The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Spectaculaire Second Empire, 1852–1870 (The Spectacular Second Empire, 1852–1870)

Musée d’Orsay - Paris

September 27, 2016–January 15, 2017

Catalogue (French language only):

Spectaculaire Second Empire.

Edited by Guy Cogeval, Yves Badetz, Paul Perrin, and Marie-Paule Vial.

Essays by Guy Cogeval, Xavier Mauduit, Anne Dion-Tenenbaum, Marie-Laure Deschamps-Bourgeon, Laure Chabanne, Gilles Grandjean, Paul Perrin, Sylvie Aubenas, Michaël Vottero, Émilie Bérard, Arnaud Denis, Audrey Gay-Mazuel, Viviane Delpech, Yves Badetz (2), François Loyer, Jean-Claude Yon, Alice Thomine-Berrada, Hervé Lacombe, Nicole R. Myers, Isabelle Cahn, Laure de Margerie, and Ana Debenedetti.

Paris: Musée d’Orsay / Paris: Éditions Skira Paris, 2016.

320 pp; appr. 250 color and b&w illustrations; timeline; bibliography; index.

Euro 45 (cloth)

ISBN-10: 2370740426

ISBN-13: 978-2370740427

The exhibition Spectaculaire Second Empire (The Spectacular Second Empire), which closed on January 15 of this year, celebrated the 30th anniversary of the Musée d’Orsay (fig. 1). It was the last exhibition organized by the museum’s current director, Guy Cogeval, who stepped down on March 15, 2017. Cogeval was assisted by three Orsay curators: Yves Badetz, Paul Perrin, and Marie-Paule Vial.

True to its title, the exhibition focused on the “spectacular” aspects of the Second Empire, the period when France was ruled by Napoléon III, the nephew of Napoléon I. Charles-Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte had come to power legitimately in 1849 as the president of the Second Republic (1849–51), staged a coup to retain his power after his presidential term ended (December 2, 1851) and, one year later, pronounced himself emperor (December 2, 1852). The Second Empire, as the Musée d’Orsay’s website for the exhibition reminds us,[1] was a period rich in contradictions. Napoléon III’s iron grip on the country, particularly during the first decade of the empire, met with strong opposition; economic development was accompanied by social unrest; the radical rebuilding of Paris ordered by the emperor of necessity meant destruction and displacement. Yet, as the purpose of the exhibition was to show “the entertainment and festivities of the Second Empire and . . . the different ‘stages’ on which our modernity was invented,”[2] these contradictions were largely invisible in the exhibition. The focus was on Napoléon III and his wife Eugénie and the glamorous high life that was a hallmark of their reign.

The theme of the exhibition was very much of our time. A fascination with royalty and high life seems to be the order of the day despite (or, perhaps, because of) the rise of populism across, at least, the Western world. The success of Netflix’s The Crown, followed by Masterpiece Theatre’s Victoria—not to speak of the earlier success of Downton Abbey—all demonstrate that the glitter of diamonds and the flicker of crystal and high-polished silver have a new mass appeal—one that the Musée d’Orsay seemed eager to tap into.

Clearly laid out, the exhibition had thirteen thematic rooms, which highlighted the personalities and public life of Napoléon III and Eugénie as well as the life of the aristocracy and upper bourgeoisie that profited from their rule. The theme of each room was briefly summarized in a short wall title, such as “Fastes dynastiques” (dynastic pageantry) or “Portraits d’une société” (portraits of a society); the rooms were set off from one another by different background colors or decorations. The room devoted to fastes dynastiques, for example, had a ceremonial curtain painted along its walls.

Entering the first or, rather, the anteroom of the exhibition (fig. 2), one’s first encounter was with Ernest Meissonier’s well-known painting, The Ruins of the Tuileries Palace (Musée National du Palais, Compiègne), a curious but thought-provoking curatorial choice that served as a reminder that the spectacular splendor that one was to see in the exhibition was short-lived—a little shy of eighteen years. The only other object in the anteroom was a huge and ostentatious Sèvres vase, commemorating the 1866 charitable visit of Empress Eugénie to Amiens at the time of the cholera epidemic. It stood in a niche that opened to the first thematic room of the exhibition, so that the object could be seen from both rooms and from two different sides.

The first exhibition room (fig. 3) was dominated by two life-size state portraits of Napoléon III and Eugénie, facing one another, both painted by that darling of the Second Empire court—François-Xavier Winterhalter.[3] Between them, in the center of the room, was a flat showcase featuring the very same diadem made of gold studded with small diamonds and colossal pearls that Eugénie is wearing in the portrait. Next to it was Eugénie’s crown, commissioned by Napoléon III in 1855 (together with his own, now lost) from Alexandre-Gabriel Lemonnier and shown off at the 1855 International Exposition in Paris. Both the diadem and the crown are today part of the collection of French crown jewels in the Louvre.

To offset the symbol-laden ceremonial portraits of the emperor and the empress, two works in the room, a painting and a sculpture, showed the rulers’ populist side. William Bouguereau’s The Emperor Visiting the Victims of the Tarascon Flood (Hôtel de Ville, Tarascon) and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s plaster model for a never-executed sculpture of Empress Eugénie Protecting the Orphans and the Arts (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Valenciennes), respectively, have the emperor and the empress momentarily mingling with the plebs. The couple was shown in a more official function on the opposite wall of the room in the well-known painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme showing the Reception of Siamese Ambassadors by Emperor Napoléon III at the Palace of Fontainebleau, 26 June 1861 (Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon). This painting, in addition to showing the glamour of the interior of Fontainebleau, also served to emphasize the reach of the Second Empire, as it suggests that Napoléon III ruled not only over France but also over its colonies, the total area of which he doubled in the course of his reign.

The second room (fig. 4) was devoted to fastes dynastiques. Its centerpiece was the elaborate cradle made for the prince impérial, born in 1856 (Musée Carnavalet, Paris). Designed by Victor Baltard, Architect of the City of Paris (famous for his design of Les Halles), it was executed by an army of artists and artisans, from painters and sculptors to metal casters and lace makers. The painter Hippolyte Flandrin made the designs for the enamel plaques on the sides of the cradle, while Pierre-Charles Simart modeled the allegorical figure of Paris holding the crown in addition to smaller figures of sirens and winged spirits. An entire wall opposite the cradle contained a detailed timeline of the Second Empire. The room also included a watercolor by Eugène Lami of the civil wedding ceremony of Napoléon III and Eugénie in the Tuileries Palace and another one by Hébert Clerget representing their sacramental marriage in Notre Dame Cathedral (both in the Musée National du Château de Compiègne). The latter served to remind the viewer that, like his uncle, Napoléon III chose Notre Dame in Paris as the imperial church to clearly distinguish his rule from that of the French kings, who favored the Cathedral of Reims. Numerous photographs of the imperial marriage and the baptism of the prince impérial rounded out the theme of the room and allowed for some interesting comparisons. It is notable that the baby prince impérial is photographed not in his official cradle but in one that is simpler and in all likelihood more practical. Some of the photographs were made by Ambroise Richebourg, official photographer of the Second Empire, others by Charles Marville and Gustave Le Gray.

The focus on pageantry of the second room continued in the third, which was devoted to celebrations not directly linked to the imperial family but intimately connected to imperial rule. As Xavier Mauduit remarks in the exhibition catalogue (p. 41), “Napoléon III chooses to expose imperial dignity through pageantry. . . . He adapts the comedy of power to the circumstances and to the expectations of the population.” (Napoléon III fait . . . le choix d’exposer la dignité impériale dans le faste. . . . Il adapte la comédie du pouvoir au contexte et aux attentes de la population.) Everything from the obscure martyr St. Napoléon’s feast day (established by a decree of Napoléon I in 1806) to the triumphant return of armies after winning a war, deserved a celebration. Specialized firms, including the Maison Belloir et Vazelle, were in charge of the design of ephemeral street decorations, such as triumphal arches, daises, and tents (fig. 5). The room featured several of these designs acquired by the Musée d’Orsay in 2015 from the dealers Jacques Sargos and Jane Roberts.[4] It showed a series of watercolors by Léon Leymonnerye documenting a variety of festivities, including the inauguration of some of the new streets and boulevards built as part of Napoléon III’s overhaul of Paris orchestrated by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. Leymonnerye’s watercolors were complemented by a slide presentation of a series of photographs by Marville showing the “nouveau Paris.” They served as a pointed reminder that Marville documented not only what was torn down—the photographs that we see most often—but also what was newly constructed.

“Résidences imperiales” (imperial residences) was the theme of the fourth room, which contained numerous large photographs by Edouard Denis Baldus and Richebourg centered on the Louvre and the Tuileries Palace, Napoléon III’s principal winter residence,[5] destroyed during the Commune in 1871. Several of them focused on the new wing of the Louvre, opposite the Grande Galerie and parallel to the rue de Rivoli, and were accompanied by architectural plans showing phases of the construction. A large painting by Emmanuel Lansyer and another by Charles Giraud (La Salle des Preuses) presented the exterior and one of the interiors of the Castle of Pierrefonds, the medieval ruin bought by Napoléon I and rebuilt as an imperial residence by Napoléon III (fig. 6).[6] The room also contained watercolors and photographs of other imperial residences, specifically the palaces at St. Cloud and Fontainebleau. Of special interest were some of the photographs of the interior of the Chinese pavilion at Fontainebleau, which featured the objects Empress Eugénie received as gifts from various participants in the looting and destruction of the Chinese imperial palace Yuanming Yuan at the end of the Second Opium War (1856–60).

While the first four rooms were relatively small, the fifth was a large hall, entitled “Portraits d’une société” (fig. 7). It was entirely devoted to portraiture executed in various media of the aristocracy and the middle class of the period. The walls were hung with rows of portraits—interrupted by marble busts as well as a number of large Sèvres vases—which gave a hint of the opulent interiors in which many of these portraits must originally have hung. Both the painted and the sculpted portraits presented an array of men and women ranging from establishment figures like Prince Napoléon, the son of the youngest brother of Napoléon I (Hippolyte Flandrin) and Madame Moitessier, wife of a wealthy banker (Jean-Auguste Ingres) to the socialist philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon with his family (Gustave Courbet) and the dwarfed and hunchbacked painter Achille Emperaire[7] (Paul Cézanne), enthroned on a chair as if he were empereur instead of Emperaire.[8]

The choice of Courbet’s portrait of Proudhon (Petit Palais, Paris) was particularly intriguing. The author of the famous phrase, “Property is theft!” (La propriété, c’est le vol!) seemed out of place, in his peasant blouse, among the powerful, rich, and famous of his day. Was it intended as a veiled acknowledgment that there was another side to the Second Empire? That the Empire was not without its critics? Or that, precisely through their criticism, men like Proudhon could achieve “spectacularity?” Neither the labels nor the catalogue presented an answer to that question.

While most of the portraits in the room were of single individuals, men or women, there were a number of family portraits, including Courbet’s of the Proudhon family and Edgar Degas’s of the Bellelli family (Musée d’Orsay, Paris), in addition to the striking group portrait by James Tissot of the members of the exclusive club called Le Cercle de la Rue Royale (fig. 8). Founded in 1852, this club counted among its members scions of the oldest aristocratic families in France, such as the Prince de Polignac, as well as some of the wealthiest among the Second Empire nouveau-riche including the banker Charles Haas, who became one of the models for Marcel Proust’s Swann in À la recherche du temps perdu. The twelve members represented in Tissot’s painting paid the artist one thousand francs each for the inclusion of their portrait, which hung in the club on the rue Royale. Ownership of the painting upon closure of the club was assigned, by drawing lots, to one of the members or his heirs. The work was acquired under Cogeval’s directorship for some four million euros.

Portrait photographs were featured in two large vitrines placed along the central axis of the room separated by two huge candelabras by Charles Crozatier and Carpeaux’s well-known sculpture of the young prince impérial with his dog Néro (Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Some were large formats, like two albumen prints by Adolphe Dallemagne showing Antoine Barye and Camille Corot standing in elaborate niches à la Gerrit Dou. Others were small cartes-de-visite by André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, who patented the format in 1854. In between these two, there was a wide variety of photo formats, showing individual as well as group portraits. Perhaps the most unusual objects in the entire room, placed on top of the vitrines, were two “photosculptures” representing the dramatist Eugène Labiche and an unknown woman in a crinoline. These works were manufactured using a process invented by François Willème that anticipated today’s 3-D printing. Central to the process was the production of a large number of photographs from many different angles, the contours of which were transferred to the clay with the help of a pantograph.[9]

The next three rooms, the sixth, seventh, and eighth, were devoted to three major Second Empire styles, neo-Greek, neo-gothic, and historic eclecticism, respectively. The neo-Greek room (fig. 9) was centered on Jules Salmson’s life-size bronze sculpture, La Dévideuse (The Thread Winder). Among paintings, it featured Gérôme’s well-known rendering of the interior of the Pompeian villa of Prince Napoléon on 18 Avenue Montaigne, where he entertained his mistress, the actress Mademoiselle Rachel (Elizabeth-Rachel Félix). Her portrait by Amaury-Duval was also shown in the room, which furthermore contained a number of sculptures and decorative art objects. Among them were Eugène Guillaume’s Napoléon I, Legislator, which originally stood in the Pompeian villa, and two bronze neo-Greek lamps by Ferdinand Barbedienne.

Neo-gothic was closely linked, in the exhibition, to the Catholic revival of the middle of the century, exemplified by Jules Breton’s The Benediction of the Wheat Harvest in the Artois (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Arras). On either side of the painting were two neo-gothic tours-de-force of orfèvrerie, a monstrance and a reliquary (fig. 10), designed by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc and manufactured by the well-known goldsmith Placide Poussielgue-Russand. Commissioned by the emperor for Notre Dame, both were shown at the International Exhibition of 1867 before reaching their final destination in the imperial cathedral. The room also featured the surround of a procession dais, woven in Beauvais, which formed a nice connection with Breton’s painting.

The eighth room, devoted to the eclectic interior, was much larger than the neo-Greek and neo-gothic rooms, suggesting that historic eclecticism was the reigning mode of interior decoration in the mid-nineteenth century. Beside a large number of pieces of furniture and home furnishings (fig. 11), the room contained paintings and watercolors by Pierre-François-Eugène Giraud, Eugène Lami, and Arthur-Henri Roberts, representing a number of specific interiors, including the office of the Comte de Nieuwerkerke in the Louvre, and a group of rooms in Baron James de Rothschild’s Chateau de Ferrières built by James Paxton between 1855 and 1859.

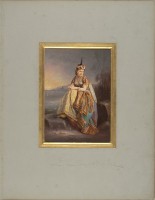

Parties and balls were the subject of the ninth room, called “Les lumières de la fête.” The theme was best represented in a series of watercolors of feasts, by such artists as Eugène Lami, Emile Reiber, and the Dutch artist Paul Tetar van Elven, which clearly demonstrated the glamour and brightness of nineteenth-century feasts made possible by wide deployment of gaslight since the middle of the nineteenth-century. As one entered the room, however, the eye was most immediately drawn to a group of nine large-scale caricatures by P. F. E Giraud, depicting some of the great party-animals of the period. The Comte de Nieuwerkerke, every week after the Friday fast, received the social elite at his home. These receptions were known for their “after” parties, during which Giraud made these and other caricatures of the guests of the count, who included artists, critics, writers, and members of the imperial family. In addition to these male images, the room also contained a number of fascinating female images—hand-colored photographs of women in the costumes they wore to masked balls. There was Empress Eugénie alternately as odalisque (fig. 12) and as dogaressa in photographs by Pierre-Louis Pierson, colored in by an artist who signed as “Marck,” and Countess Castiglione as Dame de Coeurs (photograph by Pierson and coloring by Aquilin Schad). Photographs of women and men thus staged in historic or phantasy costume were so popular that entire albums were made of them.

The room also had a large case of jewelry, most of it made by France’s famous jewelry shop, the Maison Mellerio. Founded in 1613 under the aegis of Maria de Medici, it had for two and a half centuries been the go-to shop of the royalty of Europe when they “needed” diadems, bracelets, or necklaces. The house’s fame was at its peak in 1867, when it presented a large exhibit at the International Exposition of that year. One of the most fascinating items in the room was Mellerio’s client register for 1867–68, which gives immediate evidence that from the Emperor of France to the Czar of Russia all royalty bought their jewelry from this house.

Closely related to the theme of the ninth room was that of the tenth (fig. 13), which was devoted to the theatre. Part of the room showed photographs of the old and new theaters of the day. The Opéra, today called the Palais Garnier after its architect Charles Garnier, was, of course, the pièce de résistance here, but there were also photographs of the Théâtre de Vaudeville and of the theaters on the Boulevard du Temple before they were destroyed to make place for the boulevard Prince Eugène in 1862. The important role of actresses in the nineteenth century was highlighted by a series of their portraits, including the painted portraits of Lola de Valence (Edouard Manet) and Adèle Patti (Winterhalter) and the sculpted busts of Eugénie Fiocre (Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux) and Marguerite Bellanger (Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse). The theatrical theme of the room was rounded out by a series of photographs and caricatures of actors, in addition to a small group of early theatrical posters by Eugène Chéret.

Perhaps the most unusual object in the room was a fan made of ostrich feathers set around a Jewish star, made of gold, pearls, and colored glass (which replaced the original precious stones that were removed at some point), and inscribed with the words, “Les dames Israelites à l’Impératrice Eugénie, 1860.” The fan was a present from a delegation of Jewish-Algerian women during a trip of the Imperial couple to Algeria in 1860.[10]

The eleventh room linked new leisure activities (nouveaux loisirs) with new painting (nouvelle peinture). Unlike the other rooms, it was exclusively devoted to paintings. Canvases by early Impressionists—Manet, Edgar Degas, and Claude Monet, as well as the German painter Adolph Menzel (who traveled to Paris in the mid-1850s), showed middle-class men, woman, and children in Paris parks, on the beach in Normandy or Biarritz, or at the races.

The next room, the twelfth, a very large room dedicated to the theme of the Salon (fig. 14), showed a sampling of the kind of paintings visitors might have seen at the Salons during the Second Empire. The paintings were crowded together and hung on red walls, to simulate the look of nineteenth-century Salons. One short wall held Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe, a work that, of course, was never shown at the official Salon but at the famous Salon des Refusés, the salon of the refused artists, organized by order of Napoléon III in 1863. This room was by far the least successful of the entire exhibition. It paid lip service to an entire body of artwork not elsewhere represented in the exhibition—and for good reason, as the show’s focus a priori excluded such artistic subjects as landscape and peasant painting. One got the impression, therefore, that this room was intended, in part, to make up for that lack, but all it did was to show a strange catch-as-catch-can of mid-nineteenth-century paintings whose specific rationale for being there was difficult to understand. The room contributed little to an understanding of the complex history of mid-nineteenth-century French art or, for that matter, of the history of the Salon during the Second Empire; the gratuitous presence of Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe did little to clarify the significance of this room.

The final room of the exhibit, again a very large one, was devoted to the international expositions during Napoléon III’s reign (fig. 15). Thematically, their inclusion made more sense than the inclusion of the Salons. The Second Empire, of course, witnessed the first two major international expositions held in France, the exhibitions of 1855 and 1867, which were essentially Napoléon III’s shows. He personally played a key role in both, keenly aware as he was of the potential of the exhibitions not only to highlight French industry and culture, but also to legitimize his own rule. As we have seen earlier, the emperor commissioned two spectacular crowns for himself and Eugénie, to be shown at the Exhibition of 1855, and two equally extravagant ritual objects for Notre Dame, to be shown at the Exhibition of 1867.

For the modern viewer, the room highlights the importance, little-known today, of major manufacturers—firms like Barbedienne, Christofle, Jules Desfossé, Charles-Guillaume Diehl, Fourdinois, etc.—and the skill of the craftsmen they hired, often from all corners of Europe. Visitors old enough to have seen the Second Empire exhibition shown in Paris, Detroit, and Philadelphia in 1978–79, may have been pleased to see once again the spectacular block-printed wall paper called “The Garden of Armida,” designed by “Rosenmuller” (Edouard Muller) and manufactured by Jules Desfossé, which was on the cover of the English edition of the catalogue.[11]

Just as the exhibition began with a small antechamber, it ended with a modest “post chamber,” which only featured a single work, the portrait by James Tissot of Eugénie and the prince impérial in England, commissioned by the former empress to celebrate the coming of age of her son in March 1874 (fig. 16). Dressed in a dowdy black mourning dress and a modest little pillbox hat, a portly middle-aged Eugénie and her lanky teenage son stand forlorn in a British park, fall leaves fluttering around them. The odd circumstance that they are standing on a rug, spread on the ground, in front of a table and two chairs, while they are gaped at by some promenaders in the park—a reference, as Alison McQueen suggests, to Eugénie’s Bonapartist supporters in England—appears to emphasize their loss of country and home. Sic transit. . . certainly could be the motto of this work as well as the one by Meissonier with which the exhibition opened.[12]

All in all, the Spectacular Second Empire delivered what it promised. It offered a fascinating picture of the glamourous lives of the elite of the period and brought new awareness of the emphasis on spectacle that was actively encouraged by the emperor himself. To illustrate their chosen theme, the organizers of the exhibition embraced the opportunity to show a large number of works that are rarely seen. How wonderful to see Mellerio’s jewelry and understand the environment within which it was made and worn. What a pleasure to see the scintillating watercolors of Eugène Lami, and lesser known artists like Léon Leymonnerye, whose delicate works rarely leave the cardboard boxes in which they are kept. And what a treat to see the incredible hand-colored photographs of the empress as Odalisque or Dogaressa, surprising images in every way. The use of photographs in the show, generally, was exemplary, as the viewer really gained much understanding of the reasons for and contexts within which photographs at the time were made. The same was true for the decorative arts, which shone in the exhibition and, again, gained much from a contextual presentation.

In sum, the Spectacular Second Empire was an exciting exhibition that did full justice to its chosen theme. It highlighted an aspect of Second-Empire art and culture that in the past half century has been neglected as, under the influence of the neo-Marxism of the 1960s and 1970s, scholarship tended to focus on the art of the period that engaged with the social injustices of the mid-nineteenth century. Indeed, while since the late 1960s, the literature on such artists as Courbet and Jean-François Millet has flourished, it is only in recent years that an interest in court-sponsored artists like Carpeaux and Winterhalther has been revived. Many others, whose art focused on the haut monde of the period, such as Lami and Henri Baron, are still waiting to be revalued. The focus on the culture of the powerful, the rich, and the famous, has also led to a renewed interest in the decorative arts, which were highlighted in this exhibition and formed, perhaps, its major attraction. Not only were they a feast for the eye, but in a perverted way they illuminated, at least for this viewer, the social injustice of the age.

The catalogue of the exhibition is magnificent. Beautifully designed, with excellent color plates and differently colored pages to separate individual sections, it does justice to the exhibition, visually. As for its content, the catalogue comprises twenty-three short essays, by different authors, that are only loosely related to the exhibition. The objects themselves are merely represented by a checklist at the end, which contains only the most summary information. Since so many works in the exhibition are rarely seen, and may not come out of storage again for a long time, it seems a pity that so little research on them made its way into the catalogue. But what is true for the exhibition is true, mutatis mutandis, for the catalogue as well: the mere images, of works so rarely seen, make it a valuable work.

Petra ten-Doesschate Chu

Seton Hall University

Petra.Chu[at]shu.edu

[1] “The Spectacular Second Empire, 1852–1870,” Musée D’Orsay, http://www.musee-orsay.fr.

[2] Ibid.

[3] The two portraits are owned by the Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon.

[4] On the discovery of these drawings, see “De nombreuses aquarelles du fonds Belloir & Vazelle acquises par des musées,” October 15, 2015, La Tribune de l’Art, accessed January 27, 2017, http://www.latribunedelart.com/de-nombreuses-aquarelles-du-fonds-belloir-vazelle-acquises-par-des-musees [login required].

[5] Napoléon III had a residence for each season: The Tuileries Palace for the winter, the palace at St. Cloud for the spring, Fontainebleau for the summer, and Compiègne in the fall.

[6] The two paintings were borrowed from the Musée Départemental de l’Oise in Beauvais and the Musée National du Palais in Compiègne.

[7] On the basis of Cézanne’s painting, Emperaire has been diagnosed with spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenita in an article by Manoj Ramachandran and Jeffrey K. Aronson in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 100, no. 8 (August 2007): 384–85.

[8] The four portraits are owned, respectively, by the Musée d’Orsay, Paris; National Gallery, London; Petit Palais, Paris; and Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

[9] For a more detailed explanation, see Robert A. Sobieszek, “Sculpture as the Sum of Its Profiles: François Willème and Photosculpture in France, 1859–1868,” Art Bulletin 62, no. 4 (December 1980): 617–30.

[10] The fan is discussed at length in Alison McQueen, Empress Eugénie and the Arts: Politics and Visual Culture in the Nineteenth Century (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011), 131–32, a book that sheds light on many objects in this exhibition.

[11] The wallpaper is owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

[12] McQueen, Empress Eugénie, 269–70.