The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Monet and Architecture

National Gallery, London

April 9–July 29, 2018

Catalogue:

Richard Thomson,

Monet and Architecture.

New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2018.

248 pp.; 216 color illus.; bibliography; chronology; notes & references; index.

$40.00 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-1857096170

More often identified with his images of landscapes, marine scenes, and gardens, the diverse roles which buildings and manmade structures played in Claude Monet’s art have received considerably less critical attention and hence, the impetus behind The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Monet and Architecture at the National Gallery. Confidently proclaimed in the press release materials as a “rare thing” and a “landmark show,” the exhibition admirably lived up to the marketing hyperbole for the most part. As the first monographic exhibition of the Impressionist’s paintings to be staged in London for more than two decades, it justifiably merited the publicity and the unanimous praise in the British press, but the extent of its “unique and surprising” angle might not have been fully appreciated by audiences familiar with the artist’s iconic images of Rouen Cathedral, the Palace of Westminster, and the vast iron-clad roof of the Gare St. Lazare. However, as the organizing curator Professor Richard Thomson (University of Edinburgh) explained in an interview, the “new” which Monet and Architecture brings to the scholarship and the attention of visitors, is a reappraisal of Monet’s pictorial practice through the investigation of the “different aspects and uses of architecture” in his work.[1] To that end, representations of motifs ranging from rustic Dutch windmills to majestic palazzi were thematically categorized under Thomson’s conceptual framework of “The Village & the Picturesque,” “The City & the Modern,” and “The Monument & the Mysterious.” These thematic essays addressed Monet’s responses to a society that was rapidly undergoing transformative political, cultural, and technological changes during his lifetime. Spread across seven rooms in the Sainsbury Wing galleries, the panoramic scope of the exhibition encompassed over seventy-seven canvases spanning Monet’s prolific career from his early beginnings in his hometown by the Normandy coast in the 1860s–70s to the labyrinthine canals of Venice in 1908.

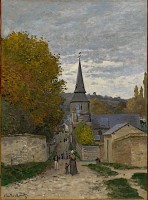

Set against an industrial grey ground, the modern typeface and minimalist title on the curvilinear entrance wall boldly announced the exhibition’s overarching theme (fig. 1). The introductory précis on the text panel highlighted the pictorial, picturesque, and psychological facets of architecture in Monet’s oeuvre. Nearby, a stand containing booklets in multiple languages replaced traditional wall labels. These were content rich and included both a chronology and maps pinpointing where Monet worked throughout Europe, but in light of his practice of returning to the same motifs years apart, labels with dates would have offered visitors a clearer chronological sense. “The Village and The Picturesque I” was the first of three rooms that illuminated the affinities between Monet’s landscapes and the picturesque: an aesthetic tradition originating in eighteenth-century England which extolled the beauty found in the irregularities of nature, the appeal of rustic country villages, the nostalgia induced by ruinous and overgrown buildings, and the reverence for old churches. The cult and culture of the picturesque not only influenced the visual arts, but also inspired landscape gardening and spawned a flourishing tourism industry. Most notably, the revival of patrimonial interest in historic buildings in nineteenth-century France, as evinced by the establishment of the Commission des monuments historiques in 1837, popularized pittoresque guidebooks, photography, and travel paraphernalia from which Thomson effectively draws innumerable comparisons to Monet’s plein-air landscapes in the exhibition catalogue. This introductory room surveyed Monet’s early artistic beginnings in Normandy during the 1860s, his two excursions to the Netherlands in 1871, and 1873–74, and his move to Vétheuil in the late 1870s. Examples such as The Hut at Sainte-Adresse (1867, Ville de Genève, Musées d’Art et d’Histoire) and Street in Sainte-Adresse (1867, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown), and The Church at Vétheuil (1878, private collection courtesy of Halcyon Gallery, London) illustrated the compositional conventions and pictorial motifs common in the iconography of the picturesque (figs. 2, 3, 4). Meanwhile, the descriptions in the booklet prompted visitors to look beyond the bucolic setting and charm of the vernacular architecture in works like Windmills near Zaandam (1871, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam) and View of Amsterdam (1874, Arp Museum Bahnhof Rolandseck, Remagen) to find telltale signs of a thriving commercial capital (figs. 5, 6). Juxtapositions were visually compelling and densely informative. For instance, the significance of the corner hang consisting of Vétheuil in Winter (1878–79, The Frick Collection, New York) and Vétheuil (1879, The Arora Collection) was multifold (fig. 7). Firstly, it established the church as a recurring picturesque subject. Secondly, the pairing demonstrated Monet’s practice of depicting the same location from different vantage points and distances as well as in varying seasons. Lastly, both village scenes exemplified Monet’s deployment of architectural elements for pictorial purposes: to add chromatic accents and tonal contrasts, impart a sense of solidity and regularity, or anchor a composition. These fundamental points in the exhibition’s thesis were further elucidated in the next gallery.

All paintings by Claude Monet unless otherwise noted.

“The Village and the Picturesque II” centered mainly on Monet’s two extended sojourns in Varengeville in 1882 and was supplemented by selected works from his trip to the neighboring fishing port of Dieppe in 1883, and a visit to Vernon near his new home in Giverny (fig. 8). The paintings generally continued the chronological trajectory from the previous room but there was a noticeable inconsistency in the inclusion of the much earlier Foot Bridge at Zaadam (1871, Musées de Mâcon, Mâcon) (fig. 9). Hung next to the text panel, this Dutch scene so evocative of seventeenth-century courtyard images by Pieter de Hooch and Johannes Vermeer, would have been a more effective complement to the Windmills near Zaandam. Considering its placement next to Monet’s rendering of rural France in The Steps (1878, private Asian collection) it can be surmised that the intention was to underscore the paintings’ shared picturesque elements and pervasive sense of nostalgia (fig. 10). Other motifs such as the well-worn medieval bridges and watermills in the Houses on the Old Bridge at Vernon (1883, New Orleans Museum of Art, New Orleans) or the rustic abode with its thatched rooftop in The Customs Officer’s Cottage, Varengeville (1882, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Cambridge, MA) are also staples in the iconography (figs. 11, 12). Comparable to the earlier canvas, A Hut at Sainte-Adresse, Thomson discerns a much less perceptible aspect: “The lonely building, set in shadow, has a psychological effect, for none of these paintings includes people, so the cottage serves as a surrogate for human presence. . . .”(52). Perhaps, but psychological resonances are not universally relatable; hence, not always grasped. Turning to the remaining paintings in the room, these largely comprised of Monet’s coastal scenes which openly divulged his avoidance of the fashionable tourist resorts in favor of nature untamed. For example, an arresting trio of Monet’s views of the vertiginous cliff at Varengeville lined the main horizontal wall (fig. 13). This grouping was boldly anchored by the monumentality of the rocky coastal landform in The Church at Varengeville, Morning Effect, (1882, The San Diego Museum of Art, San Diego). Two variations captured from a farther vantage point dramatically framed the central painting: The Church at Varengeville (1882, The Henry Barber Trust, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham) and The Church at Varengeville and the Gorge of Moutiers (1882, Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus). In all three canvases, church and village are nearly subsumed by the enormity of the cliff, the vastness of the English Channel, and the overgrowth of the surrounding vegetation. Although these structures may appear to be incidental details, such “Architectural elements were included to add formal features—a regular shape or solid mass, for instance—and a point of interest, as the human eye will instinctively seek out human elements in nature” (49).

“The Village and the Picturesque IIl” was set aglow by sunny-hued scenes of the Mediterranean coast. Monet, an avid tourist—a pastime encouraged by the proliferation of guidebooks and facilitated by expanding railway networks—traveled alone to the hilltop coastal village of Bordighera in 1884 and made inland day trips to Dolceacqua and Sasso. In 1888, he journeyed to the ancient town of Antibes in 1888 (fig. 14). Altogether, his Mediterranean campaigns produced fifty-one canvases of which three were represented in the exhibition. The distant church of Santa Maria Maddelena in View of Bordighera (1884, The Armand Hammer Collection, Los Angeles), the Città Alta tucked behind the Villas at Bordighera (1884, private collection) and the old medieval structure in Old Bridge over the Nervia at Dolceacqua (1884, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown) each typified a picturesque motif or convention (figs. 15–18). Overall, the selection of paintings was geographically and chronologically cohesive with a few obvious exceptions. The most startling of these was Monet’s The Water-Lily Pond (1899, National Gallery, London) (fig. 19). Under the subtitle The Psychological Picturesque in the catalogue, Thomson tenuously argues that the symmetry of the canvas’ nearly square format provided a sense of stability and harmony during a period of emotional hardship for the artist: his friend Alfred Sisley had died in January, followed by the death of his step-daughter Suzanne. In light of these losses and “an intellectual climate alive with the nouvelle psychologie,” it was not improbable that Monet had channelled the unconscious and perhaps a desire to escape into the world of dreams in his painting (84). To note, although some context is provided in the booklet, visitors who chose to dispense with it might have only drawn the superficial connection between the ornamental Japanese bridge in The Water-Lily Pond and its centuries-old functional counterpart in the Old Bridge over the Nervia at Dolceacqua on the opposite wall (fig. 20). The same psychological lens is applied to another square canvas located on the adjacent corner wall: Monet’s Vétheuil (1901, Von der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal). His deceased first wife Camille was buried in the village and both he and Alice were still experiencing the profound loss of Suzanne. Hence, the painting could likewise be construed “as a conscious artistic search for psychological harmony at a difficult time” (86). Lastly, though less iconic than the artist’s aqueous blooms and red-tiled village homes, Snow Effect at Giverny (1893, New Orleans Museum of Art, New Orleans) was equally incongruous in time and place (fig. 21). Given the primacy of effet and enveloppe in this nearly abstract snow-veiled scene, it would have been more ideally situated in the exhibition’s galleries on “The Monument and the Mysterious,” which chiefly focused on these atmospheric qualities across the seasons.

The following rooms “The City and the Modern I” and “The City and the Modern II” were not conceived as a chronological continuation of the previous space but as a two-part thematic investigation of Monet’s ambivalent and short-lived engagement with the modern cityscape. This period spanned a decade beginning in the late 1860s to the end of the 1870s. Part I concentrated on the major centres of population, industry, and commerce such as Paris, London, Rouen, Le Havre, and a handful of burgeoning suburbs. Part II retreated into the suburb of Argenteuil where Monet and his family lived from 1871–78: a period that witnessed a spike in the town’s building projects after the damage caused by the Franco-Prussian War. As the suburb was only 15 km northwest of the French capital and was conveniently linked to the Gare Saint-Lazare railway station, images of Argenteuil were interspersed with the occasional Parisian street scene, and a couple of his steam-enshrouded train station pictures. One of the first paintings that the viewer encountered was The Quai du Louvre (1867, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, Den Haag) which contrasted the picturesque medieval clock tower of the Saint-Etienne-du-Mont, the dome of the Panthéon, and a seventeenth-century bridge with the modern carriages, newspaper kiosks, and advertising hoardings in the foreground (fig. 22). This piece addressed a recurring theme of the exhibition’s narrative: the confluence, and at times, discordance between the old and the new. One of the most effective displays in the room is the arrangement of the View of the Old Outer Harbour at Le Havre (1874, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia), The Museum at Le Havre (1873, The National Gallery, London) and View of Rouen (1872, private collection) in a continuous line to create an impression of a harmonious horizon (fig. 23). Beyond aesthetics, the three harbor scenes collectively commented on Monet’s relationship to modernity. In the first picture of the vibrant transatlantic port, the artist captured the busy traffic between small fishing boats and large steamers on the harbor while onlookers leisurely stroll along the newly constructed quay. The work can be read as a celebratory view of the town’s prosperous industries. This outlook also applies to The Museum at the Le Havre in which the historic building is almost concealed by the flurry of masts and sails: eloquently articulated by Thomson as an instance whereby “commerce eclipses culture” (114). The last picture in the ensemble is perhaps the most ambiguous of the three in clarifying Monet’s attitude towards the changing urban landscape. The historical Rouen cathedral set atop a hill and framed by trees, is a construction drawn from the pittoresque, but the encroachment of industrialization and modernization is also evident in the aggressive verticals of the factory chimneys and the flagpole sharply projecting from the vessel. The resulting impression is “poised . . . between the picturesque and the modern” (108). To illustrate this point, juxtapositions are often provocative and insightful. For example, while the aforementioned Old Outer Harbour at Le Havre reveals the labor behind industry, The Boulevard des Capucines Paris (1873, The State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow) revels in the leisure and commerce of a bustling city (fig. 24). At the same time, the buildings are obscured by the entanglement of bare branches and almost dissolved by the blaze of the sunlight. Modernity appears attenuated or “muted.”

Other notable pieces highlighted some of Monet’s formal innovations. For instance, The Thames below Westminster (1871, National Gallery, London), The Pont Neuf (1871, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas) and The Beach at Trouville (1870, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford) all exhibit the use of a strong diagonal thrust as a perspectival device to evoke the flux and change of the metropolis, in short, the sense of the “modern momentum” in the modern metropolis (104) (figs. 25, 26). As Thomson eloquently asserts: “modern construction demanded modern composition” (104). In the next room, two visually impactful and intelligent groupings lined the two main walls (figs. 27, 28, 29). The first display chiefly consisted of scenes of Argenteuil. Examples in which man-made built structures dominate the composition, such as Argenteuil, the Bridge under Repair (1872, The Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK) and The Wooden Bridge, Argenteuil (1872, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa), were juxtaposed with pictures in which modern motifs are subdued, as in the nocturnal The Ball-Shaped Tree, Argenteuil (1876, private collection) and sun-filled Sailing Boat at Petit Gennevilliers (1874, private collection). This ensemble contrasted with the industrial smog, smoke, and cacophony of the paintings on the opposite wall: The Coal Heavers (1875, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), The Pont de l’Europe, The Gare Saint-Lazare (1887, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris) and The Gare Saint-Lazare (1877, National Gallery, London). In this latter presentation, the amorphous effects of engineered steam almost obliterate evidence of the picturesque—a persistent but not always persuasively spun thread in the exhibition. The next section, on the other hand, explored the world of meteorological phenomena and Monet’s fascination with nature’s everchanging subtleties of light and air.

Monet and Architecture culminated in the magnificence of “The Monument & the Mysterious” (fig. 30).[2] This dramatically lit gallery space showcased paintings from Monet’s Rouen and London campaigns on opposite-facing walls, perhaps to evoke their geographical location across the English Channel and works from his Venice trip in a separate room. Each city was accompanied by a text panel for additional context. Monet had embarked on two extended trips to Rouen where he painted the medieval façade of the cathedral between February and April in 1892 and again in 1903 (fig. 31). Excerpts from the artist’s correspondence in the catalogue reveal the back-breaking industry and patience that painting sur le motif required. His serial procedure entailed switching between multiple canvases in one sitting as he attempted to capture the ephemeral effects and shifting subtleties of light throughout the day under varying weather conditions. He portrayed the west façade from multiple perspectives, mainly from an apartment at the corner of the rue Grand-Point and the rue du Gros Horloge, and from the women’s dressing room on the second floor of his friend M. Lévy’s magasin de nouveautés (ladies fashion shop) at the Place de la Cathédrale! Broad and expansive, the façade functioned as a screen on which fleeting atmospheric effects were projected. But as the marvellous display of five canvases from the series highlighted, the kaleidoscopic optics and scintillating textures also materialized from the interplay between the natural elements and the façade’s ornamental and structural details (figs. 32, 33). This arrangement activated the temporal dimension which underlay Monet’s process and simulated the fleeting hours of the day. The impression was cinematic. Above all, the diaphanous veil or enveloppe enhanced the motif’s mystical associations, resulting in one of the most evocative spaces in the exhibition.

On the English side of the room, a trio of Monet’s views depicting the Houses of Parliament were also sequentially presented (fig. 34). The most luminous of the group, House of Parliament, Sunset (1904, Kunsthaus Zürich, Zürich) was enshrouded by mist and fog in crepuscular hues of blue and purple on each side. Also executed between 1899–1904, Monet’s Waterloo Bridge and Charing Cross Bridge series further emphasized the legacy of the picturesque in the artist’s choice of architectural motifs and propensity for hazy atmospheric aesthetics (fig. 35). Altogether, Monet’s journeys across the Channel inspired over one hundred canvases.

Finally, visitors transitioned into the last room, which was solely dedicated to Monet’s Venice campaign in 1908—a brief two-month trip with Alice that yielded thirty-seven paintings (fig. 36). Whether it was a picture of a church or a palazzo, the Venice pictures are almost devoid of human protagonists, save for the occasional gondola (figs. 37, 38). The two variations of The Doge’s Palace lucidly demonstrated Monet’s treatment of the massive building’s topography and the water’s expansive shimmering surface as double screens to capture the nuances of light and shadow (fig. 39). Thomson evidently saved the best for last, for “The Monument & the Mysterious” gallery was truly a magical “theatre of light” as it staged the aesthetics of the picturesque, the atmospheric effet, and connotations of the otherworldly (155). Observant audiences would have discerned that buildings successively increased in physical scale and presence in his paintings as they navigated the rooms sequentially—a trajectory that literally and figuratively added weight to the significance of architecture in Monet’s artistic enterprise.

All in all, despite some minor quibbles with the integration between the chronology and theme, The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Monet and Architecture at the National Gallery achieved its objective. The three-part conceptional framework (and the lack of labels) did encourage audiences to “look more closely. . . to get deeper into the paintings.”[3] Unequivocally, Thomson’s thesis was most convincing in “The City and the Modern” and “The Monument & the Mysterious” galleries where the built environment and its structures were the primary actors and emphatically played constructive roles as formal features. Here, real-life landmarks took front-and-center stage amidst the amorphous enveloppe and aesthetic effet in his compositions. In contrast, the examples of architecture in “The Picturesque & the Village” were peripheral in presence, incidental rather than immediate; nature presided over the built environment to the extent that the latter was often overshadowed by Monet’s overarching concern: atmosphere. Further, the psychological and occasional psychoanalytic interpretations considered in the catalogue are tenuous. Additional evidence culled from the artist’s correspondence and oeuvres would have reinforced such readings. To clarify, the catalogue is written as a monograph. From the very onset, Thomson rightly acknowledges the fact that Monet rarely articulated his interest in architecture. Accordingly, he deploys an astonishing wealth of materials—excerpts from the critical reception, comments by literary luminaries, and images from popular travel guidebooks—to substantiate his argument. Occasionally, the development of Thomson’s rich and multifaceted narrative can be arduous to navigate, as it “challengingly brings the threads of modernity and tourism, naturalism, and time” together, but when distilled down to its most elemental components, these ideas found much clearer expression on the gallery walls (19). The breadth of Thomson’s tremendous erudition is incontestable and his illuminating book an invaluable addition to the scholarship.

Corrinne Chong, PhD

Independent Scholar

corrinnecareens[at]gmail.com

[1] Professor Richard Thomson, University of Edinburgh, curator of the exhibition, interviewed by the author, National Gallery, London, April 4, 2018.

[2] To clarify, although the booklet and the text panel in the exhibition described room six as “The Monument and the Mysterious I,” there is no “The Monument and the Mysterious II.” The second thematic room does not have a title but is dedicated to Monet’s Venetian pictures.

[3] Thomson interview, April 4, 2018.