The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Portraits, Landscapes, and Genre Scenes: New Discoveries in the 19th-Century Paintings Collection at Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York holds an extensive collection of art works and cultural artifacts that comprises over 10,000 objects in all media from all time periods and cultures. Columbia has been collecting art since its foundation as King’s College in 1754. Among the earliest items collected were silverware from King George II and portrait paintings of the first University presidents.[1] Although the trustees and administrators over time have commissioned works, such as public outdoor sculpture, more than 90% of the collection has been acquired as donations and bequests from students, alumni, faculty, administrators, trustees, artists, and the general public, for more than two-and-one-half centuries. The collection grew exponentially during the twentieth century, particularly around the time of Columbia’s bicentenary, when the University received a number of important gifts from major donors, including alumnus and engineer Edmund Astley Prentis, who donated numerous historical paintings to the collection; medical and pharmaceutical entrepreneur Arthur M. Sackler, who donated over 2,000 works of art representing the cultures of the Ancient Near East, China, and Korea; and Barnard College alumna and writer Ettie Stettheimer, who bequeathed the largest portion of paintings, drawings, sketchbooks, and papers by her artist-sister Florine Stettheimer.[2]

Around 1950, perhaps as a response to this growth in the collection, the University created the Committee on Art Properties, comprised of administrators and faculty appointed by the Provost as an advocacy and governance body. The committee appointed the first curator in the early 1960s, and it was at that time that accessioning and inventorying of the University’s art holdings began. Over time, a department called Art Properties would be created and staffed with a curator, an art handler, and an administrative assistant, and established as a special collection unit in the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library. This departmental structure and the committee remain in effect to this day.

The mission of the University art collection always has been educational programming and curricular integration, and by extension display and exhibition loans. Although the primary users historically have been the faculty and students in the Department of Art History and Archaeology and the School of the Arts, cross-disciplinary use of the collection has been encouraged since the beginning and numerous divisions across the University have worked with Art Properties to acquire and display works throughout the school. The on-campus installation program may seem disheartening to those who work in a traditional museum setting, where the concern is often more with preservation than with education. However, this program has served the needs of this University, where the undergraduate core curriculum was founded on the idea that students’ exposure to the display of works of art and cultural heritage on campus was part of a proper humanities education.

In today’s world, where digitization has democratized access to art through innumerable online image databases and aggregators, the experience of the authentic work through object-centered learning has become more critical than ever. Art Properties has been instrumental in encouraging the practice of engagement with works of art so that through close examination and proper handling students can learn about the materiality and presence of art objects and cultural artifacts. But art education also clearly needs digital surrogates to complement the learning experience. In support of this, Art Properties is gradually releasing images and metadata of works from the collection through a multi-pronged use of social media, blogs, webpages, and print and online publications.

In support of the mission of the University art collection, and to increase awareness and use of it on a global scale, this article in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide serves as an introduction to just a few of the nineteenth-century treasures in the Columbia University art collection stewarded by Art Properties. The works discussed here encompass the three general types of paintings common in Europe during the long nineteenth century: portraits, landscapes, and genre scenes. Long hidden and heretofore largely unknown, these objects now are newly researched for the purpose of spreading the word about this important collection and advancing its educational use globally.

Portraits: Lord Byron

The Columbia art collection includes over 1,000 paintings and of this number more than half are portraits. Although the majority of these depict American sitters, often with a connection to the University, the collection also holds about 100 portraits by British artists or depicting British sitters. Among these are paintings by significant artists such as William Beechey, John Hoppner, Joshua Reynolds, and George Romney. About 60 of the British portraits are part of the George A. Plimpton Collection, donated to Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library by Plimpton’s wife, Anne Hastings Plimpton, and their son, Dr. Calvin Plimpton. A publisher of textbooks, George Arthur Plimpton (1855–1936) was a bibliophile at heart and over the course of his life he amassed one of the largest collections of European and American arithmetic and grammar texts dating back to the medieval period.[3] His love of the written word and of education led him to collect portraits of British authors—novelists like Charles Dickens and philosophers like David Hume—all of which are now owned by Columbia.[4] Plimpton acquired many of his British portraits from the London-based bookseller and antiquarian Charles J. Sawyer. Their extant correspondence suggests that Sawyer acted in part as Plimpton’s dealer. He often bought pictures at auctions or estate sales, and then submitted photographs to Plimpton for his approval. Plimpton rarely rejected a prospective portrait unless he already owned one of the sitter.[5]

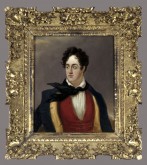

Among Plimpton’s treasured British portraits was a small picture of the Romantic poet George Gordon, 6th Baron Byron (1788–1824) (fig. 1). In a letter dated August 19, 1926, Sawyer sent Plimpton a photograph of the portrait and wrote: “This was sold as by Sir Thomas Lawrence; it is a charming study, full of colour, and I think might be attributed to one of Sir Thomas Lawrence’s pupils. It is a very pleasing painting, and I would like to send it for your approval.”[6] Plimpton purchased the picture for £35, and in his own notes listed it as by a follower of Lawrence. In 2004, however, this portrait was published in a guide to the special collection holdings at Columbia as by Lawrence himself.[7] In fact, research shows that there is no evidence Lawrence ever painted Byron’s portrait, as Lawrence reportedly told his nephew that he was once unable to meet Byron at an appointed time and they never rescheduled his sitting.[8]

Annette Peach, in her thorough study of portraits of Byron, has noted—based on the examination of an old black-and-white photographic reproduction and not the original painting—that the portrait derives from the 1807–9 painting of Byron by the Scottish miniaturist and marine painter George Sanders (1774–1846), today in the Royal Collection (fig. 2).[9] Measuring just over three feet in height, this painting depicts Byron having stepped from a boat and standing on the rocky shore of an unnamed lake. He is accompanied by his valet, usually identified as Robert Rushton. The wind blows Byron’s curls and his jacket is thrown open to reveal a tight waistcoat, as he stands with self-assurance on the shore in a pose reminiscent of classical sculpture.[10]

Sanders’s painting is important because it was the first portrait Byron commissioned of himself and dates from the publication of his earliest poems, when he was not yet world famous. The portrait was intended as a memento for his mother before he departed on his first trip abroad.[11] Byron, however, was dissatisfied with the representation, a sentiment he repeatedly expressed about all representations of him, as scholars have noted.[12] Although Sanders’s portrait was made early in Byron’s career and intended as a private picture, it came to be one of the most popular representations of Byron after his death, when his wind-swept hair and neckerchief became the hallmarks of the “Byronic hero.” Sanders’s whole-length portrait eventually passed to Byron’s friend Sir John Cam Hobhouse, who loaned it to be engraved for an 1830 biography of Byron.[13] Subsequently, in 1834, the head and torso of the portrait, without the landscape background, was used as the frontispiece to another book on Byron, Edward Finden’s Landscape and Portrait Illustrations of Lord Byron’s Life and Works (London, 1834; fig. 3). This frontispiece engraving is directly related to the Plimpton portrait of Byron owned by Columbia.

The facial features and the wind-swept hair, as well as the fashionable clothing and loose neckerchief blowing in the breeze, resemble the young poet as he appears in Sanders’s 1807–9 painting, but there are two notable differences. First, in the Columbia portrait, the waistcoat is orange-red and has two closed buttons at the bottom, while in Sanders’s painting it is blue and three closed buttons are visible.[14] Second, a dark threatening sky replaces the craggy rocks in the background of Sanders’s portrait. The Columbia portrait measures about 12 inches in height, which makes it approximately one-third the size of Sanders’s original painting. It would be tempting to claim this portrait was painted in 1834 by Sanders as an oil study for the published engraving, in part because the handling of the paint is strong and suggests a trained artist, but more likely it was executed by an unknown artist working from the engraving. Future scientific testing of the painting may lead to a more secure artistic attribution, but at least for now it can be determined that the portrait is in fact after Sanders and not by Lawrence or his followers.

Landscapes: Charles-François Daubigny[15]

Dr. Arthur M. Sackler (1913–87) is well known in museum circles as one of the most important twentieth-century collectors of Asian art. Columbia, among other institutions, benefited greatly from his generosity. But few know that, when Sackler began purchasing art around 1940, he collected nineteenth- and early twentieth-century art, including Barbizon and Impressionist paintings, and that he only made a switch to Asian art after 1950.[16] In 1970 Sackler purchased, then gave to the University, the painting The Sandpits near Valmondois (Les Sablières près de Valmondois) (fig. 4) by the landscape painter Charles-François Daubigny (1817–78), an artist associated with the plein-air painters of the Barbizon group and who early in his career often worked in the forest of Fontainebleau. Later, however, he was more attracted to and painted the banks of the rivers around Paris—the Seine, Oise, and Marne.

Signed and dated 1870 in the lower right corner, Daubigny’s painting depicts a scene near Valmondois, a village located approximately 23 miles (37 km) north-northeast of Paris on the Oise River. The painting conveys a sense of tranquility. Neither the river nor the trees move in the late afternoon sun. Our eye is drawn initially to the fisherman seated on the riverbank. His fishing pole points diagonally across the river toward a boat colored with a dab of red paint—perhaps an homage to John Constable, who is known for including accents of red in verdant landscapes. Further up the riverbank, above the head of the fisherman, one sees the sablière or sandpit and a sand barge, and to the left a series of houses that may be the village of Valmondois. Together, the sand pit and barge create a triangle with the fisherman and the boat, suggesting that at the heart of this tranquil scene is the juxtaposition of labor and leisure. Simon Kelly has noted that the Oise River valley became industrialized in the third quarter of the nineteenth century, but that Daubigny in his paintings frequently “screened out these modern elements, presenting an idyllic vision of the river.”[17] In this landscape, Daubigny has not removed the industrial scene but minimized it, making it an unobtrusive detail in the background.

The Columbia picture has a strong provenance and is documented in Robert Hellebranth’s extensive catalogue of Daubigny’s paintings as work no. 175, although he did not record the painting as being in the collection at Columbia.[18] Sackler purchased the painting from the Stephen Hahn Gallery in New York in March 1970 under the title Boy Fishing at the River Oise. Earlier, in 1963, when it had been sold at Parke-Bernet Galleries as part of the estate of Edmund S. Burke, Jr. of Cleveland, its title was Landscape with Fisherman. Further documented provenance includes the dealers “Hellenberg Paris” and “Glaenzer Paris,” the former probably either Ignace or his father Sigmund Hellenberg, and the latter Eugene Glaenzer, who had galleries in Paris and New York.[19] In addition, a fragment of a label on the stretcher names Georges Petit, the turn-of-the-century Paris art dealer.

Hellebranth has identified ten different paintings either entitled Les Sablières près de Valmondois or referencing this scene in the title, each of which varies in size and ranges in date from 1863 to 1877.[20] According to Hellebranth’s research, the painting now owned by Columbia is the largest depiction of this subject; it measures 30 5/8 x 57 1/8 in. (77.8 x 145 cm).[21] One of the smallest depictions, about one-fourth the size of the Columbia painting, is also the earliest: an oil study now in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 5). Signed and dated 1863, this work (Hellebranth no. 170) is noted in the Met’s online catalogue as a study for the painting now at Columbia.[22] The representations of the water, banks, and trees in these two works are similar, but in the Columbia painting the appearance of the fisherman and the additional trees on the right present a more harmonized and idyllic version of the landscape, reinforcing the artist’s interests in likely exhibiting and selling this painting. This is, then, an important reminder that, although Daubigny and his colleagues did paint works en plein air, they used those outdoor pictures as studies for large-scale, finished paintings produced at a later date in the comforts of their studio. While it is known that Daubigny spent parts of his childhood and the summers of 1845 and 1846 in Valmondois, in 1870 when he painted the Columbia picture he was living in Villerville in Normandy, then moved to London in October of that year to escape the Franco-Prussian War.[23] Daubigny thus painted this landscape in his studio, likely using the earlier study as a model.

Genre Scenes: Christian Sell

The third painting in the Columbia collection selected for discussion is Military Scene by the German artist Christian Sell (1831–83). It is an oil painting on panel measuring approximately 8 x 10 in. (20 x 27 cm), and is signed and dated 1882 in the lower left corner (fig. 6). The provenance of this painting is unknown. At a large university like Columbia, with more than 250 years of history, lack of documentation on the source of some objects is not unusual. While some art works officially were donated, others may have been left behind by faculty, administrators, or staff, and there is no way to trace for certain their provenance.[24] Notes in the curatorial file for Military Scene show that the picture was accessioned in August 1966; its source is listed as unknown.[25]

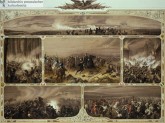

Sell is not well known today. Nevertheless, a survey of auction sales over recent decades reveals a consistently successful market for his pictures, suggesting a selected audience who appreciate depictions of costume subjects or genre scenes of officers and soldiers. Sell was born in Altona in the German state of Hamburg, which at that time was administratively governed by Denmark. He studied at the Kunstakademie of Düsseldorf and remained in that city where he had a successful career. The German artist and critic Friedrich Pecht considered Sell to be the leading military genre painter in Germany and noted that he “has made the life of the German soldier a part of himself.”[26] Sell’s most famous work was his large-scale painting The Battle of Königgrätz, July 3, 1866, which depicted the decisive battle during the Seven Weeks’ War that led to the Prussian victory over Austria.[27] This work also was distributed as a lithograph (fig. 7). Despite the reported success of this painting, Sell seems to have preferred painting cabinet-size pictures over large-scale history paintings. These smaller works were clearly geared toward middle-class collectors who took pride in Germany’s powerful military.

Sell’s painting in the Columbia collection shows three soldiers—one officer on horseback and two infantrymen—in a forest setting. The brown foliage suggests the scene is set in late autumn. The murky gray sky and the puddles and mud on the ground indicate the aftermath of a storm. The men appear to be on a scouting mission. The cavalry officer holds a pair of binoculars in his right hand, while the soldier whose back is turned to the viewer points toward the horizon, where faint traces of a village are visible. The second soldier turns to gaze in that direction, while the officer, about to halt his horse, also turns his head.

The two soldiers wear the dunkelblau (dark-blue) uniforms and spike-crowned helmets known as Pickelhauben associated with the Prussian infantry. The officer on the horse wears a peaked or forage cap and is dressed in the uniform of the Hussars, whose most noteworthy feature was the dolman jacket with intricate gold braiding.[28] His facial features bear some resemblance to those of Prince Friedrich Karl of Prussia (1828–85), whose uniform included a similar Hussar jacket (fig. 8). Victorious in both the Seven Weeks’ War and the Franco-Prussian War, Friedrich Karl was granted the title Generalfeldmarschall, one of the highest military rankings available to nobility. An earlier painting by Sell shows Friedrich Karl and his cousin, the Prussian Crown Prince Friedrich (later Emperor Friedrich III, 1831–88), on the battlefield during the Austro-Prussian War (fig. 9), and one can see again similarities in the facial features of Friedrich Karl, who is reading the map, and the officer in the Columbia painting.

Sell’s Military Scene, Daubigny’s Sandpits near Valmondois, and the portrait of Byron by an unknown painter, are just some of the many surprises found in the art collection of Columbia University, much of which is still waiting to be researched and published. The eventual online publication of this collection will no doubt bring many more surprises and will, perhaps, encourage other universities to begin to research and publicize their hidden collections of art and cultural heritage objects.

Roberto C. Ferrari, Ph.D.

Columbia University

rcf2123[at]columbia.edu

The section Portraits: Lord Byron is dedicated to my friends and colleagues Luca Caddia (Keats-Shelley House, Rome), who first helped direct my attention toward the artist George Sanders, and Carmen Ferreiro, whose own passion for Byron has been a source of inspiration in my own academic and literary endeavors.

[1] For recently published overviews on the art collection at Columbia, see Eve Glasberg, “From Buddhist Sculpture to Andy Warhol, Columbia Houses a Museum’s Worth of Cultural Treasures,” Columbia News, October 10, 2014, accessed September 8, 2015, http://news.columbia.edu/content/buddhist-sculpture-andy-warhol-columbia-houses-museum%E2%80%99s-worth-cultural-treasures; and Eve M. Kahn, “Raising the Profile of Columbia’s Art,” New York Times, January 8, 2015, accessed September 8, 2015, http://nyti.ms/1BNI9NM. For more information about the Columbia art collection, and to consult and research works of art in the collection, visit the Art Properties website, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, accessed September 8, 2015, http://library.columbia.edu/locations/avery/art-properties.html .

[2] On Prentis and some of his donations of art, see “Reminiscences of Edmund Astley Prentis and Katherine Prentis Murphy: Oral History, 1962,” transcript, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York. On Sackler and some of his donations of art, see Leopold Swergold, “New Light on Chinese Sculpture at Columbia University,” in Treasures Rediscovered: Chinese Stone Sculpture from the Sackler Collections at Columbia University, ed. Leopold Swergold (New York: Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University in the City of New York, 2008), 1–3. On works associated with the bequest of Ettie Stettheimer, see the Florine Stettheimer Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York. See also the curatorial files in Art Properties associated with individual art works donated by these individuals.

[3] For more on Plimpton and his book collections, see George Arthur Plimpton, A Collector’s Recollections, ed. Pauline Ames Plimpton (New York: Columbia University Libraries, 1993).

[4] The portrait of Dickens with his wife (2000.6.13) was painted by the American artist Benjamin Franklin Reinhart, and the portrait of Hume (2000.6.23) was attributed to Allan Ramsay, but new research shows that it is likely by David Martin, Ramsay’s pupil. Of the oil paintings in the Plimpton collection, about half are significant works dating from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries.

[5] Plimpton’s correspondence is part of both the George A. Plimpton Papers and the Plimpton Family Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

[6] Charles J. Sawyer to George A. Plimpton, August 19, 1926. George A. Plimpton Papers, Series VI: Collecting, 1693–1956, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. It is unknown where or how Sawyer acquired the painting.

[7] Jewels in Her Crown: Treasures from the Special Collections of Columbia’s Libraries (New York: Columbia University in the City of New York, 2004), 132–33.

[8] Kenneth Garlick, Sir Thomas Lawrence: A Complete Catalogue of the Oil Paintings (New York: New York University Press, 1989), 161. Sawyer’s and Plimpton’s belief that this picture was by a follower of Lawrence was probably due to the Regency-era clothing recognizable in Lawrence’s portraits.

[9] Annette Peach, “Portraits of Byron,” The 62nd Volume of the Walpole Society (2000), 1–144 [entry on Sanders’s painting: 27–32]. See also Christine Kenyon Jones, “Fantasy and Transfiguration: Byron and His Portraits,” in Byromania: Portraits of the Artist in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Culture, ed. Frances Wilson (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, and London: Macmillan Press, 1999), 109–36.

[10] Peach suggests that Byron’s pose is based on the Apollo Belvedere, but this seems unlikely. Byron’s head is turned the wrong way, and his arms are positioned differently from those of the statue. Byron does stand in contrapposto, however, so the pose is likely based on some classical prototype. Peach, “Portraits,” 28; and Annette Peach, “‘Famous in my time’: Publicization of Portraits of Byron during His Lifetime,” in Byron: The Image of the Poet, ed. Christine Kenyon Jones (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2008), 60.

[11] Peach, “Portraits,” 27–28.

[12] Byron suffered from fluctuating weight gain and loss, as well as lameness due to a right club foot. As a result it has been argued that he sought to control his public image to the point that he was accused by contemporaries of having created a public persona based on his own contrived poetic heroes, such as Childe Harold. For more on these portraits and their meaning for Byron, see Jones, “Fantasy and Transfiguration,” 109–36.

[13] Peach, “Portraits,” 27–28, 30.

[14] Peach notes that the extra open button was first apparent in the 1830 engraving, and that it “heightened the Byronic attitude of the sitter’s pose by leaving the waistcoat buttons undone.” Peach, “Portraits,” 27.

[15] My thanks to conservator Lenora Paglia, who undertook a recent cleaning and conservation of the Daubigny painting in the Columbia collection. Our engaging conversations about various matte and blanched patches in the painting’s surface suggest that a more in-depth study using X-ray and infrared technology might enhance our understanding of the artist’s technique and handling.

[16] Arthur M. Sackler Foundation, “The Arthur M. Sackler Collections,” accessed July 13, 2015, http://arthurmsacklerfdn.org/the-sackler-collection/.

[17] Simon Kelly and April M. Watson, Impressionist France: Visions of Nation from Le Gray to Monet, exh. cat. (Saint Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum; Kansas City: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2013), 166.

[18] Robert Hellebranth, Charles-François Daubigny 1817–1878 (Morges: Matute, 1976), 65.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid., 63–67; and Robert Hellebranth and Anne Hellebranth, Charles-François Daubigny 1817–1878 (Supplément) (Morges: Matute, 1996), 28–32.

[21] Robert Hellebranth records the dimensions as 78 x 145 cm. Hellebranth, Daubigny, 65.

[22] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Charles-François Daubigny, Landscape on a River (64.149.7),” accessed July 13, 2016, http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/436081. The curators describe their painting online as a study for the painting formerly owned by Glaenzer, suggesting they too are unaware this is the same picture in the Columbia collection.

[23] Madeleine Fidell-Beaufort and Janine Bailly-Herzberg, Daubigny (Paris: Editions Geoffroy-Dechaume, 1973), 20–21, 24–25, 31, 45, and 66.

[24] In the 1960s, when the accessioning of the collection began, all works of art received prior to 1964 were given the accession number sequence C00.#, a system that would allow for future growth as new works were discovered, as was the case with the Sell painting, which was given the accession number C00.537. This C00.# sequence is still in use for those works and any other works that are discovered to have arrived in the collection prior to 1964. In contrast to that system, all new works of art added to the collection from 1964 to the present have been assigned the more common date-based accession number sequence.

[25] After being accessioned, the painting underwent conservation, even though the condition listed at that time was “excellent.” The painting had a subsequent cleaning and the gilt-wood frame was restored in 1985. The remnants of an old label appear on the back of the frame, reading “Herm. Schramm, / Vergolder / in Dusseldorf / [. . .]urhahn No. 38,” suggesting the name of the individual who may have made the original gilt-wood frame.

[26] Quoted in Catalogue of the Private Collection of Modern Paintings Belonging to Mr. William H. Shaw (New York: American Art Galleries, 1890), lot 136.

[27] This painting reportedly was installed at one time in the Berlin Nationalgalerie as part of a series of patriotic paintings associated with German unification. My attempts to determine its present location, including at the Alte and Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, have been unsuccessful. For more on this painting and others in association with the Nationalgalerie, see Françoise Forster-Hahn, “Constructing New Histories: Nationalism and Modernity in the Display of Art,” in Imagining Modern German Culture: 1889–1910, ed. Françoise Forster-Hahn, Studies in the History of Art 53, Symposium Papers 31 (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1996), 84.

[28] Sell depicts a sash running across the Hussar’s chest from his right shoulder down to his left side, which contrasts with most representations of German Hussars, whose sashes run from their left shoulders down to their right sides. Considering Sell’s attention to detail in his painting of German military uniforms, this discrepancy seems odd and suggests a potential reliance on prints or other sources that may have inadvertently published such an image in this manner. For more on German military uniforms of this time, see Jan K. Kube, Militaria: A Study of German Helmets & Uniforms 1729–1918, trans. Edward Force (West Chester, PA: Schiffer, 1990); and Thomas N. G. Stubbs, Imperial German Military Officers’ Helmets & Head Dress 1871–1918 (Atglen: Schiffer, 2004).