The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

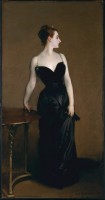

When Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau (1859–1915) presented herself in French society, both in Paris and at her country home, Les Chênes, in Paramé, people would gather to witness her beauty. Her renown made the papers throughout France, England, and the United States—from Maine to California. With her fair skin, red, upswept hair, and shapely figure, she was repeatedly described in classical terms: “a statue of Canova transmuted into flesh and blood and bone and muscle,” by one account.[1] When it came to the reviews of John Singer Sargent’s portrait of her for the Salon of 1884, the infamous Madame X, however, the critics panned the painting as displeasing and unnatural, calling out the atrocious pale skin and the indecorous draping right strap (later repainted) of the formfitting black dress (figs. 1, 2).

Susan Sidlauskas has connected the upset over Gautreau’s pallor in Madame X to concerns about illness, but the comments also signify a rejection of her self-presentation.[2] This article places Madame X within the discourse of classical reception and argues that as a “living statue,” Gautreau performed a role that observers found fashionable and alluring. It was only when her image was fixed in place on canvas that her appearance became disturbing. Gautreau claimed cultural agency within the social spaces of Parisian soirées and the beaches of Brittany, but her carefully constructed image became the object of scrutiny when displayed in the hallowed artistic space of the Paris Salon. The article further contends that conceptions about race and exoticism underlay the reaction. As an expatriate in Paris, Gautreau was considered an outsider, as was Sargent, whose parents were also from the United States. A Louisianan Creole, Gautreau was of mixed European heritage but at times was mistaken for South American, then considered an “exotic” background, an aspect that may have disallowed viewers of Madame X to regard her whiteness as embodying ideal purity. Finally, the article disproves exaggerated accounts of Gautreau’s life after the Salon, demonstrating that rather than retreating, she resumed her distinctive place in fashionable society.

A Living Statue

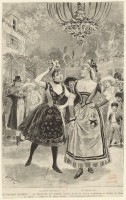

The role of a “living statue” appropriated by Gautreau was similar to that by stage actresses. Plays such as William Schwenck Gilbert’s Pygmalion and Galatea, presenting Ovid’s myth of the sculptor who fell in love with his statue of an ideal woman, Galatea, to whom Venus granted life, debuted in London in 1871 and was revived in New York in 1883.[3] Actress trade cards showing Mary Anderson in classical costume for the role circulated widely (fig. 3). Society women on both sides of the Atlantic also dabbled in “statue-ness” when they attended fancy balls. In her 1880 book Fancy Dresses Described: Or, What to Wear at Fancy Balls, Ardern Holt prescribed costumes and hairstyles for a number of allegorical and classical characters including Diana, Galatea, Night, and Twilight.[4] On March 26, 1883, Mrs. William K. Vanderbilt (Alva Erskine Smith) hosted an infamous ball at her mansion at 660 Fifth Avenue in New York, thereby solidifying her place in high society. Twelve hundred guests arrived for the party in costume from multiple eras.[5] One of the six quadrilles that were danced was titled the Dresden Quadrille and featured women dressed and powdered in white to resemble porcelain figures come to life.[6] Newspapers and magazines, like Godey’s Lady’s Book, covered the event thoroughly, and photographs of guests in costume taken by Jose Maria Mora were distributed widely via cabinet cards (fig. 4). Tobacco companies like W. Duke, Sons & Co. issued series of cards with fancy dress ball costumes in cigarette packs meant for collecting.[7]

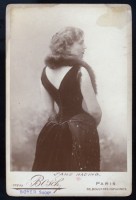

Performances of women as living statues and how they related their bodies to ancient aesthetics provide a useful framework for conceptualizing the construction of Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau’s appearance, both in the social space and in Sargent’s painting of 1883–84. Photographs from the time of her engagement to Pierre-Louis Gautreau (b. 1838–after 1924) offer a sense of the deliberate construction of her persona. The pictures were taken just prior to August 1878 when the nineteen-year-old Amélie married the forty-year-old Parisian banker and guano (fertilizer) importer.[8] Heavily staged in a photographer’s studio, the pictures provide a glimpse of the young woman before she had solidified her signature look. In a series of eight photographs, one of which is shown here (fig. 5), she wears a dark, ornamented dress with a low neckline.[9] Her hair is arranged with bangs framing her forehead followed by a braided band of hair. She wears earrings but no jewelry around her neck or in her hair.

The pictures, by an unknown photographer, are striking in their conventionality. After her marriage and introduction into French society, Gautreau was known for her conspicuousness and eccentricity. Her fashion taste and arresting appearance were the subjects of fervent comment. In 1880, a writer for the New York Herald expounded:

Mme. Gautherot [sic] may be so much as four-and-twenty. Her head is classical, and she wears her naturally wavy hair in Grecian bandeaux . . . At first sight one is literally stunned by her beauty, which her dress sets off. In shape and color the ensemble and the details are perfect. Mme. Gautherot is a statue of Canova transmitted into flesh and blood and bone and muscle, dressed by Félix, and coiffed by his assistant Émile. All her contours are harmonious. But she has yet to make the acquaintance of the Graces and to obtain possession of the girdle. I have seen her thrice in rapid succession. I know she is the loveliest creature I ever beheld coming out of the hands of a Paris dressmaker. . . . Mme Gautherot was dressed last night in a yellow silk dress, part of which was covered with a network of yellow beads and small white bugles. She also wore a necklace of diamonds, set in the classical style, a brooch, bracelets, and Greek bandalettes in her hair, sparkling with brilliants. A small Diana crescent was attached to her foremost bandalette. A murmur of admiration greeted her wherever she went.[10]

The article, representative of several others, provides a wealth of information about how Gautreau’s appearance was constructed and received. It reveals that within the two years since the engagement photographs were taken, she had assumed a classical inflection, with a countenance and hairstyle—culminating in a crescent jewel—inspired by ancient figures. That particular night, she wore an ensemble created by the maison Félix, complemented by antique-inspired jewelry. The shapeliness of her body proved noteworthy, both its contours and lack of customary undergarments. Other accounts indicate that in this guise she would sing at soirées to much acclaim—she was “l’éternelle Mme Gauthereau.”[11] The French social historian Gabriel Louis Pringué recalled that the Duchesse d’Alençon, sister of Empress Elizabeth of Austria, met Gautreau and was “enchanted to admire a living statue.”[12] On another evening, he remembered that she was “dressed in a white Grecian cloth which molded her superb figure . . . a veritable vision of the statue Diane de Gabies.”[13]

Gautreau modeled herself after mythic goddesses and after Empress Joséphine Bonaparte, retaining the look from at least 1880 through the 1890s, when she sat for portraits by Gustave Courtois in 1891 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and Antonio de La Gandara in 1897 (private collection). Her signature style of the chignon with its diamond crescent was consistently referred to as classic or Grecian.[14] From the early nineteenth century, ancient Greek and Roman beauty was considered the ideal expression of virtue.[15] Empress Joséphine popularized a classicizing style with the hair fastened in a high chignon, and curled tendrils falling over the forehead, ears, and nape of the neck.[16] At a party in February 1886, Gautreau wore an “Andromeda diadem” and at an event in December of that year her hair was “arranged like Josephine’s” and “crowned with a diadem of diamonds.”[17] Such classical allusions were associated with purity. The chignon was an age-old style in which the hair, sometimes enhanced by false pieces, was twisted into a knot at the nape of the neck or the top of the head. Most likely deriving from ancient Greece, the form was fixed and disciplined, worn by proper women in the nineteenth century, as promoted in fashion periodicals. Holt recommended it wholesale for classical costumes at fancy balls.[18]

The crescent was traditionally connected with the Greek goddesses Artemis and Selene, and the Roman goddess Diana, all identified with the moon. Holt prescribed a crescent ornament for the ball costumes of Hours, Night, Twilight, and Evening Star.[19] The emblem also would have been well known from such ancient sculptures as Selene (called Diana Lucifera by the Romans) in the Capitoline Museums in Rome (fig. 6), which had been reproduced in prints since the late eighteenth century.[20] Gautreau was referred to as “la belle Diane”; in turn, she was said to resemble Diane de Poitiers (1499–1566), a French noblewoman in the court of Francis I who also wore a crescent in her red hair.[21] At the time, Diana was associated with upper-class women as well as with “professional beauties,” as Gautreau was called, not yet with the femme fatale, as she would be in the early twentieth century.[22] Another professional beauty was Lillie Langtry (born Emilie Charlotte Le Breton; 1853–1929), a mistress of the Prince of Wales who became famous in London and turned to acting in 1881 when her husband, Edward Langtry, declared bankruptcy.[23] Theater designer and illustrator W. Graham Robertson recalled: “For the first time in my life I beheld perfect beauty. The face was that of the lost Venus of Praxiteles.”[24] She often posed for paintings and photographs wearing cosmetics (in 1899 she began promoting “Lillie Powder”) and a prominent crescent ornament (fig. 7).[25] Gautreau was referred to as the “Mrs. Langtry of France.”[26] In the late 1880s, Sargent’s master, Carolus-Duran (Charles-Auguste-Émile Durant), and Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta would paint such eminent sitters as Madame Edgar Stern and the Marquise d’Hervey Saint-Denys, respectively, in the guise of Diana, both with crescent jewels in their hair.[27] In 1888, the Journal de Genève noted the trend of women posing for portraits wearing a diamond crescent, citing their imitation of Gautreau, who wore it “with so much success.”[28]

Whiteness

Enhancing the effect of ideal sculptural beauty was the matter of Gautreau’s whiteness. Gautreau famously lightened her skin, the hue of which she apparently achieved by applying rice powder. The cosmetics (maquillage) were referred to as her “enamelling” and were thought to augment her striking profile.[29] Author and critic Judith Gautier, a friend of Sargent, described her complexion as “where heliotrope is steeped in pink,” and Le Galois proclaimed her a “goddess of the night, all golden powder.”[30] The communicative value of her pale skin may be considered an attempt to accentuate the whiteness of her “make up” and claim a classical, as well as aristocratic, ideal. By whitening her skin, Gautreau was reaffirming her lightness, if not taking away color. She also added color by reddening her ears and hair, a choice that further emphasized her fairness, in the vein of blushing, a phenomenon that Angela Rosenthal has explicated as signifying whiteness and virtue.[31] Further, social historian Lois W. Banner explains that in the United States in the nineteenth century, along with a slim waist and petite nose, mouth, feet, and hands, a pale complexion was associated with the refinement of nobility.[32]

An expatriate in Paris, Gautreau was already considered an outsider, but she was also associated with the exotic. At least two writers mistook her as South American, linking her with her husband’s business dealings in that continent. After misstating her home country as Peru, in spring 1880 The Sunday Herald (Washington, DC) wrote:

Her husband is not Mr. Mitford, and she has not a dollar of Commodore Vanderbilt at her banker’s. Those diamonds were bought with the produce of sugar cane and coffee plantations. She was brought up in sub-tropical ease and listlessness, and among halfbreeds who have no notions about women’s rights, higher planes of thought, and transcendentalism. Her husband is a rich importer of colonial goods at Nantes and happy to see her enjoy herself in her own way.[33]

In addition to insulting her husband’s nouveau-riche status, making money off the colonies, the writer disparaged her proximity to indigenous peoples, denouncing them as unsophisticated. American journalist Theodore Child also referred to her as South American, and the French critic Louis de Fourcaud described her as “the Parisian woman of foreign extraction.”[34] In a genealogical study of the Avegno family, Robert de Berardinis classifies Gautreau as Creole, “a New Orleans blend of German, Austrian, French, Acadian, and Italian stock.”[35] The term “Creole,” meaning “mixed,” was used to refer to descendants of settlers in colonial Louisiana. Although the Avegno family was of European heritage, many other New Orleans Creoles possessed a blend of European, African, and Caribbean backgrounds, which seems to have led to erroneous assumptions about Gautreau. As New York’s Town Topics remarked in July 1887, “nine out of ten persons in the north think a Creole is a mulatto. In Louisiana to be a Creole is to be a patrician, a Mayflower New Englander, a Knickerbocker. Mrs. James Brown Potter, ‘the beautiful Mme Gauthereau [sic],’ General Beauregard, are Creoles.”[36] Her dual identity further aligned her with the image of Empress Joséphine. Joséphine hailed from an aristocratic Creole family from Martinique, a French colony in the Carribbean, and shrewdly incorporated elements of foreign costume into her dress as a way of communicating imperial reach.[37] As Joséphine had done for several portraits, in Madame X, Gautreau chose an uncorseted dress to offset her sinuous physique, a practice that recalled local preferences in warm climates like the American South.[38]

Joseph Baillio suggests that Gautreau’s hair ornament could refer to the “Crescent City,” a nickname for New Orleans, a cleverly placed tribute to the city where she was born and where her family held landed status.[39] New Orleans was known for its celebrations of Mardi Gras, derived from France, with masked parades and balls that were especially embraced by the Creole population. The festivities, held in the days leading up to Lent, were defined by masquerading, public display, and revelry; cross-dressing and white- and black-face were common practices. Engrained in New Orleans culture even before the city was annexed by the United States in 1803, Mardi Gras would have been part of the Avegno family’s milieu in Louisiana and perhaps also in Paris, where Americans also celebrated the holiday.[40] In June 1879, Harper’s Bazaar reported on American society in Paris: “As Mardi-Gras approaches, the climax of social activity is reached, and all sorts of novel entertainments take place.”[41] The tawdry side of dressing up for Mardi Gras, even if one were to don classical garb (the holiday is thought to have pagan roots), points to another, parallel appropriation of allegorical and ancient costume. Burlesque shows often attempted to legitimize their productions by placing scantily clad actresses within a classical stage setting.[42] For example, the teenage American burlesque star Daisy Murdoch became famous for playing Cupid in Orpheus and Eurydice (1883–85) for the Bijou Opera Company, and a number of trade cards were issued showing her in a skimpy, sleeveless costume (fig. 8).[43]

As Albert Boime, Richard Ormond, and Elaine Kilmurray have shown, Gautreau and Sargent were both Americans infiltrating the social scene in Paris, one courting high-end commissions and the other the most desirable acquaintances and soirées.[44] Andrew Stephenson has explored Sargent’s outsider status in several cities in Europe and the United States as contributing to the artist’s ability to capture the multiple and shifting identities of his sitters, especially in relation to nationalisms and race.[45] Sargent openly admired Gautreau’s use of cosmetics, writing in February 1883 to his friend Vernon Lee, an author on aesthetics, and particularly sculpture: “Do you object to people who are fardées to the extent of being uniform lavender or blotting paper colour all over? If so you would not care for my sitter. But she has the most beautiful lines and if the lavender or chlorate-of-potash-lozenge colour be pretty in itself I shall be more than pleased.”[46] Sargent tended toward theatrical sitters, and as Sidlauskas points out, in this era of Baudelaire, who wrote in favor of the artifice of cosmetics, Sargent did not mind, even relished, painting “a woman who had already painted herself.”[47] To Sargent, Gautreau’s use of cosmetics may have signaled an exoticness—in Lee’s words, “the exotic, far-fetched quality which always attracted John Sargent”—further drawing him toward Gautreau as a compelling subject.[48]

Soon after they met in 1882, Sargent wrote to his friend Ben del Castillo: “I have a great desire to paint her portrait and have reason to think she would allow it and is waiting for someone to propose this homage to her beauty.”[49] Gautreau agreed to have her image immortalized again—Zoe-Laure de Châtillon had already made a portrait—and this time by an up-and-coming society painter.[50] She sat for Sargent beginning in winter 1882–83 in Paris, and then in summer 1883 at Les Chênes, promising him she would “pose morning and night for a week or two,”[51] but there were days when Gautreau seemed “quite bored and would like to be in Paris.”[52] Sargent executed numerous studies before settling on the final composition, and he continued to make adjustments to the canvas throughout the painting process.[53] In advance of the Salon, Carolus-Duran reportedly praised the painting, and upon Sargent’s completion of the canvas, Le Gaulois wrote that it “is said to be remarkable.”[54] Notoriously, when the finished painting was hung at the Salon of 1884, with the title Portrait de Mme ***, it was reproached by critics throughout Europe and the United States who objected to Gautreau’s overly pale skin and the draping strap of the dress.[55] Although they spoke about her sculptural beauty and modeling, the classical reception of the painting differed significantly from her reception in society.

The Classical Reception of Madame X

Having a new understanding of Gautreau’s penchant for a classically inspired presentation, it is now possible to look anew at Madame X and detect an effort to maintain that style in her painted representation. She is positioned in a cameo profile, and her red, upswept hair is ornamented by the crescent. The two-piece satin and velvet dress is unembellished aside from the jeweled straps, differing from the lacey, bustled designs that were then promoted in fashion magazines (fig. 9). Justine De Young recently demonstrated that although unusual, the dress in Madame X is not an anomaly for the early 1880s, citing sitters wearing black dresses with plunging necklines in Sargent’s portrait Mrs. Harry Vane Milbank of 1883–84 (private collection), and in two portraits of Madame Louis Singer in 1884 by Paul Jacques Aimé Baudry (Musée du Petit Palais, Paris, and private collection). She also specifies an evening dress by Hoschedé Rebours of about 1885 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[56] To this group may be added the cabinet cards of actress Jane Hading, also a client of Félix, in a black velvet dress with a plunging neck and back line from about 1885 (fig. 10).[57]

The designer of the ensemble in Madame X is unknown, but in contemporary accounts only one house has been associated with her—the aforementioned maison Félix.[58] Félix, a couturier on the desirable rue de Faubourg Saint-Honoré was in business for fifty-five years and was in direct competition with the House of Worth.[59] The firm was founded by Joseph-Augustin Escalier (born ca. 1815) in 1846 and subsequently owned and run by brothers Auguste Poussineau (1831–1910) and Émile Martin Poussineau (called “Félix”; 1841–1930) until it closed its doors in 1901.[60] The maison dressed members of European royalty and high society, including Empress Eugénie, Queen Margherita of Italy, Queen Maria Dona Pia of Portugal, Princess Maud of Denmark, and Elisabeth, de Caraman-Chimay, Comtesse de Greffulhe.[61] After 1870, Félix became known for its actress clients, the most famous of whom were Sarah Bernhardt, Sophie Croizette, Ellen Terry (subject of Sargent’s 1889 portrait), and Lillie Langtry, as well as Réjane, Jane Hading, Ada Rehan, and Anna Marie Louise Damiens Judic (fig. 11).[62] As they did with Worth, Doucet, and Redfern, singers and actresses pursued Félix and favorably boosted business. The maison embraced the power of performers’ influences on the latest outfits, making “a specialty of actresses’ wardrobes.”[63] In 1882, the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin wrote, “The clever man tells the great ladies that the actresses copy from them—and he says to the actresses that they set the fashions for the great ladies. So both classes are pleased, and no one is any the worse.”[64]

A highly respected couturier, Félix was known for embodying “Parisian taste: so elegant, so pure, so simple, opposed to fake flash and false pretension.”[65] Located at 15, rue Faubourg-Honoré from at least 1857, the business eventually employed more than three hundred workers and by 1888 offered lingerie, hosiery, flowers, bonnets, muffs, “and a hairdresser at one’s service.”[66] There is no evidence that the maison was responsible for creating the black dress in Madame X, but Félix was known for producing a slim and refined silhouette that would have suited Gautreau’s figure and taste.[67] Given Félix’s involvement in designing stage outfits for actresses and singers, the dress may be regarded as a costume, part of Gautreau’s performance as a living statue. This is not to say that the dress is neoclassical—it certainly differs from the white, unstructured, Empire-waisted gowns of the 1790s to 1810s—but it demonstrates an effort toward timelessness that dissociates it from the embellished dresses with decorative patterns and voluminous skirts that appeared in fashion periodicals and those that she wore at the time of her engagement. As fashion historian Harold Koda explains, “Often, the semiotic elements that transform contemporaneous fashion into a classical style are derived not from the somewhat scant evidence of the realities of classical dress but from representational effects seen in sculpture and painting.”[68] In addition, the exposure of her neck, arms, and shoulders—even with one shoulder completely bare—would have been familiar from ancient goddess sculptures and neoclassical sculptures of the early to mid-nineteenth century in Europe and the United States.[69] As Koda points out, a chiton (a basic sleeveless garment), baring one or both breasts was associated with sculptural representations of Artemis, among other goddesses, as well as Amazons (fig. 12).[70]

The American actress Mary Anderson starred as Galatea, Pygmalion’s living statue, in the aforementioned performance of Gilbert’s play in 1883. Cabinet cards offer a sense of how her classical costume was interpreted on stage—in one image the upper right armband is in the same placement as Gautreau’s strap (see fig. 3).[71] The same year, Anderson also played the role of Parthenia in Friedrich Halm’s Ingomar, the Barbarian in London, for which images also circulated.[72] For Gautreau’s classical enactment in Sargent’s painting, her pale skin appears as smooth as alabaster, especially in cameo-like contrast to the black dress and red hair.[73] Her right hand grasps the top of a mahogany table, its legs decorated with what appear to be Sirens, mythic winged female figures known for their alluring, but dangerous singing, perhaps a reference to Gautreau’s reputation as a chanteuse.[74] Finally, she stands in a timeless, nondescript space.

The critics’ accounts make clear, however, that her classical mode in the Salon painting was unacceptable. Although writers like Gautier spoke of Gautreau’s “chimerical beauty” and invoked Diana and other goddesses in their reviews, in the end, the exposure of her whitened flesh was considered distasteful.[75] William Crary Brownell questioned the decency of Gautreau’s “maquillage and décoloration” (makeup and discoloration) and exposure of so much of her body, which he associated with artifice, rather than purity.[76] In La Nouvelle Revue, Paul Arène reported Salon visitors exclaiming, “the hair is dyed, the flesh made-up.”[77] The artist Marie Bashkirtseff, who viewed Madame X at the Salon, recalled, “she paints her ears rose and her hair mahogany. The eyebrows are traced in dark mahogany color, two thick lines.”[78] The Art Amateur appreciated the “perfectly, austerely plain” black dress, but said that her face resembled “a female clown in a pantomime.”[79] Most other writers regarded the dress, especially the fallen right strap, as indecorous and the pale skin as deathlike pallor, rather than the pure white, sculptural ideal.[80] William Sharp wrote in London’s Art Journal: “The flesh painting—and Mr. Sargent has not stinted himself as to space—has far too much blue in it, and the result of the artist’s experiment or wilful indifference, whichever it is, more resembles the flesh of a dead than a living body.”[81] Sidlauskas has connected the comments about lifelessness to concerns at the time about tuberculosis and syphilis, and the use of cosmetics to mask illness, but comments such as those by Sharp also resonate as a rejection of Gautreau’s self-presentation in the painting.[82]

The critics’ repudiation of Gautreau’s statue-ness in the portrait may be understood as a refusal of her cultural agency, and the transformation of her into an object of scrutiny. In other words, there was a schism between the classical reception of Gautreau, the woman, in society, and of her representation in a formal Salon painting. Gautreau’s performances occurred ephemerally at parties and by the seaside, and to a self-selecting audience who were familiar with the role of living sculpture from the theater, especially burlesque. There, the way she moved her body through space was a key aspect of the performance. As the American painter Edward Simmons recalled of seeing Gautreau in Paris: “Representing a type that never has appealed to me (black as spades and white as milk), she thrilled me by the very movement of her body. She walked as Vergil speaks of goddesses—sliding—and seemed to take no steps.”[83]

Her whitened, classical aspect only became problematic when Sargent fixed it on canvas and presented it in the elevated world of the Parisian Salon. In his review, Claudius Lavergne for L’Univers disparaged the effort: “painters must not literally translate these flowers of rhetoric.”[84] In the artistic space of the Salon, Gautreau lost her ability to control her self-presentation, and her appropriation of a classicizing character came into question when it was negatively associated with theatricality as well as her outsider, Creole heritage.

The aftermath of the Salon bears out the crucial difference in reception between Gautreau the woman and Gautreau the portrait subject. Importantly, Gautreau was initially pleased with the painting, writing as a postscript on Sargent’s letter to their mutual friend, the writer and translator Emma Marie Allouard-Jouan, in summer 1883 from Les Chênes: “Mr. Sargent made a masterpiece of the portrait, I am anxious to write it to you because I am certain he will not tell you.”[85] After hearing the negative reactions of the press and of her socially conscious mother, however, she turned against the painting, while Sargent defended it by saying that he painted her “exactly as she was dressed.” He refused to remove the painting from the Salon, but eventually repainted the strap of the right shoulder in an upright position.[86] Finding that “For a year or two in Paris, I had so few commissions, probably the effect of the Gautreau disaster,” he settled in London in spring 1886.[87] In 1916, Sargent sold the painting to the Metropolitan Museum, having declared the previous year to director Edward Robinson: “I suppose it is the best thing I have done.”[88]

Contrary to sensationalized accounts that have Gautreau retreating from society and living as a recluse after the Salon, she promptly resumed her role as a living statue. She continued to wear classical dress and jewelry—in February 1885, the New York Times referred to her as a “piece of plastic perfection.”[89] Three years after the Salon, she made a theatrical debut (“to follow Mrs. Langtry’s example and go on the stage in earnest”), and she went on to host and sing at parties as late as 1902.[90] The brisk resumption of Gautreau’s activity underscores her control over her presentation in the social space, an agency that was only briefly lost while her portrait hung on the wall of the Salon. By reading Madame X through the lenses of classical reception and whiteness, this article has broadened our understanding of how Gautreau’s complex role in society complicated the response to her most famous portrait.

All translations are by the author unless otherwise indicated.

[1] “La Belle Americaine,” New York Herald, March 30, 1880.

[2] Susan Sidlauskas, “Painting Skin: John Singer Sargent’s ‘Madame X,’” American Art 15 (Autumn 2001): 23–25.

[3] In her 2015 article, “Living Statues and Neoclassical Dress in Late Eighteenth-Century Naples,” Amelia Rauser expertly parses the actress Emma Hart’s role as living statue, an “artwork come to life.” She explains that Ovid’s myth of Pygmalion inspired the evocations of living statues like Hart. The present article is indebted to Rauser’s explication of how Hart elided the boundaries of artistic and social spaces, which presented challenges for some viewers. Amelia Rauser, “Living Statues and Neoclassical Dress in Late Eighteenth-Century Naples,” Art History 38, no. 3 (June 2015): 462–87. See also Amelia Rauser, “Vitalist Statues and the Belly Pad of 1793,” Journal 18, no. 3 Lifelike (Spring 2017): n.p.; see text after note 27; and see note 23. See also Gail Marshall, Actresses on the Victorian Stage: Feminine Performance and the Galatea Myth (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 16–29; 104–5.

[4] Ardern Holt, Fancy Dresses Described: Or, What to Wear at Fancy Balls (London: Debenham and Freebody, 1880), 2.

[5] Susan Gail Johnson, “Like a Glimpse of Gay Old Versailles: Three Gilded Age Balls,” in Gilded New York: Design, Fashion, and Society, exh. cat., Museum of the City of New York, ed. Donald Albrecht and Jeannine J. Falino (New York: the Monacelli Press, 2013), 89. For more on the social mores of dress requirements and the extravagance of balls, see Diana De Marly, Worth: Father of Haute Couture (London: Elm Tree Books, 1980), 60–74; Sophia Murphy, The Duchess of Devonshire’s Ball (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1984), passim; Eric Homberger, Mrs. Astor’s New York: Money and Social Power in a Gilded Age (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 120–48; Greg King, A Season of Splendor: The Court of Mrs. Astor in Gilded Age New York (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2009), 209–20; Amy De la Haye and Valerie D. Mendes, The House of Worth: Portrait of an Archive (London: V&A Publishing, 2014), 114.

[6] Susannah Broyles, “Vanderbilt Ball—How a Costume Ball Changed New York Elite Society,” New York Stories (blog), Museum of the City New York, August 6, 2013, https://blog.mcny.org/2013/08/06/vanderbilt-ball-how-a-costume-ball-changed-new-york-elite-society/.

[7] For example, “An Easter Ball,” Godey’s Lady’s Book 106, May 1883, 458. The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection of Printed Ephemera in the Department of Drawings and Prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art contains thousands of “tobacco cards.” See Rebekah Burgess Abramovich, “Becoming the Advertisement: Daisy Murdoch as ‘Cupid’ on 1880s Tobacco Cards,” Now at The Met, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, July 29, 2014, https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2014/becoming-the-advertisement-daisy-murdoch.

[8] Deborah Davis reproduces the bride’s signature on the marriage contract (Contract de Mariage entre M. Pierre-Louis Gautreau et Mademoiselle Avegno. Paris, M. Deves, notary, 1878); Deborah Davis, Strapless: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madame X (New York: Penguin, 2003), 42.

[9] The group of photographs in the Médiathèque de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine, Charenton-le-Pont, France, also includes two of Virginie Amélie Avegno in her wedding dress, and two of Pierre Gautreau in ceremonial military uniform.

[10] “La Belle Americaine,” New York Herald, March 30, 1880. The writer overestimated Gautreau’s age.

[11] The quotation is from “Nouvelles and Echos,” Gil Blas, April 20, 1883, 1 (with the surname spelled “Gauthereau,” one of several variants); see also “Nouvelles and Echos,” Gil Blas, March 1, 1882, 1; “Le Monde et La Ville,” Le Gaulois, January 4, 1884, 2; “Nouvelles and Echos,” Gil Blas, February 12, 1884, 1.

[12] “enchantée d’admirer une statue vivante.” Gabriel Louis Pringué, 30 Ans de Dîners En Ville (Paris: Revue Adam, 1948), 212.

[13] “vêtue d’une chlamyde blanche moulant son corps et sa taille superbe . . . [une] véritable vision de la statue de la Diane de Gabies.” Pringué, 212.

[14] See, for example, “Télégrammes et Correspondences,” Le Figaro, August 30, 1881, 3; “La Vie Parisienne, Les Belles Parlementaires,” Gil Blas, January 30, 1902, 1; Pringué, 212.

[15] Harold Koda, Goddess: The Classical Mode (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003), 11; Aileen Ribeiro, Facing Beauty: Painted Women and Cosmetic Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 226.

[16] For Joséphine’s style, see Heather Belnap Jensen, “Parures, Pashminas, and Portraiture, or, How Joséphine Bonaparte Fashioned the Napoleonic Empire,” in Fashion in European Art: Dress and Identity, Politics and the Body, 1775–1925, ed. Justine de Young (London: I. B. Tauris, 2017), 36–59.

[17] “Nouvelles and Echos,” Gil Blas, February 13, 1886; “Old World Topics,” The Milwaukee Sentinel, December 20, 1886, 4; “Fashion Miscellany,” The Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago), December 26, 1886, 16.

[18] Holt, 5.

[19] Holt, 43–44, 58, 83, 87.

[20] Trevor J. Fairbrother connected the crescent symbol in Madame X with sculptures in the Louvre, citing the Artemis of Gabii, which Pringué had mentioned, although a crescent is not detectable, and Diana the Huntress by Jean-Antoine Houdon (1790; Louvre CC 204). Trevor J. Fairbrother in A New World: Masterpieces of American Painting 1760–1910, ed. Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., Carol Troyen, and Trevor J. Fairbrother (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1983), 300. He first suggested a classical referent in “The Shock of John Singer Sargent’s Madame Gautreau,” Arts Magazine 55, January 1981, 96n17. The Selene sculpture was first reproduced in Raccolta di statue antiche esistenti nei Musei, Palazzi e ville di Roma. Parte prima, contenente le statue del Museo Capitolino (Rome, 1785), as Diana Lucifera, board XVII.

[21] “Nos Echos,” Le Gaulois, November 10, 1881, 1; “La Soirée Parisienne,” Gil Blas, January 13, 1890, 3; “A Parisian Professional Beauty,” from the Boston Beacon, printed in the Morning Oregonian (Portland, OR), July 23, 1891, 4.

[22] Critic Jules Claretie referred to Gautreau as the “professional beauty who turns all heads” (“la professional beauty qui fait tourner ou retourner toutes les têtes”). Jules Claretie, “La Vie à Paris,” Le Temps, May 16, 1884, 3; translated by Sarah McFadden; Albert Boime, “Sargent in Paris and London: A Portrait of the Artist as Dorian Gray,” in John Singer Sargent, ed. Patricia Hills (New York: Abrams, 1986), 89.

[23] See Catherine Hindson, “‘Mrs. Langtry Seems to Be on the Way to a Fortune’: The Jersey Lily and Models of Late Nineteenth-Century Fame,” in In the Limelight and under the Microscope: Forms and Functions of Female Celebrity, ed. Diane Negra and Su Holmes (New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011), 24.

[24] W. Graham Robertson, Time Was (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1931), 69. See Marshall, 11–12.

[25] Kathy Lee Peiss, Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1998), 48; Ribeiro, 274; Hindson, 32. See also Julius L. Stewart, A Hunt Ball, 1885, private collection, ex. coll., Essex Club, Newark, in which Langtry is depicted wearing a crescent hair jewel.

[26] R[obert] H[arborough] Sherard, “A Reception at the Elysée,” The Graphic, May 30, 1891, 613.

[27] The paintings are paired in Marie Simon, Fashion in Art: The Second Empire and Impressionism (London: Zwemmer, 1995), 84. Carolus-Duran, Madame Stern, 1889, Musée du Petit Palais, Paris (PPP3619); and Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta, The Marquise d’Hervey Saint-Denys as Diana, 1888, Musée d’Orsay, Paris (20417).

[28] “qui sous ce costume a eu tant de succès.” “Etranger: France,” Journal de Genève, February 23, 1888, 2. An engraving of 1891 shows Gautreau seated prominently at a reception at the Elysée, crescent jewel high on her head. Another woman wearing a crescent in her hair enters the scene, gazing at Gautreau. Engraving, A Reception by Madame Carnot at the Elysée, Paris, The Graphic, May 30, 1891, 614–15.

[29] Stephenson introduces the notion of whiteness and classical precedents in relation to Madame X; Andrew Stephenson, “‘A Keen Sight for the Sign of the Races’: John Singer Sargent, Whiteness and the Fashioning of Anglo-Performativity,” Visual Culture in Britain 6, no. 2 (Winter 2005): 219–20. For Gautreau’s use of face powder, see Sidlauskas, 11; Trevor J. Fairbrother, John Singer Sargent: The Sensualist (Seattle: Seattle Art Museum; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 216n16; Dorothy Moss, “John Singer Sargent, ‘Madame X’ and ‘Baby Millbank,’” The Burlington Magazine 143, no. 1178, May 2001, 270; Deborah Davis and Elizabeth Oustinoff, “Madame X Speaks,” The Magazine Antiques 164, no. 5, November 2003, 118, 120; Davis, 56. Theodore Child wrote, “she has carried to unparalleled perfection the art of maquillage, enamelling, and of eccentricity in costume and coiffure.” Theodore Child, “Society in Paris,” Littell’s Living Age, May 8, 1886, 362. Aileen Ribeiro explains that “enamelling” referred both to thick white paint on the face and a process of filling in wrinkles and marks with lead or arsenic paste; Ribeiro, 252–53. The term “make-up” was not widely used until the 1890s; Ribeiro, 281. See also Peiss, Hope in a Jar, 27.

[30] “ce teint où l’héliotrope est pétri avec la rose.” Judith Gautier, “Le Salon,” Le Rappel, May 1, 1884, 1; “en déesse de la nuit, toute poudrée d’or,” “Nos Echos,” Le Gaulois, February 27, 1884, 1.

[31] Angela Rosenthal, “Visceral Culture: Blushing and the Legibility of Whiteness in Eighteenth-Century British Portraiture,” Art History 27, no. 4 (September 1, 2004): 563–92. See also Mary Cathryn Cain, “The Art and Politics of Looking White: Beauty Practice among White Women in Antebellum America,” Winterthur Portfolio 42, no. 1 (Spring 2008): 33–35.

[32] Lois W. Banner, American Beauty (New York: Knopf, 1983), 81. See also Peiss, Hope in a Jar, 39–40.

[33] “La Belle Americaine,” The Sunday Herald (Washington, DC), April 4, 1880, n.p. Gautreau and Company had dealings in Peru. For example, see “The Peruvian Investigation,” Bangor Daily Whig and Courier (Bangor, ME), May 12, 1882.

[34] “la Parisienne d’origine étrangère.” Louis de Fourcaud, “Le Salon de 1884 (Deuxième Article),” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 29, no. 6, June 1884, 482–84; translated in Boime, 90–91. Child, “Society in Paris,” 362. See also Stanley Olson, John Singer Sargent, His Portrait (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1986), 101–2.

[35] Robert de Berardinis, “‘Madame X’: Virginie Amélie ‘Mimi’ Avegno (Mme. Gautreau) and a Family Note to Art History,” National Genealogical Society Quarterly 90, no. 1 (March 2002): 65.

[36] Town Topics (New York), July 28, 1887, 9.

[37] Jensen, 36–59.

[38] Jensen, 53.

[39] Joseph Baillio, in The Odyssey Continues: Masterworks from the New Orleans Museum of Art and from Private New Orleans Collections (New York: Wildenstein and Co., 2006), 72.

[40] Henri Schindler refers to the golden age of Mardi Gras as 1870 to 1930. Henri Schindler, Mardi Gras Treasures: Costume Designs of the Golden Age (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 2002), 7–9; Henri Schindler, Mardi Gras Treasures: Jewelry of the Golden Age (New Orleans, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 2006), 8; see also Jennifer Atkins, New Orleans Carnival Balls: The Secret Side of Mardi Gras, 1870–1920 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2017), 96–103.

[41] “American Society in Paris,” Harper’s Bazaar, June 14, 1879, 382–83.

[42] Laura Monrós Gaspar, “‘The Fairest One with Golden Locks’: Parodying Helen on the Modern Stage,” in Adaptations, Versions and Perversions in Modern British Drama, ed. Ignacio Ramos Gay (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014), 15–16.

[43] Abramovich, “Becoming the Advertisement.” Now at The Met, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, July 29, 2014, https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2014/becoming-the-advertisement-daisy-murdoch. See also Jack W. McCullough, Living Pictures on the New York Stage (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1983), 93–96; Robert C. Allen, Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1991), 197–98.

[44] Boime, 86–88; Richard Ormond and Elaine Kilmurray, eds., John Singer Sargent: Complete Paintings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 1:113.

[45] Stephenson, “‘A Keen Sight for the Sign of the Races’: John Singer Sargent, Whiteness and the Fashioning of Anglo-Performativity,” 207–25. See also Andrew Stephenson, “Locating Cosmopolitanism within a Trans-Atlantic Interpretive Frame: Critical Evaluation of Sargent’s Portraits and Figure Studies in Britain and the United States c. 1886–1926,” Tate Papers, no. 27, Spring 2017, accessed October 17, 2017, http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/27/locating-cosmopolitanism.

[46] Sargent to Vernon Lee, February 10, 1883, Ormond family archive. Published in Ormond and Kilmurray, 113. “Fardées” translates to “a made-up woman.” Sidlauskas suggests that Sargent fetishized Gautreau’s skin; Sidlauskas, 14. See also Alison Syme, A Touch of Blossom: John Singer Sargent and the Queer Flora of Fin-de-Siècle Art (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010), 141–43. Vernon Lee was the pseudonym of Violet Paget (1856–1935). Her essay “Child in the Vatican” expounds upon the dehumanization of sculptures within museum settings. Vernon Lee, “Child in the Vatican,” in Belcaro: Being Essays on Sundry Aesthetical Questions (London: W. Satchell, 1881).

[47] Sidlauskas, 11; based on William Crary Brownell, an American writing for London’s Magazine of Art about the Salon: “the lady herself was superficially a work of art.” William Crary Brownell, “The American Salon,” The Magazine of Art (London), no. 7, 1884, 494. Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life,” in The Painter of Modern Life: And Other Essays, trans. Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon, 1964), 31–34. For Sargent’s theatrical subjects, see “The Academy of Design,” The Art Amateur 24, no. 2, January 1891, 31; Leigh Culver, “Performing Identities in the Art of John Singer Sargent” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1999), 1–96; Fairbrother, John Singer Sargent: The Sensualist, 81–83; Stephenson, “‘A Keen Sight for the Sign of the Races,’” 218–20.

[48] Quoted in Evan Charteris, John Sargent (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1927), 248–49.

[49] Letter, Sargent to Ben del Castillo, 1882. Quoted in Charteris, 59; see also Ormond and Kilmurray, 113.

[50] The portrait by Zoe-Laure de Châtillon is in the collection of Alfredo López (location unknown; information provided by Angèle Parlange, descendent of Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau; email message to author, July 12, 2017).

[51] “Elle m’a promis de poser matin et soir pendant une ou deux semaines.” Letter from Sargent to Emma Marie Allouard-Jouan, Summer 1883, SC.SargentArchive.7.5, The John Singer Sargent Archive, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (All translations from the Sargent letter archives in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, are by that institution.) On the sittings, see also Trevor J. Fairbrother, John Singer Sargent (New York: Abrams, 1994), 45–48; Ormond and Kilmurray, 113; Stephanie L. Herdrich and H. Barbara Weinberg, American Drawings and Watercolors in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: John Singer Sargent (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000), 15; Dorothy Mahon and Silvia Centeno, “A Technical Study of John Singer Sargent’s Portrait of Madame Pierre Gautreau,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 40 (2005), 121–24.

[52] “Elle a l’air de bien s’ennuyer et voudrais être à Paris.” Letter from Sargent and Gautreau to Emma Marie Allouard-Jouan, Summer 1883, SC.SargentArchive.1, The John Singer Sargent Archive, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

[53] Fairbrother, John Singer Sargent, 45–46; Herdrich and Weinberg, 126; 179; Marc Simpson, Uncanny Spectacle: The Public Career of the Young John Singer Sargent (New Haven: Yale University Press; Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1997), 119. See also Mahon and Centeno, 123–24; Ormond and Kilmurray, 113–17.

[54] See the quotation on Carolus-Duran in Charteris, 60. “Nous espérons bien voir figurer au Salon prochain cette œuvre, qu’on dit remarquable.” “Nos Echos,” Le Gaulois, January 11, 1884, 2.

[55] Fairbrother documented the repainting of the strap into an upright position in “The Shock of John Singer Sargent’s Madame Gautreau,” 90–97. See also Henry Fouquier, “Le Salon de 1884,” Gil Blas, May 1, 1884, 3.

[56] Justine De Young, “1884—John Singer Sargent, Madame X (Virginie Gautreau),” Fashion History Timeline, March 24, 2017, http://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1884-sargent-madame-x/. The dress by Rebours is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2009.300.3304a–c). See also Justine de Young, “Women in Black: Fashion, Modernity and Modernism in Paris, 1860–1890” (PhD diss., Northwestern University, 2009), 310–21.

[57] See Michele Majer, ed., Staging Fashion, 1880–1920: Jane Hading, Lily Elsie, Billie Burke (New York: Bard Graduate Center, 2012), cats. 14, 15.

[58] “La Belle Americaine,” New York Herald, March 30, 1880.

[59] See, for example, “New Gowns in Paris,” Daily Evening Bulletin (San Francisco), April 15, 1882, n.p.; Comtesse de Champdoce, “Paris,” Vogue, April 5, 1894, 2; Intime [pseud.], “A Parisian Prince of Dress,” Lady’s Realm: An Illustrated Monthly Magazine 9, November 1900–April 1901, 21–26.

[60] L. Bourne, Le Panthéon de l’industrie: Journal Hebdomadaire Illustré, May 14, 1882, 145–46. Auguste Poussineau became a successful real estate developer in Dinard. The present author is conducting extensive research on the maison Félix.

[61] Emile Martin Poussineau, unpublished memoir, collection of Martin Chatillon cited by Marie-France Faudi, email message to author, August 24, 2017. Various sources, including garments in museum collections, magazine and newspaper articles, theater records, and individual archives, letters, and autobiographies contribute to a working list of clients in Europe and the United States.

[62] “Tribunaux,” Le Temps, February 11, 1884; Emma Bullet, “Her Toilets: Mrs. Langtry’s Preparations in Paris for America,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 2, 1886, 4; “New Gowns in Paris,” n.p.; “Gowns and Headgear: The Newest Devices of the Modistes Who Set the Fashion,” New York Times, April 15, 1888; “Gowns On and Off the Stage,” New York Times, February 9, 1890, 14; “Stage and Other Gowns,” New York Times, April 27, 1890, 16; D. F., “The Fashions for Winter,” New York Times, November 2, 1891, 9.

[63] Emma Bullet, “Her Toilets,” 4.

[64] “New Gowns in Paris,” n.p.

[65] Bourne, 145–46.

[66] “New French Gowns,” New York Times, November 11, 1888, 2; “La Toilette féminine en 1897,” Le Figaro, supplément exceptionnel, August 19, 1897, 1; Bourne, 145–46; unpublished memoir by Emile Martin Poussineau in the possession of the family, France. The business appears in Annuaire-almanach du commerce, de l’industrie, de la magistrature et de l’administration as early as 1857 as “coiffeur,” at 15, rue Faubourg-Honoré, and continues semi-consistently through 1901.

[67] Davis and Oustinoff suggest that a notation in the Gautreau ledger in the Archives Municipales, Saint-Malo, France, may refer to the dress. It is listed under “Toilette de Madame” for the purchase of “satin noir p/robes” at 212,60 francs (no date given). Davis and Oustinoff, 125n14, 116–25. The Gautreau family home in Paramé was located six miles from the Poussineau home in Dinard, and it is likely that the families knew one another. I thank Eric Poussineau, great-grandson of Émile Martin Poussineau, for his assistance in confirming the documented parts of the history of the Poussineau family. For Félix’s preferred slim silhouette, see “The Ladies’ Column,” Manchester Times, January 14, 1882, n.p. Sargent’s frequent trips to Brittany during the 1880s suggest that he, too, may have known the Poussineau family. See, for example, Letter from Sargent to Emma Marie Allouard-Jouan, Summer 1883, SC.SargentArchive.7.5, The John Singer Sargent Archive, The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in which he wrote, “De Paramé à Dinard il n’y a qu’une demi heure de sorti que vous me verrez souvent. Et puis vous devez aller voir les Gautreau.” (From Paramé to Dinard is only a half-hour’s trip so you will see me frequently. And then you must go see the Gautreaus.)

[68] Koda, 11; see also 89.

[69] See also Antonio Canova, Venus (Venus Italica), 1810, Palazzo Pitti, Florence.

[70] Koda, 111.

[71] For more on the circulation of images of actresses via cartes-de-visites, cabinet cards, and postcards, see Majer, ed., 31–34.

[72] See, for example, Alma, Mary Anderson as Parthenia, 1883, ink on board, Victoria and Albert Museum, London (S.896-2011).

[73] Le Figaro remarked upon her “all black ball toilette” that contrasted with the “whiteness of the flesh” and the diamonds in her hair. “Sargent,” Le Figaro, March 15, 1884, 2.

[74] Ormond and Kilmurray identified the winged sirens; Ormond and Kilmurray, 114.

[75] Gautier, 1.

[76] Brownell, 494. Italics in the original.

[77] “Les cheveaux sont teints, les chairs fardées,” Paul Arène, “Promenade au Salon,” La Nouvelle Revue 23, no. 3, June 1, 1884, 603.

[78] Marie Bashkirtseff, The Last Confessions of Marie Bashkirtseff and Her Correspondence with Guy de Maupassant (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1901), 87.

[79] “Eccentricities of French Art,” The Art Amateur 11, no. 3, August 1884, 52.

[80] A similar derision was expressed toward live fashion models (called “mannequins”) at the time, which were viewed as uncanny “doubles” of the live person wearing the clothes. Caroline Evans, The Mechanical Smile: Modernism and the First Fashion Shows in France and America 1900–1929 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 20.

[81] William Sharp, “The Paris Salon,” Art Journal (London), 1884, 1780. See also “The Paris Salon,” The Saturday Review, June 7, 1884, 745.

[82] Sidlauskas, 23–25. See also Syme, 141–43.

[83] Edward Simmons, From Seven to Seventy; Memories of a Painter and a Yankee (New York: Harper, 1922), 127.

[84] “peintres ne doivent pas traduire au pied de la lettre ces fleurs de rhétorique.” Claudius Lavergne, “Beaux-Arts, Exposition annuelle de 1884,” L’Univers, July 1, 1884, 1.

[85] “Mr Sargent a fait un chef d’œuvre du portrait, je tiens à vous l’écrire car je suis sûre qu’il ne vous le dira pas.” Letter from Sargent and Gautreau to Emma Marie Allouard-Jouan, Summer 1883, SC.SargentArchive.1, The John Singer Sargent Archive, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

[86] For the reaction of Marie Virginie de Ternant, Gautreau’s mother, see Letter from Ralph Curtis to Daniel Sargent Curtis and Ariana Wormeley Curtis, 1884, box 1, folder 12, David McKibbin Collection on John Singer Sargent, Boston Athenaeum, Boston. Reprinted in Charteris, 61–62; Ormond and Kilmurray, 113–14. For Sargent’s response, see Fairbrother, “The Shock of John Singer Sargent’s Madame Gautreau,” 91; Fairbrother, John Singer Sargent, 46; Herdrich and Weinberg, 128.

[87] “A Paris depuis un an ou deux j’ai si peu de commandes, l’effet du désastre Gautreau probablement.” Letter from Sargent to Emma Marie Allouard-Jouan, [1885?], SC.SargentArchive.7.8, The John Singer Sargent Archive, The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

[88] Fairbrother, “The Shock of John Singer Sargent’s Madame Gautreau,” 90; Simpson, 121; Ormond and Kilmurray, 114; Fairbrother, John Singer Sargent: The Sensualist, 81. At this time Sargent changed the title to Madame X.

[89] “The Beauty of Mme Ferry: Paris Letter to the London Truth,” New York Times, February 17, 1885, 3.

[90] Exaggerated accounts of Gautreau’s later life stem from Pringué’s reminiscences of talking with Gautreau’s daughter, Louise Emilie Virginie Gautreau Jallu (b. 1879–ca. 1913), but are not borne out by documented evidence. Pringué, 213–14. See also Olson, 101–2. The quotation about her theatrical debut is in “Mme. Gauthereau’s New Step,” New York Times, March 27, 1887, 4; see also “People and Events,” The Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago), July 19, 1887, 4; “Carnet Mondain,” Gil Blas, June 1, 1900, 2, 1; and Sherard, 613.