The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Gemito: Le Sculpteur de l’âme napolitaine

Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris

October 15, 2019–January 26, 2020

Gemito. Dalla scultura al disegno

Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples

September 10–November 15, 2020

Catalogue:

Jean-Loup Champion, ed., with texts by Sylvain Bellenger, Jean-Loup Champion, Cécilie Champy-Vinas, Mariaserena Mormone, Barbara Musetto, Carmine Romano, Maria Tamajo Contarini, Angela Tecce and Isabella Valente,

Gemito: Le Sculpteur de l’âme napolitaine.

Paris, Éditions Paris Musées and Flammarion, 2019.

226 pp.; 200 illus.; bibliography; exhibition checklist.

€35 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978–2–7596–0446–3

During the fall of 2019 and the winter of 2020, the Petit Palais in Paris mounted a significant exhibition of 120 works by the Italian realist sculptor Vincenzo Gemito (1852–1929). The exhibition should have been long concluded by the time of the publication of this review, as it was expected to travel to the Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte in Naples and to be displayed there from March 15 until June 16, 2020. However, the COVID-19 pandemic prevented the exhibition from being presented to the public in Naples during those dates, and instead the show was postponed until this fall. I was privileged to see the exhibition just before COVID-19 rules were in place, when Americans were still permitted to visit Europe and the Petit Palais was packed with unmasked Saturday visitors.

Gemito is by far the best-known and most brilliant Neapolitan sculptor of the second half of the nineteenth century. He was abandoned by his birth parents at the ruota dell’Annunziata in Naples on July 17, 1852, and he was given the surname “Gemito,” or “he who moans.” This seems to be an ironic foreshadowing of his adult life, wherein he would see the death of two of his closest lovers, and in which he would suffer several mental breakdowns. In any event, Gemito was adopted by a poor couple, and he later formed a close relationship with his adoptive mother’s second husband, Masto Ciccio (Francesco Jadicicco) (12–13). Gemito was able to receive his formative training in sculpture from Emanuele Caggiano (1837–1905) and Stanislao Lista (1824–1908).[1] Ancient works at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli and traditional folk crèche figurines that were popular in Naples were other formative references for the young sculptor.

At the age of sixteen, Gemito set up his own studio and soon afterwards created his first independent and significant work, The Card Player (ca. 1869; fig. 1), one of the first of his noteworthy treatments of Neapolitan ragazzi (youths) and scugnizzi (street urchins). These works were followed by portrait commissions of artists and luminaries, such as his well-known and sympathetic portrait of Giuseppe Verdi (1873; fig. 2). He gained notoriety in Paris at the Salon of 1877, where his Neapolitan Fisherboy (1878; fig. 3) was the very definition of a succès de scandale.

The exhibition in Paris began with images of Neapolitan fisherboys by non-Italians (fig. 4). The French interpretations on display in the opening space depicted romantically pretty fisherboys who do everything but their work: they dance the tarantella (Francisque Duret, Young Fisherman Dancing the Tarantella (Memory of Naples), 1832, bronze, Musée du Louvre, Paris); choke and abuse a turtle (François Rude, Young Neapolitan Fisherman Playing with a Turtle, marble, 1833, Musée du Louvre, Paris); sleep languorously along the beach (Antonin Moine, Sleeping Neapolitan Fisherman, 1838, bronze, private collection, Paris); and listen for the sea in a conch shell (Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Fisherman with a Conch Shell, 1858, patinated plaster, Petit Palais, Paris). In these works, fishing nets become decorations, something to sit or sleep on; castanets, religious medallion necklaces, and floppy hats seemingly knitted by someone’s nonna abound. No evidence of caught fish appear in any of these works. In other words, these sculptures are typical romantic stereotypes of Italian children as pious but nonetheless lazy and uneducated, so much so that once at the sea they clearly cannot concentrate for two seconds on the job at hand. Not included in this grouping was Gustave Courbet’s Fisherboy Scouting for Sculpin (1862, bronze, Place Gustave Courbet, Ornans), likely because he was the only French artist to get it right; he depicted a child looking down into the water and fishing with a spear. Courbet also produced the rare French example in this genre not tied to “the other” in southern Italy by the artwork title or through the inclusion of clichéd accoutrements. The “sculpin” in the title of his work refer instead to a type of fish commonly found in the Loue River near Ornans, which was, for Courbet, as local as one could get.

In contrast to the romanticized French works, Gemito’s Neapolitan Fisherman (fig. 3) contains none of the stereotypical trappings associated with this artistic type. As a Neapolitan himself, Gemito must have found such paraphernalia attached to these working children ridiculous. Instead, his Neapolitan fisherboy wears a fishing net around his waist, where it could be used to actually catch fish, and to store them there during his return to the market. His pose is completely believable, as he rests squatted while he calmly subdues the still squirming fish, whose tail remains taut. Life, youth, survival, and death are all presented here in two breaths, captured by the also taut belly of the boy who breathes in as he kills the fish, its gills emptying out. When shown in the Salon of 1877, French critics were unkind, calling the child a “cretin” and a “little monster,” we assume because he is shown actually doing his job (91–92). In fact, the negative criticism was less about the sculpture at hand, and more about the fragile sensibilities within nineteenth-century French culture, sensibilities with which many Italians, by the post-Risorgimento period, had already dispensed. If in fact the child portrayed seems to lack grace, it was not because Gemito was incapable of creating graceful figures; it was because in reality, catching a squirming, dying fish in one’s hands is not a graceful act. Of course, there is no such thing as bad publicity, and Gemito was able to capitalize on both the negative and positive reviews of his work at the Salon de Paris.

Working and non-working children made up the better part of Gemito’s contributions to the Paris exhibition. His Card Player (fig. 1), depicts a child who is shoeless, shirtless, and wearing a pair of pants full of holes. He pores over a hand of cards. Shown at the Exhibition for the Promotion of the Fine Arts in Naples in 1870 (under the original title Vice), The Card Player was an immediate success and directly purchased by the Royal House of Naples for the palace of Capodimonte (33, 47). The elegant Shepherd of the Abruzzi (ca. 1873) illustrates a working child who needs little more than a shepherd’s cap, a net across his shoulder, and a concerned gaze that looks down and over his flock to express a full range of vivacity and emotive quality (fig. 5).

One of the most engaging heads of a scugnizzo is entitled Idiot (1870; fig. 6, left). It is unclear if the title is related to a medical diagnosis or a personality trait, but the child’s tranquil expression and soft features deny the moniker in either case. The work is one of the best examples of the tactile qualities of Gemito’s terra cotta sculptures. Nondescript folds of lumpy clay at the neck suggest rags of clothing, while smooth and soft applications of the material, with passages that result in the smallest indication of a tired, puffy eyelid or an inflamed upper lip, give life and breath to these scugnizzi figures. Their open mouths, gasping for precious air, as in Sick Child (1870; fig. 6, right) and Head of a Young Girl (1870–72; fig. 7, right) remind us of the poverty and illness that plagued the children of the Neapolitan streets, the very streets that Gemito knew so well himself, conditions that are completely forgotten when one looks at sculptures by foreign artists who depicted these same subjects. The flawless Young Moor (1872; fig. 8) is an example of how Gemito elevated these young children to a position, and into a type of presentation, that was too often reserved by other artists for the refined elite.

When Gemito turned to portraying famous cultural figures, his portrait busts lose nothing of the high quality of expression employed in the ragazzi and scugnizzi. During a visit to Naples in 1873 for the production of his operas Don Carlo and Aïda, Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) sat for a portrait with Gemito (fig. 2, right); it became his most celebrated portrait. Legend has it that during one of their sittings, Verdi paused for a few moments to play some chords on the pianoforte; this pose inspired the lowered head and concentrated gaze seen in the bust, which can be read in so many other ways, including as representations of intent listening, and as deep meditation (53). Gemito’s bust of Mariano Fortuny (1838–74), created one year before the painter’s death in 1874 while he was staying in Naples at Portici, captures his fine, solid features and the sensation of thought, and nothing of the malaria that would soon claim his life (fig. 9). In Paris, where Gemito sojourned from 1877 until 1880, he would sculpt elegant busts of Ernest Meissonier (1815–91) and Paul Dubois (1829–1905), among others.

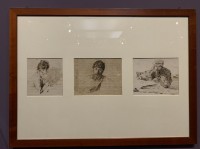

Without naming names, I have seen enough nineteenth-century drawings by sculptors during my thirty years in this field to feel confident in stating that few make excellent draftspeople. The best of them draw with a chisel. In the case of Gemito, however, the drawings and works on paper from his hand go above and beyond the typical sculptor’s abilities. Three small ink on paper drawings depicting Gemito’s lover Mathilde Duffaud framed alongside two self-portraits prove his abilities in fine line ink drawing (fig. 10). His skills with watercolor were no less impressive and are exemplified by Self Portrait with Mathilde Duffaud from 1881 (signed 1909, Naples, Collection Intesa Sanpaolo) created in the year Mathilde died and reworked twenty-eight years later (fig. 11). A luscious drawing of another type of ubiquitous scugnizza entitled Gypsy (1885, charcoal, red chalk, watercolor and gouache on paper, Collection Intesa Sanpaolo, Naples) is beautifully drawn. Her gray eyes and parted lips enchant the viewer (fig. 12). The large-scale drawn portraits of the Bertolini children without a doubt prefigure the works of Balthus, and this is seen in particular in the portrait of Laura Bertolini, whose long legs and rounded thighs hint at her flowering into adolescence (fig. 13).

Towards the end, the exhibition surveys Gemito’s exploration of the antique, which began around 1883. In comparison with the earlier realist works, and even works from the same period such as the bust of his lover Anna Cutolo (ca. 1886, marble, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples), the classical works follow the language of the antique almost too closely. It is difficult, frankly, to see the hand of the artist and the vivacity of his earlier works in these classical productions. His small-scale rendition of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (after 1884) was produced with over-the-top surface detailing and a cold fussiness that belies his lively and loose works from the early 1870s (fig. 14). The best of Gemito’s classically influenced works is without doubt Medallion with the Head of Medusa (1911; fig. 15). Here one sees, in the wild hair, contorted facial muscles, open mouth, and twisted snakes, remnants of the energy of his earlier concepts.

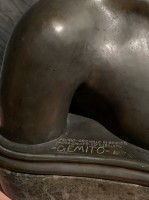

In 1883, around the same time as Gemito rediscovered the antique, he also realized a professional goal of creating his own foundry in Naples (182). A fine bust entitled Portrait of a Young Girl (1913–22) exhibited towards the end of the exhibition in Paris contains the markings of his personal bronze production (figs. 16, 17). Inscribed in the bronze is the phrase, “first original in bronze created and executed by me—Gemito” (fig. 18). This work is also an example of the best of Gemito’s late production in bronze. While the late classical-style works border on pastiche, Ritratto di fanciulla embodies both the conventional elements of the classicized nude with the modern touches (the loose chignon; the pierced ear; the turn of the head towards the left shoulder; the broad, toothy smile) found in his best works.

The exhibition catalogue which accompanied the Paris venue was edited by Jean-Loup Champion, and includes essays by Champion along with Sylvain Bellenger, Cécilie Champy-Vinas, Mariaserena Mormone, Barbara Musetto, Carmine Romano, Maria Tamajo Contarini, Angela Tecce, and Isabella Valente. It is lavishly printed in full color, with two hundred illustrations. The order of the essays follows the order of the exhibition closely, and the contributions expand upon themes referenced the exhibition, including the art of portrait sculpture (by Champy-Vinas); Neapolitan sculpture at the Universal Exhibition in 1878 (Valente); Gemito’s difficulties with mental illness (Bellenger); and his work as a founder (Romano). All of the essays are clear, lack jargon, and place biography, French and Italian history, and art history at the forefront of the discussions. The catalogue does, however, suffer from the lack of a proper index. The exhibition checklist refers readers back to the page where an artwork is reproduced, but not to all of the pages where the artwork is discussed. Though it requires a lot of annoying back-and-forth flipping around to find sections on specific artworks, the essays and the illustrations make it a significant resource on the life and work of Gemito nonetheless.

In 1994, a former professor of mine (who has since passed from this realm and into another) gave me a copy of an exhibition catalogue entitled Chiseled with a Brush: Italian Sculpture, 1860–1925, from the Gilgore Collections. He passed it along to me because he knew I was starting to develop an interest in nineteenth-century sculpture at that time. Though I was unable to see the actual exhibition in Chicago and Denver, the catalogue included many great Italian artworks and sculptors, including Giuseppe Grandi (1843–94), Ettore Ferrari (1845–1929), Giulio Monteverde (1837–1917), Medardo Rosso (1858–1928), and Gemito, among others. Gemito made up the largest portion of the Gilgore Italian sculpture collection, and it was his artworks (and Rosso’s) that I would later see most often in museum collections. It was Gemito’s works that were the stars of that presentation, and I wanted to see more of them in person. I have kept that catalogue on my front bookshelf for the past twenty-six years, at the ready, as it were, waiting for another exhibition to come around and expand upon the earlier one that I did not see except in pictures. Gemito: Le Sculpteur de l’âme napolitaine satisfied that long-held desire to experience Gemito’s exquisite works, and the exhibition catalogue will surely inspire new scholars of sculpture to discover his oeuvre.

Caterina Y. Pierre, Ph.D.

Professor, City University of New York, Kingsborough Community College

Visiting Associate Professor, The Pratt Institute

caterina.pierre[at]kbcc.cuny.edu

cpierre[at]pratt.edu

[1] In addition to the catalogue for the exhibition under review here, see also Ian Wardropper and Fred Licht, Chiseled with a Brush: Italian Sculpture, 1860–1925, from the Gilgore Collection, exh. cat. (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1994), 81. For an excellent study of the history of children being abandoned at ruotas, or wheels, in Italy, see David I. Kertzer, Sacrificed for Honor: Italian Infant Abandonment and the Politics of Reproductive Control (Boston: Beacon Press, 1993).