The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

The New Courbet Museum Opening and Exhibition: Courbet/Clésinger[1]

Pour peindre un pays, il faut le connaître. Moi je connais mon pays, je le peins. Ces sous-bois, c’est chez moi, cette rivière, c’est la Loue, celle-ci le Lison ; ces rochers, ce sont ceux d’Ornans et du Puits noir. Allez-y voir, et vous reconnaîtrez tous mes tableaux.[2]

-- Gustave Courbet

These have been good years for Gustave Courbet’s legacy. In both his native France and the United States, scholars continue to publish books, articles, and museum catalogues that examine the seminal master’s work. Surely his once underestimated role in the development of modern art has fully emerged. The great Courbet retrospective at the Grand Palais in 2007, organized by Laurence des Cars and Dominique de Font-Réaulx, was a splendid successor to Hélène Toussaint’s ground-breaking exhibition organized in 1977 at the same venue.[3] Both showed what careful planning, patience, and thorough knowledge can achieve since both will serve as landmarks in the artist’s hagiography. In the 2007 exhibition, the relationship of Courbet’s Realism to photography received significant attention, from his landscapes to his portraits and erotic nudes. Meanwhile, Petra Chu’s book on Courbet and the media, The Most Arrogant Man in France, showed more conclusively than ever how Courbet promoted himself and manipulated the press.[4] And another important exhibition organized in 2010 for Frankfurt, Klaus Herding’s Courbet: A Dream of Modern Art examined the painter’s more romantic side, complementing and complicating the artist’s still too often one-dimensional reputation as a Realist.[5] Recent articles and essays on topics such as Courbet’s hunts, his relationship to utopian philosophies, and his interest in music highlight such complexities even further.[6] A forthcoming conference “Transfers de Courbet,” organized by University of Paris psychiatrist Yves Safarti, will surely add its several cents worth with papers whose titles include “(Interpsychic) Scenes from the Lives of Courbet/Oudot” and “Signs of Periodic Insanity in the Life and Work of Courbet.”[7]

The time had thus long since come for the once tiny and antiquated Musée Gustave Courbet at the painter’s birthplace in the charming town of Ornans to receive a facelift that would put it on a par with other homesteads of celebrated artists whose houses and/or studios have been converted to museums (fig. 1). In many, such as the famous Musée Gustave Moreau in Paris, the artists’s studios have been endowed with huge collections. In others, like the Cézanne studio in Aix-en-Provence, little remains except for easels, props, and sundry equipment. The Courbet Museum, originally limited to the family home, has been expanded through the purchase of the two adjoining houses, to its right and to its left. Yet its setting is as authentic as Giverny’s gardens, and although far less spacious than Monet’s home and enclosures, it lends itself better to discovering the wider natural surroundings in the countryside that so inspired the artist. The gray cliffs characteristic of the Jura region and ubiquitous in Courbet’s landscapes can be seen from almost everywhere in the town, as well as from the museum’s new windows.

The original Musée Gustave Courbet was the hope of Courbet’s sister, Juliette, as early as 1903, and was eventually fulfilled thanks to the painter Robert Fernier, who authored the first catalogue raisonné of Courbet’s works. In 1938, Fernier founded the Friends of Gustave Courbet, whose goal was to turn the Courbet house, purchased by the Friends, into a museum. It first opened in 1971. In 1976, the Fernier group turned the museum and collection over to the administration of the Département of the Doubs, named for the river (pronounced “Dou …”) that runs through it. It continued to collect and support the museum. Sometime later, Claude Jeanneret, Socialist Party Senator from the Département and President of the Conseil général du Doubs, took up responsibility for expanding the museum as his pet project. After three years of construction, the original house (called the Hôtel Hébert) has been restored and the adjoining houses (Hôtels Champereux and Borel) have been renovated to international museum standards.[8] The original museum has thus quadrupled its surface area, to a respectable 2,000 square meters (approximately 2,400 square yards). For Jeanneret, this year’s opening was a victory not only for Courbet and the town, but also for the Doubs region, which has redefined itself as “Courbet Country.”

A few critics miss the architectural quaintness of the original narrow stairway entrance, which they feel has given way to a slick corporate look—a “Courbetland”—like the entrance to a boulevard movie house that is out of place in the neighborhood.[9] By contrast, others appreciate the safety, security, convenience, and airiness of the new entrance, with its full glass façade. Besides, facing the museum across the Place Robert Fernier is a relatively recent, modest, and utterly undistinguished apartment building that can only benefit from the new museum’s prestige. Even more daring for tradition in an ancient region like Franche-Comté is the glass enclosed passageway cantilevered over the Loue River that connects one house to the other at the rear (fig. 2). All three houses back up to the waterway and had perfunctory rear windows, like most of their neighbors. Exceptional were those homes with loggias from which residents might watch the quick-flowing current, hail boaters, or salute neighbors across the way. The museum’s glass galley-way follows the latter tradition (fig. 3), but the architects have gone much further by constructing a glass stairway and landing at the ground floor with the river a few feet underfoot that makes it seem as if one is stepping into the stony riverbed itself. Shortly after this “virtual bath,” the visitor will discover the door to an inviting little garden and a tiny café where one can refresh with a Coke—forgive me, I’m American—while perusing the surrounding weathered walls or watching the lively Loue (fig. 4). There is even a proper gift shop, although its book section could certainly be improved.

The renovation financing was a collaborative effort between the municipal and regional governments, which have sought not only to do justice to Courbet, but also to enhance the region’s attractiveness to tourists by posting directional signage and in many cases improving access to sites that Courbet painted. Four brand new foldout brochures, each with a different hiking trail, are published under the title Les sentiers de Courbet (fig. 5). At least the Courbet enthusiast can now find the Gour de Conches, even though now, as in Courbet’s time, it takes some rough climbing to get down to his actual point of view. The deafening waters pouring from the cave of the Source du Lison, on the other hand, are easily accessible from the road, and the grandiose Source de la Loue in nearby Ouhans, is a fully developed tourist attraction, with all security measures, even though it is hardly besieged by crowds (fig. 6). Pays de Courbet is the regional slogan, with glossy schedules of concurrent cultural events, including exhibitions of contemporary artists at the renovated Flagey Farm once owned by Courbet’s father, which opened during the Courbet exhibition of 2007. The present exhibition shows a fascinating Alsatian painter named Alfred Geiss (1901–73) whose brightly colored work seems like a cross between Balthus, Courbet, Ingres, and Hopper, with a wink to Degas (fig. 7). In Ornans, there are also philosophy workshops, concerts, and art games for children. The announcement for last April’s “Musical Salon,” an homage to the famous soprano Pauline Viardot (1821–1910), showed Courbet’s Self-Portrait at Sainte-Pélagie Prison.

As with much intergovernmental and private collaboration, the inauguration was an immense affair, with over two thousand people in attendance—fully half of the population of Ornans itself (fig. 8).[10] Parking was established at least a mile away with shuttle service; the speeches were endless, not the least an art history lecture by former Musée d’Art Moderne director Werner Spies, who was invited for reasons I was unable to determine as sort of an honorary scholarly éminence grise. Jean-François Longeot, Mayor of Ornans, and other local and regional politicians all had their say. Most interesting was the address by Monsieur Jeanneret, who explained the renovation’s history from municipal to regional to national project. The architect, Christine Edelkins, spoke informatively, explaining her design concepts and the constraints that she faced. Originally scheduled for the event was Frédéric Mitterand, the Minister of Culture, but he was traveling with the Prime Minister in Indonesia. The French National Museums were represented by their director, Marie-Dominique Labourdette, who has launched an ambitious program of renovation and restoration for provincial museums (76 different projects) as well as the construction of a Louvre branch museum in Lens, a high-speed train stop in the declining industrial region of Lorraine. However, local political figures and their staffs, augmented by two former national cabinet ministers, vastly outnumbered any other category of attendee. Only the wine and cheese were equally abundant.

A French inauguration is never complete without a true celebrity and a meal. The first was Princess Caroline Aga Kahn, whose son has loaned a landscape. The second was a special dinner for select persons held in two of the town’s excellent and charming restaurants. I was the only American art historian present, although others were invited. The appetizer was the biggest surprise, a shrimp pâté with the name Courbet in mayonnaise along its top (fig. 9). Among the evening’s party favors were four imprinted chocolate squares, one with the regional logo and one with a picture of Courbet’s Self-Portrait in Sainte-Pélagie Prison (fig. 10). Courbet himself could hardly have been more self-indulgent.

Over the years, local Courbet lovers have contributed both their knowledge and their legacies so that the Courbet Museum has built up a modest collection of paintings and drawings. That is more than one can say for the Cézanne studio, or even the Rembrandt House in Amsterdam. Each institution has its particular history and supporters, and on that score, the people of the Doubs region and Ornans have been blessed. The collection is augmented by permanent loans from the Institut Courbet and private donors. The Institut, founded in 1999 as the administrative vehicle for the Friends, was the creation of Jean-Jacques Fernier, a Parisian attorney, following the regional takeover of the museum. It is said a certain rivalry exists between the Institut and the museum’s qualified art historians, but I found no sign of it whatever. While the Musée had its collection exhibited at the famous Saline of Arc-en-Senans during the renovation, the Institut had its exhibition at the Fondation Bismark in Paris this past spring, closing in time for its loans to be shipped to the museum.[11] The rivalry rumor comes perhaps from accusations that the Institut has not sufficiently accounted for 308,000 Euros of public funds meant to support the museum project.[12] On the other hand, the museum has a full gallery dedicated to the paintings of its founder, Robert Fernier, whose works were certainly inspired by Courbet’s but could never be mistaken for them.

The museum’s collection as exhibited combines several remarkable works with others that are sometimes perplexing. One wonders on what basis two tiny views of Ornans are attributed to Courbet. Yet there are also the early Pirate Prisoner of the Dey of Algiers (1844), the gigantic Saint Nicolas (1847), the stunning Portrait of Grandfather Oudot (1847), among other portraits, and the Miroir d’Ornans (ca. 1872), with its reflections of houses in the Loue, as well as several other lovely landscapes. Finally, there is the already mentioned Self-Portrait in Sainte-Pélagie Prison (1872). The Institut Courbet has several paintings on permanent loan, among the most intriguing of which are two presumably early pictures The Tinker [Le Rétameur] and the modest Crossing the Stream, ca. 1841–44 (fig. 11). In the latter, a young man dressed as if from a troubadour romance is fording the waters with his princess-like damsel in his arms. It is certainly authentic, signed with Courbet’s initials in red, and related stylistically to other early Courbets. A drawing for it is in the collection as well. The subject is intriguing for its relationship to Courbet’s youthful images of lovers and its possible literary inspiration. There is also a portrait of a man identified as Francis Wey even though the same picture has been known as Jules Dupré for some years (fig. 12). I could not discover on what basis the identification with Wey was made.

Musée Gustave Courbet is one of the few places where one can see pictures by Courbet’s disciples on public view. Cherubino Pata (1827–99) and Marcel Ordinaire (1848–96) are perhaps best known for paintings said to have been signed by Courbet. There may have been an element of truth to the rumor, which was surely meant to discredit Courbet, who was imprisoned after the Commune and then retreated to Ornans and Switzerland, where he died. It is more likely, however, that his assistants aided in preparing pictures that Courbet finished and signed, desperate as he was to pay off the exorbitant fine imposed on him when released from prison. When they placed their own signatures on their canvases, the two disciples have their own style, quite distinguishable from Courbet by the trained eye.

Before opening on to renovated galleries the visitor’s circuit takes one through the restored but still recognizable rooms of the old Courbet house (fig. 13). Those rooms are still naturally dark, so the paintings are lit by professionally installed track lamps, which glare on the individual pictures—boutique lighting of sorts. In the middle of certain rooms are drawings, prints or letters, protected by removable cloth covers. In others there are personal objects, such as a worktable, loaned by Mme. Marlis Ladurée, with drawers that once contained Courbet’s tubes of paint (fig. 14). Some of the rooms are cramped, but other than the inauguration itself, this is not a museum likely to attract great crowds at one time. A friend who visited a few weeks after the opening reported that there were only four other people in the building, considerably less than the number of staff. I certainly hope the minimal attendance was due to inclement weather or the time of day. Moreover, I expect there will be innumerable school tours and tour buses coming through. That, too, will be a problem, if the itinerary through the special exhibition galleries remains as confusing as it is currently, moving up and down stairs right in the center of the house in which they are located.

As one exits the original Courbet home into architecturally new territory, there is a see-through display of fascinating and important original documents (fig. 15). Following the circuit, and descending the staircase along which they are encased, I was torn between finding the concept gimmicky, with its annoying white twig-like rods, not especially original, yet successful as a change from the more claustrophobic house (fig. 16). Since one can view them from both sides, different documents in the display attract attention the second time around. Following the first look at the display, the only way out is through a room in which a mediocre video explains A Burial at Ornans, with more than one mistake and little use of the more enlightening art historical interpretations. The same can be said of the guides, whose training could use improvement. Neither as of yet live up to the quality of the museum in which they present or are presented, nor, by a long shot, to the artist himself. The use of interpretive films has become a convention in modern museums, but others have seen fit to interview important scholars on different points of view, feature new discoveries, or somehow otherwise extend the viewer’s experience. A Burial at Ornans, exhibited in Paris, far from Ornans, is still quite distant even after viewing the film.

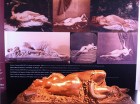

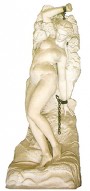

The inaugural exhibition Courbet/Clésinger: Oeuvres croisées [intersecting works] juxtaposes certain works by Courbet to a number of sculptures and paintings by his contemporary from nearby Besançon, Jean-Baptiste Clésinger (1814–83). It is worth noting that Courbet tried his hand at sculpture from time to time, as is more evident thanks to the Musée Courbet than any other collection of his work. Selected by the museum’s director, Mme. Frédérique Thomas-Maurin, who wrote her doctoral thesis on Clésinger, many of the comparisons are remarkable. For example, Clésinger’s best-known erotic work, Woman Bitten by a Serpent (1847, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), originally meant to be titled Dream of Love, finds analogues in Courbet’s Bacchante (ca. 1844–49, Musée Arp, Remegen, Fondation Rau), Reclining Nude (1866, Musée Mesdag, The Hague), and the more famous Woman with Parrot (1866, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Although Courbet and Clésinger knew each other, the question of influence gives way to an exploration of similar visions of the nude (fig. 17). Only the erotic boldness and the illusion of real physical presence, or in Clésinger’s case, its three-dimensional reality itself, single them out from among other images of the reclining nude, including their proliferation in photography. Another intriguing parallel is between Clésinger’s marble Andromeda (1869) (fig. 18) and Courbet’s painting, Trois Baigneuses (ca. 1865–68, Musée du Petit-Palais, Paris.) Ingres’ La Source might have been in both their minds. In addition, there are portrait comparisons, some of which are astounding in their resemblance. For example, Courbet’s Portrait of a Young Woman (1867, Collection Matsukata, National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo) and Clésinger’s bronze bust Lady with Roses (1867, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) is cause for a double take (fig. 19). Both artists portrayed the Duchess of Castiglione Colonna, a sculptor in her own right who went by the masculine name Marcello.

Madame Thomas-Morin and her assistant Julie Delmas have also assembled a remarkable group of essays for their catalogue. Among the more interesting ones, in addition to their introductions, are those by Anne Pingeot, who participated importantly in the exhibition’s organization and who places Clésinger in the sculptural context of his time; and Nicole Myers, an American art historian, whose quasi-parallel essay to Pingeot’s places Courbet’s nudes in the context of their time. Thierry Savatier concentrates on portrayals of his near-namesake, Apollonie Sabatier, and Thomas Schlesser compares Courbet’s and Clésinger’s visions of landscape. Indeed, it was fascinating to discover Clésinger’s landscapes (fig. 20), which prove the extent to which this very different genre can cause a divergence in both style and concept even when painters share their vision of the nude.

If there were a lesson to be learned from both the inauguration and the renovation, it would be both social and museological. It is clear that the public and political support of a community are as important to a project as are a museum’s visionary donors, art historians, and architectural professionals. The Musée Gustave Courbet, once a curiosity of interest primarily to specialists in nineteenth-century art history, is now worthy of a visit by even the least initiated tourist, especially when one adds its affiliated geographic sites.

James H. Rubin

Professor of Art History, Stony Brook, State University of New York

jrubin[at]ms.cc.sunysb.edu

[1] This essay is dedicated to Marlis and Denise.

[2] “In order to paint the countryside, one must know it. Me, I know my country [and] I paint it. This undergrowth is on my land; this river, the Loue, is that of Lison; these rocks are those of Ornans and [the valley of] Puits Noir. Go see them and you will recognize them from my paintings.”

[3] Hélène Toussaint, et al., Gustave Courbet: 1819–1877, exh. cat. (Paris: Grand Palais, 1977); Laurence des Cars and Dominique de Font-Réaulx, Gustave Courbet, exh. cat. (Paris, Grand Palais, 2007).

[4] Petra T. Chu, The Most Arrogant Man in France: Gustave Courbet and the Nineteenth-Century Media Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007).

[5] Klaus Herding, Courbet: A Dream of Modern Art, exh. cat. (Frankfurt: Schirn Kunsthalle, 2010).

[6]Courbet à Neuf, Actes du Colloque Courbet (December, 2007), Mathilde Arnoux, Dominique de Font-Réaulx, Laurence des Cars, eds. (Paris: Musée d’Orsay and Maison des sciences de l'homme, 2010); Courbet Revisited, College Art Association Session organized by Mary Morton and Karen J. Leader, Los Angeles, February 30, 2009; Noël Barbe and Hervé Touboul, eds., Courbet/Proudhon, l’art et le people, exh. cat. (Besançon: Saline Royal d’Arc-en-Senans and Les Editions du Sekoya, 2010); Noël Barbe and Hervé Touboul, Courbet, peinture et politique, Actes du Colloque de l’Université de Franche-Comté à la Saline Royale d’Arc-en-Senans, September 17–19, 2009, publication forthcoming.

[7] Kursaal, Besançon, September 8–9, 2011.

[8] For a French video link, narrated by Julie Delmas, Assistant to the Curator of the museum, go to:

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xkfhhc_exposition-courbet-clesinger-musee-courbet-a-ornans-jusqu-au-3-octobre-2011_creation

[9]http://www.lefigaro.fr/culture/2011/06/24/03004-20110624ARTFIG00431-polemique-autour-de-la-maison-de-courbet.php

[10] A slide show of the event can be found at http://www.macommune.info/actualite/diaporama-claude-jeannerot-courbet-est-de-retour-dans-sa-ville--21147.html.

[11]Gustave Courbet: L’amour de la nature, exh. cat. (Paris: Fondation Mona Bismark, 2011).

[12]L’Est républicain, July 2, 2010, n.p.