American Art History Digitallysponsored by the Terra Foundation for American ArtImpossible Garden: A Contemporary Artist’s Digital Engagement with Women Artist-Naturalists of the Long Nineteenth Century and BeyondProject Narrative

by Emma Steinkraus

Emma Steinkraus is a visual artist and assistant professor of fine art at Hampden-Sydney College. Her paintings and installations use strategies of juxtaposition and layering to explore ecology, gender, and the history of science. Her current project, Impossible Garden, highlights the contributions of women artist-naturalists through an immersive wallpaper collaged from reproductions of their work. Steinkraus’s work has been exhibited recently at galleries including 1969 Gallery (New York, NY), Deanna Evans Project (Brooklyn, NY), Poker Flats (Williamstown, MA), and Field Projects (New York, NY). She has been awarded artist residencies at the Studios at MASS MoCA, the Wassaic Project, the Blue Mountain Center, and the Vermont Studio Center, where she is a Helen Frankenthaler Fellow. In 2020, she was an Eliza Moore Fellow for Artistic Excellence at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation. Her work can be found on her website or on Instagram at @emmasteinkraus.

Email the author: woodemma[at]gmail.com

Citation: Emma Steinkraus, “Project Narrative,” in Emma Steinkraus, with Carey Gibbons and Allan McLeod, “Impossible Garden: A Contemporary Artist’s Digital Engagement with Women Artist-Naturalists of the Long Nineteenth Century and Beyond,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 20, no. 3 (Autumn 2021), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2021.20.3.29.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Editor’s Introduction|Interactive Feature|Interview|Project Narrative

Project Narrative

Impossible Garden is a research-based art project that explores the contributions that historical women made to art and science through their illustrations of nonhuman species. The project includes a wallpaper collaged from reproductions of flora, fauna, and fungi illustrated by women; paintings based on the lives of women artist-naturalists; and this digital art history project, which is adapted from the wallpaper. Although my work for Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide (NCAW) only consists of the digital art history project, I was encouraged by the editors to provide context for the NCAW project, as well as insight into my artistic process, through a broader discussion of Impossible Garden.

The Wallpaper

Like many art projects, Impossible Garden took a circuitous path. In 2018, I stumbled upon work by the baroque Italian painter Giovanna Garzoni (fig. 1). I had been painting animals and her work immediately resonated with me (fig. 2). Her funny, charming, affectionate paintings captured some of the delight that I felt around nonhuman nature. Why had nobody told me about her?

Fig. 2, Emma Steinkraus, Pallas’s Cat, 2018. Acrylic on paper. Private collection. Image courtesy of Emma Steinkraus.

As I began researching Garzoni, a whole world of other historical women who painted nonhuman species started to emerge. The search terms “women botanical art” and “women historical scientific illustration” seemed to crack a secret code. After years of searching for women in art history and finding only the same handful of names, a new door had opened.[1]

That summer, I spent two weeks at an artist residency in Ireland called Cow House Studios. While there, I started batting around the idea of making a wallpaper out of women’s botanical and natural history illustrations. I created big, complicated folders on my computer’s desktop, sorting their work into subject categories like “nests” and “ferns.”

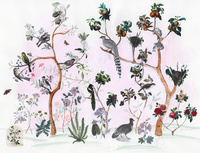

I began printing out the images I had collected and making collages by hand, arranging the birds and foliage into trees (fig. 3). After a few attempts, I felt dissatisfied. The printed images often came out the wrong scale. I kept pasting images down only to realize they would be better somewhere else. I wanted to have a sunrise gradient in the background, but it was painstaking to paint neatly around all the detailed elements. I put the project away.

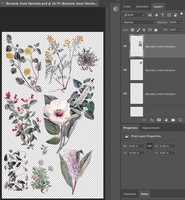

Six months later, I started toying with the idea of the wallpaper again. This time I used Adobe Photoshop. Slowly, I found a process that worked: I built it tree by tree. I began by dragging related images into Photoshop (for example, illustrations of apples or pinnate leaves). Using selection tools and layer masks, I removed the illustration’s background and extraneous elements (fig. 4). I kept each illustration on a separate labeled layer, so that I could easily resize, rotate, or relocate it.

Once I had a selection of illustrations to work with, I arranged the individual parts until they suggested the form of a tree (fig. 5). On a new layer, I used digital paint tools to sketch a trunk and branches. When I was happy with the overall form, I projected the trunk onto Stonehenge paper and traced it out. Then I painted each trunk by hand and scanned the finished product back into Photoshop. Once the trees were complete, I digitally painted the rolling ground and gradient sky, populating both with additional reproductions of flora and fauna illustrated by women artist-naturalists (fig. 6).

At this point, in mid-2019, I had been working on Impossible Garden on and off for a year, but it still felt like a nascent, evolving project. I had never made a wallpaper before and had no clue how to print or display what I was making. I spent that summer experimenting at two artist residencies, the Blue Mountain Center (BMC) and the Good Hart Artist Residency. I printed out a prototype of the wallpaper on a tiny ink-jet printer and wheat pasted it to the wall of my studio at BMC. At Good Hart, I installed a section of wallpaper that I had printed out in sections onto full-sheet Avery shipping labels. In January 2020, I installed a full-scale prototype that way in the gallery at Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia (fig. 7).[2]

Fig. 7, Installation view of Emma Steinkraus, Wall Garden: A Work in Progress, The Gallery at Brinkley Hall, Hampden-Sydney College, Hampden-Sydney, 2020. Wallpaper printed on Avery shipping labels. Image courtesy of Emma Steinkraus.

Seeing the wallpaper at scale helped immensely, but I needed to find a more professional solution to printing. I got lucky: the Oak Spring Garden Foundation (OSGF) awarded me a 2020 Eliza Moore Fellowship, which made experimenting with professional printing feasible. OSGF also hosted me as an artist in residence three times over the course of that year, and a substantial amount of my research happened in their Special Collections Library. By early 2020, the wallpaper was largely done and I turned my attention toward the paintings in the Impossible Garden series, many of which were completed in the OSGF’s studio spaces. I am incredibly grateful for their support.

The Paintings

The paintings emerged as a response to the wallpaper. I began the research for the wallpaper because I wanted to celebrate and spotlight the contributions of women artist-naturalists, but as I studied their work, new research questions arose. It was impossible for me not to notice how much easier it was to find examples of work by white, wealthy European women, nor could I avoid how many of them had participated in colonial projects. I couldn’t continue to use the archive without thinking critically about the structural forces that had created and preserved the archive we now have.

To better understand the archival record, I needed to engage with scholarship on race and colonialism. I am grateful for the creative, interdisciplinary scholarship of writers like Saidiya Hartman, Lisa Lowe, and Londa Schiebinger, which has helped me see some of the interactions between colonialism, race, gender, and natural history more clearly.[3]

Fig. 8, Emma Steinkraus, Evil Pioneer, 2021. Oil and photo transfers on canvas. Private collection. Image courtesy of Emma Steinkraus.

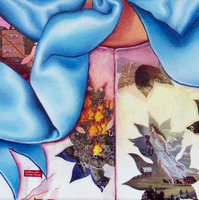

While the wallpaper celebrates the achievements of women artist-naturalists, the paintings grapple with the complexities of their individual lives within the larger sociopolitical systems that shaped them. Each painting combines detailed portraiture with photo transfers that form patterns on the women’s clothing. The transfers inventory the nuanced ways different women abetted and resisted patriarchal constraints, environmental exploitation, and colonialism. For example, the transfers in Evil Pioneer (fig. 8) draw connections between the social and ecological violence wrought by white settlers on the North American prairies through the juxtaposition of nineteenth-century imagery—including John Gast’s widely reproduced painting American Progress (1892), which personifies manifest destiny as a white woman, and archival photographs documenting the extermination of bison—with contemporary images, like screenshots of the Dakota Access Pipeline and photographs of wildfires in 2020 (fig. 9).

Like many of the paintings in this series, which I discuss in the extended interview, Evil Pioneer responds to the research for the wallpaper in personal, associative ways. It is not a portrait of a specific historical woman. Rather, it is a response to the overwhelming presence of colonialism throughout my research and to the specific forms of colonialism embodied within my own history as a white woman in the United States.[4]

Each painting begins with compositional studies or preliminary drawings (fig. 10) and a Photoshop mock-up. After I have decided on a basic composition, I make an acrylic underpainting on canvas. Then I photograph the canvas and upload the image into Adobe Photoshop. In Photoshop, I map out a plan for the photo transfers, uploading and arranging the images that I want to include. Then I print them to scale and transfer them to the canvas.

Fig. 10, Emma Steinkraus, Preliminary drawing for Evil Pioneer, 2021. Colored pencil on paper. Collection of the artist. Image courtesy of Emma Steinkraus.

My transfer process is done using acrylic medium. I coat the front of a laser-printed image with matte medium and use a squeegee to adhere it to the canvas. After it is dry, I use a wet sponge to dampen and peel off the paper until only the ink is left trapped on the surface. It’s a process that results in scratches and gaps that contrast with the smooth, carefully painted passages. This integration of large-scale acrylic-medium photo transfers and highly detailed painting is, as far as I know, unique to my work, although it is certainly inspired by artists like Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Robert Rauschenberg, who use a slightly different solvent transfer process.

Once the transfers are complete, I work up the rest of the painting in oil. The finished paintings are detailed, densely referential, and rendered in a distinctive high-key palette. Works from this series have been exhibited in 2021 in group shows at Deanna Evans Project (Brooklyn, NY) and Poker Flats (Williamstown, MA), and in a solo presentation in the project space at 1969 Gallery (New York, NY), which layered a selection of paintings over the wallpaper (fig. 11; vid. 1).

Fig. 11, Installation view of Emma Steinkraus, Impossible Garden, Project Space at 1969 Gallery, New York, 2021. Printed wallpaper and paintings with oil and photo transfers on canvas. Image courtesy of 1969 Gallery.

The Digital Art History Project

At the College Art Association’s annual conference in 2021, I presented a paper called “Lady Botanizers: A Survey of Pre-20th Century Women in Scientific Illustration” in the session “Science, Gender, and the Decorative in the 18th and 19th Centuries.” Carey Gibbons, the digital art history editor at NCAW, reached out afterward and invited me to consider creating a digital art history project. I talked through the options with Gibbons and NCAW’s executive and managing editors, Isabel Taube and Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, and we decided to collaborate on an expanded online version of the wallpaper that viewers could scroll through, zoom into, and click on to access the original source images. NCAW also suggested including an extended interview about the project, a project narrative, and profiles of select artists based on my research.

Once the shape of the project was determined and had gone through peer review, my first step was to create two new components for the wallpaper. Over the course of working on the original Adobe Photoshop file, I had continually discovered new artists. By the summer of 2021, I had found work by 166 women, but when I finally counted up all the artists in the wallpaper, I realized that I had only managed to included work by fifty-seven of them. Revisiting the digital file for NCAW gave me an opportunity to incorporate work by twelve new artists through the creation of two rose bushes. After the bushes were complete, I rearranged all of the trees and other files to form a balanced composition.

The next step was to label and create citations for the 274 individual collaged elements included in the file. All of the collaged elements in my Photoshop file were labeled with the name of the artist, but I had not saved any additional information about my source images. This meant that I had to track down all of my original sources once again, combing through books, internet databases, and reverse image searches. Compounding the difficulty of the attributions was my lack of postgraduate training in academic research. I hadn’t formatted a citation since my undergraduate years, and I am very grateful to Gibbons and NCAW’s copyeditor, Cara Jordan, for their extensive help with this aspect of the project.

Tracking down my sources was time consuming but provided a welcome reminder of the many institutions that made this project possible. I am especially grateful for Wikimedia Commons, the Biodiversity Heritage Library, and the National Agricultural Library of the United States Department of Agriculture. Two-thirds of the images in Impossible Garden were found through those three sources. This project simply would not exist without the efforts of all those who contributed to their open-access internet archives.

Once I had a labeled master file, I sent it to Allan McLeod. McLeod used the OpenSeadragon plugin to convert my Photoshop file into a navigable digital format, making many thoughtful design choices along the way. It was McLeod’s insight, for example, to use simple colored rings as indicators of click points. McLeod also made it possible to interact with Impossible Garden in new ways by designing a sidebar that allows viewers to group together works by a specific artist, by the artist’s nationality, or from a range of dates. Furthermore, McLeod realized my vision for hyperlinks in the artist profiles that accompany some of the original source images, enabling easy navigation between the different artists featured in the project and creating a sense of community among the women that crosses time and space.

Writing was the last important step in my collaboration with NCAW. Completing the extended interview, individual artist profiles, and this project narrative took much more time and effort than I expected. As a visual artist, I rarely write for an academic audience. Articulating my thinking and process in written language was truly a challenge, but one that I undertook with the hope that through this project more people will come to experience some small part of the fascination and importance these women artist-naturalists have held for me.

Notes

[1] My search, it should be said, was highly unsystematic. Based on my anecdotal experience, the majority of English-language information about women artists before the twentieth century is devoted to about ten artists: Sofonisba Anguissola (ca. 1532–1625), Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614), Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–after 1654), Judith Leyster (1609–60), Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750), Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807), Elisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun (1755–1842), Rosa Bonheur (1822–99), Berthe Morisot (1841–95), and Mary Cassatt (1844–1926).

[2] I used Avery shipping labels because they are inexpensive, easily accessible, and can be printed on a home printer. The downsides are numerous. They’re finicky to install and can’t be easily reused. They bubble and peel off in humidity yet also leave a residue that took multiple bottles of Goo Gone to remove. Unless you are a scrappy artist on a budget (which I was and largely still am), I recommend that any artist interested in creating a wallpaper work with a professional printer. I used Worth Higgins & Associates for the version installed at 1969 Gallery in New York, and they did a fantastic job.

[3] There are still many works by these scholars that I have yet to read or fully process. Some specific texts that impacted my thinking include Saidiya Hartman’s essay, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (June 2008): 1–14; and her book, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2019); Lisa Lowe’s The Intimacies of Four Continents (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015); and Londa Schiebinger’s Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004).

[4] Many of the women in Impossible Garden directly participated in European colonialism: in India (Lena Lowis, Olivia Tonge, Elizabeth Gwillim, Diana Ruth Wilson), Australia (Harriet Scott, Louisa Atkinson, Elizabeth Gould), Tasmania (Louisa Anne Meredith), and Suriname (Maria Sibylla Merian, Johanna Herolt, and Dorothea Graff). Others, like Sarah Stone, lived in Europe but based their illustrations on specimens collected under colonial rule. Still others, like Agnes Chamberlin and Mary Vaux Walcott, participated in the expansion of white settlement in the United States and Canada.