The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

|

Siegfried Bing's Salon de L'Art Nouveau and the Dutch Gallery Arts and Crafts |

|||||

|

On the 11th of August 1898 a Dutch gallery opened in The Hague under the English name Arts and Crafts (fig. 1). This was less than three years after Siegfried Bing had transformed his shop in Paris into the new and prestigious Salon de L'Art Nouveau. Important artist-designers in the Netherlands immediately recognized Arts and Crafts as the first Dutch gallery for contemporary decorative arts. The gallery presented handcrafted furniture, textiles, ceramics and metalwork of high quality alongside paintings and sculptures. Arts and Crafts only lasted until July 1904, whereas Bing's gallery closed in March 1905. But during the six years of its existence, the gallery played an important role in the world of Dutch applied arts by showing works by Dutch and foreign modern designers and by stimulating debate about the path the Dutch revival of the applied arts should take. This debate, which pitted nationalism against internationalism, led to the creation, in 1900, of another gallery called 't Binnenhuis.1 Located in Amsterdam, it promoted modern design referring to a Dutch national style rather than inspired by foreign models. 't Binnenhuis would outlast Arts and Crafts by twenty-two years. | |||||

| In this paper I will discuss similarities and differences between the Arts and Crafts gallery and Bing's Salon de L'Art Nouveau. In so doing, I will point out the importance of the batik technique to women's involvement with Arts and Crafts, and I will focus on the discussion of nationalism in design in a European context. | ||||||

| L'Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts The Salon Arts and Crafts, as the gallery was called by the German magazine Dekorative Kunst in 1899, had many similarities to Bing's Salon de L'Art Nouveau.2 In both galleries, the Belgian artist and designer Henry van de Velde (1863-1957) played an important role right from the start. Van de Velde, a key figure in several overlapping circles of artists and art lovers in Brussels, Krefeld, Hagen, The Hague and Paris, had many friends; among them was the Dutch artist Johan Thorn Prikker (1868-1932), a number of whose works had been featured in Bing's gallery at its opening.3 After studying at the Academy of Art (Academie van Beeldende Kunsten) in The Hague during the early 1880s, Thorn Prikker—like Van de Velde—had developed into a painter; he is now known as one of the early Dutch symbolists. He got to know Van de Velde at the start of the 1890s and exhibited in 1893 with the latter's influential Brussels group of artists, Les XX. But his work did not receive much praise outside artistic circles and, partly because of this, he turned to decorative art and started experimenting with batik. Some eight months before the opening of the Arts and Crafts gallery Thorn-Prikker told Van de Velde about the gallery in a letter: "Dear friend. One of my acquaintances is going to start an art business in The Hague, something in the spirit of that of Bing in Paris. In addition to a few paintings he especially wanted to show applied Arts. I told him to pay you a visit, to ask for your support, and to inquire about addresses and references for Belgian and French artists."4 |

||||||

|

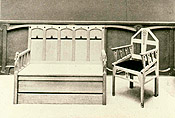

The name Arts and Crafts clearly referred to the English design reform movement of William Morris (1834-1896). On his travels through Europe, John Uiterwijk, the founder of the Arts and Crafts gallery and the friend Thorn Prikker had referred to, had seen similar galleries and workshops in England. Not much is known about the specific places he visited but according to Walter Crane, Uiterwijk worked for some time at Charles Robert Ashbee's The Guild of Handicraft.5 The Arts and Crafts gallery's financial backer was Chris Wegerif (1859-1920), a relative of Uiterwijk, who had an architecture and construction firm in Apeldoorn, a wealthy town with a residential character (and a 17th century palace of the royal family) in the east of the Netherlands. Around 1895, he had become interested in the latest developments in architecture and the decorative arts. He turned his Apeldoorn house into a meeting place where artists shared ideas about good art and design. He also became a dealer of furniture and (through his wife) batiked fabrics. His relationship with Uiterwijk, who became his business manager, resembled the arrangement between Van de Velde and his business manager Henri Jaeger, who had left Bing to come to work for Van de Velde.6 One of the artists who visited Wegerifs house in Apeldoorn was Thorn Prikker. Shortly after Wegerif commissioned him to redesign the mantelpiece in his living room, Thorn Prikker started to design furniture for Arts and Crafts. His best-known piece for Arts and Crafts, a dining room chair, strongly resembles Van de Velde's dining room furniture in his house Bloemenwerf in Ukkel near Brussels (1895), where Thorn Prikker had stayed several times (fig. 2).7 | |||||

| At its opening the Arts and Crafts gallery presented two model rooms by Van de Velde: a dining room and a bedroom. With this arrangement the gallery followed in the footsteps of Bing's Salon de L'Art Nouveau. In Paris, Van de Velde had presented a dining room, a smoking room, and a study at the opening exhibition in 1895, and he had designed the back room of the shop and furnished it with pieces modelled on those for his house Bloemenwerf. The first Salon de L'Art Nouveau also had presented a bedroom by Maurice Denis, a waiting room by Edouard Vuillard, a circular salon by Paul-Albert Besnard—all of them French designers—and a boudoir with silk paintings by the Australian artist Charles Conder. While some of the model rooms in L'Art Nouveau were installed for only a short time, to be updated or replaced by other work, Van de Velde's three rooms seem to have been left unaltered until at least 1897, when plans for the Arts and Crafts gallery were under way. These rooms best matched the concept of unified interior design which Siegfried Bing was promoting. He favored Van de Velde's more restrained curvilinear art nouveau with abstracted suggestions of organic, growing forms over the more distinctly naturalistic floral art nouveau of the French artist-designers from Nancy. For Bing, Van de Velde exemplified a design attitude akin to British Arts and Crafts.8 Bing's admiration of British arts and crafts design was also borne out by the installation of an English model dining room in 1898, with furniture by W.A.S. Benson, and other English pieces of furniture.9 The combination of Belgian art nouveau and contributions by French artists on the one hand and British Arts and Crafts on the other might be considered a stylistic "clash". But ideologically the movements were much alike. Van de Velde, for one, was greatly inspired by William Morris. His support for Morris' socialist ideas led him to decorative arts and design as an alternative to the restricted aestheticism of painting.10 In two articles for the magazine Dekorative Kunst, from 1897 and 1903, Bing considered the English, Dutch, and Belgians as the nations that had discovered how to create a new form of decorative art.11 | ||||||

| Photographs of Van de Velde's model rooms in the Dutch Arts and Crafts gallery were published in the magazine Dekorative Kunst. They show that his rooms in The Hague were quite different from those at L'Art Nouveau (figs. 3, 4). They contained furniture with lightly curved legs and backs. A broad freeze at the top of the wall had colorful, flowing linear designs. The dining room mantelpiece had a mirror in a wooden frame, flanked on both sides by small cabinets with glass doors. The actual fireplace had built-around cupboards covered by glass mosaic with colorful and bold floral motifs. Two benches lined with copper seem to have projected slightly into the room.12 The design of the mantelpiece strongly resembled an interior which Van de Velde had created a year earlier for Léon Biart in Brussels. In 1899, the bedroom in Arts and Crafts was depicted in the catalogue for Van de Velde's company. It was made of Australian wood, with a very expensive ceiling structure and grey-green textile wall coverings. The hearth front, the opening of which was covered with two doors, was decorated with patterned tiles.13 | ||||||

| Alongside Van de Velde's rooms, the opening exhibition at Arts and Crafts featured work by many other foreign artists, which made Arts and Crafts a cosmopolitan gallery. No inventories of the exhibition survive, and only a few of the objects shown can be identified from photographs of the gallery's interior or from museum collections. But reviews and advertisements in various Dutch newspapers mention two carpets by Frank Brangwyn, who also exhibited with Bing—one of these could have been the now well-known "Japanese Vine" carpet from 1896-1897, and perhaps this was the "fine colored carpet" that art critic J.V., (probably Jan Veth), found to be the most beautiful.14 Reviews also refer to glass by the American Louis Comfort Tiffany presented in the middle of a room hung with pointillist paintings. Critic J.V. thought the Tiffany pieces were very fine examples, "shaped and colored in a marvellously delicate manner."15 According to a certain J.H.S., more glass of a different nature came from the German, Karl Köpping, and from the French firm A. Bigot & Co.,16 although the Bigot pieces were undoubtedly ceramics. There were also ceramics from the Belgium-trained Englishman Alexander Finch, who had been a member of Les XX; it seems Finch showed new pieces of ceramics in the gallery, which were described as less Japanese and "much more noble."17 Another review mentions earthenware by the French ceramicist Albert Dammouse, known for his stoneware.18 From Henry van de Velde there were, in addition to his rooms, several small items: book-covers, a pewter inkwell, and a copper door lock.19 The exhibition featured a rich choice of posters; the critic J.V. found those by Henri de Toulouse Lautrec and Théophile Steinlen to be the best. In addition, there were a few bronze sculptures by Constantin Meunier and George Minne, both highly esteemed artists, as well as drawings by Edgar Degas, Auguste Renoir (a portrait of a girl), Théo Van Rijsselberghe (nude studies), and a seascape (which may have been a painting) by Claude Monet.20 Unspecified foreign craftwork is also mentioned: copperwork and carpets or tapestries from England, Italian, Russian, and English pottery, and French reflet métallique (lusterware), ceramics and jewelry.21 Dutch crafts were best represented by the batik textiles of Johan Thorn Prikker: curtains, cushions, a folding screen and small items such as ladies bags and purses.22 The exhibition featured Dutch ceramics produced by the Rozenburg factory in The Hague, but the exact nature of the pieces is unknown. Among the Dutch painters whose works were shown at the exhibition were the newcomer J.J. Isaäcson from Amsterdam, who was represented by ten paintings with biblical and other scenes, and the more famous symbolist artist Jan Toorop, who had also exhibited with Les XX. Isaäcsons work was found to be un-Dutch and eastern, both in subject and in color; another critic found it weak.23 But all in all these first reviews were positive. | ||||||

| It would seem that most of these artifacts were presented for the opening months only. And, since most of the artists were also presented at L'Art Nouveau, perhaps some artifacts were even borrowed from Bing. The Tiffany glass, for example, was referred to in newspaper reviews as a product from New York. But since Bing was the sole representative of Tiffany in Europe at the time, it seems likely that he supplied the glass.24 Van de Velde must also have brought in artists, as he was asked to do by Thorn Prikker. | ||||||

|

The interior of the Arts and Crafts gallery resembled L'Art Nouveau, although only in terms of layout and not in design. There was a downstairs area where monumental mantelpieces and furniture were displayed. Massive stairs led to an upstairs area with more furniture and paintings (fig. 5). But the rooms at L'Art Nouveau appear to have been much larger and airier, with atrium-like galleries as seen in Parisian department stores. Chris Wegerif was responsible for the design of the interior and the staircase; Johan Thorn Prikker had designed show cases in an extravagant curvilinear style. | |||||

| Batik The similarities between the Arts and Crafts gallery and Siegfried Bing's business were not limited to the fact that they showed works by the same artists. The influence of East Asian Art was also important at both galleries. Of course, for Bing this meant Japonisme; in 1895, Thorn Prikker still referred to him as "the Japanese man in Paris."25 Long before the establishment of Arts and Crafts, the fashion for Japan had already led to contacts between Bing and the region of Leiden/The Hague.26 Bing had started his career promoting Japanese art and had brought together Japanese and some Chinese objets d'art in his first shop back in the 1870s. When Bing, in 1891, offered for sale the Japanese collection of the French art critic and japoniste Philippe Burty, at the request of Burty's widow and daughter, he also acted as agent for the important Ethnological Museum in Leiden, which had been founded in 1883. The museum had given Bing a free hand in purchasing, and he bought several pieces for its collection. After this sale the museum regularly bought art objects from Bing and became one of his more regular customers.27 In 1893 art lovers from the local Haagsche Kunstkring (Hague Art Society) in The Hague, which lies about 12 miles from Leiden, asked Bing to create an exhibition of Japanese art from his Paris shops. This exhibition opened on August 5, 1893 and subsequently travelled to Amsterdam and Rotterdam. In the 1880s Bing's magazine Le Japon Artistique, which was known in the Netherlands, presented Japan as a source of inspiration for Western fine art and applied arts.28 Schools of applied arts and art academies had copies in their libraries, and design students were encouraged to study Japanese woodcuts and textile designs and use them for design drawings. The Rozenburg ceramics factory in The Hague derived decorative designs from Japanese prints for its egg-shell porcelain, a very delicate ceramic product which was presented to great acclaim at the Parisian Exposition Universelle in 1900. Japanese items and works of art were also sold at the well-known Groote Koninklijke Bazar in The Hague which was established in 1843; even Vincent van Gogh seems to have known the Bazar for its Japanese pictures, just as he knew L'Art Nouveau and Bing for the Japanse artifacts.29 |

||||||

| The influence of Japan was very strong in the first years of the Dutch design reform movement. But the Eastern inspiration in the Netherlands was not confined to Japan. Art forms from the colonial Dutch East Indies were also influential in Dutch decorative art. This is seen most clearly in the artistic use of batik. Dutch artists first started experimenting with the technique around 1892, but until 1898 there was no workshop where batiked fabrics were produced on a large scale. This changed with the creation of the Arts and Crafts gallery's batik workshop in Apeldoorn. It was the brainchild of Agathe Wegerif-Gravestein (1867-1944), wife of the gallery's financial backer, who started the workshop to produce products for the gallery. It was one of three workshops linked to the Arts and Crafts business—another similarity to Bing's L'Art Nouveau—right from the company's creation.30 The other two included a furniture workshop in Apeldoorn and a copper workshop behind the gallery in The Hague. By starting a batik workshop, Agathe Wegerif prevented the Arts and Crafts company from being a solely male preserve. She was, in fact, one of the first female artists to consciously and explicitly take part in the reform of Dutch applied arts. Agathe Wegerif regularly wore batiked dresses which made her appear very exotic, like a chic femme fatale (fig. 6). She was worshipped by her husband, was enterprising, and emphatically took her place as a woman amidst male artists and artist-entrepreneurs. Not only did she start the batik workshop, but in 1902 she also started and led a lace-making school in Apeldoorn which moved to The Hague four years later. Around 1900 her batik workshop appears to have employed some 24 to 30 women (fig. 7).31 | ||||||

| In an undated and unpublished biographical manuscript, Agathe Wegerif later wrote that conversations with Johan Thorn Prikker made her focus on batik.32 But with her initiative in starting a batik workshop she followed in the footsteps of enterprising Dutch women in the colonies of the East Indies who had started batik workshops there as early as 1845. These workshops had grown into flourishing businesses in which Indonesian girls and women decorated textiles for the European market. These Indonesian workshops showed their batiks—whose design was a mixture of traditional Indonesian, Chinese, and European motifs33—at important exhibitions, such as the 1898 women's exhibition in The Hague, the Nationale Tentoonstelling van Vrouwenarbeid, and in 1900 at the Parisian Exposition Universelle. At the latter exhibition, the Arts and Crafts gallery also showed batiks—its first presentation outside the Netherlands. Its batik workshop showed samples of batik products and it produced textile furnishings for the Dutch pavilion. These were made after a design by the architect-designer J. Mutters, who only worked with the Arts and Crafts gallery for this occasion.34 | ||||||

| Soon after their first exhibition, Arts and Crafts batik textiles became known abroad. People were intrigued by the novelty of their technique. The designs for the batiks were initially created by Johan Thorn Prikker (fig. 8). Agathe Wegerif had his designs reproduced in her workshop in limited editions, but few have survived. Wegerif appears to have chosen the colors herself, and one critic, in an article on her batiks for the family magazine Eigen haard, thought the brightness of the colors of the silk-velvet batik textiles made one think of the delicate colors of Tiffany glass, stating they caused a "sensation of delight".35 The production was hardly commercial, since what can probably best be described as art batik always remained exclusive. Siegfried Bing must have been aware of them in late 1897-early 1898, even before the opening of the Arts and Crafts gallery, as a well-known chair by Henry van de Velde (fig. 9) that Bing sold to one of his most important customers, the director of the recently established museum for the applied arts in the Norwegian town of Trondheim, had batik upholstery. The chair was depicted in the 1899 catalogue of Van de Velde's company, but with another cover.36 Arts and Crafts batiks after Thorn Prikker's designs were also sold in Julius Meier-Graefe's Parisian gallery La Maison Moderne (fig. 10). Meier-Graefe, a young German art critic who had moved to Paris in November 1895, probably already knew Bing before he came to France. In any case he shared Bing's ideas about Salons with model rooms for the display of modern decorative arts. Both men had visited the innovative gallery La Maison d'Art in Brussels, which had opened in December 1894, as well as Van de Velde's house in Ukkel. Thorn Prikker also knew Meier-Graefe who helped the artist—who was constantly short of money—in 1897 by giving him small commissions for batiked furnishings, including a bedspread and curtains.37 Moreover, in 1900, or shortly before, Meier-Graefe also seems to have had batiks produced by the workshop after designs by Georges Lemmen and other French artists.38 This means he must have been in contact with Agathe Wegerif as well. | ||||||

| Alongside Thorn Prikker's designs, the workshop, for a short period, also produced designs by Chris Lebeau (1878-1945). Lebeau, just starting his career as a decorative artist, was to become one of the most important designers in the Netherlands. A batiked cover for Louis Couperus's novel De Stille Kracht (The Silent Force), now an icon of Dutch Art Nouveau, was the product of his collaboration with Agathe Wegerif's batik workshop (fig. 11). In stylistic terms the cover could be called expressionist avant la lettre, just like Thorn Prikker's designs. | ||||||

| Only after the two male artists Thorn Prikker and Lebeau had broken their ties with the batik workshop, which they would later criticize, did Agathe Wegerif start to produce her own designs for batiks. Captions on photographs of Arts and Crafts furniture in the German magazine Innen-Dekoration cite the names of Agathe and her husband Chris, suggesting that he designed the furniture and she the upholstered fabrics (fig. 12).39 At this time batik upholstery fabrics were her most important products. In contrast to Thorn Prikker's powerful expressionist designs, her work shows a fine, linear style, which was in keeping with the inlaid decoration of the furniture designed by her husband. Agathe Wegerif had had no professional art training and approached her designs accordingly; they were eclectic, and often made in a free, expressionistic manner. Some journalists liked them, others criticized them. But few fellow male artists took them seriously.40 | ||||||

| In the years that followed, Wegerif spread awareness of her batik work throughout Europe. In 1910 she exhibited at the Parisian Salon of the Union des Arts Décoratifs, and she would remain one of the few Dutch artists to exhibit with this organization.41 The well-known writer and bon vivant, Gabriele d'Annunzio, described the room of one of the characters in his novel Forse che si, forse che no (1910) as having Wegerif's batiks on the wall.42 The batik workshop even supplied curtains for a hotel in St. Petersburg. Her work could also be seen on exhibitions in the US: in 1915 she was awarded a gold medal for her batiks at the Panama Pacific International Exhibition in San Francisco and in 1916 another award at the Panama California Exhibition in San Diego.43 Around 1920, Wegerif would again batik designs by Chris Lebeau in a set of large wall hangings for a cinema in The Hague.44 At this time she still had the workshop, and she created so-called "fantastic" batik works: throws, and wall hangings in a symbolist-expressionist style, which she exhibited in 1917 in The Hague at the Groote Koninklijke Bazar.45 | ||||||

| The importance of Agathe Wegerif's batik workshop for the Arts and Crafts gallery cannot be underrated. It set the gallery apart from Siegfried Bing's business, which was still mainly a male affair. Bing did exhibit some work by women designers, notably leather bookbindings and, via Rookwood Pottery, ceramics decorated by women. He also organized a few exhibitions of works of women painters and sculptors and presented their works in general exhibitions. Moreover, he was assisted by a female sales agent, Marie Nordlinger, who was originally a craftswoman from one of his workshops. Because of this he has been called "something of a champion of women's rights ..."46 But, despite his championing of women, Siegfried Bing was firmly in charge of everything that went on in his gallery, and women, including Marie Nordlinger, played a subservient role. By contrast, Agathe Wegerif was an important individual presence in the Arts and Cafts gallery. Her name is hardly left out of Dutch reviews and even in foreign magazines the Arts and Crafts gallery is usually associated with both Wegerifs. | ||||||

| The "modern Belgian curvatures" were found in Van de Velde's model rooms and in the furniture designed by Johan Thorn Prikker for the Arts and Crafts gallery. Their reception—like that of the model rooms in L'Art Nouveau—was not positive; Arts and Crafts was said to be focused on Belgian and French art nouveau and criticized for its unDutch design. But Johan Thorn Prikker left Arts and Crafts in 1900; the furniture he designed in collaboration with Henry van de Velde for a villa in The Hague was produced by a new company which he formed in 1902. Soon thereafter he departed for Germany where he, like Van de Velde, became an acclaimed artist.49 There was another striking difference between L'Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts: the aspect of nationalism and rationalism. This aspect became a point of discussion among Dutch artists-designers as a result of the Arts and Crafts company's products, especially the furniture they made. One of the critics summed this up in a lecture for the Art Workers Guild in London in March 1903: "Holland first followed the example of the English; then they adopted some modern Belgian curvatures, to finally turn to modern Austrian art. No doubt, the national character will triumph in the end. The sound principles [of nationalist design] already make themselves felt in the simplicity of forms, both interior and exterior, and colors, in the use of authentic materials, in their treatment, and in the distrust of 'fashion.'"47 |

||||||

| The "modern Belgian curvatures" were found in Van de Velde's model rooms and in the furniture designed by Johan Thorn Prikker for the Arts and Crafts gallery. Their reception—like that of the model rooms in L'Art Nouveau—was not positive; Arts and Crafts was said to be focused on Belgian and French art nouveau and criticized for its unDutch design.48 But Johan Thorn Prikker left Arts and Crafts in 1900; the furniture he designed in collaboration with Henry van de Velde for a villa in The Hague was produced by a new company which he formed in 1902. Soon thereafter he departed for Germany where he, like Van de Velde, became an acclaimed artist.49 | ||||||

| The furniture designs of the Arts and Crafts company then became the responsibility of the owner Chris Wegerif. An architect-builder, trained in his father's carpentry workshop, Wegerif appears to have had just as much aptitude for furniture designing as the artist-designers Van de Velde and Thorn Prikker. Moreover, he was close to the production process as the furniture he designed was made in his carpentry workshop in Apeldoorn. The company's first and only sales brochure from 1901 exemplifies the start of this artistic take-over. Dutch and English versions of the booklet were published, and the manager John Uiterwijk was probably responsible for the contents.50 At the same time, a brief article about the Arts and Crafts batiks appeared in The Studio.51 In fact it is only from this time that a relatively large collection of furniture can be documented, although mainly through contemporary photographs in magazines and in a rare, clearly unofficial photo album.52 | ||||||

| Although some of Wegerif's earliest pieces of furniture still are reminiscent of the works of Van de Velde and Thorn Prikker, it is clear that before long he became more interested in British, German, and Austrian design than in French and Belgian design models. The stylistic "split" we see in his earliest works reflects the clash of styles seen in the furniture in Bing's L'Art Nouveau. There is no indication of Wegerif's precise sources, but if one reviews major design magazines, particularly Dekorative Kunst and Innen-Dekoration, there is little doubt as to his sources of inspiration. Most of his furniture bears a strong resemblance to the work of either Scottish and British architect-designers such as Charles F.A. Voysey, Charles Robert Ashbee, and Charles Rennie Mackintosh, or German and Austrian designers, particularly Joseph Maria Olbrich and the less well-known Erich Kleinhempel and his sister Gertrud.53 | ||||||

|

All these designers and architects represented the idealistic reform movement within the applied arts, regardless of the national European diversity of the Arts and Crafts Movement, Glasgow Four, art nouveau, Jugendstil, and Sezession. But in the Netherlands a very precise distinction was made between what was good modern design and what was bad modern, and there was a discussion taking place about what was the proper style for Dutch designers to propagate. In the latter half of the 19th century this issue had already been discussed with regard to architecture. But the establishment of the Arts and Crafts gallery made it a topical problem for designers in the years around 1900. The inspiration from British sources, for example, was obfuscated in Arts and Crafts' 1901 sales brochure by suggesting that the name Arts and Crafts had not been chosen out of sympathy for England or British economic motives, and that the company was entirely Dutch and not a branch of an English company.54 This attempt to distance the gallery from England may be explained by the contemporary political situation, most notably the Boer War in South Africa. The Hague was the town of the Dutch government, and potential Arts and Crafts customers lived there as well.55 But Arts and Crafts did stock some very British-looking pieces of furniture, the most eye-catching of which were copies of a fisherman's and farmer's chair from the Scottish Orkney Islands (fig. 13).56 This shows the link with the vernacular and folk art, which was just as important an aspect of the applied arts in the Netherlands as elsewhere in Europe.57 The Orkney chair was presented as a piece from the Arts and Crafts company and may have been made in the Apeldoorn furniture workshop. | |||||

| The resemblance to English work was, however, not a serious problem for Durch critics and fellow Dutch designers. They had more trouble with Wegerif's German and Austrian models, which they rejected with arguments about nationalism and identity. Criticism of this kind was not specific to the Netherlands, however, since a French critic claimed that the model rooms at the opening of L'Art Nouveau had "the smell of the Englishman, of the Jewess or the cunning Belgian."58 Similarities to German and Austrian designs in Wegerif's work included parabola shapes and shapes reminiscent of Biedermeier furniture, and the decorative ornamentation and the overall lightness of his interiors.59 The criticism came particularly from Amsterdam-based critics and artists, and people influenced by them. They argued that the only correct style was a puritan, truly Dutch style: simple, stark and restrained. Their perspective was emphatically rationalist—striving after an essence of beauty by way of simple forms and good proportions, and without lavish decoration—and therefore nothing new in historical terms. But it now took the form of good and honest manual work, use of materials and emphasis on construction. | ||||||

|

The main reaction to the Arts and Crafts gallery's objectionable internationalist approach came in the form of the Amsterdam gallery 't Binnenhuis in 1900. Most products sold there testified to nationalist principles: they featured minimal ornamentation, construction joints were over-emphasised and the design was straight and stark. Compared to this, Arts and Crafts' furniture was considered modish and eclectic, with exaggerated and therefore pointless ornamentation, and all in all very German (fig. 14). Critics furthermore associated the Arts and Crafts products with capitalism and with designing for profit only. Instead, they claimed, design should support a belief in a more equal and better society. They even spoke of "spiritual purification through abstinence and asceticism."60 The criticism was particularly loud in the context of two exhibitions: Joseph Olbrich's event Ein Dokument Deutscher Kunst in Darmstadt in 1901, and the Esposizione Internazionale d'arte decorativa moderna in Turin in 1902 which was modelled on Darmstadt. The Amsterdam publisher and socialist, Leo Simons, included the Arts and Crafts gallery in his condemnation of Ein Dokument Deutscher Kunst, even though the gallery was not present at this exhibition. He called this exhibition "A Document of the German Art of Tarting Up," and pointed to the danger that the Arts and Crafts gallery would follow the Darmstadt "messiness."61 Simons himself lived in a villa by the influential architect H.P. Berlage where all the rationalist principles proposed had been followed. Berlage had been one of the first negative critics of Arts and Crafts. | |||||

| The designers at the Arts and Crafts gallery, including Wegerif, did not respond to these "accusations". Wegerif made no public comment about particular design principles; he simply made what he personally liked. Nor were German critics concerned; like critics at the Turin exhibition, they praised Wegerif's work highly. In Turin the contrast between strict principles of construction on the one hand and floral, decorative, baroque principles on the other hand—rational versus irrational/emotional—became unmistakable. It is noteworthy that one of the official and lavish photographic folio publications for this exhibition, Turin 1902, that was published by the Berlin publisher Ernst Wasmuth who also documented Olbrich's work, features no examples of strict rationalists. Out of a total of fifty buildings and interiors, the hall that Wegerif designed and furnished with several pieces of furniture was the only Dutch work included, alongside work by Olbrich, the German artists Bruno Paul and Wilhelm Kreis, the Belgian Victor Horta, and the Italian Raimondo d'Aronco. In his foreword to the publication, the German Leo Nacht explained: "But in Turin there was a lot of purposelessness, a great deal of unconstructiveness… In us there is a deep longing, but not for bare construction and blinkered purposefulness, but for artistic liberation from the pure material foundations of our art."62 The furniture in Wegerif's Turin hall (fig. 15) reminded foreign critics of the Viennese designer Olbrich, who was working in Darmstadt at the time. The German critic Georg Fuchs, also from Darmstadt, proclaimed the work as an example of a Pan-Germanic aesthetic.63 Italian critics found that their architects, such as Raimondo d'Aronco, were also very much indebted to Olbrich.64 | ||||||

| Yet, this hall was still reminiscent of Bing's example of L'Art Nouveau. Decorated with panels by the Dutch painter Frans Stamkart, it followed the decorative scheme of several rooms in the first exhibition at L'Art Nouveau, such as Van de Velde's dining room with painted panels by Paul-Elie Ranson, and Paul-Albert Besnard's ground floor circular salon with panels.65 The use of large painted wall decorations with symbolist iconography, such as Stamkart's allegorical panels of Dawn, Day, Evening and Night, was uncommon in interiors from the Dutch design reform movement. With a few exceptions, architects and designers preferred wallpaper, wooden panelling or bare brick walls, as in the villa interiors of H.P. Berlage.66 | ||||||

| Turin was the high point of the brief involvement of Chris and Agathe Wegerif and the Arts and Crafts gallery in the Dutch movement for the renewal of the applied arts and the shake-up which this brought about. Just over a year later the gallery went bankrupt and business manager John Uiterwijk departed for New York in August 1904. This removed the "danger" of licentiousness through design. The Amsterdam counterweight 't Binnenhuis remained in existence long after; it placed Dutch rationalism firmly on the map. However, just like his wife Agathe who continued with batik, Wegerif continued to build villas. In 1918 the German magazine Innen-Dekoration, which was published in Darmstadt, again featured a lavishly illustrated article about his work.67 The photographs of the villa interiors show that Wegerif remained true to his earlier work and sources of inspiration. | ||||||

| Conclusion Siegfried Bing's L'Art Nouveau in Paris was a model for the Dutch Arts and Crafts gallery in The Hague and was linked to it in various ways. Perhaps the most important connection between them was the Belgian artist-designer Henry van de Velde, who exhibited in both galleries. Like L'Art Nouveau, Arts and Crafts presented modern artifacts and decorative art in model rooms with modern furniture. The Dutch gallery also had workshops where it produced batik textiles, furniture and copperwork. What set Arts and Crafts apart from L'Art Nouveau was the leading role of women. Agathe Wegerif, wife of the gallery's owner, was important both as the leader of the Arts and Crafts batik workshop and as a designer. |

||||||

| Another important difference between the two galleries was their relation to issues of nationalism. While the patent internationalism of L'Art Nouveau was noticed but virtually unquestioned, Arts and Crafts got caught up in a major debate about nationalism in Dutch design. From the start the gallery was regarded as un-Dutch, especially by Amsterdam-based artists and critics. First criticism was directed against the Belgian-French influences, later on the German and Austrian influences were found to be problematic. Design critics in Holland wanted a Dutch style that would suit the character of the Dutch. The debate about eclectic internationalism and principal nationalism turned into a debate about irrational and rational design and became part of a rivalry between The Hague and Amsterdam designers. The ideology of rationalism had a great influence on Dutch design between 1898 and 1904 but would continue long after. Even the difference in furniture design between Amsterdam and The Hague can be found well into the twenties, although the dominant artistic style developed in each of those cities was just the reverse of that which existed there at the turn of the century. But that is another story. | ||||||

|

I would like to thank Petra Chu and Robert Alvin Adler for their helpful suggestions in the editing of this paper. 1. See also Titus M. Eliëns, Marjan Groot, and Frans Leidelmeijer, eds., Avant-garde Design. Dutch Decorative Art 1890-1940, (London: Philip Wilson, 1997), 42-47. So far, this is the most complete survey in English on Dutch decorative art of this period, with a lexicon of artists, companies and workshops. The Arts and Crafts Gallery is discussed here in general. This gallery is a well known and often mentioned aspect of the history of Dutch decorative art around 1900. The first documented article on the gallery was written in 1982 by Joke de Mooy, "Kunsthandel Arts and Crafts in Den Haag, 1898-1904," Kunstlicht (winter 1982-1983): 8, 19-23. But a reconstruction of the gallery's premises and a detailed factual analysis of the artifacts it showed—as has been done with Bings L'Art Nouveau—has not yet been made. 2. For Siegfried Bing and his Salon de L'Art Nouveau: Gabriel P. Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing: Paris Style 1900 (New York and Washington: Harry N. Abrams and the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, 1986); Gabriel P. Weisberg, Edwin Becker, and Évelyne Possémé, eds., The Origins of L'Art Nouveau, The Bing Empire. Exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum; Paris: Musée des Arts Décoratifs; Antwerp: Mercatorfonds, 2004). 3. Johan Thorn Prikker to Henri Borel, November 1895, in Joop M. Joosten, De Brieven van Johan Thorn Prikker aan Henri Borel en anderen 1892-1904: Met ter inleiding fragmenten uit het dagboek van Henri Borel 1890-1892, (Nieuwkoop: Uitgeverij Heuff, 1980), 238, letter 43. On January 6, 1896, he again wrote that his work was at Bing's gallery; Joosten, De Brieven, 241, letter 47. 4. Quote from a letter from Johan Thorn Prikker to Henry van de Velde, January 1898, in Joosten, De Brieven, 266, letter 67: "Beste vriend. Een van m'n kennissen zal in den Haag 'n kunstzaak beginnen, iets in de geest zooals die van Bing in Parijs. Behalve enkele schilderijen wilde hij speciaal toegepaste Kunst tentoonstellen. Ik heb hem aangeraden eens bij jou aan te komen, om je steun te vragen, en buitendien om van jou adressen, en liefst aanbevelingen voor Belgischen en Franschen artiesten te krijgen." For his difficulties with batik, ibid., pages 252, letter 53, 263, letter 65, 264, letter 66. 5. W. Crane, "Decorative Art at Turin: Notes upon some of the Sections," The Art Journal, n.s., (1902): 261. 6. Catherine Krahmer, "Über die Anfange des Neuen Stils: Henry van de Velde * Siegfried Bing * Julius Meier-Graefe," in Klaus-Jürgen Sembach and Birgit Schulte, eds., Henry van de Velde: Ein europaïscher Künstler seiner Zeit (Cologne: Wienand Verlag, 1992), 162. 7. Compare with p. 49 in Klaus-Jürgen Sembach, Henry van de Velde (New York: Rizzoli, 1989), and Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, fig. 59, right. For Thorn Prikker's visits to Bloemenwerf: Joosten, De Brieven, 252, letter 53, 21 November 1896. Van de Velde had a photo of Thorn Prikker in his study at Bloemenwerf. See Sembach and Schulte, Henry van de Velde, 218, fig. 45. 8. Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 66-70. 9. Évelyne Possémé, "Bing and England," in Weisberg, Becker, and Possémé, The Origins of L'Art Nouveau, 153-162. 10. Sembach, Henry van de Velde, 11-16, 35-36. 11. Weisberg, Becker, and Possémé, The Origins of L'Art Nouveau, 154. 12. Parts of these interiors in Wolf D. Pecher, Henry van de Velde: Das Gesamtwerk, vol. 1 (Gestaltung) , (Munich: Factum, 1981), 124-127. The dining room mantelpiece was again exhibited in Vienna in December 1900. 13. For a contemporary photograph of the Biart-interior, see Pecher, Henry van de Velde, 99, and Sembach, Henry van de Velde, 55; for references to the 1899 catalogue, see Pecher, Henry van de Velde, 124-125. 14. J.V. [Jan Veth], "Een nieuwe kunsthandel," De Kroniek 4 (4 september 1898), 289, for Brangwyn, Köpping, and Tiffany. This review gives the Dutch word "tapijt" for the two Brangwyn pieces. This probably refers to carpets, although in Dutch the word means tapestry as well. There is a color illustration of the "Japanese Vine" carpet in Weisberg, Becker and Possémé, The Origins of L'Art Nouveau, 152, fig. 159, and a second, smaller bedside carpet from ca. 1898 with less bright colors on 160, fig. 175. 15. J.V., "Een nieuwe kunsthandel." 16. J.H.S., "Kunstnijverheid," De Amsterdammer, 18 September 1898. 17. J.V., 'Een nieuwe kunsthandel'. Six pieces of Finch pottery for the Arts and Crafts gallery are now in the collection of the Central Museum, Utrecht. 18. G., "Kunst*en Letternieuws," Het Vaderland 10 August 1898. 19. J.H.S., "Kunstnijverheid." 20. G., "Kunst*en Letternieuws." 21. Ibid. The carpets/tapestries may have been the two Brangwyn pieces and the other products probably included those from the mentioned artists. 22. J.V., "Een nieuwe kunsthandel," and "Letteren en Kunst. In Den Haag," Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant 28 August 1898. 23. "Letteren en Kunst;" J.V. "Een nieuwe kunsthandel." 24. I would like to thank Martin Eidelberg for this suggestion concerning the Tiffany glass. 25. Joosten, De Brieven, 238 letter 43. 26. The Netherlands had already established trade contacts with Japan in the early 17th century. See Stefan van Raay, ed., Imitation and Inspiration. Japanese Influence on Dutch Art (Amsterdam: Art Unlimited Books, 1989). In the 19th century Japanese artifacts were collected by Philippe Franz von Siebold, who had a cabinet with Japanese artifacts and displayed a choice of these artifacts at national Dutch exhibitions. However, artists of the Dutch reform movement did not use Japan as a source of inspiration until the 1890s. 27. Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 31-32. 28. Joosten, De Brieven, 238, letter 43; Mienke Simon Thomas, De leer van het ornament: Versieren volgens voorschrift 1850-1930 (Amsterdam: De Bataafsche Leeuw, 1996), 142-151. 29. Titus M. Eliëns, "Dutch Lacquerwork in the Nineteenth Century," in Imitation and Inspiration, 87-88; Eliëns, "Haagse interieurs rond 1900," in Den Haag rond 1900: Een bloeiend kunstleven (Blaricum: V+K Publishing, 1998), 25-26. 30. Bing had workshops from 1898 onwards for jewelry and metalware, furniture, handbags, carpets, fabrics, tapestries, and ceramics. In 1899 he enlarged his workshop space. Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 142-151, and Gabriel P. Weisberg, "Redesigning the Home: Bing's Art Nouveau Workshops," in Weisberg, Becker and Possémé, The Origins of L'Art Nouveau, 165-173. 31. G. Heuvelman, "Batikken: Een nieuwe tak van kunstnijverheid in Nederland," Eigen haard (1900), 229. Recently, for Wegerif in general: Marjan Groot and Hanneke Oosterhof, Textielkunstenaressen art nouveau art deco 1900-1930 (Tilburg: Dutch Textile Museum, 2005). 32. The manuscript is now in the possesion of relatives of Agathe Wegerif. 33. For these workshops, see Susan Legêne and Berteke Waaldijk, "Reverse Images*Patterns of Absence: Batik and Representation of Colonialism in the Netherlands," in I. van Hout, ed., Exh. cat. Batik-Drawn in Wax: 200 Years of Batik Art from Indonesia in the Tropenmuseum Collection (Amsterdam: Royal Tropical Institute, 2001), 34-65. 34. Heuvelman, "Batikken," 231. 35. Ibid., 230. 36. Illustrated in Pecher, Henry van de Velde, 102, and 270 (reproduction of catalogue page showing items 1109, 1109a. In his caption, Pecher mentions that the chair was exhibited at Meier-Graefe's La Maison Moderne in 1899-1900, but this seems to be wrong; Sembach, Henry van de Velde, 218, and fig. 51; Weisberg, Becker and Possémé, The Origins of L'Art Nouveau, 106 fig. 109 (in color). The chair was also made with a woven cover from the weaving colony Scherrebeck in Germany. After mid-1898 Bing reported that he had no more furniture by Van de Velde and was coordinating the manufacturing of furniture himself. Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 145. 37. Letter from Johan Thorn Prikker to Henry van de Velde, 26 July 1897, in Joosten, De Brieven, 258, letter 60, and 260, letter 63. For the relation between Van de Velde, Bing, and Meier-Graefe, see Krahmer in Sembach and Schulte, Henry van de Velde, 149-162. 38. Heuvelman, "Batikken," 230. 39. G. Fuchs, "Holländische Innenräume. II. Chris und Agathe Wegerif * Apeldoorn," Innen-Dekoration 15 (1904), 45 40. Cf. a favorable review by Tom Schilperoort, "Batikwerk als industrie," Op de Hoogte 7 (1910), 623-627. 41. Yvonne Brunhammer and Suzanne Tise, French Decorative Art: The Société des artistes décorateurs 1900-1942 (Paris: Flammarion, 1990), 284. 42. Gabriele D'Annunzio, Forse che si, forse che no. (n.p.,1910; Milan: Mondadori, 1981), 289-290 (Citation to the 1981 edition). 43. Marjan Groot and Hanneke Oosterhof, Handleiding bij de tentoonstelling Chris Wegerif (1859-1920) en Agathe Wegerif-Gravestein (1867-1944) meubel-, textiel- en bouwkunst 1896-1920 (Historical Museum Apeldoorn: Apeldoorn, 1995-1996), 9-12 for a short list of exhibitions and biographical facts; Hanneke Oosterhof, "Agathe Wegerif-Gravestein (1867-1944) Sierkunstenares en schilderes" (Drs. thesis, Open University Heerlen, 2001), 114 (list of exhibitions). The exhibition lists in both publications were compiled from a scrapbook of Agathe Wegerif containing newspaper reviews, now in the possesion of relatives of Wegerif. 44. Collection Municipal Museum, The Hague. 45. Jacq. R.v.S. [Jacqueline Reyneke van Stuwe], "Batikwerk," De Haagsche Vrouwenkroniek 4 (24 November 1917), 47. Color illustrations and a discussion of her work in Groot and Oosterhof, Textielkunstenaressen, 2005, 40-45. 46. Quote from Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 240. For leather bookbindings by Eva Mannerheim Sparre, Alexandra Thaulow, and Antoinette Vallgren, and on the the Rookwood painters Rose Fechheimer, Anna Marie Valentien, and Josephine Zettel, see Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 41-42, 125, 131 and figs. 68, 69, 131, and 236; for portraits by Marie Bermond, ibid., 230-233, 235; for sculptures by Meta Warrick, ibid., 240. 47. 'T.K.L. Sluyterman, "_Modern Arts and Crafts Movement in Holland,' The Art Workers Guild London 27 March 1903", De Bouwwereld (1903), 112. 48. De Mooy, "Kunsthandel Arts and Crafts." 49. Eliëns: "Haagse interieurs," 22. The firm, called Binnenhuis Die Haghe, sold art, contemporary decorative art (ceramics from Amstelhoek and Willem Brouwer), and antiques, and had a furniture and metal workshop. The villa in The Hague that Van de Velde designed for doctor W.J. Leuring was the (still well-preserved) villa De Zeemeeuw (The Seagull), 1901-1902. See Pecher, Henry van de Velde, 193-194. 50. Frans Netscher, Joh. Th. Uiterwijk Arts and Crafts, (n.p., n.d.,[The Hague 1901]). There are a few copies of this brochure in various archives. One, with a parchment leather binding, is in the collection of gifts presented to the Royal Family, part of the Royal Family Archives in The Hague. Another one, with a paper cover, is in the library of the Municipal Museum, The Hague. 51. "Studio Talk," The Studio 23, no. 101 (1901): 209-210. 52. When I documented the album in 1995-1996, it was in the collection of the Museum Simon Van Gijn in Dordrecht, a museum with important 18th and 19th-century period rooms. The curator of the museum informed me in 1995 about the album after he had heard of the preparations I was working on at the time for an exhibition on Wegerif. Dordrecht had nothing to do with the Arts and Crafts gallery, and it is unclear how the album came in the possession of this museum and its provenance was not registered. The quality of the photographs indicates that it was an unofficial album; they seem to have been taken with little regard for the quality of the image, as though the only goal was to create a visual inventory of the pieces. There were no written notes in the album that could clarify this any further, and I have not found other clues afterwards. Most pieces of furniture we know today are in the collection of the Municipal Museum, The Hague. A few are in the Historical Museum Apeldoorn, and a number are still in the possession of relatives of Wegerif. 53. For an analysis of the stylistic similarities, (in Dutch but with many illustrations), comparing the furniture of the Arts and Crafts gallery with examples from the mentioned artists see Marjan Groot, "Een dilemma voor de Nieuwe Kunst. Modern eclecticisme in de meubelkunst van Chris Wegerif voor de firma Arts and Crafts, 1901-1906," Jong Holland 14, no. 2 (1998): 36-51. Wegerif's furniture is indebted to Mackintosh. Cf., Alan Crawford, Charles Rennie Mackintosh (London: Thames and Hudson, 1995), 138-139, who asserts that it is hard to find Mackintosh's influence with European designers. 54. Netscher, Joh. Th. Uiterwijk,, 6-8, 19. 55. The Boer War, also called Second Transvaal War in South Africa (1899-1902), was a conflict between the British and the Boeren (Dutch, but also German and French colonists), from the republics Oranje Vrijstaat and Transvaal. From the First Transvaal War in 1877 onwards their independence was threatened by British annexation. Because of the war, many Dutch preferred to leave the country instead of submitting to a British government. 56. In Wegerif's family, the Scottish Orkney-Chair was also called the Transvaal-chair. 57. Nicola Gordon Bowe, ed., Art and the National Dream. The Search for Vernacular Expression in Turn-of-the-Century Design (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 1993), with essays on this subject for, e.g., Japan, America, Russia, Poland, Hungary, Norway, Finland, and Ireland. The Netherlands are not included, but would have been a good subject, too. 58. Quoted in Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 77. Stark contrasts between artists from different countries exhibiting at Bing were also noticed. See for this Possémé, "Bing and England," 152-153. 59. In this respect, a comparison with the work of Olbrich that was published at the time Wegerif designed for the Arts and Crafts gallery is rewarding. See for this the sketches by Olbrich in Ideen von Olbrich, (Stuttgart: Arnold'sche, 1992), (facsimile of the second edition by Ludwig Hevesi, Leipzig 1904; first edition published in Vienna in 1899); Joseph Maria Olbrich: Vollständiger Nachdruck der drei Originalbände von 1901-1914 (Tübingen: Wasmuth, 1988) (originally published as: Architektur von Olbrich (Berlin: Ernst Wasmuth, 1901-1914). 60. "… geestelijke zuivering door onthouding en ascetisme." L. Simons, "Een Dokument van Duitsche opdirkings-kunst," Onze kunst 1 (1902), 48-53. 61. Ibid. The exhibition Ein Dokument deutscher Kunst was documented by A. Koch, Die Ausstellung der Darmstädter Künstlerkolonie: Ein Dokument deutscher Kunst (Darmstadt: Alexander Koch, 1901). In 1996, the museum of this German artists' colony did not have any work by Wegerif. Letter from dr. R. Ulmer to M. Groot, 29 May, 1996. 62. Leo Nacht, Turin 1902 (Berlin: Ernst Wasmuth, 1902), Foreword, "In Turin aber gab es viel Unzweckmäsziges, viel Unkonstruktives.… In uns steckt eine tiefe Sehnsucht, aber nicht nach der nackten Konstruktion und der philiströsen Zweckmäszigkeit, sondern nach künstlerischen Befreiung von den rein materiellen Grundlagen unserer Kunst …". This rare publication is in the collections of the National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and Harvard University's Frances Loeb Library. 63. E. Thovez, "The International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art at Turin * The Dutch Section," The Studio 26 (1902): 113, 203-213; Georg Fuchs, L'Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs Modernes (Darmstadt: Alexander Koch, 1902). Also, Debora J. Meijers, "Holland und die Gross-Deutsche Kultur; Een Duitse reactie op de Nederlandse 'Nieuwe Kunst,'" Bulletin geschiedenis Kunst en Cultuur 3, no. 3 (1994): 206-234. 64. See E. Godoli, "_... uno stile uniforme, che non è altro che lo stile austro-tedesco,' Polemiche sull'architettura dell'esposizione," in R. Bossaglia, E. Godoli, and M. Rosci, eds., Exh. cat. Torino 1902. Le Arti Decorative Internazionali del Nuovo Secolo (Turin: Fabbri editori 1994), 66-69. 65. A contemporary photograph of this room is in Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 70, fig. 62, and in Weisberg, Becker and Possémé, The Origins of L'Art Nouveau, 109, figs. 113 and 114 (with one panel by Ranson, 1895, in color), 124 and 12,5 fig.129 (three of eleven decorative panels from the circular salon by Besnard, c. 1895, in color). 66. For photographs of this, see Karin Gaillard, "Sobere eerlijkheid, behaaglijke eenvoud. Het binnenhuis volgens Berlage," in Ellinoor Bergvelt, Frans van Burkom, and Karin Gaillard, eds., Van neorenaissance tot postmodernisme/From neo-renaissance to postmodernism. Honderdvijfentwintig jaar Nederlandse interieurs/A hundred and twenty-five years of Dutch interiors 1870-1995 (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 1996), 60, plates 45-47, and 68, plates 61-63. Cf., Marjan Groot, "Revolutionaire weelde en ambachtelijke schoonheid: Van Wisselingh en Arts and Crafts," in idem, 99-109. 67. Wolfgang Breithaupt, "Holländische Land- und Strandhäuser erbaut von den Architekten Han & C. Wegerif und Frau Agathe Wegerif-Gravestein," Innen-Dekoration 29 (October 1918), 265-288.

|