The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

The American West in Bronze, 1850–1925.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

New York, New York

December 18, 2013 – April 13, 2014

Denver Art Museum

Denver, Colorado

May 9 – August 31, 2014

Nanjing Museum

Nanjing, China

September 29, 2014 – January 18, 2015

Catalogue:

The American West in Bronze 1850–1925.

Thayer Tolles, Thomas Brent Smith with contributions by Carol Clark, Brian W. Dippie, Peter H. Hassrick, Karen Lemmey, and Jessica Murphy.

New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Distributed by Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2013.

192 pp.; 118 color illus.; chronology; artists’ biographies; checklist of the exhibition; selected bibliography; index.

$50

ISBN 978-0-300-19743-3 (hardcover)

The American West in Bronze, 1850–1925, which opened last December in the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is an exhibition of small, tabletop bronzes that carries a big wallop. Visually the works are beautiful—small-scale bronze sculptures that invite close inspection. Collectively, and individually, however, they communicate the sorrow and nostalgia for a way of life that was vanishing—images of Native Americans, the cowboy, the trapper, the mountain man, and the wildlife threatened with extinction.

Twenty years ago the mythology that these small works embody was ripped apart and exposed by exhibitions such as the Smithsonian’s The West as America (1991). Its revisionist view has become so widespread that the exhibition has garnered an extensive entry in Wikipedia. The organizers’ claims were that the artists and collectors helped promote the concept of Manifest Destiny (western expansion) at the expense of Native Americans, a viewpoint that has become orthodoxy. This orthodoxy, however, is not trumpeted by The American West in Bronze. Instead, the exhibition’s focus on small bronzes is, of necessity, narrow. At the same time the organizers successfully demonstrate how these images influenced popular culture and reference newer methodologies of memory and nostalgia. In this way the exhibition attempts, without ignoring the modern-day concerns with the destruction of Native American ways of life, to recast the myth of the West, claiming it not as a demonstration of white American hegemony but as a poignant and potent strain of American life

This viewpoint is underscored by several of these small sculptures that were replicated on a monumental scale as plasters at America’s world’s fairs and as civic monuments. For instance, Frederic Remington’s complex, four-figured, rootin’tootin’ Coming Through the Rye (shown only in Denver) of cowboys traveling on horseback with pistols blazing was reproduced for two expositions—the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, and the 1905 Louis and Clark Exposition in Portland, Oregon, both honoring the journey of Lewis & Clark from its start in St. Louis to its finish at the Pacific Ocean (fig. 1). Two decades later Alexander Procter, who was born in the West, was commissioned to create a monument called Pioneer Mother (1927) for Penn Valley Park in Kansas City, Missouri which he then reproduced quarter-size in bronze (figs. 2, 3).

In the exhibition this afterlife of the western bronzes was illustrated through archival photographs and images in the accompanying catalogue. Writing there, Brian Dippie, a Canadian historian, demonstrates how these images also invaded popular culture, reappearing as characters in dime novels, the movies, and even on coinage—the Buffalo nickel was designed by one of the most prolific of these artists, James Earle Fraser in 1913.

In New York the exhibit was organized thematically: the American Indian, the cowboy, wildlife and the settler, a structure that is expanded in the accompanying catalogue. The entrance to the exhibition opened with a large map of the Western territories and examples of some of the earliest representations of western imagery. Among the first of these manifestations were two works by New York artists: Henry Kirke Brown’s Choosing of the Arrow (1849) and John Q.A. Ward’s The Indian Hunter, (1860) (figs. 4, 5). Brown’s is an idealized representation of a young male Indian that reflects the influence of classical sculpture and European training. Ward’s sculpture, which was later enlarged and placed in New York’s Central Park was similarly inspired but his work is infused with a dynamic naturalism that came to characterize the later bronzes seen in this exhibition (fig. 6). The naturalism of Ward’s sculpture reflected an increased interest in realistic detail and greater familiarity with western imagery either by first-hand observation in the West or through study at newly established zoos and natural history museums.[1]

Once inside the main galleries, which were appropriately small in scale (fig. 7), one was introduced to the first of the four organizing themes—the American Indian. The sculptures in this section focused on their way of life often enveloped with an air of nostalgia or defeat. Hermon MacNeil, who traveled to Arizona to study the Hopi Indians first hand, captured an arresting image in his The Moqui [Hopi] Prayer of Rain or Snake Dance (fig. 8). What catches the eye is the running pose, flowing locks and the several snakes held by the Hopi priest, all of which are combined to create a remarkably fluid image. Among the most familiar of these Native American images is Fraser’s heart-breaking End of the Trail, which was a small scale replica of the monumental plaster displayed at San Francisco’s 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition (figs. 9, 10). Fraser grew up in the Dakota Territory and witnessed the opening up of the West to settlers, miners, ranchmen, and railroad men, all of whom impacted the lives and livelihoods of the Native Americans. For a contemporary American audience, Fraser’s image of an exhausted Native American, slumped over in his saddle fully encapsulates the despair experienced by the displaced indigenous peoples.

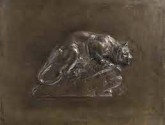

Complementing these fraught images of Native Americans were the depictions of the wildlife of the American West in the subsequent section. Some of these, most notably the bison, were at risk of becoming extinct. Exquisitely crafted, these sculptures reflect a renewed interest in Renaissance bronzes, the work of the contemporary French sculptor Antoine Louis Barye, and the tradition of the animalier. Buffalo and panthers, moose and black bears, these sculptures, like their figural counterparts also made a appearances in the public realm, sometimes the full-scale version preceding the table top edition. Two are relatively well known—one to ramblers in Manhattan’s Central Park, the other to pedestrians in Washington, DC, who cross the Dumbarton Oak Bridge at Q Street. Unlike most of the sculptures in Central Park that form a part of the formal landscaping, Edward Kemeys’s Still Hunt is found on top of a granite outcropping, a couching black panther ready to pounce (figs. 11, 12). In contrast, Proctor’s four monumental Buffalo are fully exposed on pylons at each corner of the bridge (figs. 13, 14). These two animals, in particular, which had largely disappeared from the western landscape, embody the same sense of nostalgia as that held for the Native American.

The third section contained the most popular and well known of all these Western bronzes, the ones of the American cowboy, the cavalryman, the mountaineer, most particularly the multi-figured, dynamic bronzes of the illustrator, painter, and sculptor Frederic Remington. His first bronze, The Bronco Buster is a tour de force in which a grizzled old man is determined to tame the rearing, wild bronco (fig. 15). Remington’s The Wounded Bunkie [bunkmate] in which a cavalryman, riding on horseback, rescues his wounded partner is another example of agitated sculpted narrative for which Remington was best known (fig. 16). The most complex of these story-telling bronzes is Coming through the Rye, a popular image that was based on an illustration Remington had created for a commentary “Frontier Types” written for Century Magazine by Theodore Roosevelt.

Roosevelt had an abiding affection for the Wild West, having traveled to the Dakota Territory in the early 1880s where he acquired a ranch that he maintained for nine years. Roosevelt’s love affair with the West went far beyond his role as land owner; over the next two decades he wrote four books on the West including Hunting Trips of a Ranchman (1885); Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail (1888, illustrated by Remington); The Wilderness Hunter (1893), and a four volume history of eighteenth century westward migration called The Winning of the West (1889–99) that detailed western exploration from 1769 to the early nineteenth century following the journey of Lewis and Clark.[2] Most importantly, Roosevelt’s experiences in the West shaped his personal philosophy of self-reliance, loyalty, and resolve, and fueled his conviction that the West was “the proving ground of American character.”[3] Aside from his many conservation efforts on behalf of the western landscape and wild life (during his presidency he established five national parks including the Grand Canyon), Roosevelt was also its historian and his West soon made way for the coming of the pioneers and settlers which was the culminating phase of westward expansion and the subject of the exhibition’s final section. One project by the Paris-based and French-taught Frederick MacMonnies’s Pioneer Monument for Denver, Colorado, encapsulates the coming-of-age, if not the conquest of the western territories (fig. 17). The MacMonnies is a large European-inspired fountain in the heart of the city. At the summit of this granite and bronze monument is a larger-than-life-size sculpture of the explorer, scout, and Indian fighter Kit Carson on horseback (a small bronze of the Carson image was included in the exhibition) in a pose that the co-curator of the exhibition, Thomas Brent Smith, likens to that of Napoleon in Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon at the Saint Bernard Pass (1801, Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna).[4] Placed along the fountain’s basin are three reclining, large bronzes; the hunter, the miner, and the pioneer mother, which by the early twentieth century had become the stock figures of western sculpture.

One failing of the catalogue is that little attention is paid to the contemporary collectors of these objects. One can only assume they would be prized and shown off by those also engaged in purchasing Italian Renaissance bronzes and small sculptures by the French artist Barye. How were they marketed? Were they sold directly by the artist or were there specific dealers that advised their wealthy clients? Who were these clients—East Coast financiers, West Coast railway men, stockyard men of the Midwest? Were they appraised in context of their Italian and French counterparts? Were there known connoisseurs of these statuettes?

My own introduction to Western art, one far different from Roosevelt’s experience, came several decades ago when I visited Jackson Hole, a beautiful Wyoming resort town on a broad plain, or hole, in the Rocky Mountains. The views are spectacular and include vistas of the Grand Tetons, a small range of mountains whose peaks often stand in for generic views of western landscape. As a city girl, I eschewed horseback riding, hiking trips, or a visit to nearby Yellowstone National Park (in the west, nearby is relative, Yellowstone is about 100 miles from Jackson Hole). Instead I wandered into the newly opened National Museum of Wildlife Art. Although an official sounding title, it was a modest-sized museum with good paintings by artists, some of whom were known to me. I had an introduction to the curator and after our tour she asked if I would like to see a temporary exhibition in adjacent galleries of the winners of the Prix de West. I nearly choked—Prix de West as in Prix de Rome, who could resist? These galleries, if memory serves me, were larger, with higher ceilings and were full of contemporary western art. I was speechless—I did not know a single artist and the work was unlike anything I had seen before in New York’s trendy galleries and high-toned museums. Instead I was confronted by outsized, hyper-realistic paintings of western mountain ranges, desert landscapes, and sculpted representations of cowboys and wildlife. The paintings were often done in overwrought color, while the sculptures were fashioned from intricate metal work in variegated patinas. The prices were as large as the artworks. I had no way of critically thinking about what I was seeing, but knew instinctively that west of the Mississippi there were thriving art markets for these works in Jackson Hole as well as Denver, Santa Fe, and points in between.

This experience was brought to mind when viewing American Bronzes of the West. These beautifully crafted table top bronzes are the distant cousins of what I saw in Jackson Hole, more Europeanized and genteel, more soundly crafted and refined, less celebratory and more elegiac than their mutant offspring. The works at the Met, unlike those in the Prix de West, embody a strong historic narrative that encompasses westward expansion following the Civil War, the fate of Native American, the disappearance of native wildlife, the role of world’s fairs, the establishment of zoos and natural history museums, the academic training of American artists, and the movies.

Overall this narrative, which these sculptures personify, spans a hundred years from the 1804 Lewis & Clark expedition to its centennial celebration in St. Louis’s at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase exposition. In between these two events an exceptional strand of the nation’s history was enacted. The Lewis and Clark expedition was ordered by President Thomas Jefferson and financed by the United States government. Its charge was to explore and map the land mass recently acquired from France beginning in St. Louis on the west bank of the Mississippi and extending north and westward to the Pacific Ocean.

Westward exploration and settlement was also the subject matter for our earliest writers. James Fenimore Cooper narrated eighteenth-century frontier life in New York in his series of five Leatherstocking Tales written between 1823 and 1841. Another New York writer, Washington Irving, after his return from many years in Europe, became so enamored of the American west that he journeyed there himself, a trip he documented in A Tour of the Prairies. He was then inveigled by the fur trader and millionaire, John Jacob Astor to write a novel, Astoria, that glorified Astor’s American Fur Trading outpost in Oregon. A few years later, Irving wrote the Adventures of Captain Bonneville, which was drawn from the maps and papers of the French-born West Point trained military officer who in the 1830s explored and surveyed the Oregon territory. These best selling books by Cooper and Irving bracketed the first hundred years of western history starting in the mid-eighteenth century on the shores of Lake Erie and extending to the Pacific.

In the Midwest, contemporaneous with the work of these novelists, there appeared a variety of studies of the Plains Indians including works by the geographer and ethnographer Henry R. Schoolcraft, who married a half-Ojibwa woman. He had been appointed Indian Agent for the territories of northern Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota where he and his wife collected and transcribed stories of the Ojibwa. The Schoolcrafts’ work, Algic Researches (1839), was later consulted by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow for his epic poem, “The Song of Hiawatha” (1855).

In addition to the writers, a number of painters traveled west to record Native Americans and its flora and wildlife. Prominent among them was George Catlin whose Native American portraits date from the 1830s when he traveled in what is now Minnesota, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, and North Dakota. Many of these portraits comprised his Indian Gallery, published as Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians in London in 1879. Prior to the Civil War others followed: Alfred Miller, Karl Bodmer, a visiting Swiss artist, John Mix Stanley, and the German-born Karl Wimar and Albert Bierstadt.

During the 1840s, expansion and exploration exploded with the 1845 Annexation of Texas and the 1846 Oregon treaty with Britain which included territory that is now the states of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana, and the 1849 Gold Rush. The culmination of the acquisitions of these territories was the publication of The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky Mountain Life, by the Harvard historian, Francis Parkman, serialized in twenty-one installments in Knickerbocker Magazine between 1847 and 1849.

The 1850s witnessed the first of the Indian Appropriation Acts, which established the creation of Indian reservations by the federal government. Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, westward expansion was controlled by federal legislation such as the Missouri Compromise (1820) and was the proximate cause of the Civil War. After the war this legislation was lifted and with the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, expansion became settlement.

The era following the Civil War was one of the most complex in the nation’s history—Reconstruction ended and Jim Crow laws took force in the South. At the same time, the railroad brought unprecedented wealth to enterprising capitalists from California to New York, with a stop over in Washington for a bit of scandal known as the Teapot Dome. At the same time, museums, libraries, and universities were brought into being by this wealth. Broad shoulders pushed aside the plights of the African-American and the Native American through such legislation as the 1871 Indian Appropriation Act. A few years later there was a showdown between federal troops and the Katota, Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes at Little Bighorn known as Custer’s Last Stand. These western wars came to a tragic conclusion with the Battle at Wounded Knee in 1890 with the Army’s massacre of the Sioux on the Pine Ridge Reservation near Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota.

Not all Americans were heedless of the fraught conflicts between the Native Americans and the United States Army. In 1881 Helen Hunt Jackson (better known as the author of Ramona) wrote A Century of Dishonor: A Sketch of the United States Government’s Dealings with Some of the Indian Tribes, which brought the plight of the Native American to a large audience. The decade of the 1880s also saw the conversion of western mythology into popular entertainment with the traveling shows of Buffalo Bill Cody and Wild Bill Hickok. Two turn-of-the-century world’s fairs, Chicago’s 1893 World Columbian Exposition and St. Louis’s 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, transformed the western experience into history. Large scale images of bison panthers, bears, and lions by Kemeys marked the terminus of several bridges that spanned the fair’s lagoons and canals while Proctor’s images of pairs of elk, moose jaguars, and polar bears were placed on the end posts of bridges. Many of these nearly extinct animals were now to be found in the nation’s new zoos and natural history museums. The best known marker of the decline of the western experience was pronounced at the fair by the historian Frederick Jackson Turner in his essay “The Significance of the West in American History.” His “frontier thesis” purported that westward expansion had become emblematic of the democratic spirit, yet with the closing of the frontier, the first period of American settlement (1492–1892) was over as the forces of the modern industrial corporation replaced the spirit of individualism of frontier life. At the beginning of the twentieth century the St. Louis Exposition brought western history full circle by celebrating the 1804 journey of Lewis and Clark. With its extravagant Beaux-Arts architecture and formal gardens, as well as sculptures of cowboys and Indians by Remington, Alfred Weinman, and Solon Borglum, St. Louis became the Gateway to the West not as the starting point for adventure, but as the disseminator of civilization.[5]

What does it mean then that the exhibition’s small bronzes could also be found enlarged at world’s fairs and as civic monuments? They are certainly more than souvenirs; to categorize them is such is to demean the quality of their craftsmanship and to undermine their status as art. That a number of these tabletop bronzes had both a public and private life speaks to their critical importance in the early twentieth century and underscores the new connections Americans had to Western lands, their history, and mythology. Hovering over them is the shade of Theodore Roosevelt who, more than any other American, articulated the meaning and the importance of the West for the nation at the turn of the twentieth century. It is no coincidence then that he was immortalized, along with George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln, in Gutzon Borglum’s iconic western landmark, Mount Rushmore National Memorial (1929–41) in the Black Hills of South Dakota. It is not often noted, but the careers of all four presidents were beholden to the political philosophy of Manifest Destiny: Washington through his wresting the land from the British, Jefferson by his legislation to acquire from the French the large land holdings west of the Mississippi, Lincoln for safely securing the settlement of the West from conflicts over slavery, and Roosevelt who detailed this American epic in his book, The Wining of the West. Nor should it be surprising that Mount Rushmore’s creator, Gutzon Borglum, along with his brother Solon, were among the sculptors and myth makers featured in The American West in Bronze exhibition. This then, the story of western expansion and its meaning for America at the turn of the nineteenth century, is the big wallop that can be teased out from these small treasures.

Sally Webster

Professor of American Art, Emerita

Lehman College and the Graduate Center, CUNY

Salweb38[at]gmail.com

[1] The first American zoo opened in 1860 in New York’s Central Park; Philadelphia’s in 1874 and the largest, the Bronx Zoo, opened in 1899. The American Museum of Natural History in New York opened in 1877.

[2] Published between 1889 and 1899, the four volumes of The Winning of the West are: volume 1, “From the Alleganies to the Mississippi, 1769–1776;” volume 2, “From the Alleganies to the Mississippi, 1777–1783”; volume 3, “The Founding of the Trans-Alleghany Commonwealth, 1784–1790”; volume 4, “Louisiana and the Northwest, 1791–1807.”

[3] Public Broadcasting System, “New Perspectives on the West,” 2001. Accessed August 26, 2014 http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/people/i_r/roosevelt.htm

[4] Thomas Brent Smith, “Settling the West: Fearless Men and Strong Women,” in The American West in Bronze 1850–1925 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013), 133.

[5] Among the large-scale sculptures on the St. Louis fairgrounds were, in addition to Remington’s Coming Through the Rye, Adolph Weinman’s Destiny of the Red Man, and Solon Borglum’s Cowboy at Rest.