The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Van Gogh & Japan

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

March 23–June 24, 2018

While scholars are well aware of the impact that Japanese art and culture had on Vincent van Gogh, the general public has perhaps only a passing awareness. The goal of this exhibition was to redress this condition by vividly illustrating the effects of exposure to subject matter, media, stylistic innovations, and contextual information from Japan that consistently intermingled with van Gogh’s artistic and social practices. While the general public is the focus, scholars and museum professionals still benefit from fine rarely seen gems, smart integration of didactic materials, and inspiring exhibition design.

The museum employed theater designers Nathalie Crinière and Tomoko Nikishi of Agènce NC Scénographie to great effect, as the idea of the floating world was subtly recreated visually on two of the three floors occupied by the exhibition. Floating platforms, layered textures and materials, and soft curves to contrast hard lines and angles create a zen-like mood in the first space. Scrolls of textured material float behind glass panels on which prints were hung; the mix of materials evokes the spatial structures of the prints themselves (fig. 1). This approach also mediated the disparity between the height of the room and the small size of the prints, which makes the space seem more intimate and compensates for the size disparity with van Gogh’s oils, which were hung on shorter walls (fig. 2). The exhibition strategy provided visual pauses that reinforced the meditative atmosphere, for instance the entire back of one dais was left completely empty as a counterpoint to tightly spaced landscape paintings.

More subtle, but no less significant, was the use of wall color to symbolize the psychological effect of van Gogh’s contact with Japan chronologically—the walls on the first floor began with a pale blue-green wash that shifts to a warm pink as the artist begins to internalize the principles gleaned from the study of Japanese prints (figs. 3, 4). The walls of the main gallery on the second floor began with a yellow tint and then shifted to a soft gray as the exhibition ended. Also, on the second floor was a comparatively narrow space with dark brown walls and a long dramatic approach to a series of self-portraits hung on walls that visually mimicked the appearance of a Japanese folding screen (fig. 5). The designers worked carefully to create maximum contrast in this area; viewers moved through the darker space first, but can simultaneously glimpse the bright color on the other side through a series of perforated barriers (fig. 6). The purpose of the brighter wall color is underscored with a quote from Théo van Gogh reproduced in the center of the space: “And we wouldn’t be able to study Japanese art, it seems to me, without becoming much happier and more cheerful, and it makes us return to nature despite our education and our work in a world of convention” (September 23/24, 1888).[1] A small label outside the second-floor gallery acknowledges that the Dutch paint manufacturer, Sikkens, provided paint through its parent company Akzo Nobel, who credit van Gogh’s use of color as a continuing source of inspiration.

The most overtly dramatic element of the exhibition appeared in the stairwell between the first and second floors (figs. 7, 8). Here an anonymously produced color woodcut and crépon (crinkled paper), Two Manzai Dancers and Kite Flying Women and Children at the New Year (1875) was reproduced in a gigantic format to maintain exhibition flow, build excitement, and create atmosphere. The colors of this particular print provided brighter versions of the wall colors throughout the exhibition. The mix of curves and straight lines both correspond to, and modulate, the lines of the staircase and architecture. The mixed medium of the original is also significant because van Gogh was specifically inspired by stylistic effects produced by both techniques. However, the work was not identified with a wall label directing viewers to the second floor to find the original among dozens of other works; as a result the average viewer likely missed its significance.

Each floor of the exhibition had to contend with challenges created by the shape of the building. Niches and partial walls were added to provide visual interest and directional flow, but as each space became smaller while the number of artworks increased, viewers felt a lack of physical and visual breathing space on the second floor in comparison to the first (figs. 9, 10). This problem could only have been solved by reducing the total number of works featured in the exhibition, perhaps a few from the museum’s collection could have remained in the other galleries.

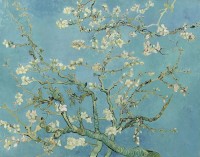

Curators Nienke Bakker and Louis van Tilborg, in cooperation with the Japanese print expert Chris Uhlenbeck who rechecked and expanded information on all of the included prints, shaped the narrative of the exhibition, which, other than the issue of crowding mentioned above, is largely successful. The first and second floors each concluded with a powerful statement piece: Almond Blossoms, (1890; figs. 11, 12); Rain Auvers (1890), respectively. The third floor contained only prints from Vincent’s personal collection, some of which he purchased from Siegfried Bing in the winter of 1886–87 with the intent to resell them for a profit; others he studied repeatedly in different contexts, as he carried them with him during his travels. Shallow lit-from-behind cases practically disappeared, allowing the artfully arranged prints to suggest the way the artist likely displayed them in his atelier and personal spaces (fig. 13). Direct comparisons to van Gogh’s paintings and thematic divisions were avoided here—rather the prints created a strong visual impact due to their sheer number, which effectively shifts the emphasis to formal qualities. Works by Honoré Daumier and Eugène Delacroix were included to underscore how Vincent considered prints in general to be an important, albeit economical, source of inspiration. Brighter and better preserved exemplaries from other collections were inserted throughout the rest of the exhibition; those on the third floor showed evidence of wear and contained pin holes at the edges (fig. 14). The curators rightly emphasized that these imperfections are, in fact, important evidence supporting the central assertion of the exhibition.

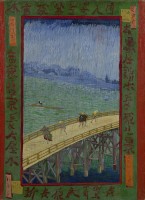

One-to-one comparisons were rare in the show, with the notable exception of the entry wall where two of van Gogh’s direct copies, Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige) (1887) and Flowering Plum Orchard (after Hiroshige) (1887) were displayed alongside the prints that inspired them (figs. 15, 16). From here viewers were exposed to a careful selection of prints demonstrating typical themes and processes, especially the crépon technique that Vincent attempted to replicate in some of his oils. A small but powerfully designed corner in the first gallery presented Paris as the first point of contact and provided an important contrast—Japonisme could be described as a general craze, but van Gogh’s approach was more intimate—the curators quickly counter with works emphasizing sophisticated technical detail, such as a fine panel inlaid with ivory borrowed from Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, Leiden (figs. 17, 18). The sources for van Gogh’s third direct copy were spatially separated from the oil painting, Courtesan (after Eisen) (1887). The 1886 issue of Paris Illustré, titled Le Japon and copied by van Gogh, was in a case near the beginning of the exhibition (the artist’s preparatory drawings for the copies appeared only in the exhibition catalogue) (fig. 19). Instead, directly opposite the painting are a trio of stunning pillar prints by Keisai Eisen and Katsukawa Shunsen with similar compositions (fig. 20).

Four landscapes created by van Gogh during the winter 1888 to spring 1889 set the stage for a section of the exhibition titled “Southern France as Japan,” where the warm wall color suggested the new energy and bright color the artist discovered in Arles. These were met by a large selection of Japanese prints, including Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s triptych, Famous Flowers of Horikiri: The Irises of Edo (1852) to underscore van Gogh’s characterization of his field of irises as “A Japanese Dream” (figs. 21, 22).

A video produced by Creative Beards, based on the concept of Van Gogh Museum Senior Educator Jolein van Kregten, was a critical didactic tool. It was strategically placed within the gallery rather than in a separate room and displayed on a monitor approximately the same size as van Gogh’s landscape paintings (fig. 23). Vivid animations easily caught and held viewers’ attention as the video demonstrated the Japanese principles using works displayed throughout the exhibition. The video poses the question “What did van Gogh learn from Japanese prints” and then demonstrates bright flat areas of color, bold contour lines, prominent diagonals, subjects cut off at the edges, high/absent horizon lines, and zoomed-in details. While the text in the video could be better written, and the works in the video are never specifically identified, the animations themselves are stunning. Most sequences begin with a Japanese print, employing cover overlays to highlight a particular principle, then shows that same principle at play in one of van Gogh’s paintings. Especially effective was the use of animation to show to what degree perspective was “tilted” in Vincent’s landscapes. The video ends with Self Portrait with Bandaged Ear (1889), isolating the Japanese print in the background of that painting and then building in a collage of other works that gave a clever preview of the second and third floors of the exhibition.

The rest of the space on the first floor contains a large number of landscapes, demonstrating increasingly agitated brushstrokes followed by examples of dramatic cropping. Cases contain flower and insect works by Utamaro, Bumpo and Hokusai, a wonderful van Gogh drawing Three Cicadas (1889), and Siegfried Bing’s Study of Grass (1845) published in Le Japon Artistique (1888) (fig. 24). There is an important message here that Vincent could choose to see the world as a “single blade of grass,” but it was difficult for the small works in the cases to compete with large oils in the same space (fig. 25). The curators wisely included van Gogh quotes on otherwise empty hanging scrolls to try to get this point across. Near the end of the first floor two quotes written just days apart were juxtaposed (fig. 26). On June 5, 1888 Vincent emphasized feeling in a letter to Théo: “After some time your vision changes, you see with a more Japanese eye; you feel color differently.”[2] Just two days later he wrote to Emile Bernard emphasizing technical aspects: “The Japanese disregards reflection, placing his solid tints one beside the other—characteristic lines naively marking off movements or shapes” (June 7, 1888).[3] While there is a danger of isolating such short quotes from the larger context of van Gogh’s considerable volume of letters, it was nonetheless effective in demonstrating how the artist tailored his written communications based on his intended audience. Earlier in the exhibition was an excerpt from a letter to his sister Willemien: “I’m always saying to myself that I’m in Japan here. That as a result I only have to open my eyes and paint what is right in front of me, what makes an impression on me” (September 9 and 14, 1888).[4]

Throughout the exhibition a number of loans filled in gaps in the Van Gogh Museum collection. Nowhere was this more evident than on the second floor where Self Portrait as a Monk (1888, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Cambridge, MA) was critical to demonstrate deeper and more communal inspirations Vincent derived from study of Japan (fig. 27). Self Portrait as a Monk, after all, was originally traded with Paul Gauguin, with the hope that Vincent’s understanding of Japanese artists as humble artisans living in harmony might rub off on his compatriots and result in successful creation of an artist’s colony in Arles. Other loans important to the shaping of the exhibition’s larger narrative included Woman Rocking Cradle (Augustine Roulin) (1889, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago), De Arlesienne (Marie Ginoux) (1888, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and Rain Auvers (1890, National Museum, Wales), which, paired with rain prints by Hiroshige that van Gogh saw in a Paris exhibition in 1890, provided a stunning conclusion to the exhibition’s second floor (figs. 28, 29). A number of other loans, while neither as well-known nor critical to the show’s narrative nevertheless showed how influences such as a trip to the Mediterranean (Blue Gloves and a Basket of Oranges and Lemons [1889, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC]) and the cloisonism of Toulouse-Lautrec (Dance Hall in Arles [1888, Musée d’Orsay, Paris]) interacted with van Gogh’s appreciation of Japanese art.

Two Japanese Crépons (ca. 1848–90, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) is a piece fabricated by Paul Gachet, Jr., after Vincent’s death (fig. 30). Color woodcuts from the artist’s collection were cut out and pasted on a gold background and an inscription was added in Japanese stating that these prints hung in the artist’s room in Auvers-sur-Oise. Additional prints from Vincent’s collection were compiled into an album titled “Memories of van Gogh.” These re-contextualizations by a third party, for a not clearly articulated purpose, are the earliest examples of the creation of a narrative from van Gogh’s exposure to Japan. They were intriguing additions to the exhibition that remain under-investigated by scholars, but, like many of the Japanese prints on the second floor by Kunichika, Utamaro, and Toyokuni, they suffered from display in a space crowded with visitors jostling for position in front of the oil paintings. Only Utagawa Hiroshige’s Naruto Whirlpoolin Awa Province (1855) and Katsushika Hokusai’s work known as the Great Wave (ca. 1830–32) found positions out of the fray (fig. 31).

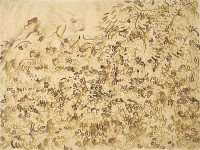

Works by Fujimoto Tesseki, used to demonstrate van Gogh’s attempt to match calligraphic flow of lines, dots, short dashes, and hatching, are large enough to compete visually in the space (fig. 32). These framed the entrance to a room dedicated almost exclusively to van Gogh’s drawings. Two particularly unforgettable works were Mowed Lawn with Weeping Willow (1888) and La Crau seen from Montmajour (1888), which van Gogh claimed were among drawings “which don’t look Japanese and which are perhaps more so than others, in fact”[5] (fig. 33). Despite this assertion, these drawings demonstrated the varied use of lines taken from Japanese prints and key resources such as Hokusai’s Sketches (1814–19) and Kawamura Bunpō’s Instructions in Chinese Painting (1811), both of which are displayed in the space. Wild Vegetation (1889) might be more “modern” than any of van Gogh’s other drawings or paintings for that matter—the repeating forms are stunningly similar to Jean Dubuffet’s Hourloupe paintings from the 1960s (fig. 34).

Van Gogh was no average collector and the act of looking at Japanese prints was part of a more comprehensive philosophy. While he initially thought the prints would be a source of income, they were no mere curiosity for him. Rather he used them, by copying them, remixing them with other elements, and taking them with him when he traveled (figs. 35, 36). Most importantly, he studied them repeatedly over a long period of time. The collecting created a mindset that the exhibition attempted to recreate for the viewer. A second emphasis of the exhibition, alluded to throughout, but most clearly articulated on the second floor, was van Gogh’s search within the prints, and the context in which they were created, for what he believed was not only a more decorative and “modern” art, but also a different, more collaborative way of working stimulated by the sharing of prints. Other possible narratives were left up to the viewers—there is no mention of color theory, for instance, and the poems usually included with Japanese prints are largely unaddressed—the exhibition successfully challenges the audience to draw some conclusions on their own.

Elizabeth Mix

Professor Emerita, Butler University

emix[at]butler.edu

[1] Letter 686 Br. 1990: 690 | CL: 542 From: Vincent van Gogh To: Theo van Gogh

Date: Arles, Sunday, 23 or Monday, 24 September 1888

Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, inv. nos. b586 a-b V/1962

http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let686/letter.html, accessed June 20, 2018.

[2] Letter 620 Br. 1990: 623 | CL: 500 From: Vincent van Gogh To: Theo van Gogh

Date: Arles, on or about Tuesday, 5 June 1888

Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, inv. no. b541 V/1962

http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let620/letter.html, accessed June 20, 2018.

[3] Letter 622 Br. 1990: 625 | CL: B6 From: Vincent van Gogh To: Emile Bernard

Date: Arles, on or about Thursday, 7 June 1888

New York, Thaw Collection, The Morgan Library & Museum

http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let622/letter.html, accessed June 20, 2018.

[4] Letter 678 Br. 1990: 681 | CL: W7 From: Vincent van Gogh To: Willemien van Gogh

Date: Arles, Sunday, 9 and about Friday, 14 September 1888

Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, inv. nos. b707 a-b V/1962

http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let678/letter.html, accessed June 20, 2018.

[5] Letter 639 Br. 1990: 643 | CL: 509 From: Vincent van Gogh To: Theo van Gogh

Date: Arles, on or about Friday, 13 July 1888

Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, inv. no. b550 V/1962

http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let639/letter.html#translation, accessed June 20, 2018.