Kingscote’s Dining Room and the Multisensorial Interior in the Late Nineteenth Century

by Lea C. StephensonLea C. Stephenson is a PhD student in art history at the University of Delaware. Her work focuses on late nineteenth-century American and British art, specifically the Gilded Age and the relationship between the senses, embodiment, and portraiture. Her current projects explore late nineteenth-century Egyptomania and the relationship between American Orientalism and racial ideologies. She received her MA from the Williams College Graduate Program in the History of Art in 2017. Stephenson has also previously worked at the Preservation Society of Newport County, Dallas Museum of Art, and the Clark Art Institute.

Email the author: lcsteph[at]udel.edu

Citation: Lea C. Stephenson, “Kingscote’s Dining Room and the Multisensorial Interior in the Late Nineteenth Century,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 20, no. 2 (Summer 2021), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2021.20.2.3.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Scholarly Essay|Project Narrative

Note: Mouseover or touch plan to highlight rooms. Click a room to select it.

Fig. 1, Wrenda E. Bush (draftsperson), First-floor plan, Kingscote, from Historic American Buildings Survey, 1969. Drawing. Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington. Image in the public domain; available from: Wikipedia.

Upon entering Kingscote, their residence in Newport, Rhode Island, the King family and their guests followed a succession of spaces leading into the dining room, a spectacular space designed by McKim, Mead & White in the early 1880s. The entry hall, lined with prints and rich mahogany panels (figs. 1, 2), allowed a moment of pause before they continued through a low doorframe into an adjoining hall decorated with luminous leaded-glass transoms designed to look like flower boxes (fig. 3). A mahogany screen with intricate, Islamic-inspired patterns divided the space between the hall and the dining room. Yet, it was not until passing through the entry point of this screen that family members, and their guests, would be struck by the atmospheric, multisensory character of this 1881 dining room (fig. 4). Light would have danced across surfaces and caught the edges of the mahogany paneling lining the walls. A multitude of textures would have enveloped the dweller—polished wood, taut leather cushions, glowing Siena marble, and reflective celadon tiles. And, perhaps, a visitor might pick up on the hint of scent from dishes laid out across the sideboard or flowers from the arrangements. Designers and clients, I argue, together created the Kingscote dining room not only to stimulate but also to educate the senses.

Previously, Gilded Age homes have been framed in relation to social rituals, and the precious objects within them have been regarded as reflections of wealth and conspicuous consumption. Thorstein Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions (1899), in which commodity value is entangled with the leisure class, has clouded alternative readings of Gilded Age spaces and generalized the United States’ late nineteenth-century upper-class residential interiors as associated primarily with economic value and evidence of opulence.[1] Veblen’s theory of conspicuous consumption disregards how dwellers perceived interiors and how individuals inhabited ambient environments, instead disparaging elite acquisition as simply financial gain or beautiful objects as signs of “pecuniary emulation.”[2] In other words, the objects serve as signs of wealth and are considered part of the competition among the wealthy class to assert status and surpass one another’s social ranking.

Recent essays on Gilded Age architecture and design continue to emphasize the class-conscious nature of an upper-class society reflected within the interior, often focusing on European precedents.[3] A key text remains Wayne Craven’s Gilded Mansions (2009), in which the author explores specific interiors by Richard Morris Hunt and McKim, Mead & White (including Kingscote’s dining room) in the context of the social history of the late nineteenth century.[4] The upper echelon in the United States, or America’s so-called aristocracy, used largely European architectural modes to signify status and expressed themselves through new types of rooms and decoration plans. Craven devotes a full section of the book to the ways that Newport, with its fashionable resort architecture, served as an expression of elite taste, chronicling the social gatherings within its cottages, including Kingscote. Other more contemporary scholars also discuss Kingscote and the dining room space as an example of McKim, Mead & White’s early experimental designs in architecture and interiors. The majority of these texts contextualize the dining room within the Aesthetic movement or surveys of Newport architecture, singling out Kingscote’s space as an example of modern design.[5]

Rather than understanding Kingscote’s dining room as simply a reflection of a family’s desire for material wealth, this article suggests a different interpretation based on the interior’s sensorial components. Studies of the senses in fields related to art history serve as methodological models for my own interpretation of the Kingscote dining room, which aims to understand how the dining room designers and family members were aware of the various senses stimulated in a single room.[6] Cultural historians and literary scholars have begun to consider bodily senses, including touch and smell, as valuable alternatives to sight and to examine their accompanying cultural values.[7] For example, Katharina Boehm’s edited volume Bodies and Things in Nineteenth-Century Literature and Culture (2012) explores the Victorian ideas of materiality and embodied experience with objects. As she explains, objects, or “things,” carry a subjective agency and produce intimate relationships with the beholder.[8] In her introduction, she points out the ways that materials act upon the self and sensory perception. Her analysis of the mutual impact of physical objects and dwellers has informed my understanding of the Kingscote dining room.[9] In this study, I regard objects as more than passive “things.” Likewise, my analysis considers the lived experience of a dining room, one constructed and designed by McKim, Mead & White, and how objects, or “things,” act on the beholder by exciting their senses of sight, touch, smell, taste, and hearing.[10]

This project examines the McKim, Mead & White dining room at Kingscote as a multisensorial space associated with the late nineteenth-century Aesthetic movement, which began in England and reached the United States by the 1870s.[11] Aesthetic-style interiors emphasized the individual beauty of each object and included an eclectic and international mixture of forms and decorative details elevated to purely aesthetic purposes. While this project acknowledges this interior space’s debt to the Aesthetic movement, it departs from the standard views of Kingscote, and late nineteenth-century Newport interiors more broadly, as a product of class-driven, Gilded Age social status. Instead, this article presents a new way of looking at these interiors as carefully and deliberately planned ambient spaces aimed at educating the senses and exerting a spiritual effect on the dweller and the visitor. I build upon preexisting studies of the senses in other related fields, including literature and cultural history, to discuss the appeal of not only sight but also other senses at Kingscote, employing the dining room as a case study.[12] In this article, I develop my argument by singling out the predominant senses stimulated in the dining room and connecting the objects in the room with each sense to suggest the impact on the King family members and their guests. Overall, this consideration of multiple senses together suggests a more holistic, multisensory experience of the space (fig. 5). Specifically, the body served as the site where all of the senses came together and culminated in a phenomenological experience. The room is filled with a variety of textures, surfaces, and materials that play off each other and create an “ambient interior” with a harmonious atmosphere that was believed to bestow deeper, spiritual values upon the interior and by extension the beholder.

Nineteenth-Century Education of the Senses and the Aesthetic Movement

During the Gilded Age in the United States, designers and tastemakers fabricated artistic interior spaces to instruct the senses in the ultimate pursuit of aesthetic pleasure. Every object and decorative detail had the potential to enhance the senses of the dweller. Nineteenth-century art critic Clarence Cook (1828–1900) touched upon this role of objects within a domestic interior in his seminal book The House Beautiful: Essays on Beds and Tables, Stools and Candlesticks (1878). Cook describes how “these objects . . . have a distinct use and value, as educators of certain senses—the sense of color, the sense of touch, the sense of sight.”[13] References to the cultivation of the senses appear in Cook’s illustrations of human-object interactions. Dwellers interact with their possessions and rearrange objects, as if modeling for readers the various modes of behavior or movements that inform sight and touch (figs. 6, 7). A woman studies a book surrounded by decorative bric-a-brac to be gazed upon; another touches a portière in the entryway. Cook’s illustrations visualize physical interaction with decorative ornament and reinforce his claim that objects can educate the senses through sight and touch. Likewise, the dining room at Kingscote provided a platform to stimulate sight, touch, smell, and hearing through a range of objects.

Specifically, the education of the senses was an important aspect of the Aesthetic movement in the United States. In the eighteenth century, sight had been the dominant sense for attaining knowledge but, by the 1880s, the five senses more broadly became associated with the pursuit not just of knowledge but of moral and spiritual values linked to principles of beauty.[14] In particular, critics associated with the Aesthetic movement, including Cook and his British contemporaries, art critics John Ruskin (1819–1900) and Walter Pater (1839–94), theorized the Aesthetic movement’s belief in improving one’s self by organizing the home around principles of beauty and its evocation of the spirit. Initially, the edifying role of decoration proposed by Cook built upon the aesthetic theories of Ruskin, in which he redirected attention toward decorative art and the moral properties of domestic décor.[15] When advocating truth to nature, Ruskin equated beauty and spirit, or a universe that reflected the divine value of beauty. For example, Candace Wheeler, a textile designer and partner of Associated Artists, incorporated this Aesthetic movement philosophy in her Catskill Mountain home with a motto inscribed on a frieze: “Who creates a home creates a potent spirit which in turn doth fashion him that fashioned. Who lives merrily he lives mightily withouted gladness availeth no treasure.”[16] Wheeler’s inscribed motto specifically references how a home fosters a “potent spirit”—an interior that directly affects, or “fashions,” the dweller and can impart spiritual values. Overall, the interaction with objects lent humans an awareness of the self in late nineteenth-century interiors, as suggested by writings in art journals, articles on “home living,” or descriptions of possessions.[17]

Cook emerges as a key theorist of the Aesthetic movement in the United States in advocating the senses to elevate the material world and the moral and spiritual dimension. The House Beautiful and Cook’s reference to objects as “educators of certain senses” is tied to his overarching definitions of taste and his larger theoretical position on the importance of furnishings and decoration as essential to the cultivation of the self. One of the main goals of his book included the improvement of public taste: essentially the need for the United States to become familiar with the “beautiful” through décor and by living with objects.[18] Throughout Cook’s text, he provides instructions on “how we ought to live externally,” focusing on comfort, suitability, and sincerity to the individual’s taste.[19] Cook’s larger hope of improving taste for late nineteenth-century dwellers included emphasizing the need for individuals to consult their own desires, rather than owners simply acquiring expensive items for the sake of fashion. Moreover, his stress on “use value” when discussing interior spaces suggests the importance of physically interacting with one’s furniture in an agreeable way so as not to sacrifice comfort. In addition, Cook references ornament, including casts, pictures, and engravings, as one of the “chief nourishers of life’s feast.”[20] Objects and décor are intended to “nourish” the soul and enlighten the dweller’s existence in the room according to Aesthetic movement principles.

According to Cook, decoration is no mere matter, but rather a means of improving the soul requiring serious reflection. The epigraph of The House Beautiful—Ralph Waldo Emerson’s poem “Art”—is an allusion to the spiritual side of living with beauty. The last stanza of the poem references the “privilege of Art,” with the following lines reaching an “upper life the slender rill / Of human sense doth overfill.”[21] In other words, Cook’s connection between transcendentalism and late nineteenth-century interior decoration foregrounds the idea of living within an artful interior to attain a higher spiritual state, similar to communing with nature to reach God. A reference to the individual or, as Cook describes, “putting a soul into a room,” suggests moving the material world to a spiritual realm.[22] These interactions, it was believed, could lead to higher spiritual truths when in harmony with art.

Aesthetic movement theorists and practitioners believed that domestic spaces had the potential to “fashion” and educate those who lived in them, akin to objects exerting an agency upon the self. When Cook mentions “education,” he initially places the term in relation to a catalogue of things in the living room, or “bric-a-brac.” Objects should be well chosen, whether according to beauty of form, color, or workmanship. He asserts that it is not necessary to have many objects “within reach of hands and eyes.”[23] Specifically, he incorporates the example of educating children with beautiful objects in the home, as in the case of a Japanese polished crystal sphere that could be handled and gazed upon by a child. In a discussion of mantelpieces, he again brings up the selection of objects: since the fireplace is the center of spiritual and family life, it is important to choose beautiful objects for the mantel. These objects “should be things to lift us up, to feed thought and feelings, things we are willing to live with, to have our children grow up with, and that we never can become tired of, because they belong alike to nature and humanity.”[24] Cook even discusses dining rooms, arguing that these specific rooms “shall be decorated and furnished as to encourage the most cheerful and festive trains of thought, and the sunniest good nature.”[25] Objects and decoration are intended to enhance emotions, experiences of the home that arise from living in close proximity to the materials. According to Cook, bric-a-brac educates the senses with these “slight impressions,” and a beholder becomes enlightened by beauty.[26] Education and the elevation of the individual is not merely accomplished by learning principles in a classroom or by reading a book but is tied to actual experiences and the direct interaction with objects in the home.

Likewise, Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman in their text The Decoration of Houses (1897) remark on the education of the senses in the context of aesthetic taste and lessons in beauty. Though written after the creation of the Kingscote dining room, Wharton and Codman’s decoration theories mirror Cook’s points on cultivating a child’s taste in terms of objects and the arrangement of an interior. In a chapter on the decoration of nurseries and school rooms, the authors advocate tasteful objects in these rooms in order to educate their senses and foster a feeling for beauty, likened to a civic virtue. Artful domestic surroundings and objets d’art were intended to guide a child’s bodily interactions: “The possession of something valuable, that may not be knocked about, but must be handled with care and restored to its place after being looked at, will also cultivate in the child that habit of carefulness and order which may be defined as good manners toward inanimate objects.”[27] Wharton and Codman’s reference to pictures, ornaments, and furniture as a daily experience for children indicates that the ambient environment was intended to stimulate the senses and lead toward an appreciation of beauty.

Alongside the Aesthetic movement’s belief in the spiritual benefits of “beauty” in art circulating in the United States, beholders were inextricably tied to the objects and accompanying decorative materials when living with or arranging their collections. Arrangements and the multitude of surfaces or materials, like the Kingscote dining room pairings, would stimulate a range of sensorial responses.[28] As I will demonstrate in the remaining sections of this article, the Aesthetic movement’s practice of stimulating the senses through aesthetic selections and objects was taken up by Stanford White and the Kings in the design of the Kings’ Newport dining room. They created a space where bodily interaction with decorations and furnishings occurred not just through sight but also through smell, taste, touch, and hearing.

As noted above, the Kingscote dining room was conceived and built in the early 1880s, a time when designers and patrons were becoming passionate about interior decoration’s role in providing aesthetic pleasure and spiritual values in the domestic sphere (fig. 8).[29] This space is grounded in the principles of the Aesthetic movement. Every object should be regarded as a work of art, and the ensemble of objects should focus on the visual properties of color or juxtaposition of textures to prompt sensory effects.

A brief description of the dining room and its contents reveals how a diversity of architectural elements and furnishings are transformed into an aesthetic ensemble despite their disparate origins. The room’s key architectural details are the mahogany paneling lining the walls and the cornice continuing around the periphery as a framing accent. Looking upward, the ceiling is covered in cork tiles framed by mahogany trim, which complements the wood paneling and the dark-toned, polished woods of the furnishings, creating a rich luster throughout the room. Even the radiators, which should be simply utilitarian, match the patterns of the mahogany paneling and harmonize with the surrounding dark wood furnishings. The windows that curve around a section of the western side of the room, as well as the opalescent tiles framing the Siena marble fireplace, together bring light and color into a space dominated by dark-brown tones.

This space is filled with an ensemble of eclectic objects (figs. 9, 10, 11, 12). The selection includes the Newport mahogany dining table placed in the center and the American colonial revival built-in sideboard that dominates the left side of the room and upon which the family silver, made by the US company Gale & Harden from the mid-nineteenth century, is arranged. Additional dining furnishings continue on the left side of the space, including a mahogany side table with brass pulls in the corner—another eighteenth-century revival object—which probably originated from a Newport furniture maker. Along with the mahogany furnishings from Newport and the mix of both American colonial furniture and colonial revival décor are glass tiles manufactured in New York, English Jacobean oak chairs, a bronze Chinese temple bell, and a Spanish vargueno, or desk.[30] Furnishings include a mixture of purely decorative aesthetic objects, such as the pewter vessels lining the mantel, and those that also participate in the room’s dining function, most notably the mahogany table in the center.

The History of Kingscote and the Dining Room

Kingscote was part of a growing upper-class summer colony in Newport (fig. 13). The architect Richard Upjohn designed the house in the gothic revival style between 1839 and 1841 for the Southern planter George Noble Jones and his family.[31] It was sold to William Henry King of Newport in 1863. The King family had made its fortune through trade with China, specifically in the mercantile business. By the 1860s, after William suffered a mental collapse, the cottage entered into the guardianship of relatives. His nephew, David King Jr. (1839–90) took over Kingscote and his uncle’s estate by 1875. David, his wife, Ella Rives King (1851–1925), and their family used the house primarily as a summer residence (figs. 14, 15).[32]

Kingscote is associated with the initial stages of the development of Newport into a summer resort and continues to exist today as a historical house-museum. The cottage was located on the corner of Bowery Street and Bellevue Avenue, the fashionable thoroughfare of Newport. For a Newport resident or tourist walking down Bellevue, Kingscote was the first in a succession of elite private residences that could only be briefly glimpsed, as they were shielded by trees and set back from the street (fig. 16). The Kings lived in the house from May to November (relatively longer compared to other summer colonists who spent only a few months in Newport).[33]

Fig. 17, Richard Upjohn, Kingscote first- and second-floor plan, ca. 1840. Ink, graphite, and wash on paper. Upjohn Inventory, Avery Library, Columbia University, New York. Image courtesy of Jennifer Robinson.

Note: Mouseover or touch to highlight the McKim, Mead & White dining room on the floor plans.

Fig. 18, Comparison of Richard Upjohn, Kingscote first-floor plan, ca. 1840. Ink, graphite, and wash on paper. Upjohn Inventory, Avery Library, Columbia University, New York. Image courtesy of Jennifer Robinson. And Wrenda E. Bush (draftsperson), First-floor plan, Kingscote, from Historic American Buildings Survey, 1969. Drawing. Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington. Image in the public domain; available from: Wikipedia.

During the height of the summer season (July and August), life in Newport centered around social activities, which were mostly performed in the dining room. The King family, therefore, relied heavily on this room for entertaining and gatherings. In 1880, they hired the New York–based architectural firm McKim, Mead & White to build a dining room addition to the original cottage. For the project, the architects, who would eventually come to define the architectural style and opulent spaces of the American Renaissance in the form of estates and civic buildings, designed the eclectic dining room and adjoining hall, and moved the service wing and kitchen to make way for additional bedrooms upstairs (figs. 17, 18).[34] Within the context of the interior of the house, the new room existed alongside preexisting mid-nineteenth-century spaces and compact adjoining sections of the house. On the exterior, the architects included the addition alongside gothic revival gables and continued the preexisting slate-gray boards for the exterior, evidenced by the lapped shingles. In addition, they granted the dining room a degree of privacy by setting the space back from the street and away from public view. Upon entering the residence, guests would approach the dining room through the adjoining hall.[35]

In contrast to the grander Newport mansions that line Bellevue Avenue, which have several rooms reserved for different meals, Kingscote was considered a smaller cottage with a single dining space (fig. 19).[36] Family members would use the interior at specific times, as meals punctuated the day. The room also doubled as a ballroom space for hosting family celebrations, including coming-out parties and weddings (the room includes a removable screen so that the space could be expanded). For the Kings and their late nineteenth-century guests, Kingscote’s dining room interior visually embodied the Newport summer season and elite community. Summer cottages, by the 1880s, had begun transforming to suit the tastes of rising millionaires, becoming centers for fashionable society (figs. 20, 21). Kingscote’s location in a fashionable summer resort dictated how the dining room would be integrated into the larger social scene. A Newport residence was an essential part of a “see and be seen” culture. Though a dining room could convey to guests through sight a type of sophistication and cultivated taste in the selection of décor, the space would also impact additional senses as the guests and family members navigated the space.

On an early autumn night in 1881, David King noted in his diary that the family “inaugurated the new dining room.”[37] Dinner parties, like those hosted by the Kings, would be included in the season’s packed schedule, in addition to Bailey’s Beach and Newport Casino events. During the summer, dinners could be lengthy formal events with eight to twelve courses, lasting up to three hours. Hosts and guests settled into the dining room for the evening—plenty of time to absorb the ambiance and therefore educate the senses. Evenings began in the space and likely concluded in the nearby parlors (fig. 22). Specifically, the Kings belonged to an exclusive set as members of “old money” rather than the incoming nouveaux riches of the summer group. Their guests included “old” New York families, such as the Astors and Goelets, as well as the young author Edith Wharton.[38] Yet the Kings’ dinners were always attended by no more than fifteen guests, due to the smaller scale of the room (fig. 23). Compared to other Newport formal dining in grand halls, for example the Vanderbilt family’s Breakers interior designed in 1895, the Kings’ dinners were intimate gatherings. Guests would be immersed in the room. These smaller parties allowed their visitors to be aware, even sensitive, to the room’s details and surfaces.

For the Kingscote dining room, White worked closely with the Kings and collaborated with designers.[39] David King was close friends with White and would have been aware of, if not involved in, the décor in his dining room. Supposedly the two men, along with other New York artists, shared a “hideaway” in the Holbein Building in New York, which they referred to as “the Morgue.”[40] The Kings, therefore, were not clients divorced from the design process.[41] Instead, the dining room showcases David and Ella King’s willingness to select fashionable, up-to-date design. With this interior, it is difficult to untangle the influence of the architect-artist and the patrons, since White was drawing heavily upon the King family’s own collection of decorative objects and presumably on the designer and patron’s shared tastes.

In the firm of McKim, Mead & White, White is credited with carefully orchestrating the interiors, and the Kingscote dining room, with its variety of colors and textures and unity of form, exemplifies his aesthetic principles (fig. 24). According to one of White’s colleagues, “to White architecture meant color first, then form, texture, proportion and plan last of all.”[42] Because he was an architect, one might expect White to have prioritized the architectural layout but, instead, he focused on color, form, and texture, which are associated with sensuous effects, and the transformation of utilitarian things into an artistic ensemble.[43] Color and form would stimulate sight, while texture would best be understood through the active engagement with objects and the resulting, more intimate, sense of touch.

With his interior design, White set up his client’s “experience” of a room. He selected a wide range of materials to experiment with using different combinations, as exemplified by his treatment of the fireplace. The shiny pewter vessels on the mantelpiece are arranged against celadon tiles, with the glass mosaics of dahlias that trim the mantel catching the light (fig. 25). Another layer includes the mahogany band that runs across the Sienna marble fireplace. Brass sconces bring an element of light to the reflective framing of the brass around the hearth, which is completed with the organic decorative details of the mounts (fig. 26). Specifically, the architect was intrigued with methods to play up the visual effects of an interior and the role of sensuous objects (fig. 27).[44] At Kingscote, White focused on the aesthetic impact of “moments” across the space.

To help realize the carefully coordinated Aesthetic-movement dining room design and its multisensory effects, White hired contract artisans to complete the woodwork, marblework, glasswork, and hardware. The firm Mead and Taft completed woodwork, including the cherrywood floor, mahogany wainscoting, the carved screen, and sideboard.[45] J. F. Pahner and Son produced the tactile brass hardware with the ribbed edges, and Fisher and Bird supplied the Siena marble facings. White worked closely with designers and craftsmen, as seen in the repeated motifs throughout the room—the dahlia blooms on the windows correspond to the floral motifs on the Archer & Pancoast brass sconces on each wall. He likely designed patterns and then submitted ideas to the craftspeople, culminating in the coordinated natural and floral motifs across the room.[46]

In the Kingscote dining room, White combined his own designs with an eclectic array of objects that belonged to the Kings, mixing together American colonial revival, Islamic, and Japanese styles (fig. 28). White commissioned decorative details and objects like the built-in sideboard in the American colonial revival style and included them alongside an eighteenth-century cellaret owned by the King family; dining chairs based on colonial designs by the Newport cabinetmaker George E. Vernon & Co. acquired by David King (fig. 29); and an American colonial spinning wheel, a family heirloom that referenced the Kings’ family connection to the golden age of Newport during the eighteenth century and more broadly hinted at colonial life. In addition, White drew upon Islamic artistic traditions in designing the woven patterns of the screen and in his inclusion of key objects like the Kings’ Spanish vargueno, which the architect likely selected for its intricate, Islamic-influenced ebony-and-ivory inlayed design.[47] The influence of Japanese decoration appears in White’s choice of asymmetrical compositions and the natural, floral subjects of the leaded glass, and, significantly, in the architectural beams surrounding the room, which resemble the kamoi railing that frames traditional Japanese houses.[48] White’s Japanese-influenced architectural elements coexist with the assemblage of the King family’s Asian art objects. When David King Jr. moved into Kingscote in 1875, the cottage already included William Henry King’s collection of Asian objects from his years of involvement in the mercantile business within China. In addition, the Kings were probably fascinated with Japanese designs due not only to the family’s business connections in Asia but also to the popularity of Japanese art and culture in the United States at this time. David brought his own collection of Asian objects to join his uncle’s Chinese art, including a nineteenth-century teakwood familial shrine and a screen with panels embroidered in silk.[49]

In compact areas of the room, such as the far-right corner, where White brought together his own designs with the Kings’ possessions, he transformed the Kingscote dining room into a globalized interior. In this area of the room, a seventeenth-century Chinese bell appears in front of the Tiffany & Co. opalescent window tiles (fig. 30). As a final touch, White included the previously mentioned colonial spinning wheel taken from a family barn.[50] Such groupings offered juxtapositions and comparisons between the designs of different objects from around the world.[51] The transatlantic character of the interior was even mirrored in the Kings’ selection of servants and the laboring class of the summer resort.[52] Like many Gilded Age households in Newport, the family hired staff from Ireland, France, Germany, and the United States for the season. In other words, the dining room was managed by a transatlantic constellation of staff.

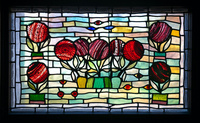

In addition, material dialogues appeared across the dining room to ignite a variety of sensory reactions and to create a unified, poetic effect that addressed different senses.[53] The term “poetic” suggests a type of rhythm and sound component, or an art with a formal logic.[54] A poetic sensibility informs the arrangement of objects and décor in the Kingscote dining room and serves as a means for training the beholder in the entangled poetry of the different senses. Woodwork, sinuous lines, or lighting effects in different sections of the room would call upon the King family and guests to study details with their eyes or handle the wood carvings. McKim, Mead & White repeated variations in textures, materials, and patterns in the space, including the mahogany trim on the wall paneling, which echoes the material of the central furnishings; reflective light between leaded-glass and metallic objects; and grid-like patterns on the original carpeting and in the arrangement of the glass bricks. Decorative elements responded to one another in the space, offering a mix of materials in conversation. Within the room, one decorative element included leaded-glass windows of dahlias designed by the New York glass firm D. Turno (figs. 31, 32). These windows mirrored the Japanese-style floral motifs in the brass sconces produced by Archer & Pancoast around the room (fig. 33). Despite the similarity in the floral designs, the materials—leaded glass and brass—presented differences in light effects. The dahlia windows tended to absorb light to create vibrant, red floral blooms, while gas lighting cast ambient reflections upon the metal sconces.

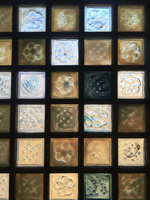

The room also included an array of woven grid patterns and other materials that mirror textiles, such as the Tiffany & Co. glass bricks bordering the fireplace. A late nineteenth-century photograph of the room taken shortly after the completion of the dining room showcases how the original carpet had a geometric grid pattern echoing that of the Tiffany & Co. tiles (fig. 8).[55] The pattern of the original carpet and the tiles would have also corresponded with the squares of colored glass in the windows, creating a visual continuity for the dweller seated in the dining room. The square-shaped cork tiles filled with a herringbone pattern on the ceiling and the cherry-strip flooring further the use of geometric patterns throughout the space. Square shapes in the cork tiles, flooring, wall paneling, and glass bricks create a repeated geometry throughout the space, amplifying its unity. Through sight and touch, family members and guests could track these material dialogues between objects. They could visually compare the forms of the room’s architectural elements and decorative objects, or its materiality through objects meant to be touched, like the turned spindles on the screen or the spinning wheel. The arrangement of the dining room encouraged them to make these material comparisons and to use their senses to interact with the objects in the dining space.

The remaining sections of this article will be structured around individual objects and how specific elements prompted sensations to educate principally the senses of sight and touch. Although the sensual experience of the King family cannot be replicated, I attempt to reconstruct how specific materials or objects might have stimulated the different senses of family members and visitors. Objects and decorative details highlight how certain points of the room, when paired with sensory effects, might have impacted the family members and guests. Similar to other “artistic” and ambient rooms of the era, Kingscote played with the effects of materials (fig. 34).[56] The Kingscote dining room, with its fusion of Eastern and Western motifs, transformed into a charged multisensorial environment.

The Dividing Screen: Combining the Senses

The room divider, essentially a single object, partitions the adjoining hall from the main dining area (figs. 35, 36). Made from mahogany, the screen could be removed to make additional space and signaled a dramatic entrance into the room—a marker of the dining space and a separator between the rest of the house and the dining room with its specific sensorial experiences. Designed by White in collaboration with Mead and Taft, the screen, as noted above, includes turned elements inspired by Newport’s colonial past, such as the band of acanthus leaves, floral roundels inspired by Renaissance decoration, and a woven pattern. The screen continues the “Japanesque” line from the kamoi beam, referencing the vertical architectural detail above Japanese sliding screens.[57] This decorative device also references the Islamic mashrabiya, an ornate exterior window enclosure with a carved latticework screen, a detail seen in other early McKim, Mead & White architectural spaces.

The divider marks the liminal stage in the education of the senses, experienced upon entering the dining room—a moment that involves both sight and touch. Initially, the screen engages sight by allowing light to penetrate from the dining room windows into the adjoining hall. The divider, with its range of carved and smooth polished surfaces, also encourages touch. Guests or family members would literally have to touch a section of the screen to open it on their way into the dining room. Above all, this design element creates a clear marker between adjoining spaces. Compared to a closed door, the screen at once divides and demarcates the boundaries of the dining space, while revealing a portion of the dining room before one enters. Moreover, the ease of transition through this decorative portal suggests a fluid transition into the room.

American architectural critic Mariana Griswold van Rensselaer discusses the simplicity of interior design within country houses and the ambient nature of rooms, like those of Kingscote:

Such rooms demand no covering-up to make them livable, no mass of bric-a-brac, no crowd of furnishings and shroud of hangings to make them lovely. In truth, one of their greatest virtues is that, to the eye of an intelligent owner, they absolutely prescribe that their contents shall be simple—so distinct and so distinctly simple is their own architectural expression . . . preserving to his summer home that effect of air and space and unencumbered lightness which is the artistic voicing of the very purpose of its existence.[58]

In her text, van Rensselaer suggests that seasonal residences should have an open quality and “unencumbered lightness.” This lightness and intimacy of the country residence appears in the form of the dining room’s transitional entrance, which encourages the fluidity between spaces and the permeation of light, from the exterior through the dining room and into the interior hall. If the divider portion remained open, the screen takes on a welcoming quality, inviting the guests into the center of the house and beckoning them with decorative details to view what lies beyond. When it was closed, the porous quality of the screen enabled viewers to look through the woven patterns and wooden spindles, even viewing the leaded-glass transoms between the intricate, carved paneling. Interior rooms are “interwoven” as one space leads into the next.[59] Light and air can pass through the divider; yet when it is shut and the family and guests are inside the dining room, it can also lend a sense of enclosure and intimacy to the space (fig. 37). During the Aesthetic movement, it became fashionable for dining room screens to be included in a room to create an open space or break up a room into intimate corners.[60] However, it was unusual for a screen like the one at Kingscote to occupy a large portion of a room.

The screen exemplifies the multisensory character of the room. In addition to engaging sight and touch, the screen also functions as an object that can enhance the experience of smell. Rather than completely separating the dining room from the remainder of the house, the screen has a porous quality that enabled scents to travel between the turned spindles and open spaces. Along with powerful food aromas, floral scents from the surrounding natural landscape could permeate the interior if the windows were open.[61] In at least one documented instance, the Kings perfumed the house with elaborate floral arrangements. In 1896, the coming-out ball for the Kings’ daughter, Gwendolen “Maud” King, was held in the dining room. Newspaper accounts emphasize the floral decorations covering the entire room provided by the famed florist, Hodgson:

looking to the north side of this new and artistic room the guest would discover there a treatment in aquatic flowers and one of the most beautiful variegated grasses, including the tall arundo-donax, grasses and plumes of the Japanese maize. . . . Among them were ten dozen bouquets of pink and white roses and lilies of the valley, also as many boutonnieres of jassamine [sic], roses and carnations . . . Up to the hour of the dance the bouquets were hanging by satin ribbons from the arms of especially designed devices which formed the decorative feature of that portion of the room. The musicians were partially concealed by a delicate screen of fern in an alcove just off the dancing floor. All around the room was a wainscoting nine feet high and a three-foot fringe of old gold brick on which were hung old Roman garlands of flowers.[62]

The newspaper description suggests that flowers, grasses, and ferns were used to create a verdant atmosphere in Kingscote’s space. This article also directs attention to how the family and guests might have experienced the variety of floral scents and how the floral decorations might have worked in harmony with the decorative details of the room. Specifically, the Kings hung bouquets on satin ribbons on the screen, likely fastening them to the turned elements or Islamic woven patterns. Guests would have physically interacted with the screen when picking up the floral bouquets. The screen, therefore, was a multisensory device. More than just a decorative divider, it allowed for the flow of air, light, and aromas, as well as haptic experiences.

Sight and Embodiment through Ambient Light Effects

Glass transmitted light into the dining room, affecting the experience of sight and perception in the room. In late nineteenth-century spaces, glass bricks and tiles were often made of dark tones of opaque glass that would reduce the amount of daylight permitted to enter the interior. Instead, White carefully selected a range of glass—clear, leaded, and opalescent—to stimulate dynamic reflections and produce both atmospheric warm and cool tones that covered the walls and reflected on the floor closest to the windows of the dining room (fig. 38). The main source of daylight comes from a row of three clear plate-glass windows that face the south onto the driveway and follow the curvilinear shape of the room. The clear glass allows the strong projection of natural light into the room during the day; gaslight from the brass sconces originally lit the space in the evening (fig. 39). White installed Tiffany & Co. opalescent glass tiles around the rectangular panes of clear glass. He continued the use of multicolored glass tiles in the smaller, rectangular windows above the clear panes and just below the ceiling, but there they surround the stylized glass dahlia blooms designed by the New York glass firm D. Turno to trim the upper portions of the room. The Tiffany & Co. opalescent glass tiles appear once again in a grid pattern that fills the window openings flanking the fireplace in the west side of the room (fig. 40). Covering large portions of the room, the glass-tiled walls transform into a haze of milky blue and cream tints. The tiles also include a variety of natural forms and geometric motifs pressed into the glass—petals, shells, and small circles. Specific tiles on the walls include asymmetrical Japanese floral motifs, which connect the room back to the natural world and underscore the international character of the room through Japanesque details. Each tile appears as an individual component within the variety of blue tints and wash of tones, transforming into abstract pools of color upon closer inspection (fig. 41). For the interior, the Kings relied heavily on ambient light from the opalescent tiles, or the dim glow of lamps playing off reflective accents and surfaces, to stimulate sight.

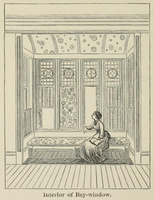

During the period of the Kingscote dining room installation, there was an increasing interest in stained glass for its aesthetic and sensual impact among designers in the United States. An 1878 home décor manual includes an illustration of a woman captivated by stained-glass transoms, the horizontal window over a door (fig. 42). Leaning upon the windowsill, she gazes up toward the transoms, as if mesmerized by the ensemble. The illustration captures how glass was placed in specific arrangements to augment the interior, even elicit a response from the dweller. Colored glass could cover surfaces with decoration or “gratify the eye with color.”[63]

Fig. 43, Details of D. Turno, Leaded-glass windows, Kingscote, 1881. Leaded glass. The Preservation Society of Newport County, Newport. Courtesy of The Preservation Society of Newport County.

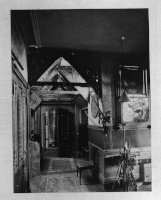

To coincide with the Aesthetic movement, stained-glass designers also began to emphasize the materiality of glass, as seen in the Kingscote windows (fig. 43). Artists began playing with the effects of glass and the natural transparency of the material. By experimenting with the textural effects of glass to add dimension, designers created jewel-like appearances with windows. Transparent glass (clear glass sheets with bubbles and streaks) caught the light. The Kingscote transoms are composed of antique glass with the subtle, irregular bubbles found across the grid background or green-tinted leaves. The uneven surface of the material absorbs the light and holds it, “giving out the rays from its innumerable inequalities as from the facets of a gem and producing a richness and brilliancy.”[64] For practical reasons, colored glass was meant to control the quality of light entering the room. It became fashionable to emit light through color and avoid the “glare of the white light of day.”[65] Contemporary examples of leaded-glass installations in interiors of the early 1880s included Louis C. Tiffany’s New York apartment hall (fig. 44).[66] In order to manipulate the light entering the gable, Tiffany installed windows in the passage that were raised by a large wheel and chain. During this period, glass designers like Tiffany considered the shifting character of natural light and consciously created light effects using colored and textured glass.

Colored glass played a key role in the domestic sphere in the United States during the late nineteenth century, and artists and critics began taking its effect on the viewer into account. Writer Mary Gay Humphreys discusses colored glass in an article published in the Decorator and Furnisher in 1881: “Color and light are the two great tonics of the body and feeling, and in glass we find them each enhancing the charm of the other.”[67] According to Humphreys, colored glass has a direct effect on the body, instilling a feeling of well-being. Nineteenth-century discussions on the effects of stained glass considered how methods of perception could be enhanced or altered. Leaded glass was used to create an enclosed, sensorial environment, as it greatly impacted the sense of sight or spatial orientation around the room. According to Leland Roth in his discussion of McKim, Mead & White’s Kingscote interior, “the expanse of the translucent glass and the shimmering, shifting colors create a sense of intimate enclosure and privacy, while opening up the wall to the sun at the same time.”[68] As described by Roth, the glass had a dual effect: both closing off and opening the interior to the exterior world, an effect similar to that of the dividing screen. The dahlia transoms and tiles intentionally block out views of the service wing, which projects from the western side of the residence.[69] The only view outside faces the picturesque driveway and tree line (fig. 45).[70] In addition, the wall of glass bricks and decorative transoms focus attention on the room itself. Glass helps to control the experience of the space. Essentially, windows and light are staged to contribute to the multisensorial environment, impacting the dweller’s perception and sense of orientation in the interior.

At the time of the dining room addition, White was already well aware of the great potential that glass had in controlling light levels and, by extension, ambiance. He was involved in the Associated Artists’ creation of the Veterans Room and library at the Seventh Regiment Armory (1879–81) in Manhattan (fig. 46). Associated Artists was a partnership of designers and artists, including Louis Comfort Tiffany, Candace Wheeler, Francis Millet, Samuel Colman, and George Henry Yewell. White would have been familiar with the group’s principles when he was pulled in as a consulting architect by Tiffany.[71] Associated Artists designed wallpapers, textiles, and furniture, drawing upon global sources and looking to glass or textiles from the United States to emphasize the variety of materials and craftsmanship in the creation of a space. Following Aesthetic movement principles, they combined Greek, Moresque, Celtic, Egyptian, Persian, and Japanese design sources into the Veterans Room. The space had a similar focus on ambient, sensorial qualities as the Kingscote dining room. Columns were wrapped in chains with studs of gold. Beams included silver stenciling. Portières were made with Japanese brocade and velvet appliqué, with the chain detail similar to armor. Furnishings were intricately carved and offset by the Tiffany opalescent glass, especially the blue tiles of the fireplace reminiscent of the glass found at Kingscote. William C. Brownell described this new type of interior design and ambiance for Scribner’s Monthly and emphasized the awareness of light on the part of the beholder: “When this has the benefit of a subdued light, a richness of effect becomes evident which, in the daytime, cannot be said to exist at all . . . and the twisted ironwork netting and doors fit happily into the sobriety of general effect so wholly dependent by day upon the rich mahogany of the book-cases.”[72] Brownell specifically points to the “rich” effects and altered light tones that served to enhance and bring out the decorative details of furnishings. The Veterans Room brought together a multitude of textiles, textures, and lighting for an overall encompassing effect.[73] Perhaps elite New York viewers would have seen the sensorial relationship to the Kings’ own dining room in Newport.

At Kingscote, White continued to rely on glass details to enliven visual experience through light and reflections, and he likely collaborated with Tiffany on the placement of the Tiffany & Co. tiles, which developed the sense of sight in the space (fig. 47). Every viewpoint from the dinner table includes a view of the leaded glass. The opalescent sections also coincide with the young architect’s interest in the ability of light to impact materials and textures across a room. When light is cast through the clear glass, reflective patterns from the Tiffany & Co. tiles appear on the floor (fig. 48). Gradations appear through the windows, impacting the ambiance of the room and how dwellers or guests would visualize the interior (fig. 49). When the Kings occupied the cottage during the height of the Newport season, the summer sun would be stronger, leading to stronger light cast across the tiles and absorbed by each tile.

Those dwelling in Kingscote would have interacted with colored glass on a daily basis—experiencing the gradations and brilliant effects of light as they changed throughout the day.[74] David King’s own diaries constantly record the weather outside: foggy or beautiful sunlight.[75] He was an owner aware of the atmosphere outside or shifting weather conditions and likely considered how they might impact the ambiance of his interiors. Luminosity varies across the dining room, and the effects change depending on the location within the space. The Kings used the interior at particular times of day, corresponding to meals and entertaining. In the case of meals and the room’s most active times, a Kingscote dinner often began at 8:00 p.m. and lasted until 11:30 p.m., from dusk into an increasingly subdued luminosity before being lit from inside.[76] The D. Turno dahlia leaded-glass transoms absorb light in the upper portion of the room with their warm tints. With the deep-red tones of the floral blooms, the light has a vibrant richness.

Yet, it is principally the Tiffany opalescent tiles, facing the southwest, that create the greatest change throughout the day in the room. White and Tiffany likely took into account the orientation of the room, as well as the more dynamic shifts in light in the southwest direction. By mid-morning, the opalescent glass begins to warm in tone (fig. 50). Large windows cast light across the southern wall and hit the Tiffany tiles. Bricks block out the majority of natural light, creating an ambient glow around the fireplace. Daylight is reflected against the glass or absorbed, depending on the specific location of the window. As seen in a Decorator and Furnisher illustration, nineteenth-century designers and dwellers considered this shifting, natural light (fig. 51). A stained-glass window on the stairwell creates an atmospheric layer of pattern on pattern once light casts a shadow upon the wallpaper. In a similar fashion, the Tiffany tiles pick up different shades depending on the time of day and the weather. Ultimately, Kingscote’s windows take on a dynamic quality with constant shifts and variations of warm to cool tones.

Note: Click to show/hide: Key meal times for the Kingscote family highlighted.

Fig. 52, Photo grid with Tiffany & Co. glass tiles in dining room, Kingscote, 1881. Opalescent glass. The Preservation Society of Newport County, Newport. Photographs by the author; photo grid by Allan McLeod.

As suggested by the “lightscape” of Tiffany & Co. tiles in the dining room above, the light effects of the opalescent tiles are constantly shifting and vary with each individual tile (fig. 52).[77] By mid-morning, the glass bricks start to warm up. Simultaneously, the natural light from the windows hit the leather chairs and pewter vessels along the mantel. Separate walls also interact differently with the natural light through the clear glass windows. On the right side of the room, the tiles seem to warm faster over the course of the afternoon, partly due to bushes outside blocking areas of the windows on the south side. In the early afternoon, reflections are less intense when the glass tiles absorb light. By the late afternoon on a sunny day, sunlight begins to spread over the floor on the southwestern portion of the room as the sun shifts to the west. Turning the corner into the dining room, the brightness of the Tiffany-tiled walls is even more startling. By the predinner hour for the King family, the light becomes subdued through the tiles, leaving only streaks of sun across the furnishings and glass. By the time of a late, summertime evening event in the late nineteenth century, the Tiffany & Co. tiles would only be illuminated by an artificial gas or electric interior light.

In the dining room, the Kings and their designers took advantage of the reflective surfaces as a means to stimulate sight (figs. 53, 54). The interior transformed with the dynamic light moving across objects, even bodies in the room, throughout the day and into the evening. Cook himself notes the decorative importance of the play of reflections within an interior. When discussing a sideboard designed by Cottier & Co., he remarks on its stylish simplicity and lack of excessive carving. Instead, objects placed upon the sideboard for special occasions, including fruit, glass, and silver, are “busy ‘making reflections’ on the gleaming surface for the benefit of those who have eyes!”[78] Light would be reflected, absorbed, or transmitted across different materials and textures in the interior.[79] As in Cook’s description, the silver objects on the sideboard at Kingscote reflect the sunlight in the room, offering glints of light in the dark sections of this piece of furniture. Reflected light also appears on the celadon tiles over the mantle, creating subtle changes in the tones over the fireplace. Designers took into account how the large brass sconces, decorated with Tiffany & Co. threaded glass and illuminated by gas light, would reflect onto their raised, shiny surfaces at night (fig. 55). In contrast, other furnishings, like the oak and mahogany chairs, absorb the warm tones of the light. Kingscote was not a static interior, but one that shifted with light changes and the movement of objects. As natural light transmitted through the glass and fell across the room, the Kings would have been enveloped in a play of leather upholstery, paneled walls, and reflective surfaces.

This interior, however, was an atmospheric space only reserved for the Newport summer season. The King family, returning to the summer colony from May to November, interacted with the interior during a limited time frame. The remainder of the year would include stays at their other residences in Washington, DC, and New York. Therefore, the dining area was a temporal, seasonally specific, ambient space. Decorative objects and light were only seen, or touched, at certain times of the year. During the remainder of the year, when the family retired from the house during the winter season, the room was shrouded in sheets by household staff.

Taste and Smell: Building an Ambiance

The Kingscote dining room was designed around the family’s meals and social events, both of which involve the senses of smell and taste (fig. 56). Although the role of smell and taste in the dining room remains speculative, this space, unlike others in the house, was meant to call upon the bodily senses when experiencing prepared food.[80] Smell and taste, unlike sight or touch, are also not linked materially to specific late nineteenth-century art forms or objects but are fleeting sensations. Above all, the dining room’s underlying purpose was for eating and gustatory stimulation. The kitchen and pantry were directly across from the room’s entrance, allowing easy access for serving meals. The Gale & Hayden tea service, seen in the ca. 1900 photograph of the room on top of the built-in sideboard, suggests the type of objects closely associated with taste (fig. 57; ). This tea service would likely be brought out for the Kings at specific times of the day, whether amid family members or entertaining guests. The service, including a coffee pot, tea pot, and sugar bowl, were associated with specific tastes and flavors, whether the sweet taste of sugar in hot beverages or bitter flavor of tea leaves. Objects and gustatory stimulation harmonize in the act of serving and taking tea.

Note: Click on the arrows in the lower left to advance the images or drag the images to move between views. Click the outlined details for more information about each object’s association with the senses and full-size images.

Gilded Age dinners were also largely elaborate banquet meals, and David King Jr. even recorded menus in his diary.[81] Mary Henderson, in her book Practical Cooking and Dinner Giving (1877), a guidance on meals and etiquette directed toward the upper class, describes how diners must taste a little portion of each dish due to the number of decadent courses.[82] Henderson also clarifies the proper silver or type of linen for hosting dinners and their prescribed movement across the table. Dining experiences and banquets were designed as an accumulation of sensual moments. Menus survive as mementos and souvenirs of this sensorial experience, specifically in the case of Gwendolyn King Armstrong’s September 1901 wedding breakfast held in the Kingscote dining room. The menu consisted of eight courses of French plates—fashionable for the elite—including “consumme [sic] en tasse” and “oeufs farcie en Bellevue,” followed by “poussins rotie au cresson.”[83] “Oeufs farcie en Bellevue,” or deviled eggs, refers to the Kingscote address on Bellevue Avenue, lending a regional emphasis to the dining experience, reinforced by seasonal ingredients on the breakfast menu that would have likely been sourced from nearby markets.

When the family actively used the room, scents from these dishes permeated the surroundings and the table settings (figs. 58, 59; ). In contrast to other domestic spaces, dining rooms were intended to welcome a variety of aromas entering the room, especially when the family used the space for meals. The built-in mahogany sideboard, a decorative element in the space, was connected to the sense of smell, as it was the location where a variety of dishes were laid out and served. With the succession of each course during a meal, the sideboard presented and introduced scents to the dining room and dweller. Though taste and smell are not explicitly discussed in nineteenth-century texts and documents on the dining room, these two ephemeral senses would have helped to build up an ambiance in the space. In addition, the senses of smell and taste located the dining room in the time and space of Newport. In addition to the seasonal and site-specific aromas that accompanied the food, the salty smell of the ocean, a feature of the summer in Newport, and the scent of the King family’s garden would enter the space through the windows.

Moreover, Kingscote’s dining room was an exceptional space for embracing smell—a sense largely neglected by late nineteenth-century audiences in the quest for ordered and sterilized environments. As cultural historians Constance Classen and David Howes explain, modern industrialization sought to deaden smells in favor of sight, but White and the Kings seem to have understood the importance of permeating scents in the dining room.[84] Urban environments emphasized sterile arrangements and cleanliness, which would be paired with deodorization into the twentieth century. Kingscote’s creation, therefore, coincided with industrialization’s shift away from scent in order to prioritize sight. Instead, White and the Kings embraced the evocation of aroma in the room by inserting floral or gustatory stimulations around the furnishings, rather than trying to mask their odor.

Kingscote’s room and its Newport location corresponded with writers like Oscar Wilde, who were becoming nostalgic for lost scents and in turn incorporated aromatic descriptions into their writings. The Newport landscape itself was involved in this sensorial revival in literature, which contextualizes the dining room’s creation. In George Lathrop’s novel Newport (1884), a sentimental view of the burgeoning summer colony with an array of social characters, the narrator describes the fragrances during a yacht outing: “the wind came from off the land, and poured around them in a breath of honey the mingled scent of flowers by thousands in the rich villa-gardens of Newport.”[85] For Lathrop, Newport was a setting to explore the evocative power of scents, which were also experienced in Kingscote.

However, how do these “aromatic” objects enhance the ambient nature of the room and pair with the senses of sight and touch? Scent could register, or record, a sense of place through an intimate, emotional experience—the smell of dishes or floral decorations from the family’s Newport greenhouse connected to a social event, for example. Classen, coming from the field of sensory studies, conducts a cultural analysis on aroma, describing how smell was connected to memory in the nineteenth century.[86] For example, a particular dish served in the interior could offer the dweller or guest a memory of the dining room, reminding them of their experience of this particular space.[87] Above all, aromas could be linked to the immediate surroundings of the dining room. Objects like the sideboard and the jardinière served to convey scent and taste and contributed to the idea of the dining room as an olfactory landscape.[88]

Touch and Sumptuous Textures

Precious objects worked together in the charged, intimate atmosphere of the dining room to create a play of textures and stimulate touch (fig. 60). The room’s designers and the Kings installed tactile surfaces across the room, driven by a variety of textures and, by extension, resulting in a range of physical sensations in the space. Family or guests often handled or used objects in this active, domestic space. Decorative furnishings were not meant to be catalogued as items in a collection but, instead, were to be used and arranged to create a strong physical tie between material and beholder in the midst of daily interactions.

Key objects, including the mahogany dining chairs, Spanish brass double brazier, and linen-damask tablecloth, were likely handled frequently in the space and provided unique tactile experiences. The George E. Vernon & Co. chairs had smooth, sleek, mahogany armrests (figs. 61, 62; ). Dwellers and guests could sit on the tufted leather cushions, press into the seats, lean on the mahogany back rests, and finger the smooth, rounded armrests during a meal. Installed by White near the fireplace of the dining room, the brazier, originally a container used to burn coal or wood, includes raised edges and motifs around the foliated sides to create an ornamental pattern with beveled edges (fig. 63). As a furnishing and decorative device in the room near the leather armchairs, the brazier would likely be handled by family members experiencing the curved edges and inlaid texture. Finally, the King family and guests would be constantly touching and physically interacting with objects on the dining table, including the woven linen-damask tablecloth (figs. 64, 65).[89] The cloth includes stylized patterns across the surface, which would have fallen across the table, touching the guests themselves or brushing against their hands during the meal.

Combinations of sensuous materials throughout the interior were meant to be touched and called for specific kinds of interactions, such as sitting on a chair or grazing one’s hand upon a fabric. In certain areas of the room, White and the Kings seem to have arranged items for their variety of textures and surfaces, available to the eyes and the hands. For example, White placed the raised edge of the brass brazier, with its beaded patterns, to highlight the duality of its smooth and rough surfaces, partnered alongside the nearby taut leather of the armchairs. An additional juxtaposition between a smooth and a rough, raised surface is the Tiffany & Co. tea caddy with the Japanesque design of the cherry blossom branches and bamboo (fig. 66). Placed on the dining room table or sideboard during tea time, the caddy, with its raised floral decoration, would have additionally spurred the sense of touch when it was handled, whether it was picked up or placed down upon the mahogany table.

Additionally, there was a particular spatial layout for the objects and tactile textures to promote physical interaction. For example, the George E. Vernon chairs were placed in the center of the room, as if initiating the subsequent tactile moments in the space. One sideboard displays the English silver, with its cold surfaces, and is positioned nearby the polished surface of the Siena-marble fireplace and upon the tight overlay of the geometric carpet. The tactile combinations continue with the dining table’s arrangement. Smooth porcelain rested on the rougher woven texture of the linen-damask tablecloth. Sets of mid-nineteenth-century Gale & Hayden silver with raised decorative floral patterns were arranged across the smooth mahogany table and sleek surface of the built-in sideboard.

Previously denigrated by art critics and philosophers with the rise of modernity, the sense of touch was imbued with new psychological and emotional resonances for nineteenth-century theorists.[90] The term haptic, the sense of touch, was coined during the mid-nineteenth century through experiments on the structure of skin in handling materials. Psychologist Alexander Bain, in The Senses and the Intellect (1855), reevaluated this formerly criticized bodily sense: “Touch is an intellectual sense of a far higher order than [taste or smell]. It is not merely a knowledge-giving sense, as they all are, but a source of ideas and conceptions of the kind that remain in the intellect and embrace the outer world.”[91] Increasingly during the nineteenth century, the “tactile” was believed to provide a deeper intellectual, not just a material, access to aesthetic beauty and spiritual values.

Nineteenth-century US writers also valued the sense of touch and alluded to the significance of the tactile appreciation of objects by collectors. American novelist Henry James developed a theory on “things” and the importance of interacting with the objects themselves, criticizing a collector who placed objects in a cabinet of collectibles to prevent them from being handled.[92] This theory also informs his novel The Spoils of Poynton (1897), which narrates the interaction between a collector, Mrs. Gereth, and her collection. Thomas J. Otten, in his article “The Spoils of Poynton and the Properties of Touch,” explores the intimate moments of touch in the novel, particularly the connection between bodies and objects within the context of interior decoration.[93] Otten points out the moments in the text when James focuses on the tactile, rather than sighted, relationships between people and objects. For example, Mrs. Gereth becomes distraught when giving up her beloved house, Poynton, and art collection to her son and his tasteless fiancée. Revolving around her adoration of objects and their closely associated spaces, James notes Gereth’s heightened sense of touch when assessing her possessions. She recounts: “Blindfolded in the dark, with a brush of a finger, I could tell one from another. They’re living things to me; they know me, they return the touch of my hand.”[94] Her elevated appreciation is through physical contact, and it is through touching her things that she knows them and that they make a direct impression on her.

Fig. 67, Details of objects in the dining room (Spanish double brazier, Minton yellow-ground cabinet plates, Samuel Jackson basin, Jacobean-style carved oak side chair, and sideboard hardware), Kingscote. The Preservation Society of Newport County, Newport. Images courtesy of the Preservation Society of Newport County and the author.

Gereth’s interactions with these objects demonstrates how the surfaces of objects were linked to the sense of touch during the nineteenth century. Their surfaces were seen as retaining the traces of the handwork of the individual maker, creating a connection between beholder and maker.[95] Likewise, tactile moments in the Kingscote dining room, such as holding items during a meal, the ritual of tea, or moving a decorative material when lifting an item, created a type of intimacy with an object and its maker. Touch could physically connect possessor and object, and even possessor and maker, in a direct, sensuous way. The surfaces of decorative objects were handled at specific points of the day or at social events (fig. 67). During mealtimes, for example, the mahogany chairs, linen tablecloth, and napkins were meant to be touched.

Domestic interiors, particularly the dining room, were designed around objects constantly being handled, repositioned, or taken in and out of rooms. Handling these objects arguably bestowed a type of tactile pleasure—one that created a physical impression when experiencing the room. These sensorial interactions with highly decorative, often also utilitarian objects had a cumulative impact, becoming a way to experience the room more intimately. As Classen describes, touch offers the possibility to “access interior truths” of objects rather than merely serving a functional purpose.[96] Likewise, handling objects within the dining room suggests the ability to educate a beholder about aesthetic beauty and impart spiritual values. At Kingscote, haptic behaviors and sensorial encounters were also entangled with a strict Gilded Age class stratum. The King family and their elite guests, the top tier of the upper-class community in Newport, had the freedom to interact with objects in an intimate manner in this process of educating the senses and the pursuit of physically handling beauty. The servant class would not necessarily be granted the same access to sit in the mahogany chairs and derive pleasure or knowledge from touching them but, rather, they would engage in a disciplined action, picking up silver services or cleaning surfaces before and after the dwellers and guests had used them.

Hearing and the Ambient Environment

Specific objects and decorative elements of the room design projected or regulated sound, the final sense attended to in the room. For example, White installed a seventeenth-century Chinese bell near dining accoutrements, such as serving dishes (fig. 68). If rung by a family member, the bell might trigger reverberations of sound throughout the room. Perhaps this bell, a sonic object, placed in a principal sight line for guests, was also meant to symbolically evoke sound when it was not in use.

Controlling sound in the room seems to have been a significant consideration for McKim, Mead & White. The ceiling consists of cork tiles, arranged to create a layered, herringbone pattern (fig. 69). The cork material would have absorbed noise, regulating and controlling the “sonic” nature of the dining room.[97] Conversations, sometimes in a variety of languages since the Kings often hosted diplomats and ambassadors, would have been dampened, so they wouldn’t carry into the adjoining spaces. These tiles also manipulated the sense of hearing by dulling noises and sounds, creating an intimate environment in the room by compressing the sounds from dining events into a single space. Compared to other nineteenth-century dining rooms, Kingscote stood out with this approach to the room’s acoustics, constructing an enclosed, multisensorial environment designed to deaden distracting, unwelcome noises arising from the nearby kitchen. Rather than a type of unregulated “sound,” noise would have been produced by regimented actions coinciding with the etiquette of the dining experience mixed with conversation.[98]

During the 1880s and 1890s, sound and the idea of training listening played an important role in culture and emphasized the inward character of Victorian audiences.[99] Family members and guests in the dining room would have been highly attuned to their own production of sound and the coinciding noises around the space. They were expected to have knowledge of table arrangements and bodily comportment as they interacted with the objects at Kingscote.[100] Sonic effects, including polite conversation or raising glasses at the mahogany table, referenced a particular conduct and interaction with objects in the room. Sounds emanated from objects, sending cues to diners in the room.

Of all the rooms at Kingscote, the dining room stands out for its ability to unite the senses (fig. 70). Rather than an interior space heavily reliant upon the perception of sight, the Newport space plays with the interaction of sight, touch, smell, taste, and hearing to enhance and educate the senses for those dwelling in or visiting the summer cottage. Psychologist William James remarked upon the fragmentary nature of sensorial moments, and other psychologists have considered the dissonance that ensues when senses are experienced separately.[101] However, the Kingscote dining room brings together the fragmented senses in a single space in which there is a relationship among looking around the dining table, touching objects, aromatic or gustatory moments, and listening to conversation. Sight, touch, taste, smell, and hearing work together to construct the ambiance of the room, which, in turn, elevates the space and its contents by nourishing and educating the senses.

Acknowledgments

I am thankful for my time as the 2018–19 Decorative Arts Research Fellow at the Preservation Society of Newport County, which allowed me to closely study Kingscote’s interiors and decorative art. I am also grateful for the wonderful editorial team at Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide: Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, Isabel Taube, and Elizabeth Buhe (the former digital humanities editor). Additional thanks to NCAW web developer Allan McLeod for his invaluable assistance with the digital design and options to present the dining room in a legible format. The anonymous reviewers and the NCAW editors provided helpful and constructive feedback for the project, especially how best to communicate the sensorial impact of particular objects. The Museum Affairs department and staff at the Preservation Society of Newport County, including Ashley Householder, Kate McNally, Paul F. Miller, Jennifer Robinson, and Abigail Stewart provided invaluable information on the King family’s archival materials and Newport’s Gilded Age milieu. Katherine Garrett-Cox welcomed me to the Kingscote dining room and enabled my close looking. I am extremely grateful for all of their assistance. Special thanks, as well, to my University of Delaware Americanist writing group for workshopping my essay, particularly my advisor, Dr. Wendy Bellion, and Dr. Jennifer Van Horn, Megan Baker, Emelie Gevalt, Michael Hartman, Kristen Nassif, and Spencer Wigmore. I am also indebted to conversations with my colleague Joseph Daniel Litts on Aesthetic movement theories and decorative art in the dining room.

Notes

[1] Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899; repr. London: George Allen & Unwin, Ltd., 1924).

[2] Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class, 34, 129.