X

Please wait for the PDF.

The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

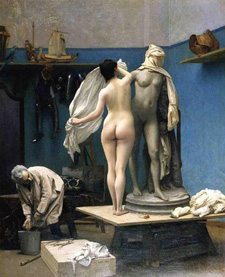

Between 1886 and 1902, at the close of his career, Jean-Léon Gérôme produced a group of painted and photographic self-portraits depicting himself at work in his sculpture studio. The author considers these works as a series through which the artist came to terms with the "anxiety of lateness" provoked both by his advancing years and the decline of the academic and official institutional structures on which he had built his career.

In their rapidly modernizing and urbanizing surroundings, the Catholic parishioners of the Rosary Church (1899–1900) in the Berlin suburb of Steglitz sought a physical connection to their medieval past via the architectural language of the neo-Romanesque. The specific variant of the neo-Romanesque style that architect Christoph Hehl envisioned for them is more than a straightforward imitation of a past style, but is instead a hybrid structure that incorporates local traditions to assert a historical Catholic presence in Protestant Prussia as well as an Italianate interior that recalls Catholicism's origins.

Before autographic color processes lent "unmediated" chromatic realism to photography in the early twentieth century, color photographs most often were sites of mixed media governed by the contrasting discourses of painterly essentialization and photo-indexical reproduction. As we investigate the relationship between these separate and often gendered aesthetics, codified in mid-nineteenth-century photographic manuals and reinforced by labor divisions and distinctions between color and form, we encounter the largely overlooked politics of applied color in early photography, and the missing history of its practitioners.

Analyses of the 1870–1871 inventory records of the London art dealing firm of Arthur Tooth reveal widespread trade collaboration that maximized the influx of new artists and optimized the opportunities for sale to the public of their works as well as other paintings by well-established artists. By functioning as both arbitrageurs and market-makers, dealers facilitated stability and growth of a now mature market in luxury goods with added speculative commodity character and thus contributed to a far greater extent to the subsequent, and still ongoing, explosion of styles than hitherto acknowledged.

In 1855, José Bernardo Couto, director of the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City, responded to a request by the president, Antonio López de Santa Anna for the creation of a gallery of national art by collecting works, which he regarded as representing the Old Mexican School of Painting. Early museum practice in Mexico, exemplified here by the public display of this formative collection, was shaped by the peculiarities of the nineteenth-century political and cultural landscape in Mexico City, which was primarily defined by the ideological tensions between Liberals and Conservatives.