The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Klimt Year in Vienna: Part Two

On Gustav Klimt’s actual 150th birthday—July 14, 2012—Googlers around the world launched their searches under a Doodle of The Kiss (1907–08; Belvedere, Vienna). Although the picture was stretched out of its square format to accommodate the logo letters in golden tesserae, the Austrian tourist board welcomed this gift. In Vienna, eight of the eleven Klimt exhibitions mounted in 2012 were still on view.[1] On the rainy eve of his sesquicentennial, a new Gustav Klimt Center opened in Kammer am Attersee, in the region where the artist vacationed each summer between 1900 and 1916 with his Lebensmensch, the fashion designer Emilie Flöge (fig. 1). The Leopold Museum returned Klimt’s On the Attersee (1900) for a week to the banks of the lake where it was painted. On the birthday in Vienna, the Wien Museum offered a colossal cake, as well as free entry to anyone named Gustav or Emilie. The Kunsthistorisches Museum scheduled free access to its temporary Klimt bridge, built to permit a breathtakingly close inspection of his stairwell paintings. The Austrian Theater Museum gave every tenth visitor that day a fridge magnet of its one Klimt painting, Nuda Veritas, along with free admission to their exhibition. The Leopold Museum and the MAK (Austrian Museum for Applied Art / Contemporary Art) organized gratis tours of their shows, and the Belvedere staged a day-long party, admitting early-bird fans between 6 and 9 a.m. to their recently opened Jubilee exhibition. At the Künstlerhaus, the artists’ society from which Klimt and eighteen colleagues resigned in 1897 to form the Vienna Secession, a morning tour concluded with a free glass of Sekt.

Even the University of Vienna, whose professors around 1900 had vigorously spurned Klimt’s three ceiling paintings for their Great Hall, joined the birthday festivities. The first faculty painting, Philosophy, belonged to the Jewish industrialist August Lederer and his wife Serena after around 1905. In that year the generous collector had provided 30,000 Kronen enabling Klimt to repay his advance and get his pictures back from the State. In October 1918, when Klimt’s colleague Kolo Moser died, he and his wife, Editha, owned Medicine, the second faculty painting, and Jurisprudence, the third. Lederer and other patrons contributed funds permitting the Österreichische Staatsgalerie (now the Belvedere) to acquire Medicine from Editha Moser, and Lederer was able to buy Jurisprudence. After the Anschluss, the new Nazi government confiscated from Serena Lederer both Philosophy and Jurisprudence, along with their sketches, ten other Klimt oils, some 200 Klimt drawings, and the rest of their collection.[2] In 1943, the museum sent Medicine with the Lederer Klimt works – “for safekeeping” – to Schloss Immendorf in Lower Austria. Fortunately, the Beethoven Frieze, also owned by the Lederers, was stored elsewhere: the three faculty paintings and all the other works in the castle burned in May 1945 in a fire set by retreating SS troops as the Russians approached. In Vienna, the ceiling spaces at the university remained empty until the installation of black-and-white photographic replicas in 2005, the centennial of Klimt’s withdrawal from the university project.[3] For the 150th birthday festivities, the university organized a tour of the Great Hall to gaze up at the central panel by Franz Matsch surrounded by bleak replicas of all four faculty pictures.[4]

As the Klimt Year passed its midpoint, synergies anticipated by the organizers and curators of the diverse exhibitions became palpable in the city. Questions that might not have been asked earlier arose at coffeehouse tables, panel discussions, lectures, and children’s workshops, as well as in social networks and blogs. An astonishing number of people wanted to discuss how many illegitimate children the bachelor artist fathered, to speculate on the precise nature of the relationship between Klimt and Emilie Flöge, or to comment on the Belvedere’s re-installation of The Kissin the central panel of a lipstick-red triptych frame (fig. 2). Many art lovers learned for the first time that Klimt’s father had been a gold engraver; in several shows they could trace that genetic strand in the work of his sons Gustav and Georg. An alert child at the Leopold Museum was concerned about whether Klimt took his cats when he moved from his Josefstadt studio to his new studio in Hietzing in 1911. Some visitors probed tour guides for more information about the photographic revenants of the faculty paintings haunting the Klimt Year shows; the museum labels read simply, “Destroyed at Schloss Immendorf, 1945,” without mentioning the expropriation in 1939 or the Lederer family.[5]

For the eleven exhibitions in Vienna, curators, catalogue essayists, designers, lighting technicians, and interpretive staff toiled for months to uproot clichés and present a fresh look at Klimt. Yet even as they delved, the tourism and souvenir industries span. A Klimt Barbie must have been a desideratum for diverting sections of two shows – at MAK and the Wien Museum – and museum shops glittered with neo-Byzantine bling. Relying on their own Klimt holdings, the Viennese museums had to seek a comfort zone between embracing kitsch and recalling the unavoidable truth of what happened to many Klimt collectors. The results in the year’s final six exhibitions are discussed below in the order of their opening dates.

Close-Up Gustav Klimt

Gerwald Rockenschaub: Plattform

Secession, Vienna

March 23, 2012– January 13, 2013 (extended from November 4, 2012)

No catalogue

The Secession in Vienna is an active art society and a powerful place of memory. The exhibition hall by Joseph Maria Olbrich , erected within six months in 1898, survives in altered form. For the new artists’ association, which had broken with the Künstlerhaus the previous year and elected Klimt as its president, the critic Ludwig Hevesi devised a motto, mounted in gold letters under the laurel-leaf dome: “To every age its art. To art its freedom.” The words continue to motivate experiment; in a gesture celebrating the hundredth anniversary of the building in 1998, the Swiss artist Marcus Geiger painted it red .

The fourteenth exhibition of the Vienna Secession – the Beethoven exhibition, which ran from mid-April to mid-June 1902 – had been equally bold. Its designer, Josef Hoffmann, specified the viewer’s path through the show. The building, conceived by its architect as a temple inspired by Segesta in Sicily, was transformed for the tribute to Beethoven into a pilgrimage site, as suggested by the worshipful figure in the poster by Alfred Roller. Appropriate to the quasi-sacral nature of the show, the exhibition-goer was obliged almost to circumambulate the cult object: Max Klinger’s polychrome marble monument to Ludwig van Beethoven (1902; Museum of Fine Arts, Leipzig). Roller took his poster design from his own painting in the central room—Sinking Night—meant to serve as a subdued backdrop to Klinger’s Beethoven in the inner sanctum of the temple.[6]

To raise art consciousness in Austria, the Secession statutes, published in the first issue of its journal Ver Sacrum(Sacred Spring) in 1898, declared that the association would strive for “a lively contact with outstanding foreign artists.” Although Secessionist Josef Engelhart had recruited energetically abroad, the Saxon Klinger was the only German sculptor among the corresponding members in 1898.[7] Engelhart had enlisted six French sculptors, however – twice the number of Austrian sculptors who were regular members – as well as Ville Vallgren, a Finn working in Paris. The most prominent name on the list was Auguste Rodin, who exhibited in the first Secession show in 1898.[8] From the fourth exhibition in 1899, the Secession purchased a plaster of Rodin’s bust of Henri Rochefort as a gift for the future modern gallery (now the Belvedere).[9] In early 1901 fourteen Rodin sculptures and eight drawings appeared in the ninth Secession show. But the renowned French sculptor had not yet seen the building.

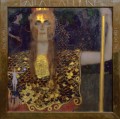

Late in May 1902, he attended a major exhibition of his work organized by the Mánes artists’ society in Prague . The show took place in their new pavilion by Jan Kotera ; the Czech architect, like Olbrich, had been a protégé of Otto Wagner. Received in Prague with the ceremony due a head of state, Rodin then traveled to Vienna, drawn by the exhibition focused on the long-anticipated Beethoven monument; Klinger was sometimes called the German Rodin. Climbing the steps of the Secession, Rodin walked past the metal doors executed by Georg Klimt, beneath the gorgons by Othmar Schimkowitz representing Painting, Architecture, and Sculpture linked by snakes (fig. 3). Brief accounts of Rodin’s three-hour tour of the show do not mention whether he was taken on the prescribed route. If so, Rodin would have turned from the foyer into the left lateral gallery. There Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze stretched some eighty-five feet along three walls of the room.

A frequently quoted conversation between Rodin and Klimt was published much later by Berta Zuckerkandl-Szeps after she fled Austria in 1938. The Viennese journalist and art critic, from the beginning an enthusiastic supporter of the Secession, had met Rodin in Paris through her French contacts.[10] The art critic Hevesi was probably a more reliable source: he published his observations on Rodin’s visit immediately after meeting him.[11] Both writers described a Wiener Jause (coffee klatsch) arranged for Rodin by Zuckerkandl in Sacher Garden in the Prater . Since the discovery and publication of a cache of postcards from Klimt in the estate of Emilie Flöge – some 400 postcards were on view in the Leopold Museum exhibition Klimt: Up Close and Personal – the gathering on the café terrace in the Prater can be dated to June 6, 1902. Klimt was invited for 5 p.m., he told Emilie, promising to try to drop by her apartment afterwards if the party did not last too long.[12]

Zuckerkandl claimed that “Klimt and Rodin had seated themselves beside two remarkably beautiful young women.” Hevesi, by contrast, noted that Rodin sat between Berta Zuckerkandl and Wilhelm von Hartel; the influential liberal minister of education, a strong advocate of establishing a gallery of modern art, was responsible for the university ceiling commission.[13] Also seated at the table, Hevesi reported, were some “famous professors on the medical faculty who did not feel insulted by Klimt’s Medicine,” the second of the university ceiling paintings. One such professor was Berta’s anatomist husband Emil Zuckerkandl, who had organized a counter protest in 1900 opposing his colleagues’ letter of complaint about Philosophy.[14] Hevesi wrote that during his visit Rodin had tirelessly explored Vienna; he disliked the wineshops of Grinzing, but adored Schönbrunn palace and the hill north of Vienna, Kahlenberg, with its view of the Danube valley. The sculptor enthused over a performance of Beethoven’s Eroica conducted by Hermann Graedener, but admitted that he had never heard Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the theme of Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze.[15]

The Austrian public, of course, knew the music. Some may even have heard Gustav Mahler’s much-criticized revision of the Ninth first performed in Vienna in February 1900.[16] As Alessandra Comini pointed out, viewers of the frieze in 1902 could recognize the opera director in Klimt’s figure of the knight in golden armor.[17] Yet few recent visitors to the Beethoven Frieze, installed in the Secession since 1986, could grasp the analogy to Mahler without a powerful lens and guidance from Comini. Built into the wall at a height of ten to fifteen feet overhead, the frieze can scarcely be examined from the floor. With the Klimt Year intervention Plattform, however, by the Austrian artist-composer-DJ Gerwald Rockenschaub, the frieze and its details could be studied up close (fig. 4).

Klimt, expecting his exhibition frieze to be dismantled, transformed his symbolic image on the long left wall in an equestrian oil version dated 1903: a knight in gold-leaf armor, the “well-armed strong man” and protector of “suffering humanity .”[18] Entitled The Golden Knight (Life is a Battle), the oil paintingcame to Vienna for the Klimt show at the Leopold Museum (fig. 5). An energetic exhibition-goer could compare the two helmets, and even visit a possible source in the magnificent armor collection at the Kunsthistorisches Museum . The helmet at the knight’s feet in the frieze reappears on his head in the painting, its visor lowered to mask the visage of the rigid profile figure in the later work. Standing in the saddle, he advances along a road paved with golden bricks toward a small snake, menacing enough to belie the pleasant meadow and allée of foliage in the background.[19]

Surely no one who mounts Rockenschaub’s lemon-colored platform at the Secession will ever call the Beethoven Frieze a fresco (fig. 6). The 1902 exhibition catalogue gave an abbreviated material description: ornamented plaster panels, with “casein paint, applied plasterwork, gilding.”[20] Marian Bisanz-Prakken, the expert on Klimt drawings at the Albertina, stresses the linear qualities of the frieze, its profiles and frontality, and its floating genii reminiscent of the Dutch artist Jan Toorop. She describes the contours of the figures as largely drawn with a brush, as well as with charcoal, graphite, or pastel crayons.[21] Klimt, she said, contrasted casein paint with gold, applying upholstery tacks, curtain rings, mirror fragments, and mother-of-pearl, as in the monster Typhon’s eyes (figs. 7 and 8). The winged ape with his scaly, coiled body dominates the “hostile forces” of the short wall, which ends with a female figure called “gnawing grief.” On the long right wall the genii reemerge and float toward “Poetry,” who will satisfy their longing for happiness (fig. 9).[22] For the linear “Poetry” in the Beethoven Frieze, Klimt made nude figure studies—as he had for the three gorgons near Typhon and for most other figures—then abandoned them to reveal his sources in reproductive prints of Greek vase paintings (fig. 10).

Although “Poetry” already showed several vertical cracks by1904, the evaluation conducted in 2009–11 reported that “the surface of the Beethoven Frieze has on the whole been preserved in relatively good condition.”[23] This is surprising, given its transport from one inadequate storage depot to another following its removal from the wall once the Klimt retrospective at the Secession had closed in December 1903. The collector Carl Reininghaus purchased the frieze, but found no suitable place to display it; neither could August Lederer, who bought it in 1915. After World War II the expropriated frieze was restituted to its rightful owner, Erich Lederer, son of the collectors, by then a resident of Geneva; he was nevertheless denied an export permit. After 1961 the frieze was stored in the Lower Belvedere until Lederer sold it to the Republic of Austria in 1973. The Federal Office for the Protection of Monuments began a restoration under the direction of Manfred Koller, completed in 1984. A 1:1 copy made during the restoration appeared in the 41st Venice Biennale that year, and in 1985 the original went on display at the Künstlerhaus in a reconstruction of Hoffmann’s lateral Secession gallery by Atelier Hans Hollein, a highlight of the exhibition Traum und Wirklichkeit. After the show closed in October 1985, the Beethoven Frieze returned at last to the Secession. On loan from the Belvedere, it was installed in a new basement gallery designed by Adolf Krischanitz, again preserving the proportions of the Hoffmann space.

In the foyer to that basement gallery during Klimt Year, a useful twin exhibition served as a prelude to Rockenschaub’s Plattform. A joint project by the Federal Office for the Protection of Monuments and the Institute of Conservation and Restoration at the Academy of Fine Arts, directed by Wolfgang Baatz, the show included photographs on the conservation history of the frieze and a film on the recent assessment of its condition. A second film documented the construction of a new full-scale replica of “Poetry,” chosen as the frieze segment in which Klimt deployed the greatest variety of materials (fig. 11). Visitors could watch a recent graduate of the conservation institute sawing planks for the wooden support, laying down reed mats to back the plaster, using a cartoon to pounce outlines of the figure onto the dried surface, applying color and curtain rings, mirrors and gold leaf. To see the film demonstrating the artist’s technique, then to approach the original at eye level, made the Secession contribution to Klimt Year one of its most rewarding experiences.

At the press conference before the opening, a journalist asked Rockenschaub what relationship he had with Klimt’s work prior to the project. “Not any,” he said, a terse reply worthy of the reticent Klimt himself. In fact, Rockenschaub, known as a Neo-Geo artist, had shown a site-specific, untitled piece in the Beethoven Frieze gallery in 1988 in an exhibition entitled IN SITU. In front of the central Typhon wall, he placed a small gold-framed picture on a red satin cushion atop a Plexiglas pedestal, a modest homage to the legendary building’s main tourist magnet. Upstairs, on a wall where the frieze had hung in 1902–03, Rockenschaub hung seven Plexiglas panels, a reference to the decorative niches below the frieze in the Beethoven exhibition. In 1993 at the 45th Venice Biennale, he filled another historic interior with scaffolding, a tribute to Josef Hoffmann in the Secession architect’s Austrian Pavilion (1934).[24]

As Rockenschaub intended, his Plattform (2012) was a respectful intervention and an art work in its own right, precise in its geometry. In the frieze, the “Choir of Angels” hovers in the last panel to sing Schiller’s “Ode to Joy,” the choral finale of the fourth movement of the Ninth Symphony; from the floor of the room the choir is mute (fig. 12). Seen from the yellow platform, the embracing pair in “The Kiss to the Whole World” came into focus within a prickly rose bower – planted in the painter’s mind perhaps by Margaret MacDonald – under the sun, the moon, and the gold pastiglia (fig. 13). On a quiet day, this close to Klimt’s frieze of humanity, the word from the chorus that ends the symphony was unmistakable – Götterfunken, spark of the gods.

Gegen Klimt: Die “Nuda Veritas” und ihr Verteidiger Hermann Bahr (Against Klimt: Nuda Veritas and her defender Hermann Bahr)

Österreichisches Theatermuseum, Vienna

Curators: Kurt Ifkowits and Andreas Kugler

May 10 – October 29, 2012

No catalogue

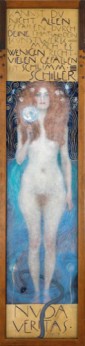

Not the Ninth Symphony, but the Eroica and other earlier Beethoven works come to mind at the Austrian Theater Museum. Since 1991, the museum has occupied the Palais Lobkowitz in Vienna. There the Symphony no. 3 in E flat major, Opus 55, was first privately performed in 1804 for Prince Franz Joseph Lobkowitz, to whom Beethoven had dedicated his radically new work; the composer allegedly had obliterated the earlier dedication to Napoleon after his hero had declared himself emperor. Three years later Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony also had its private premiere in what is now known as the Eroica Hall of the Viennese palace. The museum, created in 1975 as part of the Austrian National Library, has been incorporated into the Kunsthistorisches Museum since 2001.[25] Its collections include drawings, architectural and set models, photographs, posters, costumes, and props; in a category called quisquilia(Latin for odds and ends, or Italian for bagatelle) are some 2,000 objects of personal memorabilia, chiefly from the legacies of famous personalities in the Austrian cultural scene. Among those miscellaneous holdings is a work that has become the museum’s most valuable object: Gustav Klimt’s Nuda Veritas (fig. 14).

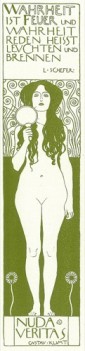

Klimt showed the picture in the fourth Secession show (March 18–May 31, 1899) under the title Die nackte Wahrheit (The Naked Truth; cat. no. 148). The nude figure had already appeared in a drawing for the third number of Ver Sacrum in 1898 (fig. 15). The quotation inscribed over the nude in the drawing – “Truth is fire, and to speak the truth is to shine and burn” – came from a novella by the German writer and composer Leopold Schefer (1784–1862).[26] In Ver Sacrum Klimt’s Truth had a pendant on the same page: Envy (Neid, representing the letter “N”), with a snake curling around her neck and a background pattern of thistles. Later that year in the second Secession exhibition (November 12–December 28, 1898), Klimt showed Pallas Athene (1898; Wien Museum), in which a miniature red-haired, frontal female nude holding a light appeared in the right hand of the goddess, a slot traditionally reserved for a winged Nike. Then in 1899 for Nuda Veritas, Klimt inflated that tiny painted figure to fit a canvas more than eight feet tall and not quite two feet wide, retaining the proportions of the Ver Sacrum drawing and inserting the snake from Envy. For his text above the nude, Klimt abandoned the fanatical sacrificial imagery suggested by the quotation from Schefer. In its place he inscribed over his now life-sized Truth a defiant epigram addressed by Friedrich von Schiller to the artist plagued by critics: “If you cannot please everyone with your actions and your artwork – please only a few. To please many is bad.”[27]

Gegen Klimt (Against Klimt), the deft anniversary exhibition at the Austrian Theater Museum, opened with a dramatic installation of Nuda Veritas (fig. 16). Through an opening between two panels came the first glimpse of the painting; on the panel to the left was a sentence of praise written by the prolific Austrian critic and successful dramatist Hermann Bahr when he first saw the picture.[28] At the Secession show Bahr admired – even more than Nuda Veritas – Klimt’s Schubert at the Piano, the now-destroyed supraporte painted for Nikolaus Dumba’s music room; he called it “the most beautiful picture ever painted by an Austrian.”[29]Nuda Veritas had hung almost unnoticed in the Klimt/Hoffmann show at the Belvedere during the winter of 2011–12. Given a room of her own at the Theater Museum, the painting, still in its original wooden frame of beech and fir with metal repoussé work by Georg Klimt, regained her polemical impact (fig. 17). Truth has dropped her veil and, standing between two luminous dandelions with a snake at her feet, holds her mirror up to the viewer like a Secessionist Statue of Liberty.[30] Klimt’s former colleague in the Künstler-Compagnie Franz Matsch had turned a similar concave mirror toward the viewer in his painting Katharina Schratt as Frau Wahrheit (1895; Bundestheater-Holding, Vienna); the Burgtheater star and friend of the emperor, however, was fully clothed as Mrs. Truth.[31]

Bahr, one year younger than Klimt, became known as the broker of modernism in Vienna soon after he settled in the city in 1891. From its beginnings in 1897 he proclaimed his support of the Secession; in April 1898 Bahr began giving Sunday-morning tours for the working class at the group’s first exhibition.[32] The word “truth” was so closely associated with Bahr’s writing at that time that some have wondered whether Nuda Veritas was not painted to order for the prominent litterateur. He bought the painting in 1900 for 4,000 Kronen, paying in four installments.[33] Klimt’s letters acknowledging receipt of the payments were among the documents selected from the museum’s Bahr archives for display in the two large rooms of the exhibition. After Bahr’s death in Munich in January 1934, his papers remained with his widow, the dramatic soprano Anna Bahr-Mildenburg.[34] She died in 1947, and in 1954 Klimt’s Nuda Veritas came with the bequest of her own and Bahr’s estates into the collections of the Austrian National Library.

Mining this rich treasure at the Austrian Theater Museum, curators Kurt Ifkowits and Andreas Kugler produced a focused show illuminating the intersection of Klimt and Bahr after 1897 (fig. 18). Bahr was a pro-Klimt member of the art council appointed in May1900 to advise the Ministry of Education during the controversy over Philosophy, the first of the University faculty ceilings. When Medicine, the second faculty painting, appeared at the tenth Secession show (March 15–May 12, 1901), Bahr defended the artist in a speech, originally intended as a reading in a series sponsored by the Concordia press society. He told the audience that Klimt didn’t need him as a defender, for like all great men, neither applause nor scorn could affect him. “It’s not about him,” Bahr said, “but about us. He isn’t threatened, but we are. Nothing can happen to him, but we will be the laughing stock of Europe.”[35]

The same impulse to demonstrate the absurdity of the violent attacks on the artist led him to write the foreword to an anthology of negative press reactions that appeared in November 1903. This little book, Gegen Klimt, lent its title to the 2012 exhibition (figs. 19 and 20). The idea was Kolo Moser’s, but the curators discovered during research for the show that Fritz Waerndorfer, a founder of the Wiener Werkstätte in 1903, had played a major role in compiling the book, along with Max Burckhard. One letter from Waerndorfer to Bahr explained: “Klimt knows nothing [about the book] and should know nothing.” Enlarged pages from Gegen Klimt lined the curving wall of the gallery at a comfortable height for reading in conjunction with archival material in vitrines. The handsome installation of the exhibition by Gerhard Veigel allowed the curators to convey a sense of the fun and fervor of the team producing the elegantly printed defense of the artist.

On the rear wall a photographic enlargement revealed a life-size Bahr, in a floor-length robe much like those worn by Klimt, standing near his desk in front of the totemic Nuda Veritas (fig. 21). Bahr had been so deeply impressed with the quality of “truth” in Olbrich’s Secession building that he commissioned the architect in 1899 to design his house. The following summer he moved into his new villa in the Vienna suburb Ober St. Veit, a part of Hietzing. Olbrich’s designs for the installation of Nuda Veritas in the writer’s study were exhibited in the show, along with other architectural drawings and photographs of the villa (fig. 22). Bahr took Olbrich’s furniture and decorations with him when he moved to Salzburg in 1912, but a door has survived in the house and was on loan to the show. The writer had framed his Klimt drawing Hexe (Witch) in the door, but took the sheet with him when he sold the house (fig. 23). From exposure to light Hexe has faded, compared to its vivid reproduction in the February 1898 Ver Sacrum. Another Klimt drawing of Maria (“Mizzi”) Zimmermann, who modeled for Schubert at the Piano and other pictures before 1903, was also part of the Bahr estate. Placed in a vitrine below the drawing in the first room with Nuda Veritas was a touching letter addressed to Bahr in1930 by the former mistress of the painter and mother of two of his sons. She described her connection to Klimt, her financial distress, and informed the owner of the painting that she had posed for the hands, feet, and hair of Truth.[36] Bahr wisely salvaged Olbrich’s mailbox when he moved, although it would have perhaps jarred with the Biedermeier façade of his new home at the foot of the Kapuzinerberg in Salzburg, Schloss Arenburg/Bürglstein (fig. 24). Anna Bahr-Mildenburg preserved it, however, along with everything else she bequeathed to Austria. Thanks are due to her, the writer’s first archivist, and to the curators who dug into many acid-free boxes to bring Bahr’s enthusiastic response to Klimt into the Theater Museum galleries for this absorbing show.

Klimt: Die Sammlung des Wien Museums

Wien Museum, Vienna

May 16 – September 16, 2012 (extended to October 7, 2012)

Catalogue:

Klimt: Die Sammlung des Wien Museums / Klimt: The Collection of the Wien Museum

Ursula Storch, ed. Foreword by Wolfgang Kos; essays by Storch, Marian Bisanz-Prakken, Brigitte Borchhardt-Birbaumer, Sophie Lillie, William M. Johnston, Kerstin Krenn, Georg Gaugusch

Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2012.

301 pages; 498 color illustrations; collection inventory; bibliography.

ISBN: 978-3-7757-3360-1 (German trade edition)

978-3-7757-3361-8 (English trade edition)

€49,80 ($63; £40)

With its single, important Klimt painting and two drawings, the Austrian Theater Museum mounted a distinguished exhibition, a small, sleek show that opened new perspectives on the early Secession period, Klimt’s defenders, and his critics. The Wien Museum, by contrast, boasts “the largest Klimt collection in the world” (12). In addition to over 400 drawings – 273 were in the bequest of Franziska Klimt, Georg Klimt’s widow, in 1944 – the municipal museum owns eight oils and some twenty portrait photographs (fig. 25). As a museum of cultural history, it also collects Klimt merchandise and took an ironic stance early in the anniversary year by launching a contest on Facebook to gather images of the “Worst of Klimt.”[37] Wien Museum Director Wolfgang Kos explains in a reflective foreword to the catalogue that the birthday celebration inspired a radical decision: they would show it all.

Working with the architectural firm BWM, curator Ursula Storch fit the entire collection into a single large room. The entrance foyer, adjacent to the area filled with drawings, had to be kept at a light level of no more than ten foot candles and consequently looked somewhat funereal. Visitors passed a row of black-and-white portrait photographs, the artist’s death mask, and a drawing made by Egon Schiele in the mortuary the day after Klimt died. With relief and recognition, the viewer arrived at a shroud: Klimt’s only surviving indigo-dyed linen smock, a gift to the museum from the painter Otto Trubel in 1964 (fig. 26). Most museum-goers proceeded around the corner into a cheery alcove to inspect a panoply of spotlighted souvenirs, although it was surely meant to be the final room of the show.

Storch divided the large room and the catalogue into ten thematic sections (fig. 27). Framed drawings made the outer walls a “paper zone” from floor to ceiling, with brochures for use in the gallery keyed to identifying numbers on the frames. Without using a brochure, visitors had only a wall text for each section to give them a general sense of what they were looking at, although drawings singled out as important had black frames, rather than white. Paintings and posters hung on black free-standing partitions in the center of the room. For her introductory essay to the catalogue, Storch assembled a valuable history of the city’s Klimt collection (12–21).[38]

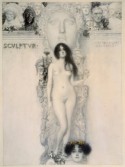

The earliest object acquired by the museum was a tiny drawing for a ball souvenir gift in 1892, donated to the city the following year (12, 24, cat. no. 3.42). The next acquisition came in 1901, when the publishers Gerlach & Schenk exhibited for sale at the Rathaus their collection of preparatory works for the series Allegorien & Embleme (1882–84) and Allegorien: Neue Folge(1895–1900). The Österreichische Museum für Kunst und Industrie (now MAK) showed no interest in buying these works, so the city wisely purchased the entire group (71). The collection included eleven Gustav Klimt drawings and paintings, among themLove (1895; cat. no. 2.19), his earliest combination of gold with a kissing couple, and Sculpture (1896; cat. no. 2.22), represented by a frontal Eve- or Venus-like nude (fig. 28). These works, both borrowed frequently for exhibitions, mark the beginning of a new period for Klimt.[39] Among the identifiable objects in Sculpture is a four-headed marble sphinx (second century A.D.) from the antiquities collection of the Kunsthistorisches Museum – it also appears in Music and Music II – and a bust of Dante recycled from the museum stairwell (1890–91), where, until the bridge was built during the Klimt Year, few would have noticed it.[40]

The next acquisition was in 1907: the prize-winning Auditorium of the Old Burgtheater (1888–89; cat. no. 4.1). Hanging at the far end of the room, the painting consistently drew more visitors than any other work in the show (fig. 29). After completing decorations for the stairwells of the new Burgtheater in 1888, Klimt and Matsch were commissioned by the city council to paint the old court theater on the Michaelerplatz prior to its demolition. Matsch took the view toward the stage, and Klimt the view toward the auditorium, filling it with hundreds of watercolor portraits of Ringstraße society. Modern Viennese gathered around the key sold with a heliogravure produced from the picture by court photographer Josef Löwy; they hoped to locate the actress Katharina Schratt, or Berta Zuckerkandl’s father Moritz Szeps, or the future mayor Karl Lueger (292, cat. no. 32). But the exhibition catalogue included something more enthralling: Georg Gaugusch and Sophie Lillie devised a new photographic key to the picture, using Löwy’s numbering and adding fifteen details of groups and short biographies of identified persons and how they were connected to one another (112–23). In one of the details, the reader can recognize, for example, the future Klimt collector Serena Pulitzer Lederer in a loge (fig. 30).[41]

A new development for Klimt was the revolt within the Künstlerhaus. In the spring of 1897 the rebel group founded the Secession.[42] Klimt was elected president in April, and about that time he made at least two sketches of a proposed exhibition hall (fig. 31). In the sketch now in the Wien Museum, Klimt envisioned the Latin words Ver Sacrum over the entablature of a cubic structure (cat. no. 5.5). On Olbrich’s completed building, the words appear on the façade to the left of the entrance, and the full name of the society over the doors was replaced by Hevesi’s stirring inscription. For the central area at the entrance, Klimt had indicated a triangular arrangement of three blank escutcheons, used by the Künstlerhaus and other artists’ societies to represent painting, architecture, and sculpture. Olbrich transformed them into a row of apotropaic gorgon faces, each with a golden label. Another gorgon grimaced on Athene’s shield in Klimt’s militant poster for the first Secession exhibition, hanging on the black central wall of the Wien Museum exhibition in two impressions: censored, to mask the nude Theseus, and uncensored (figs. 32 and 33).

Athene apparently lent her protection to the newborn Secession. The first exhibition was a resounding success, with many foreign artists sending works, including Max Klinger, Auguste Rodin, and Fernand Khnopff. In the second Secession show, inaugurating the new building on November 12, 1898, Klimt showed his first large square portrait, Sonja Knips (1897–98; Belvedere). He also honored the tutelary deity with the smaller, also square Pallas Athene (fig. 34). Klimt painted a Homeric gleaming-eyed immortal in golden battle gear with a “grim, gigantic gorgon” on her aegis; his brother Georg made the frame. Inspired by Jan Toorop and Khnopff, as well as by Homer, Klimt’s Secessionist figure was hailed by the critic Hevesi as “a Pallas of today, of her time, of her place, and of her creator.”[43]

Hevesi expressed the hope that the painting would end up in a public collection, and it did, more than half a century later. Its first owner was Fritz Waerndorfer, followed by two other private owners. Franz Gluck, then in charge of the municipal collections, acquired Pallas Athene from the Galerie Neumann, Vienna, in 1954, the year ground was broken for the museum building on the Karlsplatz. Gluck must have recognized the importance of this painting for the new museum, which he would serve as its first director from 1959 to 1967. The painting has become such a frequent flyer that Storch devotes a page of her introduction to a world map of its travels since 1985 (21).

Storch’s entry for Pallas Athene (cat. no. 5.4) includes a curious remark that has descended through the Klimt literature, without a source, since the late 1960s: “The painting was shown in the same year [1898] in the Salon d’Automne in Paris” (138). The first Salon d’Automne in Paris was in 1903, and it seems implausible that Klimt would show this important new picture abroad before exhibiting it at the end of 1898 in the second Secession show.[44] He did have at least one invitation to exhibit abroad that year. As Alfred Weidinger pointed out in 2007, Klimt wrote to James McNeill Whistler on December 13, 1897, to offer him honorary membership in the Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs. Whistler reciprocated by offering Klimt honorary membership in the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, soliciting works to show in London at their first exhibition, held in May 1898 at the Prince’s Skating Club in Knightsbridge.[45] Although Klimt’s name and address are in the catalogue index, Weidinger found no mention of any work in the show. But the following year, as Weidinger noted, Klimt sent Pallas Athene (cat. no. 109) and A Portrait of a Lady in Pink ([Sonja Knips] cat.no. 153) to the second exhibition of Whistler’s society, held in London in May–July 1899; both paintings were illustrated in the catalogue.[46] What, if anything, Klimt showed in Paris in 1898 remains undocumented, and Storch correctly notes that Pallas Athene, again with Sonja Knips, traveled to the Exposition Universelle in 1900. They hung in the Grand Palais with Philosophy, the first faculty painting. Mocked in Vienna, Philosophy won Klimt a gold medal in Paris (322).

A much-discussed archaic element in Pallas Athene is the background, where a tiny Heracles has grasped from behind a scaly white-bearded Triton struggling to free himself from the hero’s hold. In 1976 Marion Bisanz-Prakken was the first to identify Klimt’s source: an early chromolithograph by Eduard Gerhard of a scene on a black-figure hydria now in the Toledo Museum of Art (fig. 35).[47] She also noticed that a photograph in Ver Sacrum showed no veil wrapped around the feet of the prototype for Nuda Veritas in Athene’s right hand, suggesting that it was added after the exhibition.

The other star painting in the Wien Museum collection was given the most prominent place in the show. Portrait of Emilie Flöge stood in the middle of the room, an apotheosis of svelte Wiener chic (fig. 36). Storch remarks in her catalogue entry on the intriguing contrast between the realistic face in a stylized aureole and the gold-flecked dress, which, she points out, is too tight to be called reformed clothing, the trend in artistic circles in England, Belgium, and Germany (206). Fräulein Flöge didn’t care for the portrait, and Klimt sold it to the Niederösterreichisches Landesmuseum in 1908. When the city of Vienna became a province on its own in 1921, the painting became the property of the municipal collections.

Displaying the Wien Museum Klimts as an ensemble and the close hanging of 400 drawings yielded an understanding of Klimt’s working method that selective exhibitions do not. The experience was something like walking through the artist’s studio, bending now and then to pick up a sheet or two, and comparing a motif as it developed over time. Producing a catalogue of the museum’s Klimt holdings is undeniably an achievement, but a collection catalogue organized thematically and lacking an index would be more satisfactory online. The printed book has no list of donors, previous owners, or portrait subjects, something that in a searchable online catalogue would pose fewer problems. A single example is the drawing purchased in 1918 from the estate of Otto Wagner (13). Storch arouses interest by mentioning its title (Female Head) in her history of acquisitions, but it takes a determined reader to locate the ex-Wagner drawing as a study for the gorgons in the Beethoven Frieze (cat. no. 5.34). A simple cross-reference in Storch’s essay to its catalogue number would have smoothed the way. Other key essays – Bisanz-Prakken’s on the rarities among the drawings, or William M. Johnston’s addition of relevant new interpretations for Hevesi’s invented verb klimtisieren – also would have become more accessible with an index. Even unindexed, the frank approach to issues of restitution throughout the catalogue was welcome, and the museum’s series of panel discussions on responses to Klimt today delivered additional stimulation during the run of the show.

Die Textilmustersammlung Emilie Flöge (Emilie Flöge’s Collection of Textile Samples)

Österreichisches Museum für Volkskunde, Vienna (Austrian Museum of Folk Life and Folk Art)

May 25 – December 2, 2012

Catalogue:

Kathrin Pallestrang, Die Textilmustersammlung Emilie Flöge im Österreichischen Museum für Volkskunde

Foreword by Margot Schindler

83 pages; 54 color illustrations; checklist

ISBN: 978-3-902381-21-7

€ 23 ($28)

The elegant standing portrait of Emilie Flöge at age twenty-eight is a vivid permanent resident at the Wien Museum. Four hundred postcards sent by the allegedly incommunicative Klimt to Fräulein Flöge, his Lebensmensch, formed the core of the delightful show at the Leopold Museum: Up Close and Personal. The Austrian Museum of Folk Life and Folk Art unveiled another treasure in 2012, exhibiting much of its collection of textile samples from the Flöge estate (fig. 37). Selected for the exhibition and meticulously described in a catalogue by curator Kathrin Pallestrang were 201 of the Flöge collection’s 369 objects, mostly fragments of lace and embroidery from Western Slovakia. Comparable in number to her Klimt postcard collection, the textile samples include only a few entire pieces of clothing; those are mostly women’s bonnets meant to be tied under the chin with ribbons or bands and worn on the back of the head. Photographs by Dora Kallmus (Madame d’Ora) and others suggest that Flöge herself created and modeled a variety of modish hats, as well as dresses. The exhibition documents her parallel interest in the colors and patterns of folk art, in part, perhaps, as a source of inspiration, but also for re-use in her own designs.

Behind the first vitrines was an introductory wall panel with an enlargement of Friedrich Walker’s Lumière autochrome portrait of Flöge at the Attersee in 1913; Flöge’s dress has an insert of embroidery from Rybany, Slovakia (fig. 38). She displayed pieces from her collection in her salon on the piano nobile in the Casa Piccola, Mariahilferstraße 1b, opened in 1904 and decorated by Josef Hoffmann and Kolo Moser of the Wiener Werkstätte. A second wall panel illustrated the reception room with an enlarged detail of a photograph, noting that the designer ran the business in the Casa Piccola – Schwestern Flöge – with her sisters Pauline and Helene, the widow of Klimt’s brother Ernst, and later with her niece Helene Donner (fig. 39).[48]

The wall text explained that although Emilie Flöge herself made and wore the loose garments of reformed clothing, most of the salon customers opted for traditional styles. The Flöge sisters’ father, Hermann Flöge, had been a manufacturer of meerschaum pipes and a Protestant; that Emilie, a non-Jew, had to close the business in July 1938 was mentioned cryptically on the museum panel: “The clientèle, largely from the Jewish upper bourgeoisie, were no longer there.” She was forced to vacate shop and apartment, and little of the Wiener Werkstätte furnishings could be saved.

Displayed in a vitrine in the section entitled “Jugendstil” was a sample of labels designed by the Wiener Werkstätte to identify the firm’s products (fig. 40). A handsome belt (cat. no. 4.33), combining two strips of black-and-white embroidered cloth from Rybany with white lace fragments and six mother-of-pearl buttons, had a vitrine of its own as an example of an assembled object (fig. 41). The embroidered and lace pieces were identified in vitrine labels and each type of stitch or lacemaking technique was mentioned in the exemplary catalogue entries (figs. 42 and 43). Nearly a dozen embroidered bonnets, some trimmed with lace, were on view in the groups of complete objects (fig. 44). A silk bonnet with embroidered brim and broad silk ties with ruffles stood in the final Jugendstil section, suggesting the integration of handcrafted forms into contemporary designs (fig. 45).

Pallestrang’s catalogue essay points out that Flöge was not the only collector of folk art in Secessionist circles; other collectors included Josef Hoffmann and Alfred Roller’s wife Mileva.[49] Pallestrang also comments on the influence of Alois Riegl’s study in 1894, Volkskunst, Hausfleiß und Hausindustrie (18). The museum’s narrowly focused and well-presented show and its catalogue called attention to Flöge’s passion for colorful embroidered sleeves and bonnets, scraps of lace, and other handwork, an interest of Klimt’s companion that might otherwise have been forgotten during the commemorative events of the anniversary.[50] Emilie Flöge outlived Gustav Klimt by thirty-four years.

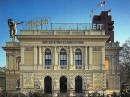

Ohne Klimt: Gustav Klimt und das Künstlerhaus (Without Klimt: Gustav Klimt and the Künstlerhaus)

Künstlerhaus, Vienna

July 6 – September 23, 2012

Curators: Peter Bogner and Patrick Fiska, with assistance by Holger Englerth

No catalogue; gratis brochure of wall texts in German and English.

Klimt and the Secessionists resigned in 1897 from the Künstlerhaus. A concise and thoughtful show held there in 2012 – aptly titled “Without Klimt” – celebrated, as a happy ending, the artist’s triumphant re-entry into the building in 1985 with the exhibition Traum und Wirklichkeit: Wien, 1870–1930 (fig. 46). “Dream and Reality” was organized by Robert Waissenberger, director of the Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien (now Wien Museum) and designed by Hans Hollein, who won the Pritzker Architecture Prize that same year. Between March 28 and October 6, the show drew a record-breaking 660,000 visitors into the building. For the exhibition in 1985, Hollein placed atop the Künstlerhaus a colossal golden figure of the female nude from Medicine. Inside, the Beethoven Frieze, set in Hollein’s replica of the original Secession gallery by Josef Hoffman, made its first public appearance since its purchase by the Austrian state in 1973. After the exhibition, the frieze moved into the new gallery constructed in the basement of the Secession.

The Künstlerhaus show in 2012 also documented another posthumous Klimt triumph in the shadow of National Socialism. All three faculty ceilings appeared for the last time in an exhibition managed by the Künstlerhaus: the painter’s eightieth-birthday retrospective in 1943, also the twenty-fifth anniversary of his death. Sponsored by the Gauleiter and Reich’s governor for Vienna, Baldur von Schirach, and organized by Bruno Grimschitz, director of the Österreichische Galerie under the Nazis, the exhibition took place in the former Secession building, renamed “Ausstellungshaus Friedrichstraße” and administered by the Künstlerhaus until 1945. With a hundred entries, including two segments of the Beethoven Frieze, seized in 1939 with the property of Serena Lederer, the exhibition was the largest display of the artist to date. Serena Lederer died in Budapest weeks after the show closed, and her paintings were transported to Schloss Immendorf. Among the finds in the Künstlerhaus archives selected by the curators for this fascinating display were photographs taken at the opening of Gustav Klimt in 1943 (fig. 47).[51] A framed copy of the catalogue was on view, with a surrogate for exhibition visitors to examine.

Ohne Klimt was mounted in the Founders’ Room (“Ranftlzimmer”) and a small adjacent room.[52] White panels masked the wainscoting and damask-hung walls where necessary, otherwise the traditional architecture served as an evocative setting for relating the story of the prestigious artists’ society in the years immediately before and after the Secession (fig. 48). The curators attempted to counter clichés about both sides in the quarrel that exploded within the Künstlerhaus in 1897. The opposition of the old versus the young, for example, was belied by the open-minded watercolorist Rudolf von Alt, the honorary first president of the Secession. On one wall hung Alt’s letter of resignation from the Künstlerhaus dated May 24, 1897, signed when he was nearly eighty-five (fig. 49).

One of the strongest voices of reform within the society before the Secession had been the former military officer Theodor von Hörmann. When the outspoken painter died in July 1895, the future Secessionists considered him a martyr to artistic freedom. In 1891, the year Klimt solicited and gained admittance to the society, and again in 1894 and 1895, he served on various exhibition juries and committees with his fellow members. Compared to Josef Engelhart, Carl Moll, and Johann Viktor Krämer, who had previously protested as individuals, Klimt was a moderate. Then, at the end of 1896, the society elected the conservative painter Eugen Felix as president by sixteen votes over the sculptor Edmund Hellmer. Dissent reached a point of no return, and a few months later the new group found a building plot for a separate exhibition hall (fig. 50). Visitors to the Künstlerhaus show could follow the events of the turbulent spring of 1897 through archival material. In this exhibition without Klimt, viewers had to content themselves by identifying his increasingly emphatic signatures on letters of protest or withdrawal. Other documents revealed that the elderly former Secessionists Moll and Krämer – both painters were born in 1861 – gratefully accepted invitations in 1942 to rejoin the Künstlerhaus.[53]

A corner of the Ranftlzimmer was dedicated to a larger group of absentees: women. Although they could submit works to annual exhibitions and to those of the Aquarellistenclub (Watercolor Painters’ Club), women were not admitted to full membership in the Künstlerhaus until 1951. The curators assembled a long list of female artists exhibiting in the society’s shows and displayed a poster by Heinrich Lefler for an exhibition of the Watercolor Painters’ Club, which accepted several prominent female artists as “corresponding members” (fig. 51).

One revelation from the outstanding Künstlerhaus posters selected by Peter Bogner for Ohne Klimt was the common symbolism among those artists who remained and those who withdrew. Lefler – still in the Künstlerhaus in 1898, although he would resign to form the Hagenbund in 1900 – used a frontal female head for his poster advertising the emperor’s forty-year Jubilee Exhibition; on her breast was a trio of ornamental disks representing painting, architecture, and sculpture (fig. 52).[54] As late as 1909 the Künstlerhaus poster for the annual exhibition depicted Athene (fig. 53). Most of the posters, like those for the Secession and the Hagenbund, deployed three empty escutcheons as symbols of the united arts (fig. 54). Josef Breitner confined the three shields to a red-and-white banner in his poster promoting the society’s fiftieth-anniversary exhibition in 1911; he depicted an armored equestrian figure in a blossoming meadow in front of the Künstlerhaus, using a visual vocabulary reminiscent of Klimt’s The Golden Knight in Nagoya (fig. 55, compare fig. 5 above).

For the Künstlerhaus contribution to the 2012 anniversary a few well-chosen artifacts were arranged in a very small space; the show nevertheless supplied pertinent institutional background on the evolving art world at the turn of the century. Without a single Klimt painting or drawing, this surprisingly dense exhibition about absence attracted a steady trickle of visitors, who patiently deciphered Kurrent script and read the complex labels. The chief document of the show, the Secession members’ final letter of resignation dated May 24, 1897, was written in the small, clear hand of Carl Moll; Klimt was the first to sign (fig. 56).

Jubiläumsausstellung: 150 Jahre Gustav Klimt (Jubilee Exhibition: 150 Years of Gustav Klimt)

Belvedere, Vienna

July 13, 2012 – January 6, 2013

Curators: Alfred Weidinger and Agnes Husslein-Arco

Catalogue:

Agnes Husslein-Arco and Alfred Weidinger, eds. Essays by Husslein-Arco, Weidinger, Christina Bachl-Hofmann, Dagmar Diernberger, Markus Fellinger, Michaela Seiser, Eva Winkler, Stefan Lehner, and Katinka Gratzer-Baumgärtner

Munich, London, New York: Prestel, 2012.

359 pages; 305 color illustrations, chronology of Beethoven Frieze, illustrated list of exhibited works

ISBN: 978-3-901508-92-9 (German edition)

978-3-901508-93-6 (English edition)

From the Künstlerhaus to the Upper Belvedere is short walk uphill or three stops on the D tram. Few, if any, tourists would have opted to see a show without Klimt, however instructive, before visiting the Belvedere’s opulent 150 Years exhibition during the ten weeks (plus a few days) that the shows overlapped. For Klimt the trajectory to the palace was relatively short. Only three years after May 1897, when he and his colleagues walked out of the wrathful meeting at the Künstlerhaus, came the initial purchase of a Klimt painting for the national museum. That first picture was After the Rain (1898; cat. no. 13), acquired by the Ministry of Education from the seventh Secession exhibition (March 8–June 6, 1900) for what was to become the Moderne Galerie (now the Belvedere). The delicious landscape, showing a flock of wet hens grazing in a meadow near fruit trees, remains in the Belvedere and appeared with the museum’s other Klimt paintings in the Jubilee Exhibition of 2012 (fig. 57).

This was not true of the second Klimt acquisition for the Moderne Galerie, purchased the following year from the Secession’s tenth exhibition (March 15–May 12, 1901). In that show, On the Attersee(1900; Leopold Museum, Vienna) had a prominent place adjacent to the second faculty ceiling, Medicine. Director Franz Martin Haberditzl of the Österreichische Galerie traded the landscape in 1923, claiming it had no importance for the museum; it passed through a series of private collections before Rudolf Leopold bought the painting in 1995 (cat. no. 47). Not only did the museum lose a Klimt landscape in 1923, but all his works on paper were transferred to the Albertina in a reorganization of the former imperial collections begun in 1919 by art historian Hans Tietze (8). Of the dozen drawings in the Jubilee exhibition, one sheet is in the Belvedere on loan: two studies for Medicine, recto and verso (337, 339–40). The museum also owns the small red sketchbook acquired in 1996 and displayed with Sonja Knips, who holds it in her left hand in her portrait (cat. no. 17). All the other drawings were borrowed for the show from private collections.

The exhibition catalogue, however, re-assembled sixty drawings from the Albertina in a bold musée imaginaire: “Gustav Klimt in the Belvedere, Past and Present” (31–277).[55] The large orange catalogue numbers 1–101 in this main section of the book refer to a fictive collection, had there been no trades, no museum reform, no fire in Schloss Immendorf, and no restitution of works looted from Jewish collectors. To learn which of those 101 objects actually were in the exhibition, the reader must turn to the illustrated list of works by artist at the back of the catalogue (322–57). This list includes cross-references to the orange catalogue numbers for twenty-three Klimt paintings and the important red sketchbook that Klimt gave to Sonja Knips.

Possession of the largest number of Klimt paintings under a single roof, as well as a commensurate in-house expertise, sanctions the audacity of this unusual catalogue. Few museums would place a historiographical essay up front; here the text by Christina Bachl-Hoffmann and Dagmar Diernberger is enlivened by ten full-page close-ups of selected books as objects (10–29). Mute on provenance in the past, the Belvedere has now published what it knows about the 101 Klimt works that have come into its custodial care over the years. The entries – signed by exhibition curator Alfred Weidinger, Marcus Fellinger, Michaela Seiser, and Eva Winkler – are well worth studying for more than provenance lists. Seiser’s entries on the three faculty paintings, for example, provide sequences of illustrations, as well as concise and readable interpretative remarks. Stefan Lehner and Katinka Gratzer-Baumgärtner contribute the most extensive and best-documented Beethoven Frieze chronology to date (305–15).[56] The catalogue lacks an index, and the English translation is ridden with typographical errors. It nevertheless rewards the patient reader with a good deal of new material and previously published information in a new shape.

The exhibition, although not as adventurous as the catalogue, provided many pleasurable moments. Seeing Klimt at the Upper Belvedere is inevitably a shared experience, and photographs in this review taken at the 2012 show suggest the social phenomenon of his mass appeal. Yet even at the height of tourist season and with no particular efforts at crowd control on the part of the museum, the seven rooms of the palace chosen for the Klimt celebration were spacious enough to permit concentrated viewing. Taking into account the baroque architecture, the designers masked it on three sides, constructing a black base and door frames, with white walls for the pictures and an upper zone for wall texts (fig. 58). The first room included works by the Künstler-Compagnie, the cooperative formed in the Kunstgewerbeschule (Arts and Crafts School) by the three young students Franz Matsch, Gustav Klimt, and his younger brother Ernst. This section of the show had traveled to Venice for the second venue of the Belvedere’s Klimt/Hoffmann show earlier in 2012, but had not been seen in Vienna.

One hanging included a painting by Ernst Klimt of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo (ca. 1890) and a recently discovered picture entitled Pan Comforting Psyche, dated 1892 and probably begun by Ernst and completed by Gustav after his brother’s sudden death in December of that year. Visitors lingered at this wall, taking in the pathos of this joint effort, comparing the irises in both compositions, then realizing that Gustav had used for his figure of Psyche the nude study from his student days hanging between the two canvases. Throughout most of the show, the palace’s eighteenth-century furnishings – mirrors and wooden panels, sometimes painted white and gilt-edged – could be seen on the window side of the rooms. This lent an accent to individual works and formed an effective contrast with the simple black document vitrines (fig. 59).

The second room (“Family”) offered a massive amount of wall text at a height that almost required binoculars (fig. 60). Visitors appeared willing to crane their necks to read the life dates for Klimt’s three illegitimate sons: Gustav Ucicky (1899–1961), the prominent movie director who made propaganda films for the Nazis; Gustav Zimmermann (1899–1976), who died one year after his mother “Mizzi”; and the short-lived Otto Zimmermann (1902–03).[57] Of great interest were repoussé copper frames and relief works by Georg Klimt, including a wonderful mirror on whose metal frame was spelled out the word VERITAS.

Room Three (“Secession”) included a lovely painting, new to most Belvedere visitors, by the Secessionist Rudolf Bacher (fig. 61). Italian tourists, recognizing the mausoleum of Caecilia Metella on the Appian Way in the background, paused to laugh at the misspelled title on the Belvedere’s label and noticed that Bacher had spelled it correctly on his canvas. That Sonja Knips was a constant target for audio guide users and tour groups in no way diminished the beauty of the staunch supporter of the Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte (fig. 62). Klimt’s red leather sketchbook depicted in her hand stood in a black vitrine, open to his early sketch of Nuda Veritas in its projected frame, next to the tiny snapshot portrait of himself he had enclosed in its pages.

Perhaps the most interesting installation in the room was the vitrine in front of a mirror set in a recently restored gilded frame (fig. 63). It contained five large index cards from the Federal Monuments Office recording the move of the Belvedere’s Medicine and the Lederer Klimt collection to Schloss Immendorf. Behind the displayed examples was a rack with reproductions of cards for all the destroyed works; visitors could learn on the back of these copies about the seizure of the collection and the fire. Regrettably, turning over one of those reproduced cards was the only way to obtain that information, and most museum-goers glanced at the card display and moved on. Of those who reached for a card, many failed to read the verso. The Belvedere had at least attempted to interpret for its large and diverse audience the tragic events in Serena Lederer’s apartment on the Bartensteingasse and the fire at Schloß Immendorf, but the message was lost to many visitors.

The fourth room of the show was called until recently the Makart Room, the only gallery capacious enough to hang the largest works by the nineteenth-century painter Hans Makart. Earlier it had held the colossal Rubens canvases purchased by Emperor Joseph II in 1776 from the outlawed and impoverished Jesuit order in Antwerp; they were moved in 1891 to the new Kunsthistorisches Museum. For the Jubilee exhibition, the room was thus ample enough to display Klimt’s best-known works – the “Golden Period” – and to accommodate the multitudes who came to see them (fig. 64). The epigraph on the long main wall was a quote from the diary of Alma Schindler (later Mahler) written on Wednesday, May 3, 1899, in Venice, about visiting San Marco with Klimt and her family. By the weekend Klimt had been summarily ordered back to Vienna by Carl Moll, Alma’s stepfather, ending an escalating flirtation with the nineteen-year-old beauty. Alma reported seeing the golden shimmer of the mosaics and talking with the painter a great deal: “He riveted me totally,” she wrote, “but offended me with his brutality.”

Allowing Alma to narrate Klimt’s first encounter with the mosaics of San Marco in the gallery dedicated to the golden period was a clever idea, and the paintings Judith (1901) and Salome (1909) on this wall nicely bracketed the time frame. Judith had been sent to Venice earlier in 2012 to hang with Salome as an attractive supplement to the Klimt/Hoffmann show, and Ca’ Pesaro lent Salome to Vienna for the remainder of the year. Between the two pictures, Egon Schiele’s Embrace (1917) dominated the wall. The bare male back in the late Schiele referred obliquely to the other embracing couples in the room. It is not listed in the catalogue checklist, suggesting a last-minute idea. Cardinal and Nun(Caress; 1912; Leopold Museum), Schiele’s dark parody of The Kiss, stripped of its gold, would have been a more challenging juxtaposition.

Weidinger points out in his excellent catalogue entry for Judith (cat. no. 48) that the Swiss artist Ferdinand Hodler bought the painting from the tenth Secession show in 1901; it entered the Belvedere collection in 1954, acquired from Hodler’s second wife, Berthe Hodler-Jacques (fig. 65). The entry illustrates two relevant pages in the red sketchbook given to Sonja Knips, one a study for the frame executed by Georg Klimt. Weidinger also illustrates a Lachish relief from Nineveh, the type chosen by Klimt as authentic Judaean vegetation for the background to Judith’s triumph. The curator notes as well the immediate recognition in Vienna of the biblical heroine’s resemblance to the star soprano Anna von Mildenburg, later the wife of Hermann Bahr.

Both short ends of the large gallery were entirely masked by black panels. At one end hung the last segment of the Beethoven Frieze: Embrace, as it is called on the label, or Ideal Realm, as captioned in the catalogue (fig. 66). In her newspaper review of 150 Jahre, Almuth Spiegler, the alert art critic for Die Presse, chided the museum for failing to mention on the wall label that this was actually a segment of the 1984 copy; the Belvedere later appended that information to the label. Approaching the dark wall, viewers seemed to respond to Schiller’s invocation in the “Ode to Joy”: “Be embraced, you millions.” Then they turned from the plaster frieze segment to the more familiar, clothed version of Klimt’s embrace. It glimmered, as Alma Schindler said of the San Marco mosaics, at the opposite end of the room (fig. 67).

Also glimmering at the press opening were fifty iPads with an app installed for the show, the first time an Austrian museum had produced an exhibition app. The devices were available to the public for a fee, but by summer’s end had proved to be problematic to use. The sound would fail, or the sequence would get stuck on one painting, distracting the user who then had to return to the ground floor and stand in line to trade the iPad for an audio guide. For the Josef Lewinsky portrait, for example, there was little added value on the iPad; a short film offered glimpses of the Künstler-Companie’s Burgtheater murals and a brief recitation from Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s Clavigo (fig. 68). The iPad films, credited to Timo Novotny, with a movie and soundtrack for each of the major Klimt paintings, were fake documentaries, appealing perhaps to fans of Bo Widerberg’s Elvira Madigan (1967).

For most viewers, no peripheral annoyances could spoil the magic of standing in front of Lovers (Kiss; cat. no. 73). The Belvedere has reverted to the original title used at the Kunstschau in 1908, where the work was purchased for the gallery in an unfinished state by the Ministry of Education; the picture was delivered and inventoried in the summer of 1909. Its price of 25,000 Kronen, described oddly on a wall text as “exorbitantly high,” seems well worth it, given how many busloads of visitors enter the Belvedere specifically to see the world-famous picture. Klimt sold Portrait of Emilie Flöge in 1908 to the Niederösterreichische Landesmuseum for 12,000 Kronen, and his fee for the three faculty paintings, repaid in 1905, was 30,000. Weidinger’s illustrated catalogue entry is suggestive, linking Klimt’s meadow to the cliff in a painting by Karl Mediz, The Icemen, and, less surprisingly, to Edvard Munch and Rodin.

After gazing at Lovers, clearly the apex of the show, viewers often revisited the room. A vitrine of acquisition documents could not entirely satisfy the need, not so much to know more, but to feel more. For some, an inchoate malaise set in, something like a phantom limb pain. The severed limb, of course, was Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907). The Belvedere’s co-star with Lovers until it was returned to its rightful owners in 2006, the painting is known vaguely to many because of the price Ronald Lauder paid the Bloch-Bauer heirs to acquire it for his Neue Galerie in New York. In the exhibition catalogue’s fictitious collection – “the way it was” museum – Adele Bloch-Bauer (cat. no. 72) took her proper place just before Lovers, sumptuously illustrated in her original frame (198-203).

Perhaps unconsciously shaking off this golden ghost, weary tourists tended to hurry through the final three rooms. Entering the fifth room, the viewer was momentarily startled by the hypnotic stare of the publisher Eduard Kosmack, the subject of a misplaced Schiele portrait. A dead sunflower connected the figure vaguely with the theme of the room: “Landscapes ” (fig. 69). A list of summer vacation spots on the wall and the suitcase of Emilie Flöge in a vitrine complemented a harmonious sequence of six square Klimt landscapes.[58] A square Monet, Garden at Giverny (1902) in a gilded frame, added little to an understanding of Klimt’s motifs (fig. 70). In the sixth room (“Women”), the majestic Fritza Riedler (1906; cat no. 67) reigned in her armchair portrait, seen in reverse in a magnificent gold-framed mirror on the Belvedere palace wall (184). Even her reflection was stronger than the two late, unfinished oil portraits on an adjacent wall next to Adam and Eve (fig. 71). Amalie Zuckerkandl could be appreciated in part as a drawing, and the painted blouse of Johanna Staube had a real double in a vitrine; Martha Alber designed both garments’ Wiener Werkstätte fabric called “Leaves” (ca. 1915).

Quietly displayed in this room was the biggest surprise of the show: a cache of hitherto unknown love letters from Klimt to Emilie Flöge (fig. 72). Four were furtive, addressed to Emilie under pseudonyms and mailed in care of general delivery (poste restante) to various post offices in Vienna; two were sent to her holiday lodgings in Styria; and a seventh, undated and less intimate, was sent to her at home. Located in a private collection by Belvedere Director Husslein and transcribed in the catalogue (summarized for the English translation), the letters required another electronic device to be deciphered in the gallery (281–91). Near each letter was a QR code permitting visitors with smart phones to read these private texts.

Klimt’s first letter in this group was dated November 18, 1895, and the last dated letter was written in Florence on April 27, 1899, just before the painter traveled to Venice with Carl Moll and family. This intimate correspondence appears to have ended abruptly, although Klimt vacationed with the Flöge family in August 1899 near Salzburg. That their warm relationship continued was clear to those who bent in fascination over the nearly 400 pneumatic card letters, picture postcards, and notes on view at the Leopold Museum.[59] Whether Emilie heard in May 1899 from others traveling with the artist in Italy about his pursuit of Alma Schindler, or whether she knew that Marie Ucicky gave birth to the baby Gustav on July 6, 1899, is speculation. What can be proven, thanks to a terse card letter in the Leopold Museum show, is that Klimt expected Emilie to meet him at the Raimund Theater at 7:15 p.m. on July 6, the day his first son was born. The newspapers reveal the play for which Klimt had gotten tickets: the Raimund that evening at 7:30 was performing Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts, a drama about inherited syphilis.[60]

The seventh and final room was called “The End” (fig. 73). The only Klimt painting on the wall was The Bride, an unfinished work photographed on an easel in the Hietzing studio after Klimt died (297–9). On each side of The Bride were Schiele works from the Belvedere collection, Family (1918) and Death and the Maiden (1915). Anton Hanak, a Secessionist sculptor who planned an unexecuted monument to Klimt in the 1920s, was present with a marble, The Young Sphinx (1916). With memorial steles holding death announcements for Klimt, Schiele, and Kolo Moser, the room was a funerary chapel for what was called in a wall text, “the fateful year” 1918.

The Belvedere exhibition path began with a vigorous climb in the first three rooms, reached a peak in the dramatic chiaroscuro setting of Lovers, and ambled toward the grave in Hietzing cemetery in the last three rooms. The show turned into something of a rehearsal for 2018, when the “fateful year” commemorative exhibitions will take place. Emilie Flöge, the naiad of the Attersee depicted by Klimt as his partner in Lovers, became a capable manager in the Mariahilferstraße, kept a dog called “Boy,” and drove a convertible. She and her niece saved for posterity the artist’s birthday wishes, picture postcards, and his Wiener Werkstätte gift brooches. At the Belvedere show, Flöge appeared in disguise as Klimt’s recently acquired Sunflower (1907; cat. no. 71) and at the artist’s side in a tintype (1899); otherwise she was represented by her suitcase, fitted out for travel, and a role in the iPad mini-dramas. A small oil sketch from her estate, Beech Forest (1903; private collection), also hung in the exhibition (181).

The astonishing find of the love letters gave those who could read them a new glimpse of the relationship. For Emilie’s twenty-second birthday in August 1896 Klimt copied out a dozen lines about Petrarch’s Laura from an eighteenth-century poem. Drawing a winged heart pierced with a sword above the poem, he apologized for not writing the lines himself and gave proper credit to Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock. Klimt fussed about rainy weather, about his dull pen or running out of paper, and about his fellow passengers on trains, addressing Emilie as “child,” “little one,” or “ma gazelle.” Fräulein Flöge came to life as the recipient of these letters, although she was a more active presence in her rejected portrait at the Wien Museum. The postcards and her collection of Slovakian bonnets and embroidery scraps gave further shape to the woman who was Klimt’s Laura.

Positive comments on the Klimt Year often use the metaphor of a concert or a mosaic. The eleven exhibitions added up to a richer, more nuanced view than a single blockbuster would permit. Each institution brought its own material into a raking light and gave its own slant to the Klimt story. Eight new catalogues – sadly, none of them with indexes – contain dozens of essays, for which specialists gathered colorful tiles to add to the mosaic. Many of the essays were outstanding, and even old Klimt hands – Marian Bisanz-Prakken, Rainald Franz, or Alfred Weidinger – came up with new insights as they re-examined the works from a different perspective. Particularly memorable voices in the polyphony of 2012 were Sophie Lillie’s essay in the Wien Museum catalogue on how each age creates its own Klimt or Franz Smola’s poetic epitaph (“Klimt and the Younger Generation”) for Up Close and Personal at the Leopold Museum (296–303). Some critics have wondered what Klimt would think of his birthday celebration. If interviewed, he might well repeat his much-cited utterance at the Westbahnhof on December 9, 1907, as Gustav and Alma Mahler left Vienna for New York. “It’s over,” Klimt is reported to have said, as their train pulled out.

Jane Van Nimmen

Independent scholar, Vienna, Austria

vannimmen[at]aon.at

The author is grateful to Atelier Hans Hollein, Manfred Horvath, and the Wien Museum for granting permission to use photographs. The following press officers and curators have been exceptionally helpful in supplying illustrations and other material: Andreas Kugler, Österreichisches Theatermuseum; Patrick Fiska and Nadine Wille, Künstlerhaus; Peter Stuibel and Barbara Wieser, Wien Museum; Klaus Pokorny and Anna Suette, Leopold Museum; and Maximilian Kunz and Veronika Werkner, Belvedere.

[1] The first of the Belvedere’s two exhibitions, Gustav Klimt / Josef Hoffmann: Pioniere der Moderne / Pioneers of Modernism, closed in March and moved in altered form to a second venue at the Museo Correr in Venice. The exhibition Gustav Klimt im Kunsthistorischen Museum closed in May, but the Klimt bridge built to span the museum stairwell remained open until the end of the year. Gustav Klimt: The Drawings closed at the Albertina in May to proceed to its second venue, The J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, under the title Gustav Klimt: The Magic of Line (July 3 – September 23, 2012). For a review of the earlier Klimt exhibitions in Vienna during Klimt year, see the Autumn 2012 issue of this journal.

[2] See Sophie Lillie, Was einmal war: Handbuch der enteigneten Kunstsammlungen Wiens(Vienna: Czernin, 2003), 656–71.

[3] The replicas and an explanatory panel were installed at the university in conjunction with an exhibition on art scandals – Die nackte Wahrheit – held at the Leopold Museum in Vienna and the Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt in 2005.

[4] The large central panel of the ceiling (The Victory of Light over Darkness) and the spandrels are the work of Franz Matsch, whose Theology, the fourth faculty painting for the ceiling, can be seen by appointment in the offices of the Faculty of Catholic Theology.

[5] The excellent Leopold Museum catalogue gave a full account of the fate of the faculty pictures; see Franz Smola, “University Paintings, 1894–1907,” Klimt: Up Close and Personal, exh. cat. (Vienna: Brandstätter, 2012), 183–91. The Lederer collection also featured in the Belvedere Jubilee exhibition and catalogue discussed below.

[6] Still an indispensable source on Klinger, Klimt, and the exhibition as a whole is Alessandra Comini, “Vienna’s Beethoven of 1902: Apotheosis and Redemption” in her remarkable The Changing Image of Beethoven: A Study in Mythmaking, New York: Rizzoli, 1987, chapter 6. A revised paperback edition with a new foreword by Comini was published in 2008 by the Sunstone Press in Santa Fe. See also Comini’s essay “The Two Gustavs: Klimt, Mahler, and Vienna’s Golden Decade,” in Renée Price, ed., Gustav Klimt: The Ronald S. Lauder and Serge Sabarsky Collections, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel, 2007), 32–53.

[7] See Marian Bisanz-Prakken, “Josef Engelhart und der 'Heilige Frühling’ der Wiener Secession,” in Erika Oehring, ed., Josef Engelhart: Vorstadt und Salon, exh. cat. (Vienna: Wien Museum / Brandstätter, 2009), 43–44.

[8] The first Secession show was held in March–June 1898 in rented galleries at the Horticultural Society building; Olbrich’s new building was still under construction. Among those attending the opening on March 26 was the American writer Mark Twain. Unconvinced perhaps by Klimt’s hour-long tour on April 5, 1898, Emperor Franz Joseph I made no purchases from the exhibition.

[9] The Moderne Galerie opened in the Lower Belvedere on May 7, 1903. For a fine essay on the evolution of the various versions of Rodin’s portrait bust, see Sylvie Patri, “Henri Rochefort’s 'romantic mask’: Rodin’s Portrait of Henri Rochefort,” in Agnes Husslein-Arco and Stephan Koya, eds., Rodin and Vienna, exh. cat. (Munich: Hirmer, 2010), 102–17.

[10]Berta Zuckerkandl was the daughter of the liberal newspaper owner Moritz Szeps. Her sister Sophie was married to Paul Clemenceau, younger brother of the Dreyfusard Georges Clemenceau, who had been elected to the French Senate in April 1902. On Rodin’s visit to Vienna, see Berta Zuckerkandl-Szeps, My Life & History, translated by John Summerfield (New York: Knopf, 1939), 180–81.

[11]Ludwig Hevesi, “Auguste Rodin in Wien” [dated June 8, 1902] in Acht Jahre Sezession (sic) (März 1897–Juni 1902): Kritik – Polemik – Chronik (Vienna: Konegen, 1906), 394–7. The eight years of the Secession in Hevesi’s title are those from the founding meeting until Klimt and his group seceded from the Secession in June 1905.