The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

NOTE: selected images are accessible via external links, which each launch in a new browser window.

Gabriel P. Weisberg with contributions by Edwin Becker, Maartje de Haan, David Jackson, Willa Z. Silverman, with the collaboration of Jean-François Rauzier,

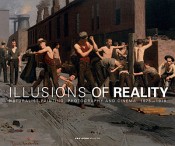

Illusions of Reality: Naturalist Painting, Photography, Theatre and Cinema, 1875 – 1918.

Published in conjunction with the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, and the Ateneum Art Museum, Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki.

Brussels: Mercatorfonds, 2010.

224 pp.; 68 b/w illustrations, 234 color illustrations; bibliography; index.

€34.95

ISBN: 978-90-6153-941-4 (English)

Illusie en werkelijkheid: Naturalistische schilderijen, foto's, theater en film, 1875 – 1918

ISBN: 978-90-6153-939-1 (Dutch)

L'illusion de la réalité: la peinture naturaliste, la photographie et le cinéma, 1875 – 1918

ISBN: 978-90-6153-940-7 (French)

Illusions of Reality: Naturalismus 1875 – 1918.

Stuttgart: Belser Verlag, 2010.

€39.95

ISBN: 978-3-7630-2577-0 (German)

Arjen sankarit: Naturalismi kuvataiteessa, valokuvassa ja elokuvassa 1875 – 1918.

Helsinki: Ateneum Art Museum, Finnish National Gallery, 2011.

€32

ISBN: 978-90-6153-990-2 (Finnish)

Vardagens hjältar: Naturalismen i bildkonsten, fotografiet och filmen, 1875 – 1918

ISBN: 978-90-6153-991-9 (Swedish)

The critic Jules Castagnary called the Paris Salon of 1863 "tumultuous." Despite the noise and confusion, he discerned in the exhibition, on view at the same time as the Salon des refusés, three schools of contemporary art: the classic and romantic schools--both moribund--and a young movement with great energy and potential. "The naturalist school," Castagnary observed, "is reestablishing the broken links between man and nature."[1] At the Salon of 1874, the astute critic admired Portrait of My Grandfather by Jules Bastien-Lepage and cast the young painter as the leading man for the new school. The catalogue for Illusions of Reality decisively confirms that Bastien-Lepage maintained that position long after his early death ten years later.[2] Of the thirty-eight painters selected forthis superb international survey of late-nineteenth-century naturalist art at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam in late 2010, Bastien-Lepage is one of five who showed works in the Salon of 1874. By 1880 seven additional painters included in Illusions of Reality were exhibiting at the Paris Salon, and the new movement triumphed in the awards ceremony. Two of the winning canvases from 1880 hung in the Amsterdam show: The Good Samaritan (202), which earned Aimé Morot the Salon medal of honor, and Conveying the Child's Coffin (172), for which the Finnish painter Albert Edelfelt received a third-class medal.[3] The decade of the 1880s, when the Third Republic became more truly republican, was the heyday of the naturalists: two thirds of the paintings on view at the show in the Van Gogh Museum were painted between 1879 and 1889.

That a sweeping and virtuosic account of the naturalist movement – both in its prime and its aftermath – would be mounted at the Amsterdam museum is apposite and moving, given the avid interest Vincent van Gogh took in the new school. Living in Holland, he followed the careers of Salon artists through reproductive wood engravings in the French press. From The Hague, Vincent wrote in late 1882 to his brother Theo, reporting his enthusiasm for The Accident and other works by Pascal Adolphe Jean Dagnan-Bouveret.[4] By the end of March 1883, he had seen a reproduction of Léon Lhermitte's The Grandmother and told Theo that the image had stayed in his mind for days.[5] Bringing the naturalist master works to Amsterdam in 2010 amply provided a context for Van Gogh's artistic formation and introduced to a new public dozens of artists scarcely known even in their own countries.[6] The exhibition (reviewed separately in this issue) took an original approach to the later years of the movement and its far-flung manifestations in Europe and the United States and will have a long shelf life in an intelligently designed and bountifully illustrated catalogue.

Differentiating naturalism from realism tends to clot discussions of late nineteenth-century art. Deftly avoiding that hazard in their introductory essay for Illusions of Reality, Edwin Becker, curator of exhibitions at the Van Gogh Museum, and Gabriel P. Weisberg, whose Beyond Impressionism: The Naturalist Impulse (1992) remains the standard work on the subject, offer the reader two first-rate – if second-hand – definitions. First, they cite the lucid essay published in 1982 by Geneviève Lacambre, then chief curator at the Musée d’Orsay (14). She pointed to characteristics of naturalism: "scientific exactitude, psychological examination, and a large-scale format" and the practice of "showing their subjects as if caught – frozen – in a specific, characteristic instant, akin to the photography of the period in their attitude, though not in their scale."[7] The authors also quote Castagnary's Salon of 1863 (15): "The naturalist school declares that art is the expression of life in every way and degree, and that its singular goal is to reproduce nature to its maximum power and intensity: it is truth balancing itself with science."[8]

Rather than belabor terminological issues, the authors take the reader straight to the 1880s through images of stunning naturalist paintings from that decade. A full-page detail from At the Printer's (1884; Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam) by the Austrian artist Felician von Myrbach-Rheinfeld serves as a frontispiece to the introduction.[9] This subtly brilliant interior of an intaglio workshop, first shown in the Salon of 1884, corresponds – except in scale – to the definitions quoted above. So does Fernand Pelez's Homeless (1883; Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris), which gave Salon-goers in 1883 a frontal view of poverty in the capital. The misery of this dislocated family – the reproduction stretches across the book's gutter – is an emblem for the pages that follow. In the first chapter Weisberg outlines the exhibition's themes: work in fields and factories, social change, the suffering of the poor, the invasive effects of photography, the dominant influence of Emile Zola, and, most surprisingly, the move of naturalist narrative and pictorial effects from the Salon to the motion picture screen. Photographs by Peter Henry Emerson, the English author of Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art (1889), are reproduced with works by his painter compatriots George Clausen and Henry La Thangue. All three worked in the wake of Bastien-Lepage, whose powerful presence in Britain is suggested by The Woodgatherer (Le père Jacques, 1881; Milwaukee Art Museum), exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1882 and sold in London. Another fervent admirer of Bastien-Lepage and a photographer himself, Emile Zola is introduced in the first chapter as a strong thread that will run through the catalogue.

The second chapter, "Photography as Illusionary Aid," features Jules-Alexis Muenier, an artist who worked as both painter and photographer; two of Muenier's cameras were included in the exhibition (33).[10] Thomas Eakins, the best-known painter-photographer in the United States, and his pupil Thomas Anshutz close the chapter. The Anshutz painting entitled The Ironworkers' Noontime (1880; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco) appears on the catalogue cover. Weisberg continues the story of this key work in Chapter Three, reproducing photographic figure studies of men posing outdoors, tentatively attributed to Anshutz, which may have been used in positioning the workers for his canvas.[11] Images depicting rural and industrial toil document the rapid social changes affecting workers across Europe, from Russia to England, as well as in America. Striking photographs by Félix Thiollier record the activities of coal gleaners and miners near his home town of St. Etienne, southwest of Lyon. Swiss craftsmen are celebrated by the painter Edouard Kaiser in a double-spread detail of Watch Metal Casings Atelier (1898; Musée des Beaux-Arts, La Chaux-de-Fonds). Discussing Eugène Buland's six-foot-long canvas of a man peddling portrait prints of the renegade General Georges Boulanger, Propaganda Campaign (1889; Musée d’Orsay, Paris), Weisberg cites a Salon critic's observation that Buland had treated the scene with the indifference of a photographer: "His tableau is not Boulangist. It is also not antiboulangist."[12] (71) An insightful passage on naturalist religious painting is illustrated by several works, among them The Sermon (1886; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC) by Gari Melchers. The chapter ends almost light-heartedly with a discussion of youth. One of the painted classroom scenes is The Drawing Lesson in a Primary School, first shown at the Salon of 1895 and among the six large works commissioned from Jean Geoffroy by the Education Ministry (79–80). If the rarely-seen Geoffroy canvas recalls the Jules Ferry legislation of 1881–82 that made education in France free and compulsory, those by Karoly Ferenczy and Emile Friant show boys simply enjoying themselves outdoors.

A formidable task underlies the evaluation in the fourth chapter of the critical reception of naturalist painting. Comparatively free of censorship in the 1880s, the French press burgeoned, and nearly every newspaper and magazine covered the annual Salons in articles running over multiple issues. After the Salon split in 1890, the art reviews doubled. Weisberg prudently focuses on a handful of painters, among them Fernand Pelez. A detail of his Grimaces and Misery (1888; Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris) – a painting more than twenty feet long – forms a spectacular centerfold for the book, a digital echo of the two-page color spread in L'Illustration in 1888, also reproduced in the catalogue (85).[13] Another widely discussed painting in the Amsterdam show, The Black Stain (1887; Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin) by Albert Bettanier, drew attention at the Salon of 1887 by its blatant reference at the peak of the Boulangist movement to the disputed territory of Alsace-Lorraine.

In Chapter Five, David Jackson, an art historian at the University of Leeds, ably guides the reader to the "Natural North: Russia and the Nordic Countries." Jackson describes a delayed development of alternative exhibition societies in Scandinavia and a strict censorship that restricted possibilities for the Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) in Russia (102). At the same time, provocative indigenous literary traditions made Zola's influence somewhat less important. Bastien-Lepage, however, became the "creative conduit" for the northern artists (104). Parker launches a stimulating discussion, to be taken up in later chapters, on the "bequest" that naturalist painting made to theatre and film.[14] The "illusion of reality," suggests Willa Z. Silverman in Chapter Six, was best conveyed in the theatre (129). A professor of French and Jewish Studies at The Pennsylvania State University, Silverman outlines the reform Zola demanded in Le Naturalisme au théâtre (130– 34). In Zola's text – first published in January 1879, when his "unlikely collaboration" with William Busnach began with L'Assommoir at the Théâtre de l'Ambigu – the writer demanded truth onstage, railing against the ‘well-made play' and Jacques Offenbach operettas. In a preface to the published drama in 1881, Zola defended his choice of the showman Busnach, noting with pride that L'Assommoir had run for more than 300 performances.[15]Germinal, Busnach's fifth and final staging of a Zola novel, was less fortunate. Scheduled to open some months after the novel appeared in March 1885, the play was banned by the Minister of Public Instruction, René Goblet; Silverman refers in a footnote to the furious letter Zola published in Figaro (130, n. 8). Opening at last on April 21, 1888, at the Théâtre du Châtelet, Germinal ran for only seventeen performances.[16]

In a seamless transition to Weisberg's Chapter Seven on early naturalist cinema, Silverman closes her essay on theatre with André Antoine, founder of the Théâtre Libre (1887– 94), "the man who in fact cast himself as Zola's heir." (137). He also cast himself as the lead (lepère Fouan) in a production of La Terre; the play opened at the director's subsequent theatre, the Théâtre-Antoine, on January 21, 1902, and Zola died of asphyxiation in September of that year. Critics were not all beguiled by the livestock and free-ranging poultry onstage in La Terre, illustrated by Silverman and Weisberg (138-9, 149-50). Gaston Leroux, for example – later the author of Le Fantôme de l'Opéra (1910) – wrote in Le Matin: "It is not with . . . some hay, real hay, and three hens, real hens . . . it is not with these props, however cleverly chosen, placed, and arranged, that one can create an atmosphere evoking the peasant soul . . . that lives in the 500 pages of Zola's novel."[17]

If stage sets failed to transmit a naturalist novel's illusions of reality, a potent new medium was at hand. Demonstrating uses early filmmakers made of naturalist painting, Weisberg discusses some of the many film treatments of Zola novels before 1918 (144–53). One of the masters of the silent era was a former actor for Antoine at the Théâtre Libre, Albert Capellani. He filmed Germinal (1913) on location, documenting the miners and their dwellings (corons) in a parallel to Zola's visit to the Anzin mine near Valenciennes to make notes for his novel.[18] Capellani was a child when Alfred Roll exhibited The Miners' Strike (now destroyed) at the Salon of 1880, and when Gaston La Touche made a painting in 1889 (now lost) based on the strike in Germinal. Discussing painted precedents of Capellani's sequence in Germinal, Weisberg illustrates the lost La Touche painting with an image from L'Illustration (April 27.1889). He also reproduces two paintings in the exhibition: The Strike (1886; Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin) by Robert Koehler, and The Strike at Le Creusot (1899, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Pau) by Jules Adler, which received little critical comment when shown at the Salon of 1900 (146–48). The theatre director Antoine returned to Zola's La Terre with a movie version (released 1921), filming on location in the Beauce region, near Chartres, in 1918-19; he also scouted for locations in the Camargue for his last film, Alphonse Daudet's L'Arlésienne (released 1922). His documentary instinct and his insistence on a mobile – not static – camera make Antoine a prime example of the naturalistic cinema. Weisberg closes this magisterial chapter by comparing film stills from La Terre with paintings by Charles Sprague Pearce and Albert Edelfelt (150–53).

In a final chapter on "Naturalism and Dutch Painting," Maartje de Haan suggests that the impact of French Salon art in the 1880s was fleeting. She quotes the painter Jan Veth, who called France a country of "soulless show-offs " (156).[19]Willem Witsen, like Veth a member of the Tachtigers (the Eighties Movement), produced in Gathering Kindling (1886; Private collection) a tribute to the late Bastien-Lepage after seeing his posthumous retrospective in Paris in 1885 (157, fig. 152). Another Tachtiger, Floris Verster, painted Stonecutters (1887; Museum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo), but it remained an anomaly in his work. Although Jan Toorop was touched by the naturalists in the 1880s, his After the Strike (1889; Museum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo) is a neo-impressionist painting. As de Haan points out (157), Toorop veered toward symbolism, as did the Belgian Léon Frederic after The Ages of the Worker (1895–97; Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Another Belgian, Eugène Laermans, treated monumental naturalist subjects that, with hindsight, make him – like Constantin Meunier – a precursor of Belgian expressionism. For his master work Les Emigrants (De Landverhuizers, 1896; Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp), Laermans drew inspiration from a recently published naturalist novel by Georges Eekhoud, La nouvelle Carthage (1893).[20] The Dutch writer Louis Couperus produced a great naturalist novel – Eline Vere (1888) – then moved in new directions. De Haan concludes that the relatively few, short-lived naturalist impulses in the Netherlands did not add up to a significant impact on its art.

From the opening pages through the grandiose 50-page color-plate section – all the paintings in the exhibition are sensitively recombined in pairs – the catalogue enables an unusual visual engagement with the works, beautifully reproduced and generously sized. Embedded in each chapter are connections with the rest of the book, helpfully cross-referenced and supported by a useful index. Weisberg has surveyed "the naturalist landscape" for decades with a tireless intensity. In Illusions of Reality he and a gifted team offer samples from years of excavations. The finds include the initial probes of newly-opened mounds, with material from theatre, photo, and film archives placed in a context of nearly forgotten paintings. Defying indifference, naturalist pictures once moved hardened critics to tears. Many a reader will wonder why these appealing works are so new to them.

Jane Van Nimmen

Independent scholar, Vienna

vannimmen@aon.at

Unless otherwise indicated, translations are by the author.

[1] [Jules-Antoine] Castagnary, "Salon de 1863," Salons (1857–1870), preface by Eugène Spuller, 2 vols. (Paris: G. Charpentier and E. Fasquelle, 1892), 1,105.

[2] On the portrait of Charles Nicolas Lepage, see the entry by Dominique Lobstein, no. 4, 78–79, as well as his introductory essay, in Jules Bastien-Lepage(1848–1884), exh. cat. (Paris: Musée d’Orsay/Nicolas Chaudun, 2007); the catalogue includes a valuable discussion of the artist's widespread influence by Emmanuelle Amiot-Saulnier.

[3] The critic Philippe Burty found Edelfelt's picture so masterly that "a third-class medal hardly suffices": it deserved instead the Légion d'honneur. See Ph[ilippe]. Burty, "Le Salon de 1880,"L'Art 21 (1880), reprinted in Le Salon 1:11 (July 1880), 173. Other prize-winners of 1880 represented with later works in Illusions of Reality include two first-class medalists, Pascale Adolphe Jean Dagnan-Bouveret (The Accident) and Fernand Pelez (At the Public Laundry); both Edouard-Jean Dantan (A Corner of the Studio) and Léon Lhermitte (The Grandmother) won second-class medals.

[4] Van Gogh's interest in the Salon can now be traced on the remarkable site Vincent van Gogh: The Letters [http://vangoghletters.org/vg/]. In each letter, the user can click on the tab "notes," and then on square icons, to view works cited in the annotations, or on the tab "artworks" to see all those mentioned in a letter text. See, for example, Letter 292 (December 10, 1882, n. 10, third paragraph) for a wood engraving by Auguste Louis Lepère after The Accident from Le Monde Illustré 24 (May 22, 1880), 321. In March 1883, writing to his painter friend Anthon van Rappard, Van Gogh added a sketch with a possible source in a reproduction of Bastien-Lepage's October, Potato Harvest (1879, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne); see Letter 325 (click in translated text on Sketch A, 1v, and in notes on square icon in n. 6). Vincent, fully absorbed in peasant life in Nuenen in April 1885, praised October again in a letter to Theo (Letter 493, n. 9).

[5] In Letter 333

(March 29 and April 1, 1883, n. 1), click on the square icon to see the Lhermitte image. Van Gogh collected more Hubert von Herkomer reproductions than those of any other painter in the 2010 exhibition; some twenty-two examples are preserved in the Van Gogh Museum library. A presentation based on Vincent's trove of graphic reproductions ("Vincent van Gogh and Naturalism") ran concurrently with Illusions of Reality in Amsterdam.

[6] Only one Belgian – Emile Claus – was included in the Amsterdam show, possibly because the last grand survey exhibition of naturalist art took place in 1996 in the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp. The Antwerp catalogue exhaustively treated Belgian painting and sculpture; see Herwig Todts, Dorine Cardyn Oomen, Natalie Monteyne, and Leen De Jong, Tranches de vie: Le naturalisme en Europe 1875–1915, or the Dutch edition Het volk ten voeten uit : naturalisme in België en Europa: 1875–1915 (Ghent: Ludion, 1996). In a review of Illusions of Reality, Tilman Krause noted that Germany was represented by only one artist with a single canvas: Wilhelm von Uhde's Let the Little Children Come to Me

(1884, Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig). Krause commended the Van Gogh Museum for its dedicated reassessment of the "paramodern," the alternative movement to the succession of avant-gardes; see "Die Elende standen vor den Salons. Und sie wurden gemalt," Die Welt, November 12, 2010.

[7] Geneviève Lacambre, "Toward an Emerging Definition of Naturalism in French Nineteenth-Century Painting" in Gabriel P. Weisberg, The European Realist Tradition (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982), 229, 238–39.

[8] Castagnary, Salons, 1:104–05, as in n. 1.

[9] The graphic artist Felician von Myrbach-Rheinfeld served as rector (1899-1905) of what is now the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. In 1898 a founding member of the Vienna Secession, he took the side of Gustav Klimt and the Austrian "stylists" in 1905 in their quarrel with the "naturalists" and resigned from the group. His case demonstrates the complex forces that compel an artist to change "isms."

[10] Weisberg credits the contribution of Jean-François Rauzier to the chapter on photography, particularly in locating Muenier's camera equipment. On Muenier, see Itinéraires champêtres: Jules-Alexis Muenier, 1863–1942, peintre sous la IIIe République. exh. cat. (Vesoul: Musée Georges-Garret, 2003), and Gabriel P. Weisberg. "J. A. Muenier and Photo-Realist Painting," Gazette des Beaux-Arts 121 (February 1993), 101–14, as well as Weisberg, Beyond Impressionism, 34-40.

[11] Weisberg identifies the site as the Belmont Nail Works on the Ohio River in Wheeling, W. Virginia, a town where Anshutz had spent time as a child and a center for the cut nail industry (46–49). In a further "illusion of reality," The Ironworkers' Noontime entered advertising history in 1883, when Harley Procter commissioned the Strobridge Lithographing Co. to create a large composite poster for Ivory soap, based on posed photographs and a painted factory backdrop; see Ruth Bowman, "Nature, The Photograph and Thomas Anshutz," Art Journal 33 (Autumn 1973), 32-40. Wheeling was also the setting for what may be the first naturalist novella in American literature: "Life in the Iron-Mills," Atlantic Monthly 7:42 (April 1861), published anonymously by Rebecca Harding Davis, the reformer and journalist, who grew up in the rapidly industrializing river town. At the end of September 2010, a week before the Anshutz painting went on view in Amsterdam, the last Wheeling cut nail factory, the LaBelle Nail Co., closed down when it could not replace its blacksmith.

[12] Boulanger, who had posed the threat of a coup d'état, had fled Paris a month before the Salon of 1889 opened with Buland's painting on display. On Buland, see Eugène Buland: Aux limites du realisme, 1852–1926, exh. cat. (Paris: Panama, 2007).

[13]L'Illustration 92 (September 29, 1888), 240. See Isabelle Collet, ed., Fernand Pelez: La Parade des Humbles, exh, cat. (Paris: Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, 2009), and the reviews in The Art Tribune and in this journal (Autumn 2010).

[14] Parker's case study of the Norwegian painter Christian Krohg is particularly apt, as are his comments on the use of photography by Eero Järnevelt in Under the Yoke (1893; Ateneum Art Museum, Finnish National Gallery).

[15] Busnach's recent works had included the libretto (written with his cousin Ludovic Halévy) to Offenbach's hour-long romp Pomme d'api (1873) and the boulevard comedy Mon mari est à Versailles (1876); he would later collaborate with Guy de Maupassant and Jules Verne.

[16] Adrien Barbusse protested the earlier censorship in his review of Germinal for Le Siècle

, April 22, 1888, 3, cited by Silverman (130, n. 9). He found Busnach's twelve tableaux dramatic, but hardly an advance over the ‘well-made play.' Barbusse was the father of the naturalist novelist Henri Barbusse, winner of the Prix Goncourt in 1916 for Le Feu and a founder of the Clarté movement.

[17]Le Matin, January 22, 1902, 2. A generation after Emile Gaboriau's Monsieur Lecoq (1869), Gaston Leroux relaunched the French detective novel with his character Joseph Rouletabille in Le mystère de la chambre jaune (1907).

[18] See Henri Mitterand, Zola: II, L'homme de ‘Germinal,' 1871– 1893 (Paris: Fayard, 2001), 720–32, and F. W. J. Hemmings, "Cry from the Pit," reprinted in in Harold Bloom, ed., Emile Zola (Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 2004), 15–36. Jules Verne had also spent a day at Anzin before writing Les Indes noires (Paris: J. Hetzel, 1877), his mining adventure set in Scotland. The illustrator of Les Indes noires, Jules Férat, later illustrated Germinal in an edition of 1885–86. Movie director Victorin Jasset had also filmed at Belgian mine locations in Charleroi for his interpretation of Germinal (Aux pays des ténèbres, 1912).

[19] Jan Veth, "Kunst: Fransche Schilders in deze Eeuw," De Nieuwe Gids 5:2 (1890), 326. Veth detected in the "eclectic" work of Bastien-Lepage the influence of photography and ranked the modest portraiture of Henri Fantin-Latour higher than that of the late painter so much admired by the Germans and the English. Veth is best known today for his cover design and portrait etching for the first edition of his friend Frederik van Eeden's classic tale De kleine Johannes(s'Gravenhage: Mouton, 1887).

[20] The Flemish author Georges Eekhoud, who wrote in French, won praise from Joris-Karl Huysmans and, with some reservations, from Zola for his first novel, Kees Doorik (1886); see Mirande Lucien, Eekhoud le rauque (Villeneuve d'Ascq [Nord]: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 1999), 75– 76. In 1899 Eekhoud published Escal-Vigor, the first gay novel in Belgian literature. The earliest naturalist writer in Flemish was Cyriel Buysse: De biezenstekker (The Bastard, 1894) first appeared in De Nieuwe Gids 5:2 (1890), 186–212. His play Het gezin Van Paemel (The Family Van Paemel) had its premiere at the Multatulikring in Ghent on January 25, 1903, using lay actors. Other Flemish writers – notably Stijn Streuvels in De Vlaaschard (The Flax Field, 1907) – contributed to the flowering of late naturalist literature in Dutch, marked, as was art, by an inclination toward symbolism.