The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

The Peredvizhniki: Pioneers of Russian Painting

The National Museum, Stockholm Sweden

September 29, 2011 – January 22, 2012

Kunstsammlung Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Germany

February 26, 2012 – May 28, 2012

Catalogue:

The Peredvizhniki: Pioneers of Russian Painting.

Edited by David Jackson and Per Hedström.

Stockholm: Nationalmuseum and Elanders Falth & Hassler, Varnamo 2011.

303 pp; color illustrations.

$89.95 (hardcover)

ISBN: 9789171008312 (English)

ISBN: 9789171008305 (Swedish)

On November 9, 1863 art students protested against the subject prescribed for the annual Gold Medal painting competition at the Imperial Art Academy in St Petersburg, Russia; as a result, fourteen of the best artists left the school.[1] Among them were Ivan Kramskoy, Konstantin Makovsky, Aleksej Korzukhin, and Nikoaj Shustov. Those who remained behind did so in order to pursue the goal of receiving the Gold Medal, the highest academic award for young artists in imperial Russia. In addition to the medal, the winning recipient was granted an opportunity to study in Italy for up to three years. During this period, he was obliged to complete a large work on a biblical or allegorical subject, to establish himself in the Italian salons, and hopefully, to obtain portrait commissions from the Italian and Russian aristocrats living in Rome. The Academy urged its protégés to uphold the classical tradition by concentrating on the Italian Renaissance artists and refrain from innovations.

In contrast, the artists who left the Academy in the wake of the revolt sought to paint the daily life of the Russian people. Like the Realists in France and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in Britain, this progressive group in St. Petersburg rejected both the academic conventions of the past and the sentimental genre styles of earlier generations. After leaving the Academy, they formed an artists’s cooperative society, and in 1870, they organized the Society for Traveling Art Exhibitions, which allowed them to promote traveling shows of their work. As a result, the painters themselves became known as the Peredvizhniki, or Wanderers. Last September, the National Museum in Stockholm opened a major retrospective exhibition of the Peredvizhniki, focusing on the diversity among the members of the group, and introducing western viewers to some of these artists for the first time.

The exhibition was organized by Per Hedström, curator at the National Museum, Stockholm, and David Jackson from the University of Leeds in the UK. Within a largely chronological and thematic structure, the exhibition looked at a variety of artists from the last three decades of the nineteenth century (fig. 1). The exhibition is the first to address the full variety of different kinds of relationships between the nineteenth century Russian artistic climate and society. While inviting us to contemplate the artistic production of these Wanderers, the exhibition of The Peredvizhniki: Pioneers of Russian Painting manages to assert the considerable authority of this group within the context of late-nineteenth-century Russian art. For anyone who has ever had trouble appreciating Russian Realist art, it is hard to think of a course of action more likely to clarify its virtues than a thorough immersion in the paintings themselves. We have grown accustomed to seeing Vasilii Polenov in association with the international expositions in Paris, Berlin, and Munich; or even Mikhail Nesterov and Valentin Serov in conjunction with the young artists around the St Petersburg journal Mir Iskusstva (World of Art). But their triumphant originality emerges all the more vividly when they are placed beside their forerunners like Nikolai Ge, Mikhail Klodt, or Ivan Kramskoy. Viewing the diversity of the Peredvizhniki oeuvre adjacent to their followers, such as Abram Arkhipov and Anders Zorn, allows the visitor to appreciate not only the breadth of the Peredvizhnki influence, but also the degree to which their art has been marginalized. The last major exhibition on Russian Realism was in the fall of 1990 when the Dallas Museum of Art, in cooperation with the Ministry of Culture of the USSR, presented An Exhibition from the Soviet Union. The exhibition at Sweden’s National Museum was perhaps the most detailed and unbiased project to date, aiming to present every artist of the group. It did what exhibitions so frequently promise, but rarely achieve: it inspired us to reassemble the landscape.

When it comes to Russian nineteenth-century art, the Peredvizhnki is a reasonably familiar subject, but not the reviews of their traveling exhibitions, and even less so their writings. Because the examples of their art are difficult to find outside Russia, and the non-Russian publications were sparse until recently, their art has been sporadically studied.[2] Various strategies have been employed to counter the resulting simplistic perception of the Peredvizhniki’s art and its socio-historical context. Among these is the examination of such art with respect to its functional role within Russian artistic politics and religion. Such an analysis emphasizes the social context for the production and reception of the imagery. The art of the Peredvizhniki, with its critical realist presentation, seems to have encouraged an emotional response from the public. The influential art critic, Vladimir Stassov (1824–1906), documented the public reaction to the Peredvizhniki images:

I am not talking here about a painter or his art, nor about whether he is a great master or to be properly contrived; but quite simply about every individual going up to a canvas and seeing it as something where he is master and judge, where he observes his own world, his own life, and where he can see what he himself knows, thinks and feels. This alone is genuine art, where people feel comfortable and actively involved; for art should respond only to real feelings and ideas, and should not be served up like some tasty dessert one can well do without. And yes, now we do have such art, authentic, genuine and not trivial; it has arrived, of course, after long years of scarcity, pretense, and imitation….[3]

Such a strong reaction seems barely credible to those of us trained to see the realist art as a mere depiction of different life situations and pertaining only to careful descriptions of everyday life.

Himself an ardent Russophile (“I am for a national art”), the artist Ivan Kramskoy (1837–87) believed that “art can only be national. In his 1880 statement, Fate of Russian Art, he wrote: “There has never been any other kind of art anywhere, and if a so-called universal art exists, it s only because it was the expression of a given nation at the forefront of world development. And some day, in the distant future, Russia will be called upon to occupy such a position strong nations, then Russian art, deeply national as it is, will become universal.”[4] It should also be pointed out that it has taken a century for nineteenth-century Russian Realist art to emerge from the shadow to which succeeding generations consigned it. The early-twentieth-century critic, Igor Grabar, condemned it in his analysis of Russian art as the most formal reincarnation of the Russian spirit.[5] The avant-garde artists accused it of a vulgar nationalism. Even the closely associated Soviet school of social realists tried to overshadow their forebears. Nonetheless, Ivan Kramskoy, Isaak Levitan, Vasili Perov, Ivan Shishkin, Nikolai Kasatkin, and Mikhail Yaroshenko must be seen as the founding fathers of the Russian Realist tradition.

The rise of the new school of Realism represented the most serious threat to Russia's mid-nineteenth-century art scene. At the heart of the Peredvizhniki'sreforms was the idea of creating a nationally representative and accessible art. Russian national identity had been subsumed in the Russian Empire since the time of Peter the Great, and later, it was submerged in the tyrannical principles of the nineteenth-century Tsarist regime. From the late eighteenth century onwards, the formal academic school, influenced predominantly by the neoclassical tradition, dominated Russian art. For many decades, this became the country's artistic ideology, supplanting the akademicheskaya manera zhivopisi (academic painterly tradition) that had been a major feature of Russia’s nineteenth-century artistic culture.

The eminent historian of Russian nineteenth-century intellectual history, Sir Isaiah Berlin, has familiarized us with the virtues and failings of this culture: “These French inspired liberals and German inspired romantics were acutely conscious of the difference between justice and injustice, civilization and barbarism, but aware also that conditions were too difficult to alter, that they had too great a stake in the regime themselves, and that reform might bring the whole structure toppling down. Many adopted an easygoing quasi-Voltairean cynicism, subscribing to liberal principles but whipping their serfs.”[6]

This comment is meant to convey the information that the Peredvizhniki, acute accusers of the state from the outset, gave much thought to the ideological and social significance of their works. The group emerged from the conservative Imperial Russian Art Academy in St. Petersburg and seized possession of precious artistic assets, including the country's best artists of that time, and even threatened the primacy of the art state and the institution itself. Curators Per Hedstrom and David Jackson have no illusions about the great heritage of the Peredvizhniki: “Within its broad range of interests, it encompassed powerful depictions of contemporary poverty and imprisonment, the beauty and grandeur of the national landscape, portraits of cultural luminaries and its anonymous masses, Russian history, mythology and folklore.”[7] Among the many questions that concerned the curators, there is one in particular that stands out. Do human analysis, perception, and critical observation of history result in art? Are the experiences of people, and the relationships between what is out there and what one sees constants of human nature? If one looks at the works of the nineteenth-century Russian Realists, it is possible to discern more complex responses. They extracted from their distinctive attitude toward psychological rendering, a naturalist mise-en-scene, or a specific historical figure and event. The effect of these alterations is to heighten the emotional scenes, endorsing the whole with an infinite individuality.

Another important subject of this exhibition is nationalism. Exactly what the nineteenth century understood by the term "nationalism" is an interesting question. Several Russian nineteenth-century artists and thinkers (including philosophers Petr Chaadaev and Alexander Herzen, literary critics Vissarion Belinsky and Nikolay Chernyshevsky, art and music critic Vladimir Stasov, the composer Modest Mussorgsky, and the artist Ilya Repin) made striking references to the virtues of truth and the vices of imitation. By 'imitation’ they meant the devotion to certain key artistic achievements of western culture, which arose from a fascination with western art. Over the course of their existence, the Peredvizhniki launched an investigation into the relationship of art to the observation and perception of social reality. The themes presented in their art works, ranging from direct observations of Russian politics, Orthodoxy, the Tsarist regime, and modern art theories to more concrete reflections on social needs and artistic materials, came to permeate Russian views on the modern identity of art, and opened a completely new approach to how artists relate, think, or feel about what is around them.

After the suppression of the Decembrist revolt in 1825, the government of Nikolai I launched an increasingly severe regime. The rapid growth of the new political ideology of nationalism exacerbated the Russian position with regard to Enlightenment liberalism and Romantic vision. In these circumstances, art education became a battleground for nation-based analysis of the modern values and Russian supremacy (“Russian Idea”), advocated by the Slavophiles. Just as in England, France and Germany, nationalism was an important ingredient of nineteenth-century artistic debates; but the internal colonization of diverse linguistic and religious groups was a unique element of the modern experience in mid-nineteenth-century Russia. In as much as art was a vehicle for social consciousness and consensus, the attainment of this goal was torn apart by the diverse sources and methods available for its expression.

It becomes evident in this exhibition that throughout the last three decades of the nineteenth century, the Peredvizhniki expressed myriad outlooks, including inward romanticism as a reaction to life's prosaic side as well as an outward sense of social justice. In his critical review of the Sixth Traveling Art Exhibition at the Society for the Promotion of Art, A. V. Prakhov wrote:

Throw off the blindfold of ingrained artistic prejudice, open your eyes to the outside world, and you will be astounded by the untold wealth of all that is beautiful in life and nature. A simple, minor brushstroke which you earlier regarded with condescension, or even with disdain, as something for your aesthetic contrasts, will turn out to be so grandiose, so perfectly resolved and completed, that you will simply feel guilty and ashamed, and you will be disturbed not by the smallness of the brushstroke you have seen, or the figure from nature, but by a realization of our impotence when faced with the grandiose accomplishment that is this figure before you![8]

At the heart of the exhibition is Ilya Repin’s The Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870–73, The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg), which were displayed together with the artist’s drawing series for the same picture (figs. 2, 3). The figures in the Russian Museum version of the painting shown in this exhibition, which is universally considered the latest of the two, are slightly larger than those in the Museum of Russian Art in Kiev, as well as more dynamic and individualized. Repin’s tableaux is several years older than a less well known painterly sketch of the same subject made by Vasily Vereshchagin (1842–1904), an artist whose rebellious nature Repin much admired (fig. 4). In the summer of 1866 Vereshchagin traveled to his uncle’s estate on the river Shusha, witnessing the other sides of the idyllic Russian country life. The artist, who by all accounts only painted when he felt inclined to do so and was famously discourteous about the wishes of his patrons, portrayed the barbaric side of his countrymen. The rather choppy strokes, painted across the horizontal field to suggest its breadth and naturalistic scale, together with the direction of the burlaki, the barge-haulers on the Volga, were particularly notable in the work of Vereshchagin. Yet, it was Repin’s burlaki whom Stasov singled out because he [Repin] “dared to see and to put into his work that which is simple and true and which hundreds and thousands of people pass by without noticing” (fig. 5).[9]

A. V. Prakhov also saw the value of Repin’s image of Volga barge haulers, exclaiming in his ardent prose:

Our social genre has so far been much too close to literature, it said far too much, too earnestly, and portrayed things too inadequately. Like a newcomer just recently allowed full-fledged membership in society, it has itself become somewhat overwhelmed, confined to small-scale, minor themes and forms of expression, trying its utmost to intrigue, amuse or disturb with its modest tale. This trend must come to an end! [...] The end is here with the appearance of The Barge Haulers, where simple figures of our time, indeed from a most neglected social class, whom some consider the dregs of society and others, the very roots of that society, have been acknowledged and portrayed with such love, with such seriousness and reverence, that you would think that you were looking at figures from the greatest of religious legends.[10]

The works in the first gallery familiarize us with the historical background and the emergence of the Russian social debate in art as a new kind of phenomenon after the breakdown of the classical paradigm during the rule of Aleksandr I and Nikolai I (1812–56) By discussing the subject matter of Mikhail Klodt's In the Ploughed Field (1871, The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg) (fig. 6), Aleksei Korzukhin's Before Confession (1877, The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg) (fig. 7), Grigory Myasoyedov’s The Zemstvo Dines (1862, The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) (fig. 8), and Konstantin Savitsky’s Repair on the Railway (1874, The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) (fig. 9), the exhibition offers a somber reflection on the perplexing growth of the political, institutional, and individual battles, and the impact of the individual struggle over diverse and ideological subject matter and stylistic investigations.

The second gallery examines “the temperament of each artist” and individual artistic exploration through immersion in Russia's landscape. The development of the Peredvizhniki's works can be read as a history of those who chose to paint it. One of the most famous examples is Isaak Levitan's Vladimirka Road (1892, The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) an evocation of the heartfelt loneliness implied by the long road that the figures stand on, the way it recedes and disappears into the landscape, and the sense that a spirit of yearning has infused the whole, so as to meld the figures in mood with an expansive natural setting (fig. 10). This is done by means of coloring and densely charged brushwork, which is applied on top of finely executed paint in the form of harmonious, luminous patterning. Levitan was thirty-two years old when he painted Vladimirka Road. Thus, the young artist, in his anxiety to demonstrate his understanding of the current language of naturalistic representation, provides panoramic tableaux of its precepts. For a deeper understanding of Levitan’s naturalistic representation, it is worth returning to the works such as Silence, Spring, Flood Water, Golden Autumn, or The Birch Grove. After completing his studies at the Moscow School of Painting, he moved to the country, often spending time with Anton Chekhov at his Melikhovo estate. This becomes apparent when comparing Chekhov’s Smoke with Levitan’s Spring, Khotkovo (1880s). To a certain extent, Levitan has even surpassed his friend in the confidence with which he reveals a wide-angle format and natural detail in the dull spring day, which frames an uninspiring life. Levitan’s late landscapes rarely depict visions of a simple paradise, but often reminders of suffering and death.

The third gallery invites us to look upon Russian life as an inner space that exists amorphously in the unconscious until it is revealed as an image, which arouses moods, reactions, and sensations in the spectator. More complex situations are described in the works based on the themes of loss and rebirth. These themes run like a leitmotif through the Peredvizhniki's lives, and it provides a fascinating record of the development and fluctuations of their tastes and attitudes towards Russian reality. With their intense, and intensely mixed, sympathies for the men and women who spent their days at work in the fields and quarries, or building railroads, the genre works of Konstantin Savitsky (1844–1905) and Nikolai Kasatkin (1859–1930) convey the harshness of Russian life. In Savitsky’s Meeting the Icon (1878, The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), viewers witness the presentation a “black” Madonnaicon to a group of villagers who have walked some distance to pray before this cherished image (fig. 11).[11] The roadside display of the Madonna by church officials who are traveling the countryside underscores the illicit nature of this gathering; during this period, the presentation of icons either in public celebrations, parades, or wayside chapels was forbidden by Tsarist law. Savitsky’s painting thus challenges the authority of the state as well as illustrating the religious oppression of the people. Likewise, Nikolai Kasatkin’s painting, Poor People Collecting Coal in an Abandoned Pit (1894, The State Russian Museum, St.-Petersburg) reveals the misery, loneliness, and fear that engulfs the Russian worker in the wake of the powerful invasion of industry into the once pristine natural world of the provinces (fig. 12).

Sergei Svetoslavsky’s (1857–1931) depiction of a View from a Window of the Moscow School of Painting (1878, The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) produces a striking contrast with the rest of the true-to-life representatives of the lower middle-class (fig. 13). It is also a very beautiful depiction of a crisp and sunny winter day, punctuated by the onion-shaped domes of the Moscow churches seen partially from the window. Viewed in a Russian context, it might be reasonable to regard Svetoslavsky as belonging to the second generation of Realists. He was born in Kiev to a wealthy family, and left for Moscow in 1875 to take painting lessons at the Moscow School of Art, Sculpture, and Architecture (where he painted the picture). He studied with the renowned landscapists Vasily Perov, Aleksei Savrasov, and Vasily Polenov. These were painters who went through a Realism phase in their early works, and traveled extensively through Russia and Europe. In Svetoslavsky’s case, it was Central Asia where he headed after the Tovarishchestvo (the Peredvizhniki group) ceased to exist.

The last section of the exhibition emphasizes the eclectic and improvisatory character of Russian national thinking and Russian religious thinking. Here we learn from Mikhail Nesterov's spiritual ideas and ideals about the pervasive influence of Romanticism in the nineteenth century. Nesterov (1862–1942) himself belonged to a new wave of spiritual symbolists in Russian art: in the aftermath of the reformist art and social scene, the Russian Orthodox painters of the late nineteenth century sought new ways to reinforce the religious impact of their work. However, Nesterov’s painting focused on the calling of an absent God into the presence of the congregation. The central question of his serene and ephemeral works between 1886 and 1904 is whether the concept of the true presence of God could provide a paradigm for the definition of the concept of the image, as in The Vision of the Boy Bartholomew and The Taking of the Veil. Together with a group of monks, hermits, and recluses, he created the fragile but stoic figure of an iconic saint, the young Bartholomew. They were meant in part to offer people mental repose, images to dwell on, and to dwell in, at least for a while. Longing is still present, depicted not only by the gestures and emotions of the figures in the picture, but rather experienced in the very space of the painting. The viewer, rapt in concentration and full of yearning and expectation, travels psychologically further and further into the world of the picture. Nesterov’s landscapes are images of heavenly beauty, and yet some might think that they were born of the painter’s disgust for the evils of the earth. Certainly, his notes from these years are filled with anxious comments about the political turmoil that beset Russia and Europe.[12] Possibly, it was in a state of despair that Nesterov later turned to making pictures of a more perfect world, living through Russia’s Communist years.

There is fundamental problem, however, with restricting artistry to painting, either in the Peredvizhniki’s time or now. In the first place, the Peredvizhniki were also sculptors and draughtsman taught by the Russian art professors of the State Academy or at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. Secondly, there were, and are, other preserves of wit and invention that have belonged predominantly to the Realist tradition, with their own trends of apprenticeship and proficiency. These traditions have been relegated to the status of political protest rather than art. In their own ways, however, they have been just as essential, as artistic, as art itself.

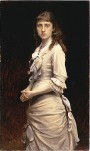

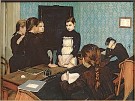

Painting may have been a largely male preserve in nineteenth-century Russia, but it was never exclusively so. Ivan Kramskoy taught his daughter, Sofia, how to paint alongside his sons, as did Vera Repin's successful father, Ilya. Kramskoy’s Portrait of the Artist’s Daughter Sofia offers viewers a glimpse of this relationship between father and daughter, showing Sofia in a straightforward manner so that her personality shines through as she gazes at her portraitist (fig. 14). The English-born Emily Shanks (known among the Peredvizhniki as Emiliya Yakovlevna Shanks) was the most talented among her eight artistic siblings. And when she, the most ambitions of them all, established her own independent studio in Moscow, she attracted the attention not just of the Peredvizhniki, but also the Empress who visited the 1891 exhibition where Shanks exhibited. The artist made no secret of her ambition: she was one of the first women admitted to the exclusive Moscow School of Art and the first full member of the Peredvizhniki since 1894; she took every possible advantage of this professional distinction. Rather than working on large canvases of mythological and allegorical subjects like the majority of her classmates, she worked on social themes. Her The New Girl at School (1892, The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) is a welcoming fresh feature in the exhibition (fig. 15).

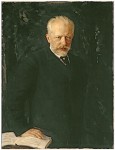

Although much of the Peredvizhnki work focuses on the larger social and political questions of the time, the exhibition also included a small number of portraits of figures, who are perceived as expressing a uniquely Russian cultural sensibility. Interestingly, two of these portraits also reflect the stylistic influence of late-nineteenth-century French painting. The dramatic portraits of two of the Russian composers from the Mighty Five group, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, are depicted not in a bland official style, but using thickly applied impasto brushwork that creates a feeling of emotional engagement. In Valentin Serov’s Portrait of the Composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1898, The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg) the composer is shown completely absorbed in his work, surrounded by manuscripts and musical scores, as he presumably plans out his next opera or symphony (fig. 16). Similarly, Nikolai Kuznetzov’s Potrait of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1893, The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow) carries an intensity that is hard to ignore (fig. 17). Kuznetzov has highlighted the composer’s head and hand, forcing the viewer to acknowledge Tchaikovsky’s almost confrontational scrutiny, as if he is challenging us to understand the music that lies beneath his hand in the lower left corner of the painting. Both of these paintings indicate an awareness of the expressionistic techniques being explored elsewhere in Europe in the 1890s, while simultaneously retaining the inherently Russian sensibility associated with the Peredvizhnki.

Unofficially, the Stockholm exhibition marks 140 years since the first exhibition of the Peredvizhnki, and reminds us that this Russian Realist art must be dealt with in the wider context of social issues. Despite its strict chronological limits, the show could only be a sprawling affair: the Peredvizhniki are more various than the rest of the Russia's artistic communities. Good spectators, or even just competent ones, will share the recognition that here we are especially close to the Peredvizhniki themselves. Moved as I always am by the pictures of sleeping children, the landscapes, the dramatic portraiture of the Russian composers, I find they speak to me far more of my relationships to my countrymen than any archival document, or history book ever does.

Dr. Inessa Kouteinikova

Independent scholar and curator, Amsterdam

inessa[at]xs4all.nl

[1] The prescribed subject was “The Entrance of Odin into Valhalla,” which seemed both fantastical and irrelevant to the lives of contemporary Russians.

[2] The pursuit of Russian national identity in art reached its apogee by the 1870s and was responsible, in part, for the rapid growth of the Russian collections. See Galina Sergeevna Churak, “Private Art Collecting in 19th Century Russia,” inThe Wanderers: Masters of 19th-Century Russian Painting: An Exhibition from the Soviet Union(Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art, 1990), 61. I owe this information to the kindness of Dr. Churak as well as the informative study by Rosalind Gray, “The Golitsyn and Kushelev-Bezborodko Collections and Their Role in the Evolution of Public Galleries in Russia,” Oxford Slavonic Papers, NS vol. 31 (1998): 51–67. See also recent publications on Russian realist art, including Elizabeth Kridl Valkenier, The Wanderers: Masters of 19th-century Russian Painting: An Exhibition from the Soviet Union (Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art, 1990), and her study, Ilya Repin and The World of Russian Art (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990); Art and Culture in Nineteenth-century Russia, ed. Theofanis George Stavrou (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1983); and David Jackson, The Wanderers and Critical Realism in Nineteenth-century Russian Painting (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2006).

[3] Vladimir V. Stasov, Selected Works, vol. 1 (Moscow-Leningrad, 1950), 45–46.

[4] Ivan Nikolaevich Kramskoy, Kramskoy on Art (Leningrad: Chudoznik RSFSR, 1989), 40.

[5] Igor Grabar, Starye Gody [The Past Years], July–September, 1912. See also Igor Grabar, V. Lazarev, and V. Kemenov, eds., Istoriya Russkogo Iskusstva, 13 vols (Moscow, 1953–69).

[6] Isaiah Berlin, Russian Thinkers, eds., Henry Hardy and Aileen Kelly (London: Penguin Books, 1978), 118.

[7] David Jackson and Per Hedstrom, eds., The Peredvizhniki: Pioneers of Russian Painting, exh. cat. (Stockholm: Nationalmuseum and Elanders Falth & Hassler, Varnamo, 2011), 36.

[8] See A. V. Prakhov’s review of the Sixth Traveling Art Exhibition at the Society for the Promotion of Art, in Russian Progressive Art Criticism of the 19th and early 20th centuries: A Reader (Moscow, 1977), 363–64.

[9] Vladimir Stasov, Kartina Repina Burlaki na Volge (St. Peterburgskie Vedomosti, 1873), Izbrannoe (Moscow-Leningrad, 1950), I, 67.

[10] See A. V. Prakhov, Sixth Traveling Art Exhibition at the Society for the Promotion of Art, 363–64.

[11] The “black” Madonna images, whether icons, paintings, or sculpture, are especially revered because some of them are believed to possess miraculous powers. It is important to note that “black” refers only to the color of the image rather than to the Madonna’s ethnicity, especially in European regions.

[12] Mikhail Nesterov, Davnie Dni (The Long Gone Days) (Moscow-Leningrad, 1959), 115.