The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Goupil & Cie, originally established as Rittner & Goupil[1] in Paris in 1829, was one of the most prominent print and art dealers of the nineteenth century. Initially, the activities of the firm consisted of reproducing, publishing, and selling prints in Paris. Later, the directors diversified to also deal in original artworks. Goupil’s operations coincided with a turning point in the history of art, which marked the shift from traditional patronage of the arts—church, royalty, aristocracy, and state—to a market system made possible by an increasingly rich and powerful bourgeoisie.[2] Goupil was one of the first dealers to engage in such a system, which in turn facilitated its ambitions of internationalization. After expanding first to London in 1842, the firm opened a New York branch in 1848 as Goupil & Co. and went on to develop an extensive network of branches and partnerships across Europe, the United States, the Ottoman Empire, and as far as Australia. While international expansion had a number of advantages—including higher growth potential by accessing a larger pool of clients—uncertain economic outlook, as well as cultural and regulatory differences, created a challenging scenario. Using Goupil’s New York branch as a case study, this article will investigate the strategy Goupil & Cie and its associates implemented to successfully balance the perks and perils of operating a business remotely.

As an addition to the numerous articles by DeCourcy E. McIntosh, which revealed for the first time the influence of the French dealer on the American market,[3] this paper will explore in detail the obstacles to, and uncertainties in, creating and keeping a presence in the art market across the Atlantic in the mid-nineteenth century. Since 2012, with the acquisition by the Getty Research Institute of the archival material of the Knoedler Gallery, successors of Goupil & Co. in New York in 1857, it has now become possible to also reconsider some aspects of a business relationship that dominated the market for European art in America for half a century and secured the legacy of Goupil in this country.[4]

The Early Years of Goupil in New York

In February 1848, William Schaus (1821–92) became the gallery’s first director in New York, opening Goupil, Vibert & Co. at 289 Broadway (fig. 1). A legal document pertaining to the 1855 liquidation of the Parisian headquarters, which followed insolvable divergences between Adolphe Goupil (1806–93) and Alfred Mainguet (fl. 1846–56) business partners since 1846, explains that the New York gallery consisted of “a whole house, entirely rented for another 8 years; for a price of 13,000 francs per year.”[5] Prior to the 1848 opening, very little European art had entered the embryonic American art market, and very few dealers had dared to establish a gallery, as Adolphe Goupil explains: “Until 1848, print exports to the United States were almost null, [and] painting exports did not exist.”[6] According to the 1860 census, New York, a city of 515,000 residents, was only beginning to approach its potential, while Paris and London had populations at least double New York’s size (over 1 and 2 million, respectively). Goupil, Vibert & Co. recognized, however, that the American art market had tremendous potential, and its owners knew there was little competition.[7] Furthermore, New York’s geographical location made the city one of the country’s main ports of entry and economic centers, thus a rich soil for a dynamic arts scene.[8]

Note: Use the tools available on your device to move and zoom.

Fig. 1, A Panoramic View of Broadway, New York City, Commencing at the Astor House, showing Goupil & Co. (after its change in name in 1850) at 289 Broadway, 1854. Wood engraving. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library, New York. Available from: The New York Public Library Digital Collections, digitalcollections.nypl.org. The building number for Goupil & Co. appears incorrectly as 288 in the wood engraving.

In his article on the history of picture dealing in America, published in the New York Times in 1897, C. L. Beaumont[9] situates the inception of an interest in art in New York in the early years of the 19th century, when the principal picture dealer in the city, Michael Paff, a German immigrant, opened his doors, initially specializing in musical instruments and then in art in the 1810s.[10] Beaumont wrote, “A person known as ‘old Paff’ sold more pictures than any other dealer; he was an eccentric man, and his place of business was where the Astor house now stands. Paff, we are told, always had something new in the old line.” He continued, “Michael Paff would wash, scrape, study and ponder over an old picture; would sit up nights with it consulting books, and when he had made a discovery, his enthusiasm carried him off the earth.”[11] Paff introduced connoisseurship to America, yet while his personality and enthusiasm made him a respected dealer, his insouciant, even cavalier manner of conducting business allowed numerous paintings of doubtful attribution or condition to enter private collections, which discredited paintings from Europe and particularly the old masters. Collectors, instead, turned their attention to fostering local living artists,[12] and institutions promoting American art emerged, including the National Academy of Design in 1825 and the Apollo Gallery in 1838, which became the American Art-Union the following year.[13] Paff’s nonchalance compromised subsequent commercial attempts to introduce European art in New York: any dealer from the Continent had to demonstrate his trustworthiness and professionalism while showing respect for the nation in its quest for identity and growth. Thus, the decision to open a gallery in New York was material proof of Adolphe Goupil’s visionary and courageous mission to promote European art worldwide,[14] but this risky project could jeopardize his whole business if he failed at deciphering these specificities of the American art market.

In the 1840s, Goupil & Cie, headquartered in Paris, under the leadership of Adolphe Goupil and Théodore Vibert (1816–50), was a young entity that had not yet achieved financial stability. However, Goupil and Vibert, worried about the long-term viability of their business, already weakened by Europe’s economic turmoil, sought to develop a new market overseas,[15] which was now possible thanks to advances in transatlantic routes. Thus, in 1847, Goupil and Vibert sent to New York William Schaus, a German émigré working for the Paris offices, to prospect the local market as a destination for their prints. Their competitive advantage laid in their ability to supply the finest images to collectors, which would prove key to the gallery’s success abroad. In fact, Goupil and Vibert already represented Paul Delaroche (1797–1856), Horace Vernet (1789–1863) and Ary Scheffer (1795–1858), three of the most famous French artists at the time. Their having been elected honorary members of the National Academy of Design facilitated Goupil, Vibert & Co.’s entrance into the American art market.[16]

Goupil, Vibert & Co., just as the enterprise had done in Paris and in London, chose to establish the New York gallery on a bustling thoroughfare of the city, 289 Broadway, thereby benefitting from the businessmen, dealers, collectors, and flâneurs heading toward the business district, and the shoppers heading to Alexander Turney Stewart’s famous department store across the street. For Régis de Trobriand, a French expatriate in New York who fought during the Civil War, “Broadway is not only the most elegant street, the most lively, the most aristocratic, and often the dirtiest: it is also the most entertaining, the richest in curiosities of all varieties.”[17]

In the beginning, the New York branch, like the London branch, was intended to be a wholesale and not a retail gallery, selling mainly to professionals. The New York gallery was at the forefront of Goupil & Cie’s efforts to diversify its product line. For example, while the London branch focused exclusively on prints, the New York shop carried artists’ supplies as well as prints.[18] In addition, Goupil & Cie tried to make a name for itself and the art it represented by publishing numerous self-inflating advertisements in local journals. It also strove to obtain high media coverage for each of its events, as it did in 1848, just a few months after it opened, when it held its first exhibition of paintings. This strategy was, however, slow to prove its effectiveness. As Mainguet explained, although “in 1848, the sales were 119,651 francs, [and] in 1849, 188,601,” these earnings fell short of providing a return on the investment.[19]

Furthermore, a major obstacle faced by Goupil & Cie was Schaus’s personality and management style, which created problems with employees as well as clients. First Vibert and then Mainguet went to New York to straighten out the situation. In a letter dated November 7, 1850, Adolphe Goupil wrote to Mainguet: “I have not been surprised to read what you say about Schaus, I can’t but repeat what I said in my last letter: you had a very good idea to go to the United States. . . . It is important for me to bring order and light on everything. You are there, so we are relieved. You are going to have a hard time, I know, at subduing Schaus’s character, who believes he is a superior man.”[20] However, Mainguet’s visit to New York only aggravated a tense situation, and after nine months no solution was found. In the end, the problem was solved only when in 1852 Schaus resigned and opened his own gallery in New York.[21]

Léon Goupil (1830–55), Adolphe’s eldest son, replaced Schaus as the New York gallery’s managing director. Between 1853 and 1854, Léon persuaded his father to invest more than 150,000 francs in the premises, reorganizing the space:

On the first floor, are the wholesale store for the prints and the color material, and the painting gallery; on the upper floors, 3rd and 4th, are the workshops and lodgings for the manager and the main employees, who pay rent; in the cellars (basement), the storehouse; in a detached house at the back and separated by a small courtyard, are the workshops for the carpenters, the color grinders, etc.[22]

Most significantly, in 1854, under Léon Goupil’s leadership, Goupil & Cie opened a retail store, “on the ground floor, a vast store of a hundred feet long and twenty-five feet wide; it is the retail store for framed or unframed prints, paintings, colors and drawing material, glass, etc.”[23] With the opening of the retail store for prints and artists’ supplies, the New York gallery’s earnings rose to 569,000 francs in 1854.[24] These additional investments and the high volume of European prints and paintings now flocking to New York placed Goupil & Co. at the forefront of American art dealers.

Although transatlantic shipping had improved greatly in recent years, the endeavor nonetheless imposed considerable costs upon Goupil & Cie. Shipping required both proper packing in special crates and expensive insurance policies. In 1849, for example, shipping three paintings from Le Havre to New York cost 647.90 francs.[25] Proper packing, moreover, could not guarantee protection of the artworks against unpredictable travel conditions. Goupil’s stock books[26] show that between 1846 and 1884, 60 paintings were declared lost or damaged during transport. For example, on November 23, 1853, the Humboldt, a steamer carrying four paintings belonging to the French art dealer, departed from Le Havre and while en route to New York was caught in a terrible storm.[27] The losses were significant: one passenger died and three of the four paintings owned by Goupil were declared a total loss.[28] Only La convalescence, by Ferdinand Waldmüller, was saved and added to the New York inventory.[29]

After artworks had arrived safely in the port of New York, they had to be cleared by customs. Ad valorem duties in 1846 on imported paintings intended to be sold commercially were 20 percent, on engravings, 10 percent.[30] Goupil & Cie, in order to remain affordable, often reduced the price of its merchandise.[31] In 1854, the French dealer lowered the price of art supplies by 30 percent and of paintings by 40 percent.[32]

Tariffs were a major obstacle for European dealers seeking to do business abroad. In a letter of 1857 to William Rosseti, the independent British dealer Ernest Gambart explained that the recent elimination of duty on all imported paintings permitted him, for the first time, to organize exhibitions in America. “I acknowledge having for a long time,” he wrote, “entertained the notion of an exhibition of British works in New York, but it is only since the reduction of the tariff that I have taken any decided steps in the matter.”[33] Goupil & Cie learned to circumvent these charges by using loopholes in the American legal system well before 1857. For example, back in 1846, imported artworks were exempt from duties if they were brought in for noncommercial purposes and remained in the United States for less than six months.[34] This was probably one of the motivating factors behind Goupil’s creation of the short-lived International Art-Union in 1848 (fig. 2).

The International Art-Union was a type of nonprofit organization modeled on the art union system that provided prints to subscribing members. Officially founded to promote the fine arts, the International Art-Union had “for its principal objects the introduction into the United States of the Chefs d’œuvres of Modern European Art; the gratuitous distribution of a large number of them, annually, among our citizens; and the sending annually at least one American Artist, to study in the best Schools of Europe, at the expense of the Institution.”[35] Regardless of other motivations, Goupil and Vibert’s official statement clearly expressed their genuine wish to contribute to the local community’s advancements in the arts. Their new pursuit, however, raised the wrath and jealousy of the American Art-Union (AAU), and a fierce battle broke out between the two institutions. The AAU reproached the International Art-Union as merely a cover for profit seeking. The AAU even went so far as to approach a customs officer to demand not only that he seize a painting by Victor François Eloi Biennourry (1823–93) that the AAU judged immoral,[36] but that he also require the International Art-Union to pay 2,000 dollars of taxes on the artworks it had already imported—20 percent on all paintings and 10 percent on all engravings—claiming they were merely objects of merchandise.[37] These actions of the AAU brought discredit to the International Art-Union and eventually led to its liquidation in 1850. Goupil and Vibert reorganized and instead of having their own exhibitions began collaborating with other European dealers, as in 1857 and 1859, when they supplied Gambart’s touring exhibitions with some of their paintings.[38] In addition to taking advantage of relaxed import taxes, these exhibits allowed the participating dealer to promote the prints made of the paintings on display. As Adolphe Goupil plainly stated in 1856, “What did we wish to do by establishing a house in New York? Principally, and above all, to dispose of the prints of our publication. . . . We said to ourselves that in spite of the expenses, the disposition of our products would still give a profit to the Paris house.”[39] As a matter of fact, the New York branch was also a means to compensate for the declining art market in Europe. During the late 1840s, Europe suffered from an economic crisis that affected Goupil’s main clients: bankers and industrialists. In a letter dated 1848, the painter Paul Delaroche could not but concur: “The business of art, like the arts has been lost in France for a long time.”[40] Adolphe Goupil’s private correspondence differs from his official discourse with regard to the opening of a branch in New York. In France’s political turmoil, it was also important for Goupil to present himself as a patriot whose overseas ambitions aimed to help European artists find more patrons. When the French government granted him the Légion d’honneur in 1877 for his efforts to promote French art abroad,[41] it confirmed the image Goupil had long sought to represent: an altruistic and heroic supporter of the arts.[42]

Regardless of Goupil’s underlying reasons for opening the New York branch, running an overseas gallery was difficult and very risky. Both Théodore Vibert and Léon Goupil died young. In fact, Adolphe Goupil blamed their deaths on oceanic travels and insalubrious living conditions in New York. For example, his application for the 1855 international exhibition includes the following: “Two partners of the ‘maison,’ Mr. Vibert and Mr. Goupil’s eldest son, successively in charge of the organization and management of the American branch, succumbed, one in 1850 at the age of thirty-four, and the other, in 1855 at the age of twenty-five, to diseases caused by unrelenting work and long and difficult trips in an unsanitary climate.”[43] While it may never be known what caused the deaths of Vibert and Léon Goupil, it must be recognized that crossing the Atlantic Ocean remained a perilous two-week venture. After almost ten years in America, disillusioned with his staff, tired of the difficulties in transporting the works, and unable to identify and adapt to the cultural differences between Europeans and Americans, as epitomized by his conflict with the AAU, Adolphe Goupil questioned his New York branch’s raison d’être. On October 4, 1855, he confided in his friend Michael Knoedler (1823–78), the New York branch’s new manager: “For a long time I have been meaning to write to you to talk with you of plans, which have been suggested to me by the misfortune which has smitten me in what I held dearest in the world. . . . Providence did not will that the dream of my whole life should be realized.”[44] It became clear he had to reevaluate his strategy.

Knoedler & Co., Successor to Goupil New York

In 1856, the contract between Adolphe Goupil and Alfred Mainguet came to an end, and the Paris-headquartered firm went into judicial liquidation due to the protagonists’ unwillingness to renew it.[45] Goupil decided to offer Michael Knoedler and two other employees, Kroll and Muston, a partnership if they were to buy out Mainguet’s share: “Whatever may happen, be assured it would be a real satisfaction for me—my son having been taken away—to have at my side to replace him the three men I esteem and like the best of those who surround me.”[46] Michael Knoedler, who had worked for Goupil & Cie in Paris for eight years before he was sent to New York in 1852,[47] refused. Instead, he persuaded Goupil to sell him the entire New York business for 300,000 francs, and Goupil & Co. was renamed “Goupil & Co., M. Knoedler Successor.”[48] The sale agreement, signed in Paris on March 23, 1857,[49] also included the assignment of the lease and acquisition of the existing equipment, the furniture, and the clientele. The existing stock of prints, paintings, and art supplies, as fixed at the December 31, 1856 inventory, remained in Goupil & Cie’s possession but were consigned to Knoedler. Until December 31, 1863, Goupil would commit to consign both prints published by his firm and paintings they both deemed suitable for the American market. The agreement also specified that Knoedler would cover all shipping expenses and import duties at his own risk; that Goupil would determine the prices at which Knoedler was to sell the paintings; Knoedler would get a share of the net profits; and Goupil & Cie remained responsible for outstanding debts.[50]

Because Knoedler kept detailed records[51] we know that transportation costs and shipping risks remained as central for Knoedler & Co. as they had been for Goupil & Cie. For example, in April 1874, the Europe was transporting paintings and prints valued at 51,428 francs that Goupil had sent to Knoedler;[52] however, owing to water leakage, the boat and its shipment were abandoned at sea. No mention of this shipwreck appears in Goupil & Cie’s stock books, perhaps because Knoedler remained fully responsible for any costs relating to the transport of artworks, including insurance, even after their original contract expired on December 31, 1862. Yet, despite the risks and expenses, the Goupil-Knoedler conduit was extremely fruitful. The New York and Paris galleries maintained a tight relationship, and the number of transactions between them increased as both businesses grew.

The Goupil & Cie - Knoedler & Co. Conduit

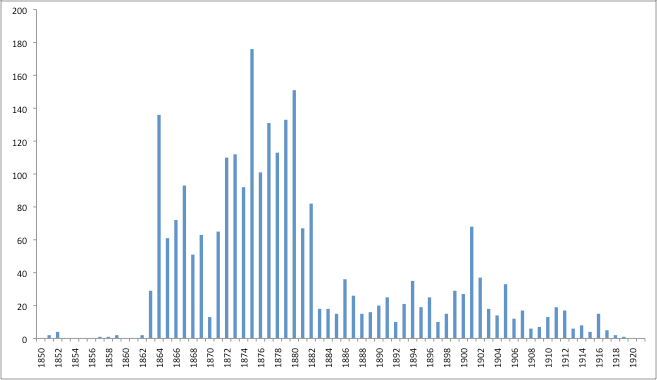

Table 1

Volume of Transactions between Goupil and Knoedler from 1850 through 1920

All in all, Goupil & Cie dominated the international art market for over 70 years (1846–1919), selling its prints and paintings of major nineteenth-century Salon artists such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, as well as those of the principal figures of the Barbizon school and the Dutch school, across Europe and the Americas. An analysis of the Goupil stock books shows that between 1857 and 1919, Knoedler, ranking first in the number of transactions, with more than 2,500 paintings bought or received on consignment, played a key role in maintaining the French dealer’s international leadership position, whose glory years, between 1865 and 1882, coincided with the apex of the Franco-American conduit.[53]

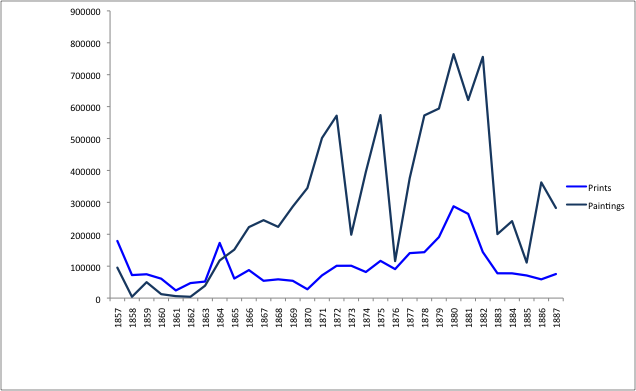

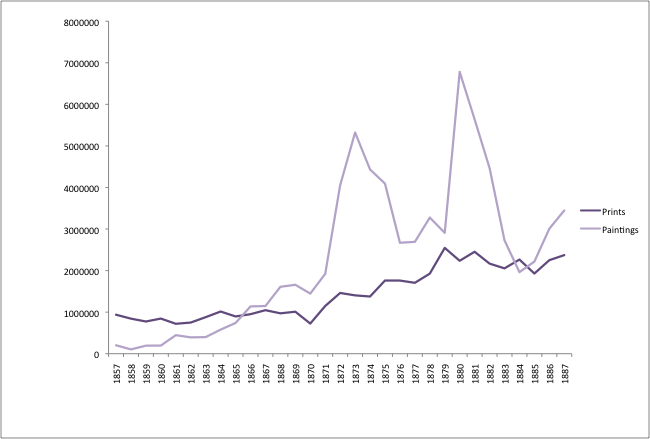

Table 2

Knoedler & Co.’s Income from 1857 through 1887 (in Francs)

Table 3

Goupil & Cie’s Income from 1857 through 1887 (in Francs)

Tables 2 and 3, showing both Knoedler & Co.’s and Goupil & Cie’s incomes between 1857 and 1887, confirm the 1865 turning point in terms of revenue. By separating the prints from the paintings, they also reveal that results of both businesses mirrored each other. Starting in 1865, for example, income generated by paintings exceeded that of prints, showing a significant shift in the international market for art.[54] Interestingly, this date marked the end of the Civil War, and American collectors’ major beginnings in art collecting. In this new era, Goupil & Cie and Knoedler & Co. were key players; the French dealer supplied his New York partner with the finest prints and paintings from Europe and had in Knoedler a prestigious ally in this growing market.

The high number of transactions between the two dealers provides a good idea of the evolution of taste for European art in the United States. During the 1860s, for example, Knoedler & Co. favored French art, and more particularly, the 1810–20 generation of Salon and genre painters, such as William Bouguereau, François-Claudius Compte Calix, Eugène Fichel, and Lanfant de Metz. The Hague school artists also held a privileged position in Knoedler’s stock, and among them, Petrus Paulus Schiedges’s marine paintings excelled.[55] While developing their close business relationship, Knoedler and Adolphe Goupil maintained a faithful friendship, which extended to Goupil’s son, Albert (1840–84). In 1872, for example, Knoedler gifted a yacht to Albert.[56] That same year marked the recovery after the Franco-Prussian war and the culmination of not only Knoedler and Goupil’s friendship but also their business interactions, with an average of 10 paintings sent to America each month. The war caused great economic upheaval and almost eradicated the art market in France, since many artists, including Jean-Léon Gérôme, and dealers such as Paul Durant-Ruel, went into exile in London.[57] Adolphe Goupil’s whereabouts during the wartime are not certain. The stock books of the firm reveal, however, that he was able to maintain some semblance of business normalcy through his American outlet, perhaps from one of his country houses in Bougival or Tourlaville in Normandy,[58] where he may have had his stock of paintings and prints shipped.

Starting in the 1870s, it was their particular attention to American sensibilities that led Goupil & Cie and Knoedler & Co. to become such powerful figures on the American art scene. Their timing was perfect: the establishment of their business partnership came shortly before the early years of the Gilded Age, an era of unprecedented economic growth that followed in the wake of the Civil War and brought with it a growing demand for European art, with collectors building art collections for both their own enjoyment and public patronage. This surge of interest in the arts and collecting, commonly referred to as the era of “tableau mania,” would prevail through the rest of the century. A New York Times article from 1884 estimates that “the purchases of French pictures by Americans rose from $701,000 in 1877 to $1,997,000 in 1882.”[59]

In response, Knoedler and Goupil ensured that they supplied the American collectors with the art they favored, which followed the common trend established in the previous years. Looking back at Goupil-Knoedler transactions, the French painter Charles Kuwasseg, with more than 85 paintings sold, took the lead, just ahead of the popular Adolphe Bouguereau and Jean-Léon Gérôme, who were themselves followed by artists from the Barbizon school, including Camille Corot, Karl Daubigny, Narcisse Díaz de la Peña and Félix Ziem. The Dutch school also continued to hold a strong position, although Frederik Kaemmerer’s genre scenes were gradually replacing Schiedges’s marines.[60] However, an analysis of the Goupil stock books shows that, despite the favorable market conditions, transactions between Goupil and Knoedler plummeted from an average of a little over 100 paintings per year during the 1870s to less than 40 per year in the 1880s. By 1883, the number of paintings sold by the French dealer to his American counterpart had reached an unprecedented low. The main reason for this decline was the American protectionist tariff law of 1883, approved during an economic and financial crisis.[61] This law, which raised the ad valorem duties on imported artworks from 10 percent to 30 percent, had a hugely negative impact on the international art market.[62]

Goupil’s legacy in America is closely linked to the conduit the French gallery established with Michael Knoedler, who further developed the market for art in the United States. As a result, both Knoedler’s and Goupil’s longevity and strategies made the dealers key protagonists in the creation of some of the most famous nineteenth-century private American collections, including those of William Tilden Blodgett, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe, William Walters, Alexander Turney Stewart, Henry Clay Frick, and through them and their bequests, public collections, too, including those belonging to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Walters Art Museum.[63] For example, when it was exhibited at the 1881 Salon, Goupil purchased The Spy (fig. 3),[64] one of the most emblematic paintings of the military painter Alphonse de Neuville, depicting the Franco-Prussian war. The Goupil stock books show Knoedler as the buyer in 1881,[65] who then sold it to Charles A. Whittier from Boston in October of that year. In 1900, Colis P. Huntington, its subsequent owner, bequeathed it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it remains today.[66]

Goupil’s, after Goupil & Cie

In 1857, Michael Knoedler bought out Goupil New York and renamed it Goupil & Co., M. Knoedler Successor. Keeping the name Goupil on the letterhead, in the local directory, on the front window—such as shown on an 1864 photograph of the 772 Broadway location (fig. 4)—and in advertisements (fig. 5) was crucial to underscoring the affiliation of his firm with the prestigious gallery. In particular, the highly decorated Broadway storefront shows a palette and brushes in the upper corner, reminiscent of Paff’s old establishment on Barclay Street, which featured a plaster cast of a cupid with palette and brushes.[67] The name on the façade is Goupil and not Knoedler, exemplifying Knoedler’s efforts to remain identified as “Goupil’s.”[68] Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, in 1863, when Knoedler officially finished paying out the business, the name Knoedler replaced New York in the Parisian stock books, as buyer identification. On its letterhead, however, Goupil & Cie did not remove the words succursale à New York, signaling the prestige of having an offshoot in America (fig. 6).

Significantly, when Adolphe Goupil retired in 1883, his successors chose to change the name of the firm to “Boussod, Valadon & Cie, successeurs de Goupil & Cie.”[69] According to Knoedler’s associate Walter Herckenrath, not keeping the name Goupil was “a great mistake . . . a great pity indeed, and an incalculable loss.”[70] While it is not clear whether Adolphe Goupil did not authorize the use of his name upon retiring, this change of denomination presaged an era of transformations. As Herckenrath wrote two years later, Boussod, Vadalon & Co. “really killed the goose that laid the golden egg.”[71] In 1886, unhappy with how their business was turning in America, the new directors, Léon Boussod and René Valadon, reacted by sending Eugène Glaenzer, one their associates, to explore the American market, visit some customers, and sell them paintings, exactly as Adolphe Goupil and Théodore Vibert had done forty years earlier when they sent William Schaus. By doing so, the French firm created tensions with Knoedler, altering a cordial 30-year business relationship between the two galleries. A year later, Boussod and Valadon reopened a branch in New York under the anglicized name “Goupil & Co., of Paris, Boussod, Valadon & Co., Successors” but immediately faced Knoedler’s opposition, as two successors of Goupil could not coexist in the American market. In 1891, those two major international art galleries engaged in a heated legal battle over the ownership of the name Goupil & Co., a “brand name” that would empower the winner with the reputation of the influential, successful, and respected gallery. The lawsuit ended in a status quo. Both galleries were allowed to use the name Goupil, with a slight twist: Knoedler, as the successor of Goupil; Boussod and Valadon, as the successor of Goupil of Paris. At the turn of the century, although Knoedler & Co. had succeeded in making a name for itself, it was still using the name Goupil in its ads (fig. 5).

These legal tensions only compounded an already declining business relationship. Furthermore, Boussod and Valadon’s strategy, which continued Goupil’s principle of flooding the market with prints made after the very same artists that once made its glory, became gradually outdated and criticized by Knoedler & Co. According to Herckenrath in 1886, “It may be they [Boussod, Valadon & Cie] went on the principle of ‘let us make hay while the sun shines’ and that they did well. Now that the clouds leave us to overcast them, it is the natural consequence of events which they themselves created.”[72] Furthermore, in 1896, with the opening of branches in Paris and London,[73] Knoedler obtained direct access to collections and artists in Europe and no longer needed the French dealer’s network. In the early 1890s, unlike Knoedler & Co., Boussod, Valadon & Cie strengthened their decades-long artistic traditions and neglected a significant shift of taste. According to the Goupil stock books, after 1900, for example, no painting by Bouguereau and only a handful of Gérômes entered America. This stubborn commitment to the same artists for such a long period became both Boussod, Valadon & Cie’s trademark and its curse, and impaired the already loosened ties with the American dealer.

Conclusion

By establishing a branch in New York in 1848, Goupil, Vibert & Cie pioneered a multinational gallery system that significantly influenced the business of art in America. Their strategy relied on three main principles: Developing the taste for the artists they represented by means of exhibitions and high media coverage, branding their name to earn their clients’ trust, and establishing a tight relationship with a local agent. Although Goupil & Cie operated as such only nine years in the United States, the large number of works in public and private American collections bearing a Goupil provenance today, as well as the myriad of prints with which the dealer flooded the country, is testimony to Goupil’s success in this country. During the Boussod, Valadon & Cie era however, the French dealers remained more modestly present in America, selling paintings that gradually fell out of favor. In 1902, they sold their New York branch to Eugène Glaenzer, the manager at the time. In 2011, when Knoedler & Co. closed its doors, it was the oldest and one of the most prestigious galleries in New York.

This article stems from my PhD dissertation and was enriched thanks to the Fellowship Program at the Center for the History of Collecting in America at The Frick Collection and Art Reference Library, New York. I wish to thank Inge Reist, Samantha Deutsch and Esmée Quodbach, as well as Julie Ludwig and Susan Chore for their help in the archives. I am grateful to editors Robert Alvin Adler, Petra Chu, and Isabel Taube for their insightful comments. I am also deeply indebted to DeCourcy E. McIntosh for his invaluable advice and fruitful conversations.

Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are by the author.

[1] Between 1829 and 1919, the activities and functions of the firm correspond to numerous corporate names: Henry Rittner (1829–31), Rittner & Goupil (1831–40), Goupil & Vibert (1841–46), Goupil, Vibert & Cie (1846–50), Goupil & Cie (1850–84), Boussod, Valadon & Cie (1884–1919), Jean Boussod, Manzi, Joyant & Cie (1900–1917). For clarity purposes, art historians tend to use the generic term “Goupil,” which will also be used in this article.

[2] Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, Canvas and Careers, Institutional Change in the French Painting World (New York: Wiley, 1965).

[3] For an analysis of the interplay between reproductive prints and art dealing, see DeCourcy E. McIntosh, “Goupil et le triomphe américain de Jean-Léon Gérôme,” in Gérôme & Goupil, art et entreprise, ed. Hélène Lafont-Couturier, exh. cat. (Paris, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2000), 31–43.

[4] These archives complement the Goupil & Cie/Boussod, Valadon & Cie stock books. Both archives are searchable on “Dealer Stock Books,” Getty Research Institute, last accessed October 25, 2016, http://piprod.getty.edu/starweb/stockbooks/servlet.starweb?path=stockbooks/stockbooks.web.

[5] “Cet établissement situé dans le meilleur quartier de New-York [sic], se compose d’une maison entière louée encore pour 8 ans; moyennant le prix de 13 000 francs par an. Un pot-de-vin de 40 000 francs fut payé en entrant.” Alfred Mainguet, Note soumise à Messieurs les arbitres par M. Mainguet relativement au mode de liquidation de la maison Goupil et Cie (Paris: J. Claye, December 1855), 19 [on microfiche], Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

[6] “Jusqu’en 1848, l’exportation des estampes pour les États-Unis avait été presque nulle, l’exportation des tableaux n’existait pas.” Adolphe Goupil, “Note soumise à MM. les membres du jury par Goupil & Cie,” in Exposition universelle de 1855 (Paris: Imprimerie De Claye, 1855), 2 [on microfiche], Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

[7] Malcolm Goldstein, Landscape with Figures: A History of Art Dealing in the United States (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

[8] Catherine Hoover Voorsanger and John K. Howat, eds., Art and the Empire City: New York, 1825–1861 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000).

[9] C. L. Beaumont was the son of John P. Beaumont, who entered the field of art dealing in the early years of the 19th century. See Florence N. Levy, “The Art Market,” American Magazine of Art 9, no. 1 (November 1917): 4–15.

[10] C. L. Beaumont, “The Picture Sales of New York, a Retrospective History,” New York Times, December 11, 1897, 18.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Mrs. Jonathan, Sturgis, Reminiscences of a Long Life (New York: F.E. Parrish, 1894).

[13] See Joy Sperling, “Art, Cheap and Good: The Art Union in England and the United States, 1840–60,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 1, no. 1 (Spring 2002), accessed October 2016. http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring02/qart-cheap-and-goodq-the-art-union-in-england-and-the-united-states-184060.

[14] “Par leur établissement de New York, dont l’importance s’accroit chaque jour, MM. Goupil et Cie ont ouvert en Amérique un débouché considérable aux estampes et à la peinture françaises et étrangères.” (With their New York branch, whose importance grows every day, MM. Goupil & Cie have opened in America a considerable outlet for French and foreign prints and paintings.) Goupil, “Note soumise à MM.,” 2.

[15] Ibid.

[16] McIntosh, “Goupil et le triomphe américain,” 31–43.

[17] “Broadway n’est pas seulement la rue la plus élégante, la plus animée, la plus aristocratique, et souvent la plus crottée de New York: c’est aussi la plus amusante, la plus riche en curiosités de tout genre.” “American Art-Union,” in Revue du nouveau-monde, ed. Régis de Trobriand (New York: Régis de Trobriand, 1850), 1:182.

[18] Mainguet, Note soumise, 19.

[19] “En 1848, le chiffre des ventes réalisées s’élevait à 119 651 francs, en 1849, 188 601 francs.” Alfred Mainguet, Résumé de la défense de M. Mainguet (Paris: J. Claye, December 1855), 45 [on microfiche], Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

[20] “Je n’ai donc point été étonné en lisant tout ce que vous dites de Schaus, je ne puis donc que vous répéter ce que je disais dans ma précédente: vous avez eu une bien heureuse idée d’aller aux États-Unis. . . . Suivant moi, il importe avant tout d’apporter l’ordre et la lumière en toutes choses. Vous êtes là, nous avons donc la tranquillité de ce côté. Vous aurez du mal, je le sais, à dompter le caractère de Schaus qui se croit un homme supérieur.” Goupil to Mainguet, November 7, 1850, ibid., 15.

[21] Goldstein, Landscape with Figures, 39.

[22] “Au premier sont les magasins de gros pour les estampes et articles de couleur, la galerie de tableaux; dans les étages supérieurs, 3e et 4e, des ateliers et les logements de gérant et des principaux employés, pour lesquels ils paient un loyer; dans les caves (sous-sols) les réserves des magasins; dans un pavillon situé au fond et séparé par une petite cour, les ateliers des broyeurs, menuisiers, charpentiers, etc.” Goupil, “Note soumise à MM.,” 19.

[23] “Cette maison contient au rez-de-chaussée un immense magasin de cent pieds de long sur vingt-cinq de large; c’est le magasin de détail pour les estampes en feuilles ou encadrées, les tableaux, les articles de couleur et de dessin, les glaces, etc.” Ibid.

[24] Ibid., 2.

[25] “Lettres et arrêté ministériel du 28 août 1850,” inv. F/21 033, file 39, Archives Nationales, Paris.

[26] “The Dieterle Family Records of French Art galleries (1846–1986),” inv. 900239, boxes 1 to 15, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[27] “Le Humboldt,” Courrier des États-Unis, December 12, 1853, 1.

[28] La Femme au miroir, a watercolor by Edmond André, and Moissonneuse et Blondine, by Houssaye de Léoménil, inv. nos. 183 and 180, purchased for 200 francs for both; Ronde de Mai, a copy by Joseph Caraud, after Charles Muller, inv. no. 95, purchased April 20, 1850, for 300 francs. “The Goupil stock books,” box 5.

[29] Inv. no. 2, purchased ca. 1848 and sold in 1851 to the New York branch for 250 francs.

[30] Bernard Roelker, US Tariffs, a Manual for the Use of Notaries Public and Bankers (New York: Bankers’ Magazine, 1857).

[31] Mainguet, “Note soumise à Messieurs les arbitres par M. Mainguet,” 9.

[32] According to inventory dated December 31, print stock was valued at over 360,000 francs and painting stock at 11,410 francs. Ibid., 8–9.

[33] Ernest Gambart to William Rossetti, July 5, 1857, in Jeremy Mass, Gambart, Prince of the Victorian Art World (London: Barrie and Jenkins, 1975), 94.

[34] Richard Peters, ed., The Public Statutes at Large of the United States of America (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1846), 3:313.

[35] The International Art-Union, Prospectus of the International Art-Union (New York: The International Art-Union, 1849), 3.

[36] “The International Art-Union,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union, no. 8 (November 1849), 13.

[37] “Distribution des prix de l’International Art-Union,” Courrier des États-Unis, January 12, 1850, 410.

[38] “Another Exhibition of French and English Paintings,” New York Times, September 10, 1859. Goupil sent several paintings, including three studies by Joseph Caraud after Primavera by Muller (inv. no. 115 to 117, “The Goupil stock books,” box 1) all bought for 600 francs on April 20, 1848. Those studies were subsequently sold for 1.239,75 francs in New York on March 17, 1859.

[39] Adolphe Goupil to Michael Knoedler, April 3, 1856, exhibit 32, Case File J-4606: John Knoedler, Roland F. Knoedler, Edmond L. Knoedler, and Charles L. Knoedler vs. Leon Boussod, Rene Valadon, Etienne Boussod and John Doe and Richard Roe, members of the co-partnership firm of Boussod, Valadon & Co., and Eugene W. Glaenzer; Equity Case Files; U.S. Circuit Court for the Southern District of New York; Records of District Courts of the United States Record Group 021; National Archives at New York City (cited hereafter as Case File J-4606).

[40] “Les affaires d’art, comme les arts sont perdus en France pour bien longtemps.” Paul Delaroche in 1848, “Plaidoirie de Me Léon Cléry, avocat de MM. Goupil et Cie,” Affaire des héritiers de Paul Delaroche contre MM. Goupil et Cie,” 5, inv. 4°D183, Archives de la ville de Paris, Paris.

[41] Rapport du Préfet de Paris au Ministre sur la légitimité de la demande de Goupil au grade d’Officier de la légion d’honneur, August 3, 1877, inv. F12 5158, Archives Nationales, Paris.

[42] Goupil, “Note soumise à MM.,” 2.

[43] “Deux des associés de la maison, M. Vibert et M. Goupil fils aîné, successivement chargés de l’organisation et de la direction de la maison d’Amérique, succombèrent, l’un en 1850, à l’âge de trente-quatre ans l’autre, en 1855, à l’âge de vingt-cinq ans, à la suite de maladies causées par des travaux opiniâtres et des voyages longs et pénibles dans un climat insalubre.” Goupil, “Note soumise à MM.,” 3–4.

[44] Goupil to Knoedler, October 4, 1855, exhibit 1, Case File J-4606.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] DeCourcy E. McIntosh, “Merchandising America: American Views Published by the Maison Goupil,” Antiques 164, no. 3 (2004): 124–33.

[48] Adolphe Goupil to Michael Knoedler, December 8 1856, exhibit 5, Case File J-4606.

[49] Sale agreement between Adolphe Goupil and Michael Knoedler, April 14 1857, exhibit 40, Case File J-4606.

[50] “Quant aux tableaux, ils seront vendus distinctement et sur les indications de prix spécialement données par MM Goupil & Cie et M. Knoedler sera garant du recouvrement de ce prix mais il aura droit au partage du bénéfice qui sera fait par lui après réduction des frais de port et de douane.” Ibid.

[51] Knoedler & Co. records, inv. 2012.M.54, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[52] Knoedler inventory, book 2, page 66, “Dealer Stock Books,” Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, accessed December 9, 2016, http://archives.getty.edu. Priced at 15,000 francs, Charles Baugniet’s Les premiers pas (Goupil inventory no. 7828) was the most valuable work included in the shipment.

[53] Goupil, “Note soumise à MM.,” 2.

[54] Tables 2 and 3. Calculation based on figures in table “Affaires Estampes et Tableaux 1857–1887,” September 25, 1890, exhibit 30, Case File J-4606.

[55] Agnès Penot, La maison Goupil, galerie d’art internationale au XIXème siècle (Paris: Mare & Martin, 2016), 307–16.

[56] Adolphe Goupil to Giuseppe De Nittis, August 20, 1872, in Enrico Piceni and Mary Pittaluga, De Nittis (Milan: Bramante, 1963), 327.

[57] “Les artistes avaient quitté Paris pour la plupart: les uns, afin de n’être point forcés de servir dans les rangs de la garde nationale, une cause ou des passions qui leur répugnaient; les autres, afin de fuir le spectacle honteux de cette seconde terreur.” Alfred Darcel, “Les musées, les arts et les artistes pendant la commune (7e et dernier article),” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 2nd per., 5 (June 1, 1872): 490.

[58] Inventaire après décès de Monsieur Adolphe Goupil, May 17, 1893, inv. ET/XII/1450, Minutier Central, Archives Nationales, Paris.

[59] “Cheap French Pictures,” New York Times, July 13, 1884.

[60] See DeCourcy E. McIntosh, “Goupil’s Album: Marketing Salon Painting in the Late Nineteenth Century,” in Twenty-First-Century Perspectives on Nineteenth-Century Art, ed. Petra ten-Doesschate Chu and Laurinda S. Dixon (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2008), 77–84.

[61] William J. Barber, “International Commerce in the Fine Arts and American Political Economy, 1789–1913,” in Economic Engagements with Art, Annual Supplement to Volume 3: History of Political Economy (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1999), 209–33.

[62] Madeleine Fidell Beaufort and Jeanne K. Welcher, “Views of Art Buying in New York in the 1870s and 1880s,” Oxford Art Journal 5, no. 1, Patronage issue (1982): 48–55.

[63] Penot, “La maison Goupil,” 359–65.

[64] Goupil inventory no. 15065, “Dealer Stock Books,” Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[65] Knoedler inventory no. 3509, “Dealer Stock Books,” Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[66] The late Provenance of The Spy was provided by the website of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed October 10, 2016, http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437219; and Robert Jay, “Alphonse de Neuville’s The Spy and the Legacy of the Franco-Prussian War,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 19/20 (1984-85): 151–62.

[67] Beaumont, “Picture Sales of New York,” 18.

[68] Knoedler v. Glaenzer, 55 F. 895 (2d Cir. 1893).

[69] Acte de la société Boussod, Valadon & Cie, 22 avril 1884 (effet rétroactif au 1er avril 1884), Minutier central, inv. ET/I/1413, Archives Nationales, Paris.

[70] Walter Herckenrath to Roland Knoedler, May 26, 1884, “Knoedler & Co. records,” inv. 2012.M.54, box 1499 (private correspondence), Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[71] Walter Herckenrath to Roland Knoedler, May 14, 1886, “Knoedler & Co. records,” inv. 2012.M.54, box 1499 (private correspondence), Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[72] Ibid.

[73] De Courcy E. McIntosh, “Expanded Timeline,” De Courcy McIntosh Research Files, unprocessed collection, The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives, New York.