The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

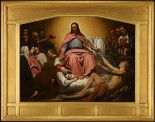

A Reduced Version of Ary Scheffer's Christ Consolator

In August 2007, Rev. Steven Olson, the pastor of Gethsemane Lutheran Church in Dassel, Minnesota, called the author of this article to ask for advice on how to authenticate a framed picture, inscribed "Ary Scheffer 1851," which had, for some time, languished in a storage closet of his church. Pastor Olson's immediate concerns were the preservation of the picture and finding a place for its display that would be accessible to the people of Minnesota. He had determined that the painting might have some aesthetic merit, that historically it was titled Christus Consolator (fig. 1), and that it had been church property since the 1930s. My immediate response to the telephone conversation with Rev. Olson was disbelief that a signature work by a renowned French academic painter had found its way to rural Minnesota and for seven decades passed completely unrecognized. Initial acquaintance with the canvas in the vault area of a Wells Fargo Bank in Dassel seemed to justify my skepticism. But careful study of the painting, which was covered with layers of discolored varnish and grime (fig. 2), revealed that this was, indeed, a well-preserved authentic signed and dated work by Ary Scheffer (1795–1858). After a year of deliberations, the church decided to donate the painting to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, thus ending its remarkable and improbable peregrinations across continents and cultures that this essay will trace.

The Dutch-born and French-trained artist, Ary Scheffer, was one of the pre-eminent Romantic painters active in Paris during the first half of the nineteenth century.[1] With his brothers Arnold and Henri he cast his fortune with the French charbonnerie, a radical republican fraternity that elected General LaFayette as its president in 1821 and Arnold Scheffer as its secretary. In 1826, Ary became drawing master to the children of Louis-Philippe, duc d'Orléans, the future king of France, for whom he would function as unofficial court painter after 1830. His earliest paintings depicted subjects from Romantic literature, topical socio-political events such as the Greek War of Independence, and sentimental genre subjects, which the critic and future prime minister Adolphe Thiers lauded in 1824 as the quintessence of his genius and of modernity itself.[2] However, after 1830 the artist became increasingly occupied with religious themes.

The initial version of Christus Consolator (measuring 6 x 8 feet) was exhibited in 1837 at the Paris Salon. Of that year's exhibition, Frédéric Mercey wrote in an article for the Revue des Deux Mondes: "Religious subjects are the mode. There is scarcely an artist this year who has not produced a painting of holiness."[3] Scheffer's principal entry garnered mixed reviews. The establishment critic, Etienne Delécluze, wrote favorably, "This slightly expansive composition, very simple, has in it a rare merit, which is that the sentiments and the visible forms of the personages are rendered with truth, delicacy, and elevation."[4] Louis Viardot, writing for Le Siècle, noted that there were two classes of religious painters in France, the traditionalists inspired by the German Nazarene artists Johann Friedrich Overbeck and Peter von Cornelius, and "innovators" like Scheffer.[5] On the other hand, the unpredictable and often irritable Gustave Planche confessed to having no idea of what Scheffer meant to portray: "The greatest fault of this composition is its obscurity."[6]

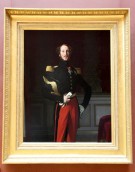

But Scheffer was a respected and much admired painter, and the Salon picture was purchased by the French monarch's eldest son, Ferdinand-Philippe, Duc d'Orléans (1810–42; fig. 3), as a present for his Lutheran fiancée, the Princess Helen Louise Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1814–58). It hung in her Lutheran Oratory until it was sold by her at forced auction in 1853.[7] The painting ultimately entered the collection of Amsterdam's Historical Museum as part of the bequest of the coal baron Carel Joseph Fodor (1801–60) in 1860. It has been on loan to the Van Gogh Museum since 1987 because of Vincent Van Gogh's great admiration for its sentiment. The artist often decorated his office or his rooms with engravings after it and its pendant ChristusRemunerator (1847; fig. 4).[8] "It can be compared to nothing else," he wrote his brother Theo.[9]

The 1851 reduced version of Christus Consolator that was donated to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in memory of the Rev. David J. Nordling, and several others of identical dimensions (26 x 36 inches) recorded in various collections (the Dordrecht and Utrecht museums, for instance), were painted by Scheffer in the early 1850s in the wake of the original painting's extraordinary popularity in Europe and America.[10] The social upheavals throughout Europe in 1848 and anti-republican political developments in France undoubtedly prompted Scheffer to revive this composition in oils. He was also profoundly distraught after the abdication and exile in 1848, and the death in 1850, of his patron, the liberal King Louis-Philippe. The American poet William Cullen Bryant, who visited Scheffer in 1849 and admired his Christus Remunerator, described Paris as an armed fortress governed by a "despotic oligarchy."[11]

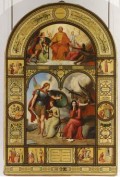

At the center of Scheffer's composition are the figures of Christ and the repentant Mary Magdalene[12] surrounded by the afflicted and oppressed. The theme of Christus Consolator, or Christ the Comforter, was inspired by Luke 4:18–19. The 1837 Salon catalogue offered the citation: "I have come to heal the brokenhearted and to preach deliverance to the captives; to liberate those who are shattered under their chains."[13] The "brokenhearted" are depicted on the left of Christ. In the foreground, a kneeling woman mourns her dead child, while in the background (from left to right) we find an exile with his walking stick, a castaway with a piece of wreckage in his hand, and a suicide with a dagger. Between these groups are Torquato Tasso—the gifted sixteenth-century poet imprisoned as a madman—crowned with laurel, and figures representing the three ages of woman. The model for the oldest woman was Scheffer's mother (fig. 6). To the right of Christ are the oppressed of both the past and present: a slave from Roman antiquity, a medieval serf, a Greek Souliot warrior, and, in front of them, a shackled African slave. The pose of the last derives ultimately from Josiah Wedgwood's 1787 design for the seal of the British Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, which was widely circulated in abolitionist tracts well into the nineteenth century.[14] With his left hand, Christ releases from his earthly shackles a dying man, the personification of Poland, with the shattered weapons of the country's failed insurrection of 1830–31 against Russia by his side, and his exposed, wounded body draped in the Polish flag.[15]

Scheffer's brilliantly balanced composition presents an encyclopedic overview of human travail that transports the viewer from modern day Poland, France, Greece, and America to both the ancient and medieval eras, and it reflects the renewed desire in France, after 1830, for a more liberal activism within the Catholic and Protestant Churches.[16] On a personal level, it also merged for the first time the artist's militant social and religious views.

Stylistically, the painting shows Scheffer's appreciation for the works of the markedly spiritual Nazarene circle in Germany. As noted by Leo Ewals, the upper half of Victor Orsel's 1832 Nazarene-inspired LeBien et le Mal (fig. 8) was probably an immediate source of inspiration for Scheffer.[17] At the same time, the picture and its reduced versions represent Scheffer's mature style of the late 1830s, a time when he competed with Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres for a place in the pantheon of French academic painters. As astutely observed by Delécluze, the 1837 version of Christus Consolator marked a bold shift in Scheffer's manner away from the manifestly dramatic compositions and the somber palette of early French Romanticism to a more profound equilibrium between measured organization, pale colors, and crisp design, which Delécluze likened to the "Roman School of Raphael," but which ultimately derived from Scheffer's cautious rapprochement, at mid-career, with Ingres's manner.[18] It was a risky conversion that troubled art critics well into the twentieth century. Planche was especially disturbed by Scheffer's "reluctance to commit to a definitive manner."[19] And in his review of the 1846 Salon, the last one at which Scheffer exhibited his work, Charles Baudelaire castigated him for his "eclecticism of style," lumping Scheffer with what he derided as the "apes of sentiment": "A simple way of knowing the import of an artist is to examine his public following. E. Delacroix has for his the painters and poets; M. Decamps, the painters; M. Horace Vernet, the garrisons, and M. Ary Scheffer, the esthetic ladies who revenge themselves on the curse of their sex [sentimentality] by indulging in religious music."[20]

The perceptive modern historian of French painting, Léon Rosenthal, would pen a similar, although slightly more analytical, assessment at the beginning of the twentieth century:

The renegade of Romanticism, Ary Scheffer, did not despise technique, but he modified it so as to efface it in favor of expression, and he made it subservient to ideas that depart from the realm of painting and belong more to the domain of literature. The Christus Consolator (1837) preaches charity, equality, and defends, not without elegance, the anti-slavery thesis…The error resides in the pursuit of an ideal that the art of painting can not attain and to which it ends up being sacrificed.[21]

Central to the theses of Baudelaire and Rosenthal was the notion that painting was vital to the degree that the artist accentuated the material process of his or her craft, while relegating narrative intentions to a subsidiary status.

Despite, or rather because of, the deployment of a painting style that promoted transparent narrative over bravura technique, Scheffer's Christus Consolator enjoyed a vast audience in Europe and America through engraved and lithographic reproductions. The crudest was an 1856 lithograph by Currier and Ives.[22] The most successful was Louis Henriquel-Dupont's polished 1842 engraving for the Parisian dealer-publisher Adolphe Goupil, who specialized in reproducing and selling Scheffer's pictures (fig. 9). The engraver exhibited an impression under his own name at the 1842 Salon,[23] and at 160 francs for an artist's proof it was one of the most expensive prints in Goupil's extensive stock. So popular was the engraving that Goupil had the worn-out plate reworked in 1860 for a reissue.[24]

In his 1864 address urging the foundation of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, William Cullen Bryant remarked:

I was once speaking to the poet [Samuel] Rogers in commendation of the painting of Ary Scheffer, entitled Christ the Consoler. "I have an engraving of it," he answered, "hanging at my bedside, where it meets my eye every morning." The aged poet, over whom already impended the shadow that shrouds the entrance to the next world, found his morning meditations guided by that work to the Founder of our religion.[25]

Bryant's valued friend, Washington Irving, who had once visited Scheffer in Paris, burst into tears before an impression of Henriquel-Dupont's engraving, which he saw in the window of a "German" dealer on Broadway (i.e., Goupil)[26] in 1848 and instantly purchased. He later noted that "there was nothing superior to it in the world of art."[27] His publisher, George Palmer Putman, was so moved by Irving's affection for this image that he purchased for him an impression of the recently engraved pendant Christus Remunerator.[28] In the southern United States, a book of common prayer was circulated by the Episcopal Church of Pennsylvania with an engraved frontispiece that eliminated the figure of the black slave.[29] This prompted a poetic diatribe on the eve of the Civil War from the American poet and fervent abolitionist, John Greenleaf Whittier.[30] Whittier had used the previously cited design by Wedgwood for the headpiece to his important abolitionist broadside "Our Countrymen in Chains" (fig. 10) which appeared in 1837. This might explain the vehemence of his attack, since it is likely Scheffer knew of that tract and copied its headpiece, in reverse, when he composed his first version of ChristusConsolator. A sonnet similar to Whittier's by Maria Weston Chapman was featured in her influential abolitionist literary annual The Liberty Bell in 1858.[31] That same year, her Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society was presented with an impression of Henriquel-Dupont's engraving on the occasion of their annual fundraising bazaar. The author of their Report of the 24th National Anti-Slavery Festival (Boston, 1858) considered the alteration of Scheffer's image "evidence of the corruption of established churches." Another instance of "defacement," this time rather benign, was the appropriation of Scheffer's figure of Christ alone for the anonymously painted altarpiece of the Episcopal Church of the Heavenly Rest in New York. That church was founded in 1865 by Union veterans of the Civil War as a memorial for their slain comrades.

During her tour of the United States between 1834 and 1836, the British author and suffragette Harriet Martineau had allied herself to Chapman and the most radical of the Boston abolitionists, including Whittier and William Lloyd Garrison, a founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society. She would later describe the significance of Scheffer's image for her, and by extension for humanity, as she recovered from a debilitating disease:

If such a picture as the Christus Consolator of Scheffer be within view of the sick-couch—(that talisman, including the consolations of eighteen centuries ! — that mysterious assemblage of the redeemed Captives and tranquilised Mourners of a whole Christendom !—that inspired epitome of suffering and solace !)—it may well be a cause of wonder, almost amounting to alarm, to those who, not having needed, have never felt its power. If there were now burnings or drownings for sorcery, that picture, and some who possess it, would soon be in the fire, or at the bottom of a pond. No mute operation of witchcraft, or its dread, could exceed the silent power of that picture over sufferers.[32]

Even the Pre-Raphaelite artist William Holman Hunt, who, like Scheffer, endeavored to create a more universal Protestant art, but who despised Scheffer's French style of painting, as a young art student in the 1840s nevertheless admired ChristusConsolator:

It was the mode in England as on the continent, to rate Ary Scheffer among the greatest of painters. He had doubtless exhibited some capable works, then in private collections. Of these we know by engravings "Mignon regrettant sa patrie" and "Christus Consolator." The first undoubtedly possessed grace, the second took the young admirer captive for a whole week like a popular air.[33]

Christus Consolator actually competed with Holman Hunt's Light of the World (1853–54) as the Protestant image most coveted throughout the Western world during the middle decades of the nineteenth century. And it is probably no coincidence that a version of Scheffer's picture, with its potent reference to African slavery, found its way to New England at the height of the Antebellum Period. In point of fact, Scheffer's pervasive celebrity in America seems, from the evidence already cited, to have rested almost entirely on the promotion of this image by the abolitionist cause.

The Dassel version of Christus Consolator was first exhibited at the Boston Atheneum in 1852, together with engravings after the composition, and again in 1856 and 1863.[34] It had been commissioned from Scheffer in December 1850 for the extraordinary sum of 9,000 francs, or the equivalent then of approximately $1,700, by the future famed Harvard art historian and social activist Charles Eliot Norton (1827–1908), as a wedding present for his sister Louisa (1823–1915) and William Story Bullard (1813–97), a principal in the Boston East India merchant firm of Bullard and Lee.[35] An anonymous reviewer of the 1856 Atheneum exhibition confirmed this provenance:

The Dante and Beatrice, by Scheffer, adds interest to the exhibition, and we see on the catalogue the title, "Christus Consolator." We hope it is the picture in the possession of W. S. Bullard, Esq, a reduced duplicate by the artist of the original picture, the latter formerly in the possession of the Duke of Orleans. This work, Christus Consolator, seems to us the noblest work of modern times in the department of Christian Art.[36]

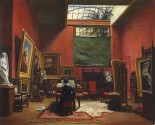

Scheffer appears to have been a darling of Boston's intellectual circles of the 1850s. Charles Callahan Perkins (1823–86), a wealthy Boston artist, historian and co-founder of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts who, in 1846, studied painting in Scheffer's Paris studio, by 1851 owned two of the artist's pictures: Macbeth and the Witches and the aforementioned Dante and Beatrice.[37] Perkins, Bullard, and Norton all traveled in Europe, albeit separately, in 1850–51. Norton arrived in late April 1850 and on May 11, with letters of introduction from Perkins, called on Scheffer's recent bride Sophie Marin, who brought him into a studio "most tastefully arranged and hung with the finest of Scheffer's paintings" (fig. 11).[38] He was then introduced to the artist in his working studio (fig. 12), where Norton's "heart beat quick at seeing the works of so great an artist and with which I had so many tender associations."[39]One of those works was a version of Christus Consolator, which he considered the finest picture he had ever seen "in point of expression," even finer than any by Titian. He would dine frequently at the Scheffers while in Paris. After commissioning the work now in Minneapolis, Norton returned to Boston just in time for the late January 1851 wedding of Bullard and his sister, who then promptly left for Europe on their honeymoon, undoubtedly returning with their finished picture eight months later.[40] In January 1852, Norton was made a trustee of the Boston Atheneum and secured the loan of the painting for their annual exhibition that year.[41] Coincidentally, in 1852 Harriet Beecher Stowe published her provocative best-seller Uncle Tom's Cabin. The following year she capitalized on her new-found celebrity by touring Europe. Her account of her visit to Scheffer's studio is of interest, in that it astutely encapsulated the conflicting public-versus-professional opinions of his stature as an artist:

During the time I was in Paris, I formed the acquaintance of Schoeffer [sic], whose Christus Consolator and Remunerator and other works, have made him known in America…Schoeffer is certainly a poet of a high order. His ideas are beautiful and religious, and his power of expression quite equal to that of many old masters, who had nothing very particular to express. I should think his chief danger lay in falling into mannerism, and too often repeating the same idea. He has a theory of coloring which is in danger of running out into coldness and poverty of effect. His idea seems to be, that in the representation of spiritual subjects the artist should avoid the sensualism of color, and give only the most chaste and severe tone…Nevertheless, in looking at the pictures of Schoeffer there is such a serene and spiritual charm spread over them, that one is little inclined to wish them other than they are. No artist that I have ever seen, not even Raphael, has more power of glorifying the human face by an exalted and unearthly expression…His best award is in the judgments of the unsophisticated heart. A painter who does not burn incense to his palette and worship his brushes, who reverences ideas above mechanism, will have all manner of evil spoken against him by artists, but the human heart will always accept him.[42]

Bullard's Scheffer was last exhibited at the Atheneum in 1863, at the height of the Civil War, in a special exhibition to aid the Boston Sanitary Fair.[43] According to a eulogy published by his partner, Bullard "gradually retired from business, devoted much time to the management of charities, where his benevolence as well as his judgment was exercised, and in his summer home sought out and 'succored, helped, and comforted all who were in danger, necessity and tribulation,' shunning as far as might be all publicity."[44] One of his sons, Francis (1862–1913), was also a patron of the arts, a director of the American Federation of Arts in New York, and a distinguished benefactor of the Boston Museum.[45]

Pastor David J. Nordling (1878–1931), the next owner of Bullard's painting, was a native of the Midwest. Born in Wahoo, Nebraska, he conducted his Lutheran ministries in Topeka and Savonburg, Kansas (1905–13), Geneva, Illinois (1915–29)[46] and Dassel, Minnesota (1929–31).[47] In 1869 the latter town was named for Bernard Dassel, the secretary of the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad, which had just completed laying its track to the site from Minneapolis. Ten years later, that nearly insolvent railway company was rescued by the renowned railroad tycoon and later co-founder of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, James J. Hill, the "Empire Builder." Consequently, Dassel would find itself advantageously perched on what was to become Hill's Great Northern Railroad, connecting Minneapolis with Seattle and providing the town with the essential links to commerce and civilization that enabled it to flourish.[48] How Scheffer's picture transferred from Boston brahmins to Minnesota parishioners is still a matter of conjecture. However, in addition to the ministries already mentioned, Nordling did serve briefly as pastor of the Salem Lutheran Church in Bridgeport, Connecticut, from 1913 to 1915. If the Bullard family disposed of their picture after William's death in 1897, or Francis's death in 1913, or most likely Louisa's death in 1915, Nordling might well have acquired it in New York, then the center of the art trade and the home of Goupil's progeny art gallery, Knoedler and Company.[49] One senior member of the Dassel congregation recalled recently that the Nordlings owned "many nice things and Mrs Nordling always came to church in fine clothes."[50]

Following pastor Nordling's death from influenza in 1931, the painting was donated by his widow to Gethsemane Lutheran. Various obituaries described Pastor Nordling as "a power in the pulpit," who "wanted to lead his people to the life in Christ. The keynote of his message was 'Repent and believe in the Lord Jesus Christ'…He willingly gave himself in bringing consolation and comfort to the aged, suffering, sorrowing, and dying."[51]

Christus Consolator graced the walls of the Dassel church on and off for seven decades, and in December 2008, one month after the election of the first African American President of the United States, an event that neither Whittier, nor Bryant, nor Martineau, nor Norton, nor Nordling would likely have believed possible, the Dassel Scheffer became the welcome consolator of the collective peoples of Minnesota.

Patrick Noon

Patrick and Aimee Butler Chair of the Paintings Department

Minneapolis Institute of Arts

I would like to thank the Rev. Steven Olson and Irene Bender for their help in researching this article. All translations from the French are the author's.

[1] On Scheffer, see Marthe Kolb, Ary Scheffer et son temps (Paris: Boivin, 1937); Leo Ewals, Ary Scheffersavie et son oeuvre (Nimègue, Privately Published, 1987); Institut Néerlandais, AryScheffer 1795 – 1858 (Paris: Institut Néerlandais, 1980); Edward Morris, "Ary Scheffer and his English Circle," Oud Holland 99 (1985): 294–323; Edward Morris, French Art in Nineteenth Century Britain (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2005), 176 ff; and Robert Verhoogt, Art in Reproduction:Nineteenth-Century Prints after Lawrence Alma Tadema, Jozef Israels, and Ary Scheffer (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007).

[2] Adolphe Thiers, "Salon de mil huit cent vingt-quatre," Le Constitutionnel, September 2, 1824, 3.

[3] Frédéric Mercey, Revue des Deux Mondes, May 1838, 389.

[4] Etienne Delécluze, Journal des Débats, March 3, 1837, cited in Kolb, Ary Scheffer, 367.

[5] Louis Viardot, Le Siècle, March 2, 1837.

[6] Gustave Planche, "Salon de 1837," in Etudes sur l'Ecole française 1831–1852 (Paris: Michel Lévy Frères, 1855), 2:66. For additional citations see Institut Néerlandais, Ary Scheffer, 21.

[7] The sale price was 52,500 francs.

[8] Letter to Theo, from England, July 8, 1876: "Many thanks; both the engravings, 'Christus Consolator' and 'Remunerator,' are hanging over the desk in my little room." Also, in a letter to Theo from Dordrecht, January 21, 1877, "I have hung in my bedroom the two engravings Christus Consolator that you have given me. I saw the pictures at the museum, as well as Scheffer's 'Christ in Gethsemane,' which is unforgettable." Institute for Dynamic Educational Advancement, "Van Gogh's Letters," WebExhibits, 2007, http://www.webexhibits.org/vangogh/letter/5/084.htm (accessed August 13, 2009). For Van Gogh's admiration for Scheffer, see Verhoogt, Art in Reproduction, 339 ff.

[9] Letter to Theo from The Hague, February 15, 1883, "That book by Thomas à Kempis is as beautiful as, for instance, Ary Scheffer's '[Christus] Consolator' – it can be compared to nothing else." Institute for Dynamic Educational Advancement, "Van Gogh's Letters," WebExhibits, 2007, http://www.webexhibits.org/vangogh/letter/12/267.htm (accessed August 13, 2009).

[10] Ewals, Ary Scheffer, 278–79. Kolb dated the Dordrecht replica to 1837 without explanation.Kolb, Ary Scheffer et son temps, 89. The Goupil et Cie stockbooks, in the Getty archives, record the sale of a reduced version on July 31, 1852 to a "V. Manke à Liège" for 4,250 francs. In the process of removing an old lining from the Dassel version, the conservators uncovered the stencil of Scheffer's color merchants, Colcomb-Bourgeois, whose shop Au Spectre Solaire,18 quai de l'Ecole, was active from 1849 to 1856 (fig. 5).

[11] Parke Goodwin, A Biography of William Cullen Bryant (New York: D. Appleton, 1883), 2:50–51.

[12] A preparatory drawing for the figures of Christ and the Magdalene is reproduced in Institut Néerlandais, Paris. 1980, no. 64.

[13] "Je suis venu pour guérir ceux qui ont le coeur brisé et pour annoncer aux captifs leur déliverance; pour mettre en liberté ceux qui sont brisés sous leurs fers." ." Salon catalogue number 1648, with the abbreviated title Le Christ.

[14] The British had abolished slavery throughout their empire in 1833, but a comparable universal abolition in French territories would not occur until 1848. Medieval-style serfdom was still an institution in Eastern Europe and Russia and would also not be abolished in the Austro-Hungarian domains until 1848. In contemporary liberal social theory, the serf also symbolized the economic bondage of the French proletariat. Souliots were Greek Albanians banished from their native region near Jannina after their defeat in 1803 by Ottoman forces. They were legendary for their fierce opposition to the Turks during the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s (fig. 7).

[15] A second, abortive rebellion of Poland against Prussia resulted in considerable carnage in 1848. In a word, the imagery of Christus Consolator remained as topical in 1851 as it had been original in 1837. Scheffer's sympathy for the suppressed Greek and Polish nationals resulted in numerous significant Salon paintings including the Femmes Souliotes and La Défense de Missolonghi, both of 1827/28. For Scheffer's involvement with exiled Poles in Paris, see L. Wellisz, Les Amis Romantiques, Ary Scheffer et ses amis polonais (Paris, Editions de Trianon, 1933). His portrait of the exiled titular head of Poland, Adam Jerzy, Prince Czartoryski (1770–1861), dates to 1850.

[16] For a thorough discussion of this phenomenon, see Michael Driskel, "Painting, Piety, and Politics in 1848: Hippolyte Flandrin's Emblem of Equality at Nîmes," Art Bulletin 66, no. 2 (June, 1984): 270–85.

[17] Institut Néerlandais, Paris. 1980, no. 22; reproduced, ibid., 281, figs. 11–12.

[18] Théophile Silvestre recognized this affinity, with some disdain, although he considered ChristusConsolator a pastiche of Overbeck; see Eugéne Delacroix: Documents nouveaux (Paris, Michel Lévy Frères, 1864), 23.

[19] Planche, "Salon de 1837," 66.

[20] Jonathan Mayne, Baudelaire: Art in Paris 1845–1862 (London: Phaidon, 1965), 99.

[21] Léon Rosenthal, Du romantisme au réalisme (Paris: Editions Macula, 1987), 195–96.

[22] Most of Scheffer's numerous English and American admirers knew the composition only through reproductions. Such was the source for George MacDonald's poetic tribute, The Consoler: On an Engraving of Scheffer's Christus Consolator, in Poems (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans and Roberts, 1857). The Nathaniel Currier lithograph is reproduced in Gail E. Husch, Something Coming: Apocalyptic Expectation and Mid-Nineteenth Century American Painting (University Press of New England, 2000), 132 fig.44.

[23] Salon catalogue number 2074, with the title Le Christ Consolateur.

[24] Verhoogt, Art in Reproduction,310ff. The price of the engraving was equivalent to three months wages for the average American worker in 1850.

[25] William Cullen Bryant, Orations and Addresses (New York: Harpers, 1873), 341.

[26] Goupil opened his New York premises in 1848 under the management of the German-born William Schaus.

[27] Pierre Monroe Irving, The Life and Letters of Washington Irving (New York, G. P. Putnam, 1883), 3:95.

[28] G. H. Putman, George Palmer Putman: A Memoir (New York, G.P. Putnam, 1912), 268.

[29] There are numerous published accounts of this perceived desecration, but see in particular, Parker Pillsbury, Acts of the Anti-Slavery Apostles (Concord, NH: Clague, Wegmen, Schlicht and Co., 1883), 437–38.

[30] John Greenleaf Whittier, "On a Prayerbook, with its Frontispiece, Ary Scheffer's 'Christus Consolator,' Americanized by the Omission of the Black Man," in Anti-Slavery Poems, Songs of Labor and Reform (Cambridge, MA: The Riverside Press, 1888), 210ff. See also, The Writings of James Russell Lowell in Prose and Poetry (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Co., 1890), 5:11ff. Lowell and Charles Eliot Norton were close collaborators as abolitionists.

[31] Maria Weston Chapman, "Sonnet: The Christus Consolator of Ary Scheffer and the Frontispiece of the American Episcopal Book of Common Prayer," The Liberty Bell (Boston: National Anti-Slavery Bazaar, 1858), 319. In the same issue was reprinted a sonnet by her sister Anne Warren Weston, which was originally published in that annual in 1844, at 174: "Sonnet: Written after seeing a picture, 'Christus Consolator." The "picture" was undoubtedly an engraving.

[32] Harriet Martineau, Life in the Sick Room by an Invalid (London, E. Moxon, 1844), 157–58.

[33] W. Holman Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (London, 1905), 1:187–88.

[34] Robert F. Perkins and William J. Gavin III, The Boston Atheneum Art Exhibition Index 1827–1874 (Boston: Boston Atheneum, 1980).

[35] James Turner, The Liberal Education of Charles Eliot Norton (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 97, and Linda Dowling, Charles Eliot Norton: The Art of Reform in Nineteenth-Century America (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2007), 58; see also Theodore Stebbins, Jr. and others, The Last Ruskinians, Charles Eliot Norton, Charles Herbert Moore, and their Circle (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 2007).

[36] "Boston Atheneum," The Crayon 3, 1856, 249.

[37] Perkins and Gavin, Boston Atheneum, 126. Perkins also owned a Scheffer drawing, titled Christ. In an obituary for Scheffer in The Crayon 5, 1858, 233, it was noted, "Five of his works have been brought to this country, namely, 'Macbeth,' 'Dante and Beatrice,' 'Christus Consolator' (a reduced copy by the artist of the original) 'Dead Christ,' and 'The Temptation of Christ.' The first three pictures belong to gentlemen of Boston; the last two are now in Europe." Perkins's Danteand Beatrice is now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

[38] See Turner, Liberal Education,88, and Sara Norton and M.A. DeWolffe Howe, The Letters of Charles Eliot Norton (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1913), 1:64.

[39] Turner, Liberal Education,88.

[40] Scheffer's record books (Dordrechts Museum) indicate that he executed two "replicas" in 1851 for a total of 11,000 francs.

[41] Norton and Howe, Letters, 1:64.

[42] Harriet Beecher Stowe, Sunny Memories of Foreign Lands (Boston: Philips, Sampson and Co., 1854), 2:351. In a letter to Theo of July 1880, Van Gogh would write: "So you would be mistaken should you continue to think that I have become less keen on, say, Rembrandt, Millet, or Delacroix…there is something of Rembrandt in Shakespeare, something of Correggio or of Sarto in Michelet and something of Delacroix in Victor Hugo, and there is also something of Rembrandt in the Gospel or, if you prefer, something of the Gospel in Rembrandt…And in Beecher Stowe there is something of Ary Scheffer." Institute for Dynamic Educational Advancement, "Van Gogh's Letters," WebExhibits, 2007, http://www.webexhibits.org/vangogh/letter/8/133.htm (accessed August 13, 2009).

[43] The Federal Sanitary Commission had been created in 1861 to promote health and sanitation in the camps of Union soldiers. Two other events of interest to this study also occurred in 1863: the placid town of Dassel, fifty miles west of Minneapolis, with a present population of 1300, received its first settlers, while in Paris, Ernest Renan published his immensely popular and controversial "biography," The Life of Jesus, which endeavored to humanize Christ, while challenging the notion of his divinity. Renan had married, in 1856, Scheffer's niece and was intimately familiar with her uncle's various characterizations of Christ, something which perhaps did not escape Marcel Proust, who admired The Life of Jesus but nevertheless was compelled to opine that "Renan felt bound to invest all his best passages with a pomp very much Ary Scheffer." Preface to Paul Morand, Tendres Stocks (Paris, Editions de la Nouvelle Revue Française, 1921), 6.

[44] John T. Morse, ed., Memoir of Colonel Henry Lee with Selections from His Writings and Speeches (Boston, Little, Brown, and Company, 1905), 408.

[45] Leila Mechlin, ed., Art and Progress, a Publication of the American Federation of Arts 4, no. 8 (June 1913): 1005.

[46] Geneva, near Chicago, is in Kane County, one of the most active centers for the Underground Railroad during the 1840s.

[47] Archives SW, Augsburg College, Minneapolis.

[48] Warren Upham, Minnesota Geographic Names, Their Origin and Historic Significance (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1920), 17:339.

[49] Goupil and the successor firm of Boussod, Valadon et Cie continued to buy and sell Scheffer oils into the 20th century.

[50] Oral communication from Irene Bender, May 2009.

[51] Rev. Prof. S. J. Sebelius, ed. My Church, an Illustrated Lutheran Manual (Rock Island, IL: Augustana Book Concern, 1929–31), 18:176–80.