The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

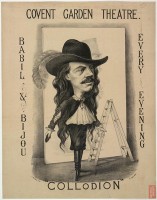

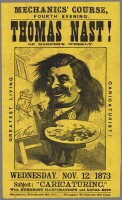

On the day after Christmas in 1872, a French caricaturist known as Victor Collodion, recently banned in Paris for mocking the president of France, debuted on the London stage. Speaking no English and appearing only momentarily amid a four-hour extravaganza, he became a surprise overnight sensation. A show bill featuring his self-portrait preserves perhaps the sole visual record of his popular act (fig. 1). Garbed in knee-high leather boots, a velvet jacket with diamond-slit sleeves, flaring lace cuffs, and a wide-brimmed hat with a feather plume atop a long mane of flowing hair, Collodion exuded the swashbuckling bravado of an Ancien-Régime guardsman, though armed with drawing charcoal rather than a sword. During each performance, he balanced on a stepladder to scrawl two huge caricatures at breakneck pace, one per side of a twelve-foot-high papered panel. Nimbly dashing off enormous portraits of politicians and celebrities, Collodion caught the public’s fancy, soon inspired a flurry of imitators, and ignited a theatrical craze for rapid-fire caricature.

Before even one year had passed, Collodion’s meteoric career ended in tragedy, but the type of performance he popularized, often called “lightning artist” routines, endured well into the twentieth century as a distinct show-business genre (vid. 1). Adopting myriad professional labels, such as “lightning caricaturist,” “instantaneous cartoonist,” “impromptu artist,” “electric caricaturist,” “express cartoonist,” and “rapid sketch artist,” among others, lightning artists proliferated in many spheres of live entertainment.[1] Especially popular in the anglophone world, with its comparatively tolerant laws regarding political censorship, by the turn of the century lightning-artist acts were common in Australia, Britain, Canada, and the United States. “In England, a drawing act is quite as common as the song and dance,” noted one lightning artist as late as 1922. While in the United States, the same artist observed, the “modern vaudeville manager is keenly alive to the interest in pictures drawn before an audience.”[2]

In addition to their continued popularity on the stage, some lightning artists, a generation after Collodion’s fleeting moment of celebrity, exerted an outsized influence on the nascent cinematic medium of animation. Beginning with the groundbreaking scholarship of Donald Crafton, and more recently with the increased application of performance studies to the early history of animation, scholars in this field have repeatedly observed the profound impact of lightning artists.[3] Thus, in their respective edited volumes from 2019, Scott Curtis writes that “in terms of the conventions or iconography of animation during its early period (1908–1913), the vaudeville lightning sketch is perhaps the most important influence,” and Annabelle Honess Roe notes that even “in later animations that don’t include the act of lightning sketching, the relationship between animation and vaudeville performance is still apparent.”[4]

Film scholars, understandably, have attended more to the influence of lightning artists on early cinematic subjects and techniques than to the origins or prior history of such pictorial and theatrical practices themselves. As a result, lightning artistry has often been treated vaguely as a timeworn stage convention that emerged around the middle of the nineteenth century along with the professionalization of the entertainment formats known as music hall in Britain and vaudeville in the United States.[5] However, the rise of lightning artists does not, in fact, stretch back so far. “It was only in the 1870s and early 1880s that a variety of practices coalesced into the widely recognized ‘lightning cartoon’ music-hall act,” observes Malcolm Cook, whose book Early British Animation: From Page and Stage to Cinema Screen (2018) provides the most thorough and insightful discussion to date of lightning artists in Britain and their involvement with early motion pictures.[6]

This essay describes more precisely the circumstances of that coalescing of practices through a discussion of the seminal, yet overlooked figure of Monsieur Collodion. It also considers the sudden rush of imitators and rivals of Collodion that created an international “sensation” around lightning-artist acts in 1873.[7] Finally, it discusses the reliance of early lightning artists on photographic technologies in the realm of portraiture, especially cartes de visite and cabinet cards. In this way, the essay also seeks to demonstrate how formal influences flowed not only from the tradition of live theater to the deployment of new photographic technologies, but in the opposite direction as well. That is, just as lightning artistry influenced early animation and motion pictures starting in the 1890s, the emergence of lightning artistry itself in the 1870s relied profoundly on developments with the mass visual culture of still photography.

Victor Collodion and the Origins of Lightning Caricature

Artists surely made drawings in front of live audiences before Collodion introduced his unusual lightning-artist act in France around 1871. For centuries, European painters, especially portraitists needing to keep sitters with entourages entertained, had hosted groups in their studios while at work.[8] With the rise of art academies, instructors demonstrated drawing and painting techniques to gatherings of students. However, such situations seem fundamentally distinct from the fast-paced, comical drawing performance Collodion presented onstage nightly to entertain hundreds of paying customers. Intriguingly, the English cartoonist Frank Bellew proposed a similar entertainment in New York in 1861, announcing a public lecture called “Caricature” with the novel feature of being “illustrated by humorous diagrams made at the moment,” but it seems it never materialized.[9] Whatever forerunners may have preceded Collodion in this line, his act prompted a wave of lightning artists and he became, for a brief time, the definitive reference point for such entertainments.

Information about Victor Collodion is scarce. He was born Victor-Alexandre-Louis Malfait in Lille on June 12, 1842. His birth certificate lists his father as a clothmaker, but little else is known about his family or childhood.[10] Accounts differ regarding the location of his upbringing, but several sources suggest that his first professional training came as he pursued “the trade of photographer.”[11] According to one friend, Collodion began work as “an apprentice photographer in Clermont.”[12] Another acquaintance in Saint-Étienne recalled that when Collodion arrived there in 1866, he had retreated from Paris, “where photography seemed not to have enriched him.”[13]

This photographic expertise connects with the presumed meaning of Collodion’s pseudonym. The term “collodion”—derived from the Greek word kollodis, meaning gluey—referred to the syrupy liquid poured onto plate glass to create transparent emulsions that enabled great advances in mid-century photography.[14] Compared to earlier glass-negative techniques, collodion processes yielded crisper images at quicker speeds. Thus the stage name “Collodion” could connote accuracy and rapidity in image making. As one friend noted, Malfait “called himself Collodion, no doubt to better inform the public with what instantaneity he made a portrait likeness.”[15] The full pseudonym “Victor Collodion” might suggest victory over the collodion process itself, perhaps implying something akin to “better and faster than a camera.”[16]

Before turning twenty, Collodion already belonged to a youthful bohemian crowd in Paris orbiting the Théâtre de l’École Lyrique, one of the few théâtres d’élèves, private “training theatres” available for rent, “where young amateurs practice the dramatic profession.”[17] The songwriter Félix Savard chronicled this theatrical institution and its leading figures, noting their fondness for raucous productions as “hilarious and burlesque as possible.” Savard briefly mentions Collodion among the denizens of the humble Café Prud’hom, an establishment near the École Lyrique often packed with garrulous playwrights and aspiring “actors from the provinces” seeking to make reputations in Paris: “At all the tables, in a word, we are talking theater, and in one corner the caricaturist Victor Collodion is making drawings of his neighbors.”[18]

Not merely an onlooker, Collodion also pursued a theatrical career as a singer, lyricist, comedic playwright, and director. In Paris in 1863, he helped organize La Mi-Carême, an annual mid-Lent festival, and in Mâcon in 1865 he published an anthology of comic songs.[19] In 1867, with Savard, he cowrote and codirected a one-act farce with songs, Un crime dans une valise (A crime in a suitcase), at the Théâtre des Folies-Dramatiques, a leading Parisian venue for comic operas and other humorous musical fare.[20] Though an impressive item on his theatrical résumé, this short-lived production probably did little to remedy his financial hardships, described by several acquaintances. One noted that in Paris Collodion grew skilled at sleeping “fully clothed on a mattress on the floor, in the sad, cold, and already cramped bedroom of a broke friend.”[21] Perhaps his precarious economic situation influenced his decision to work largely outside of Paris after 1867. Collodion’s later theatrical productions, largely musical reviews and comical “vaudevilles,” such as Le Parapluie de Monriflard (The umbrella of Monriflard) and La Grande dépêche (The great dispatch), were mounted in provincial cities ranging from Le Mans and Lille, in the north and east, to Bordeaux, Marseille, Nantes, and Tours, in the south and west.[22]

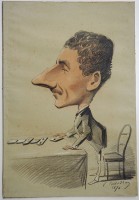

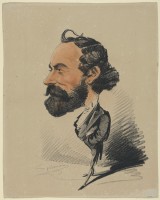

Along with his itinerant theatrical ventures, Collodion also did a brisk business as a portrait caricaturist. After arriving in Saint-Étienne in 1866, he wandered “from café to café, taking portraits by the minute.”[23] By the end of his sojourn, a local newspaper reported that he had established a fixed headquarters at the Café Ombry, charging two-and-a-half francs per caricature.[24] In 1869 in Vichy, where he published a self-caricature (fig. 2), he seems to have heralded his presence at local cafés with a parasol trimmed in pink fabric, which surely made for a distinctive ensemble along with his “brilliant Charles IX–style costume” of black velvet.[25] In some cities, his portrait sessions became a more formal service. In Bordeaux, for example, he opened a studio where he drew caricatures daily from noon until two.[26] A few surviving drawings by Collodion, following the French caricatural convention of big heads on small bodies, exemplify this sort of portrait work (figs. 3, 4).[27]

Collodion also worked extensively as a lithographic artist. By 1864, he was referenced as the “usual draftsman” for the Mâcon lithographer Decourt, who produced all manner of printed materials for local businesses, from theater posters to liquor labels to Franciscan devotional images.[28] However, Collodion’s chief lithographic pursuit soon became journalistic caricature. A friend recalled that the scandalous success of André Gill’s covers for the comic magazine La Lune (The moon), a recurring thorn in the side of the French government, inspired Collodion to work in this vein.[29] Between 1867 and 1872, Collodion designed covers for a string of at least eight different journals, some of which he founded and edited himself.[30] Forbidden by law from deriding government officials and always keeping one foot in the professional theater world, Collodion, not surprisingly, chiefly caricatured performers, musicians, and impresarios.[31]

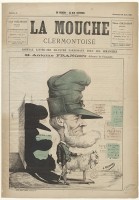

His first comic pictorial seems to be La Mouche (The fly), published in Clermont starting in the summer of 1867 (fig. 5).[32] A friend recollected that “an adventurous printer” fond of Gill’s work helped Collodion create a journal similar to La Lune.[33] Such endeavors were less common outside of Paris. “What La Mouche is trying is almost unheard of in the provinces, because very few attempts of this kind have managed to succeed,” noted one local paper.[34] Lasting about half a year, the longest of his journalistic endeavors, La Mouche may have been fairly popular, if not lucrative, since it was later remembered as “a little illustrated literary journal, which was much in vogue.”[35] Even La Lune itself took favorable notice of Collodion’s work in La Mouche, ranking him alongside the best of Gill’s Parisian disciples.[36] There is even a possibility that Collodion initially envisioned his provincial journal arranging a formal association with La Lune since, early in its run, Collodion listed Gill among the contributing illustrators.[37]

After La Mouche, Collodion’s lengthiest association with an illustrated journal was with Le Gaulois (The Gaul) in Bordeaux.[38] Here, perhaps for the first time, Collodion ran afoul of the strict French censorship laws. Sensing conflict, or perhaps courting it, in late December he depicted himself with four fellow contributors to Le Gaulois attempting to cross toward the new year of 1869 on a rickety plank without plunging into the “politics” and “defamation” swirling in a dark, ominous chasm beneath them (fig. 6). This picture of the journal’s precarious condition proved prescient.

In the new year, as it grew more brash, Le Gaulois repeatedly ran afoul of the authorities. In early February, officials apparently changed their minds about the acceptability of Collodion’s caricature of Henri Rochefort, a radical playwright and journalist who had recently fled to Belgium to avoid imprisonment and who stood with Gill as a conspicuous critic of the Second Empire regime (fig. 7). After its dissemination, this issue of Le Gaulois was banned from public display—which in turn heightened demand for it and apparently occasioned a second printing.[39] Then, in March, officials denied Collodion permission to publish a caricature of Jules Mirès, the disgraced financier and publisher. In response, for what seems to have been the paper’s swan song, Collodion portrayed himself ducking away from a large razor labeled “censure” looming menacingly above his head, while he holds both an oversized porte-crayon and a blacked-out copy of the journal (fig. 8).[40]

With these provocations, Collodion probably drew further inspiration from Gill, whose caricatures had led to the banning of La Lune in 1868, along with fines and criminal lawsuits against both Gill and his publisher, François Polo, helping to make both men heroes within antiestablishment circles. At least one writer later placed Collodion in this mold of a democratic champion, calling him “a man who had served democracy,” specifically for his work with the journal Le Contribuable (The taxpayer) in Rochefort in 1869.[41] In these years, traveling from city to city, Collodion contributed to local humor sheets for a few months at a time. For instance, he worked with Turlututu (Tra-la-la) in Moulins in the spring of 1868, Bordeaux pour rire (Bordeaux for laughs) in Bordeaux in the spring of 1869, L’Indicateur (The indicator) in Arcachon in the fall of 1869, Le Programme de Vichy (The Vichy program) at some point in 1869, and Le Pilori (The pillory) in Nantes in the fall of 1870.[42] Although Collodion’s frequent moves between cities perhaps suggests a sequence of failed publishing endeavors, it is probably more accurate to view his constantly shifting journalistic endeavors as just one element within a roving and versatile multimedia project rooted in satirical comedy.

Combining these various artistic pursuits, around 1871 Collodion began developing a performance routine in which he drew oversized caricatures of celebrities at high speed. Having apparently honed the act in multiple venues, he brought it to Paris in 1872. The newspaper L’Événement announced his arrival and predicted his success, noting that Collodion, “better known in the provinces than in Paris, will execute in less than fifty seconds an artist’s caricature, double life-size. Le Havre, Bordeaux, Lille, Nantes, and Marseille have already applauded Mr. Victor Collodion, remember this name!”[43]

Arsène Goubert, manager of the Alcazar, a popular café concert in Paris, hired Collodion as part of a variety lineup.[44] In the meantime, Collodion practiced making his caricatures yet larger. One friend recounted how Collodion’s act required “great dexterity and much practice” since, “like a theatrical scene-painter, the executor of such gigantic drawings cannot sense the effect they produce. The nose of his subject is three feet long, the eye is as big as the head of an ordinary man; and then you have to act quickly, very quickly, and not get mixed up.” According to the same source, Goubert paid Collodion “ten francs per evening. What a joy! It was the first success for the poor boy.”[45] Another friend recollected that immediately “the crowd came running” to see Collodion’s unusual routine.[46] But this happy state of affairs did not last long, for a contretemps with government censors abruptly altered Collodion’s career trajectory.

The dispute concerned an alleged caricature of Adolphe Thiers, the president of France, who was also one of Gill’s favorite targets. French law outright forbade the ridicule of public officials. Also, whether published or performed, all caricatures required prior approval from government censors.[47] Although some viewers described Collodion as improvising his caricatures, such an exhibition would have been illegal. Almost certainly, as one acquaintance recalled, “Collodion submitted, ahead of time to the censors, a sketch of the caricatures he wanted to make.”[48] However, on the night of November 8, 1872, Collodion dashed off a drawing that might have departed from his authorized submission. The Parisian theatrical journal Le Figaro closely followed the imbroglio: “The Alcazar is very agitated tonight. Here’s why: an artist named Collodion improvises each evening, on a drawing board, caricatures of familiar comedians. The day before yesterday, after caricaturing some artists, Mr. Collodion ended his session with a portrait of a character whose features a number of people have recognized . . . the president of the Republic.”[49] Accounts differ widely regarding how many patrons interpreted the drawing as Thiers—perhaps the entire audience, perhaps just one killjoy policeman.[50] Either way, according to Le Figaro, the incident was “reported through government channels to the Prefect of Police” with the result that “the Alcazar has been ordered shut for eight days.”[51]

Goubert and Collodion quickly protested that “the incriminating caricature was intended to represent the features of the actor Léonce” rather than the French president.[52] Any confusion resulted, they claimed, from the fact that the tenor Léonce, famous for his comical roles in Jacques Offenbach’s opéra bouffe productions, wore small-lensed, wire-framed glasses quite similar to those of Thiers (figs. 9, 10). “Faced with these denials, the administration has paused; it has ordered an investigation,” Le Figaro explained.[53] In the end, the authorities pardoned Goubert and the Alcazar, which quickly reopened, but held the artist culpable. Collodion was henceforth banned from public performances in Paris.[54] Le Figaro reported ruefully that “Collodion no longer has authorization to make any kind of caricature in public. All because Léonce has the misfortune to wear glasses!”[55]

The Lightning-Artist Craze of 1873

Perhaps an impulsive gaffe, perhaps a misinterpreted drawing, perhaps a deliberate provocation, Collodion’s fateful caricature—whether depicting Léonce or Thiers—stifled his professional prospects in Paris but, simultaneously and unexpectedly, it also opened new opportunities elsewhere. As one London journalist noted, after learning that Collodion “was very recently prohibited from performing in Paris,” it was only natural that in England “everybody will be curious to see an exhibition of his unique skill.”[56] Capitalizing on his sudden notoriety, Collodion quickly achieved success in England far greater than he could have imagined. With the French manager Bernard Latte facilitating the engagement, the actor-playwright Dion Boucicault soon added Collodion to his current show, Babil and Bijou, a five-act “mammoth spectacle” that offered a rich musical score, lavish costumes, and impressive scenic effects, which transported viewers to fairyland, the ocean floor, the moon, and elsewhere.[57]

Although incongruously shoehorned into this production, Collodion’s caricature routine quickly became a star turn (fig. 1). A writer for the London Daily News described Collodion’s enigmatic appearance: “Amongst the many curious incidents which arise in the course of this adventure is the sudden appearance upon the stage of a M. Collodion, who, without any apparent provocation or reason explicable in connection with the story, proceeds to draw in chalk on a large board a caricature likeness of M. Thiers.”[58] For those aware of Collodion’s recent suppression in Paris, his performance surely held added significance, perhaps offering a transgressive thrill from witnessing a forbidden performance, perhaps reinforcing a smugly nationalistic sense of superiority over France. But even without such associations, and without a compelling narrative purpose for Collodion within the show, audiences enjoyed seeing the huge caricatures drawn in furious bursts of activity. Declaring it “one of the most astounding performances I ever saw in my life,” the editor of London’s comic journal Judy described how Collodion “with a piece of black chalk on a white board, sketches with the greatest rapidity, and without a false stroke, a series of caricatures of popular characters.”[59] A writer for the Morning Post reported that Collodion’s drawings repeatedly “awoke shouts of laughter” while mystifying his viewers.[60]

A French visitor to London detailed Collodion’s “superb” routine: “Two assistants brought a large white frame, four meters high by two meters wide, and placed it center stage; another appeared bringing a stepladder.” Then, from the wings, “boldly crossing the vast scene,” Collodion entered, wearing a “soft felt hat with a wide brim, velvet jacket, hussar pants. He climbed the stepladder, holding in his hand a piece of black pastel, as big as an apple.” Collodion set to work abruptly, “crushing his pastel on the canvas, punching with his fists,” and in under two minutes he had produced a large caricature of Prime Minster Gladstone. After his assistants swiveled the frame, Collodion dove into another frenzy of gesticulation, rendering a caricature of the radical trade unionist George Odger. In mere minutes, the routine ended and Collodion “greeted the audience graciously and went backstage.”[61]

On New Year’s Eve, just a week after his debut, Collodion corresponded with a friend in Paris, excitedly sharing news of his enthusiastic reception and his suddenly exorbitant salary. “As for me, I have an immense success at the royal theatre at Covent Garden in Babil and Bijou,” he wrote. “So, my commitment was extended to March 10, when I will go to the Manchester Theater for six weeks for 10,000 francs (!!!) What do you say about the English, hmm?”[62] Collodion’s Manchester contract paid over twenty times more per week than the wages he had briefly earned in Paris at the Alcazar. In addition to this enormous pay raise, Collodion surely enjoyed the lax attitude of the English authorities toward caricaturing government figures; he regularly drew Prime Minister Gladstone and other English politicians. Beyond the reach of French censors, he was also free to repeatedly caricature Thiers, making something of a signature piece from the subject that—deliberately or not—had stirred up such trouble in Paris.

Thus, Collodion began 1873 on a high note, but in the coming months the craze for lightning artistry he had launched spurred rival acts onto the stage. Artists, performers, and theatrical managers rushed to capitalize on the new fad. Shortly after Collodion reached Manchester, he encountered perhaps the first of many imitators, presumably a parodist, advertised as “Signor Cyanide de Potassium.” Since potassium cyanide was used to fix, or neutralize, the wet-collodion development process, this nom de guerre suggested an implicit, if comical, challenge to Collodion.[63] More threateningly, by the end of March a true rival, known as Signor Kalulu, had appeared with a lightning-caricature routine in London’s Marylebone Music Hall as part of a minstrel show organized by Holmes & Gant, who quipped in their advertisements that the troupe would “make no use of ‘Collodion’ in their portraits.”[64]

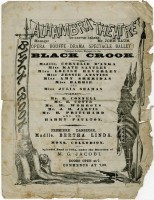

Returning to London in April, Collodion’s popularity grew, as did the number of his imitators. Starting on Easter Monday, he appeared for three months in the city’s reigning “spectacle par excellence,” Black Crook, one of the “big spectacular musical shows” for which the cavernous Alhambra Theatre was then known (fig. 11).[65] Rather than wearing out his welcome, Collodion—now often billed as “The Great Collodion” rather than simply “Monsieur Collodion”—further burnished his reputation. “The celebrated M. Collodion . . . seems to have gained in popularity since his first appearance at Easter, and to have surpassed his former efforts at Covent-garden,” noted The Era, the leading chronicler of the London stage. “He proves to be a great attraction, and is hailed with enthusiasm nightly by crowded audiences.”[66] Indicating the growing familiarity of his routine, during that summer at least two London theaters mounted mock caricature performances that spoofed Collodion’s distinctive act.[67]

In mid-July, Collodion left Black Crook a few weeks before it closed, in order to return to Paris, where on July 26 he married a young singer from Lyon named Françoise Bertillot.[68] These nuptials help explain both his departure from London despite his ongoing success, as well as his late arrival for his next contracted engagement with Lydia Thompson’s English burlesque troupe at the Olympic Theatre in New York. The New York Times noted that Thompson’s upcoming production, Mephisto and the Four Sensations, would feature some specialty acts, “and most important among these will be, it is understood, the instantaneous caricatures of M. Collodion.”[69] However, Collodion did not reach Manhattan in time for his scheduled debut, much to the chagrin of Thompson’s manager, who published apologetic notices promising Collodion’s imminent arrival. Mr. and Mrs. Collodion—the press seems to have never used their legal names—finally reached Manhattan at the end of August, with Collodion joining the cast of Mephisto one week into its slightly postponed run.[70]

This short delay proved immensely costly, for Collodion no longer had the field of lightning artistry to himself. Before he had reached New York, a daunting competitor, as opposed to a clowning imitator, had taken to the stage of a prominent theater—though the details of precisely what transpired remain unclear. Perhaps first attempting to hire Collodion himself, the New York theatrical producer Henry Palmer, either knowingly or unknowingly, instead signed a different French artist living in London, Félix Régamey, to perform lightning sketches in a revival production of the much-imitated blockbuster The Black Crook.[71]

Like Collodion, Régamey had designed caricatures for short-lived, liberal humor magazines before moving to London as a political outcast from Paris. Régamey had been one of the artists working closely with Gill and contributing to La Lune; Régamey and Gill shared credit for a drawing in the magazine as early as 1866.[72] Régamey remained in the French capital as an enlisted soldier through the turbulent months of the Paris Commune. In 1871, he briefly published caricatures in Le Grelot (The bell), sharing the pseudonym “Flock” with Gill, another staunch communard (fig. 12).[73] At some point after the Commune fell, Régamey departed for London, where he had already been getting work by sending sketches to the Illustrated London News.[74] Though he departed Paris before Collodion’s performances at the Alcazar, Régamey may well have witnessed Collodion’s routine in London at either Covent Garden or the Alhambra Theatre.

It is hard to escape the conclusion that Régamey’s promoters in the United States deliberately misrepresented him to the public by conflating him with Collodion, though understandably confused journalists surely compounded this skullduggery.[75] Régamey was trumpeted from Boston to San Francisco as “the French caricaturist, who astonished London during the run there of ‘Babil and Bijou.’”[76] The Minneapolis Tribune recounted the tale of the transgressive depiction of Thiers at the Alcazar in Paris, but mistakenly identified Régamey as the perpetrator.[77] Sam Colville, manager of Thompson’s Troupe, attempted to set the record straight with advertisements calling Collodion “the Original Caricaturist” and asserting his credentials as “the only acknowledged artist of his character of art known in Europe, all others being imitators.”[78] Not surprisingly, hard feelings arose between the two artists. “Rivalry ran high between them, and Collodion charged Régamey with abridging his labors,” noted the World.[79] Régamey’s promoters tried to shift the debate away from artistic precedents by challenging Collodion to meet Régamey publicly in a lightning-caricature contest for bragging rights along with a sizeable prize purse, insisting “that Collodion’s friends shall either put up or shut up.”[80] Apparently no such faceoff transpired, but a war of words continued as it was “hinted by the Collodion side that M. Régamey has his pictures all carefully traced on the paper” before each performance.[81] Soon, however, adding insult to injury, the Thompson Troupe parted ways with Collodion and added a spoof version of his act to their burlesque production Aladdin.[82]

Régamey was not the only rival caricaturist to perform that fall. In Philadelphia, three weeks after Collodion arrived in New York, the impresario Robert Fox debuted another French lightning artist, Edward Jump, a caricaturist long residing in San Francisco who had moved east to work as a newspaper illustrator.[83] “The latest thing upon which theatres have seized is the caricaturist,” observed the World. “There are now three of these sketchers nightly working for amazed audiences at three of our theaters.”[84] Rumors of a fourth lightning artist, “a poor, uneducated Irish boy,” reached the Evening Telegraph, which reported that the young artist “attracts much attention in the streets and barrooms by his talent from crayon sketching.”[85] This was probably Henry or James Carling, immigrant orphan brothers from Liverpool, of Irish parentage, who supported themselves as sidewalk chalk artists.[86] Before the month of September 1873 was over, P. T. Barnum, never one to ignore a popular fad, had “engaged an English artist named Howe to run an opposition to Messrs. Regamy [sic] and Collodion in the fast-color school of portraiture.”[87]

With his New York reception largely spoiled through the marketing machinations of Palmer, Collodion quickly accepted an offer to perform in Cincinnati with The Magic Talisman, a production “just about as near to the ‘Black Crook’ as it can well be, and yet be changed at all.”[88] Claiming to be the “grandest exhibition ever presented outside of New York City,” the show paid well from its lavish budget.[89] Unlike Manhattan, Cincinnati received Collodion with open arms. Each morning, newspapers chronicled his caricatures from the previous night’s performance. From nationally known celebrities to local figures ranging from the mayor to the chief coroner, Collodion’s caricatures enthralled his midwestern audiences.[90] “He produces immense portraits of people in the audience and of prominent people, on a huge blackboard, in one minute and a half. His work creates great enthusiasm everywhere,” noted the Cincinnati Enquirer.[91]

As Collodion entertained in Ohio and Régamey continued to perform in New York, still another illustrator, destined for the greatest success that season as a lightning artist in the United States, prepared to introduce yet another sketch act. Debuting on October 6, 1873, in Peabody, Massachusetts, Thomas Nast, the radical Republican caricaturist for Harper’s Weekly, toured the Northeast and Midwest, lecturing for half a year on the lyceum circuit.[92] Advertisements for Nast’s tour promoted him both as a combative editorial cartoonist as well as a novel lightning artist in the mold of Collodion. Nast’s performance was described as part of a brand new fad, “a just found art, at least in this country,” one advertisement announced. “This ‘instantaneous caricature’ is a comparatively ‘new thing,’—somewhat of a ‘sensation.’”[93] Whereas Collodion and most of his imitators presented short routines within larger theatrical spectacles or variety bills and greatly emphasized the speed of their depictions, Nast had an entire solo performance to fill and, while he did work quickly, he also added more details to his drawings. “He makes of the hurried caricatures, not mere outline sketches, as Régamey and Collodion did, but tinted and neatly finished pictures in colored chalks,” reported the Evening Post.[94]

Although lyceum audiences generally came to hear famous speakers, Nast was different; the public wished above all to watch him draw. A typical reaction came from Alexander Graham Bell, who witnessed Nast’s act in October and described the performance in a letter to his parents: “He did not speak much but illustrated his subject by actually creating Caricature before our eyes. A large square frame about seven feet high, containing enormous sheets of paper, was placed, like a black-board on the platform. He would slash away at this with coloured crayons—as rapidly as if he were whipping an animal—and in little more than a minute would produce a wonderfully perfect life-size caricature of some well-known man. His power with the crayon was perfectly astonishing.”[95] A rare surviving drawing from Nast’s tour, now in the National Portrait Gallery, mocks the former president, Andrew Johnson, for tyrannical tendencies (fig. 13).[96]

After finishing his theatrical run in Cincinnati, Collodion returned to Manhattan, where he probably encountered advertisements announcing Nast’s upcoming, sold-out performances at Steinway Hall.[97] Collodion considered establishing a studio, both to make comical portraits and to train other caricaturists, but amid the depressed economic conditions following the Panic of 1873, the timing likely seemed inopportune.[98] Thus, Collodion and his wife secured a dockside booking aboard the large steamship Ville du Havre bound for France, which set to sea on November 15—and never reached land. After one week on the ocean, at two in the morning on November 22, the Ville du Havre collided with the Scottish clipper Loch Earn in one of the worst naval disasters of the nineteenth century (fig. 14). Newspapers across the globe described the horrific incident, based on the accounts of survivors. “When the crash came, in the darkness of the night, it broke clear through one side of the steamer, killing passengers in their berths, and bringing with it a deluge of water that rapidly filled the hold,” explained Harper’s Weekly. “The deck was soon thronged with startled passengers; but many, paralyzed with terror, remained in their state-rooms and perished without making an effort to escape their too certain doom. Thirty or forty passengers succeeded in getting into the long-boat and were ready for launching when suddenly the mizzen-mast fell over and crushed many of them to death.”[99] Most of the 313 passengers and crew perished in the cold, North Atlantic waters, including both Mr. and Mrs. Collodion, Victor and Françoise Malfait. The newlyweds had been married less than four months. Fewer than eleven months had elapsed since Collodion’s London debut had launched his whirlwind success. He was thirty-one. She was twenty-six.[100]

Collodion was gone, but lightning caricature continued to flourish as Nast and Régamey toured the United States, both drawing large crowds (fig. 15).[101] When the popular English comedian William Horace Lingard, famous for his celebrity impersonations, toured the United States that winter, his act included both an homage to Collodion and an imitation of Nast.[102] Nast earned a windfall from his heavily booked lecture tour, garnering the second-highest advanced ticket sales that season among the dozens of lecturers on the premier lyceum circuit run by James Redpath.[103] Touting the success of their prominent artist, Harper’s Weekly published a full-page illustration of the season’s “Popular Lecturers,” conspicuously featuring Nast in the front ranks beside his friend Mark Twain (fig. 16). Nast disliked the wearisome experience of lyceum touring, crisscrossing the United States on a relentless travel schedule calculated to maximize performances and ticket sales. After earning far more than he or Redpath had expected, and greatly missing his family, Nast abruptly ended his tour several weeks early and returned to his home in Morristown, New Jersey. Though cajoled by Redpath and others to return to the lecture stage, he declined for over a decade. However, after a series of ill-fated investments left him badly strapped for cash, Nast returned to the lyceum circuit in the late 1880s (figs. 17, 18).[104]

Just as in the United States, talented successors to Collodion had already emerged back in Britain by the time of his death. Building on the positive reception of a newly honed routine performed in Blackpool and other venues in the fall of 1873, Signor Kalulu began touring England, performing “in the manner” of Collodion, making rapid caricatures of celebrities “five times the size of life.”[105] At first, Kalulu acknowledged his obvious debt by advertising himself as “the Eminent Caricaturist, a la Collodion.”[106] However, Collodion’s fleeting career soon began fading from memory, supplanted by other caricaturists and cartoonists, who often added unique twists to the novel routine he had first popularized. By 1877, a reviewer in Derbyshire described sketches by a new lightning artist as “drawn à la Kalulu” rather than à la Collodion.[107] Gaining further notice from caricatures appearing regularly in The Hornet magazine, Kalulu had become the new touchstone for English lightning artistry.[108] Kalulu was the only stage caricaturist mentioned in the 1876 edition of The Era Almanack stage directory, but by then he already faced competition.[109] By January 1875, Tom Merry was performing in a London variety theater.[110] Another prolific lightning artist, “the Express Cartoonist, Edgar Austin,” was appearing at the Bow Music Hall in London by February 1877.[111]

Within just a few years, the professional calling of the lightning artist had become familiar even in rural areas, such as small towns in the western United States, as demonstrated by the peculiar case of Eugene Lippincott. An itinerant “lightning-sketch artist,” Lippincott traveled in the summer of 1878 on foot through California from Vallejo to Crescent City, where he was mistakenly apprehended under suspicion of murder. Newspapers reported that, after he was escorted by sheriffs to San Francisco, “in proof of his artistic ability, he has, within the brief period of his incarceration in the City Prison, ornamented the walls of his cell with a well-executed full-length sketch of a burlesque actress of a most pronounced type.” Luckily for him, after further scrutiny, Lippincott’s height, long mustache, and absence of scars on his nose helped establish his innocence.[112]

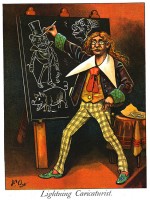

By 1885, Frederick Burr Opper’s illustrated book of children’s poems, A Museum of Wonders, included the lightning caricaturist among the categories of typical dime-museum entertainers, such as the magician, sharpshooter, silhouette cutter, ventriloquist, learned pig, phrenologist, and others (fig. 19).[113] With no need for scenery or complex staging, lightning artists easily adapted to any performance space. Thus, along with all manner of dancers, singers, illusionists, musicians, comedians, contortionists, acrobats, puppeteers, animal trainers, and so forth, the lightning artist became a fixture of the sideshow, circus tent, minstrel troupe, cabaret club, and, above all, variety theatre. By the turn of the century, over one hundred performers continued along the trail Collodion had blazed, on both sides of the Atlantic.[114]

Photographic Memories

The breakout success of lightning caricature in the 1870s relied on the visual mass culture established the previous decade with the abrupt proliferation of cartes de visite. Forerunners to various trading cards and other photographic collectibles, cartes de visite offered small images mounted on cardstock, enabling the first affordable mass distribution of photographs, especially portrait likenesses. Patented in 1854, cartes de visite rocketed to popularity around 1859 in Paris and soon caught on in London, New York, and other cities.[115]

Andrew Wynter, a prominent Victorian physician and cultural critic, described what he termed “the carte de visite mania” or “rage.”[116] An extensive market, he noted, “has sprung up with amazing rapidity,” with inexpensive photographic likenesses suddenly saturating the public sphere. “Wherever in our fashionable streets we see a crowd congregated before a shop window, there for certain a like number of notabilities are staring back at the crowd in the shape of cartes de visite.” Despite such urban spectacles, the vast scale of this novel pictorial business was not immediately obvious. “The public are little aware of the enormous sale of the cartes de visite of celebrated persons. An order will be given by a wholesale house for 10,000 of one individual.” Highly sought-after images circulated in far greater quantities. “Her Majesty’s portraits, which Mr. Mayall alone has taken, sell by the 100,000.” In sum, the abrupt “universality of the carte de visite portrait has had the effect of making the public thoroughly acquainted with all its remarkable men,” so far as appearances went.[117]

In several important ways, cartes de visite differed from the slightly earlier mass visual culture supplied by pictorial reportage in the illustrated press. Newspaper images, sometimes adapted from photographs but necessarily reproduced as woodblock engravings or lithographs, could be clipped and pasted into scrapbooks. Cartes de visite, on the other hand, offered true photographic prints, manufactured with standard dimensions and printed on high-quality paper, that were marketed expressly for inclusion within albums designed for their careful arrangement and display. Unlike ephemeral newspaper imagery, cartes de visite were meant to be collected, savored, studied, and rearranged.

Neuroscientific research has demonstrated the impressive capacity of the human brain for facial recognition, but such abilities were already intuited in the nineteenth century as viewers pored over portrait photographs. “Even the cartes de visite of comparatively unknown persons so completely picture their appearance, that when we meet the originals we seem to have some acquaintance with them. ‘I know that face, somehow,’ is the instinctive cogitation,” wrote Wynter.[118] Lightning caricature, initially the most common form of lightning artistry, profoundly relied on these new pictorial reservoirs of portraiture kept in mind by a visually sophisticated public thoroughly steeped in celebrity imagery. Though some intrepid lightning artists—including Collodion and Kalulu—sometimes caricatured audience members off the cuff, routines commonly featured only famous faces.[119] Quickly communicating a recognizable likeness with the fewest strokes possible hinged on the audience’s familiarity with specific widely circulated portraits. Although embellished with theatrical showmanship, both athletic and illusionistic, as a popular phenomenon lightning caricature constituted an encounter with the newly experienced condition of a mass visual culture consisting of cheap, widespread, iconic photographic portraiture.

Amid the flood of cartes de visite, reporters often referenced these widely circulating likenesses as a convenient shortcut past written descriptions, thereby also offering readers, still growing accustomed to torrents of photographic portraiture, reassurance about their visual credibility. For a public fascinated with physiognomy to the point of seeking character traits through the phrenological analysis of physical appearances, the mechanical objectivity of photographic portraiture offered compellingly pertinent visual information, especially regarding political leaders entrusted with public affairs. Thus, in the 1860s comments about the concordance—or sometimes discrepancy—between scrutinized studio portraits of notable persons and their witnessed appearances in public became a recurring journalistic trope. For instance, after the photographer John Jabez Edwin Mayall released a portrait of Lord Derby, leader of the Conservative Party, a London correspondent who glimpsed the politician at a Horticultural Society fête vouched that he indeed looked “marvellously like Mayall’s unrivalled portrait.”[120]

In the United States, where cartes de visite became fashionable as the Civil War commenced, northern newspapermen validated photographic portraits of Union military officers, many of whom had not otherwise been before the public eye. The Washington correspondent for the Chicago Tribune assured readers that Major Anderson “looks just like his pictures” and a Wisconsin war correspondent noted that General Burnside “looks as near like his pictures as can well be.”[121] After the war, the Washington correspondent for the San Francisco Examiner described his first sighting of President Ulysses Grant, remarking, “I had a good chance to observe his personal appearance. He looks just like his photograph likenesses, and it was by having seen them that I knew it was him.”[122] Significantly, such comments assumed a reading public thoroughly familiar with specific portraits, an assumption that would not have been blithely made a decade earlier.

By 1870, with celebrity portraiture only growing more popular as the larger format of cabinet cards began supplanting cartes de visite, the prominent Cincinnati newspaper editor Murat Halstead (one of Collodion’s first caricature targets when he performed in Ohio) commented that “the question that every one now asks about a celebrity” had become, “Does he look like his photographs?”[123] Meanwhile, celebrities could feel pressure to keep their appearance in conformance with circulating images. In 1867, the author William T. Adams joked about strictly preserving his resemblance to a published portrait, praising his barber for the “perfect” maintenance of his whiskers “for the sole purpose of looking like his picture.”[124] Such visual congruency could never be taken for granted, as Halstead explained with regard to his eyewitness interactions with another world leader, Otto von Bismarck. “You might look at all the photographs of Bismarck that are to be seen, and all the engravings and prints, and then you would not know him in the street.”[125] Rather than impugning the accuracy of photographic portraiture, Halstead here called attention to the physical changes wrought by aging as opposed to the timelessness of iconic likenesses that could persist in both the image marketplace and the public memory.

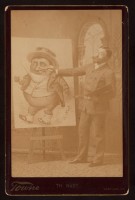

The profound reliance of lightning caricaturists on such commercial portraiture arose explicitly in a Pall Mall Gazette reporter’s interview with “Little Erskine,” already a noted lightning caricaturist at the tender age of ten. “Could you make a likeness of me?,” the journalist inquired, while visiting Erskine Williams at home. “Yes, I think so. But I’d rather make it from a photograph,” the young artist tellingly replied. Erskine’s mother then interjected “that up to the present he had not had much practice at drawing from nature.”[126] Erskine’s diary corroborates that he sought out portrait photographs of local subjects when performing in new cities.[127] A surviving Viennese cabinet card shows Erskine, proudly festooned with medals received from various music-hall managers, standing beside his stepstool and easel, which displays a sketch of the playwright Henrik Ibsen corresponding to a contemporaneous studio portrait by Julius Cornelius Schaarwächter (figs. 20, 21).[128]

A 1910 instruction manual for budding lightning artists underscored the central role of photography in crafting recognizable caricatures. Step one required directly converting a familiar photograph into a painstakingly simplified design: “Let the young cartoonist first procure a pronouncedly good photograph, in profile preferably, and copy this in detail, gradually omitting half tones or shadings until the likeness is apparent when only the minimum of strokes is used.” Step two involved rote practice to develop muscle memory for the sketch through repetition. The instructions recommended that “the outlines should be drawn again and again until the hand has become so accustomed to the correct presentation of the portrait that it can draw it off in a second or two.”[129] Having initially trained as a photographer, Collodion too apparently derived his lightning caricatures directly from photographs, as one friend recalled. “It was not caricature, but simple magnification; he would take a photograph, amplify it, and that would be it.”[130]

Not surprisingly, some caricaturists amassed large collections of celebrity portraits. Thomas Nast’s studio contained a vast and growing assortment, as the Evening Post described just before the artist’s 1873 lyceum tour. “A cabinet contains the photographs of nearly every important personage in this country and abroad,” noted the reporter, adding that Nast used an index to find specific portraits quickly from among thousands.[131] The previous year, Nast satirically skewered Benjamin Gratz Brown, the Democratic nominee for vice president, by repeatedly portraying him as merely a tag affixed to presidential nominee Horace Greeley’s ample coat, a comical visual conceit that implied Brown’s insignificance but that arose as a practical solution when Nast could not locate a photograph of the former Missouri senator (fig. 22).[132] Joseph Keppler, who came to prominence drawing political caricatures around the same time, kept “an astonishingly large collection of pictorial clippings” from the illustrated press.[133] Keppler’s image collection eventually filled an entire library, which he made available to his staff artists at the headquarters of his humor magazine Puck. Some caricaturists, such as Harry Furniss, disdained an overreliance on photography, but even he acknowledged that “if he has to draw a man for some special reason, and has not seen him, a photograph is, of course, the only means possible.”[134]

Conspicuous borrowings by caricaturists sometimes irked portrait photographers. In 1886, for instance, photographer Alexander Bassano threatened to sue Tom Merry for copyright infringement of the jubilee portrait of Queen Victoria, allegedly copied in Merry’s cartoon Queen Victoria’s Christmas published in the conservative humor magazine St. Stephen’s Review (figs. 23, 24). The matching crown, jewelry, sash, and dress, along with the identical pose, suggest that Merry surely did refer to the photograph—and understandably so since Bassano’s royal portrait was current and familiar. More surprising is the failure of the newspaper that reported the threatened lawsuit to notice the obvious similarity. Instead, the paper shrugged off the very idea that Merry might consult a photograph. “Considering that Mr. Merry first obtained fame as ‘lightning’ caricaturist at the Aquarium and throughout America, he is little likely to require the assistance of a photograph to enable him to sketch so well known a face as that of Her Majesty.”[135]

Even when caricaturists had no need to rely on specific photographs, adhering closely to the appearance of widespread likenesses could provide surefire visual cues for viewers. Perusing the illustrated satires of Merry, Nast, Keppler, and other contemporary political caricaturists reveals their frequent reliance on mass-circulated portraiture. For example, in the same cartoon that Bassano decried, Merry also presented the deceased prime minister Benjamin Disraeli as a ghostly presence by adapting an iconic cabinet card circulated by Mayall around 1868 (fig. 25).[136] By carefully altering photographic portraits and integrating them into imagined scenes, direct borrowing could easily go unnoticed by the general public. Yet, when viewing many of the same subjects in rapid succession, as happened with a traveling magic-lantern show of sixty caricatures by Merry from St. Stephen’s Review, audiences sometimes detected the repetition of facial imagery. “We get the same faces on different bodies, and in different attire in every picture,” noted one writer for the Islington Gazette.[137] However, even as lightning artists drew imitations of specific photographs, during their fast-paced stage routines most viewers probably failed to perceive the correspondence, especially since the hastily scrawled imagery from the hand of an artist seemed far removed from the detailed and mechanical perfection of the camera.

The extent to which Merry actively participated in the planning, production, and performance of the magic-lantern amusements built around his St. Stephen’s Review cartoons is unclear. However, whether deliberately or serendipitously, by 1895 his drawings again became involved with novel entertainment formats rooted in new technologies of vision, namely the peephole kinetoscope and then motion pictures projected on screens. In this way, Merry became perhaps the first, if not the most influential or prolific, of several professional lightning artists to contribute to the early experimental phase of cinema and animation. More than this, even if his participation was solely limited to appearing in several short reels, this alone has established him in the annals of British cinema as the earliest performer familiar to the general public to appear in motion pictures, thereby earning him the description as Britain’s first “film star.”[138] Further, his lightning-caricature films are routinely taken as the first known instances of British animation, though only several seconds from the end of one of his performances is known to survive (figs. 26, 27).[139]

Lightning Caught on Film

When Merry recorded his first known lightning-artist films in 1895, his finances had recently hit rock bottom. He had owned a one-third share of a theatrical trade paper, The Music Hall and Theatre Review, but it was sold at a loss in 1892.[140] His steady employment with St. Stephen’s Review came to a halt when that journal, after first attempting to reinvent itself under the title Big Ben, ceased publication in 1893. Making matters worse, these setbacks coincided with the last cyclical fluctuation of the so-called “long depression” of the late nineteenth century in Britain, with an economic boom in 1890 quickly descending into a financial recession in 1893.[141]

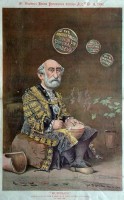

The success of St. Stephen’s Review abruptly turned to failing fortunes, costing Merry dearly in the process. According to its editor, William Allison, the parliamentary general election of 1886 “brought St. Stephen’s Review to the zenith of its prosperity.”[142] While the magazine routinely sold over 10,000 copies per week, the business for its weekly color-lithograph cartoons, which sold more copies separately than with the journal, reached far vaster circulations. The cartoons sometimes “went by hundreds of thousands. Tom Merry could not print them fast enough, and other lithograph firms had to assist.”[143] Unexpectedly, however, in 1890 the magazine fell into a quarrel with the newly formed Hansard Publishing Union, a company that controlled much of London’s printing and papermaking trades. A minor squabble escalated through threats and lawsuits, with formal allegations of libel eventually leveled against both sides. Merry’s cartoon Bubbles (fig. 28), a punning parody of a famous Pears Soap advertisement that reproduced a painting by John Everett Millais, comes from the early phase of this quarrel. It depicts the Lord Mayor of London blowing financial bubbles rather than soap bubbles—that is, creating overpriced stock assets, the largest of which is labeled “Hansard Publishing Union.” With each party feeling unfairly aggrieved, both continued along an escalating “warpath,” with the unnecessary conflict eventually leading to mutual destruction. The magazine undermined public trust in the publishing combine, while the publishers successfully pressured booksellers across London to boycott the magazine. Both went bankrupt, as did Merry, who was owed £320, presumably for unpaid printing bills, by the magazine when it folded. After personal loans ran dry and his liabilities caught up to him, Merry spent time in debtors’ prison in 1895, appeared in bankruptcy court in 1896, and died in 1902 before turning fifty.[144]

After these financial reversals with his publishing concerns, Merry returned to treading the boards with his lightning-caricature routine in an attempt to find gainful employment—and this, in turn, led to his involvement with early motion pictures. At some point in 1895, Merry recorded two short films for Birt Acres and R. W. Paul, leading innovators of the motion-picture industry in Britain who briefly worked in partnership. These two films, showing Merry making lightning sketches of German leaders Kaiser Wilhelm II (fig. 27) and Otto von Bismarck, were created for display in peephole viewers akin to the kinetoscope devices manufactured by Thomas Edison.[145] But both films were subsequently included in Paul’s watershed screening of projected motion pictures in March 1896 at the Alhambra Theatre—the same venue, though rebuilt after a fire, where Collodion had performed in Black Crook years earlier. After dissolving his business with Paul, in 1896 Acres recorded two additional short films of Merry making lightning caricatures of the British prime ministers William Gladstone and Lord Salisbury.[146] These two films were projected by Acres at Marlborough House in July 1896 as part of his royal-command film presentation.[147] Thus, short films of Merry appeared in both of the landmark screenings of early motion pictures in Britain.

With snappy, topical, and visually intriguing routines at the ready, lightning artists offered ideal content for early cinematic entertainment. Accustomed to making images visible to large audiences, their work translated easily and legibly to film. In addition, their performances had qualities nicely suited to the technical limitations of primitive motion-picture cameras. For instance, lightning artists created high-contrast images, generally working either with black ink or charcoal on light paper or with white chalk on dark slate, thereby allowing maximum clarity in photographic exposures. While their routines involved motion, activity tended to stay within neatly bounded areas, simplifying the placement of lone stationary cameras. In addition, lightning artists typically remained quite near the plane of their drawing surfaces, thereby dispensing with any need to change focus on camera lenses. At least one early film of a lightning-artist performance, seemingly a music-hall routine staged for the camera around 1900, survives in the British Pathé collection (vid. 1).[148]

Though there is no evidence that Merry participated in filmmaking beyond performing for the camera, in exactly these years other professional lightning artists began creating motion pictures.[149] In New York, the English expat J. Stuart Blackton, who performed as a lightning artist under the stage moniker “The Komikal Kartoonist,” was filmed at Edison’s studio in 1896 making a lightning caricature of the famous inventor. Soon thereafter, struck by the potential of the new medium, along with his friend and fellow performer, the stage magician Albert E. Smith, Blackton founded Vitagraph Studios, which grew into a leading producer of movies of the silent era.[150] Going beyond simple footage of his lightning-artist routine, in The Enchanted Drawing from 1900 (vid. 2), an early trick film made in the United States, Blackton appears as a lightning artist whose hastily depicted objects—a bottle, wineglass, hat, and cigar—have the added special effect of jumping off his tablet into three-dimensional space through the use of stop-motion substitution, a technique he and Smith frequently employed and even contemplated trying to patent.[151]

Also in 1896, the French pioneer of trick films, Georges Méliès, began his film studio in Paris (purchasing his first camera equipment from Paul) and immediately adapted lightning artistry into his cinematic repertoire.[152] Among the short films made during his first season, Méliès recorded at least four short lightning-sketch reels that he called Dessinateurs (Drawings), all now presumed lost, in which an artist—probably Méliès himself—drew caricatures at high speed. His subjects included the former German chancellor Otto von Bismarck, as Merry had done the year before, along with two English subjects, Queen Victoria and the politician Joseph Chamberlain. But the very first of Méliès’s lightning sketches depicted Adolphe Thiers. Given that Thiers had died nearly two decades earlier and was thus a decidedly less topical selection than the other three, it is tempting to interpret this choice of subject as a conscious homage, or perhaps an unintentional echo, referring to the controversial lightning sketch drawn by Collodion at the Alcazar in 1872. At that time, news of Collodion’s provocative act might even have reached Méliès, who was then nearly eleven, living in Paris, and already fascinated by drawing and stage mechanics.[153] Though only written descriptions of Méliès’s 1896 Dessinateurs survive, later films in which he utilized lightning artistry do exist, such as La Roi du maquillage (The Untamable Whiskers) from 1904, in which Méliès rapidly draws various hirsute portraits, transforming himself into approximations of each using makeup and long dissolves (vid. 3).

Meanwhile, in London in 1899, Paul hired the lightning artist and ventriloquist Walter Booth, an underappreciated figure in cinematic history, to create films for his production company. Booth surely acquired familiarity with motion pictures while performing as a lightning artist during intervals between short film screenings, called “Animated Photographs,” with the magician David Devant’s touring company as early as 1897.[154] Taking a keen interest in the new motion-picture technology, Booth produced trick films, like Méliès, by adapting illusionistic stage procedures to the screen. Among the tools at his disposal were his lightning-artist skills, which appear, combined with other special effects, in such works as Artistic Creation from 1901 (vid. 4). In a comical riff on the Pygmalion myth, Booth, dressed as Pierrot in a black gown and skullcap, separately sketches parts of a fashionably attired woman, assembling these components into a living character on an adjacent table. In another innovative example of early special effects, The Hand of the Artist (1906), Booth uses both still and moving photographic imagery as though it were physically malleable in ways similar to the lightning artist’s deft handling of drawing materials (vid. 5). The eponymous hand tears and crumples a photographic print of a dancing couple only for the pair to rejuvenate as miniature music-hall performers atop a wooden shelf, like a diminutive stage held in place by the artist’s hand. Without recourse to drawing, the hand still dominates the scene, supporting the stage and controlling the fate of the Lilliputian characters.

First developed by Collodion in the early 1870s, the visual idiom and performative mode of lightning artistry provided a crucial signifier for many pioneering animated films. Establishing shots of lightning artists standing beside their drawing surfaces or close-ups showing merely their hands recur frequently in early animation, with the active presence of the artist affording a key conceptual framework. Even when shown briefly at the outset of a film, the figure of the lightning artist prepared audiences for the illusion of movement, the fast-paced blend of the comedic and the uncanny, and the mysteries of visual transformations that viewers associated with lightning-artist routines. Notably, the two films perhaps most often identified as origin points for full-fledged animation utilize such devices. Drawn by Émile Cohl, another caricaturist from the circle of André Gill, Fantasmagorie (1908) begins with the hand of the artist drawing a simple figure, who proceeds to move after the hand departs (vid. 6). In his film Little Nemo (1911), Winsor McCay, who performed as a vaudeville lightning artist starting in 1906, includes several sequences of himself drawing his familiar cartoon characters on paper. Moreover, the animated protagonist, Little Nemo, himself steps into the role of lightning artist at the end of the film, summoning his friend, the Princess of Slumberland, into existence by drawing her (vid. 7).[155]

The emergence of animation as a familiar cinematic category might even be construed as the gradual process of veiling the generative figure of the lightning artist while keeping the artist’s drawings visible, a process requiring both technical innovations to hide the artist’s physical presence and the acclimation of audiences to new modes of viewership that no longer retained visual traces of the means by which images were created or manipulated. Just as Collodion, the progenitor of lightning artistry, had vanished yet left behind him a new performance genre, so too the disappearance of the lightning artists of the early cinematic era marked the onset of the novel medium of animation.

All translations are by the author, who gratefully acknowledges Matt Bailey, Scott Carpenter, Perry Chapman, Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, Malcolm Cook, Fred Hagstrom, Nicholas Jones, Cara Jordan, Alison Kettering, David Lefkowitz, Patricia Mainardi, Susannah Shmurak, and Isabel Taube for their thoughtful assistance, insights, and suggestions pertaining to this research.

[1] Sometimes the phrase “lightning artist” was also used to describe quick-change performers (comedians who mimicked the appearance of different public figures with comically abrupt costume changes), but more often such performers were called “lightning-change artists.”

[2] Charles L. Bartholomew, Chalk Talk and Crayon Presentations (Chicago: Frederick J. Drake & Co., 1922), 24–25. Bartholomew was a lightning artist himself, based in Minneapolis, performing under the stage name Bart. See, for example, “Gossip of the Town,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, October 23, 1911, 5.

[3] Donald Crafton, Before Mickey: The Animated Film 1898–1928, rev. ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 48–57. Crafton’s more recent work, such as Shadow of a Mouse: Performance, Belief, and World-Making in Animation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), exemplifies the more thoroughgoing application of performance studies to animation history, as do books such as Malcolm Cook, Early British Animation: From Page and Stage to Cinema Screen (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International, 2018); and Nicholas Sammond, Birth of an Industry: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Rise of American Animation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015). These explorations of performance studies within film history offer one example of the move toward greater “intermedial” analysis of early cinema, as called for by Lynda Nead in her influential study The Haunted Gallery. See Lynda Nead, The Haunted Gallery: Painting, Photography, Film c. 1900 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007), 2.

[4] Scott Curtis, “The Silent Screen, 1895–1928,” in Animation, ed. Scott Curtis (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2019), 20; Annabelle Honess Roe, “Animation and Performance,” in The Animation Studies Reader, ed. Nichola Dobson, Annabelle Honess Roe, Amy Ratelle, and Caroline Ruddell (New York: Bloomsbury, 2019), 70.

[5] Another common assertion is that lightning artistry derived from amateur parlor amusements, developing from such intimate gatherings to publicly staged entertainments. However, the opposite would seem to be the case. Discussions of such parlor amusements seem to postdate the 1870s. For example, one 1910 handbook describes lightning sketching as a “novel” type of parlor amusement. See Cecil H. Bullivant, Home Fun (New York: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1910), chapter 33 on “Lightning Cartoons and ‘Fake’ Sketching.”

[6] Cook, Early British Animation, 67.

[7] Advertisement for “Crane’s Lyceum Entertainments,” Daily Freeman (Kingston, NY), November 7, 1873, 2.

[8] In Europe, early modern depictions of artists at work typically do not position them on display for visitors, suggesting that artists perhaps wanted to guard technical secrets and maintain professional etiquette. For instance, the iconic engraving showing the imagined invention of oil painting in the studio of Jan van Eyck, as later drawn by Stradanus and engraved by Jan Collaert around 1600 for the series Nova Reperta, carefully places a portrait sitter and her companion so that they cannot view the nearby artists at work. Exceptions to this rule seem to have more to do with placing artists in allegorical settings, such as Gustave Courbet’s The Artist’s Studio from 1854–55, or amid illustrious company, as with Francisco Goya’s The Family of the Infante Don Luis from 1783–84.

[9] “Personal,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (New York), December 28, 1861, 94. Given the continuation of the Civil War, it is not surprising that his announced lecture seems not to have occurred.

[10] His birth certificate is in the Registre des naissances de 1842, acte no. 1077, Archives Départementales du Nord, État Civil de Lille, Lille, France. His parents, also listed on his marriage certificate, were Alexandre-Victor Malfait and Appoline-Albertine-Joseph Bocquet. His marriage license from July 26, 1873, in Paris corroborates his identity as a professional artist, aged thirty-one, born in Lille.

[11] “le pseudonyme de Collodion, qu’il avait emprunté à son métier de photographe.” See “Dépèches télégraphiques,” La République française (Paris), December 6, 1873, 2 (col. 2).

[12] “Collodion . . . était apprenti photographe à Clermont en Auvergne.” “Chronique,” Le Siècle (Paris), December 11, 1873, 2.

[13] “Quelque temps avant la guerre, cet artiste a passé trois ou quatre mois dans notre ville. Il venait de Paris où la photographie ne semblait pas l’avoir enrichi.” “Chronique Locale,” Mémorial de la Loire et de la Haute-Loire (Saint-Étienne), December 7, 1873, 2.

[14] Collodion is made by dissolving gun cotton (nitrocellulose) in ether. It has been utilized in many manufactured products, ranging from cosmetics to electronics to explosives. Used by the medical community as an adhesive varnish to cover cuts and wounds by 1848, it became most familiar to the public for its photographic applications. Its innovative use in glass-plate photography was discovered by Frederick Scott Archer, who published his results in 1851.

[15] “Plusieurs mois après, il vint à Clermont-Ferrand, où se trouvait installé un jeune et charmant artiste caricaturiste, de ses amis, nommé Malfait, mais qui se faisait appeler Collodion, sans doute pour mieux faire comprendre au public avec quelle instantanéité il prenait la ressemblance d’un portrait et avec quelle promptitude il le reproduisait.” Job-Lazare [Émile Kuhn], Albert Glatigny: Sa vie, son oeuvre (Paris: A. H. Bécus, 1878), 63. Presumably, Kuhn was friends with Collodion since, on page 134 of the Glatigny biography, Kuhn quotes a letter in which Glatigny says that Collodion mentioned when Kuhn would be arriving in Paris. Glatigny worked with Collodion as a contributor to La Mouche; “Chronique Locale,” Mémorial de la Loire et de la Haute-Loire, July 4, 1867, 2.

[16] Charles Budant, a singer who befriended Collodion during the artist’s stay of several months in Vichy in 1869, explained the pseudonym similarly, recollecting how the artist “had made himself known under the pseudonym Collodion. Photography was slower than his pencil, and the clearest mirror was less faithful than the portraits that abounded under his fingers in the days of inspiration.” See Charles Budant, “Correspondance,” La Comédie, Journal Illustré (Paris), December 21, 1873, 3. “J’ai vainement cherché dans plusieurs journaux un souvenir à la mémoire de ce grand brave garçon qui s’était fait connaître sous le pseudonyme de Collodion. La photographie est moins rapide que ne l’était son crayon, et le miroir le plus pur, moins fidèle que les portraits qui foisonnaient sous ses doigts aux jours d’inspiration.”

[17] About the École Lyrique, see Charles Hervey, The Theatres of Paris (London, 1847), 3–4; and The Diamond Guide for the Stranger in Paris (London: Hachette & Co., 1870), 210.

[18] “les billets sont vendus le plus cher possible aux amis et connaissances, et la représentation a lieu, hilarante et burlesque au possible, devant un public enthousiasmé.” . . . “A toutes les tables, en un mot, on cause théâtre, et, dans un coin, le caricaturiste Victor Collodion fait la charge de ses voisins.” (Italics in original.) [Félix Savard], Les Petits mystères de l’école lyrique (Paris, 1862), 42–44.

[19] Regarding La Mi-Carême, see the 1863 printed program titled La Mi-Carême. Adieux au carnival de 1863 (Mid-Lent. Farewell to the carnival of 1863) in the collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris. The song anthology is entitled Chansonnettes nouvelles de Victor Collodion (New ditties by Victor Collodion); Victor Collodion, Chansonnettes nouvelles de Victor Collodion (Mâcon: Legrand, 1865). Also, in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Départment Musique, there survives sheet music for at least one song, “Allez vous couchez” (Go to bed), published in Paris in 1866, with lyrics by Collodion and music by Marc Joly, sung by Léon Bertrand, that notes it was performed at the Pavillon de l’Horloge, an epicenter of the Parisian chanson culture. The Pavillion de l’Horloge and the Alcazar d’Hiver, where Collodion performed in 1872, as described later in this article, both appear in the list of “Principal Cafes Chantants” published in the annual theatre directory The Era Almanack, 1869, ed. Edward Ledger (London, 1869), 68.

[20] “Chronique Locale,” Mémorial de la Loire et de la Haute-Loire, May 4, 1867, 2. The paper attributes the information to the Parisian theatrical journal Le Figaro, though this source seems not to have mentioned Collodion as a director, but only Savard, who was probably better known to Parisian audiences. See “Théâtres,” Le Figaro, April 25, 1867, 4. In London, The Athenaeum mentioned a revival at the same venue two years later, attributing it to “Félix Savard and Victor Collod [sic]”; see “Musical and Dramatic Gossip,” The Athenaeum, March 27, 1869, 447. Un crime dans une valise also played at Le Théâtre-Français et le Gymnase-Dramatique de Bordeaux (in either 1869 or 1870), and in Lille (in June 1872) and, later, at the Théâtre de Tours (in June 1880). See Gaston Bastit, La Gascogne littéraire (Bordeaux, 1894), 178; Léon Lefebvre, Histoire du Théatre de Lille, vol. 4 (Lille: Lefebvre-Ducrocq, 1903), 280.

[21] “Coucher tout habillé sur un matelas par terre, dans la chambre triste, froide et déjà trop petite d’un ami pauvre,—il n’y a que ceux-là qui aient bon cœur et vous recueillent;—déjeuner d’un sou de lait, dîner d’une croûte.” “Chronique,” Le Siècle, 2.

[22] In France, the word “vaudeville” referred to a whimsical, often brief, comical performance with music. In the United States, the term came to define the popular theatrical genre of variety shows featuring all manner of different entertainers. Le Parapluie de Monriflard (The umbrella of Monriflard) and Le Frotteur (The rubbing) were produced at Le Théâtre-Français et le Gymnase-Dramatique de Bordeaux in 1869 and 1870. La Grande dépêche (The great dispatch), a review created in collaboration with a citizen of Nantes named Bureau, appeared at the Théâtre de la Renaissance in Nantes in April 1871; see Etienne Destranges, Le Théâtre à Nantes (Nantes: Jules Lessard, 1902), 314; and “Chronique Locale,” La Gironde (Bordeaux), June 10, 1871, 3. Another review, Le Mans, 10 minutes d’arrêt! (Le Mans: ten-minute break!), debuted at Le Théatre du Mans on November 7, 1871; see surviving program with detailed synopsis in the collection of the Royal Library of Belgium and “Départements,” Le Petit Journal (Paris), January 27, 1872, 4. A revue by Collodion called Rabelais was announced for Poitiers in early 1872, and another for Tours called Tours à vol d’oiseau (Tours as the crow flies); see “Départements,” 4; “Gazette de Paris,” Phare de la Loire (Nantes), January 27, 1872, 3 (col. 2). In addition, a manuscript by Collodion for an apparently unproduced short play with the intriguing title Un photographe somnambule: Folie militaire en un acte (A somnambulist photographer: Military madness in one act) sold at auction in Paris in 2014.

[23] “Il promenait son crayon de café en café, faisant des portraits à la minute.” “Chronique Locale,” Mémorial de la Loire et de la Haute-Loire, December 7, 1873, 2.

[24] “Chronique Locale,” Mémorial de la Loire et de la Haute-Loire, July 16, 1866, 2.

[25] Budant, “Correspondance,” 3. “A Vichy, ayant pour tout équipage son éternel habit de velours noir, son grand chapeau en éteignoir, des crayons Conté dans toutes ses poches, il allait, abrité sous un parasol doublé de rose, dans l’un des cafés où il avait laissé en dépôt un rouleau de papier teinté, voir ‘si un bonhomme voulait se faire portraicturer [sic].’ . . . Tout le monde se rappellera l’avoir vu sous son brillant costume style Charles IX.” (Italics in original.) The outdated spelling of “portraicturer” is deliberately archaic for comic effect.

[26] The studio was located at 57 rue de la Porte-Dijeaux, a short walk from the office of the journal Le Gaulois, to which Collodion contributed, at 61 rue Saint-Sernin. See “Chronique Locale,” La Gironde, December 20, 1868, 2.

[27] For comments on the practice of depicting big heads on small bodies in French caricature of the nineteenth century (“la formule de la grosse tête sur un petit corps”), see Bertrand Tillier, La Républicature: La Caricature politique en France, 1870–1914 (Paris: CNRS Éditions, 1997).