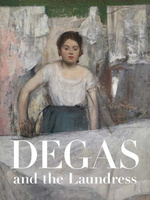

Degas and the Laundress: Women, Work, and Impressionism

Reviewed by Ruth E. Iskin and Andrea Wolk RagerRuth E. Iskin

Associate Professor Emerita of Art History

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

Email the author: ruth.e.iskin[at]gmail.com

Andrea Wolk Rager

Associate Professor, Department of Art History and Art

Case Western Reserve University

Email the author: andrea.rager[at]case.edu

Citation: Ruth E. Iskin and Andrea Wolk Rager, exhibition review of Degas and the Laundress: Women, Work, and Impressionism, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 1 (Spring 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.1.18.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Degas and the Laundress: Women, Work, and Impressionism

Cleveland Museum of Art

October 8, 2023–January 14, 2024

Britany Salsbury, ed.,

Degas and the Laundress: Women, Work, and Impressionism.

London: Yale University Press and Cleveland Museum of Art, 2023.

256 pp.; 257 color and b&w illus.; chronology; appendices; selected bibliography; index; list of lenders.

$65 (hardcover)

ISBN: 9780300273229

NB: In this review, Andrea Wolk Rager addresses the exhibition, and Ruth E. Iskin discusses the accompanying catalogue.

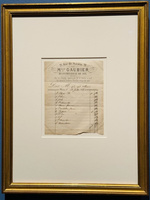

One of the most captivating objects on display in the recent exhibition Degas and the Laundress: Women, Work, and Impressionism was a small, creased, and slightly discolored rectangle of paper, surrounded by a simple gold frame, placed near the threshold between the first and second rooms (fig. 1). This printed sheet of paper was a working document, a personalized lithographic template completed in ink with a careful script, its lower edge unevenly torn and a tiny stray dot of ink near its center. The paper had, at some point, been folded, perhaps to be placed in an envelope or a pocket. Across the top are the words “Melle. Gaubier” and “blanchisseuse de fin” (laundress of fine cloths) surrounded by several flourishing curls and with the address “21, Rue de Navarin, 21.” Dated to July 18, 1868, the document is a receipt of assorted clothing cleaned at Mlle Gaubier’s boutique de blanchissage and their respective prices, including three men’s shirts, a woman’s shirt, two petticoats, and six handkerchiefs, among other items. Placed on the wall of the exhibition alongside this humble, quotidian document were two works by Edgar Degas (1834–1917) depicting the figure of the laundress: the oil on canvas painting La Repasseuse (Woman Ironing; fig. 2) and the oil on paper study La Blanchisseuse (The Laundress; Davis Museum at Wellesley College, Wellesley). Both are dated to around 1869, the year after the receipt was issued by Mlle Gaubier, when Degas turned to the subject of the laundress as part of his exploration of modern life in the city of Paris. Although Mlle Gaubier’s establishment was near Degas’s studio, the artist sought out his favorite model to play at the role of laundress. It was Emma Dobigny (1851–1925) who posed for Degas, as attested by surviving correspondence, performing the repetitive movements of a repasseuse, who specialized in skilled ironing. In the painting and study, Dobigny’s body is turned towards the viewer, a fleeting expression vacillating between boredom and bemusement on her face. An iron gripped firmly in her right hand, Dobigny’s arms are blurred by shifting outlines. This lack of clarity suggests perhaps artistic indecision or, more compellingly, evokes the rapid and restless movement of the repasseuse as she smooths and straightens the wrinkled fabrics held down by her left hand. Degas’s evocative depictions of the labor of the laundress are arresting in composition and facture, bold explorations of an ephemeral moment rendered in thin veils of scraped paint and shivering brushstrokes. However, as a visitor to the exhibition, I found myself turning again and again from the paintings back to Mlle Gaubier’s receipt. The object label explained that, apart from the testimony of this receipt, no records have been found of Mlle Gaubier. It thus stands as an index, a rare trace of contact with one of the thousands of women employed in the burgeoning laundry industry in Paris in the nineteenth century, bearing witness to her professionalism, her labor, and her struggle to support a business through the accounting of each sou. It also lays bare the gap between the laundress as a construct, a figure of modernity perceived through the lens of gender and class privilege by Degas and his contemporaries, and the lived experience of these individuals, their biographies and voices largely lost.

Expertly curated by Britany Salsbury, curator of prints and drawings at the Cleveland Museum of Art, and on view until mid-January of 2024, Degas and the Laundress was the first exhibition dedicated to this subject. Tightly focused, compellingly organized, and thoughtfully researched, the exhibition was comprised of nearly a hundred works by numerous artists, over a dozen by Degas alone, drawn from a range of media, including oil paintings, pastels, drawings, prints, photographs, and carefully selected ephemera. The exhibition was organized into six thematic groupings across four large rooms: “Degas and the Laundress,” “Laundresses and the City,” “Representing Labor,” “Laundry and the Modern Landscape,” “Laundresses as Individuals,” and “Degas’s Final Years.” These sections are closely echoed in the organization of the plates in the accompanying catalogue, although with some differences. For example, while the catalogue groups all of the works by Degas into a single set of plates, only about half of these appeared together in the first room (fig. 3). The remainder were strategically interspersed across the succeeding sections, punctuating the rooms at intervals to create an ongoing dialogue between Degas and the wider visual culture of the laundress in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century France. Throughout the exhibition, restrained design cues further immersed the viewer in the world of the laundress, signaled at the outset with the paneling surrounding the opening title that subtly evoked a Parisian shopfront (fig. 4). Appropriately, the walls were painted in a palette of hues best described as variations on French blue, reminiscent of the aprons often worn by laundresses, as well as the flowing waters of the Seine on a bright day.

With its breadth of media and artists, the exhibition not only examined this overlooked category of artistic production within Degas’s oeuvre, but also elucidated the emergence of the figure of the laundress across French art and popular culture at the time. Consequently, the laundress manifests as a distinctive but illusory figure of modernity, raising fraught issues around gender, labor, industrialization, and the city. Indeed, the longer one lingered in the spaces of the exhibition, the more one became aware of tracking the distinctive silhouette of the laundress at her labors. Out of the corner of the eye, a visitor could spot another unmistakable female form, hips shifted at an angle, head tilted to the side as her body contorted to offset the weight of cumbersome laundry baskets laden with fabrics, as seen in Pierre Bonnard’s (1867–1947) lithograph The Little Laundress (fig. 5). The laundress could be found traversing liminal urban spaces in her unofficial uniform of a loose blouse that could be rolled up to the elbows, an apron often seen over her skirt, her hair piled on her head in a simple bun or tucked under a bonnet. Often, she could be glimpsed ascending or descending the riverside stairs that led to and from the bateaux-lavoirs (washing boats), as in Honoré Daumier’s (1808–79) The Laundress (fig. 6), where the figure is accompanied by her young child. In the guise of a Parisian flâneur, the viewer could also spy the laundress at work within the cramped space of a laundry boutique. As depicted in Degas’s Repasseuse à contre-jour (Woman Ironing; fig. 7), the exhibition visitor came to recognize the particular hunch of the laundress’s shoulders as she passes a heavy iron carefully back and forth over a never-ending pile of delicate textiles, hemmed in by a coal stove to one side and hanging rows of damp fabrics to the other.

While nineteenth-century French historian Jules Michelet (1798–1874) decried the rise of female workers outside the home in “this age of iron,” the testimony of this exhibition suggests that perhaps he should have termed it “the age of ironing” (52). The increase in demand for laundresses to clean the proliferating garments, bedclothes, and draperies of a growing urban population, made possible in part by the rise in industrial production and global commerce, met with a desperate need of ready employment for thousands of women. Such labor was not only poorly regulated and financially exploitative; it was also physically demanding and hazardous to the health of women who often had no other viable source of income apart from sex work, to which they were frequently forced to turn in any case. At once highly visible presences in the spaces of the city and invisible in their relative individual anonymity, the laundress quickly became a new urban type uniquely situated between the modern preoccupations with dirtiness and cleanliness, contamination and purity, corruption and morality. For example, in the thematic section “Laundresses in the City,” two small, printed paper dolls were displayed in one of the cases at the center of the room. The chromolithographs by an unknown artist depicted the figures of a blanchisseuse (Laundress, ca. 1880–1900; The Cleveland Museum of Art, Ingalls Library, Cleveland) and a repasseuse (Woman Ironing, ca. 1880–1900; The Cleveland Museum of Art, Ingalls Library, Cleveland), indicating their ubiquity within the modern cityscape, as well as their ready exploitation and commercialization. Shifting from child’s play to adult fantasies of sexual desire, several stereographs by Pierre Eléonor Lamy (1828–1900) displayed nearby exposed the corporeal vulnerability of the laundress still further. Here, a model posed as a laundress leans forward, her blouse slipping from her shoulders to reveal her breasts to the delectation of the viewer (Studies of Nude and Seminude Women, 1861; Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Département des Estampes et de la Photographie, Paris). The prurient appeal of the figure of the laundress was further bolstered by the popularity of Émile Zola’s (1840-1902) L’Assommoir (1876). This naturalist novel follows the doomed life of a laundress named Gervaise Macquart as she seeks to overcome poverty, abuse, and alcoholism to run her own shop, ultimately ending in tragedy. Part of Zola’s study of what he termed the bête humaine (the beast within), L’Assommoir was represented in the exhibition by illustrations for the book as well as posters and promotional photographs from the theatrical adaptation. Notably, the story was commonly reduced to its more salacious episodes, especially a fight involving buckets of water flung between Gervaise and another woman in a washhouse.

In gathering these varied representations of the laundress and her labors together, the exhibition illuminates Degas’s particular approach to the subject with new clarity. For example, returning to Woman Ironing (see fig. 7), the prurient appeal of the laundress-as-coquette has been replaced with a figure of intense, quiet concentration. It is the work of the laundress that serves as the locus of Degas’s studies, as her precise and rhythmic movements transform the disorder of a rumpled mass of white fabric into a folded, orderly, almost avian, man’s shirt, the stiff and starched uniform of the bourgeois. Above her, textiles in hues of pink, mustard, and pale blue hang from the ceiling, dissolving into painterly streaks of pigment. The mottled white of curtains drawn over the windows and a tablecloth lining her worktable blur the distinction between the fabrics of the laundress’s labor and the oil paints and canvas that comprise the artist’s materials. Degas’s interest seemingly arises from a partial self-recognition, the laundress as artist and the artist as laundress. His attentive analysis of the form and movements of the repasseuse were demonstrated by the two studies displayed alongside these paintings, one gridded for transfer, which record the precise movement of her arms, the incline of her head, and the bend of her back (Study for Woman Ironing [Repasseuse à contre-jour], ca. 1873; private collection, courtesy of Arnoldi-Livie, Munich; and Study for Woman Ironing [Repasseuse à contre-jour], ca. 1873; private collection). Moreover, Degas’s interest in physiognomy, often embedded with racial, class, and gender bias, is evident here as well, reinforced by the inclusion in the exhibition of plates from Eadweard Muybridge’s (1830–1904) Animal Locomotion (ca. 1884–87). As a groundbreaking photographer of human and animal bodies in motion, Muybridge captured the habitual movements of a laundress performing her labors in the nude. Indicative of the nineteenth-century fascination with taxonomies and surveillance, the photographs expose Degas’s own efforts to scrutinize the working-class female body. One of the provocative open questions of the exhibition is whether Degas’s treatment of the figure of the laundress ultimately denigrates or celebrates those labors. Do his representations acknowledge a fellow practitioner of an arduous craft, or do they treat working-class women as a specimen of modern life to be studied and classified?

Escaping the claustrophobic confines of the crowded streets and cramped laundry shops of Paris, the exhibition shifted in its second half to include landscapes on the outskirts of the city. With the transformation of Paris under Haussmannization, many laundry boats and washhouses were displaced to the banlieue, the marginal spaces on the outskirts of the city marked by industrialization and straddling the uncomfortable border between urban and rural. While Degas never ventured into these landscapes for his depictions of the laundress, several of his fellow impressionists did, including Berthe Morisot (1841–95) and Camille Pissarro (1830–1903). Morisot’s painting Paysane étendant du linge (Peasant Girl Hanging Clothes to Dry; Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen) created in 1881, was of particular note within the space of the exhibition. Hanging fabrics to dry on a line in the open air, Morisot’s laundress stands tall, seemingly allowed more room to breathe than her counterparts at the ironing table. Surrounded by a wall of unruly vegetation and with the suggestion of further drying lines behind her, this laundress works in an enclosed environment, in keeping with gendered conventions for representing women. Much like Degas, Morisot seemingly takes advantage of the aesthetic opportunity afforded by the subject to study a female figure at work among loose fabrics hanging in dappled sunlight. Perhaps the most arresting and revelatory work in this section of the exhibition was Gustave Caillebotte’s (1848–94) large painting, Linge séchant au bord de la Seine (Laundry Drying on the Banks of the Seine, ca. 1888–92; Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud, Cologne). Caillebotte, despite being so often associated with the impressionist figure, eschewed depicting a human presence in his contribution to the genre. Instead, he selected a view of myriad white shirts drying on a clothesline strung along the banks of the Seine, with laundry boats to the left and a dirt road flanked by a row of trees receding into the far distance at right. The entire canvas is covered in quick, feathery brushstrokes that suggest a brisk spring breeze whipping down the line of shirts, their very material forming and unforming in a tangle of crisscrossing dashes of paint. Fascinatingly, as related by Salsbury, during preparation for the exhibition, a layer of tree pollen was discovered embedded in the paint layer. This revelation not only verifies that Caillebotte worked en plein air but also emphasizes the environmental interconnectivity of the site, the mingling of particles of organic matter and industrial soot with paint and garments, artist and laundress, alike.

In the last room of the exhibition, a section was devoted to “Laundresses as Individuals.” Gathered here were a selection of works depicting laundresses with known identities. These included Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s (1841–1919) depictions of his common-law wife Aline Charigot (1859–1915), who worked as a laundress and model (fig. 8); Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s (1864–1901) painting of laundress and model Carmen Gaudin (n.d.) from 1888; and Maximilien Luce’s (1858–1941) startling portrayal from around 1905 of laundress and political activist Philiberte Givort (n.d.), whose unforgiving expression and muscled arms suggest simmering discontent and an untapped source of power. Luce’s portrait of Givort alludes to a larger history of labor unrest and unionization that grew during this period, as laundry workers agitated for better pay and working conditions, a history addressed in part by a chronology in the catalogue. However, much like Mlle Gaubier’s receipt in the first room of the exhibition, this last section was disrupted by the unexpected and powerful testimony of a massed grouping of nine photographic postcards portraying laundry workers posed outside of their respective blanchisseries (fig. 9). Dating to around 1900–10, these popular and inexpensive records of daily life in Paris are deeply poignant in the anecdotal details they capture. Some feature shop pets, such as the two dogs that appear in one and the cat held in the arms of a worker in another. Others include young children, possibly brought to work by a parent, including a small girl with her smaller doll and a baby balanced on a woman’s hip. Once again, the biographies of the individuals captured on these small postcards remain unknown, but after tracing the figure of the laundress as a construct throughout the exhibition, the postcards provided a riveting window onto the real laundry workers who lived and labored in the hopes of building a better life.

The catalogue for this exhibition is the first volume devoted to Degas’s art representations of laundresses, a subject the artist treated in about forty works in different media and revisited over half a century. Despite the growing corpus of studies of Degas’s art in recent years, the subject of the laundress has been largely ignored since Eunice Lipton’s pioneering studies published some four decades ago, which Salsbury acknowledges as an inspiration.[1] The catalogue features eight essays written by art historians, a historian, and a literary scholar; these are followed by sections that present numerous images by contemporaries of Degas, divided into several topics and accompanied by Salsbury’s brief introductory texts. It concludes with three valuable appendices followed by a selected bibliography, index, and list of lenders.

Salsbury’s introductory essay, “Degas and the Laundress,” provides an overview of Degas’s numerous paintings, drawings, and prints of laundresses, discussing many in detail, from the earliest to the latest, and analyzes changes in the artist’s approach over time. Her discussion of iconography, Degas’s artistic processes, and the ways in which the subject of the laundress figures within the artist’s biography stresses that Degas was attracted to the subject because it represented modern life. Her essay sets his artworks within several contexts, including the laundresses’ lives and the difficulty of their working conditions and labor, which was physically arduous, repetitive, and monotonous. Salsbury credits Degas with making working-class women’s labor visible in his depiction of contemporary Parisian life, but suggests that his complex relationship to female laborers combines both empathy and disdain. She sees his works on the laundress as part of the artist’s broader interest in depicting working-class women at work, as in his numerous representations of ballerinas and in many monotypes of Parisian sex workers in brothels, where they both lived and worked. To these, we might add Degas’s numerous representations of millinery workers shaping or decorating fashionable hats and the occasional saleswoman in a millinery boutique. Salsbury also includes visual representations of laundresses in some photographs and in numerous artworks by artists who preceded Degas, by his contemporaries, and by artists that followed him. This rich and expansive study deepens our understanding of the subject both within Degas’s oeuvre and within the context of the social conditions of laundresses and their representation in Parisian art and culture.

Most of the subsequent essays focus on a particular aspect or specific context for Degas’s depictions of laundresses. Michelle Foa’s “Degas on French Textiles, the Transatlantic Cotton Trade, and the Work of Ironing” extends her deep interest in the subject of materiality in Degas’s oeuvre to the artist’s representation of laundresses.[2] She analyzes Degas’s laundresses ironing within the broader context of Degas’s fascination with materials and textiles and proposes that, for Degas, a close connection existed between French fabrics, Southern cotton, the Parisian laundress, and New Orleans cotton merchants. She highlights Degas’s personal interest in fabrics, noting that he depicted numerous and differing fabrics, including the raw cotton and ballerinas’ gauze outfits, and that he himself collected carpets, bonnets, and handkerchiefs, some of which he displayed in his living quarters. Foa’s reading departs from the interpretations that highlight Degas’s representation of dreary strenuous labor, arguing instead that Degas’s ironing women manifest their “dexterous working” with “trims, ruffles, pleats, cuffs, and collars with the iron” (32).[3] She concludes with the suggestion that Degas’s works representing laundresses show the artist’s identification with the figures featured in these works, and notes that several links existed between Degas and the laundresses: in addition to the link between the laundresses’ close engagements with fabrics and Degas’s own love of textiles, the laundresses’ dirty work environments paralleled Degas’s notoriously unclean studio; and the movement of the laundresses’ hands at work echoed the artist’s art-making gestures. Foa’s focus on the fabrics in Degas’s images of laundresses, “hanging or lying flat, spread out or folded, wrinkled or smooth, limp or crisp” (30), adds an important angle to the catalogue and to the study of these artworks and their relationship to the artist’s oeuvre more generally.

Richard Thomson’s “The Skillful, the Social, and the Scurrilous: The Imagery of the Laundress in Naturalist Painting” focuses on an important artistic context for Degas’s work on the laundresses, namely naturalist representations of the subject during the artist’s lifetime. Thomson, who assembled a fascinating group of naturalist paintings and press illustrations, proposes that the popularity of the subject of the laundress had to do with the Third Republic’s promotion of egalitarianism, as well as with the morally evocative associations of dirtiness and cleanliness. Focusing his discussion mostly on the former, he notes that “the laundress had come to emblematize the working-class woman’s identity in the republic” (37). Among the naturalist paintings Thomson discusses is one by a woman artist, Marie Petiet’s (1854–93) The Laundresses (1882; Musée Petiet, Limoux). It represents life-size figures, one of a mature woman ironing, seen from the back, and six young women whom she is training in the skills of ironing. Thomson’s statement that this painting offers “the eye of exactitude of someone who had done such work” (52) is intriguing and invites further thinking about gender in relation to representations of laundresses.

Charles Sowerwine, in “Putting People in Their Place: Class and Gender in Degas’s Paris,” discusses the meaning of being a bourgeois man in Paris during the nineteenth century, including Degas’s own status as an haut-bourgeois man, as well as the topics of working-class women and bourgeois women’s domesticity. Readers would have benefited from a mention of some of the dynamic changes that were taking place in women’s roles and aspirations during Degas’s time, a period in which French women demanded, as Karen Offen has noted, “equal rights, liberty, a choice of social roles and responsibilities, educational opportunities . . . the right to work and equal pay for equal work,” and “a single standard of morality for both sexes.”[4] The historical complexity of the time could have been conveyed, for example, by mentioning not only women’s lack of education but also the 1880 Camille Sée law that established state-sponsored secondary education for young women, leading to significant changes by the mid-1890s, including the first female doctors and lawyers.[5] The essay includes discussion of some of Degas’s works, and at its conclusion quotes a critic’s assertion that Degas was “a feminist” (55).[6] At the very end of his essay the author states that in some ways Degas “transcended the limits of his class and gender” (55) but does not elaborate on this intriguing statement.

Gretchen Schultz, in “Working-Class Women, Alcohol, and Degas’s Women Ironing,” presents a wide array of commentary from Degas’s time about working women and alcohol, ranging from dismissive contempt to moralistic condemnation and patronizing sympathy. The essay discusses discourses of various groups, such as public health concerns expressed by hygienists, a medicalization of alcohol that associated alcoholism with workers, and the discourse of the Temperance Movement, which focused on the negative consequences of male workers’ alcoholism on their families. Some hygienists claimed that the profession of the laundress was a significant cause of alcoholism among women. Schultz’s essay demonstrates the extent to which widespread beliefs about working women and alcohol expressed ideologies of the time. The context she presents sheds new light on Degas’s representation of the laundress with a wine bottle in her hand, but even more so, on the comments about this work. By analyzing this work within an extensive textual and social context, Schultz argues that the wide-ranging interpretations of Degas’s work on the subject during his lifetime reflect the array of beliefs that prevailed at the time about working-class women and alcohol.

Aleksandra Bursac, in “Idyll to Industry: Infrastructures of Cleanliness in Nineteenth-century France,” illuminates another aspect of thinking about Degas’s representation of laundresses by exploring the laundry industry, its workers, and their conditions in France. She discusses the shifts in laundry practices with the introduction of new machinery, new types of soaps and bleaches, and a range of smaller irons suited to contemporary fashions and fabrics. She draws distinctions between different workers within the laundry industry, noting that women ironers were at the top of the hierarchy since their work required skill and expertise. Like Foa, Bursac argues that Degas was more interested in the woman ironer’s skillful gestures than in “crude mechanical action” (78) and draws attention to parallels between Degas’s own working methods and those of ironers, both of which involved repetitive gestures.

Claire White, in “The Stench of the People: On the Mania for Emile Zola’s L’Assommoir,” discusses Zola’s best-selling novel. The essay discusses the novel’s wide influence at the time, manifested in a popular theatrical adaptation and innumerable references to it in performances, caricatures, products, postcards, posters, and other forms of popular media. White also briefly discusses Degas’s and Zola’s comments on each other’s representation of the subject.

It is perhaps unusual that most of the essays in this exhibition catalogue focus on the various contexts for Degas’s works representing laundresses, more so than on Degas’s works themselves. The essays include valuable information and analysis of several such contexts, and in this sense, the catalogue adds a dimension that could not be conveyed in the exhibition itself. Following the essays, the catalogue presents several sections of plates representing laundresses, divided into topics: Degas’s representations, the laundress in the context of the city, the representation of labor, laundry and the modern landscape, laundresses as individuals, and appearances of laundry and laundresses in nineteenth-century ephemera. Brief informative introductions by Salsbury accompany her selection of a wide variety of visual images on laundry and laundresses made in a range of media. These sections provide a stimulating expanded scope to the representation and circulation of the laundress’s image during Degas’s time. Finally, the catalogue presents three highly valuable appendices: the first, “Catalogue Raisonné of Degas’s Laundress Works,” is authored by Salsbury, while the next two are co-authored by Salsbury with Jillian Kruse: “Chronology: Degas’s Life and the Parisian Laundry Industry, 1785–1919,” and “Writings from Degas’s Time about his Laundress Works.” All three appendices enhance the value of the catalogue as an indispensable resource for future studies on the subject. The volume constitutes a welcome addition to Degas studies, especially to his works on laundresses.

Notes

[1] Eunice Lipton, Looking into Degas: Uneasy Images of Women and Modern Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 118–50; Lipton, “The Laundress in Late Nineteenth-Century French Culture: Imagery, Ideology and Edgar Degas,” Art History 3, no. 3 (September 1980): 295–313.

[2] Michelle Foa, “In Transit: Edgar Degas and the Matter of Cotton, between New World and Old,” Art Bulletin 102, no. 3 (September 2020): 54–76, 10.1080/00043079.2020.1711487; Foa, “The Making of Degas: Duranty, Technology, and the Meaning of Materials in Later Nineteenth-Century Paris,” Nonsite.org, accessed February 12, 2024, https://nonsite.org/author/mfoa/.

[3] Foa credits Lipton’s mentioning of Degas’s likely appreciation of the ironer’s skill, referring to Lipton’s article in Art History (see note 1).

[4] Karen Offen, Debating the Woman Question in the French Third Republic, 1870–1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2028), 1.

[5] Deborah L. Silverman, “Amazone, Femme Nouvelle, and the Threat to the Bourgeois Family,” in Silverman, Art Nouveau in Fin-de-Siècle France: Politics, Psychology and Style (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 66.

[6] The brief mention of a critic’s claim that Degas was a feminist would have benefited from Martha Ward’s analysis; see Ward, “The Eighth Exhibition, 1886: The Rhetoric of Independence and Innovation,” in The New Painting: Impressionism 1874-1886, exh. cat., ed. Charles S. Moffett. (San Francisco: The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1986), 433.