The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Il était une fois...l'impressionisme: Chefs d'œuvre de la peinture française du Clark / Once Upon a Time...Impressionism: Great French Paintings from the Clark

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal

October 9, 2012 – January 20, 2013

Previous venues:

Palazzo Reale

Milan, Italy

March 2 – June 19, 2011

Musée des Impressionnismes

Giverny, France

July 12 – October 31, 2011

CaixaForum

Barcelona, Spain

November 18, 2011 – February 12, 2012

Kimbell Art Museum

Fort Worth, Texas

March 4 – June 17, 2012

Royal Academy of Arts

London, UK

July 7 – September 23, 2012

It will also travel to Japan, China, and South Korea in 2013–2014.

What is at stake in the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute’s re-branding of itself? The exhibition and catalogue of nineteenth-century French art from the Williamstown-based institute that is currently traveling to three continents presents a new history to unsuspecting visitors: Sterling Clark, founder of the eponymous institute, was an autonomous collector who selected and acquired works with complete independence. What happened to his wife Francine? Anyone who has visited the institute and has seen her name on the building, or who reads the exhibition’s didactic labels will see artworks identified as “Acquired by Sterling and Francine Clark in 1919” or 1929 or 1953 or any one of the other active years in their over thirty-five year history as leading collectors of French art in North America (fig. 1). These visitors will be surprised and dismayed by the re-presentation of the Clark in the current exhibition that has egregiously misconstrued the history of its founders.

In the recent iteration of the exhibition at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Montreal, visitors were confronted by an introductory panel entitled: “Mr. Anonymous. The Collection of Robert Sterling Clark ” (fig. 2). The text then continued to offer evidence that it was, in fact, not just his collection: “Art aficionado, shrewd negotiator, as independent in life as he was in his tastes, this thoughtful and reserved man selected the works himself, subject to the only opinion he would take into account— that of his wife, Francine.” Indeed the wall on the other side of the entrance to the exhibition notes the institute’s full name and establishes a tension in the narrative constructed for the history of the collection that permeates the installation of the exhibition and its catalogue (fig. 3). While it may be admirable that the exhibition organizers want to laud the Clarks as collectors who acquired works of great quality without relying on dealers or professional advisors, as did other American collectors, such as Isabella Stewart Gardner (Berenson) or Henry and Louisine Havemeyer (Cassatt), the marginalization, and at times complete negation, of Francine’s contribution is a highly charged and, one can only hope, controversial misrepresentation of the history of the Clarks’ collection and their aspirations for their institute. The dissimulation of the Clarks’ collection is entirely in tension with the evidence provided by primary sources and yet the two principal essays in the catalogue are entitled “Sterling Clark as Collector,” (James A. Ganz) and “Redefined Domesticity: Sterling Clark’s Aesthetic Legacy” (Richard R. Brettell). Before the misconstrued historical evidence has an opportunity to have any lasting impact, this review seeks to highlight the evidence of Francine’s contributions and argues that the scholarship will only be accurately understood if reframed as “Sterling and Francine Clark as Collectors,” and “The Clarks’ Aesthetic Legacy.”

Fifteen years ago I published an essay “Private Art Collections in Pittsburgh: Displays of Culture, Wealth, and Connoisseurship,” that examined art-collecting couples such as the Fricks, Peacocks, Carnegies, Porters, and Lockharts, who were important figures in America’s “Gilded Age” of art collecting.[1] The evidence I encountered on the significant roles women played in the formation of family art collections in Pittsburgh led me to challenge the limited framework within which the English language had been used to describe the art collections of couples. There is a significant difference in the meaning(s) embedded in the semantics of the following: Frick’s collection or Clark’s collection as compared to writing the Fricks’ collection or the Clarks’ collection. Since working on this material starting in 1993, I have retained an astute eye for the varied ways in which writing on art collecting within the discipline of art history re-inscribes and reinforces hierarchies and engenders the history of collecting.[2] The presentation of the Clarks’ collection in the current traveling exhibition suggests we have much more work to do to dismantle the patriarchal framework of our discipline and its scholarship.

The Clarks met in Paris and Ganz quite rightly introduces Francine Clary as an actress of the Comédie-Française, where she debuted in 1904 after graduating from the Paris Conservatoire. Ganz suggests that while the early circumstances are unclear, a strong relationship formed between Sterling and Francine by 1911 when they were taking all their meals together and Sterling’s youngest brother witnessed Francine sometimes spending the night. While Sterling and Francine maintained separate homes until their marriage in 1919, they happily negotiated through a less than usual domestic arrangement in the early twentieth century. These highly personal, biographical details might not usually be significant; however, they are important in this context for two reasons. First, the earliest documented acquisitions date to February 1912 after Sterling purchased a Second Empire hôtel at 4 rue Cimarosa, in Paris’ elite sixteenth arrondissement, and thus the evidence suggests that all art purchases postdate the beginning of Sterling’s relationship with Francine. Yet, quite inexplicable to most museum-goers following the skewed introductory panel to the Montreal exhibition that identifies only “Mr. Anonymous” as the important collector in the couple, the didactic panels next to each painting and the catalogue entries parse out the acquisition history with 1919 as the unexplained breaking point: works such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Girl Crocheting are cited as “Acquired by Sterling Clark, 1916,” and Constant Troyon’s Gooseherd as “Acquired by Sterling and Francine Clark, 1919.” Catalogue readers will learn that the couple married in June 1919. Indeed, consulting broader sources, such as Nicholas Fox Weber’s family biography from 2007, The Clarks of Cooperstown, we learn more of the couple’s pre-marital conception of the domestic objects they acquired. In June 1912, a Steinway grand was delivered to a “Madame Clark” on rue Cimarosa, and in 1914 Tiffany’s delivered silver coffee cup holders to “Madame R. Clark” at the same address.[3] What seems inexplicable is that Weber cites his source as a publication of the Clark Art Institute from 2006, a catalogue essay that is in fact the unabridged work of Ganz from which the shorter essay for the traveling exhibition catalogue was derived.[4] Brevity is certainly required for exhibition catalogues intended for a broad audience at a reasonable price, however the result of eclipsing Francine, consciously intended or not, remains highly charged. Some art historians may perceive a division between objects acquired for domestic “use”, such as a piano and coffee cup holders—although irrefutably luxury objects with the names Steinway and Tiffany attached—however those whose methodologies are informed by more interesting approaches to the history of collecting would likely conclude that “Madame Clark” was a part of the decision-making process for all objects entering the domestic space, including those that might be categorized as “high art”, if one wanted to maintain such conventional divisions.[5]

Indeed, deconstructing traditionally-minded thinking informs the second reason why it is necessary to take account of biographical details at the origin of the Clark collection and that is Francine’s socio-economic background. The construction of Francine as an intellectual lightweight prevails in the catalogue of the current exhibition as well as the Clark Institute publication from 2006 and a persona is also shaped for Francine by a photograph in which she is dressed in a confection of the Paris stage (ca. 1900), an illustration in both publications. In fact, the catalogue from 2006 summarily diminishes Francine’s contribution to the collection by citing two paintings, by Émile Friant and Joseph-Louise-François Lepine, the only works billed to Francine rather than Sterling, as suggesting “a taste for charming images of Parisian life of the late nineteenth century that would come to be associated with Francine’s influence on the couple’s art collection.”[6] Ganz fails to elucidate how exactly this association occurred.

Francine’s background and lack of economic clout in the relationship seem to be central to efforts to marginalize her significance in the formation of the collection; and these are the same factors that Weber identifies as the sources of tension between Clark siblings over inheritance matters. Born in Paris in 1876 (thus one year older than Sterling), Francine was of Polish Catholic heritage and was raised by her single mother, Françoise Modzelewska, who supported them working as a dressmaker. The pattern of conceiving children outside marriage appears to have continued when Francine gave birth to her only child Viviane in 1901. In truth the evidence is unclear: Viviane’s father died in 1903 and is considered the likely source of the “Clary” portion of Francine’s name, but she signed up as “Mlle” when she joined the Comédie-Française in 1904.[7] They may never have married, or perhaps a young woman was perceived to have greater advantage launching a career on the Paris stage if she was regarded as single and without domestic responsibilities. Certainly just as important as her status as a single parent is the absence of a father’s name on Francine’s own birth certificate. Thus Sterling chose to build his life with a single mother whose cultural and economic background was vastly different from his own. Francine’s position within the Clark family was precarious at best, a point exacerbated by the fact that she and Sterling did not have their own children. Viviane’s status as Sterling’s stepdaughter and potential heir remained a point of contention within his family.[8] Visitors to the exhibition in 2011–12, or readers of the catalogue, might understandably conclude that Francine was a single-mother of lower social class who flirted with a career on the stage until she secured her future by marrying a wealthy man.

However, if one looks to earlier exhibitions and publications coming out of the Clark Institute, such as Master Drawings: Sterling and Francine Clark as Collectors, curated by director emeritus David S. Brooke in 1995, or A Passion for Renoir: Sterling and Francine Clark Collect 1916-1951, curated by Steven Kern in 1996, one is immediately struck by a quite different framing of the history of the Clark collection.

In his introduction to the Master Drawings catalogue, director Michael Conforti wrote: “One of the finest of the collections Sterling and Francine Clark left to the Institute which they opened in 1955 is a group of old master and nineteenth-century drawings. This collection was begun in Paris in 1913 and added to over the next four decades of their lives…the quality of Mr. and Mrs. Clark’s original collection has only rarely been rivaled by recent acquisitions.”[9] In this context Conforti handles the pre-marital origins of the collection in an inclusive manner, whereas in his foreword to the 2011 catalogue Conforti separates and distinguishes Sterling in his presentation as “A professional explorer, horse-breeder, and art connoisseur,” who “trained his eye by visiting galleries, attending auctions, and developing relationships with art dealers—most notably the Durand-Ruel family.” But concedes that “He also relied heavily on the opinion of his wife, and quotes from Sterling’s diary in which he describes Francine as 'an excellent judge, much better than I at times,’ and refers to her a his 'touchstone in judging pictures’” (xiii). Brooke repeats this same “touchstone” quote in his essay and notes that a peak year in the formation of the Clark’s drawing collection was 1919, the year of their marriage.[10] Brooke also states: “Nearly four hundred drawings were acquired by Robert Sterling Clark and Francine Clark over a period of some forty years. The collection seems to have been assembled largely for personal pleasure, without any master plan or desire to create a historical survey. In general it follows the same outline as does the painting collection, with relatively few older masters and a particular focus on the nineteenth century and on France.”[11] Brooke’s inclusive approach is not entirely consistent and there are various slips (perhaps heavy-handed editing) such as “In the early years of Clark’s collecting…”[12] However his presentation is largely successful and accurate: “While the Clarks’ major drawing acquisitions of the 1920s and 1930s were fewer…It was in this period between the wars, following a focus on important paintings in the mid-1930s, that the Clarks bought the Mary Cassatt pastel Child with Red Hat, a Claude Monet charcoal of Rouen, and three circus drawings by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. The last were chosen by Mrs. Clark, as Mr. Clark noted in his diary: '[The dealer] produced six excellent colored drawings of scenes at the circus—they were so good I phoned Francine…She chose the three I thought she would like and I bought them.’”[13] Brooke concludes, “The Clarks’ collection of drawings—as that of their paintings—was clearly a labor of love. They collected what they liked personally, freely indulging themselves in their favorites.”[14] Thus the well-respected former director of the Clark Institute declares the painting acquisitions as formed by the couple, just as he documents for the drawings.

In Conforti’s introduction to A Passion for Renoir: Sterling and Francine Clark Collect 1916–1951, he states “Steven Kern explores the early-twentieth-century taste for Renoir through an analysis of the extensive diary entries of Robert Sterling Clark, who with the constant and much valued advice of his wife, Francine, collected some of the finest of Renoir’s works.”[15] Kern writes, “While it is true that Sterling did not rely on outside advisers while forming his collection, Francine was an exception, and the documentation of her importance is found throughout this diaries. Virtually not a single painting was purchased by Sterling after about 1920 without the opinion of Francine”.[16] Kern makes particular note of the Clarks’ acquisition of Jane Avril by Toulouse-Lautrec, a work Francine declared a “chef d’œuvre” and the couple returned to the dealer to buy.[17] Interestingly Ganz reframes that same quote and concludes “Evidently such strong advice from Francine was rare, as the episode caused Sterling to comment: 'Never saw Francine more enthusiastic about a picture!’” (16). History is of course rewritten through the eyes and writing of the one examining the primary documents and Ganz incorrectly skews the evidence. To declare a work a “chef d’œuvre” as Francine does, requires a depth and breadth of knowledge, as well as a confidence. That Francine was never “more enthusiastic about a picture” does not mean her strong advice was rare, it means she was particularly impressed by this one work. Unfortunately, Kern includes in a footnote rather than in his principal text what is perhaps the most impressive evidence of Francine’s skills as a connoisseur beyond the primary source of Sterling’s diaries, and that is the perspective of Norman Hirschl, retired director of Hirschl and Adler Galleries and former manager of the John Levy Galleries which the Clarks regularly visited. Hirschl states that Francine always acquiesced to Sterling with regard to the American works they acquired, but that she led the discussion when a French painting was presented.[18] Sterling might see a work on his own at a dealer’s, such as he did Renoir’s Still Life of White Roses at Wildenstein’s, but his regular practice was to return with Francine before buying it. Their custom of making a final decision together meant they sometimes risked a work going to another collector, as was the case with this particular painting (15). Works were also often acquired conditionally and hung in the couple’s home as they made their final decision. Sterling’s need for Francine’s approval of rare purchases made when she was not present is apparent in his diary entry concerning Renoir’s The Girl with a Fan, about which he states “Francine was delighted with it and said I had done right” (15). Evidence ranging from the Clarks’ acquisitions of Goya (“To Knoedler’s…Francine and I agreed we must buy Goya,” to a Renoir nude they decided over lunch “would probably be tiresome” suggests that some scholars are misrepresenting the primary sources of the Clarks’ collection and, since the more thorough scholarship of the mid-1990s, have reframed the history of the collection and eclipsed Francine.[19]

It does not minimize Sterling’s role in the formation of the collection to acknowledge Francine’s significance. Indeed Sterling himself chose to do this in September 1953 when he opted to change the name of the institution from its original conception in 1950 as the “Robert Sterling Clark Art Institute” to the “Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.” One month after the ceremony marking the laying of the cornerstone in Williamstown, Clark wrote: “It is a particular gratification to me that the Institute…bears not only my name but also that of Mrs. Clark. Her constant enthusiasm for the Institute’s objectives, her participation in the accumulation of the collection which the Institute will house and her contributions to the planning of the project, make the new name wholly appropriate.”[20] In fact, after Sterling’s death in Williamstown following a challenging year that ensued from a stroke four months after Francine cut the ribbon at the Institute’s opening ceremony in May 1955, she served on the board until her death in 1960. Ganz might minimize her contribution as a board member as “looking to maintain her husband’s wishes”, an admirable goal as founders of institutions do sometimes struggle to maintain their intent. Francine appears to have been instrumental in the appointment of the Institute’s first curator, William Collins, whom she knew as a prints and drawings specialist through Knoedler’s in London and New York.

The presentation, re-presentation and at times mis-presentation of the history of the Clark collection raises important issues that scholars must consciously consider. What do those who write the histories of art collections have at stake in defining collecting through the scope of a masculine paradigm of capitalist commodification? The male figure within the heterosexual matrix of a collecting couple is, historically, typically the source of the financial means; there is, of course, considerable literature on the “exceptions” such as Gertrude Stein and Isabella Stewart Gardner. Why are historians unable to separate the traditionally gendered nature of finances, particularly inheritance, from the formation of taste and art collecting? There is no extant diary or other textual evidence from Francine, but Sterling’s written records are clear to non-gender biased eyes.

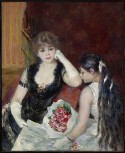

The collection itself is testimony to the couple’s exceptional skills as connoisseurs and the works are beautifully displayed in the installation at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (figs. 4, 5, 6, and 7). Renoir’s A Box at the Theater (At the Concert) (1880, acquired 1928, cat. 56, fig. 8), Jean-Léon Gérôme’s The Snake Charmer (ca. 1879, acquired 1942, cat.40, fig. 9), Camille Pissarro’s The River Oise near Pontoise (1873, acquired 1945, cat. 23, fig. 10), Cassatt’s Offering the Panal to the Bullfighter (1873, acquired 1947, cat. 29, fig. 11), Berthe Morisot’s The Bath (1885–85, acquired 1949, cat. 69, fig. 12), Monet’s Seascape (ca. 1866–67, acquired 1950, cat. 12, see fig. 4, far right), and Toulouse-Lautrec’s Waiting (ca. 1888, acquired 1952, cat. 71, fig. 13) are all strong, representative works and important pieces within the œuvre of each artist. Of the 73 works in the catalogue (74 works in the exhibition, which includes a cast of Edgar Degas’ Little Dancer Fourteen Years Old) 64 were acquired by the Clarks (fig. 6). The exhibition also includes two bequests and seven works purchased by the Institute, often in memory of a trustee or director, as was the case with Tissot’s compelling Chrysanthemums (ca. 1874–76, cat. 46), an excellent acquisition appropriately made in memory of David S. Brooke, director from 1977 to 1994 (fig. 14). As the exhibition moves ahead with its global itinerary, the compelling works will continue to attract crowds; one can only hope that the engaged and passionate collecting couple behind the Sterling AND Francine Clark art collection will not be lost to contemporary viewers.

Alison McQueen

McMaster University

ajmcq[at]mcmaster.ca

[1] Gabriel P. Weisberg, Decourcy E. McIntosh and Alison McQueen, Collecting in the Gilded Age: Art Patronage in Pittsburgh, 1890–1910 (Pittsburgh: Frick Art & Historical Center, 1997).

[2] The important scholar of collecting practices, Susan M. Pearce, examines this concept in her chapter “Engendering Collections,” in On Collecting: An Investigation into Collecting in the European Tradition (London: Routledge, 1995), 197–222.

[3] Nicholas Fox Weber, The Clarks of Cooperstown (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007), 150–51.

[4] James A. Ganz “From Paris to Williamstown: Robert Sterling’s Life as a Collector,” in Michael Conforti et al. The Clark Brothers Collect: Impressionist and Early Modern Paintings (Williamstown: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 2006), 35-121.

[5] Arjun Appadurai, The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986); Jean Baudrillard, “The System of Collecting,” in The Cultures of Collecting, eds. John Elsner and Roger Cardinal (London: Harvard University Press, 1994); Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library: a Talk about Book Collecting,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968); Susan M. Pearce, Collecting in Contemporary Practice (London: Sage, 1998); Michael Thompson, Rubbish Theory: The Creation and Destruction of Value (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979).

[6] Conforti et al., 38.

[7] Weber, 152. Abbreviated details cited by Ganz (2011), 5.

[8] Weber argues that Clark sought to release his inheritance from the trust that defines his shares as the property of his brothers and their children since he did not have his own children, except through marriage. The lawsuit was lost before the State Supreme Court in October 1927. Weber, 172.

[9] Michael Conforti “Preface” in David S. Broooke, Master Drawings: Sterling and Francine Clark as Collectors (Williamstown: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1995), 7.

[10] David S. Brooke, Master Drawings: Sterling and Francine Clark as Collectors (Williamstown: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1995), 10.

[11] Brooke, 9.

[12] Brooke, 12.

[13] Brooke, 12–13.

[14] Brooke, 14.

[15] Michael Conforti, “Preface” in Steven Kern et al., A Passion for Renoir: Sterling and Francine Clark Collect 1916–1951 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), 4.

[16] Steven Kern, “A Passion for Renoir” in A Passion for Renoir: Sterling and Francine Clark Collect 1916–1951 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), 11.

[17] Kern, 11.

[18] Kern, 100, endnote 18.

[19] RSC Diary 19 January 1924, as cited by Weber, 160, fn 54. See also RSC Diary 29 March 1926, as cited by Weber, 161.

[20] Conforti et al., 24. The Clark family had important connections with Williamstown as it was home of Williams College, from which Sterling’s grandfather Edward Clark graduated and where both his grandfather and father, Alfred Corning Clark, had served as trustees.