.

Legros intended to export the method of drawing he learned in France. Accordingly, in the early 1870s—in collaboration with Dalou and Cazin, his former classmates at the Lecoq studio—he founded Britain’s first school of art to have put into practice a French teaching methodology.[57] The school employed the drawing techniques originally taught by Lecoq de Boisbaudran in his studio, a practice that underpinned Legros’s work throughout his career. Lecoq emphasized in his book L’Éducation de la Mémoire Pittoresque et la Formation de l’Artiste the importance of a grounding in “Memory Drawing,” which visualized images from the memory, because this training not only improved the techniques of drawing, but also raised the creative power of the artist.[58] In the foreword to Lecoq’s book, which Rodin wrote for his professor, he testified that this training had meant everything to him and to Legros.[59]

As we know, in 1876 Legros was named professor at the Slade School; his role there was to instigate art education à la française, as has been discussed previously.[60] In a letter dated March 29, 1884, Legros told Rodin that his Age of Bronze had excited viewers greatly during its time at his school before its eventual transferal to the Royal Academy.[61] That Legros presented the Age of Bronze to his students at the Slade, where the emphasis was on drawing the human form, is testimony to Legros’s confidence in his fellow artist’s embodiment of Realism. Legros would go on to send several of his students, including Gustav Natorp and Marie Cassavetti Zambaco, to Rodin in Paris for training.[62]

The critic Henley was also among those who, refusing to accept the Royal Academy’s pedagogical orthodoxy, was active in spreading the gospel of contemporary French art throughout Britain. Henley organized an International Exhibition in Edinburgh in 1886, borrowing from the Ionides Collection paintings by Legros and his friends, as well as painters of the Barbizon School. The catalogue states clearly that the exhibition’s main purpose was “a protest against much of the art-teaching of the present day.”[63] Henley held another exhibition two years later, this time in Glasgow, where he showed The Idyll, the piece which had so famously been rejected by the Royal Academy, as well as four other works by Rodin, including Rodin’s statue of him.[64]

When Constantine Ionides died in 1900, he bequeathed all his paintings, prints, and drawings to the Victoria and Albert Museum, specifying in his will that they were to be made available to the public and that it was the responsibility of the museum to ensure the prints and drawings were readily accessible to students.[65] Thus, Legros, Henley, and Ionides sought to reveal art’s social significance and to insist, by displaying works in art schools, museums, and at exhibitions, that the French art of their period, based on the artistic methods that Legros and his friends shared, would become well known in English society. This translated the political ideals of republicanism into education for the masses, and helped to popularize the French republican policies of the political leader Léon Gambetta.[66]

Before Legros’s promotion of Rodin, he had already introduced to Ionides his old friends from Lecoq’s studio, Guillaume Régamey (1837–75) and Léon-Augustin Lhermitte (1844–1925) who avoided the turbulent political situation in France after the Franco Prussian War and went to London, and Dalou who sought political asylum there in 1871 after the fall of the Commune, which he had supported.[67] Ionides would go on to purchase works from all three men over the next ten years.[68] A consistent leitmotif in these works by Legros and his friends was the image of the common laborer and of peasants working in the fields. The figure in Legros’s Tinker (fig. 13) is depicted at work by the side of a country road, and in Régamey’s A Team of Percheron Horses (1870) both man and beast come to symbolize rural Normandy. Similarly, Lhermitte painted mostly peasants in the market and at the Pardons festival in Brittany. Dalou’s sculpture of A French Peasant Woman (1873) and Millet’s Wood Sawyers (1850–52) are listed in the Ionides collection, in whose pervasive French regionalism a notable political coloring is detectable.[69]

Background Republicanism: Legros’s Alternative Motivation

Although Legros’s artistic circle was not named as a group of artists in the context of modern art history, alumni of Lecoq’s studio were meeting at the Café Américain in Paris while Rodin’s works were being exhibited in London in the early 1880s. This group included Rodin, Dalou, Lhermitte, Jean-Paul Laurens (1838–1921), Cazin, Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848–84), and, significantly, Legros and Henley. Later, Rodin and some of his contemporaries withdrew from the Société des Artistes Français and became instead core members of the independent Société Nationale des Beaux- Arts (National Society of Fine Arts).[70]

Meanwhile, over in England, well-heeled intellectuals and politically left-leaning Liberal Party members of Parliament, such as Legros’s patrons Charles Dilke (1843–1911) and Thomas Eustace Smith (1831–1903), and Legros’s student George Howard, 9th Earl of Carlisle (1843–1911), were buying up Legros’s works.[71] Dilke in particular, who was known to be a supporter of French republicanism, commissioned a portrait in 1875 from Legros of their much-admired friend, Gambetta (fig. 18).[72] Ionides was himself a friend of the Liberal Party leader and later prime minister William Gladstone (1809–98), whose right-hand man was the aforementioned Dilke; Legros even cast a Gladstone medal.[73]

Legros acted throughout his life as an intermediary, supporting artists with republican tendencies and introducing them into influential circles of patronage, as he would do with Rodin and Ionides. A Republican majority in the French parliament in the early 1880s, and the subsequent support of this political sphere, led to social success for Rodin, Dalou, Cazin, Lhermitte, and many other artists. During this period, their friend and leader of the French republican government, Gambetta, was elected prime minister of the Third Republic and set about transforming the government’s art policies during his short time in office, which lasted from November 1881 to February of the following year.[74] Legros enjoyed a close relationship with Gambetta prior to his move to England.[75]

As part of the art-policy reform, Gambetta established the Ministry of Culture, an independent government agency for arts administration, naming Antonin Proust, who was close to Edouard Manet, as the first minister of culture.[76] At the 1878 Paris World Fair, Gambetta became apprehensive about the level of French decorative arts falling behind that of England, and in order to advance artistic education that responded to industrialization under the new ministry, he created a plan for the widespread dissemination of drawing and design education.[77] The Museum of Decorative Arts was planned in line with Gambetta’s policies, and Rodin received the commission through the office of Edmond Turquet, then under-secretary of state in the Ministry of Fine Arts, to create its doors.[78] Thus, Rodin created The Gates of Hell, and Ionides, through the offices of Legros, purchased the Thinker.

Conclusion

The following letter summarizes the respect Legros had for Rodin as an artist. Having revisited Rodin’s studio in 1886, he wrote to Ionides: “I have just returned from Paris where I could look at the beautiful works by Rodin. There is at least one who could say with justice and pride ‘I was raised to a higher level.’”[79] This reverence for Rodin’s artistic vision was what inspired Legros’s determined promotion, until his death, of the artist’s works.[80] Ultimately, Legros’s passion for art education and his efforts to introduce modern French art to the people of Great Britain resonated with Ionides and Henley. Through Legros, a deliberate mediation network of artists, collectors, and critics took shape, whose collaboration would lead to the eventual popularization of Rodin’s works overseas.

Owing much to the strategic promotional activities of Legros and his circle, England’s receptiveness to Rodin’s works found expression not only in the love of art practiced by those men close to Legros, but also through increasing challenges to the Royal Academy’s rigidity. It is important to remember that Legros’s efforts to introduce French artists to Great Britain were not limited to Rodin but rather extended to his classmates from Lecoq de Boisbaudran’s studio, who all shared his artistic and political ideals. Gambetta’s policies facilitated Rodin’s commission of The Gates of Hell. Parts of the doors were completed as sculptures, carried to England and, together with other works by Rodin, advertised by his acquaintances in the print media and purchased by Legros’s friends in England. This process—an example of cultural transmission whereby information was spread via the printed page from France to England, and from administrative levels to the general public—was forged by the complex network of artists and supporters around Legros, based on French republicanism, that spanned England and France, and it confirms a chain of artistic activity in which Legros played a most significant role.

All translations are by the author.

I am deeply grateful to Professor Atsushi Miura of the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, who has guided my research throughout. I remain indebted to the late Julia Ionides, descendant of Constantine Ionides, Catherine Chevillot, Directrice of Musée Rodin, Sandra Boujot, archivist at the Musée Rodin, and Philip Attwood, Keeper and Head of Department of Commemorative and Arts Medals at the British Museum. I extend special thanks to Laura Mayer for her editing and encouragement, as well as to Petra Chu, Robert Alvin Adler, and Isabel Taube for their contributions. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Number JP15K02146.

[1] “Art Notes,” Magazine of Art 5 (1882): viiii. This article could have been written by Henley, but no specific author is mentioned in the original text.

[2] For the reception of Rodin’s works in England, see the following: Catherine Lampert and others, Rodin, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2006); Andrew Watson, “Constantine Alexander Ionides: Rodin’s First Important English Patron,” Sculpture Journal 16, no. 2 (2007): 23–38; Claudine Mitchell, ed., Rodin, the Zola of Sculpture (Vermont: Ashgate, 2004); and Ruth Butler, Rodin: The Shape of Genius (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993), 163–78.

[3] On the relationship between Constantine Ionides and Legros, see the following: Andrew Watson, “The Collection of Constantine Alexander Ionides (1833–1900): With Special Reference to the French Nineteenth-Century Paintings, Etchings, and Sculptures,” (PhD diss., University of Aberdeen, 2002); Timothy Wilcox, “The Art Treasures of Constantine Ionides, Hove’s Greatest Collector,” Hove Museum and Gallery Catalogue (Brighton: Hove Museum and Art Gallery, 1992); and A. Leoussi, “The Ionides Circle and Art,” (M. Phil. thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 1982).

[4] Cazin to Rodin, undated, CAZ1193, Rodin Museum Archives, Paris (hereafter, RMA). This English translation is quoted in Watson, “Rodin’s First Important English Patron,” 34.

[5] Léonce Bénédite, Jean-Charles Cazin, Les Artistes de Tous Les Temps, Série D, Le XXe Siècle (Paris: Librairie de L’Art Ancien et Moderne, 1902), 17, 19–21.

[6] Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran, L’Éducation de la Mémoire Pittoresque et la Formation de l’Artiste (Paris: Henri Laurens, 1920?). Lecoq, famous for his teaching method based on visual memory training, reproduced at the end of his book (plate no. 5) Legros’s copy, from memory, of the Portrait of Erasmus by Hans Holbein at the Louvre.

[7] On Legros’s life, see the following: Alexander Seltzer, “Alphonse Legros, The Development of an Archaic Visual Vocabulary in Nineteenth Century Art,” (PhD diss., University of New York at Binghamton, 1980); Timothy Wilcox, “Alphonse Legros (1837–1911): Aspects of his Life and Works,” (M. Phil. thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 1981); Timothy Wilcox, Alphonse Legros, exh. cat. (Dijon: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, 1987); and Lucien Alphonse Legros and Harold Wright, “An Incomplete Draft of the Biography of Alphonse Legros,” GB247 MS, Wright L445, p. 38, Glasgow University Library Special Collections, Glasgow.

[8] Watson, “Rodin’s First Important English Patron,” 23–38; Mitchell, Rodin, the Zola of Sculpture; Butler, Shape of Genius, 163–78; and Legros and Wright, “Biography of Alphonse Legros,” 38.

[9] For the circle of artists supported by the Ionides family and other wealthy new industrialists, see Caroline Dakers, The Holland Park Circle: Artists and Victorian Society (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999).

[10] Wilcox, Alphonse Legros, 72; and Luke Ionides, Memories (Ludlow, 1996), 13. This is a facsimile reprint published with an afterword by J. Ionides. The original text was published in Paris in 1925.

[11] Legros and Wright, “Biography of Alphonse Legros,” 43; and Alexander C. Ionides, Jr., Iõn: A Grandfather’s Tale (Dublin: Cuala Press), 8–10.

[12] Currently, this work, attributed to Benedetto Caliari, is in the Ionides Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

[13] “Il y a deux tableaux de Paul Veronèse chez M. Marcats. On en demande cent livres. Je trouve que c’est une bonne occasion. Je vous en préviens. Tout ce que j’ai à vous dire c’est que les tableaux sont de Veronèse et que si j’étais plus riche je les prendrais pour moi. . . . Je vous donne de l’autre côté de la page la forme des deux peintures. C’est la seule occasion que j’ai trouvé pendant mon voyage. Quoique vous m’ayez donné carte blanche je préfère pourtant vous prévenir.” Legros to Ionides, March 18, 1873, collection of the late Julia Ionides, Ludlow, England (hereafter, CJIL).

[14] Legros’s work consists of 3 oil paintings, 2 watercolor landscapes, 132 etchings, and 54 drawings.

[15] Legros and Wright, “Biography of Alphonse Legros,” 179–80.

[16] Ionides to Rodin, June 22, 1881, ION.3261, RMA.

[17] This work is referred to as “the group of two children” (le groupe des deux enfants) in a letter from Legros to Rodin dated October 19, 1881, LEG.3769, RMA: “Ionides me demande quand vous aurez terminé le groupe des deux enfants, le temps lui dure de la mettre à la place qu’il lui réserve.” (“Ionides asks when you will have finished the group of two children; he’s impatient to put it in the place he has reserved for it.”) In Ionides’s ledger, it is listed simply as “Le Groupe.” Inventory Book of C. Ionides, CJIL. This statue has been identified as the Kissing Babes, cast in 1881, and which later belonged to Ionides. Lampert and others, Rodin, 211. The prior acquisitions of a Rodin in England were “a statuette Rose,” purchased by E. F. Tuckette and “two of Rodin’s decorative busts, one ornamented with roses, the other with grape leaves” purchased by Ernest Motte. Tahinci, “Private Patronage,” 95, and, generally, for buyers of Rodin’s works, 95–117.

[18] For Henley having met Rodin through Legros, see Joy Newton “William Ernest Henley and the Launching of Rodin’s Career,” in Mitchell, Rodin, the Zola of Sculpture, 60. Henley had already written an article about Legros in the University Magazine in 1880, in which he described the circumstances of Legros’s meeting with both Jules François Félix Fleury-Husson (1820–89), better known as Champfleury, and Léon Gambetta (1838–82), the politician and symbolic figure of French republicanism. In this article he also discussed the progress of some paintings Legros was working on at the time. From this article, which contains information that only Legros could have provided, we can surmise that Henley and Legros were already on familiar terms with each other in the 1880s. William Ernest Henley, “M. Alphonse Legros,” University Magazine, February 1880, 198–206.

[19] Catherine Lampert, Rodin, Sculpture & Drawings, exh. cat. (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1986), 201–2; and Catherine Lampert, Rodin, Sculpture & Drawings, exh. cat. (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1970), 115. According to the 1970 catalogue, Rodin’s Love Conducting the World is engraved on the reverse of Legros’s copperplate print, Study of a Young Person’s Head.

[20] See letters from Legros to Rodin dated October 30, 1881, and December 7, 1881, LEG.3769, RMA; and Philip Attwood, “The Medals of Alphonse Legros,” The Medal 5 (September 1984): 7–24.

[21] Rodin to Maurice Haquette, mid-December 1881, in Auguste Rodin, Correspondance de Rodin I, 1860–1899, Textes classés et annotés par Alain Beausire et Hélène Pinet (Paris: Musée Rodin, 1985), 54.

[22] Even before 1880, Legros was working on a portrait of Rodin in drypoint. On the statue of Rodin being made at this time, see Butler, Shape of Genius, 163–78.

[23] Henley to Rodin, April 22, 1882, HEN.3036, RMA: “Et quant à la place de la grande porte, je crois que le mieux sera d’attendre jusqu’à [ce que] nous en puissions parler ensemble. En venant en Angleterre, vous emporterez vos dessins; nous en causerons; et la chose sera faite”; and Henley to Rodin, April 24, 1882, HEN.3036, RMA: “J’aurais bien voulu voir pour moi-même les dessins pour la grande porte; Legros m’en a dit des merveilles, et j’ai été vraiment fâché de savoir que vous ne pouviez pas me les confier.”

[24] Legros to Rodin, January 7, 1883, LEG.3769, RMA.

[25] Ionides to Rodin, March 8, 1883, ION.3261, RMA.

[26] Henley to Rodin, September 27, 1882, HEN.3036, RMA.

[27] Henley, “M. Alphonse Legros,” 198–206; William Ernest Henley, “Alphonse Legros,” Art Journal, n.s. (1881), 94–296; Cosmo Monkhouse, “Professor Legros,” Magazine of Art 5 (1882): 327–34; William Ernest Henley, “Current Art,” Magazine of Art 6 (1883): 175–76, 431–32; Cosmo Monkhouse, “The Constantine Ionides Collection,” Magazine of Art 7 (1884): 36–44, 120–127, 208–14; William Ernest Henley, “Two Busts of Victor Hugo,” Magazine of Art 7 (1884): 128- 132; William Ernest Henley, “Current Art,” Magazine of Art 7 (1884): 347–52, 392–96; William Ernest Henley, “Medals of the Stage,” Magazine of Art 9 (1886): 524–28; William Ernest Henley, “The Academy and Rodin,” Magazine of Art 9 (1886): 394–95; Cosmo Monkhouse, “Auguste Rodin,” Portfolio 18 (1887): 7–12; and William Ernest Henley, “Modern Men, Auguste Rodin,” Scots Observer (Edinburgh), May 10, 1890, 682–83.

[28] This statue, originally titled Paolo and Francesca, formed part of the Gates of Hell; it was later renamed The Kiss. Lampert and others, Rodin, 79.

[29] Henley to Rodin, November 20, 1883, HEN. 3036, RMA: “C’est celle-là où je vous dis, de part Ionides, que vous ferez bien de faire fondre une épreuve en bronze du Paolo et Francesca pour la collection que vous connaissez.”

[30] “Ionides est toujours enchanté du groupe. Legros me charge de vous dire que, pour ce qui rapporte au prix, vous devez demander des conseils à Dalou. Si Dalou, gonflé de succès, vous conseille de demander de fortes sommes, vous réfléchirez; après avoir réfléchi, vous en rabattrez tant que vous croirez juste.” Henley to Rodin, December 7, 1883, HEN.3036, RMA.

[31] Amélier Simier, assisted by Marine Kisiel, Jules Dalou, le sculpteur de la République: Catalogue des sculptures de Jules Dalou conservées au Petit Palais (Paris: Petit Palais, 2013), 16, 58.

[32] Lampert and others, Rodin, 79.

[33] Henley, “Current Art,” Magazine of Art 6 (1883): 176.

[34] For the first published source of commentary on the doors see ibid. Henley’s friend Cosmo Monkhouse, co-editor of the Magazine of Art, described both doors as a single unit expressing the theme of the Inferno in Dante’s Divine Comedy, suggesting that Rodin had carried out a change from his original design in the 1880s. See Monkhouse, “Auguste Rodin,” 7–12. This article by Monkhouse is the first study in English to comprehensively discuss Les Portes de l’enfer, according to Mitchell, Rodin, the Zola of Sculpture, 24–29.

[35] Tahinci, “Private Patronage,” 95–117.

[36] “Le Saint Jean, à l’académie, n’est pas trop bien placé, mais on le voit pourtant, du reste vous partagez là le sort de beaucoup d’autres, moi compris.” Legros to Rodin, May 6, 1882, LEG.3769, RMA.

[37] “Current Art,” Magazine of Art 6 (1883), 175–76.

[38] “Le St. Jean faisait fort bel effet dans mon atelier où je l’ai fait voir à beaucoup de monde c’est à dire qu’il a été beaucoup admiré.” Legros to Rodin, September 29, 1882, LEG.3769, RMA.

[39] “The Royal Academy,” Athenaeum 2428 (1874): 638.

[40] Art-Journal, n.s. 13 (London: 1874), 162.

[41] Henley, “M. Alphonse Legros,” 201–3.

[42] For exhibitions of Rodin’s works in England, see the 2006 Rodin exhibition catalogue, Lampert and others, Rodin; and Rodin, Correspondance de Rodin. For the Grosvenor Gallery exhibitions, see Christopher Newall, The Grosvenor Gallery Exhibitions: Change and Continuity in the Victorian Art World (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 96.

[43] Legros to Rodin, August 18, 1882, LEG.3769, RMA: “J’ai fait retirer vos choses des expositions. Le masque a été remis à Sir Fred. Leighton et le buste (mon portrait) à M. Ionides. Quant à votre St. Jean, il est dans mon atelier.”

[44] Tahinci, “Private Patronage,” table 5.1.

[45] Newall, Grosvenor Gallery Exhibitions, 96.

[46] “Merci ami pour vous être occupé de ces petites médailles.” Legros to Rodin, November 23, 1881, LEG.3769, RMA. “Voudriez vous me donner l’adresse de votre fondeur ou de celui que vous croiriez pouvoir me recommander pour mon groupe.” Legros to Rodin, December 7, 1881, LEG.3769, RMA.

[47] “Si vous croyez utile d’exposer au Grosvenor vous m’arrangerez la chose de façon à ce que je puisse prendre mes mesures en conséquence, c’est-à-dire, en parler aux autorités de l’endroit.” Legros to Rodin, January 7, 1883, LEG.3769, RMA.

[48] Alain Beausire, Quand Rodin Exposait (Paris: Musée Rodin, 1988), 86.

[49] “Et quant au buste d’Hugo, j’ai arrangé qu’il vous soit remis par voie de Legros, à qui j’en ai parlé hier (dimanche) matin. Ce même Legros me charge de vous donner, de sa part, toutes les amitiés du monde, et de vous dire qu’il attend toujours votre Age d’Airain. Selon lui—et selon moi aussi—vous devez le faire partir au plutôt possible, afin qu’il le tienne un peu chez lui, pour le montrer aux artistes et critiques.” Henley to Rodin, March 10, 1884, HEN.3036, RMA. Legros first mentioned the bust of Hugo when he wrote to Rodin on January 7, 1883, LEG.3769, RMA: “Le buste de Hugo fait un très bel effet, mais je préfère celui de Jean Paul Laurens et le mien, c’est-à-dire, celui que vous avez fait de moi.” (The bust of Hugo created a very beautiful effect, but I prefer the bust of Jean Paul Laurens and mine, that is to say, the one you had made of me.) It was exhibited to the public in the Institute of Painters in Oil in February 1884. Beausire, Quand Rodin Exposait, 89.

[50] Legros to Rodin, undated, LEG.3769, RMA: “Je crois qu’il serait bon que vous envoyiez votre figure, le plus tôt possible, pour que je puisse l’exposer dans mon atelier avant de le placer à l’académie.”

[51] “Votre figure a fait sensation dans l’école, c’est une bien belle oeuvre. Je la trouve aussi belle aujourd’hui que la première fois que je l’ai vue et j’espère un grand succès pour vous.” Legros to Rodin, March 29, 1884, LEG.3769, RMA.

[52] Henley, “Current Art,” Magazine of Art 7 (1884): 351.

[53] Edward Armitage (1817–96) was a history painter who had trained in the studio of Paul Delaroche at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and served as professor at the Royal Academy (1875–82). He continuously exhibited his pictures at the Royal Academy from 1848 to 1893. Robyn Asleson, “Edward Armitage” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 2:399–400.

[54] Read, “Royal Academy and the Rodin Problem,” 45–49; and Antoinette Le Normand- Romain, “The Greatest of Living Sculptors,” in Lampert and others, Rodin, 35–37.

[55] Read, “Royal Academy and the Rodin Problem,” 53.

[56] Ibid., 45–57.

[57] Letter from Cazin to the Mayor of Tours, November 2, 1871, quoted in “Jean-Charles Cazin et Alphonse Legros,” Touraine républicaine, May 1, 1922.

[58] Lecoq, L’Éducation de la Mémoire, 21–42; and Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, “Lecoq de Boisbaudran and Memory Drawing: A Teaching Course between Idealism and Naturalism,” in The European Realist Tradition, ed. Gabriel P. Weisberg (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982).

[59] Lecoq, L’Éducation de la Mémoire, 1.

[60] Stuart Macdonald, The History and Philosophy of Art Education (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 2004), 269–83.

[61] Legros to Rodin, March 29, 1884, LEG.3769, RMA.

[62] Lampert and others, Rodin, 291–92, 294.

[63] William Ernest Henley, Memorial catalogue of the French and Dutch loan collection, Edinburgh International Exhibition, 1886 (Edinburgh: Douglas, 1888), xxxvii.

[64] Joy Newton, “William Ernest Henley and the Launching of Rodin’s Career” in Mitchell, Rodin, the Zola of Sculpture, 66.

[65] Basil S. Long, Catalogue of the Constantine Alexander Ionides Collection, vol. 1, Paintings in Oil, Tempera and Water-Colour, Together with Certain of the Drawings (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1925), iv.

[66] Patricia Mainardi, The End of the Salon: Art and the State in the Early Third Republic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 65–66.

[67] Dalou remained in London from 1871 until 1879, when the amnesty of the French government permitted him to return to France. Simier, Jules Dalou, 16. Régamey and Lhermitte returned in 1871, after which Ionides visited them in their Parisian studios to commission paintings. Andrew Watson, “The Collection of Constantine Alexander Ionides (1833–1900): With Special Reference to the French Nineteenth-Century Paintings, Etchings, and Sculptures” (PhD diss., University of Aberdeen, 2002).

[68] According to Long, Catalogue of the Constantine Alexander Ionides Collection, 31–34, 38, 49–51, and the website of the Victoria and Albert Museum, V&A, “Search the Collections,” http://collections.vam.ac.uk/, last updated August 5, 2016, accessed August 31, 2013, there are, in total, 88 oil paintings in the Ionides Collection; 36 French paintings including 12 paintings by alumni of Lecoq’s studio (3 Legros, 3 Régamey, 2 Lhermitte, 3 Henri Fantin-Latour, 1 George Bellenger) and 17 English paintings including 11 family portraits by Frederic Watts. In addition Ionides bought four sculptures by Dalou. He also helped Lhermitte to sell his works in England. See Lhermitte to Ionides, May 4, 1877, CJIL.

[69] It is recorded that Legros recommended the acquisition of Millet’s Wood Sawyers to Ionides. See Legros and Wright, “Biography of Alphonse Legros,” 43. In relation to the same work, see also Bruce Laughton and Lucia Scalisi, “Millet’s Wood Sawyers and La République Rediscovered,” Burlington Magazine 134, no. 1066 (January 1992): 12–19.

[70] Butler, Shape of Genius, 168–69. For information on artists’ groupings, see Jean-Paul Bouillon, “Société d’artistes et institutions officielles dans la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle,” Romantisme 16, no. 54 (1986): 89–113.

[71] Paul-Emmanuel-Auguste Poulet-Malassis, M. Alphonse Legros au Salon de 1875 (Paris: P. Rouquette, 1875); Timothy Wilcox, “The Aesthete Expunged: The Career and Collection of T. Eustace Smith, MP,” Journal of the History of Collections 5, no. 1 (1993): 43–57; and Catalogue of Choice, Modern Etchings and Drawings, excluding the properties of the late Rosalind Countess of Carlisle (London: Sotheby, 1922), 9–11.

[72] “Now, here is the reason why I went to Paris. I was tasked by sir Charles Dilke to paint the portrait of my friend Gambetta so, naturally, I had to spend some time with my model.” (“Voici maintenant pourquoi je suis allé à Paris. J’ai été chargé par sir Charles Dilke de faire le portrait de mon ami Gambetta et j’avais besoin, naturellement, de passer quelque temps avec mon modèle.”). Legros to Michel-Hilaire Clément-Janin, April 17, 1875, quoted in Noël Clément-Janin, “Alphonse Legros et Dijon,” Revue de Bourgogne 3 (1913), 145; Henley, “M. Alphonse Legros,” 200; Tomoko Ando, “Alphonse Legros and Charles Dilke: Republicanism in England Reflected in ‘Portrait of Leon Gambetta,’” Interdisciplinary Cultural Studies 16 (2011): 87–105 [アルフォンス・ルグロとイギリスの共和主義者、チャールズ・ディルク : 《レオン・ガンベッタの肖像》をめぐって] (超域文化科学紀要 16).

[73] Ionides, Memories, 43.

[74] Jean-Marie Mayeur, Léon Gambetta: La Patrie et la République (Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard, 2008), 371–432.

[75] Paul-Emmanuel-Auguste Poulet Malassis, M. Alphonse Legros au Salon de 1875, note critique et biographique (Paris: P. Rouquette, 1875), 10; Henley, “M. Alphonse Legros,” 200; and Legros and Wright, “Biography of Alphonse Legros,” 88.

[76] Véronique Prest, “Antoine Proust, Ministre des Arts: Une politique, une esthétique” (Paris: Université Paris X Nanterre, Mémoire de Maîtrise Histoire de l’Art, 1983/1984), 63.

[77] Mainardi, End of the Salon, 65–66.

[78] Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, “The Gates of Hell: The Crucible,” in Lampert and others, Rodin, 55.

[79] “Je suis juste de retour de Paris ou j’ai vu les beaux travaux de Rodin. En voilà un au moins qui pourrait dire avec justesse et orgueil ‘je me suis élevé.’” Legros to Constantine Ionides, January 14, 1886, CJIL.

[80] In 1902, Legros was one of the initiators of a public campaign to raise money to permit Rodin’s Saint John the Baptist to be acquired and put in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Rodin, Legros, and Henley attended a party to celebrate the campaign’s success. Antoinette Le Normand-Romain, “When I Consider the Honours that Have Been Bestowed upon Me in England,” in Lampert and others, Rodin, 125; and Joy Newton, “William Ernest Henley and the Launching of Rodin’s Career” in Mitchell, Rodin, the Zola of Sculpture, 67.