The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Salazar: Portraits of Influence in Spanish New Orleans, 1785–1802

Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans

March 8–September 2, 2018

Catalogue:

Cybèle Gontar, ed.,

Salazar: Portraits of Influence in Spanish New Orleans, 1785–1802.

New Orleans: University of New Orleans Press, 2018.

240 pp.; 273 color illus.; bibliography, index.

$65.00 (hard cover)

ISBN: 9781608011544

The exhibition Salazar: Portraits of Influence in Spanish New Orleans, 1785–1802 was as rich in its display of material culture and archival documentation as it was ambitious in its treatment of a cross-border, multicultural topic (fig. 1).[1] Organized to coincide with the 300th anniversary of the founding of the city of New Orleans by the French crown, the exhibition offered a monographic study of the portrait artist Josef Francisco Xavier de Salazar y Mendoza (ca. 1750–1802). Born in Mérida, Yucatán, Mexico, Salazar emigrated to Spanish-ruled New Orleans in 1784, becoming one of the most renowned and successful artists in the city. His work captured the New Orleans high society of the late eighteenth century, when the city was administered by Spanish rulers. The exhibition also includes a selection of portraits made by later New Orleans artists from the Ogden Museum’s collection as a coda to this homage to Salazar.

In response to the question, “Salazar, Why Now?,” guest curator Cybèle Gontar replies that the exhibition “helps to broaden our perspective on what we deem Southern art” (9). This is the conclusion of her first essay in the exhibition catalogue, where she discusses the urgency of studying the portraits as “a material fragment of a past community—internationally diverse, yet closely networked,” within the frame of New Southern studies (9). This field has emerged from the recent shift toward a multicultural paradigm in American art history. New Southern studies seeks to remap the history of American art’s bias for Anglo-American and Eastern Seaboard culture. According to Gontar, “New Southern studies insists that regionally and culturally the South has never stood alone; it must be reexamined in a postcolonial context, especially considering its intrinsic ties with the Caribbean and Central and South America” (10). Salazar presents a fascinating case study because of his engagement in the circum-Atlantic world reaching the West Indies, Mexico, Central America, Spain, and France.

The first gallery of the exhibition welcomed visitors with an impressive array of diverse materials (fig. 2). There were maps, portraits, archival records, casta or breed paintings, and even a so-called “ormolu clock,” meaning a gilded clock. The purpose of this room was to situate the visitor in Salazar’s time in Louisiana. The text panel informed visitors of Spain’s acquisition of Louisiana in 1762, with the Treaty of Fontainebleau, and the grant of the territory of the western Mississippi River Valley in 1763, with the Treaty of Paris. A turbulent period followed in which the Spanish authorities struggled to control the Louisiana colony, which was mainly populated by French Creoles, Indians, and African slaves. The colony was both rebellious and a financial drain to the Spanish administration. It was governor Alejandro O’Reilly and later Bernardo de Gálvez who imposed Spanish rule and set a program of measures to rationalize the colony and make it financially sustainable. One of these measures was to welcome foreigners with contracts and land grants. Salazar emigrated to New Orleans in this period of mass migration to the city.

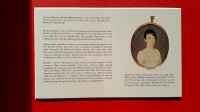

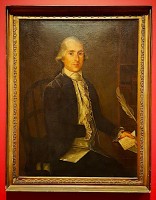

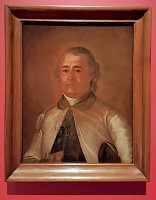

The displays in the first gallery, because of their seeming function to provide broad context, should be read as historical documents. The first map to the left, made in 1774 for British army officers, shows the Spanish North American territories and their links to the Caribbean and New Spain at the time. The two portraits to the right of the text panel feature Salazar’s likeness of the Spanish Missouri Surveyor and later army commander, Martín Milony Duralde, and that of Governor William Charles Cole Claiborne, by an unidentified artist, from around 1810 (fig. 3). Claiborne served as Louisiana’s first non-colonial governor of the Territory of Orleans from 1804 to 1812. Worth noticing is the caption label for Milony Duralde’s portrait, which reproduces a miniature portrait of his wife owned by The Historic New Orleans Collection, which expresses the desire by the curator to reveal the social and institutional ties among the subjects represented in the exhibition (fig. 4). Opposite the entrance hung an enlarged reproduction of the casta/breed painting De albina y español, nace torna atrás (From an Albino Woman and a Spaniard, a Return-backwards Is Born), used to exemplify how a portrait studio worked in colonial Mexico (see fig. 2). In the image, the artist is painting a portrait of his wife, who is sitting to the left of the painting, the son of the artist is handling an engraving, while a fourth person is cleaning an engraving plate.

The other side of the room introduced Salazar’s Mérida, Yucatán, and New Orleans (fig. 5). The text panel related the family’s connection to the Cathedral of San Ildefonso in Mérida, a religious building that held a significant art collection originally from Spain (likely brought by one of the cathedral’s archbishops). This collection might have inspired the young artist to pursue painting as a career. In addition to this early stimulus, Salazar certainly received training in the Yucatán area, as the text panel revealed that he used a red ground layer, like the other painters of the area did at the time. Next to the text appeared a map of the Gulf of Mexico (1707), and a map of Louisiana that included a plan of the city of New Orleans (1762). The pastel portrait of Francisco Domingo Joseph Bouligny, Spanish surveyor and strategist in the colonial army, completed the wall display. The center of the room presented two cases containing ledgers and a clock. One ledger registered the census of New Orleans from 1791, which shows that Salazar was recorded in it as a painter. The other ledger is an inventory of the artist’s belongings at the time of his death in August 1802. The ormolu clock referred to the one listed in the inventory and served not only as an illustration of the object Salazar possessed but also offered a glimpse into his daily material world.

The next gallery began by addressing Salazar’s portraits proper (fig. 6). The text panel described his artistic production in terms of New Spanish portraits due to his incorporation of naïve painting qualities, formal poses, and cartouches to add text. Characteristic of Salazar’s work are the aforementioned red ground layer, the framing of the subject with an oval device, and the addition of props and letters that the subject handles. The map of New Orleans, made in December 1794, shows that a quarter of the city buildings were destroyed in that year’s fire (fig. 7). This catastrophe followed a previous fire in 1788, and may help explain why so few portraits by Salazar survive. Next to the map, the reproduction of the Tremoulet’s pendant portraits were hung adjacent to a reproduction of an invoice for four portraits that Salazar executed for the DeJan family, charging between twenty and thirty pesos for each work and two extra pesos for the canvas and its wooden frame (fig. 8). Additionally, the St Louis Cathedral Finance Trustee Account Book (June 1756–May 1801) features an entry from December 2, 1800, showing that Salazar painted on commission a coat of arms of the Pope (fig. 9). The caption label uses this fact to hypothesize whether Salazar was called to New Orleans as a painter of official portraits and designer of official events.

There were several fine examples of Salazar’s portraiture in this room. The painted likenesses of Madame Michiel Fortier II and Marie Félicité Julie Fortier, show a mother and daughter in an elegant environment (fig. 10). Posing in contained, three quarter profiles, both sitters are dressed in the latest French fashion launched by Queen Marie Antoinette, with their white chemises with frilled sleeves, and their loose semi-powdered hair. The mother, who gazes at the viewer, holds a peach, a symbol of fertility, while the daughter, looking up to her mother, holds roses and star jasmine. There is a table to their right, and a green curtain swag transitions the view into an open landscape with a cloudy sky. This feature in the background is something infrequent in the work of Salazar, as most of his portraits present a neutral brownish background without any sense of real space. Next to this double portrait hung a case with four portrait miniatures of members of the Fortier family, made not by Salazar but in France, revealing the family’s close cultural ties to their country of origin. Finally, the portrait of James Mather, hanging next to the account book, reveals something new about Salazar’s work. The painting is signed “Josef De Salazar pinx,” meaning that Salazar painted the portrait. The use of “pinxit” is a convention from the early Renaissance that links Salazar to the claims that creole painters in Mexico had been making since the mid-eighteenth century to raise their professional status. The use of intellectual foundations of painting such as the term “pinxit” were among the strategies used by New Spanish artists to assert their academic standing at the same level as European artists, and it evinces that Salazar was familiar with this practice.[2]

The attention to material culture increased in the third gallery, with the display of a late eighteenth-to-early nineteenth century desk, a miniature painter’s box, a painter’s palette, and a fan, in addition to six portraits by Salazar (figs. 11, 12). The desk stood next to the portrait of Dr. Robert Dow, which shows the subject sitting at a desk similar to those exhibited (fig. 13). Dr. Dow wears a frilled chemise visible through his white vest, a white cravat, and a velvety coat, expressing his wealth and status in accordance with his position as a physician (and as official doctor in the Royal Hospital since 1799). While his right hand is hidden in his vest—a period portrait convention denoting elegant manners—his left hand holds a letter that he has seemingly just finished writing with the prominent feather pen depicted in the portrait (fig. 14). The letter is addressed to his sister, Ann Dow Ker, the recipient of the portrait. This portrait is also signed “Salazar pinxit.” Both inscriptions connect Salazar’s work with the paintings created since the sixteenth century in the Spanish territories in Europe, images that circulated widely in the Spanish colonial world through engravings. Also related to Spanish culture were the moral codes that the sitter had to embody in the portrait. For instance, Dow’s wife, Angélica Monsanto Urquhart Dow, is holding a closed fan; this female adornment functioned as an expression of modesty and chastity at the time (fig. 15).[3] Finally, the miniature portrait by Salazar displayed in the case is of Angélica Dow, and it appears as a stiffer but near replica of her face in the three-quarter portrait, painted with different clothing and background, both lightened up to bring luminosity to the image (fig. 16)

Besides material culture, the theme of family relations and issues of religion and race are brought to the fore in this gallery. Dr. Dow was a Protestant Scot who emigrated to the West Indies first, and later moved to Louisiana. He married Angélica, born into a Sephardic Jewish family from The Hague. In 1769, Governor O’Reilly had invoked the Code Noir and expelled the Jewish families like Ms. Urquhart Dow’s from Louisiana, keeping their holdings.[4] Ms. Urquhart Dow’s family moved to the West Indies for a while, but later returned home. Dr. Dow and Angélica were required to marry in the Catholic Church. Moreover, the group portrait of Antonio Méndez and his wife and two children showed a New Orleans family where one member, Antonio, was born in Havana, Cuba. According to these examples, people of influence in the eighteenth century seem to have been on the move, either chasing opportunity or being forced to relocate, having to negotiate personal religious beliefs as well as the inconveniences of travel and settling in a new place. Finally, the portrait of Marianne Céleste Dragon Dimitry reveals how racial otherness could be disguised with the performance of taste at the turn of the century, but not fifty years later, as the wall label explains (fig. 17). While Dragon Dimitry sits erect and is holding flowers according to visual codes to express refinement, her portrait was the only one in the exhibition featuring a person of darker skin.[5] Period records suggest that she had mixed racial ancestry, yet she managed to move socially upward thanks to familial ties, wealth, and education. Her father was of mixed French, Canadian, American Indian, and possibly African ancestry, and this fact had serious consequences in the mid-nineteenth century, when a nephew of Dragon Dimitry was brought to court accused of being of African descent. Although the nephew won the case, the whole Dimitry family had to undergo the shame of being scrutinized over appearance and genealogy, including Dragon Dimitry herself, evincing the rigidity of racial codification at the time.

Next followed the largest space in the exhibition with several subsections about diverse topics, such as official portraiture, clothing, family bonds, and leisure. The grandest portrait was that of Luís Ignacio María Peñalver y Cárdenas, Bishop of the Diocese of Louisiana and the Floridas (fig. 18). This portrait measures eighty-five by fifty-two inches and cost one hundred pesos, a substantial increase from the prices of twenty and thirty pesos per bust previously mentioned. The bishop appears in a full-length, life-sized portrait, in which the sitter stands in the center of a room, possibly his office. He wears a bishop’s full regalia and has adopted a blessing gesture. To the traditional curtain swag, table, chair, pen, and inkwells have been added two mitres, representing his dual bishopric of Florida and Louisiana, and a cartouche—a Novohispanic device to add text related to the sitter in a portrait—indicating the sitter’s achievements and the year of the portrait’s execution. Salazar’s daughter, also an artist, painted a copy of this portrait in 1803, according to the invoice hanging next to the portrait in the exhibition. The other official portrait was that of Don Andrés Almonester y Rojas Estrada, a man who worked as an official scribe in the Spanish court of Charles III before emigrating to New Orleans to pursue a government career (fig. 19). At the time the portrait was painted, Almonester y Rojas Estrada had become an influential benefactor, founding a hospital, a convent, and a girls’ school, and had been awarded a knighthood, as the blue-and-white bow insignia shows. He stands dressed in an official government uniform at the center of an indefinite space surrounded by a curtain swag, the family coat of arms, and the escutcheon recording his achievements.

Clothing played a key role in Salazar’s works. In his portrait, Almonester y Rojas Estrada wears the uniform of New Spain’s officers valid until 1792, in which the waistcoat was scarlet and the breeches dark blue. Vincent Rillieux is also attired in uniform, in his case with that of the Fijo de la Luisiana Regiment with a white coat and a blue collar worn over a blue waistcoat with a silver right epaulette (figs. 20, 21). He holds the tricorn hat under his right arm. And double agent General James Wilkinson appears wearing the 1790s version of an American officer’s uniform originally designed during the Revolutionary War (fig. 22). It consisted of a dark blue coat with buff trim, yellow waistcoat and breeches, and golden epaulettes; Wilkinson is also holding his tricorn under his right arm. Besides this world of uniforms there are other interesting sartorial cases, like the nearly identical choices of wealthy male civilians whose portraits hung next to each other, all wearing white cravats, white shirts and waistcoats, and black coats (fig. 23). Contained in a case was an empire gown owned by Marie Eugenie Rillieux Freret hanging next to the portrait of a young woman wearing a similar dress (figs. 24, 25). This section displayed how uniforms and civilian clothing changed over time, yet was highly coded in terms of profession, social class, and fashion.

Family bonds appeared in the most varied ways in this main space. There was a portrait of a baby, likely painted posthumously since portraits were usually painted to mark special occasions in adulthood, which speaks to the sense of loss that the family might have endured (fig. 26). The portrait of Captain Jerome Julien Vienne with one of his seven children is an unusual case, in which a father poses in uniform with his child (fig. 27). Vienne is seated at the center of the composition, and probably has his left arm akimbo to counterbalance the presence of the child on the other side of the portrait and keep the almost perfect symmetry. He wears the uniform of a Captain for the Spanish colonies, with the innovations introduced in 1792: gold lace edging the scarlet collar of the blue coat, and white waiscoat and breeches (141). The child adds a note of innocence to the scene by offering his father a rose, perhaps to celebrate his promotion as Captain, yet intended for the domestic sphere. Another representation of a domestic scene is the group portrait of The Family of Dr. Montegut (fig. 28). This depiction of children and parents together speaks not only to the new centrality of children in Anglo-American portraiture, but also to the trope of the musical family in which the family members engage in a recital to symbolize domestic harmony (163, 166). While the father holds the triangular medal of masonry showing that he belonged to the Masonic order, and the mother a basket with fruit, three of the children are holding musical instruments—a transverse flute and a square piano echoed by the real instrument standing in front of the painting—while a fourth child is in charge of turning the pages of the music book. Domestic bliss was probably one of the results of this educated form of leisure.

Recreation constituted an important theme in this exhibition, pictured not only in the musical family portrait but also in two others: the painted likeness of Clarice Le Duc Pedesclaux and her son Etienne Alexandre Pedesclaux shows an intimate scene in which the two sitters are physically interacting (fig. 29). The mother gives the son a piece of fruit in a visualization of her nurturing role, while the child holds a miniature kite, where the frill of the kite’s tail resembles the ruffled edges of his mother’s clothing and visually connects play and nurturing as essential characteristics of upbringing. More frivolous but equally revealing is the environment created with the portraits of Charles Laveau Trudeau and Charlotte Perraud Trudeau hanging above a backgammon set on a period Louisiana cabriole leg table to better illustrate the activity that is recorded in the paintings (figs. 30, 31). A game from ancient times, backgammon combines strategy with luck, and its inclusion in the portraits offers a peek into a wealthy couple’s leisure time. Their ludic engagement in the painting probably responded to a search for more informal forms of portraiture for the home, although Charles is wearing his Spanish uniform and Charlotte is dressed in high fashion, thus also projecting status for visitors to admire.

The depictions of wealth and leisure constituted the counterpoint to the invisibility of the institution of slavery in the exhibition, only briefly commented on in several of the catalogue articles. The first text panel mentioned the existence of African enslaved people in Louisiana, and the label of Captain Vienne’s portrait mentioned that he was an enslaved people’s trader. It is the catalogue that informs us of the arrival of massive numbers of enslaved people from the Senegambia region in New Orleans from 1718 to 1723; and that by the late eighteenth century, every upper class family of Mérida, Yucatán, owned one to two enslaved people who worked as domestic servants, in addition to the enslaved people who worked the fields (22, 45–46). Moreover, the reader learns that the governors protected the rights of the enslaved people in Louisiana, and that they were allowed to buy their freedom and manumit themselves constituting a new separate class. This situation was totally different on plantations though, where masters had more leeway to deal with their enslaved people. Finally, the catalogue comments on the large-scale importation of African enslaved people to Louisiana and the consequent boost of agricultural production in the 1780s, when planters expanded their fields and crops and turned New Orleans into a thriving port (61–62). This last piece of information seems especially relevant since the exhibition covers a period beginning in the 1780s when Salazar moved to Louisiana. The fact that vast amounts of enslaved people were brought to Louisiana to work in the fields and the subsequent improvement of the region’s economy seems a significant factor to be added to the reasons why Salazar migrated there.

In the same line of thought, the label of the casta painting De Español y Negra produce Mulato (From a Spaniard and a Black Woman, a Mulatto Is Produced; ca. 1785–90; first gallery) was a missed chance to discuss the presence of enslaved females originally from Africa and the phenomenon of interracial marriages. Casta painting is characterized in the catalogue and caption label by Mayela Flores Enríquez as a “painting of race” that “defined racial categories in an increasingly complex social hierarchy” (71). Perhaps due to budgetary or time constraints, no explanation was provided to help visitors understand the function of the casta painting either in this space or the exhibition at large. Casta painting is a complex genre because of the conflictive investment that both creators and patrons had in it. The extensive literature on this New Spanish pictorial genre elucidates that creole Mexican painters concocted the pseudo-ethnographic format to redefine their professional and social status in the eighteenth century. Creole artists sought to distance themselves from their competition among the Spanish, Indian, and ethnically mixed population who threatened their professional status, either by restricting their ambitions (Spaniards) or by damaging their reputation selling poor quality art (Indian and castas).[6] In response, creole painters profiled themselves as academic painters fluent in a metropolitan artistic language through the use of educated references to the art of painting and the depiction of goods with diverse material surfaces. Spanish bureaucrats constituted the main clientele, and their desire to convey the idea of a harmonious and racially taxonomized society prevailed in the genre’s creation of vignettes divided by racial categories in which nuclear family units become types for their race, a genre as clearly idealized as flawed. It would have been desirable to use the labels to address any number of complex issues, such as period fashion, material culture, colonial society, race, and ethnicity.

Finally, under the title “Nexus New Orleans,” there were two galleries displaying the Ogden Museum’s collection of nineteenth-century portraits made in New Orleans. This section had a direct correlation to the article written by Katherine Manthorne in the catalogue with the same title, and in which the author discussed several painters’ activity in the thriving city (222–41). Three portrait paintings represented Thomas Sully’s work, as he was raised in New Orleans, while the family portrait of Mrs. James Robb and Her Three Children, a New Orleans family portrayed in Philadelphia while vacationing there, corroborates Sully’s southern connection (fig. 32). The portrait of Mrs. Hore Browse Trist by Jacques Guillaume Lucien Amans presented a likeness in the Neoclassical style and a necklace displayed next to it, the same the sitter was wearing, to keep the attention on material culture from the exhibition (fig. 33). The portraits by Adolph D. Rinck and Jean Jacob Fleischbein demonstrated the presence of German-born artists in New Orleans (fig. 34). Next to Rinck’s portrait and at the other side of the door hung the Portrait of a Bespectacled Gentleman, by Jean Joseph Vaudechamp, and these two portraits framed the entrance to the second gallery of this parallel exhibit with the painting The Carr Children by William Henry Baker (fig. 35). Remarkable in this space was the presence of Dominico Canova’s Mother Louisiana, designed following a pyramidal composition to depict an allegorical scene which praised the fertility and agricultural riches of Louisiana (fig. 36). Finally, John James Audubon’s chalk and pencil portrait of Captain Gilbert Morris attested to Audubon’s artistic activity in Louisiana, besides observing and rendering birds and teaching art classes (fig. 37). While this nineteenth-century portraiture section was instructive, it came as an odd ending to a show centered on a late eighteenth-century portrait painter where examples of other artists’ work appeared very scarcely. A survey of portraiture made in the same period of Salazar might have been a more effective closing, instead of giving preeminence to the city at the very end.

The exhibition Salazar: Portraits of Influence in Spanish New Orleans, 1785–1802, was an overdue and terrific opportunity to learn more about the work of this cross-border artist within the Spanish colonial world. The figure of Salazar in his two different locations and the changing circumstances of the colonial world were conveyed in a clear manner. Moreover, the material culture focus sensitively reconstructed the daily life of late eighteenth-century elite subjects and illuminated aspects of the portraits. The presence of objects left unexplained, like the second casta painting, or the absence of discussion relating to crucial period issues, like African peoples’ enslavement, weakened the discourse of an exhibition so well defended as an example of New Southern studies. Also, the ending section of the exhibition and its emphasis on nineteenth-century artists in New Orleans, while interesting, is not as revealing as an exploration of portrait painters active in Salazar’s time. Last but not least, the lack of content written in Spanish in the exhibition undermined its stated aim of celebrating the city’s Spanish heritage. The catalogue contained four essays that were reproduced both in English and Spanish, although the other four English essays offered no translation, emphasizing a low commitment to connect with a Spanish-speaking community. Issues aside, the exhibition was innovative and beautiful to see, and it will hopefully foster the organization of future shows concentrated on the turn of the eighteenth century in the Gulf of Mexico.

Alba Campo Rosillo

PhD Candidate, Art History Department

University of Delaware

cmprsll[at]udel.edu

I am greatly indebted to the exhibition’s curator Cybèle Gontar for her generous help, and to scholars Anna Bianco and Sabena Kull for their thoughtful contributions to this text.

[1] See the museum’s presentation of the exhibition here: https://ogdenmuseum.org/exhibition/salazar-portraits-influence-spanish-new-orleans-1785-1802/.

[2] For a more detailed explanation of this phenomenon and the interrelated issues of class and race, see Susan Deans-Smith, “‘Dishonor in the Hands of Indians, Spaniards, and Blacks’: The (Racial) Politics of Painting in Early Modern Mexico,” in Race and Classification: The Case of Mexican America, eds. Ilona Katzew and Susan Deans-Smith (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009), 43–72.

[3] James M. Córdova, The Art of Professing in Bourbon Mexico: Crowned-Nun Portraits and Reform in the Convent (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014), 100.

[4] The Code Noir or Black Code was an edict dictated by Louis XIV in 1686 that established rules to control enslaved people in the French territories.

[5] To learn more about the portrait of Marianne and the construction of race in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Louisiana, see Dr. Wendy Castenell’s upcoming book based on her dissertation entitled “Color Outside the Line: Liminality and Creole Identity in Louisiana, Colonial Era to Reconstruction.” She argues that race was ambiguous and flexible, and that there was a constant tension between public and private status, allowing people to move between and among castes.

[6] Some of the key texts addressing race in the Spanish colonial world as represented in casta paintings are Ilona Katzew, Casta Painting: Images of Race in 18th-century México (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004); Susan Deans-Smith, “Creating the Colonial Subject: Casta Paintings, Collectors and Critics in Eighteenth-Century Mexico and Spain,” Colonial Latin American Review 14, no. 2 (2005): 169–204; the edited volume by Ilona Katzew and Susan Deans-Smith, eds. Race and Classification: The Case of Mexican America (Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2009); Claire Farago, and James Cordova, “Casta Painting and Self-Fashioning Artists in New Spain” in At the Crossroads. The Arts of Spanish American & Early Global Trade, 1492–1850, eds. Donna Pierce and Ronald Otsuka (Denver: Denver Art Museum, 2012); and finally, James M. Córdova, The Art of Professing in Bourbon Mexico: Crowned-Nun Portraits and Reform in the Convent (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014), chapter 6.