The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Makart: Painter of the Senses

Belvedere, Vienna

June 9 – October 9, 2011

Catalogue

Makart: Painter of the Senses (Makart: Maler der Sinne).

Agnes Husslein-Arco and Alexander Klee, eds. Preface by Husslein-Arco; essays by Marvin Altner, Stephanie Auer, Rainald Franz, Werner Hofmann, Klee, Katharina Lovecky, Uwe Schlögl, Martina Sitt, Werner Telesko, Markéta Theinhardt, Thomas Wiercinski.

Munich and London: Prestel, 2011.

252 pp.; 175 color illustrations, 15 b/w; chronology, bibliography, list of exhibited works; list of works by Makart in the Belvedere.

ISBN: 978-3-7913-5151-3 (English trade edition)

978-3-7913-5150-6 (German trade edition)

€39,95 ($49.95; £35)

Makart: Ein Künstler regiert die Stadt

Wien Museum in the Künstlerhaus

June 9 – October 16, 2011

Catalogue

Makart: Ein Künstler regiert die Stadt.

Ralph Gleis, ed. Foreword by Wolfgang Kos, introduction by Ralph Gleis; essays by Kurt Bauer, Elke Doppler, Gleis, Werner Kitlitschka, Kos, Doris H. Lehmann, Michaela Lindinger, Eva-Maria Orosz, Hans Ottomayer, Alexandra Steiner-Strauss, Werner Telesko.

276 pp.; 320 color illustrations, 3 b/w; chronology of Makart and his period, numbered brief entries for exhibited works, list of references.

ISBN: 978-3-7913-5152-0 (German trade edition)

€39,95 ($49.95; £35)

An unusual cooperative undertaking in 2011 by two Viennese museums opened grandiose new perspectives on the Austrian painter Hans Makart (1840–1884). Simultaneous exhibitions approached his entire body of work from different points of view. The Belvedere, which includes forty-four works by Makart in its own collections, focused on his exuberant use of color and his "sensational painting" in their show titled Makart: Painter of the Senses (fig. 1). The Wien Museum, also with important and varied holdings of the artist and his contemporaries, illuminated the phenomenon Makart and his impact on Viennese society in its exhibition Makart: An Artist Rules the City (fig. 2).

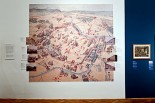

The Wien Museum show took place in the Künstlerhaus, its façade behind a scaffold flaunting a banner in Makartian proportions (fig. 3). Both an artists' society—celebrating its sesquicentennial in 2011—and an exhibition space, the Künstlerhaus had launched Makart's greatest successes. There in the autumn of 1868, for the first exhibition held in the society's new building, the painter sent from Munich his triptych Modern Cupids (1868; Bank Austria Kunstsammlung, Vienna) and displayed with them a sketch (now in the Belvedere) showing how the pictures could be installed in an interior. Count Johann Palffy bought the three paintings from the show and commissioned further room decorations from the artist. A few months later the Salzburg native Makart accepted a summons from Emperor Franz Joseph I and moved from Munich to Vienna.

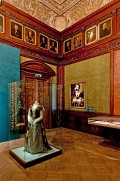

The Belvedere decided to forego banners and to plaster the city's many poster columns with a detail of Bacchus and Ariadne (1873–74), the design for a curtain at the Komische Oper and one of two Makart behemoths in their collection (fig. 4). The museum offered, in addition, a tantalizing prequel to the show. Bacchus and Ariadne, retrieved from storage, returned to the gallery of the Upper Belvedere where it had hung until November 2009 (figs. 5–6). There visitors in January 2011 could observe conservation procedures to prepare the picture for the summer exhibition at the Lower Belvedere.[1]

After so much publicity, the triumphant Ariadne might have been expected to lead the way to the Makart show inside the museum.[2] Instead, the entry panel bore floor-to-ceiling wallpaper printed in blood-orange and brown tones with the exhibition title superimposed on a huge, unidentified image. Surprisingly, the wallpaper reproduced a detail from a picture too big to travel to Vienna: The Entry of Charles V into Antwerp. That monumental canvas had been seen by some 30,000 viewers at the Künstlerhaus in 1878 before winning a medal of honor at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. It was then exhibited in nine other European cities until its purchase in 1881 by the Kunsthalle in Hamburg, where it remains the largest work in the collection. As a substitute, the Hamburg museum lent its dazzling preparatory study for the picture, hung in the first room of the exhibition next to a larger study from the Belvedere (fig. 7).[3]

On one long wall of the initial gallery hung the three paintings of Makart's Modern Cupids triptych (1868; Bank Austria Sammlung, Vienna), on the other the resplendent Venice Pays Homage to Catherine Cornaro (fig. 8). The painting of the Cypriot queen had first been shown to a vast public at the Künstlerhaus; Makart's dealers H. O. Miethke and Karl Wawra had rented the galleries for a special exhibition during Vienna's World Exposition in 1873. Shadowing its success was the death in June 1873 of the model for the queen, Makart's wife Amalie. For the Belvedere show, the thirty-five-foot painting was surrounded by violet velvet masking the entire wall; overhead dangled the section title—"Sensation"—in puffy Makart-red velvet letters, an intervention commissioned from the artist Gudrun Kampl. No such drapery was deemed necessary in 1876 at Philadelphia's Centennial Exhibition when the picture was the focus of the Austrian section at Memorial Hall, or around the frame at the Nationalgalerie in Berlin where it hung on the stairway from 1877 until 1933.[4] Hitler bought Catherine Cornaro for his planned museum in Linz in October 1940, after Berlin had lent the picture that summer to the Makart centennial exhibition in Salzburg (53).[5]

Velvet pleats and suspended letters at the Belvedere suggested an ironic approach to Makart. By contrast, for the last large retrospective forty years ago—during a decade when serious study of the neglected nineteenth century began to flourish—Klaus Gallwitz, director of the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, unabashedly installed the paintings on the bare white walls of his Jugendstil building; he decided to let the works speak to a new public in Makart's own sensual language.[6] In the Belvedere show the velvet masking worked better in the darkened second room, where it included the rear walls of the two alcoves (fig. 9). Spotlights illuminated Makart's five nude allegories of the senses, Auguste Renoir's After the Bath (1876; Belvedere), and the imitation architecture of the baroque ceiling of the palace. The plush letters spelling "Senses," strung vertically, were unobtrusive as a parallel to the Makart nudes.

An apt comparison in one alcove displayed a small version of Thomas Couture's Romans of the Decadence (1847; Musée d'Orsay, Paris) with eight of Makart's pencil drawings (Münchner Stadtmuseum) for another triptych: The Plague in Florence (1868; Georg Schäfer Sammlung, Schweinfurt). The finished paintings were shown at the second exhibition in the Künstlerhaus in December 1868 and purchased in January 1869 by an art dealer. In Paris, the French director of fine arts Emilien de Nieuwerkerke allegedly found the orgiastic trio too shocking for the Salon. The Austrian press, which had just announced that Makart had agreed to settle in Vienna, reacted with surprise, reporting that Nieuwerkerke—under diplomatic pressure—had explained the Salon rule: only two paintings per artist could be exhibited, not three. Makart insisted on showing all three or none, and the official "rejection" guaranteed the young artist an early international success (41).[7] The second alcove explored further Makart and France, indicating the influence of Delacroix through a small replica of the Louvre's Galerie d'Apollon ceiling (1851) to suggest inspiration for Makart's uncompleted project for the stairwell ceiling at Vienna's Kunsthistorisches Museum (1883–84). Delacroix's Barque of Dante was economically represented as well, through an early copy by Anselm Feuerbach (1851–52; Bona Terra Foundation, Geneva). The alcoves each contained a fascinating interpretation of Dante and Virgil by Makart from about 1863–64; the larger study from a Czech private collection revealed his careful study of the Barberini Faun (Glyptothek, Munich) during his Munich period and his impulse to score paint with the end of his brush (11, 148–9).

The third room—"Friends"—hinted at the enduring influence of Makart's training at the Munich Academy. The painter's handsome portrait of Bertha von Piloty hung near a single stunning composition by her husband, his teacher Carl Theodor von Piloty (figs. 10–11). Makart had clearly absorbed dramaturgy from the painter of this adaptation of a scene from Shakespeare's Henry VIII. The fourth room, "Myth," displayed Bacchus and Ariadne in the context of analogous subjects (fig. 12). Among them was Makart's sparkling oil-on-wood sketch for Hunting Party of Diana (1879; private collection), one of several small versions of a colossal painting purchased from the artist in 1880 by James H. Banker, a New York financier, and given by his widow to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1888. The museum de-accessioned the large Diana in 1929, and John Ringling acquired the painting at auction for his new museum in Sarasota, Florida.[8] Hanging opposite Makart's Ariadne in the timeless milieu of myth at the Belvedere, Feuerbach's Orpheus and Eurydice (1869; Belvedere) seemed wonderfully appropriate; Adolf Hirémy-Hirschl's newly-dead souls on the banks of the Acheron (not in catalogue) was an inspired choice and a welcome surprise, despite its late date and Secessionist frame (fig. 13). A short chronology and a portrait of Makart by Franz von Lenbach, his friend and fellow painter-prince from Munich, faced an enlarged photographic portrait in the narrow fifth room.

Two puzzling late architectural fantasies (1883) were shown in the sixth room, works possibly related to the building of the Kunsthistorisches Museum by Gottfried Semper and Karl von Hasenauer. There were also two paintings on Wagnerian subjects: Design for a Ceiling Painting with Motifs from the Ring (c. 1870–72; Belvedere) and The Sinking of the Nibelung Treasure in the Rhine (c. 1882–83; private collection).[9] The early Hagen Strikes Siegfried (1866–68; Bank Austria Kunstsammlung, Vienna) was taken by Makart directly from the Nibelungenlied. The remaining half of the sixth room was a bare-bones reconstruction of the Makart Room in the Ringstraße house of the patron of the arts Nicolaus Dumba, the only complete room designed by the artist. His ceiling – Four Allegories of Music – was a tribute to Dumba as a supporter of the Musikverein; it was acquired by the Chi Mei Museum in Taiwan after the auction of expropriated Jewish property held in October 1996 by Christie's at MAK, the Österreichische Museum für angewandte Kunst (168).[10] The wall paintings were installed for the Belvedere exhibition in a rough approximation of the original arrangement, with a large photographic reproduction mounted overhead as a stand-in for the ceiling (fig. 14). In the seventh and final room were further works related to Nicolaus Dumba and two studies for the lunettes of the stairwell of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, as well as a small section of photographic portraits. With his large Death of Cleopatra in Kassel still on tour in Orientalisme en Europe, Makart's trip to Egypt with artist colleagues in 1875–76 was evoked by An Egyptian Princess (Sammlung Humer Privatstiftung); the Egyptian sojourn of Makart, Lenbach, Leopold Müller and their group would make an interesting show in itself. A final gift as the taillight of the show was the lovely Lady in a Feather Hat, Seen from the Back (1874–75; Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg).

Some of the ten Belvedere catalogue essay titles end with a question mark – a sign of active inquiry. The elegant lead essay is "Makart: A Pioneer?" by Werner Hofmann. The Vienna-born art historian mentioned and illustrated the painter in his book of 1960 – The Earthly Paradise – and hauled the Entry of Charles V into Antwerp out of storage when he became director of the Hamburger Kunsthalle in 1969. Hofmann impressively describes the critical mass of history painting during the Vienna World Exposition of 1873 (11–15). Makart's Catherine Cornaro was on view at the Künstlerhaus, while at the Kunstverein in the inner city Wilhelm von Kaulbach, director of the Munich Academy, was showing Nero during the Persecution of the Christians, with Gustave Courbet's The Artist's Studio (1855; Musée d'Orsay) and other works under the same roof. Piloty's Thusnelda in the Triumph Procession of Germanicus (1869–73; Neue Pinakothek, Munich) was the main painting in the art exhibition on the fairgrounds in the Prater, where the art lover could also see The Fall of the Rebel Angels (1841; Musée Wiertz, Brussels) by Antoine Wiertz and Feuerbach's Iphigenia (1871; Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart). Feuerbach, who had arrived in Vienna on May 19 to take up his appointment as professor of history painting at the Academy, had to wait to show his Symposium of Plato (1871–74; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie) until Makart removed Catharine Cornaro from the long wall at the Künstlerhaus.[11]

In his magisterial essay on Makart as pioneer, Hofmann refers to the core of pageantry in the artist's practice, and his anticipation of sequential photography in The Five Senses. Werner Telesko also explores in an essay on history as "poetic invention" how Makart assembled compositions "from a succession of individual motifs" and his role in undermining the hierarchy of genres (45). Markéta Theinhardt's study of Makart's reception by French critics ("Are You a Makartist or an Anti-Makartist?") is particularly interesting, as is curator Alexander Klee's look at Austrian responses to Makart: those of Ernst Wilhelm von Brücke, a physiologist, and Ludwig Hevesi, the critic who wrote the inscription for the Secession building – "To every age its art, to every art its freedom." All the catalogue essays are of top quality and beautifully illustrated, but without an index or individual entries, using the book is strenuous.[12]

An intrepid fan could walk directly from the Belvedere past the Karlskirche to the Künstlerhaus and climb the marble stairway to the very room where the artist first exhibited in Vienna (fig. 15). A pair of Makart bouquets proclaimed the Makart era upstairs. As explained by curator Ralph Gleis in extracts from his catalogue introduction used as a wall text outside the first room, it was a period in which the painter influenced "not only art, but contemporary taste in theatre, interior design, and fashion." Makart: An Artist Rules the City began with his studio, which he had insisted the emperor make available – at state expense – when he arrived in Vienna with his bride, Amalie, in 1869. The artist proceeded to arrange the studio space "as a stage in which he could flaunt his social status and cultivate his image." Makart had, the text continued, a "remarkably modern approach, not only to painting but also in his strategies for image building and the marketing of his art." The comparison is often made with Andy Warhol and his Factory.[13]

Inside its original wooden doors, the main gallery at the Künstlerhaus was screened by a digital print on satined adhesive film of a watercolor by Rudolf von Alt, showing the studio as it was in March 1885, just before the auction of the Makart estate (fig. 16). Beyond the screen was a charming synecdoche of the studio. The centerpiece, as in 1885, was the artist's last painting, Spring (1883–84; Salzburg Museum), intended as part of a cycle of seasons and hanging in the show on a Makart-red wall (fig. 17). The central model for Spring was the artist's second wife, Berta Linda, a former prima ballerina at the Hofoper, whom Makart had married to general disapproval in the summer of 1882. On an easel to the left was a portrait of his first wife; in the watercolor inspiring the installation, the Amalie Makart portrait was on the floor, leaning against the frame of Spring. To the right of the large painting was Hanna Klinkosch (before 1884; Wien Museum), the daughter of a well-known silversmith and purveyor to the court; her portrait had appeared unframed in the lower right of the watercolor (85). An assembly of photographs of the Makart studio on the Gußhausstraße, as well as more than a dozen reproductions of documentary photographs of other artists' studios from the period, were mounted behind the partition holding Spring. The material selected for the "Studio" section convincingly suggested the texture of the life of a painter-prince and revealed the extent to which Makart surrounded himself with real still-lifes as an extension of his painting.

Oddly, only four Makart self-portraits are known, and three of them were in the show, aligned over his many histrionic photographic portraits in a corner of the initial room devoted to "The artist and his image." A self-portrait from the Salzburg Museum, dated about 1869 by Elke Doppler in her catalogue essay, shows Makart in Renaissance costume with a dark red velvet beret. It was perhaps painted in Munich, Doppler speculates, in connection with the future painter-prince's summons to Vienna (45 and n.13).[14] Albumen prints of Makart by Franz Hanfstaengl in Munich and Josef Löwy, Victor Angerer, Adèle, and others in Vienna demonstrate not only the artist's discriminating choice of leading photographers, but his concerns for costume and pose in images that could have a far wider distribution than a painted portrait. Doppler points out an effort to allay gossip through his only known family photograph with his second wife, Berta, and his two children by his first wife (48). Next to the photographs stood a lively terracotta portrait bust by the French sculptor Gustave Deloye, who stimulated a neo-Rococo revival during his years in Vienna through his influence on Viktor Tilgner (fig. 18).

The section on the studio ended with a wall of brilliant portraits of contemporary painters, none of them by Makart but giving faces to the professional arena in which he competed. Hans Canon had returned to Vienna in 1873 and worked chiefly as a portraitist. In the last year of his life, Canon completed the stairwell ceiling and lunettes of the Naturhistorisches Museum (1885), having received the twin contract to that given to Makart in 1882 for the Kunsthistorisches Museum. After Makart died in 1884 leaving only the lunettes and the study for the ceiling now in the Belvedere, Canon inherited Makart's commission as well. He himself died in September 1885, and the art museum ceiling was finally assigned in 1887 to Mihály Munkácsy. Both Canon and Munkácsy were present in the show with portraits from the Wien Museum by Hans Temple. Jan Matejko (National Museum, Kraków), whose portrait in the exhibition was by Izydor Jablonski, was one of the "three great M's," as the critic Hevesi referred to Makart, Munkácsy, and Matejko. A Self-Portrait by Feuerbach (1878; Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum Hannover) hung near a vitrine with the first page of a manuscript of his polemic "Concerning Makartism, Pathological Appearance of Modern Times," written in 1873, the German artist's first year in Vienna. On the wall above his image were his peevish words from the tract: "This diarrhea-like production in his Asiatic junk shop displeases me and will go out of fashion."[15]

When Feuerbach died suddenly in Venice in January 1880, Makart held the professor's chair at the Vienna Academy that his disgruntled predecessor had vacated in 1876. Far from going out of fashion, Makart was at the peak of his career, a triumph achieved through ceaseless work and "Calculated Scandal" – the section title of the second room. Doris H. Lehmann's catalogue essay attributes his success to many factors: courageous decisions, a large measure of flexibility, and a keen sense of the evolving art market, among others (50).[16] The viewer could examine in this section, for example, Makart's combined painting and photograph (1868; Kunstmuseum St. Gallen) with the three parts of the earliest touring "sensation" – The Plague in Florence – set in a loggia with a Madonna on top of the central frame, as much a dream exercise as his late architectural fantasies displayed in the next section (179). A preliminary study for The Entry of Charles V into Antwerp reveals photographic layovers to aid recalibration of the composition; below the painting was a vitrine with a sample of photographic details of the Entry offered for sale after 1878 and the etched reproduction by Adolphe Lalauze first published in L'Art (1879).

The third section, "The Ringstraße as an Opportunity for Experimentation," brought together surviving examples of Makart's decorations for private patrons (fig. 19). Overhead was a living room ceiling – The Four Times of Day – painted in 1872 for Anton Oelzelt Ritter von Newin, who had made a fortune in the building trade. Sold and resold after the death of Makart's patron in 1875, the canvases were recently re-discovered in the Hofmobiliendepot. A beautiful study for the Dumba Room ceiling (1870–71; Landesmuseum Niederösterreich, St. Pölten) revealed a central baldacchino, replaced in the final version now in Taiwan by four putti ascending on a globe (182). Makart's contemporaries were also assigned a wall in the Ringstraße room. Three of Feuerbach's plans from 1874 for the ceiling of the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts aula, not yet installed when the painter resigned and left Vienna two years later, could be compared with later studies by Canon and Munkácsy for their museum ceiling projects (68–9). Without seeing the new art museum building, Munkácsy executed a wonderful artists' pantheon in Apotheosis of the Renaissance; after appearing in the Paris Salon in May 1890 as Allegory of the Renaissance, the ceiling arrived unaccompanied in Vienna that August.

Surprisingly, the art museum was Makart's first state commission. When he died, Makart had all but completed his twelve lunettes for the Kunsthistorisches Museum depicting ten painters with their models and two allegories. His Titian lunette at the museum had an echo, shown in the first room at the Künstlerhaus: Homage of the Artist to Female Beauty (1884; private collection), part of a ceiling decoration for his own salon. In this last self-portrait, Makart had joined the artistic nobility in the costume of a Renaissance painter-prince, complete with sword. Reversing the lunette composition, Makart silhouetted himself against the arch of the fictive architecture as a young Titian painting a Venus; the model was his second wife in the Messalina or Catherine Cornaro pose. At the end of the third room of the exhibition, a segment documenting various painting commissions along the Ringstraße, hung a study by Makart for the lunettes of Murillo, Velásquez, and Leonardo (1881; Belvedere).

In a catalogue essay on social and political change in the Makart era, Kurt Bauer called the crash of the Vienna stock exchange on May 9, 1873 (Black Friday) – only days after the World Exposition opened – "the mother of all world economic crises" (35). Both the state and Makart's wealthy patrons had to tighten their belts, and a number of ambitious projects were abandoned. An interesting map of Vienna in the third room pointed out the palaces of Makart's clients, with photographs of the exteriors of buildings for which he decorated walls and ceilings (fig. 20).[17] The fourth room, "Painted Music," was a Wagnerian interlude with musical excerpts from Rheingold and Die Walküre accompanying powerful scenes from those operas from the National Gallery in Riga, shown in Vienna for the first time since Makart painted them in 1883. Next came an impressive period room, "Living in Makart Style: Bombast and Opulence." The décor of the fifth room was a pastiche of exotic ingredients – dried palm leaf and reed bouquets, a polar bear skin, a painted ostrich egg – and included Anton Romako's The Salon of the Römer Family (fig. 21).

A few steps away the visitor entered the sixth room presenting Makart as a painter of women and society portraitist. Central in this gallery of beauties and their gowns were Hanna Klinkosch (1875) in a standing portrait lent by the Collections of the Prince von und zu Liechtenstein (she married into the family in 1890) and Dora Fournier-Gabillon (c. 1879; Wien Museum), the daughter of prominent Hofburgtheater actors Zerline and Ludwig Gabillon and later the wife of the historian August Fournier (fig. 22). That Makart's marriage proposal to Dora Gabillon had been refused, the catalogue suggests, may account for the retouched but evident scratch marks on the face of her portrait (211). A velvet Venetian fan with ivory handle made by Makart's mother as a studio prop – similar to the one Dora holds – was displayed in a vitrine. The spicy catalogue essay by Michaela Lindinger brings the portraits to life, without neglecting an analysis of Makart's astonishing impasto painting of the women's clothes, contrasted with the silken surface of their skins; he often painted the portraits on wood. The curator ingeniously installed the women in the Künstlerhaus founders' room below its frieze of all-male portraits; among the bearded worthies, he spotlighted one by Makart: Count Edmund Zichy, painted in 1872 (fig. 23).

"A Flood of Color on the Stage: Pathos and Passion" was dramatized through choice objects in the seventh room. Like his teacher Piloty, Makart painted Shakespearean subjects. On view in the Ringstraße section, viewers had seen his use of Midsummer Night's Dream in a design for the Empress Elisabeth's bedroom at the Hermes Villa in the imperial hunting grounds; in the section devoted to the stage was an elaborate theatre curtain on the same theme painted ten years earlier (fig. 24). Makart's friend, the German tragedienne Charlotte Wolter, dominated the room in her role as Messalina, reclining in a painted splendor of fabric and roses, her classical profile turned to watch Rome burn (fig. 25).[18] In the dimly-lit gallery, a screen console with earphones drew visitors to a scene in the Willy Forst film Operette (1940), with the female lead posing in Makart's studio as a mirror image of Wolter as Messalina.

The illumination of the show, its rhythm of light and darkness that felt like a walk through a stage-set Venice, enhanced the satisfying installation of the material. A memorable phrase in Werner Hofmann's 1960 book described the Ringstraße as a Makart procession of building styles. Under blazing lights in the exhibition's colorful eighth and next-to-last room, the Makart procession honoring the silver anniversary of the imperial couple, held on April 27, 1879, seemed to roll before the visitor's eyes down the length of the gallery (fig. 26). In addition to documentary photographs and artifacts from the spectacle, the Wien Museum collections include thirty-five oil sketches for parade floats by Makart, each nearly ten feet long; many were exhibited in city hall in late February 1879, arousing interest long before the municipally-sponsored anniversary event took place in April. Werner Telesko analyzes in his essay Makart's role in designing the procession, animating and costuming a cast of thousands; he also describes the souvenir publications using the latest photomechanical reproductive techniques. Significantly, as Telesko mentions, the anniversary celebrations marked the first illumination of the main Viennese monuments with electric light (110).

The ninth room – "The Death of a Legend" – was somber, but not lugubrious. One vitrine displayed the death mask; another held photographs of the funeral cortège passing the Künstlerhaus on the way to the cemetery, Makart's impressive final procession. Nearby was the Rudolf von Alt watercolor of his studio, seen as a reproduction on the screen at the beginning of the show. A plaster bust by Viktor Tilgner in that last room stood cunningly placed back-to-back with Deloye's terracotta in the first room, bringing the exhibition to a full circle (fig. 27). Tilgner had shown his bust at the Künstlerhaus in January 1885, only three months after Makart died of the side effects of syphilis on October 3, 1884. He was the obvious choice to produce a worthy public monument, and Tilgner relied on a photograph showing Makart costumed as Rubens for the 1879 procession, his enormous triumph on the Ringstraße (fig. 28). The sculptor also borrowed elements of the pose and costume from the Rubens Monument (1843) in Antwerp by Willem Geefs; Tilgner had used it for his own Rubens statue in stone for the Künstlerhaus (1879– 82). Makart had seen the Antwerp statue in 1877 as the official Künstlerhaus delegate to the festivities celebrating the tricentennial of the Flemish painter's birth. After Tilgner's death in 1896, plans were made to erect the late sculptor's statue of Makart in the Stadtpark, and the meeting took place in the Dumba Room (fig. 29). A painting by Hans Temple documents Nicolaus Dumba's near caress of the plaster model as Vienna's leading sculptors look on, under the Makart wall decorations with allegories of the sciences, sculpture, and painting seen in the Belvedere show (fig. 30). On the way out, the exhibition visitor could hear in a corner booth the voice of Willy Forst singing the nostalgic hit from about 1946, "Ja, das war die Makartzeit."[19]

The Wien Museum curator and his team deserve praise for a clear and entertaining narrative and installation at the Künstlerhaus. The catalogue and eleven essays are also of exceptional interest. Although the book lacks an index, it does have entries and cross-referenced page numbers for objects reproduced in the essays, making it a record of the exhibition that can be consulted with pleasure. The two Makart shows in 2011 gave Vienna and its visitors a binocular look at an artist central to the city's cultural past, and an essential figure in the history of taste.

From the beginning, Makart paintings have both fascinated and polarized viewers. Feuerbach was appalled at Makartism, yet his contemporary Adolphe Monticelli painted a copy of The Entry of Charles V into Antwerp (c. 1880; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon). Both Adolph von Menzel and Gustav Klimt esteemed his work. Makart would probably have preferred criticism to oblivion. Yet even before Black Tuesday in October 1929, his stock had tumbled in New York City. In early February that year the Metropolitan Museum of Art had included The Hunting Party of Diana among surplus works put up for auction. At about same time in the 1920s, however, the great Japanese collector Kojiro Matsukata, friend and patron of Claude Monet and Auguste Rodin, acquired Makart's The Love Letter to add to his holdings of French art. Sold at Christie's in 2010 and now in a private collection, the Matsukata Makart hung near Catherine Cornaro at the Belvedere in the summer of 2011 (157). Earlier last year a society portrait by Makart in a show at the Neue Galerie on Fifth Avenue had provoked the New York Times critic Roberta Smith to mock it as a "froth of cloying brushwork and sartorial detail." A few months later in Vienna, that same standing portrait of Hanna Klinkosch merited a place of honor among the women's portraits at the Künstlerhaus.

The critic Hevesi wrote a stirring tribute to the painter in June 1900 – Makart would have been sixty years old, and the writer himself was sixty. If Makart were alive, Hevesi wrote, he would be head of some Secession or other:

This little visionary had his day of omnipotence, in which he forced the world to see things as he saw them . . . . The German philistine's wife wore Makart's colors and dresses, every room in central Europe wanted to look a tiny bit like Makart's studio, every gathering of people wanted to be a gala procession. It is not an exaggeration to say: Makart was the most suggestive painter our German century has seen. Only he made an epoch, a "Makartzeit."[20]

Jane Van Nimmen

Independent scholar, Vienna, Austria

vannimmen[at]aon.at

[1] The conservation staff needed a vast air-conditioned space for their intervention and thought the picture's normal gallery would be ideal, even though the painting would have to be re-rolled and transported to the Lower Belvedere for the show. (For a video interview with the chief conservator, visit http://www.w24.at/, then enter “Bettina Urban” in search box “Suche.”) The museum had intended to follow the same procedure for their other mammoth Makart, Venice Pays Homage to Catherine Cornaro (1872–73). Hanging recently at the Wien Museum's Hermes Villa in the Lainzer Tiergarten, Catherine Cornaro – some nine feet longer than Bacchus and Ariadne – proved to be too large for treatment at the Belvedere and had to be prepared for the show off-site.

[2] To ease circulation in the Lower Belvedere, the public cannot be encouraged to linger in the narrow entrance hall; explanatory texts and chronologies are often installed in the fifth room of a typical exhibition path. Museum goers thus stepped into the first gallery of the Makart show with no preliminary introduction to his life or career.

[3] Visitors renting an audioguide could learn that the figures surrounding the emperor in the Entry of Charles V were prominent Viennese, recognizable in the final version of the picture hung in Hamburg. Since most of the faces in the preliminary sketches on display were blank ovals, obtaining any further information about those faces required a visit to the shop to search for the reproduction of the Hamburg painting in the catalogue (67–8). A dozen Viennese women's faces have recently been identified in the superb study by Doris H. Lehmann, Historienmalerei in Wien: Anselm Feuerbach und Hans Makart im Spiegel zeitgenössischer Kritik (Cologne / Weimar / Vienna: Böhlau, 2011), 165–84, figs. 94–125.

[4] Another Austrian's works mounted outside Memorial Hall for the Centennial exhibition – a pair of bronze Pegasus statues by Vincenz Pilz – remain in Fairmount Park today. The sculptor's winged horses were mocked by the Viennese when installed briefly on the roof of the new State Opera; Robert H. Gratz, a wealthy Philadelphian, saved them from destruction and bought them for his city. A campaign to sell Catherine Cornaro to Philadelphia failed, and Makart's dealer H. O. Miethke sold it to Berlin in 1877.

[5] Stephanie Auer cites records from the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Zentralarchiv, on the purchase and sale of the painting in her fine essay for the Belvedere catalogue, "Caterina Cornaro: 'The Dearest Painted Queen'" (54 and n.41). On the Makart painting, see also Candida Syndikus, "'Aber Caterina schlägt alles' – Hans Makart inszeniert einen venezianischen Traum" in Zwischen den Welten: Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte für Jürg Meyer zur Capellen. Festschrift zum 60. Geburtstag, Damian Dombrowski, ed., with Katrin Heusing and Alexandra Dern (Weimar: VDG, Verlag und Datenbank für Geisteswissenschaften, 2001), 262–80.

[6]Makart: Triumph einer schönen Epoche, Klaus Gallwitz, ed., exh. cat. (Baden-Baden: Staatliche Kunsthalle, 1972). Two years after the Baden-Baden show, Gerbert Frodl published Hans Makart: Monographie und Werkverzeichnis, with a contribution by Renata Mikula (Salzburg: Residenz, 1974). Frodl is currently at work on a new Makart catalogue raisonné.

[7] The three-part Plague in Florence became the property of Makart's dealer Georg Plach in January 1869. Taking advantage of the publicized "rejection" by the Salon, Plach showed the triptych in the Paris gallery of Goupil & Cie. He then exhibited it in Cologne, Leipzig, and Dresden before selling it in 1870 to Horaz von Landau in Florence. In 1940 Benito Mussolini responded to pressure from the Germans and confiscated the Landau-Finaly villa and contents (including the paintings); he donated the Plague in Florence to Hitler for his planned museum in Linz. Collector Georg Schäfer acquired the three paintings in the Swiss art market in 1970.

[8]Time magazine (February 25, 1929) reported the weeding of the Metropolitan pictures under a headline, "Good Riddance," and called the thirty-foot-long Makart "garish and breezy as a circus poster." The full-size Hunting Party of Diana is currently in storage at the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art; the Metropolitan kept its other, smaller Makart, The Dream After the Ball , part of the Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Bequest in 1887. The Hunting Party of Diana sketch in the Belvedere exhibition was – like a number of other paintings in the show – among the 52 Makart paintings destined for the Führermuseum in Linz. To see all 52 objects, click here, then on "Database," and on the Linz Collection entry screen, enter "makart" in the full text search box. Hermann Göring, in addition to The Falconer – a forty-fifth birthday gift from Hitler in January 1938 – owned a smaller replica of Hunting Party and eight other Makart paintings. On Hitler's attraction to Makart, see Birgit Schwarz, Geniewahn: Hitler und die Kunst (Vienna: Böhlau, 2009), 53–4. Schwarz meticulously traces the information that led Hitler to imagine that he and Makart had in common not only the early loss of a father – which was correct – but unrecognized genius that led to their rejection by the Vienna Academy.

[9] Katharine Lovecky contributed an outstanding essay to the Belvedere catalogue: "Hans Makart: The Wagner of Painting?" (181–95). She discusses the triad of Wagner, Semper, and Makart, the artist's arrival in Bayreuth for the premiere of the Ring in August 1876, and his visual interpretation of its scenes, noting that his ceiling design predates the first performance of the entire tetralogy. Lovecky's essay can be read in conjunction with the section on the Ring in the Wien Museum catalogue, where the three exhibited paintings from the Latvian National Museum of Art, Riga, are illustrated.

[10] According to Rainald Franz's useful catalogue essay, the family had rejected Hitler's offer of 600,000 Reichsmark (estimated at 3 million Euros today) for the ensemble, but finally sold him the ceiling for only 12,000 in 1942; Franz cites Elvira Konecny, Die Familie Dumba and ihre Bedeutung für Wien und Österreich (Vienna: VWGO, 1986). The six wall paintings survived the war in hiding, and the family sold them in 1971; see Rainald Franz, "'Er schritt immer vom Neuen zum Neuen fort': Hans Makarts Ausstattung des Arbeitszimmers für Nikolaus Dumba," Hans Makart: Malerfürst, exh. cat. (Vienna: Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien, 2000), 80. In Franz's essay for the Belvedere catalogue, the captions in his reconstruction drawing (fig. 5) for the allegories of Agriculture and Science are switched; the excellent photographs of the paintings following the essay are correctly captioned.

[11] Lehmann, Historienmalerei in Wien, 64–8, and figs. 24, 25.

[12] The only navigation tool for the Belvedere catalogue, without index or catalogue numbers, is the table of contents. It may help to note that the unnumbered list of Makart works in the show is in chronological order, and other artists' works are listed in alphabetical order. If an illustrated work is in the show, the caption includes measurements.

[13] Wolfgang Kos, director of the Wien Museum, explores that analogy in the final catalogue essay on superstars of art: Warhol, Joseph Beuys, and Damien Hirst (126–35).

[14] With his hand on his lapel, Makart's self-image, were it not for the oblique gaze, could be thought of as a fusion of two masterpieces in the Alte Pinakothek that he would leave behind in Munich: Dürer's Self-Portrait and Raphael's Bindo Altoviti, once thought to represent the painter himself.

[15] "Über den Makartismus, pathologische Erscheinung der Neuzeit," sheet from Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Zentralarchiv, Nachlass Feuerbach. The quoted text reads "Dieses diarrhöeartige Produzieren in seiner asiatischen Trödelbude mißfällt mir, und wird außer Kurs kommen" (165). See also Lehmann, Historienmalerei in Wien, 93–101.

[16] Doris H. Lehmann, "Maler und Stratege: Hans Makarts Weg zum Erfolg" (Painter and Strategy: Hans Makart's Path to Success) in Makart: Ein Künstler regiert die Stadt, 50–57.

[17] A catalogue essay by Werner Kitlitschka offers an extraordinarily clear look at the patrons and painters at work in Vienna after the emperor signed the decree on December 20, 1857, authorizing the razing of the old fortifications, an act leading to the feverish building, painting, and sculpting that continued until World War I.

[18] The play was Arria und Messalina by Adolf von Wilbrandt, which had its premiere at the Hofburgtheater on December 14, 1874. Alexandra Steiner-Strauss wrote the fascinating essay accompanying this section, "Kulissenzauber und Bühnenstars." She points out that Piloty's attachment to the theatre had been passed on to his pupil. Discussing the opera and theatre director Franz von Dingelstedt and his view of the stage as "live history painting," Steiner-Strauss mentions that his work in Vienna was compared to his predecessor by critics as "a change from drawing to color" (95). On Makart's painting of Wolter as Messalina, Steiner-Strauss sees a resemblance to Antonio Canova's Pauline Borghese or, more precisely, to Heinrich Dannecker's Ariadne on the Panther (1804–14; Liebighaus, Frankfurt), a copy of which was in the collection of the actress (99).

[19] An unusual and enlightening coda to the exhibition was the panel in the exit corridor on Makart's reception: all the covers of his catalogues were reproduced, as well as the cover of Frodl's 1974 catalogue raisonné. A last measure of the artist's celebrity was a note on Google hit statistics – 273,000 for Makart, 5,850,000 for Gustav Klimt – and a Google n-gram view.

[20] "Hans Makart und die Sezession," reprinted in Ludwig Hevesi, Acht Jahre Sezession (Vienna: Konegen, 1906), 268.