The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

Henri Rousseau: Jungles in Paris Henri Rousseau: Jungles in Paris The exhibition was also shown at: |

|||||

| To enter the Henri Rousseau exhibition at the National Gallery in Washington this past fall was to walk, in a sense, into a jungle. The door to the show was cut into an enormous floor-to-ceiling reproduction of Rousseau's The Dream, sending visitors into a tangle of overgrown leaves and foliage. This was a clever device: to force a visitor to step physically into a painting, and into a jungle, not only immediately cued a transformation of environment, but foreshadowed the themes to come: of dislocation and otherness, of inside and outside, of vision and body—themes, in other words, that are crucial to understanding Rousseau. | ||||||

| Henri Rousseau: Jungles in Paris was a visually exciting, important exhibition. A collaboration between the Tate Modern, the Musée d'Orsay and the Réunion des musées nationaux, in association with the National Gallery of Art, this was the first Rousseau retrospective in the United States since MoMA's show in 1985, which had a quite different agenda. That exhibition and its catalogue focused primarily on Rousseau's influence on vanguard artists of the twentieth century: he was the rebel, the outsider who represented purity and instinct. Now that Rousseau's place in the modernist pantheon has been secured, it seems, we can cast our nets more widely to consider other issues—of audience, politics, and history. In this most recent exhibition, selected by Christopher Green and Frances Morris with Claire Frèches-Thory, there were certainly references to Rousseau's modernism and to his outsider status—labels told us that certain works "caught the attention of the avant-garde"—yet the focus was not so much biography or canonization, but contextualization. What was being contextualized, specifically, was the artist's jungle paintings—the densely packed, enigmatic fantasies painted mostly between the years of 1904 and 1910. The jungle pictures were understood here not merely as one artist's quirky fixation, but as part of a broader cultural phenomenon, namely the French fascination with exoticism during the nation's colonial expansion. | ||||||

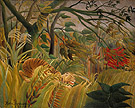

| The first room contained a single painting, the fantastic Tiger in a Tropical Storm (Surprised!) (fig. 1). Painted in 1891, this was Rousseau's first jungle picture, and it shows a tiger recoiling in terror as the wind whips through the trees and lightning cracks the sky. After its exhibition at the 1891 Salon des Indépendents, the artist took a famously long hiatus from the theme, not returning to it until 1904. And accordingly, we do not see another jungle picture after this one until much later in the exhibition; this first painting was here, as in Rousseau's career, a hint of what was to come. Perhaps more important, however, was the psychological effect of this pared-down presentation. Hanging alone in the dimly-lit room, the painting seemed to glow with tension. Here was a ferocious creature with sharp white teeth, but sympathetic also; the lighting fell on wild eyes that looked, terrified, into the space beyond the picture, as if to mirror the viewer's own reaction to this ominous setting. This was an exhibition, it seems, in which psychological effect was key in the curatorial message and thus carefully manipulated. It presented the French fascination with the exotic with a certain scholarly distance, yet still allowed for us as viewers to engage in the thrilling terror of the unknown. | ||||||

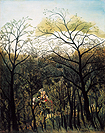

| Jungles in Paris was not just about jungles. With the exception of Tiger in a Tropical Storm, the entire first floor was devoted to works in other genres—portraits, landscapes, scenes of daily life, and political allegories. A section devoted to the artist's early forest scenes introduced a theme that recurs throughout Rousseau's oeuvre, especially in the jungle pictures: unexpected, nonsensical juxtapositions. In Promenade in the Forest, for example, a wooded scene is made strange by the presence of a well-dressed woman (fig. 2). With fallen branches, the path is a bit wild for a mid-day stroll, and her startled, slightly twisted posture conveys a sense of dread: she is out of her element. In Carnival Evening of 1886, Rousseau plays even more with the feeling of the unexpected by inserting two carnival figures in a moonlit forest landscape (fig. 3). The painting has a stage-like quality, and the wooded backdrop looks like a set curtain that has dropped behind them, heightening the sense of incongruity. Rendezvous in the Forest likewise presents an unexpected glimpse of two lovers in eighteenth-century costume, through an opening in a thicket of trees. Here the woods become a place of secrecy, and of desire, as they are in the later jungle paintings (fig. 4). While providing a sense of Rousseau's range, these first rooms also introduced important biographical information and insight into his working methods. In particular they emphasized how his subject matter is drawn from a startling variety of popular sources—illustrated magazines, postcards, and photos. | ||||||

| Rousseau's work is full of the kinds of contradictions, deliberate or not, that we see in these early forest paintings. Indeed the show tended to foreground the notion of contradiction as a framework for understanding Rousseau and his quirky output: he was the outsider artist who wanted official acceptance, the painter of foreign lands who never left Paris, the hero of the moderns who handled paint like an academician. Even the title, Jungles in Paris, is a contradiction, one with several possible layers of meaning. It might refer to the yearly display of Rousseau's jungle pictures at the Paris Salon des Indépendents, or perhaps to the man-made jungles he visited in the city's Jardin des Plantes, a literal "jungle in Paris." More generally, with its semantic nod to improbability, the title conjures up the irony built into Rousseau's own working situation: the jungle paintings were the concoctions of a city-dweller. Like the woman in Promenade in the Forest, Rousseau was out of his element when he painted the jungle, and the exhibition gently emphasizes this irony so that we might use it to approach his paintings, to understand their strange ruptures, their dissonances, their awkwardness, and their failure—or refusal—to signify in a traditional way. | ||||||

|

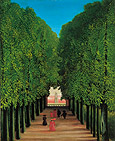

One of the most illuminating of the first-floor rooms contained the artist's renderings of scenes in and around Paris. The pictures are remarkably, relentlessly un-exotic: there are scenes of Parisians strolling through the Jardin du Luxembourg, of families picnicking in vaguely industrialized yet appealing suburban landscapes, and of a laborer working in an orchard. There are no unexpected juxtapositions, nothing familiar made strange; rather, each scene is comfortingly predictable. What is so striking about these pictures is not just their conformist bourgeois subjects, but the way in which the subjects exist in their space, and especially the way in which nature is rendered. In a painting like Avenue in the Park at Saint-Cloud (1908), for example, nature is not the wild tangle of foliage that we've come to associate with Rousseau; rather, it is hyper-organized, symmetrical—and most importantly, legible (fig. 5). Trees stand in an orderly line along the path, like soldiers, pointing the way to a trite glimpse of an architectural vista. Shadows fall in a grid-like pattern, further emphasizing the underlying perspectival structure. Such pictures remind us that Rousseau understood the relationship between vision and power: in these suburban scenes bourgeois comfort is conveyed in terms of visual mastery over an organized natural world. However, neither the wall text nor the essays in the catalogue made much of what seems to be a crucial difference in the artist's treatment of nature, in his ability to make it convey either psychological comfort or terror. | |||||

| In elaborating Rousseau's relationship with the exotic, this room devoted to the mundane was crucial. In their quiet orderliness, the suburban pictures set up a striking counterpoint for the larger, wilder imaginings of terrifying faraway jungles. It was somewhat disappointing, then, to discover that the next section of the exhibition was not the jungle pictures but rather the artist's political allegories. To be sure, Rousseau's politics may be relevant for understanding the ideologies coursing through the jungle pictures: he was a nationalist and ardent supporter of the Third Republic. In works like Representatives of Foreign Powers Coming to Greet the Public as a Sign of Peace, France is presented as a benevolent global power bringing peace and civilization to the world (fig 6). And there were plenty of important pictures in this section, including the mesmerizing War, which Rousseau painted in 1894 as a general condemnation of violence (fig. 7). Packed with brutal details—limbs are amputated, a bird pecks away at a human corpse, a face with a bullet wound peeks out between the legs of a neighboring corpse—the painting spreads out its violence while swiftly condensing it in a single figure, the personification of war, who is all hair, teeth, and jagged whiteness. Never has a picture about motion and chaos been executed in so controlled and static a manner. The violent images occur in isolated zones which are layered, collage-like, one on top of the other. The tension between subject matter and style is palpable here: frozen, rigid forms are at odds with the pathos of the subject, and the picture never quite makes sense. Perhaps this is its power. Still, while it was certainly a treat to see this and the other political paintings, their presence came as an interruption to the show's overarching themes—the tension between country and city, between foreign and familiar—which the previous rooms had done so well to set up. | ||||||

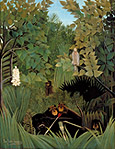

| The promised jungle pictures began upstairs. The first room contained several of what the organizers called Rousseau's "idyllic" jungle scenes, which tend to show animals at rest, peering out from amidst the lush jungle foliage. Typically these creatures look right at the viewer, wearing vaguely stunned expressions that function to underline the chasm between the viewer and the scene represented: their stares communicate that this is their territory, and you are an outsider. This is reinforced by the always-present band of foliage in the foreground that denies the viewer any sense of bodily entry into the picture. The centerpiece of the room was The Merry Jesters, which shows a collection of various jungle animals, including monkeys, presented with inexplicable props: a red back-scratcher and an overturned bottle of milk that hovers, impossibly, in the foreground space (fig. 8). (Indeed, the theme of the room was the artist's use of unexpected props, which explained the hanging of these jungle scenes with works such as the Portrait of a Woman, whose subject rigidly holds a tree branch.) In The Merry Jesters, the back-scratcher and milk bottle are not only unexpected but man-made, and in this way the painting introduces us to yet another theme in Rousseau's work: the disconcerting yet often comical overlap between human and animal. The Merry Jesters was flanked by Two Monkeys in the Jungle, with its human-looking simians, and the Football Game, with its simian-looking humans (figs. 9 and 10). | ||||||

| The climax of the exhibition came in the next room, where, suddenly, everything was on a larger scale—the paintings, the objects, and the gallery itself—and for the first time we were totally surrounded by jungle pictures. All were painted between 1904 and 1910, and, unlike the previous room, all dealt with themes of violence and struggle. The selection included several works showing animal combat, including The Repast of the Lion, and Horse Attacked by a Jaguar (fig. 11). There were also paintings with human combatants, such as Jungle with Setting Sun, in which the human is made even more exotic than the animal; dark and featureless, he is a blank symbol of Otherness (fig. 12). With jungle paintings on each wall, the visitor was thrust into a strange, dreamlike word, where dramas unfold beneath towering flowers and giant blades of grass. The paintings are big, packed with details, and it was thrilling to see so many in one space. | ||||||

| What made this section of the exhibition so effective, however, was the supplementary material presented alongside the paintings: sculptures, taxidermy, popular imagery, and travel literature. One wall was covered from floor to ceiling with the illustrated covers of the periodical Petit Journal, showing images of faraway lands and life in the colonies (fig. 13). Popular images from other sources hung alongside some of the paintings. For example, Jungle with Setting Sun was positioned next to an illustration from the book Bêtes Sauvages, from which the animal in the painting was traced. Cases along the walls contained travel accounts and journals reporting on expeditions, such as the Journal des Voyages. Walls were decorated with foliage patterns that appeared to be illustrations from a natural science book or journal, blown up to a life-size scale. Moving back and forth between these different media, between the paintings and the supplementary material, the feeling was one of context and interaction. | ||||||

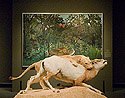

| In the center of the room stood a large taxidermy animal group made in 1886, "Senegal lion devouring an antelope," which Rousseau had studied at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris (fig. 14). On the far wall, in a prime position for comparison, hung the painting that derives directly from it: The Hungry Lion Throws Itself on the Antelope, which Rousseau exhibited at the famed 1905 Salon des Indépendants with Matisse and the fauves (fig. 15). With the animals set in an identical position, Rousseau's painting is almost a literal transcription of the taxidermy; only the wounds, the dripping blood, and wild-eyed gaze of the lion are the artist's inventions, all of which inject a spark of life to his dead models. Indeed, the opportunity to reflect on the "deadness" of Rousseau's source was a kind of revelation. Seeing the taxidermy in front of the painting, not only do we see how important such sources were for his work, but we get a different take on the sense of "stillness" that pervades so many of his paintings: taxidermy specimens are frozen. Flanking the center group were two life-size sculptures by Emmanuel Frémiet: his Gorilla Carrying of a Woman of 1887 and the Bear Cub Hunter, which Rousseau would have seen at the 1889 World's Fair and at the Jardin des Plantes, respectively (fig. 16). | ||||||

| On the one hand, then, the room functioned as a straightforward catalogue of Rousseau's sources. The artist had never gone to Mexico or seen its jungles, as Apollinaire had claimed; his paintings were shaped instead by visits to botanical gardens, to the zoo, and to colonial exhibitions. We learn that often his imagery comes straight out of the Jardin des Plantes, where he worked directly from stuffed animal displays, and that he sometimes derived his compositions from journal illustrations. But on the other hand, and perhaps more importantly, the documentary material reminds us of the ideology out of which Rousseau's mysterious and often angst-ridden jungle pictures emerged. In particular the wall of Petit Journal covers was a powerful document of an era's view of the colonial Other. Scene after scene of menacing natives and impenetrable forests provided a first-hand glimpse into the terror and fascination Parisians felt toward faraway lands (figs. 13 and 17). With foliage on the walls and life-size battling animals, the room mimicked the natural world while remaining totally artificial, which was crucial: its artifice reminded us that what Rousseau had at his disposal was not the real jungle but the imagined jungle as it loomed in the nineteenth and early twentieth-century French consciousness. This room reminded us, in other words, that the exotic is a construct. | ||||||

| Standing before the enormous jungle pictures, one begins to understand how, formally speaking, they articulate the paradoxes of the colonial era for French audiences. It has to do with the way they create a deliberate sense of dislocation by playing with the viewer's visual and bodily experience of the painting. The jungle paintings pack so much information into the visual field: each leaf is turned toward us for maximum legibility, details are aggressively clear, plants seem to line up for inventory. In submitting the exotic to visual organization—in presenting it as something that is knowable—the paintings suggest a kind of colonial mastery, and colonial desire, while at the same time denying it. For despite their hyper legibility, the paintings are still impenetrable. The layers of foliage occlude vision, and the unsettling arrangement of space and the weird shifts in scale make you feel like you've entered a world in which you can't possibly belong, physically speaking. Rousseau seems to convey the contradictions and anxieties of the colonial experience in terms of what the viewer can and cannot see. | ||||||

| The exhibition culminated with The Dream, Rousseau's brilliant submission to the Salon des Indépendents of 1910 (fig. 18). Here, the desire implicit in the other jungle paintings is turned outward as a female nude reclines on a red sofa, her body fully displayed to the viewer. Enormous flowers and vegetation surround her, while voyeur-animals encroach from all sides, their eyes peeping through gaps in the foliage. Perhaps more than any other painting, this one makes the loaded meeting of French and foreign its central theme, as the European nude is almost comically at odds with her surroundings. Whether Rousseau was making a particular statement about colonial expansion is unclear, and the organizers were careful to leave these kinds of questions open. | ||||||

| There is much that Jungles in Paris did not address. Questions of race and sexuality, crucially related to the colonialist discourse, were glossed over (though the catalogue does touch on these issues, particularly Christopher Green's excellent essay). Still, with its fantastic documentary material, the exhibition took an enormous step forward in complicating our understanding of Rousseau and positioning his work in relation to notions of the exotic that dominated the colonialist era. Most remarkable of all is that it managed to demonstrate that the exotic is a construct without being overly didactic or ruining the fun of the paintings—without, in other words, stripping the jungle of its mystery. | ||||||

| Martha Lucy Barnes Foundation mlucy[at]barnesfoundation.org |