The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

|

S. Bing and L.C. Tiffany: Entrepreneurs of Style |

||||||||||

|

The figures of Siegfried Bing and Louis C. Tiffany loom large in the history of decorative arts at the turn of the century.1 Men of great taste, they used their wealth and status to further their very particular conceptions of artistic beauty. Acting as impresarios to promote their artistic visions through commercial empires, they dealt in that precious and most fickle of commodities: objets d'art. | ||||||||||

| The importance of their alliance has long been recognized, but it has been considered in only the broadest of terms. Although there is no trace of their letters or other communications, and there are no pertinent business records from either firm, still, their relationship can be charted more closely than has been realized. As will be seen, they entered into an agreement well before Bing officially opened his L'Art Nouveau gallery, and that during a period of approximately six years, Bing was extremely effective in promoting Tiffany's favrile glass and lamps throughout Europe, more so than Tiffany was able to do at home. Bing's subsequent shift of focus in the operation of his gallery brought this working relationship to an end by 1900, earlier than has previously been realized. An equally important aspect of this interchange is the effect that Bing had on Tiffany, subtly influencing the course of Tiffany's glassmaking and entry into ceramics. In short, a closer study of their collaboration reveals a great deal about both men's fascinating careers. | |||||||||||

| Essentially of the same generation, Bing was the older, having been born in 1838 while Tiffany was born ten years later. Although from very different cities, Hamburg and New York, both were the sons of prosperous merchants dealing in the decorative arts. Bing's family had imported glass and ceramics as well as Japanese wares, and then began manufacturing porcelain in France. Similarly, the Tiffany family's haberdashery business shifted to jewelry, silver, and imported European luxury porcelains and glass.2 Whereas the young Bing directly entered his family's business and took control by the mid-1860s, the young Tiffany tried to become a painter and not until the late 1870s did he set up in business as an interior decorator. | |||||||||||

| Their mutual admiration of Japanese art probably brought them into contact by the 1880s. Tiffany undoubtedly frequented Bing's Paris store. Moreover, Bing had a convenient branch office in New York City, and ran several auctions of Japanese art in that city. Edward C. Moore, head of Tiffany & Company's silver department and a client of Bing's, probably provided an important link between the two men.3 Also, the maecenas Henry O. Havemeyer was a client of both, furthering the probability that Bing and Tiffany were in contact, if not already colleagues and friends, by the early 1890s. | |||||||||||

| Bing's and Tiffany's relations strengthened in 1894. Bing arrived in New York in February of that year, partially for business reasons but also because he was charged with surveying American art for a publication commissioned by Henri Roujon, director of the Beaux-Arts Administration. Bing visited Tiffany and, probably together with the artist and the patron, saw the extravagant interior of the Havemeyer house which Tiffany had just completed. Bing described the mansion in rapturous terms.4 This opulent commission marked the apex of Tiffany's career as an interior designer, never to be repeated; at that moment, though, it must have seemed as if Tiffany and the New World held the key to the future. | |||||||||||

|

Bing also was one of the first to set eyes on Tiffany's entirely new favrile glass, which had not yet been shown to the American public (fig. 1).5 He wrote glowingly:

Bing's text correctly perceived all that was new and wonderful in Tiffany's glass, and expressed it in clearer terms than Tiffany's own publicity did. |

|||||||||||

| The meeting between Bing and Tiffany in 1894 was fortuitous because it came at a critical time in their careers, as both men were reformulating their business goals. Bing was considering shifting from the trade in Oriental art to the sponsorship of modern painting and decorative arts, just as Tiffany had begun to enlarge the scope of his operations with a new emphasis on the production of blown glass vases, lighting fixtures, and other objets d'art.7 Bing's admiration of Tiffany's endeavors was overflowing. He described Tiffany's operation as "a vast central establishment grouping together under one roof an army of craftsmen in all media: glass makers, jewel setters, embroiderers and weavers, casemakers and carvers, gilders, jewelers, cabinet makers–all working to give form to the carefully considered concepts of a group of directing artists, they themselves united by a common current of ideas."8 Bing soon announced a similar program, as he sought artists whose works "manifested a personal conception in accord with the modern spirit."9 Tiffany fit this bill to a tee. The reorientation and reorganization of their respective companies should have led to lively discussions and the realization that their new goals could be mutually beneficial.10 | |||||||||||

| Bing may well have sensed that Tiffany's works had a commercial future in Europe. In doing so, he followed the lead of André Bouilhet, son of the famous silversmith, who had greatly admired Tiffany's work at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893 and had actually met with the artist in New York.11 Bouilhet's glowing report of Tiffany's "very new and personal American feeling for art" was published that year, and in January 1894 the Musée des Arts Décoratifs bought (but did not receive as a donation from Tiffany, as had been promised) fifty examples of the American's window glass.12 Similarly, Julius Lessing, the perspicacious director of the Kunstgewerbe Museum of Berlin, visited New York and Chicago in 1893 and reported that the Tiffany Glass & Decorating Co. was "one of the most inventive art industries of the world."13 He purchased a few examples of the new favrile vases as well as five lighting fixtures.14 All this transpired before Bing had left France, and thus he may well have felt encouraged in thinking that he could purvey Tiffany's work in Europe. | |||||||||||

| Bing and Tiffany established a contractual agreement probably in the opening months of 1894, stipulating that Bing was to serve as the American's sole representative in Europe.15 A group of Tiffany glass vessels and at least one window were sent to the Spring 1894 Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, an organization that Tiffany had just joined as an associate member. Bing's hand in bringing this about was mentioned by his close associate, Julius Meier-Graefe.16 | |||||||||||

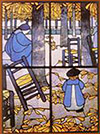

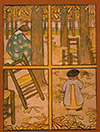

| Louis de Fourcaud, writing in the influential Revue des arts décoratifs, reported that critical opinion was divided on Tiffany's exhibit. He was forthright in his hostility, terming the vases simplistic rather than simple: "I do not like the often haphazard forms or the sharp and raw colors."17 Fourcaud was no kinder toward the window on exhibit (described as showing a lantern), which he dismissed as a "curiosity, nothing more."18 Nonetheless, Bing was successful in selling Tiffany glass to museums in the French capital. On 2 June 1894, he sold a vase to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, and a small window with a repetitive pattern of flowering mustard plants—a quite unusual format for Tiffany (figs. 2,3).19 With mounting success, Bing also sold two flowerform vases to the Musée du Luxembourg.20 | |||||||||||

| It may not have been until the fall of 1894 that Bing had the chance to proclaim himself Tiffany's sole European representative.21 In an advertisement with fairly uninteresting typography (fig. 4), he proclaimed his store the "Sole Agent for the Marvelous Designs from the House of Tiffany of New York (Tiffany Glass)." It should be remembered that at this time Bing was still selling Asian art, and his new gallery was not scheduled to open for another year. | |||||||||||

| Another project that Bing began in the spring of 1894 with his new store in mind, was the commissioning of designs from various French artists to be executed as leaded windows by Tiffany's workmen in New York. This project satisfied two goals: it realized Bing's vision of uniting the fine and decorative arts, and it was a wonderful opportunity to introduce Tiffany's glass to the European market. Turning to the Nabis, whose avant-garde ideas on the union of painting and decoration coincided with his,22 Bing discussed the project first with Henri Ibels in May 1894. Ibels then alerted Edouard Vuillard who, in turn, wrote to Maurice Denis. They, perhaps with still others, met with Bing in early June, saw samples of Tiffany glass that Bing had in his possession, and agreed to the project.23 Most of the remaining Nabis joined the project: Paul Sérusier, Pierre Bonnard, Paul Ranson, Ker-Xavier Roussel, and Félix Vallotton. In addition, Bing obtained designs from Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, the decorative painters Albert Besnard and P.A. Isaac, and the famed designer Eugène Grasset. | |||||||||||

| Surprisingly little was done to make the windows conform as a series, suggesting that the terms of Bing's commission were not exacting. The cartoons (and thus the windows, since they were made directly to the scale of the cartoons) differed considerably in size and format.24 Some were tall and thin, others small and essentially square. Roussel and Ibels' designs are divided by heavy crossbars into four equal segments, suggesting that they planned theirs in tandem. One of Ranson's windows features a patterned border on all sides following the format he used for embroidered wall hangings. Sérusier's eight very small windows were at complete variance with the series. Although we lack images of the windows by Grasset, Besnard, and Isaac, it seems likely that their designs were equally disparate.25 | |||||||||||

| At the end of October 1894, Bing was ready to send most of the cartoons to New York,26 and by the following April most of the completed windows had arrived back in Paris in time to be included in the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts.27 In general, Tiffany and his workers remained quite faithful to the French designs.28 The cartoons had been painted as fairly flat planes of color, although with rather loose brush work, and this was admirably translated into glass by Tiffany's so-called selectors who chose glass to match the cartoons. Many of the French artists, despite the two-dimensional nature of their art, could not resist some indications of drapery folds, even if in the broadest of terms, and these were cleverly duplicated by Tiffany's shop through the use of his much vaunted drapery glass. Some minor deviations were made by Tiffany's workers because the French artists had not considered the medium of leaded glass carefully enough. For example, Roussel did not take into account how the pattern of fallen chestnut leaves on the ground in his cartoon could be converted into leaded glass, but Tiffany did it by extending the leading lines (figs. 5, 6). Roussel planned a woman's robe with a pattern of large dots, but Tiffany substituted glass with a random mottling. Likewise, Bonnard's indications of a plaid pattern for the mother's dress were disregarded. To his credit, Tiffany followed the avant-garde, two-dimensional principles of the designs, although his own art tended to be much more academic. One wonders if he had a memorandum from Bing with specific instructions. | |||||||||||

| The critical reaction to the windows was varied. Tiffany tried to secure a positive reaction by distributing copies of his essay "American Art Supreme in Colored Glass," but this did not win all critics over.29 Meier-Graefe was extremely positive but, as will be seen, the Germans were generally much more enthusiastic about Tiffany's work than were the French.30 Roger Marx stood out among the French for his positive response, by praising the jewel-like quality of the glass and the pairing of these artists with such a project, and extolling the windows' "absolute beauty."31 Typical of the opposition, René de Cuers was cautiously judicious: "Whilst they are not beautiful in the absolute meaning of the word, they are certainly interesting on several grounds." De Cuers pronounced the design of Roussel's Le jardin to be "very primitive but the artlessness of the impression felt makes one smile and forgive." On the other hand, he considered the designs by Ibels and Lautrec to be "fantastical to a degree, and only of very relative interest."32 More openly negative, Louis de Fourcaud rejected Tiffany's essay as "a bizarre manifesto," questioned the appropriateness of the subjects as well as the simplicity of the designs, and criticized aspects of the glass and the way it was used.33 In short, he concluded, these windows had only a secondary significance. | |||||||||||

|

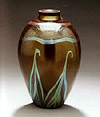

Tiffany's glass was, of course, included in the opening of Bing's shop on 26 December 1895. Vases and bowls filled a vitrine on the ground floor, just before the staircase leading to the upper levels.34 Despite the prominence of this position, we should remember that Tiffany was not the sole glass artist whom Bing represented; Emile Gallé and Karl Köpping were also featured. As the technique of Tiffany's glass evolved, shipments of the latest work were dispatched from New York. As Bing wrote in 1897, "the artist sends me examples once in a while."35 Tiffany's new work was submitted to each year's Salon, where the artist's name was always coupled with Bing's address.36 Whereas the first vessels tended to have opaque, mat surfaces, the glass made after 1895 possessed richer blues and golds, more intricate patterns, and greater iridescence (fig. 7). While Meier-Graefe waxed enthusiastically over the magical effects of the favrile glass, most French critics were not as easily won over.37 | ||||||||||

| Bing remained singularly successful, however, in selling examples of Tiffany's glass to Parisian museums. In addition to placing several more examples in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Bing sold favrile glass to the Musée Galliera, the Musée des Arts et Métiers, and the national museums at Sèvres and Limoges. Although Bing was unable to market Tiffany's glass to French provincial museums, his achievement is nonetheless amazing, especially as almost no museums in the United States were yet interested in owning examples. | |||||||||||

|

Also, Tiffany began sending examples of his fuel and electric lamps to Paris. One of these lamps was exhibited in Bing's second L'Art Nouveau exhibition in February 1896, well before they were being shown to the American public.38 A special exhibition of the lamps was staged in Bing's gallery in the summer of 1897.39 They were extravagant creations, some a meter high, such as the one photographed in Bing's studio (fig. 8). Critics noted their faintly Byzantine or Moorish quality. The jeweler Henri Nocq described one of the lamps as "Byzantinish-Japanesish-eccentric" and, although he thought the glass was beautiful, he did not like the lamp.40 Indeed, many critics, not unjustly, questioned their proportions. Also to be mentioned are the lamps with enameled copper bases where Tiffany skillfully balanced and harmonized the colors, textures, and iridescence.41 Tiffany then introduced electric lamps, thinner and taller than the squat forms required by the fuel containers. Although little is known about Tiffany's earliest electric lamps, one of the first recorded examples is the one shown in the 1898 Salon. Here again, not only would Bing have been involved in this exhibition but also he had examples of these new models for sale at his gallery.42 | ||||||||||

|

Whereas Bing's dealings with museums are well documented, his day-to-day transactions within the gallery are obscure because of the lack of extant business records. One insight into the sale of vases to private clients is afforded by the recent appearance of one of Bing's presentation boxes holding its original Tiffany vase (fig. 9). Covered on the exterior with a European Art Nouveau textile, and lined with white satin bearing the store's name stamped in gilt letters, the box is intended to stand upright, with the wings opened. The vase is thus enshrined like a holy relic and presented as an object of great value, which is appropriate since so many European critics were shocked by the high price level of Tiffany's glass.43 | ||||||||||

| Bing's vigorous efforts on behalf of Tiffany extended across Europe. Belgium was a natural place to turn since that country was open to modern developments in the decorative arts and Bing had good contacts there through his sponsorship of Henry van de Velde and Georges Lemmen. Tiffany glass was successfully exhibited at La Libre Esthétique in Brussels in 1896 and again in 1898.44 Bing even sold several vases to the Brussels Musée des Beaux-Arts. The contrast between the enthusiastic response to Tiffany's work from Belgian commentators and the frequently negative criticisms of the French is indicative of the problems that Bing faced at home. Bing apparently brought Tiffany's glass to the Dutch public as well, consigning vases to the Arts and Crafts Gallery in The Hague.45 | |||||||||||

|

A still more important terrain for Bing's campaign was Germany.46 He not only had many contacts there, as well as facility with the language (although his correspondence remained in French), but the Germans were exceptionally open to the avant-garde design of foreigners. Bing's advertisements in German magazines prominently listed his monopoly on Tiffany glass (fig. 10), something not yet in evidence in his advertisements in French magazines. His first major effort in Germany was at the Internationale Kunst-Ausstellung in Dresden in May 1897.47 His participation included an installation of five rooms, primarily those from the inaugural 1895 Paris exhibition with the addition of a large smoking room, a salon de repos, by Van de Velde. On display were paintings from some of the artists Bing sponsored, ceramics by Alexandre Bigot and Adrien Dalpayrat, glass by Emile Gallé and Tiffany, one of the Tiffany windows after Ranson and, as well, lamps and other bronze objects by Tiffany. The Ranson window and perhaps even some of the glass was left from the 1895 opening exhibition, but the lamps and the metalwares were of recent vintage.48 While we might be tempted to emphasize Tiffany's importance at Dresden, he was but one of the many artists whom Bing showed there.49 In fact, although Bing sold some Tiffany vases,50 few reviews even mentioned the New Yorker's work. Nonetheless, the exhibition proved to be a crucial turning point, and Bing soon was circulating exhibitions of Tiffany glass throughout the German-speaking world. | ||||||||||

| In the summer of that same year, Bing staged an exhibition of Tiffany glass in the Nordböhmischen Gewerbemuseum in Reichenberg with the help of its director, Gustav Pazaurek.51 In August, Bing also contacted Artur Ritter von Scala, director of the Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst in Vienna, with the hope of traveling the Reichenberg show further to Vienna and Berlin, and was successful in regard to Vienna.52 For that venue Bing prepared a substantial and insightful essay on Tiffany's glass which appeared anonymously in Kunst und Kunsthandwerk.53 When Tiffany's vases were exhibited in Vienna, the price tags were left on, according to one observer, so that viewers would recognize their value.54 Not only did the museums in these cities buy examples of favrile glass (Reichenberg bought three, Vienna bought six), but also the Bohemian glass industry took notice of Tiffany's work. Within a short time various factories, such as those of Graf Harrach and Loetz Witwe, were producing imitations of his forms and iridescent surfaces. Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, but such emulation encroached upon Tiffany's business since these Bohemian firms, especially Loetz Witwe, were able to produce glassware with similar effects at far less cost. It is all the more surprising, then, that Bing apparently represented Loetz for at least a short while.55 | |||||||||||

| Through Bing's efforts, Tiffany exhibited in Munich in 1897 at the VII International Kunst Ausstellung, showing vases, windows, and lamps.56 Six of his vases were bought for that city's museum.57 Ever active, in the autumn of that year Bing began negotiations with Jenö Radisics de Kutas of the Iparmüvészeti Múzeum in Budapest.58 Bing proposed sending his Tiffany exhibition on from Vienna, but Kutas preferred a larger show, and so Bing prepared one that included not only fifty examples of Tiffany glass, but also pottery by Bigot, porcelains from the Rörstrand and Royal Copenhagen Porcelain factories, Walter Crane wallpapers, and posters by Mucha and Toulouse Lautrec—all of which appeared in an exhibition entitled "Modern Art" that opened in the spring of 1898. The museum acquired ten examples of Tiffany glass, another instance of Bing's excellent salesmanship. | |||||||||||

| Not only was Bing successful in showing Tiffany's work in a surprisingly large number of museums within the German-speaking world (something he never achieved in France), but he also distributed Tiffany glass and other objects to commercial art galleries there. An 1897 exhibition at Littauer's Kunstsalon in Munich paired Tiffany's glass with works by Emile Gallé and the lustered pottery of the von Heider family, artists whom Bing showed in Paris.59 The following year, there were exhibitions of Tiffany glass at Gurlitt in Berlin and at Ernst Arnold in Dresden (the latter with approximately one hundred examples).60 All of these gallery venues were the unannounced results of Bing's campaigning. The Hohenzollern-Kunstgewerbehaus Hermann Hirschwald in Berlin, Kunstgewerbe-Magazin Georg Leykauf in Nürnberg, and Firma Meyer of Karlsruhe were other firms through whom Bing distributed Tiffany's glass, not only to the German public but also to museums.61 In modern terms, Bing acted as the European distributor of Tiffany's work and these were retail outlets. | |||||||||||

| Bing may have also been instrumental in the inclusion of Tiffany's work in the 1897 exhibition of decorative art in Stockholm.62 Twenty-four examples of favrile glass and two windows were included there under Tiffany's name and with his New York address, but it seems unlikely that he would have undertaken this enterprise himself, whereas such action would be in line with Bing's modus operandi. Here again, the museums in Stockholm and Trondheim were persuaded to buy seven and one examples, respectively.63 | |||||||||||

| Aware of the strongly negative reaction from the French buying public and from many critics, Bing began to change the nature of his business about 1897-98.64 Rather than merely representing the works of diverse craftsmen, each with a particular style of his own, he determined to present a unified look by creating a house style, one which would be more acceptable to the French. This entailed hiring his own staff of designers—principally Edward Colonna, Georges de Feure, and Eugène Gaillard—and controlling the manufacture of the objects. Bing thus assumed the roles of director, producer, and general entrepreneur. He saw to it that the choice of materials and the forms of the objects veered to a French, more elegant mode. Although the Belgian whiplash line of Van de Velde and Lemmen was retained, Bing's designers refined it. Writers at the time frequently noted Bing's new direction, but neither they nor modern historians recognized the negative consequences that this move would have for the relationship between Bing and Tiffany. | |||||||||||

| One of Bing's first projects was commissioning Colonna to design beautiful enameled and jewel-studded mountings to adorn Chinese snuff bottles, Bigot ceramics and, not least of all, Tiffany favrile vases that he had in stock, thereby transforming these diverse objects into ones with a common, modern style (fig. 11). Indeed, when exhibited, these new works were acclaimed for their suave elegance and this, after all, was exactly Bing's intention. Apropos of this project, modern historians have often written of it as a collaboration but, in all probability, Tiffany was a passive participant. One wonders if he even knew of it until after it was accomplished.65 | |||||||||||

| The last exhibition that significantly involved Tiffany was the one Bing staged in May 1899 at the Grafton Galleries in London. There were three major components: a selection of French paintings, sculpture by Constantin Meunier and, finally, a major display of works by Tiffany.66 The elaborate catalogue included an English translation of the Bing essay that had first appeared anonymously in Kunst und Kunsthandwerk apropos of the Tiffany exhibition in Vienna. Frank Brangwyn's poster for the exhibition gave Tiffany's glass its due prominence (fig. 12). In addition to the many favrile glass vases, there were examples of Tiffany's most recent work in bronze, including chandeliers and electric lamps, some with leaded shades.67 Also on exhibit were tabletop items in bronze and glass such as inkwells, paperweights, powder boxes, and tea screens. In short, this selection of Tiffany's work was extremely comprehensive and up-to-date, more so than any showing of Tiffany's work in the United States.68 | |||||||||||

| As well, many of Tiffany's windows, mosaics, and cartoons were on display at the Grafton Galleries. Tiffany's 1895 window after Ranson, La Moisson fleurie, was illustrated in the catalogue, but none of the Nabi windows were formally listed. On the other hand, Bing commissioned special new window designs from Frank Brangwyn, continuing the tradition he had begun for the 1895 Paris opening.69 His choice of the English artist was undoubtedly to attract a favorable response from English critics and purchasers, but it should be remembered that Brangwyn had been associated with Bing from the start of the L'Art Nouveau venture.70 Two of Brangwyn windows were listed in the Grafton Galleries catalogue: Music and The Baptism of Christ (fig. 13);71 a third window after Brangwyn, Youth Picking Eggplants, was undoubtedly commissioned at the same time, and additional cartoons for windows suggest that the project was remarkably large in scale, much more so than has been previously noted.72 | |||||||||||

| Tiffany's featured role at the Grafton Galleries exhibition and the generally favorable press accorded his work mark a high point in his business association with Bing. Brangwyn's poster design was even reused for general advertising of Bing's gallery in France and Tiffany's name was again given prominence, but this was a momentary height.73 In fact, the Grafton Galleries exhibition proved to be both the culmination and the conclusion of the close bond between Bing and Tiffany. This ending, unnoticed in the literature, was predictable since Bing's new role as a producer of his gallery's own designs left little place for Tiffany's or any other outsider's work. Bing's pavilion at the Paris World's Fair of 1900 and its magnificent display of rooms by Colonna, De Feure, and Gaillard marks the triumph of Bing's French art nouveau style and the new orientation of his business. Although Bing continued to represent Tiffany and showed examples of his glassware and lamps in most of these rooms, they were merely accessories to set off the furniture of his new trio of designers. To be sure, Tiffany glass is visible in the vitrines in Colonna's and de Feure's salons at the 1900 World's Fair (fig. 14), and on the toilette table in de Feure's dressing room. As well, Tiffany fuel lamps were placed on tables in Colonna's salon and Gaillard's dining room. These elements, however, represented a residue from the past. By contrast, Tiffany's own display at the 1900 Paris Fair, although constrained in a relatively small booth, showed many of his newest innovations. The impressive bronze and glass torchères at the front of the stand, as well as smaller lamps and the Havemeyer punch bowl in his vitrines, testify to aspects of his oeuvre that were markedly absent from Bing's pavilion. Equally significant, Tiffany was evidently selling his work directly to private clients at the fair and even to European museums, such as the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg.74 Although Tiffany may have stopped sending Bing shipments of new wares, at the end of the fair, he evidently left some of his unsold objects behind with Bing.75 | |||||||||||

| Bing still continued to sell Tiffany's works to European museums in 1900 and 1901, especially in the wake of the excitement of the Paris World's Fair. Two vases went to the Musée du Luxembourg but, expectably, non-French museums were more receptive. Among the purchasers were the museums in Berlin, Hamburg, Darmstadt, Leipzig, Brno, Zurich, Copenhagen, and Trondheim.76 However, many of the objects were executed and received by Bing prior to 1900, and did not represent Tiffany's latest work. A few favrile vases, such as one in paperweight technique bought by the Musée du Luxembourg, were of recent manufacture, but a good number were from older stock.77 Likewise, the enamels sold to Berlin and Leipzig and the lamp with an enameled base sold to Copenhagen were of fairly recent origin, but the lamp bought by Trondheim has an opticut shade which is a type of shade that was briefly in production a few years earlier.78 | |||||||||||

| It was a sign of the changing times that Bing divested himself of some of his Tiffany stock. Some favrile glass was sold to his colleague Julius Meier-Graefe, whose newly-established gallery in Paris, La Maison Moderne, took over aspects of Bing's original operations. In 1900, Meier-Graefe sold the Copenhagen museum a very early Tiffany favrile vase which must have been part of the original 1894 shipment to Bing.79 An undated price list from La Maison Moderne lists additional Tiffany glass objects, suggesting that Bing had sold or transferred much of his unsold stock to Meier-Graefe.80 | |||||||||||

|

The decline of Bing's interest in promoting Tiffany was gradual, without any specific rupture. In fact, in the spring of 1900 Bing's advertisements in Art et décoration mentioned Tiffany glass, perhaps only for the third time in any of his French publicity campaigns (fig. 15).81 But then, just a few months later, still newer advertisements no longer referred to the American glass.82 Bing occasionally employed some of his Tiffany glass for his store's new products. For example, de Feure designed a three-armed candelabra that used small Tiffany glass globes, and he added mountings to favrile glass, creating lamps and objets d'art.83 Even more interesting, a small Tiffany window with iris and ducks that had been brought to the Paris World's Fair was changed by one of Bing's other designers, Adrien Delovincourt, into a fire screen with a wonderful Art Nouveau wooden frame (fig. 16).84 Significantly, Tiffany did not collaborate on most of Bing's new projects. It is striking, for example, that he did not execute the series of four windows representing the Seasons designed by de Feure and shown in Bing's pavilion,85 nor was favrile sheet glass used in Colonna's Victor Hugo bookcase and other furniture that required ornamental glass.86 | ||||||||||

| Both Bing and Tiffany exhibited at the great International Exposition of Decorative Art in Turin in 1902 but, as might be expected, they showed separately. Bing emphasized the new side of his business by showing just the furniture and accessories designed by his staff. His hanging some of the 1895 Nabi windows executed by Tiffany, including Vallotton's Les Parisiennes, was an exception. One writer explained this as stemming from "his old friendship" with Tiffany, but it was also an expedient way of trying to sell old stock and at the same time decorating the walls.87 On the other hand, in his own exhibit, Tiffany emphasized the new aspects of his work, including glass vases in paperweight technique, new enamels, bronze and glass candlesticks, and electric lamps–including the now-celebrated Pond Lily and Wisteria models.88 | |||||||||||

| Despite the gradual termination of their business relationship, Bing and Tiffany must have remained on friendly terms. However, with each passing day, the end of their joint venture approached, especially as Bing's own business wound down. At the end of 1903 or the early part of 1904, Bing returned his unsold stock of Tiffany glass to New York.89 In lieu of Bing's gallery, Tiffany Studios lamps and perhaps other objects were displayed at the Paris branch of Tiffany and Company on the avenue de l'Opéra.90 Tiffany stopped exhibiting at the annual Salons after 1901, a good measure of the changed climate, but still he used Bing's address in the next years' catalogues, due perhaps to nothing more than convenience.91 Yet in 1905 even this came to an end. By then the principal contents of 22 rue de Provence had been auctioned off and Bing had retired to Vaucresson.92 Consequently, for the first time, the 1905 Salon catalogue listed Tiffany's address at the Tiffany & Company store on the avenue de l'Opéra.93 | |||||||||||

| Tiffany never regained the same intense level of interest in Europe that Bing had won for him. After a brief respite, Tiffany exhibited again at the Paris Salon in 1906, won prizes there, and donated several splendid examples of his favrile glass to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. Encouraged, he showed at subsequent Paris Salons and was awarded significant prizes. Around 1913, Tiffany tried returning to the German market, granting a monopoly to Georg Leykauf of Berlin, the same organization that Bing had sold to before 1900.94 But whereas Tiffany had given Bing some of his most novel and expensive glass, he sent Leykauf small, low-priced items of only commercial interest. Without Bing's support, there was no longer any substantial publicity about him in the European press, nor was he included in museum exhibitions there. The magic that Bing had created remained but a memory. | |||||||||||

| This account need not end on a sad terminal note, as though this were a twilight of the gods. Like all good artists, Tiffany was inspired by the ideas of his colleagues. As Leslie Nash reported, "Mr. Tiffany would return from Europe filled with ideas."95 We therefore should consider the positive effect that Bing had on Tiffany's work, especially since his designs from the late 1890s onward reveal new developments that appear to be the result of his contact with Bing. | |||||||||||

|

Although Tiffany never became an Art Nouveau designer in the same sense that van de Velde and Gaillard were, nonetheless, through his association with Bing, he became sensitive to the dynamics of the new style. A new sense of linear, rhythmically structured pattern emerged in Tiffany's work in the second half of the 1890s and this, I believe, is attributable to his awareness of the style that Bing was so actively promulgating. It is significant that around 1897 the surface decoration on Tiffany's glass vessels became organized into clearly conceived bands with rippling stripes and an abundance of emphatic curlicues of a distinct aspect (fig. 7). Unlike the random, accidental configurations on the early favrile glass, these vessels have insistent design elements that parallel the emerging Art Nouveau style in Europe. Similarly, Swirl, one of Tiffany's first sets of desk accessories, introduced before 1900, has a rippling, linear pattern (fig. 17). The rhythmic lines frequently reverse direction, and while not as bold or dynamic as the graphic elements in Lemmen's advertisements for Bing (figs. 10, 15), still, the underlying principle is similar. Likewise, the dynamic structure and decoration of the fabulous Havemeyer punch bowl shown at Paris in 1900 (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA), should be seen in this context. One could, of course, claim that this influence came from a general awareness of the European Art Nouveau movement, but given Tiffany's close relationship with Bing, it seems reasonable to explain the source of his development in that context. | ||||||||||

| Similarly, the lettering which Tiffany's firm introduced just before 1900 shows a distinct departure from what he had been doing earlier. Throughout the 1890s, textual passages on the company's windows were written in either proper Latin or Old English letters. Then, before 1900, as seen in the Four Seasons window (fig. 18), Tiffany Studios employed an alphabet composed of rhythmic strokes. While perhaps not as characterful as the wholly Art Nouveau letters seen in Bing's advertisements, still, they are of a distinctly modern style. This new alphabet can be seen in many other Tiffany windows after 1900 as well.96 Even the monogram of Tiffany's firm changed to a more fluent design. Here again, I believe that it was contact with Bing that caused this innovation. | |||||||||||

| Bing's influence is especially manifest in the establishment of a pottery department at Tiffany Studios. In 1900, after Tiffany returned from the Paris World's Fair, he reported that he had been impressed by the European ceramics he had seen there and that he would try his hand at this medium.97 By the end of the year, experiments had begun. Bing's role in this development was not made evident until the middle of 1901 when, by prior arrangement, a representative group of French ceramics from Bing's gallery was put on display in the Tiffany Studios showroom in Manhattan (fig. 19).98 It was a varied assortment, representing the fairly catholic taste that Bing had: the sang-de-boeuf glazes of Dalpayrat and Ernst Chaplet; the mat-glazed stoneware of Bigot, Auguste Delaherche, Jean Carriès, Paul Jeanneney, and Georges Hoentschel; and the pâte-sur-pâte porcelains of Taxile Doat. These works, championed by Bing prior to 1900, were essentially old stock of the type that Bing was trying to disperse.99 | |||||||||||

| A fascinating memento of this venture is a vase that apparently went unsold and which Tiffany Studios then turned into a lamp.100 A squat, brilliantly colored vase by Dalpayrat was fitted with a heavy shade of turtleback tiles (fig. 20).101 Whereas Bing had previously converted some of the Tiffany favrile vases into lamps, here Tiffany reversed the role. | |||||||||||

| Meanwhile, Tiffany's craftsmen were experimenting to create a line of artistic pottery of their own, though they worked in deepest secret.102 It evolved slowly, with the first examples not shown until early 1904 at the St. Louis World's Fair and the following spring in New York.103 Finally, in late 1905 (well after Bing had closed his gallery and retired), a full range of Tiffany Studios' pottery was released to the public in conjunction with an exhibition celebrating the opening of the new store of Tiffany & Company.104 Would anyone have been able to discern Bing's role in this development? I think not. The floral forms and the distinctive ivory and mossy green glazes (fig. 21) are totally in accord with Tiffany's aesthetic and have little in common with the French pottery that he took from Bing. 0ne can recognize how the French conception of matt and bleeding glazes inspired the American work, and also some of Doat's gourd forms and Hoentschel's sculpted floral decoration inspired Tiffany's vegetal shapes, but Tiffany's pottery totally transformed the French models. | |||||||||||

| One could wish that Bing had exerted greater influence on Tiffany, especially when it came to an appreciation of modern art. Despite the fact that Tiffany so successfully translated the Nabi cartoons into stunning glass windows, he remained essentially immune to such daring design, even though it suited his medium of colored glass. Tiffany never commissioned avant-garde artists, not even American ones, to design for him. This conservative approach is especially evident in his figurative windows, whether religious or domestic, largely because he relied on uninspired academic artists like Frederick Wilson. Even though his floral and landscape windows exhibit a freer approach, Tiffany's delight in simulating effects of modeling and perspective were at odds with the tenets of progressive, two-dimensional design. | |||||||||||

| ********** | |||||||||||

| Tiffany and Bing's relationship lasted less than a decade—a period that generally coincided with the gradual rise and fall of the decorative arts at the turn of the century. It was undoubtedly a positive association for both men, bringing them prestige and many clients, perhaps even commercial profit. Both men were ambitious tastemakers, and if Tiffany was less adventuresome in his taste, especially in his later career, still his cautious balance permitted his business to flourish for another two decades. Yet commercial success is not everything. Looking back, the high point of this narrative occurred during the years just before the turn of the century when these men were closely associated, and when critics, for the greater part, were unaware of the significance of their undertaking. | |||||||||||

|

1. In writing this paper I was greatly aided by colleagues, not all of whom I can thank here. As always, with great skill Dr. Eliot W. Rowlands helped pare my prose and guided me to the mot juste. A special debt is owed to Dr. Graham Dry who was particularly generous in sharing his knowledge about turn-of-the-century Germany. My thanks also to Jean-Luc Olivié of the Musée des arts décoratifs, Paris. My work was greatly facilitated by the excellent exhibition catalogue prepared by Rüdiger Joppien: Louis C. Tiffany; Meisterwerke des amerikanischen Jugendstils (Cologne: Dumont, 1999). Not least of all, I thank my dear friends Yvonne and Gabriel P. Weisberg, who not only answered the many questions I posed about our mutual hero, S. Bing, but had the kindness to invite me to join this undertaking. 2. For the early history of the Bing family business see Peter van Dam, "Siegfried Bing 1838-1905," Andon, no. 10 (Summer 1983): 10-14; Gabriel P. Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing: Paris Style 1900 (New York and Washington: Harry N. Abrams and the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, 1986), 12-24. For Tiffany's early career, see Roberta A. Mayer and Carolyn K. Lane, "Disassociating the 'Associated Artists'; the Early Business Ventures of Louis C. Tiffany, Candace T. Wheeler, and Lockwood de Forest," Studies in the Decorative Arts 8 (Spring-Summer 2001): 2-36; see also the now out-of-date account in Robert Koch, Louis C. Tiffany, Rebel in Glass (New York: Crown, 1964), 9-69. 3. Koch, Rebel in Glass, 9, wrote that Moore met Bing in Paris in 1878 but this is unsubstantiated. 4. Rooms in the Havemeyer house had already been published well before Bing's visit; see "Modern American Residences," Architectural Record 1(January-March 1892): 383-90. 5. Favrile glass was first shown publicly in the spring of 1894; see the review in Art Amateur 31 (July 1894): 31; also Martin Eidelberg, "Tiffany's Early Glass Vessels," The Magazine Antiques 137 (February 1990): 502-15. 7. A word needs to be said about Tiffany's complex corporate structure. The primary firm, successor to the Tiffany Glass Company, was the Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company, founded in 1892. In 1893, the Stourbridge Glass company was incorporated; it was charged with making glass and then, later, with other 'hot' materials such as enamels and pottery. Although these were two separate firms, their stockholders were largely the same and the firms' activities were intertwined. For example, Stourbridge Glass was contractually obligated to make a designated amount of glass, and the Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company was obliged to buy it to produce windows, lamps, etc. The Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company officially changed its name to Tiffany Studios in late 1900, but the term 'Tiffany Studios' had already been in use since the mid-1890s as an umbrella term to cover the whole operation and the showroom. In 1902, the Stourbridge Glass Company was renamed Tiffany Furnaces, and that same year Tiffany Studios was absorbed into Allied Arts Company. Still further corporate changes occurred in subsequent years. 8. Bing, La culture artistique, 91. 9. See Bing's broadsheet announcing the intended opening of his new gallery on 1 October 1984; illus. Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, fig. 33. 10. Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 57, claims that "Tiffany had long encouraged" Bing to open "an art nouveau gallery." This unsubstantiated assertion gives too much credit to Tiffany. Conversely, Koch, Rebel in Glass, 75, claimed that around 1891 or 1892 "Bing was largely responsible for prodding Tiffany into producing a display for the forthcoming World's Fair...," but there is no evidence to support this. 11. André Bouilhet, "Exposition de Chicago: notes de voyage d'un orfèvre," Revue des arts décoratifs 14 (September 1893): 72-74. 12. Inv. no. 7853. The purchase was recorded on 20 January 1894, but none of the glass can be located. 13. Julius Lessing, "Kunstgewerbe," in Amtliche Berichte über die Weltausstellung in Chicago 1893 (Berlin,1894), 2: 802. 14. See Julius Lessing, "Electrische Beleuchtungskörper," Westermanns Deutsche illustrierte Monatshefte 77 (October 1894): 96-108. Bing used some of the line drawings from Lessing's report to illustrate an article of his own; see S. Bing, "L'Architecture et les arts décoratifs en Amérique," Revue encyclopédique 11 (December 1897): 1029-36. Apropos of these early lighting fixtures, see Eidelberg "Tiffanys frühe Lampen," in Louis C. Tiffany; Meisterwerke des amerikanischen Jugendstils, 215-28. The Berlin museum bought examples of favrile glass in 1893 (inv. nos. 96.87, 96.88) but these purchases were probably made in New York City. 15. Apparently England was not included within Bing's monopoly. The Tiffany & Company store in London sold favrile glass in that country. 16. Catalogue des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, dessins, gravure, architecture et objets d'art exposés au Champ-de-Mars le 25 avril 1894 (Paris: Société Nationale de Beaux-Arts,1894), 280: "Tifany [sic]– New-York. 494–Verreries." For Meier-Graefe's comment, see his "L'Art Nouveau. Das Prinzip," Das Atelier 6, no. 5 (1896): 3. 17. Louis de Fourcaud, "Les arts décoratifs aux Salons de 1894," Revue des arts décoratifs 15 (1894): 4. 18. Idem, "Les arts décoratifs aux salons," Revue des arts décoratifs 14 (June 1894): 378. 19. Paris, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, inv. nos. 7971, 7972. At the same time, Bing sold the museum a Chinese porcelain vase. 20. Paris, Musée d'Orsay, inv. nos. OAO 312, 315. The initiation of the sale antedates 8 November 1894, when the vases were presented in committee. 21. The advertisement appeared on the inside cover of an exhibition catalogue: 1re Exposition de H.G. Ibels (Paris: À la Bodinière, 5 November -15 December 1894). Their contractual agreement is significantly earlier than is supposed by Gabriel P. Weisberg in Weisberg, Edwin Becker, and Évelyne Possémé, eds., The Origins of L'Art Nouveau, The Bing Empire. Exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum; Paris: Musée des Arts Décoratifs; Antwerp: Mercatorfonds, 2004), 90. 22. When writing to Denis (see note below), Vuillard needed to define Bing as "le marchand de curiosités," a good indication that at this time the Nabis did not know him well. 23. Letter from Vuillard to Denis, 30 May 1894. Archives familiales de Maurice Denis, St. Germain-en-Laye. 24. Vallotton's Les Parisennes measures 128.5 x 60 cm (the tallest); Vuillard's Les marroniers is 110 x 70 cm.; Roussel's Le jardin is 121 x 91.4 cm. (the widest); Bonnard's La maternité is 70 x 68 cm; and Toulouse Lautrec's Papa Chrysanthème is the smallest at 59.5 x 40.5 cm. 25. Grasset's design was described as "gothico-japonais" by Louis de Fourcaud, "Les arts décoratifs aux salons de 1896," Revue des arts décoratifs 16 (1896): 220, but this applies to most of the artist's designs. A Grasset window showing a female cellist in a landscape and purportedly executed by Tiffany (illustrated in Dekorative Kunst 1 [January 1898]: 176) was instead made by Félix Gaudin, who generally executed Grasset's designs for leaded glass. 26. Letter from Bing to Denis, 30 October 1894, Archives familiales de Maurice Denis, St Germain; as cited by Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 50. 27. Their arrival in Paris was noted in a letter from Marcel Morot (Bing's assistant) to Denis, 18 April 1895, Archives familiales de Maurice Denis, St Germain. Missing were the Grasset window and five of the small ones by Sérusier, but this was compensated for in the 1896 Salon when the Grasset and two of the Sérusier windows were exhibited (under Tiffany's name); see Catalogue des ouvrages...1896, nos. 390-92. 28. Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 50, wrote "numerous cartoons" were sent to Tiffany and that he then chose those which he thought could be best translated into leaded glass; there is no evidence, though, that Tiffany had any such decisive role, nor is there evidence of supplementary, unexecuted designs from the French artists. 29. The essay first appeared in The Forum 15 (July 1893): 621-28. Its distribution in Paris is cited by Louis de Fourcaud, "Les arts décoratifs aux salons," Revue des arts décoratifs 15 (1894-95): 420. 30. Meier-Graefe, "L'Art Nouveau; Das Prinzip": 3. 31. Roger Marx, "Le Salon du Champs-de-Mars," Revue encyclopédique 5 (1 May 1895): 170. 32. René de Cuers, "Domestic Stained Glass in France," Architectural Record 9 (July-September 1899): 137-38. 33. Louis de Fourcaud, "Les arts décoratifs aux salons," Revue des arts décoratifs 15 (1894-95): 420-23. 34. The vitrine can be seen in several photographs of the gallery taken in 1895; see Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 72 (far right foreground), 73 (bottom left in both photos). 35. Letter of 4 August 1897 from Bing to von Scala in the Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna. Tiffany and his son had been in Europe in the summer of 1896, returning via Liverpool to New York on 12 September. Whether he went again in 1897 is not documented. 36. Catalogue des ouvrages ... 1896, no. 389: "Vingt-cinq vases en < 37. See Meier-Graefe, "L'Art Nouveau; Das Prinzip": 3. 38. L'Art Nouveau; deuxième catalogue (Paris: S. Bing, 1896), no. 813. 39. See "Moderne Kunstgewerbliche Ausstellungen," Dekorative Kunst 1 (September 1897): 30. 40. Henry Nocq, "Á Munich," Revue des arts décoratifs 17 (October 1897): 324. 41. Both the Copenhagen and Trondheim museums bought such lamps. One with a design of tulips on the base was illustrated in Alphonse Germain, "Quelques verriers," L'art décoratif 3 (March 1901): 243. 42. Catalogue des ouvrages...1898, no. 433: "Lamp électrique." 43. Similar presentation boxes were made for sets with Tiffany favrile salt dishes and spoons. One example is in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA, inv. no. 89.1431-6. Another is in the Iparmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest, inv. no. 53.618.1.1-4. 44. See Madeleine Octave Maus, Trente années de lutte pour l'art, 1888-1914 (Brussels: Librairie l'Oiseau bleu,1926), 203, 227; Werner Weisbach, "Die Ausstellung der Libre Esthétique in Brüssel," Kunstchronik, n.f. 9 (1897-98): 340; Gisbert Combaz, "Les arts décoratifs à La Libre Esthétique à Bruxelles," Revue des arts décoratifs 18 (February 1898): 60-61; Octave Maus, "Le Salon de La Libre Esthétique," Art et décoration 3 (1898): 101; "Brüssel," Dekorative Kunst 2 (April 1898): 39. 45. See in this issue, Marjan Groot, "Siegfried Bing's Salon de L'Art 46. Bing's success in Germany and lack thereof in France was noted at the time; see "Exposition Universelle; L'Art Nouveau Bing," L'art décoratif 2 (June 1900): 92-94. 47. See Offizieller Katalog der Internationalen Kunst-Ausstellungen (Dresden: 1897), 83-86. Ironically, Bing's display was presented as being representative of modern French interior decoration, although most of the rooms were designed by Belgians and the objects were very international in scope. 49. A numerical analysis shows the relative equality of the exhibitors. On exhibit were thirteen vases by Tiffany as well as four lighting fixtures, a metal pitcher, and a bell-push. Gallé was represented by sixteen vases, Dalpayrat and Lesbros showed eighteen ceramics, while Bigot had an impressive array of thirty-five examples. The frieze of glass mosaic that encircled Van de Velde's salon was designed by Georges Lemmen but was apparently not executed by Tiffany, nor was the decorative skylight. As might be expected, Wilhelm Bode, Kunst und Kunstgewerbe am Ende des Neunzehnten Jahrhundert (Berlin: B. und P. Cassirer, 1901), 108-11, was one of the few who commented on Tiffany's presence there. 50. "Verkäufe und Versteigerungen," Das Atelier no. 12 (1897): 13. 51. See Gustav E. Pazaurek, Moderne Gläser (Leipzig: H. Seeman, 1901), 38. 52. See the letter from Bing to von Scala, 4 August 1897, in the archives of the Museum für angewandte Kunst, Vienna. 53. [S. Bing], "Die Kunstgläser von Louis C. Tiffany," Kunst und Kunsthandwerk 1 (1898): 105-11. When this essay, translated into English, appeared in the Grafton Galleries 1899 exhibition catalogue (discussed below), Bing's authorship was specifically designated. 54. See "Wien," Dekorative Kunst 1 (1898): 135. 55. In 1900, Bing sold examples of Loetz glass to the Victoria and Albert Museum: inv. nos. 1296-1900 and 1305-1900. 57. "Verkäufe auf der VII. Internationale Kunstaustellung im Glaspalast in München," Das Atelier, no. 22 (1897): 14. 58. See Vera Varga, Glass and Radiance; Iridescent and Lustered Glasses from the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century to the 1910's in the Collection of the Museum of Applied Arts (Budapest: Budapest Museum of Applied Arts, 2000), 79-83, 126-30. The idea expressed at the turn of the century that Tiffany created twenty-nine of the works especially for the Budapest exhibition does not bear consideration. 59. See "München," Dekorative Kunst 1 (November 1897): 90-92; also "Ausstellungen und Sammlungen," Die Kunst für Alle 13 (1 June 1898): 286. 60. In regard to the first venue, see K.Schw., "Berlin," Dekorative Kunst 1 (February 1898): 232; also "Austellungen und Sammlungen," Die Kunst für Alle, 13 (15 January 1898): 125. For the second venue, see "Dresden," Dekorative Kunst 2 (May 1898): 76; also "Dresden," Studio 14 (1898): 287; "Ausstellungen und Sammlungen," Die Kunst für Alle 13 (1 July 1898): 301. 61. For example, see "München" Dekorative Kunst 1 (October 1897): 90; "Berlin," Dekorative Kunst 1(December 1897): 137; "Berlin," Dekorative Kunst 1 (February 1898): 232; "Dresden," Dekorative Kunst 2 (May 1898): 76; also Louis C. Tiffany; Meisterwerke des amerikanischen Jugendtsils, nos. 75, 83, 103, 119, 123. 62. Section des Beaux-Arts de l'Exposition Générale des Arts et de l'Industrie (Stockholm: 1897), 152. 63. Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, inv. nos. 75-81/1897; Trondheim, Nordenfjeldske Kunstindustrimuseum, inv. no. NK 255-1897. Joppien, in Louis C. Tiffany; Meisterwerke des amerikanischen Jugendstils, 24, did not see Bing playing a role here. 64. See, for example, Julius Meier-Graefe, "Französisches Mobiliar," Dekorative Kunst 2 (June 1898): 104-08; "Der Bing'sche Pavillon L'Art Nouveau auf der Weltausstellung," Dekorative Kunst 6 (December 1900): 488-93. 65. According to contemporary reports, many of these pieces were sold to Keller & Reiner of Berlin; see Meier-Graefe, "Französisches Mobiliar": 108. Det Danske Kunstindustrimuseum, Copenhagen, bought a Tiffany vase with a Colonna mounting (inv. no. 1048) from the Hohenzollern-Kunstgewerbehaus of Berlin. 66. The essentially tripartite division of the exhibition resembles Bing's staging at Dresden. A supplementary section included Japanese prints and Mogul miniatures, reminding us that Bing never gave up his original Orientalist interests. 67. In addition to making purchases at the Grafton Galleries exhibition, Friedrich Deneken of the Kaiser Wilhelm-Museum in Krefeld borrowed lamps by Tiffany and by Ambrosius Benson for an exhibition he staged at the Krefeld museum on the theme of electricity. See the letter from Bing to Deneken, 16 November 1899, archives of the Kaiser Wilhelm-Museum, Krefeld; also "Krefeld," Kunstgewerbeblatt, n.f. 11, no. 3 (1900): 53-54. 68. One of Tiffany's new electric lamps was shown in the April 1898 Paris Salon; see Catalogue des ouvrages ...1898, no. 433. 69. Frank Brangwyn's cartoons for Music and The Baptism of Christ were illustrated in Hippolyte Fiérens-Gevaert, "Franck Brangwyn," Art et décoration 5 (July 1899): 24-25. Walter Shaw Sparrow, Frank Brangwyn and his Work (London: Kegan Paul & Co., 1915), 214, 230, is extremely vague about the commission, and cites only Music and The Baptism of Christ. 70. Earlier, Bing had Brangwyn paint a frieze around the L'Art Nouveau store as well as two canvases, Music and Dance, for the interior. Bing also commissioned Brangwyn to design rugs, and showed his paintings as well. 71. Exhibition of L'Art Nouveau; S. Bing, Paris (London: Grafton Galleries, 1899), nos. 6, 9. 72. Youth Picking Eggplants (Morse Museum of American Art, Winter Park, FL) was not listed in the Grafton Galleries catalogue nor mentioned at the time of the exhibition, but its photograph appears in Charles Holmes, ed., "Modern British Domestic Architecture and Decoration," Studio 23 (Summer 1901): 39, where it is credited "By permission of M. S. Bing." Three other Brangwyn cartoons for windows—two related to the theme of Charity and all designated "By permission of M. S. Bing"—were illustrated in "Stained Glass Designs by Frank Brangwyn," Studio 16 (May 1899): 256-58. 73. Brangwyn's design was reused for advertisements in Art et décoration in 1899. Among other things, it proclaimed that Bing was "Agent général pour la Verrerie d'art de L.C. Tiffany." 74. The Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg bought two vases directly from Tiffany Studios (inv. nos. 1900.332, 1900.333) and, at the same time, it bought others from Bing (inv. nos. 1900.334, 1900.337, 1900.338). 75. See the discussion of the Tiffany window with ducks and iris below. 76. See, e.g., Louis C. Tiffany; Meisterwerke des amerikanischen Jugendstils, nos. 13, 23, 76, 81, 97, 98, 100, 114-15, 122, 126, 132, 135, 139, 141-43, 205-06, and passim. 77. Paris, Musée d'Orsay, inv. no. OAO 313. It and another favrile vase of approximately the same date were bought in 1901. 78. A similar opticut lamp shade was illustrated in "Moderne Beleuchtungskörper," Dekorative Kunst 1 (1898): 11. 79. Det Danske Kunstindustrimuseum, Copenhagen, inv. no. 1050. At the same time the Copenhagen museum was making substantial purchases from Bing; see Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 210-13. 80. Cited by Joppien in Louis C. Tiffany; Meisterwerke des amerikanischen Jugendstils, 26. 81. This design began running in the April 1900 advertising supplement of Art et décoration: n.p. 82. A new design by Georges de Feure with text emphasizing modern interiors appeared in the July 1900 issue of L'art décoratif, opp. 172, replacing the previous Brangwyn design. Nonetheless, when photographs of Tiffany glass and lamps were published in L'art décoratif, the public was still reminded that Bing was Tiffany's sole representative in Europe; see ibid. 3 (March 1901): 248. Similarly, the advertisement citing Tiffany ran in Art et décoration through at least the June 1901 issue. A new advertisement featuring a Colonna bookcase, but referring vaguely to "Objets d'Art," appeared in the December 1901 issue of Art et décoration. 83. The candelabra and lamp are illustrated in G.M. Jacques [Meier Graefe], "Un petit salon," L'Art décoratif 2 (April 1901): 23, 28. Also illustrated (ibid, 26) is a bowl with de Feure mountings, and while the bowl is supposedly of favrile glass, it appears to be a glazed ceramic, perhaps by Bigot. 84. The original Tiffany window is illustrated in "Some Examples of American Glass Work," Keramic Studio 44 (June 1900): 131. The screen by Delovincourt is illustrated in Jacques [Meier-Graefe], "Un petit salon": 27, but is incorrectly ascribed to de Feure; the attribution to Delovincourt was noted in the subsequent issue: "Rectification," L'art décoratif 2 (May 1901): 87. 85. See Gabriel Mourey, "George de Feure–Paris," Innen-Dekoration 13 (January 1902): 15; also Ian Millman, Georges de Feure 1868-1943 (Amsterdam and Zwolle: Van Gogh Museum and Wanders, 1993), 22, 88. 86. For this bookcase, see Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 167. 87. W. Fred, "Die Sektion Frankreich," Dekorative Kunst 10 (September 1902): 461. The subsequent illustration of the window designed by Vallotton suggests that this was one of the windows exhibited; see Dekorative Kunst 11 (November 1902): 54. 88. See Tiffany Studios, Tiffany Studios, Esposizione d'arte decorativa moderna, Torino 1902 (Turin,1902); Fritz Minkus, "Die erste internationale Ausstellung für moderne Kunst," Kunst und Kunsthandwerk 5 (1902): 443, 445, 449. 89. Letter from S. Bing to F. Deneken, 26 February 1904, archives of the Kaiser Wilhelm-Museum, Krefeld. Deneken had been hoping to stage an exhibition in Dusseldorf of various ceramic and metal wares borrowed from Bing, but Bing replied: "You cannot count on Tiffany glass for the Dusseldorf exhibition because all his vases have been returned to America." This may explain how Tiffany came into possession of two of the windows designed by Brangwyn: The Baptism of Christ and Youth Picking Eggplants. On the other hand, Bing may have kept some Tiffany glass, including pieces with Colonna mountings; see sale, Paris (Hôtel Drouot), Collection Art Nouveau Bing, 19-20 December 1904, lot 103: "Collection de verreries artistiques, comprenant des vases, aiguières, bouteilles, carafes, ornés de fleurs, feuillages ou d'irisations, partie montée en bronze." 90. See the Tiffany Studios advertisement in Town and Country (11 June 1904): 5. 91. Catalogue des ouvrages...1904, 35. 92. See Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 261-65. 93. Catalogue des ouvrages...1905, 38. This was entirely appropriate since after the death of his father in 1902, Louis became president of Tiffany & Company. 94. See Kunstindustrie und Kunstgewerbe (1913): 115; also Martin Eidelberg and Nancy A. McClelland, Behind the Scenes of Tiffany Glassmaking; the Nash Notebooks (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2001), 120. 95. Ibid, 96. While Nash witnessed Tiffany's habits firsthand only after 1910, Tiffany was equally susceptible to European design in his earlier years. 96. See the lettering around the rim of a glass and silver yachting trophy dated 21-23 June 1900; sold New York, Sotheby's, 4 December 1999, lot 376. 97. See Keramic Studio 2 (December 1900): 161. 98. For this exhibition, see "At the Tiffany Studios," New York Evening Journal (23 March 1901); "The Tiffany Glass at the Pan American," Keramic Studio 3 (June 1901): 31; Anna B. Leonard, "Exhibition of French Pottery at the Tiffany Studios," Keramic Studios 3 (August 1901): 82-83. Ironically, his father's firm, Tiffany & Company, had been selling the ceramics of Delaherche and Chaplet as far back as 1893; see Bouilhet, "Exposition de Chicago": 75. It is not clear how long Tiffany & Company continued this trade. 99. Examples of such pottery were still part of Bing's stock when the contents of his gallery were auctioned; see Paris (Hôtel Drouot), 19-20 December 1904, lot 97: "Collection de vases en grès flammès de Dalpayrat, Bigot, etc." 100. In that Tiffany Studios had been using ceramic bases made by the Grueby Faience Co., the adaptation of these French ceramics was a logical move. 101. A Dalpayrat vase of this same model was exhibited on a Gaillard cabinet in Bing's pavilion at the 1900 World's Fair; illustrated in Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, fig. 183. Also, Tiffany transformed a Clément Massier vase into a lamp which is now in the Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY, inv. no. 79.4.117. Tiffany had a number of Massier vases, but these may have come to him via Tiffany & Company. 102. See Eidelberg, "Tiffany Favrile Pottery," The Connoisseur 169 (September 1968): 55-61. 103. Clara Ruge, "Kunst und Kunstgewerbe auf der Weltausstellung zu St. Louis (II)," Kunst und Kunsthandwerk 7 (1904): 635. 104. Clara Ruge, "American Ceramics; A Brief Review of Progress," International Studio, 28 (1906): xxiii-xxiv; idem, "Die Kunstaustellungen der Saison 1905-1906," Kunst und Kunsthandwerk 9 (December 1906): 698-69, 702-03, 705; idem, "Amerikanische Keramik," Dekorative Kunst 14 (1906): 171-75.

|