The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Australia’s Impressionists

National Gallery, London

December 7, 2016 – March 26, 2017

Catalogue:

Australia’s Impressionists.

Christopher Riopelle, ed., with an introduction by Tim Bonyhady, and with contributions by Allison Goudie, Alex J. Taylor, Sarah Thomas, and Wayne Tunnicliffe.

New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

128 pp.; 70 color illus.; bibliography.

$30.00

ISBN: 9781857096125

Australia’s Impressionists: by using this title the National Gallery’s curators Christopher Riopelle and Allison Goudie, and collaborators at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, have conscientiously separated this exhibition, its aims, and its outcomes from those of the Australian Impressionism exhibition held in 2007 at the National Gallery of Victoria. The difference between Australia’s Impressionists and Australian Impressionism or Australian Impressionists as an exhibition title may seem slight, but in making Australia take possession of Impressionism, the nomenclature matters.[1] The National Gallery’s curators at once announce their intention to appeal to the public with that key word “Impressionism,” while simultaneously disrupting persistent tendencies to conflate Impressionism with mid- and late-nineteenth-century France. Australia’s Impressionists sets out to pry apart Impressionism and France, by proclaiming the Impressionists in Australia to be the cosmopolitan equals to all the many artists painting in this idiom in France, England, the United States, and elsewhere around the world. This studied interest in the translation of Impressionism worldwide coincides with the National Gallery’s recently reworked mission. As announced by the introductory catalogue essay:

In recent years the National Gallery in London has set out to trace the lineaments of this evolving engagement with landscape painting, the questions it poses about the relationship between art in the cosmopolitan centre and the rise of national art movements in the most distant reaches of its orbit. Further, what role did this process of assimilation and adaptation play in the spread of Modernism? . . . Recently the National Gallery has expanded its mandate from the commitment to collect, display and study European painting; it now addresses painting further afield, works that, broadly speaking, fall within the European representational tradition but which may have been created elsewhere in the world. . . . In the future, visitors to Trafalgar Square will see an increasingly diverse display of international modern art (14–15).

Australia’s Impressionists thus supports the National Gallery’s conscientious critical shift to include global and transnational histories in its institutional remit. The National Gallery has promised that in the future it will include art produced, shown, and circulated across oceans, continents, and borders, albeit art that still “fall(s) within the European representational tradition.” (That caveat will be crucial to keep in mind.) More, it has underscored the need to study the local and the global in tandem.

Such a transformation in the mission of the National Gallery has had real ramifications on the exhibition under review here. The transnationalism of Australian artists Charles Conder, Tom Roberts, John Peter Russell, and Arthur Streeton—their ties to educational outlets and exhibition networks in Paris and London, inspiration by European or Euro-American artists, and co-option of painting en plein air—has been shot through with questions as to the emergence of national identity and landscape painting on the island continent.[2] On the exhibition’s walls and in the slim but beautifully illustrated catalogue, Australia’s Impressionists asks what it meant to be Australian and what constituted an Australian school of art in the late nineteenth century. At least in part, the answer to the latter question may lie in these artists’ determination to paint Australia’s cityscapes and landscapes en plein air in a palette that captures the natural environs: the white of its sand, the blue of its seas, and the pink of its soil.

Across the National Gallery’s three rooms (four counting the room dedicated to a film on the exhibit) and more than thirty paintings, Australia’s Impressionists narrated this story of the globalization and localization of Impressionism. The first room, entitled “The 9 By 5 Impression Exhibition” after the exhibit that launched Impressionism in Australia in 1888, displayed a set of intimately scaled paintings on box lids (measuring nine inches by five inches) by Conder, Roberts, and Streeton.[3] The introduction to the catalogue notes that these artists, upon setting sail for England and France, discovered only disappointment in “Europe’s academies [which were] hardly more exciting than the ones they had left behind” (13). Evidence of their time in London may be seen in Roberts’ small paintings of Trafalgar Square and the Thames; to the trained eye, the latter will likely recall paintings of the Thames by Whistler and Monet.[4] On his return to Australia, Roberts promptly launched the 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition in a rebuke of those academies. That vanguard artists started an alternate exhibition in opposition to academic institutions should scarcely surprise us. Still, the catalogue’s synopsis of the Australian academic education and exhibition system has ensured that readers understood the specific reason(s) for these artists’ rebellion.

Surrounded by their original wooden frames that still bear traces of metallic paint and, in the delightful instance of Conder’s Dandenongs from Heidelberg, a painted tendril reminiscent of the decorative frames of Whistler, these small paintings scintillated on the Gallery’s cool gray walls (fig. 1). Filtered through a lens of purple and lilac and painted in delicate brushstrokes, Streeton’s Hoddle Street, 10 pm here seems more like a quiet small town than the bustling urban metropolis that was Melbourne circa 1888. Melbourne could boast that it was the second most populous city in the entire British Empire (fig. 2). An expansive boulevard, Hoddle Street has been represented as emptied of traffic and occupied by a single cab and occasional, darkly painted passersby. Around this street scene, other nine-by-five-inch landscapes painted by Conder and Roberts on these slim box lids could be seen. Such a format makes for a panoramic view of the landscape, as though it was seen through eyes stricken by the harsh glare of the sun. Little wonder then that in the late nineteenth century, Impressionism in Australia came to be called “glare aesthetic” in a reference to the way dust shimmers in the dry heat of the Australian sun.

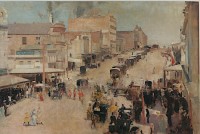

Compared with the quietude of late-night Hoddle Street, on the opposite wall, Roberts’ Allegro con brio—Bourke Street, West bursts with the rhythms of daytime Melbourne (fig. 3). In his title, Allegro con brio, Roberts has tied his art to that of Whistler, whose work he had seen in London at the 1884 Notes-Harmonies-Nocturnes exhibition. Packed with sketchily painted people (some of whom are little more than blue outlines) and crowded with horse-drawn cabs extending to the horizon, the broad boulevard of Bourke Street has been shown framed by storefronts and lined with telegraph poles and streetlights. In a witty commentary on the rapid transformation of modern life spurred by technological innovation, Roberts has painted a telegraph pole cutting through the street front canopy of “Dunn Collins Booksellers” stenciled on the side of a building. The new telegraph technology cuts through old print technology, Roberts implied. His crowds scurry to escape the blaze of the midday sun that suffuses this scene with dusky pinks and corals, and seek shelter beneath parasols and in the shade beneath store awnings, as well as cool relief from an ice cart being driven down the boulevard. A tricolore waves from a storefront—an allusion to the cosmopolitanism of this place as French émigrés apparently set up shop in Australia. Despite Roberts’ documentation of the city as having an international community and an active commercial center, Melbourne nevertheless resembles a frontier town, new but dusty.

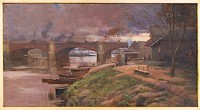

The transformation of Melbourne from small town to modern metropolis may further be seen in Streeton’s Between the Lights, Prince’s Bridge (fig. 4). Prince’s Bridge captures the modern infrastructure of the iron and stone bridge, but also that glimpsed through its arches: plumes of purple-gray smoke from factories spew forth into the twilight sky and blinking city lights may be seen in the background. Such allusions to modernity contrast starkly with the quaint farmstead à la Jules Bastien-Lepage that immediately meets the eye. Soon this farmstead will be swept away with the outward expansion of Melbourne.[5] Between the Lights straddles the fine line between rural and urban and between naturalism and Impressionism in its treatment of that topic. Though this first room effectively surveys the urban topography of Melbourne and Sydney—other paintings shown here depict train depots and docks—visitors would benefit from a map pinpointing exactly where these artists worked: Did they all congregate in one or two neighborhoods? What is the radius in which they painted? How were Melbourne and Sydney organized and zoned? And what is the connection between these streets and current planning and infrastructure of these cities?

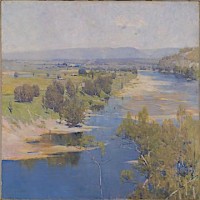

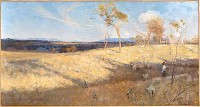

From metropolitan Sydney and Melbourne located on the coast, the exhibition’s second room, “National Landscape,” transports visitors to the Australian interior, which underwent an equally rapid transformation due to the demand for rail lines connecting people, products, and places. The size and scale of these pictures—the exhibit’s largest—match the expansiveness of the Australian landscape (fig. 5). Within these landscapes, visitors encounter “the resilient and hard-working pioneer men (usually) of the bush—stockmen, drovers, shearers, wool-carters, gold-miners and other rural laborers—who came to occupy the increasingly large and ambitious canvases produced in the period” (46). Those who visitors did not encounter, and whose presence has been all too conspicuously scrubbed from these painted records of the landscape, were the Aboriginal peoples who populated Australia before and after the arrival of British settlers. Inquiry into the presence and absence of Aborigines—central to any exploration of nationhood, identity, and representation in art—may uncomfortably push Australian Impressionism into the realm of the political. Yet the presence and absence of these populations seems so important to making Australian Impressionism into more than pretty pictures painted en plein air.

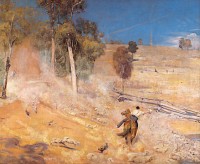

Streeton’s brush deftly transforms cattle and sheep ranches into poetic representations; his titles, The Purple Moon’s Transparent Might and Still Glides the Stream and Shall Forever Glide, indicate as much (figs. 6, 7). Roberts’ brush equally transforms shepherds and laborers into heroes in dramatized, albeit romanticized, epics of man versus nature. The National Gallery documented the harsh realities faced by the settlers who came to make Australia into a modern nation, but how modernization depended on the colonization and marginalization—politically, economically, and culturally—of Aboriginal peoples, and the exploitation of natural resources there, has been sidestepped. Australia’s modernization must not be separated from its colonization by these same settlers. Roberts’ Fire On! records the pitiful death of a worker due to a dynamite blast used to burrow a rail tunnel through the Blue Mountains (fig. 8). A casualty of modernity and its demand for more modes of transportation, communication, and interconnectedness, the worker being carried by his mates from the tunnel shaft seems small, insignificant compared to the nature that surrounds this scene. The hardness of the rock-strewn hillside and the attendant difficulty of making Australia modern has been communicated via a series of rectangular strokes that build solid layers of rock, encrusting the painted surface like the crust of the earth. Roberts’ equally dramatic A Breakaway! shows a flock of sheep that, in their haste to slake their thirst, trample a sheepdog and nearly topple their mounted shepherd (fig. 9). Leaving a wake of dust in their rush to the water hole, the sheep are reduced to balls of woolly fluff identifiable by their heads, hindquarters, and tips of tails, and indexically referenced by smudges and dabs of white across the painted surface. Such marks communicate the rapidity of their race down the slope, while the aridity of the landscape has been matched by Roberts’ overall dry application of paint that has cracked with time.

From these scenes of intense life-and-death drama, the exhibit turns to the coast, where Conder, Roberts, and Streeton all worked. In a pleasant trio of their paintings, curators Riopelle and Goudie demonstrate the dialogue between these artists. Of the three, the most innovative is Streeton’s Blue Pacific with its portrayal of picnickers on the rugged sandstone cliffs that undulate across the picture plane (fig. 10). A sand shovel, discarded fruit peels, and especially a toy boat belonging to the holiday-makers on the cliffs above playfully echo the real ship seen in the swath of cobalt blue below. Compared with Streeton’s dramatic scene of the coast, Conder and Roberts, in keeping with their Impressionist practices, set their easels side-by-side outdoors to paint Coogee Bay (figs. 11, 12). From their perch on a dune, seated behind a patch of scrubby trees, Roberts and Conder captured the white sand beaches with subtle variations reflecting their individual interpretation of nature.

On the opposite wall, the exhibition surveys John Russell’s post-1900 work in and around Belle-Île, an island off the French Breton coastline (fig. 13). Whereas Conder, Roberts, and Streeton each paint holiday-makers in their beach scenes, Russell situates his viewer alone before the sea, a loneliness that heightens the emotional intensity of his series. And whereas Conder, Roberts, and Streeton immersed themselves in Australian landscapes, documenting the world around them, Russell immersed himself in France’s landscape and the world of European Post-Impressionism there. The inclusion of Russell, as indicated by a wall panel, was intended to raise “the question of what it meant to be an Australian Impressionist, and [to raise] issues of national identity as they relate to Impressionism in its international context.” The most dramatic of the six scenes of Belle-Île, Coucheral Soleil sur Morestil (Sunset at Morestil) portrays the crashing of waves on rocks so evidently worn and eroded by the constant churning of the sea (fig. 14). These rocks reflect the play of light across their slippery surfaces. Russell has pushed and pulled pinks, oranges, and carmines, slashes of indigo and cobalt, and drips of white across his own painted surface to form this rocky outcrop, while frenzied strokes of white, blue, and green form the ebb and flow of the sea. Russell records the violence of nature versus nature to communicate the sublime—this, then, is a starkly different type of violence than that depicted by Roberts with the wrecked body of the worker.

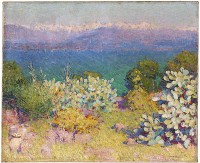

An émigré to France, Russell’s oeuvre recalls that of late Monet, Gauguin, and van Gogh, and perhaps even Matisse in its similarly bright colored palette and depiction of spatial ambiguity. In the Morning, Alpes Maritimes, from Antibes has been painted in stripped bands of color that, with his varied brushstrokes, lend texture and space to this scene (fig. 15). The topmost painted band signals the most distant space; the lowest painted band, the closest space. Within that lowest and closest band, distance and space are further shown through the variegated brushstrokes that lend texture to the plants. A place that Monet frequently painted, Russell’s Antibes fittingly demonstrates the multiple types of global circulation at stake in this exhibition: the circulation of Impressionism as a style and set of practices, dissemination of Impressionist artworks (French, Australian, and otherwise), and international travel and relocation of Impressionist artists (French, Australian, and otherwise).

On rare occasions, Australia’s Impressionists needed to better contextualize Australian art circa 1889 to 1900. Impressionism, so it would seem, sprung forth fully formed on the island continent in 1888, the centenary of British settlement and one year before the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle. Though curators note the former date as important (and cite the 1901 Federation of Australia’s six colonies—New South Wales, the Northern Territory, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria, and Western Australia—as similarly crucial to understanding art and national identity), the potential importance of 1889 to the transnational history of this art has not been thoroughly explicated. It would be useful to know whether these artists were present at or even participants in the 1889 Exposition Universelle, where they may have seen the Centennale and its survey of French Impressionism.

Streeton’s Golden Summer, Eagleton traveled the international exhibition circuit (fig. 16). From Australia, it went to the Royal Academy in 1891, and then on to the 1892 Paris Salon, where it received accolades. But which Salon? The Société des Artistes Français? The Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts? Or, less likely, the Indépendants? One suspects the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, which welcomed artists from outside of France, but no real clarification has been offered. His decision to enter an official exhibition would seem to mark a critical departure from his exhibition praxis in Australia circa 1888, when he, Conder, and Roberts mounted the 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition in opposition to Australian official exhibitions. (Once more, it would be useful to understand what official exhibitions were held in Australia.) So why did Streeton turn to an official exhibition in France? What does that decision mean about Australian Impressionism upon its translation abroad? What does it mean about the reception of Australian Impressionism, or any Impressionism for that matter, in places such as England and France?

If Australia’s Impressionists may be taken as any indication of the type of future questions asked by art historians and future exhibitions held at the National Gallery, it would follow that they will explore the multiplicities and complexities of identity: artistic, national, transnational. More than pretty pictures of the Australian landscape, Australia’s Impressionists exemplifies the epistemological and institutional shifts reverberating throughout the discipline of art history. Still, this does not constitute an entirely new direction either for the field of nineteenth-century art and visual culture or the subfield of Impressionist studies. In 1990 Norma Broude and her co-authors published World Impressionism, stating that: “All over the world in the nineteenth century there was an impulse to paint contemporary life and experience directly from nature, to study the effects of nature’s light, and to use a lighter palette and looser brushwork to proclaim the artist’s individuality and sincerity and the immediacy of the experiences that the canvas mediated for the viewer.”[6] In her chapter in that weighty tome, Virginia Spate raised issues around art and identity that were so central to Australia’s Impressionists.[7] Impressionists Conder, Roberts, and Streeton, she wrote, painted “truth to the perception of a fleeting moment, reliance on the immediacy of personal sensation, and distrust of convention and memory” and thus “symbolized the desires clustering around the notion of Australia as a new land, a land of abundance, health, and happiness.”[8] What will strike those who are well schooled in Australian Impressionism is the consistency of this discourse throughout the past three decades.

To be sure, the world of Impressionism extends outside of France. How we work to write a world history that balances and attends to the local, the national, and the international (and the colonial and the neocolonial) will be critical to future research, publications, and exhibitions. It is the achievement of Australia’s Impressionists to have raised these questions. It will be for the rest of the field to answer them.

Alexis Clark

Postdoctoral Fellow at Washington University in St. Louis

a.m.clark[at]email.wustl.edu

[1] Gerard Vaughan, in his catalogue essay for the 2007 Australian Impressionism exhibition, raised this issue of what to call these artists: “The art of the painters we are including in our exhibition [many of the same artists seen in the National Gallery’s Australia’s Impressionists]—under the title of Australian Impressionism—is clearly very different to the style of the mainstream Impressionists, and the freshest, lightest and brightest studies by Roberts, Streeton, Conder, McCubbin and Sutherland remain far removed from Monet’s or Renoir’s chromatic innovations. . . . Why, then, has it become accepted to describe the new plein-airism developed by the artists working in and around Melbourne and Sydney in the 1880s and 1890s as ‘Australian Impressionism’? As already suggested, the term was ‘in the air’, and it referred to a new, radical spirit in contemporary painting. The idea, therefore, came to be readily associated with the new international style of plein-airism which developed in the 1870s and 1880s.” See Gerard Vaughan, “Some Reflections on Defining Australian Impressionism” in Australian Impressionism, exh. cat. (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2007), 16.

[2] Christopher Riopelle, Australia’s Impressionists, 14: “An evolving sense of national identity was a global phenomenon in the later decades of the nineteenth century. In Australia it anticipated by decades the political union that came with Federation. Each nation looks different from its neighbours; it has its typical and distinctive landscape features; landscape imposes a way of life, as an Australian jackaroo or North Sea fisherman can attest. Each nation can recognise itself in landscape and so in the nineteenth century its representation on canvas became a privileged forum for collective self-reflection. This proved particularly so in places as yet without a strong visual tradition based on the European model. Here was where that tradition would be forged. Thus, what came to be called national landscape painting emerged as a highly varied international movement and an engine for the spread of Modernism.”

[3] The lids were supplied by a friend in the tobacco trade.

[4] More than a decade has passed since Tate Britain held the 2005 exhibition Turner Whistler Monet (and since Tate Liverpool held the exhibition Turner Monet Twombly). The National Gallery’s Australia’s Impressionists may be seen, I think, as a sort of postscript to the story told at Tate Britain. One wishes that the curators in 2005 had thought to extend their exhibition’s scope to include Roberts and so demonstrate the correspondence between his work on the banks of the Thames and that of Turner, Whistler, and Monet, a correspondence traced in Australia’s Impressionists by text alone and not by works of art.

[5] Andrew Brown-May has detailed this expansion in an essay published as part of the 2007 Australian Impressionism exhibition. See “The City Toil: Impressionist Views of Marvelous Melbourne,” in Australian Impressionism, exh. cat. (Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2007). Brown-May summarizes Melbourne’s boom: “In the 1880s the city . . . experienced a boom in land, fortune and people. The population leapt from 268,000 in 1881 to 473,000 in 1891, the fastest rate of growth since the 1850s, much of it coming from migration rather than natural increase. The latter years of the notorious land boom of the 1880s, a period of unbridled speculation when new building activity was double the national rate, were followed by the spectacular crash of the early 1890s, when defaulted loans sent ripples through the financial sector that reverberated for a generation.”

[6] Norma Broude, ed., World Impressionism: The International Movement, 1860–1920 (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990), 10.

[7] Ibid., 117. “Australia, which had no independent status as a nation, being composed of six British colonies, had just celebrated the first centenary of white settlement. As the centenary approached there had been considerable discussion as to whether there was—or ever could be—an Australian school of painting. Because most artists had been recent immigrants and there were no entrenched art institutions or academy, there was no unified tradition of Australian painting. There could, then, scarcely be an avant-garde, and there was no history of deliberate provocation of the bourgeoisie.” One year before Spate’s chapter was published, Leigh Astbury also raised these points. See Sunlight and Shadow: Australian Impressionist Painters, 1880–1900 (Sydney: Bay Books, 1989), 6–22.

[8] Ibid.