The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

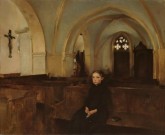

An Orphan in Church by Pascal-Adolphe-Jean Dagnan-Bouveret

A painting by the French painter Pascal-Adolphe-Jean Dagnan-Bouveret (1852–1929),[1] last seen in public in 1886, unpublished and never reproduced, was recently bought by a private collector in the United States, who has kindly allowed us to publish it in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide. An Orphan in Church (fig. 1) was originally acquired by New York collector Mary Jane Sexton Morgan (d. 1885), sometime after its completion by Dagnan in 1880. It is not known where she bought the painting, but it was probably at the shop of a New York contemporary art dealer. An Orphan in Church was not the only painting by Dagnan that Morgan owned; she also, in 1884 or 1885, acquired Violinist (1884), today in The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.[2]

Mary Jane Sexton was the second wife of Charles Morgan (1795–1878), who had made a fortune in railroads, shipping, and the iron industry. A former schoolteacher, she married Morgan in 1851 and put her husband’s money to good use by forming a first-rate collection of fine and decorative arts.[3] Unfortunately, she had only a few years to enjoy Dagnan’s paintings as she died in 1885. Early in 1886, her collection was auctioned off by the well-known New York auctioneer Thomas E. Kirby in a sale that took ten days[4] and brought in a whopping $1,205,090.42.[5] Beyond a fine collection of Chinese porcelains and a wide array of other objets d’art, the auction included a substantial collection of paintings, mostly by French nineteenth-century artists fashionable at the time.[6] Number 181 in the auction catalogue, Dagnan’s An Orphan in Church, was sold for 2,300 to one J. H. Bonham.[7] What happened to the painting during the next thirty-five years is not known with certainty but, by 1921, it was owned by John Lafayette Weeks, who may have inherited it from older relatives.[8] The painting remained in the Weeks family collection for the next ninety-three years until it was sold to its current owner, who, while allowing NCAW to publish it, wishes to stay anonymous.

Dagnan was twenty-eight years old when he painted An Orphan in Church. Despite his young age, he had already had a good deal of success as an artist. After entering the École des Beaux-Arts in 1869, he had studied for a few months with Alexandre Cabanel before moving to the atelier of Jean-Léon Gérôme. As a student he won several prizes, and at age 22 he began exhibiting at the Salon, selling a painting to the state in 1875.[9] Three years later, in 1878, he received a third-class medal;[10] that same year Dagnan and his friend Gustave Courtois left Paris to work in the Franche-Comté, Courtois’s native region.[11] Dagnan abandoned the mythological subjects he had painted up to that time to focus instead on subjects from contemporary peasant life. In 1880, his painting An Accident (fig. 2),[12] representing a village doctor bandaging the hand of a peasant boy, received a médaille 1ère classe at the Salon. An Orphan in Church was painted in the same year as An Accident. The two paintings have several characteristics in common: a focus on humble life in the French countryside, specifically, the Franche-Comté; indoor settings with deep perspectives, and a monochrome tonality. Indeed, Dagnan’s turn from mythological to contemporary subjects involved a change in style from the use of bright colors to a more muted palette.

Measuring 21 by 17 inches, An Orphan in Church is inscribed in the lower left “PAJ Dagnan-B/ Corre, 1880.” The inscription is important, as it not only provides the date but also the place where Dagnan painted it. The village of Corre is located in the Franche-Comté, a region where, as mentioned, Dagnan went to paint from 1878 onward and where he met his future wife.[13] Anne Marie Walter, whom he was to marry on October 11, 1879, in fact, originated from Corre, where the couple must have celebrated their wedding in the very church that is represented in An Orphan in Church.[14]

The church of Saint-Maurice, in the center of Corre, is a small one-isled Gothic building. The interior of the church is the setting for Dagnan’s painting, in which a little girl, dressed in black, sits in a pew holding a rosary. While the church interior was an important theme in Dutch and Flemish art of the seventeenth century, it did not become popular in France until the early nineteenth century, when François-Marius Granet refashioned the theme by giving priority to the human figures, often priests or monks involved in religious rituals, rather than to the spaces in which they were set.[15] The theme of the church interior was resumed in the middle of the nineteenth century by several Realist painters, including François Bonvin (1817–87) and Amand Gautier (1825–94), but in their work it is not ritual that is stressed but the role played by the church and religion in the lives of ordinary people. In many cases these Realist artists focus on poor and lonely people who come to the church to find shelter and solace. In Bonvin’s The Poor Men’s Bench: Memory of Brittany (fig. 3) of 1868, for example, two women are seated on the wooden bench at the periphery of the church, reserved, by law, for the poor incapable of paying for the rental of a pew.[16] Unable to see the altar and humiliated by their marginal position in the church, these women, nevertheless, devotedly read their missals or bibles, apparently finding consolation in religion.

Consolation also seems to be the essential theme of Dagnan’s painting in which an orphan has come to the empty church to commune (judging by the rosary) with the Virgin Mary. A postcard of the church (ca. 1925; fig. 4),[17] based on a photograph made some forty-five years after Dagnan completed his painting, shows a small altar dedicated to the Virgin left of the main altar, which would have been in front of the pew in which the girl is seated and could have been the focus of her intent gaze. By deliberately leaving the object of her attention out, however, Dagnan has created an image that is open-ended and the more effective for leaving it up to the beholder to imagine what she is looking at.

The little girl’s orphaned state is suggested by her black dress and by the fact that she is unaccompanied by an adult. Orphans, in the second half of the nineteenth century, were sometimes placed in orphanages but, more often, housed with family members or neighbors. In rare cases, older children were placed in domestic service.[18] Something of an orphan himself (he lost his mother at age six, was abandoned by his father, and raised by his grandfather),[19] Dagnan may have identified with the little girl and her feeling of loss and being lost. Her placement in the empty church, against the backdrop of a labyrinth of empty pews, effectively conveys a feeling of abandonment and insecurity.

The painting’s apparent simplicity and sobriety, its open-endedness and lack of anecdotal sentimentality set it apart from An Accident, which abounds in narrative detail. An Orphan in Church is a psychological study, focused on the state of mind of the lonely little girl. The architecture, more developed than in Realist church interiors like Bonvin’s The Poor Men’s Bench, supports the message of the painting. It is possible that An Orphan in Church, which is much smaller than An Accident, was a study for a larger work that was never completed. Perhaps it was inspired by the actual experience of seeing a girl in the small Corre church. But even if this was not the case, Dagnan certainly based his rendering of the interior of the church on careful study. He may have set up his easel inside the church; alternatively, he may have made careful preparatory drawings, though these are not currently known. It is even possible that he used photographs, though this practice, common in Dagnan’s paintings of the mid 1880s, is generally thought to have started after about 1882.[20]

The discovery of An Orphan in Church is important for several reasons. The painting is an early example of Dagnan’s new Naturalist style, inspired by his move to the Franche Comté.[21] It is also, as far as we know, one of the first paintings by Dagnan to come to the United States. The artist’s work would become very popular in the United States in the late 1880s and the 1890s, when works like An Accident, The Pardon in Brittanny (1886; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), and Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus (1896–98; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh) were bought by major American collectors like Henry Walters and Henry Clay Frick. The early presence of An Orphan in Church in the Mary J. Morgan collection indicates that American dealers, especially those in New York, had their finger on the pulse of what was happening in French art and were willing to take a risk with the works of young artists, for which they believed they could create a market.

Petra ten-Doesschate Chu

Seton Hall University

Petra.chu[at]shu.edu

I am grateful to Yvonne and Gabriel P. Weisberg for sharing with me the documentation they received from the collector. This article is also much indebted to Weisberg’s book, Against the Modern: Dagnan and the Transformation of the Academic Tradition (New York: Dahesh Museum of Art; New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2002).

[1] The artist was born Pascal-Adolphe-Jean Dagnan but later added his mother’s maiden name Bouveret in deference to his maternal grandfather, who raised him. In the remainder of the article, he is referred to as “Dagnan.”

[2] Number 81 in the Morgan sale catalogue, it was sold for $ 1,000 to William T. Walters. Morgan had acquired the painting from Gustav Reichard's Art Room in New York. It is now in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore under the title The Musician. See The Walters.org accessed January 19, 2015, http://art.thewalters.org/detail/24467/the-musician for a reproduction and the provenance of this painting. It is possible that Morgan bought An Orphan at Church from Reichard’s as well, though he may have acquired it from another New York dealer in contemporary art like Knoedler or William Schaus.

[3] See The Frick Collection, Archives Directory for the History of Collecting in America, s.v. “Morgan, Mary Jane,” updated November 18, 2014, accessed January 19, 2015, http://research.frick.org/directoryweb/browserecord.php?-action=browse&-recid=7040.

[4] Catalogue of the Art Collection Formed by the Late Mrs. Mary J. Morgan . . . . (New York: American Art Association, 1886). I have used the annotated copy in the William Randolph Hearst Archives of Long Island University, Brookville, NY, accessed January 20, 2015, https://archive.org/details/liu-31289009871502.

[5] For the proceeds of the sale, see Frick Collection, Archives Directory, s.v.“Morgan, Mary Jane.” A number of Morgan’s Chinese porcelains were bought by William T. Walters, including the famous “three string” peach bloom vase, for which Walters paid the unheard-of price of $ 18,000, a far cry from the $ 2,300 fetched by Dagnan’s painting. See Jan-Erik Nilsson, “The Morgan 'Three String' Peach Bloom Vase,” Gotheberg.com, accessed January 19, 2015, http://gotheborg.com/glossary/morganvase.shtml.

[6] The catalogue lists the names of 114 artists represented in the collection. The majority of the names are French, but the list also includes a number of artists of other nationalities, such as American, British, Dutch, and German.

[7] The price of the painting and the name of the person to whom it was sold are found in the Catalogue of the Art Collection in the William Randolph Hearst Archives.

[8] The latest member of the Weeks family to own the painting, John Kirkland Weeks, IIl, established the following provenance for the painting: between 1880 and 1886: Mary J. Morgan; sold at the auction of the Mary J. Morgan estate, New York, 1886 (partially illegible name on auction record, J. K. [Bonhau?]; 1886–88: John Lafayette Weeks (possibly); 1888–1921: Alexander Kirkland Weeks (possibly); 1921–51: John Lafayette Weeks; 1951–87: John Kirkland Weeks, Sr.; 1987–2000: John Kirkland Weeks, Jr.; 2000–2004: Mary M. Weeks (wife of John Kirkland Weeks, Jr.); 2004–2014: John Kirkland Weeks, IIl; 2014–present: current owner. See documentation of the painting in the possession of the current owner. I had access both to a Xeroxed page of the auction catalogue used by John Kirkland Weeks, III, and to the annotated catalogue in the Catalogue of the Art Collection in the William Randolph Hearst Archives from which I read the name of the person who bought the painting at the Morgan sale as J. H. Bonham.

[9] The State sent the painting, entitled Atalante, to the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire of Melun, where Dagnan had lived with his grandfather. For a reproduction, see “La vie des collections,” Melun.fr, accessed January 19, 2015, http://www.ville-melun.fr/Culture-Loisirs/Musee-d-art-et-d-histoire-de-Melun/Actualites/La-vie-des-collections.

[10] Weisberg, Against the Modern, 139.

[11] Ibid., 20.

[12] There is some question whether the painting exhibited at the Salon is the one that is now in The Walters Art Museum (reproduced in fig. 2). According to the museum website, it is, and the inscription on the frame, “Médaille 1ére Classe” seems to confirm it. But Weisberg argues that the Walters painting is an alternate version of the work exhibited at the Salon. See Against the Modern, 53. If that, indeed, is the case, the whereabouts of the original Salon painting are unknown.

[13] Ibid., 20.

[14] Ibid. Dagnan and his wife also bought a summer residence in Corre, which they owned from 1879 to 1886. They subsequently bought houses in Ormoy (1886–94), Raze (1894–97), and Quincey (1897–1926). Ibid., 21.

[15] As Stephen Bann has pointed out, while in the works of artists like Pieter Jansz. Saenredam tiny figures serve to enhance the impression of the spatiality of lofty Gothic interiors, in Granet’s paintings, such as his famous The Choir in the Capuchin Church on the Piazza Barberini, Rome (1808; Musée de Grenoble), the architecture serves to support the drama of the ritual being performed. See Stephen Bann, “Envisioning Rome: Granet and Gibbon in Dialogue,” in Roman Presences: Receptions of Rome in European Culture, 1789–1945, ed. Catharine Edwards (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 47.

[16] See Alphonse Karr, Les Guêpes, new ed. (Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1877), 5:131. Karr’s article was originally published in March 1844. His journal Les Guêpes was republished numerous times. The subject of the poor men’s bench had earlier been painted by the Belgian painter Charles de Groux (1825–70). His Le Banc des Pauvres (1854) is now in the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels. De Groux’s painting is a belated Romantic work that treats the theme in a manner that is more theatrical and anecdotal than the simple and sober approach of Bonvin.

[17] The message on the back of the postcard is dated May 23, 1925, which provides a date ante quem for the photograph.

[18] See Alain Bideau, Guy Brunet, and Fabrice Foroni, “Orphans and Their Family Histories: A Study of the Valserine Valley (France) during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries,” History of the Family 5, no. 3 (November 2000): 315. The Valserine separates the Franche-Comté from the Rhône-Alpes region.

[19] Weisberg, Against the Modern, 11–13.

[20] Ibid., 67.

[21] Ibid., chaps. 2 and 3, passim. Weisberg also mentions Dagnan’s contacts with the Franche-Comté artist Jules-Alexis Muenier and with Jules Bastien-Lepage as catalysts for his shift to Naturalism. Ibid., 21 and 61.