The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

"Dieux et Mortels: Les thèmes homériques dans les collections de l'École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts de Paris" Emmanuel Schwartz |

|||||||||||

| At the entrance to the splendid Salle Melpomène of the École des Beaux-Arts, the visitor to Dieux et Mortels is handed an eight-page explanatory leaflet in which the goals of the exhibition are clearly and succinctly set forth: "The exhibition presented today can be approached in three ways: the visitor will follow, at one and the same time, the unfolding of the Trojan War (Iliad) and the voyages of Ulysses (Odyssey), the history of the teaching of art in Paris, and the history of the interpretation of Homer in France." | |||||||||||

|

The first general impression of Dieux et Mortels is a very good one: a handsome space subdivided into sections with brightly colored partitions (lavender downstairs, Wedgwood-blue upstairs), a high ceiling, mixed overhead natural and electric lighting, and exemplary wall labels. (fig. 1) The exhibition is unpretentiously didactic and pedagogically refreshing, presenting the visitor with a selection of straightforward Homeric themes, chosen first and foremost to narrate the story of the Iliad and the Odyssey. Beginning downstairs in the Salle Melpomène, the different sections are simply entitled: The Gods, Achilles, The Great Scenes (the most celebrated episodes from the Iliad), and The Tragedies of Andromache and Philoctetes. Then upstairs, in the Salle Foch, the survey of Homeric themes continues under the following titles: The Fall of Troy, The Voyages of Ulysses, and The Return to Ithaca. Midway through the Salle Foch the exhibition shifts to an examination of Homer's literary descendants, in both the classical world and France, with the following sections: The Adventures of Telemachus (scenes drawn from Fénelon's celebrated narrative of 1699), The Aeneid, and Parallel Cycles (secondary legends alluded to by Homer: Theseus, Jason and the Golden Fleece, Hercules, Prometheus). The exhibition concludes appropriately with a room devoted to Homeric Laughter. | ||||||||||

|

One of the most exceptional, and indeed most welcome, aspects of the exhibition is the impressive range of media displayed. (fig. 2) The Homeric themes are illustrated by a selection of large paintings, free standing sculptures, large sculptural reliefs, and small oil sketches generally paired with small, bas-relief sketches. (fig. 3) These works are mainly from the nineteenth century, but they include an important number of eighteenth-century paintings as well. On the end walls of each section hang prints from the sixteenth through the eighteenth century with Homeric or related subjects. Altogether, there are 148 works of painting and sculpture, and 94 prints. | ||||||||||

| All of the works of art presented have been chosen from the collections of the École. Since its founding in 1648, the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture has had a school; and from the beginning, the teaching at this elitist institution was structured around a series of anonymous competitions that culminated in the grand prix de l'Académie Royale. The contestants for the grand prix were assigned a theme from classical literature, which had to be interpreted in the contestants' respective media, during the allotted amount of time. The winner of this coveted prize was awarded a sojourn at the French Academy in Rome, during which he was expected to send regular 'envois' of his work back to Paris. With his final admission into the Académie, the new member had to present his fellow academicians with a morceau de réception, a painting or sculpture that demonstrated his learning, intelligence, and proficiency. In 1793, during the French Revolution, the Académie Royale and the grand prix de l'Académie Royale were abolished, but only a few years later, in 1797, the Prix de Rome was re-established. Each year throughout the nineteenth century, the winner of the Prix de Rome was granted five years of study at the Villa Medici, after which the painter or sculptor could fully expect to embark on a successful, official career. | |||||||||||

| Apart from a great collection of drawings, one of the finest in France, the collections of the École are comprised largely of paintings and sculptures that have competed in, and generally won, one of the school contests. In addition to the Prix de Rome, there were lesser competitions known as the petits concours, which included contests with assigned themes in history composition (sketches), facial expression, and full and half-figure painting. Over the years the École's holdings have been further enriched by gifts, from both the French State and private donors, of eighteenth-century grand prix and morceaux de réception. These donations are most notably represented in the present exhibition by David's Andromache Mourning Hector (1783), which usually hangs across the river in the Louvre. Finally, the École possesses a large collection of Italian and French prints, dating from the sixteenth century through the eighteenth century. These prints were assembled for the purposes of study, and were first made available to students in 1864 with the opening of the school's library. | |||||||||||

|

The decision on the part of the exhibition's chief curator, Emmanuel Schwartz, to include sculpture is especially commendable. As a result, the exhibition has offered an opportunity to rescue plaster sculptures languishing in the school's basement, and begin a long overdue restoration campaign. (fig. 4) Unfortunately, many of the plasters have been irreparably damaged, and Schwartz has been courageous to exhibit a number of statues in bad condition with missing limbs and battered faces. (The École's entire collection of sculpture is the subject of a separate new publication by Schwartz.) An earlier exhibition, in 1984, was limited to painting, and had no greater subject than that of the Prix de Rome. By giving the present exhibition a major literary theme, the organizers have come up with a very promising proposition, and the École's collections of art provide an excellent, even ideal, foundation for such an enterprising and original project. Furthermore, the Homer exhibition is an exemplary effort by museum curators to exhibit a large selection of a unique, permanent collection that would otherwise remain unseen in storage. By expanding the exhibition to include writers like Virgil and Fénelon, the curators have also given themselves the opportunity both to acquaint the visitor with Homer's literary legacy, and to present more of the École's collections. But perhaps most significantly, these student works of art demonstrate how essential classical culture was to the teaching of art in the past. The visitor cannot help but admire, with some nostalgia, an age in which a solid grounding in classical literature was simply taken for granted among all educated Occidentals. | ||||||||||

| In addition to narrating and illustrating the principal episodes of the Trojan War (Iliad) and the travels of Ulysses (Odyssey), the exhibition permits the viewer to trace, if rather roughly and incompletely, the stylistic and iconographic evolution of Homeric themes in art, from the Renaissance to the late nineteenth century. The exhibition begins, at least chronologically speaking, with prints after Italian sixteenth-century painters, especially Raphael, Giulio Romano, Penni, and Primaticcio. These Renaissance artists, in the words of Schwartz, were concerned above all with rendering the great humanity of Homer's gods and mortals: "a vision of Homer thoroughly imbued with grandeur, color. . . and an Italian eroticism that is both free and sensual."(p. 28) In France, the Ulysses Gallery at Fontainebleau, designed by Primaticcio in the mid-1550s, was the most elegant and grandiose visual expression of this Renaissance tradition. For two hundred years, Primaticcio's immense decorative cycle, comprised of fifty-eight scenes illustrating the voyages of Ulysses, was highly esteemed and constantly copied. The entire mannerist ensemble was destroyed in 1739, but fortunately, Primaticcio's courtly, graceful, and often sensual compositions were all carefully recorded in a series of engravings by Theodor Van Thulden. A complete set of Van Thulden's prints bound in an album is displayed hors catalogue in the exhibition. The optimistic, humanist spirit of Primaticcio is continued and developed in early works by the Carracci brothers, most notably in their scenes from the Aeneid, conceived to decorate the Palazzo Fava in Bologna (1585). These lively, early baroque decorations were especially admired by eighteenth-century French Academicians, who knew and studied the Carracci frescoes through a faithful series of engravings by Giuseppe Maria Mitelli (1634-1718). A large selection of the Mitelli prints is presented on the side walls of the exhibition. But it is beyond the scope of a review for a nineteenth-century art journal to consider sixteenth and seventeenth-century interpretations of Homer (and Virgil) at any length. For our purposes, it is enough to say that these decorative cycles represent the dominant vision of Homer in France until the mid-eighteenth century, when a series of progressively radical reforms were undertaken in an effort to disassociate the graceful and the sensual from the heroic in contemporary French history painting. Homeric themes proved to be essential to this reforming process, the inauguration of which is perhaps best summarized by Diderot: "Ovid in the Metamorphoses will provide painting with bizarre subjects; Homer will provide it with grand ones." | |||||||||||

| An important revival of history painting at the French Academy occurred in the 1760s with the introduction of three new educational directives: the introduction of moralizing Greco-Roman themes in 1762, the reading of Homer, and the study of antique statuary. In the Achilles section of the exhibition, two grand prix paintings of 1769, one by Pierre Lacour (1745-1814) and another by Joseph-Barthélémy Lebouteux (b. 1742), illustrate an early phase of this revival. (fig. 5) The two paintings, both depicting Achilles depositing the body of Hector at the feet of the dead Patroclus, effectively demonstrate how the new reforms at the Académie were accommodated to the prevailing artistic idiom of the time. For all their newly acquired grandeur, these scenes still display the loose diagonal compositions, the pretty pastel tonalities and diffused lighting, the operatic rhetoric and costumes, in short all the extravagance and artificiality of late baroque painting. | |||||||||||

| In the exhibition, these florid mid-eighteenth-century paintings by Lacour and Lebouteux constitute a vivid and constructive foil for surrounding Prix de Rome paintings by young followers of David executed during the first years of the new century. Three of these Davidian paintings are of particular note: The Wrath of Achilles (1810) by Michel-Martin Drölling (1786-1851), Priam at the Feet of Achilles (1809) by Jérôme-Martin Langlois (1779-1836), and Briseis Mourning Patroclus (1815) by Jean Alaux (1787-1864). (fig. 6) These comparatively stark scenes from Homer's Iliad all exhibit, with varying degrees of success, the virile severity and rigorously ordered compositions, the incisive lighting, somber, theatrical realism, and more archeologically accurate costumes and props that are the very hallmarks of David's austere, artistic revolution and his profound re-evaluation of Homer's epic narrative. | |||||||||||

|

Nearby in the same section hangs the most prominent of all these student works: Ingres' Prix de Rome of 1801, Achilles Receiving the Ambassadors of Agamemnon. (fig. 7) Achilles, seated at left, and Patroclus, standing at his side, have interrupted their singing to receive Agamemnon's ambassadors, who have come to plead with Achilles to rejoin the war. In this frequently reproduced and exhibited painting, Ingres works to attenuate David's philosophical stoicism, his compositional rigor and the hallucinatory plasticity of his forms. Light is becoming more evenly diffused, color more delicate and the action less dramatic, but above all, Ingres' painting manifests a new concern with surface design and linear rhythms. His new proposition is perhaps best summed up by the elegant nude figure of Patroclus, whose hip-shot pose initiates a sensual undulating contour that is playfully, and even symbolically, picked up and continued by the graceful counter-curve outline of Achilles' lyre. With this languid arabesque, Ingres declares his heretical independence from both David's art and his master's stern, sober, and moralizing reading of Homer. |

|||||||||||

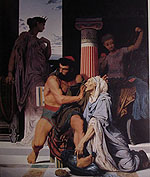

| The final section of the first floor, devoted to the tragedies of Andromache and Philoctetes, is the most successful of the exhibition. (fig. 8) David's Adromache Mourning Hector is immensely impressive in the big nineteenth-century gallery of the Louvre, but hanging alone in the apse of the Salle Melpomène, the painting is perfectly sublime. (fig. 9) "The most tragic painting ever inspired by Homer," the exhibition catalogue rightly claims, and "it is this tragic sentiment in art that has made the grandeur of the École." (p. v) This section of the exhibition also offers a rare opportunity to study student works by sculptors who will become major romantic artists. François Rude's beautiful, intense bust of Andromache (1812) is spectacularly installed on a pedestal beneath David's masterpiece. (fig. 10) The bust was actually modeled for a facial expression contest whose allegorical theme was "attention mixed with fear." Rude's Andromache, now attentive and fearful for the fate of her son, Astyanax, complements David's Andromache mourning her husband above. Displayed nearby is David d'Angers' handsome variation on the head of Laocoön, entitled La Douleur, after the 1811 facial expression competition for which it was executed. (fig. 11) In the subtle and sensitive modeling, especially around the brow, there are already hints of the great romantic portraitist and physiognomist David d'Angers will become. The tragedy of Philoctetes is the subject of James Pradier's splendid Prix de Rome relief of 1813. (fig. 12) Following the counsel of Ulysses, the Greeks abandoned their wounded and suffering warrior, Philoctetes, on the deserted isle of Lemnos. Later, during the Trojan War, Ulysses, accompanied by Achilles' son, Neoptolemus, returns to Lemnos determined to convince, or if necessary force, Philoctetes to hand over Hercules' bow, without which the Greeks are persuaded the war cannot be won. In Pradier's relief, Neoptolemus restrains Philoctetes, who is furious upon learning of Ulysses' new scheme, from killing his antagonist. The dramatic effect of the relief is perfectly in keeping with the teaching of the École, whereby the moment of action depicted must reveal and summarize the physical and moral nature of the characters represented. At left, the muscular, truculent archer, Philoctetes, physically tormented by an incurable wound and enraged by Ulysses' treachery, grabs an arrow from his quiver and prepares to shoot his adversary; at right, a reserved, cunning and cynical Ulysses calmly looks on, while in the middle, the lithe, spontaneous youth, Neoptolemus, swiftly intervenes to avert a tragedy.1 | |||||||||||

| It is instructive to compare Pradier's quintessential neoclassic relief with a small relief in the previous section by the young Barye. (fig. 13) Barye's sketch of 1823 depicts Hector before Paris and Helen, reproaching his brother for not participating in the war he has initiated. In this surprisingly powerful little bas-relief, Barye has reduced his composition to absolute geometric essentials, and modeled simplified, glyptic forms of imposing monumentality, to imbue his Homeric scene with a quality of timeless, heroic grandeur. These attributes, which we find again in Barye's mature works of the 1840s (Theseus and the Minotaure), are further enhanced in the present relief by Barye's abbreviated, generalizing modeling, which elevates his scene of Hector's confrontation with the irresponsible Paris to a classical world purified of the dramatic and psychological realism found in Pradier's relief. | |||||||||||

| Barye's relief is paired with an oil sketch by F-X Auvray (1800-33) of the same subject, date, and dimensions. Both sculpture and painting were executed for one of the École's history composition contests of 1823. These and other similarly related sketch pendants presented in the exhibition constitute one of the major revelations of Dieux et Mortels. The concours d'esquisse allowed young painters and sculptors an exceptional freedom in both the interpretation of their assigned themes, and in the handling of their respective media. Unlike Barye, certain other young artists, especially in the 1820s, saw the sketch competition as an opportunity to develop compositions with an intensity of expression and an energy of movement that would have been unthinkable in their more finished works at the École. Consequently, there are some unexpectedly bold and original experiments in composition, modeling, and brushwork to be discovered in the Homer exhibition. The majority of these sketches are hung upstairs in the Salle Foch, where perhaps the most courageous of these little works, a relief by Louis Desprez (1799-1870), Nisus and Euryalus (1820), is to be found. (fig. 14) The subject of Desprez's sketch is a rather obscure episode from the Aeneid. During the Italian campaign, two companions of Aeneas—Nisus and Euryalus—are ambushed in the forest at night by an enemy Rutulian patrol. Euryalus is taken prisoner by captain Volcens, while Nisus escapes. Later that night, Nisus kills two Rutulian warriors, and in a fury, Volcens kills Euryalus. Nisus tries to intervene and is killed in turn. It is the climatic moment of Nisus' intervention that Desprez narrates in his sketch. In this dramatically compressed, diagonal composition, all the figures have been crushed into a throbbing, interwoven design, where the charged and distorted forms of soldiers and rearing horse generate dynamic formal rhythms that convey both the extreme violence and the organic unity of this tormented vision. Although an oil sketch by Henri Serrur (1794-1865), executed for the same composition contest of 1820, is also of note, it is the sculptors who are more daring in their experimentation; one must look hard in the later painted sketches to find hints of the more advanced innovations of Géricault and Delacroix. | |||||||||||

| The genre of history landscape is well represented in the exhibition. Unlike the Prix de Rome for painting and sculpture, the Prix de Rome for landscape was established later, in 1816, and awarded only once every four years. The highly gifted Achille-Etna Michallon was the first recipient of the prize in 1817. Michallon worked brilliantly to revitalize the moribund neo-classical landscape tradition, and he was admired by his contemporaries as the great hope for the genre. Unfortunately, Michallon's career was cut short in 1822 when he died at the age of twenty-six. Stimulated by Michallon's example, some students at the École endeavored to compose landscapes and introduce effects of light, shade and atmosphere that would echo the drama, or enhance the mood and spirit, of their narrative themes. For other students an assigned theme was treated merely as a pretext for painting an indifferent, ideal landscape, in which no apparent relationship between subject and composition has been developed. The Homer exhibition includes Prix de Rome for the following years: 1821 (Jean-Charles-Joseph Rémond), 1825 (André Giroux), 1833 (Gabriel Prieur), 1837 (Eugène Buttura) and 1845 (Achille Benouville). (fig. 15) Of these heroic landscapes, Benouville's Ulysses and Nausicaa is the most successful. Ulysses has shipwrecked on the isle of the Phaeacians where he is rescued and clothed by the beautiful young princess, Nausicaa. Charmed and enamored by the older, mature Ulysses, Nausicaa leads him to the palace to meet her parents, who recognize in Ulysses an excellent husband for their daughter. But the brief idyll ends abruptly with Ulysses' decision to leave the island and recommence his travels. In Benouville's classical wooded landscape, Nausicaa and her servants make their way back to the castle. The princess looks back at Ulysses, who, following at a respectful distance, is engulfed by a deep shadow that already presages the unhappy denouement of her infatuation. | |||||||||||

|

In addition to the Prix de Rome landscape paintings, there are a number of smaller sketches executed for the École's landscape composition contest scattered throughout the exhibition. An oil sketch of 1832 by Paul Flandrin, also with the theme of Ulysses and Nausicaa, is particularly appealing. On a nearby wall hangs the Prix de Rome for history painting of the same year by Paul's better-known brother Hippolyte. Hippolyte Flandrin was Ingres' closest and most faithful student and protégé; he went on to become France's most celebrated religious painter of the nineteenth century. In Hippolyte Flandrin's Theseus Recognized by his Father of 1832, we already find the gravity of mind and spirit, as well as the palette, the shallow modeling, and the virtually hieratic figures that will distinguish Flandrin's later church decorations. (fig. 16) |

|||||||||||

|

Ingres' hold on academic painting continued throughout the Second Empire and beyond. Probably the most influential group of followers were the neo-Greeks, who emerged in the late 1840s, taking as their point of departure paintings like Ingres' much admired Antiochus and Stratonice of 1840. The easily recognized paintings by the neo-Greeks are characterized by an Ingresque precision of drawing, brilliant colors, slick brushwork, and an archaeological accuracy of historical reconstruction. With these academic painters, attention to the historical details of architecture, furnishings, costume, accessories and coiffeur takes precedence over any concern with instilling their works with an aura of heroic grandeur. Indeed, these often very accomplished, flashy, and entertaining pictures generally look more like anecdotal, genre paintings than true history paintings. Gérome is the best known of the group (The Cock Fight, 1847), but another major figure in the movement, Gustave Boulanger, is represented in the Homer exhibition by his Prix de Rome of 1849, the neo-Greek Ulysses Recognized by his Nurse Euryclea. (fig. 17) (Boulanger later painted the famous neo-Pompeian Rehearsal in the Atrium of Prince Napoleon of 1861.) Downstairs, a handsome watercolor drawing by Charles Garnier, the future architect of the Paris Opera, proposes an historical reconstitution of the facade of the Temple of Athena at Aegina. (fig. 18) Garnier's envoi de Rome of 1852 is a perfect complement for nearby neo-Greek Prix de Rome paintings by Henri Regnault, Thetis Bringing her Son Achilles Arms Forged by Vulcan (1866)—an exceptionally vigorous, over-the-top scene of Thetis attempting to coax her son off the dead body of Patroclus; Joseph Wencker, Priam at the Feet of Achilles Pleading for the Body of Hector (1876);and Louis-Edouard-Paul Fournier, The Wrath of Achilles of 1881. (fig. 19) |

|||||||||||

|

But with its large selection of art from the second half of the nineteenth century, the Homer exhibition becomes increasingly uneven. There are too many works from a period when history painting is in decline, and when artists are losing interest in figurative narrative and the heroic genre. And, there appear to be too many late academic works in which the tragic sentiment, "the grandeur of the École," is either totally absent, has grown stale, or become melodramatic. The students' responses to their assigned themes can be simplistic, unimaginative and immature; and in the exhibition catalogue, there is often a striking disparity between the loftiness of the authors' arguments and the modesty and mediocrity of some of the works cited and discussed. The organizers of the exhibition are well aware of both the intellectual and artistic limitations of some of these later works, and they rarely make exaggerated claims for them. However, the curators seem eager to put as much of their reserves as possible on view. One is torn between wanting to encourage the exhibition of these sorely neglected works, and objecting to the low level of quality and interest of the works presented. In the end, however, most visitors would probably agree that a more rigorous selection should have been made. |

|||||||||||

| The most ambitious goal of the Homer exhibition, and the one that is the most consequential from an art historical point of view, is the least successfully realized: the presentation of the history of the interpretation of Homer in France. This is an immensely rich subject with a far broader perspective than might at first be suspected. There is no single literary figure other than Homer who has inspired works of art that offer as comprehensive an overview of the evolution of narrative art in France, especially during the modern golden age, from the mid-eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century. During this period, Homer's poetry was constantly read, evaluated, and re-evaluated, and thus, Homeric themes are interpreted in narratives of remarkably wide-ranging quality, style, mood, and purpose. Perhaps most significantly, no other writer has played such a critical role in the history and development of narrative in French art. In other words, there have been French artists who have been motivated to invent a new art of narration, in great part by a desire to render more faithfully what they believed to be the true spirit of Homer's epic poetry. | |||||||||||

|

The problem here is that in order to demonstrate these arguments effectively, key works by major artists are necessary. Many student works in the exhibition are indeed important, some of the envois de Rome are major, and student efforts by lesser talents often illustrate the dissemination of the innovations made by greater artists; but pivotal works are indispensable if the survey is to be both representative and compelling. Here the question of loans imposes itself. Again, the collections of the École offer an excellent base, but the addition of fifteen to twenty key paintings, sculptures and print series, would have turned a highly informative and erudite exhibition into a more engaging and profound one. At this juncture, it seems both valid and appropriate to explore the interpretation of Homer in France, to mine further this rich vein, and consider briefly some key works with Homeric themes not included in the exhibition. |

|||||||||||

| French reviewers agree that a major Poussin is essential to the Homer exhibition.2 Poussin painted two fine autograph versions of Achilles Recognized by Ulysses (Boston and Richmond), though his direct literary sources for the paintings turn out to be Pausanias and Pliny, rather than Homer. In Apollo and the Muses (Prado), Poussin represents Homer and Virgil standing side by side conversing, and there seems to have been no fundamental distinction between the two in Poussin's mind. In spite of this, it is Poussin's insistence on the authority of the ancients that is capital for the later history of French narrative painting. (In Ingres' Apotheosis of Homer, it is Poussin who looks at the viewer and points back to Homer.) Furthermore, ever since the mid-seventeenth century, Poussin has been considered the intellectual and philosophical painter par excellence, and his paintings are the very foundation on which the French classical tradition was built. (In 1797, a new medal bearing the portrait of Poussin was designed for the winners of the Prix de Rome.) David's reforms are inconceivable without the example of Poussin; and if David's Andromache Mourning Hector is the most tragic painting ever inspired by Homer, it is also the greatest homage to Poussin.3 | |||||||||||

| Poussin and Claude are the undisputed masters of French classical landscape painting, but as far as the genre of nineteenth-century history landscape is concerned, Claude is the more influential of the two. Narrative themes in Claude's paintings are far from irrelevant as some historians, who see only pure landscapes in Claude's narratives, would have us believe. Though typically specializing in Virgilian pastorals, Claude painted two remarkable themes from Homer's Illiad: a pair of pendant pictures in the Louvre, Seaport with Ulysses Returning Chryseis to her Father and Landscape with Paris and Oenone. These two paintings are among the most effective demonstrations of how Claude composes settings, both architectural and natural, and exploits natural phenomena, different qualities of light, effects of light and shade associated with different times of day, and contre-jour to lend greater resonance, and even symbolic meaning, to the narrative of his literary themes. In the seaport view, Ulysses is seen in the middle ground returning Agamemnon's concubine, the Trojan maiden Chryseis, to her father's palace. The episode bodes ill because Agamemnon, having lost Chryseis, takes as compensation for his loss, the Trojan captive Briseis from Achilles. Consequently, the wrathful and vindictive Achilles withdraws from the war, and through his mother's intervention, persuades Jupiter to favor the Trojans over the Greeks in future battles. In Claude's painting, the sun sets behind Ulysses' ship, which dominates the center of the composition, transforming the vessel into a great ominous specter that foretells the unhappy events to come. In the Louvre pendant, the shepherd Paris is seated by a river with his beloved nymph, Oenone, but the sun has set, and lengthening shadows presage Paris' infidelity to Oenone, his rape of Helen, and ultimately the Trojan War itself.4 | |||||||||||

| David is the supreme reformer of the art and practice of narration in French painting. David's study of Poussin and ancient statuary, in conjunction with his reading of Homer, stimulated and propelled him in his progressive discovery of a virile, austere and stoic antiquity, which he brought to life through the parallel development of a striking physical, psychological and dramatic realism. The preponderance of Homeric themes in David's early paintings and drawings is telling, and his envois de Rome like the so-called Hector (Montpellier) and Patroclus (Cherbourg) are important steps leading up to David's first codification of his revolutionary narrative art in the tragic Andromache Mourning Hector. Either or both of these heroic academic nudes, remarkable composites of the real and the ideal, would have been a welcome addition to the Homer exhibition. | |||||||||||

| While there are a number of fine, representative eighteenth-century paintings in the Homer exhibition, there are no eighteenth-century sculptures with Homeric themes displayed in the École. Although the large collection of sculptural morceaux de réception in the Louvre does not include any pieces with Homeric subjects, the organizers of the exhibition have made exceptions for works with themes indirectly related to Homer in other instances. Meanwhile, the eighteenth-century sculptor with a real predilection for Homeric subjects, Clodion, is not represented in the exhibition. Clodion won the grand prix de la sculpture in 1759 and spent nine years, when the average was three, at the French Academy in Rome (1762-71). His terracotta, The River Scamander (1773, Sémur en Auxois), a rather obscure theme from the Iliad, is a superbly modeled, open pictorial composition from the baroque, allegorical tradition of river god sculpture. Several years later, in a terracotta treating the theme of Briseis Leaving Achilles (1780, Private Collection), Clodion created the sculptural equivalent of Vien's sentimental, classicizing, rococo compositions. However, the recent discovery of two exceptional terracottas by Clodion demands a serious re-evaluation of the sculptor's late oeuvre. The first of these two works, Meneleas Carrying the Body of Patroclus (1800, Boston) is a geometrically compact, sober, heroic composition, vitalized by a Davidian realism that heightens the tragic aura of the group. In a final, totally unexpected masterwork of great originality, Clodion chose to interpret an episode from the mythic, pseudo-life of Homer. Homer, now old, blind, and homeless arrives on the isle of Chios, where he suffers the final humiliation of being attacked by the dogs of a local shepherd (1810, Louvre). The expression of extreme physical and spiritual anguish on Homer's face is unforgettable, and the intensity of the emotion conveyed is unprecedented in either Clodion's oeuvre, or the work of his contemporary sculptors. This dramatic late composition has the aura of a very personal work that one is tempted to read as a metaphor for Clodion's own old age. In spite of numerous official commissions, and serious attempts to renew his art, Clodion remained the quintessential sculptor of the ancien régime, the unrivaled master of rococo insouciance and grace, who must have felt himself isolated, forgotten and even humiliated in the tumultuous, epic-making world of Napoleonic France. After the publication of André Chenier's 1819 Aveugle, which did much to popularize the myth of the blind, wandering Homer, romantic artists frequently interpreted the Homeric legend as a metaphor for the abandoned, ignored man of genius. | |||||||||||

| Toward 1800, the reading of Homer and the reassessment of his poetry greatly contributed to the emergence of a radical phase of neoclassicism that constitutes the most remarkable chapter in the history of interpreting Homeric themes in the visual arts. During this period, Homer was regarded as the greatest ancient poet, and he was especially distinguished from the more polite, refined Virgil. For many young artists, Homer was the ultimate primitive, and the discovery of his stripped, stark, telegraphic style, and plain, rude language prompted them to subject their own art to a drastic process of simplification and purification. The search for plastic equivalents of Homer's spare, "uncorrupted" verse led directly to the invention of an archaizing reductive art of pure outline, flattened volumes, minimal or no modeling, and airless, empty planar backgrounds. At the very center of this movement was the well-known sculptor and illustrator John Flaxman, whose illustrations of the Iliad and the Odyssey in a flat linear style, derived in part from the art of Greek vase painting, were first published in Rome during the 1790s. The immense influence of these engravings can scarcely be over estimated. While Flaxman's illustrations for the Iliad and the Odyssey are repeatedly reproduced in the catalogue for the Homer exhibition, they are curiously absent from the walls of the Salle Melpomène, where prints of less relevance are displayed in great numbers. This oversight is hard to understand in light of the fact that there must be many sets of the Flaxman illustrations in Paris libraries alone. | |||||||||||

| Of all French painters, Ingres was the one to play the most visible role in the extreme, purist movement, and he should be represented in the Homer exhibition by more than just his Prix de Rome of 1801. While Ingres was at the Villa Medici in Rome he painted two heavily stylized, anti-illusionistic masterpieces under the spell of Flaxman and Homer, the small Return to Olympus of Venus Wounded by Diomedes (1805) in the Basel Kunstmuseum, and the huge Thetis Imploring Jupiter in the Musée Granet in Aix. Either picture would have filled an important hole in the exhibition. Ingres' great academic manifesto of 1827, The Apotheosis of Homer is presumably too big to move to the École, but a later drawing of the same composition, also in the Louvre, would have been even more appropriate. In his 1865 drawing, Ingres pays a moving tribute to Flaxman (d. 1826) both by adding his effigy to the august company surrounding Homer, and by reproducing his celebrated illustrations for the Iliad and the Odyssey all along the frieze of the temple enclosing the composition. | |||||||||||

|

Much less well-known than the Ingres paintings are eight large bas-reliefs depicting scenes from the life of Achilles, carved by François Rude in 1823 to decorate the rotunda of the Château de Terwueren, near Brussels. Rude won the Prix de Rome in 1812, but with the fall of the Empire in 1815, he was exiled to Brussels for the duration of the Bourbon Restoration. In his Achilles reliefs (fig. 20), the future sculptor of the Départ on the Arc de Triomphe consciously distances himself from the motionless, meditative art of Flaxman as well as from the exquisite, mannered sinuosities of Ingres. Through the introduction of dynamic stylizations and dramatic movement, Rude charges the flattened, archaizing forms of his compositions with a virile, at times even brutal, force and energy. Particularly in his relief depicting the decisive battle between Achilles and Hector, Rude arrives at a boldly innovative variation of Flaxman's suave prototype—a potent variant that vividly conveys the barbaric heroics, the intense primitive emotions, the fury and tragedy of Homer's Iliad. The Achilles reliefs were destroyed by fire later in the nineteenth century, but fine original plaster casts of the reliefs are preserved in the Rude Museum in Dijon. One or two of these exceptional, forgotten reliefs by France's greatest romantic sculptor would have been a major addition to the Homer exhibition. The presentation of the Achilles reliefs would also have provided a unique opportunity to compare Rude's reliefs with Barye's exactly contemporary Hector Reproaching Paris. (fig. 13) Both sculptors propose powerful reductive styles, but Barye's bas-relief is sculptural and glyptic, where Rude's is pictorial and linear; Barye's narrative is characterized by qualities of timeless, abstract grandeur and monumental, classical detachment, while Rude's is impassioned and energized, primitive and violent. | ||||||||||

| We have already considered briefly the talented, short-lived painter Michallon, who won the first Prix de Rome for history landscape in 1817. In a later Homeric narrative, Philoctetes on Lemnos (Montpellier) of 1822, Michallon composes a forceful, heroic landscape, in the tradition of Salvator Rosa that dramatically conveys the suffering and savagery of the cruelly abandoned Greek archer. With his Philoctetes Michallon achieves a unity of subject, setting, and style greater than that to be found in any of the history landscapes presented in the Homer exhibition. The picture could have been hung to great advantage in the section of the exhibition devoted to the tragedies of Andromache and Philoctetes. | |||||||||||

| Though of a radically different temperament, Corot was a student and friend of the younger Michallon, and attempted himself occasional experiments in the genre of history landscape.5 Examples might include Hagar in the Wilderness (1835) and The Destruction of Sodom (1845), but Homer and Shepherd Boys (1845) is at once Corot's most successful heroic landscape and one of the most poignant evocations of the theme of the blind, wandering Homer. Here, Corot has beautifully attenuated the anguish, the drama, and the humiliation associated with Clodion's handling of the theme. Through the quality and angle of his light, and the gracefully rhythmic and harmoniously interrelated arrangements of his figures and trees, Corot imbues his scene with gentle feelings of melancholy, nostalgia, and ultimately, peacefulness. | |||||||||||

| The late academic painter, Henri Regnault, whose energetic, neo-Greek Prix de Rome, Thetis Bringing Achilles Arms Forged by Vulcan (1866), we have already mentioned, sent back as his first envoi from Rome a tremendously powerful Homeric composition, Automedon with the Horses of Achilles (1868, Boston). This astonishing neo-baroque painting, along with other dynamic pictures that followed, established Regnault as the great hope of the Academy, the savior who would revive and reinvigorate a moribund tradition. But Regnault, like Michallon, who had held a comparable position in history landscape painting, died at the age of 28, and had no real successors. | |||||||||||

| An older contemporary of Regnault's, Gustave Moreau, spent his life developing an entirely different, more radical response to the decline of French history painting. Moreau had attended the École des Beaux-Arts, but he left after losing the Prix de Rome, in 1849, to the neo-Greek painter, Gustave Boulanger. He is recorded as having reported to his father, "I want to make an epic art that is not an art of the academy."6 In his ambition to go beyond the narrative of traditional history painting, Moreau began a lifelong search for a more symbolic iconography. His research led progressively to the creation of a poetic, intensely personal, epic art, very far removed from the historical realism and the banal, anecdotal antiquity of the neo-Greeks. As an avid reader of the classics, including Homer, he painted several versions of Helen on the Ramparts of Troy, as well as a Glorification of Helen. By far the most important of Moreau's Homeric paintings, however, is The Suitors, a huge, hallucinatory re-enactment of Ulysses slaughter of Penelope's suitors. The largest and most imposing painting in the Moreau Museum, The Suitors was begun in the 1850s, enlarged in 1882, and left unfinished at Moreau's death. The painting is generally considered his masterpiece. In Moreau's feverish, morbid imagination, Homer's scene of carnage gives rise to a cruel sadistic dream-vision, where fantastic architecture, and transfixed inert figures—looking like so many pinned butterflies—are rendered in a miniaturist technique and rich jewel-like color that looks forward, both formally and spiritually, to the symbolist art of the 1890s. The Suitors has never left Moreau's house, but there are countless preparatory studies, watercolors and drawings that could have been borrowed for the Homer exhibition. | |||||||||||

|

The final section of the exhibition is a witty exercise in auto-derision. Beginning in 1893, the students at the École organized an annual, public, fancy dress ball known as the Bal des Quat'zarts. The students, joined by atelier models as well as other enthusiasts, dressed up in elaborate costumes imitating those found in celebrated history paintings, and cavorted wildly through the streets of Paris. In a very entertaining painting by Georges Rochegrosse (1904) (fig. 21), the Bal des Quat'zarts is seen nearing its conclusion, early in the morning, at the foot of the Champs-Élysées. In the uproarious tumult, an inebriated Roman Emperor is supported by a harem girl, a medieval courtier embraces a nude black model, an Egyptian Pharaoh professes love to an eighteenth-century lady, and a Japanese Samurai protests to a Spanish dancer (Lola Montès?), while figures from modern realist paintings mill about the crowd, all under the watchful eye of a perplexed gendarme. | ||||||||||

| From the other side of the room comes a great burst of Homeric laughter. In the sublimely irreverent caricatures for his Charivari lithographic series Ancient History (1841-43), Daumier wittily ridicules the heroes and heroines of antiquity, and the pompous, false academic tradition that continues to prop them up as paradigms of virtue, nobility, and heroic grandeur. With a humanity so much greater than the vast majority of the artists represented here can claim, Daumier gives us Helen abducting Paris, Achilles smoking a pipe in a rocking chair inside his tent, Patroclus polishing armor, Helen thumbing her nose at the triumphant Meneleas, and Ulysses and Penelope finally reunited in bed with Ulysses snoring as an adoring Penelope looks on. | |||||||||||

| In the end, Homer's true greatness may well be his unique universality; and the real tribute paid to Homer by French artistic genius may well be its perception and appreciation of this universality, constantly demonstrated throughout the rich and protean history of French narrative art. In the mid-eighteenth century, the reading of Homer first helped to revive an all but forgotten and ignored tradition of history painting; then it inspired David to subject this rejuvenated academic tradition to drastic reforms, and visualize a new narrative that permitted him to take history painting to sublime new heights of tragic expression. Distancing himself from his master, Ingres was in turn stimulated by Homer in his search for a rarer antiquity of cool sensuality and exquisite grace; while Rude and Barye developed contrasting, powerful reductive styles, one monumental and removed, the other primitive and dramatic, that brought them still closer, they believed, to the true spirit of Homer's poetry. Romantics found inspiration in the mythic life of Homer, and the blind old Homer became a symbol of the isolated, neglected modern artist. And, when the academic tradition had atrophied and lost its former grandeur, the greatest comic genius of French art invoked Homeric laughter to mock the ancients and attack a false antiquity. Finally, at least for our purposes, in his attempt to rescue history painting from the banality of historical realism, Gustave Moreau turned once again to Homer in an endeavor to transcend traditional narrative, develop a more symbolic iconography, and create a new epic art. | |||||||||||

| There is much to be learned from the Homer exhibition at the École des Beaux-Arts, especially with regard to the fundamental role played by classical literature in the teaching of art in Paris. The exhibition is an imaginative model, and one hopes eventually a stimulus to other museums and institutions with large reserves of art that are languishing in storage. At the same time, it is regrettable that the exhibition was unable to explore the more profound and vital aspects of the history of the interpretation of Homer in France. One comes away from this very informative and learned survey enlightened, but with the disappointing impression of having experienced too little of either the greatness of Homer or that of the French artistic genius. | |||||||||||

| Brooks Beaulieu Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France BrooksBeaulieu@aol.com |

|||||||||||

|

1. For this interpretation of the Pradier relief, see Jacques de Caso, Statues de chair : Sculptures de James Pradier (1790-1852). Exhibition catalogue. (Geneva : Musée d’art et d’histoire, 1985), 110-12. 2. Eric Biétry-Rivierre, Les Thèmes homériques dans les collections de l’École des Beaux-Arts : La fausse antiquité démasquée," Le Figaro, 19 October 2004. 3. See Richard Verdi, “Situation de Poussin dans la France et l’Angleterre des XVIIIe et XIXe siècles,” in Nicolas Poussin 1594-1665. Exhibition catalogue, Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, (Paris : Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1994), 98-104. 4. For this interpretation, see H. Diane Russell, Claude Lorrain 1600-1682. Exhibition catalogue, (Washington D. C.: National Gallery of Art, 1982), 148-49. 5. For Michallon and early Corot, see Peter Galassi, Corot in Italy, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1991), 59-60. 6. Jean Paladilhe and José Pierre, Gustave Moreau (Paris: Hazan, 1971), 10.

|