The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

William Keyse Rudolph and Patricia Brady, eds.,

In Search of Julien Hudson: Free Artist of Color in Pre-Civil War New Orleans.

New Orleans, LA: Historic New Orleans Collection, 2010.

114 pp., 74 color illustrations; no bibliography; index

$35 (cloth)

ISBN: 2010022213

The exhibition catalogue, In Search of Julien Hudson: Free Artist of Color in Pre-Civil War New Orleans, is a welcome contribution to American and French art history, given that there are so few substantial, scholarly monographs on black artists of the early nineteenth century. This is the first such publication on Julien Hudson (1811–44), the second-earliest known portraitist of African heritage to have worked in the United States before the Civil War, following Joshua Johnson of Baltimore (fig. 1). Although enshrined as one of the earliest African American painters, Hudson was not verified as a person of mixed racial ancestry in the historical record until 1995. As author and curator William Keyse Rudolph points out, “his story, in his own life and afterwards, is a combination of detection, speculation, and invention, conducted by researchers, genealogists, and art historians. His artistic reputation rests upon only five secure paintings and a group of attributed works” (21). Given Hudson’s significance, his striking level of transatlantic mobility, and the pioneering research in this exhibition catalogue, it is lamentable that there are only 2,000 copies of the lavishly illustrated study, which has all color images.

Patricia Brady, former director of publications at The Historic New Orleans Collection, wrote the ten-page introductory essay, “Julien Hudson: The Life of a Creole Artist.” She carefully outlines the poignant life of a French-speaking, Catholic painter who died of unknown causes at the age of thirty-three, unmarried and childless. Through scrupulous research of a handful of public documents, Brady determined that Hudson was the oldest son of a British man and a quadroon mother, Jeanne Susanne Desirée Marcos (1795–1854), who was always called Desirée. Hudson’s great-grandmother, known only as Annette, was a black slave belonging to the white Leclerc family. She gave birth to Hudson’s grandmother, a mulatto, Françoise Leclerc (ca. 1752–1829, freed 1772). Brady’s detailed genealogical table of four generations is one of the highlights of the catalogue, making it easy to trace Marcos’s serially monogamous relationships with six white men over forty-five years, and to see when she had thirteen children by five different fathers. Marriage was the most prestigious choice for mixed-race women; Leclerc was exceptional with her series of lovers whom she did not wed.

With financial support from her former master, the merchant François Raguet (who freed her within several years of her purchase), Leclerc bought a cottage in New Orleans. Raguet gave her two slaves and two city lots to care for their daughter. Leclerc had two more children by other, unknown fathers, the last being Hudson’s mother. Although illiterate, Leclerc took care of her family by renting out rooms in her house. Her youngest child, Desirée, had a twelve-year-long relationship with Londoner John Thomas Hudson, beginning at age fifteen. Hudson set up shop in New Orleans as a merchant, then later advertised himself as an ironmonger and ship chandler, but then left the city for unknown reasons in 1822. The couple had four children. Likely with her partner’s support, Desirée bought the house next door to her mother.

There are scant records of Julien Hudson’s life, but it is known that he received a good basic education, perhaps at home or from local Creole men or French immigrants. At thirteen, Hudson began an apprenticeship to a tailor. At fifteen, he took approximately five months of drawing and painting lessons with a Roman miniaturist, Antonio Meucci (active 1818–ca. 1850). At that time, he likely lived with his grandmother, as Brady discovered in Leclerc’s will, which listed Hudson by his nickname of “Pickil.” What Hudson did during the two years after Leclerc’s death is unknown, but in 1831 he advertised himself as a miniaturist and drawing teacher, with a studio address at his mother’s house. By 1830 New Orleans was one of America’s largest cities, with a population of 46,082. Hudson went to Paris twice, first between the summer and late fall of 1831 with his grandmother’s inheritance, and again sometime between 1835 and 1837. Upon returning to Louisiana, he produced portraits and taught George David Coulon, a French-born, white New Orleanian, who became a successful portraitist and landscape painter.

Little else is known about Hudson, who seemingly has no obituary, death certificate, or interment record. Unnatural deaths—suspected homicides and suicides—were not listed in the regular death register. This suggests that Hudson may have been murdered or committed suicide; it is believed that he despaired of recognition. Born five years after Hudson’s death, Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes (1849–1929), the son of free people of color who had emigrated from St. Dominique, learned about the painter from the previous generation and referred to him as “our Titian” in his native French. In his 1911 Montreal publication, Nos hommes et notre histoire (Our People and Our History), he wrote, “We know that Pickhil [sic] produced magnificent pictures, but he has left us nothing as a legacy, perhaps because he became disillusioned. He is said to have executed a full-length portrait of an eminent ecclesiastic, but he destroyed his masterpiece because of vicious criticism passed upon it” (17).

Currently curator of American Art and Decorative Arts at the Milwaukee Art Museum, William Keyse Rudolph was curator of American Art at the Worcester Art Museum when he organized the traveling Hudson exhibition. His essay, “Searching for Julien Hudson,” is divided into two sections. In “An Artist’s Career,” Rudolph places Hudson in the context of local and European artists. In New Orleans, Hudson was one among many documented free artists and craftspeople of color, including sculptors Eugène and Daniel Warburg, marble-cutter and tomb designer, Florville Foy, and lithographer Jules Lion (whose racial heritage is also the subject of current scholarship), as well as cabinetmakers, one in four of whom were free men of color at the time of Hudson’s birth. The publication includes illustrations of work by these men, including Lion’s print of the cathedral of New Orleans (1842) and five of his bust-length portraits, Foy’s marble Child with Drum (ca. 1838), and Warburg’s marble bust of John Young Mason (1855).

Rudolph argues that a recently discovered work, Portrait Miniature of a Creole Lady (ca. 1837–39)—attributed to Hudson based on its New Orleans provenance and resemblance of its female sitter’s features to those of a male subject in one of Hudson’s secure portraits—is strikingly similar to a signed work by his teacher, Antonio Meucci, Pascuala Concepción Muňoz Castrillón (ca. 1830). While Rudolph admits that the Meucci piece dates to his Colombian period, he suggests that this may be an example of the artist reusing a prototype he had already employed in New Orleans and that his student had seen and imitated. Rudolph explains, “provocative artistic and biographical possibilities are easier to suggest than to prove when discussing Hudson’s career” (29).

Rudolph asserts that the voyage to Paris for privileged free men of color was an educational rite of passage, citing the career of Guillaume Lethière (1760–1832) as a “dazzling example of the possibilities that an artist of mixed race could achieve” there (31). Lethière was the illegitimate son of a French man and a freed slave woman from the island of Guadeloupe who followed his father to Paris at fourteen. He won an honorary fellowship to the French Academy in Rome, then rivaled Jacques-Louis David with a competing studio in Paris in the 1790s. Lethière had also Bonaparte family patronage in Spain and Italy. Although slavery in France was not abolished until 1848, it was not legal in the metropolis, thus allowing free men of color there to be worry-free about re-enslavement.

Hudson began to paint on a larger scale when faced with competition by Jean-Joseph Vaudechamp (1790–1864), who arrived in New Orleans from Le Havre in 1832, and subsequently dominated the art market for almost a decade. His success prompted classmates from Anne-Louis Girodet’s Paris studio to emigrate, as well, and Aimable-Désire Lansot, François Fleischbein, and Jacques Amans, worked in the city long after Vaudechamp left. Rudolph argues, “Due in large part to their presence, New Orleans in the 1830s transitioned from a city of miniaturists to a city of easel painters” (37). Fleischbein, although German-born, Gallicized his first name of Franz, for ease with his Creole clients, and Hudson studied under him. Hudson took practical examples from Fleischbein’s Marie Louis Têtu (ca. 1833–36), adopting the background with a low horizon line and generic landscape setting to his earliest-known easel painting, Portrait of a Young Girl with a Rose (1834; fig. 2), and also in Creole Boy with a Moth. Further, he borrowed the pose, with the bent left arm and straight right arm. Hudson likely observed Fleischbein’s difficulty with rendering anatomy, and realized he needed more training. In the mid-1830s, Hudson returned to Paris where he may have studied with Alexandre-Denis Abel de Pujol (1787–1861), although there is no firm documentation of this relationship. Hudson went back to New Orleans in 1837, months after his sister Charlotte had died, and just months before another sister, Françoise, passed away; knowledge of their serious illness may have prompted his return.

In his largest work, a posthumous portrait of Jean Michel Fortier III (1839), Hudson “captures the vivid sense of personality and forthrightness in his sitter”, experimenting with greater detail evident in the notations on sheet music Fortier holds (50) (fig. 3). However, the musician’s paw-like hand suggests that Hudson “had perhaps already realized his full artistic potential” (50). The painting has often erroneously been identified as that of the Fortier’s father, Col. Jean Michel Fortier II (1750–1819), commander of a battalion of free African Americans during the Battle of New Orleans. The sitter had a long-term relationship with a free woman of color, fathering several of her children. Those family members may have commissioned the portrait after his death. Rudolph offers no other biographical information about this genial-looking, dapper white man, with his wavy, graying hair and long sideburns, blue eyes, rosy cheeks, and gold stickpin below a fastidiously thick-wrapped white necktie.

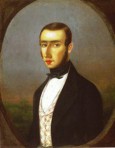

Hudson’s masterpiece is a small work, Portrait of a Man, Called a Self-Portrait (1839), a close-up of which is featured on the cover of the catalogue (fig. 4). The sitter is a handsome young man with neatly combed, reddish-brown hair and chin-length wide sideburns. Rudolph asserts the youth’s distinctive facial features are most striking: “widely spaced, oval, bluish eyes; a long, prominent, curving nose; and pursed cupid’s-bow lips set above a slightly receding chin” (50). The sitter poses at a three-quarter view, bust length, in a fictive-oval surround, a reference to Hudson’s training as a miniaturist. He wears a red-and-white patterned waistcoat, an elegant black jacket, stock, and tie, and poses against a misty, marshy landscape with a low horizon line. Rudolph argues that the figure seems “to inhabit his space rather than seem drawn against it.” He also says the modeling is more assured, lines help to create borders and add clarification, as “delineation unites with plasticity” (52). After making this assured, charming portrait, Hudson tutored Coulon in 1840, and after that he disappears from any references or documentation entirely.

In “An Artist’s Legacy,” Rudolph adroitly analyzes the history of documentation and scholarship on Hudson, beginning with Coulon’s artistic autobiography, a never-published manuscript in which he mentioned Hudson twice. Coulon was the only contemporary commentator on Hudson and the only one who knew him personally. He seems not to have known Hudson’s racial identity or not to have cared about it. The first published commentator to ascribe a race to Hudson was Mrs. A. G. Durno in a chapter on literature and art in Standard History of New Orleans (1900); she calls him “a very light colored man who painted portraits which were much esteemed” (60). As mentioned above, Desdunes then described the sad life of a New Orleans painter of color, Alexandre Pickhil, based on what people remembered about the historic Julien Hudson over fifty years later. In History of New Orleans (1922), John Smith Kendall described Hudson as an octoroon, and in “Historical Sketch of Art in Louisiana” (1935), Ben Earl Looney called him a “negro artist.”

When the portrait of the Titian-haired youth entered the collection of the Louisiana State Museum in 1920, it was listed as Portrait of a Man. However, in 1938, Ethel Hutson, secretary to the board of trustees at the Delgado (now New Orleans) Museum of Art and supervisor of the WPA Art Project, claimed that the work was a self-portrait showing “pronounced Jewish as well as Negroid characters” (63). She had no factual evidence for her assertion, but likely based her analysis on period stereotyping regarding the sitter’s distinct physiognomy. Then the label stuck. Influential art historical monographs by African American scholars, such as James A. Porter’s Modern Negro Art (1943) and Arna Bontemps’s Story of the Negro (1948), repeated the claim, as did ground-breaking exhibition catalogues, from Ten Afro-American Artists of the Nineteenth Century (1967, Howard University Art Gallery) to Two Centuries of Black American Art (1976, Los Angeles County Museum of Art) to Selections of Nineteenth-Century Afro-American Art (1976, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). More recently, in her survey of African American art, Samella Lewis argued that Hudson’s supposed self-portrait “helps depict the flavor and quality of life that was available to many freemen in nineteenth-century New Orleans” (64). In 2006, Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw suggested that the sitter’s features are a possible index of the historically intermediate position between black and white that the artist would have occupied. Rudolph concludes, “These examples reflect broader trends in portraiture scholarship that view the portrait-making enterprise as being a collaborative construction of identity mediated among the triangular relationship of sitter, artist, and viewer” (64). Further, the “unsubstantiated identification has been repeated and built upon, in an endless loop” (67).

Rudolph brilliantly points out that skepticism about the work as a self-portrait “threatens to disappoint viewers by invalidating the painting’s status as one of the oldest surviving images of a sitter of African descent by a painter of African descent” and it takes away “the one tangible success that has been attached to Hudson’s brief career—his recording of his own features.” Such revisionism might undo “one of the best known icons of African American art, even though the painting is unassailably by Hudson” (67).

Rudolph then examines other portraits of Louisiana’s people of color, like Marianne Celeste Dragon (ca. 1795), who passed as white after her marriage, from the school of José Francisco Xavier de Salazar y Mendoza. Such a work, he says, follows “dominant conventions of representation that matter-of-factly represent appearance, rather than Otherness” (71). Even when Hudson depicts sitters who seem to be of color, as in Creole Boy with a Moth and Portrait of a Black Man (aka Portrait of a Man in a Turban) (both 1835), “their skin tones are the only markers that differentiate the portraits from those of his other, supposedly white sitters” (79) (figs. 5, 6).

On this point, I would have to disagree with Rudolph, particularly in the case of the latter work, which features a distinguished elder with bloodshot eyes, white goatee, and gold hoop earring. Despite his Western black suit and tie, his gold and red-striped kerchief, knotted about a scarlet turban, he certainly displays a particular mode of dress specific to an African-derived culture. I sent a digital reproduction of the work to several scholars for comment. Joanne Eicher, editor-in-chief of Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, believes the man may be descended from a Nigerian slave; such headgear was worn by Jamaicans and other Caribbean folk, and was also evident in Brazil. Most distinctive are two long vertical scars (possibly three; the edge of the man’s face near the ear is so deeply shadowed, it’s hard to discern, even in person), on the sitter’s left cheek, a significant detail Rudolph failed to mention. Kate Ezra, a former curator of African art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, suggested that three long vertical facial scars are often a sign of Mande identity. Henry Drewal is sure, though, that these markings are not Yoruba. African art historian Jean Borgatti emailed me that she believes the sitter is of Senegambian descent, and, based on the facial features, Muslim; there were many Muslim slaves who came to the New World. No matter the specific place from which the man hailed, clearly, he is of African descent and deliberately coded to reflect that in this striking presentation. Rudolph does point out, at least, that Hudson’s signature places the work “among a rare group of portraits of people of color made by a person of color” (80).

Tantalizing questions about race and patronage revolve around Hudson’s Creole Boy with a Moth too (fig. 5). The child’s dark eyes, short curly hair, and rosy complexion suggest a mixed heritage. The youth stands at three-quarter angle to his right in a landscape with the horizon level below the level of his shoulders, reminiscent of Fleischbein’s portrait of his wife and exemplified by other European itinerants. Rudolph tells a fascinating story about the painting’s presence at Melrose Plantation, owned by one of Louisiana’s most mythologized families of color, the Metoyers of Natchitoches. A photograph of the work appeared in an album with the handwritten inscription, “Dominic Metoyer/1836,” suggesting that the boy was part of the famous family. The moth, symbol of the soul, in the child’s hand, suggests that this is a memorial portrait. And thus, there is the possibility that one of the wealthiest families of color of the time patronized a known painter of color. As Rudolph suggests, “While patronage might have crossed color lines, it also might have reified them” (87).

As southern art has become increasingly visible, “Hudson has become a convenient name upon which to hang otherwise undocumented works—especially when they depict a sitter who seems to be recognizably of color” (87). Sometimes curators have justified possible attributions to Hudson based on subjects’ skin tone rather than composition. This practice has been more frequent in the art market, where examples are rooted more in stylistic characteristics. Coupled with the fact that Portrait of a Man has been frequently borrowed as a self-portrait and that there are recent sales of attributed work, the point is that Hudson “is a name to include in exhibitions and auction catalogues” (91).

Rudolph concludes that Hudson’s paintings demonstrate the prevalent artistic conventions of their day and that his racial identity “can only be located in his heredity, not in the artworks themselves.” While some might argue that Hudson’s institutionalized racism so affected his construction of himself that he had to subscribe to the dominant culture, “the visual reality is not that simple” and “the history of Louisiana art is overwhelmingly one of artistic exchange with France—an exchange that built upon conversation among artists of all racial combinations” (91). Rudolph’s search for Hudson “reminds us of the possibilities and limits of both the archive and the art of connoisseurship” (92).

The publication also contains reproductions of remarkable ephemera, such as Hudson’s indenture contract to a tailor (1824), Leclerc’s last will and testament (1829), advertisements for Hudson from the English and French editions of Louisiana’s Courier/Le Courrier de La Louisiane (1831), Hudson’s sister’s death certificate (1837), and a cabinet card of Coulon (ca. 1895). For comparison, also reproduced are seven miniatures by Meucci, two Neoclassical paintings by Lethière, portraits by Vaudechamp, Amans, and Fleischbein, drawings and portraits by Abel de Pujol, and paintings of people of color by Americans, such as Thomas Satterwhite Noble, George Fuller, John Lewis Krimmel, Gilbert Stuart, and Joshua Johnson as well as those by several French artists.

For the most part, the publication’s design is elegant and crisp with red chapter headings, subtitles, and titles of works in captions and the exhibition checklist. There are some odd elements, though, such as eight facing pages of near solid hues of red, grey-blue, and tan over brown spots, as though highlighting canvas weave. The use of icons, an empty oval miniature frame above the title of Brady’s biographical essay and a magnifying glass hovering above the title of Rudolph’s analysis of the artist’s career and legacy, is a little hokey. Further, the first part of the study’s title, “In Search of,” is rather tired, reminding one of Elsa Honig Fine’s The Afro-American Artist: A Search for Identity (1973). This places the emphasis on the scholars’ endeavor and biographical lacunas rather than on their firm archival findings and sophisticated analysis of Hudson’s art. Although it does suggest that the quest for identity is ongoing, isn’t that the case with many artists?

This exhibition catalogue is a remarkable piece of detective work and contextualization, and it is the most thorough examination to date on Hudson and his milieu. Since little can be proven definitely about Hudson’s five signed paintings and their histories, the mystery about them will likely persist.

Rudolph also put together a rare and notable, albeit modest, exhibition focused on the work of Hudson and his colleagues that opened at the Historic New Orleans Collection and closed at the Worcester Art Museum. In September, 2011, I viewed the exhibition at the second venue, the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, South Carolina, where Sara Arnold, Curator of Collections, organized the show. Of particular note were two Hudson canvases (Creole Boy with a Moth and Portrait of a Black Man) from private collections that few in the art world knew, as well as a two-figure sculpture of Uncle Tiff and a child by Eugène Warburg (1826–59) added too late to be included in the exhibition catalogue.

The goal of the exhibition was to explore a series of antebellum paintings and the history of free people of color in New Orleans, as well as the ways in which issues of race, class, and ethnicity defined, and perhaps limited, Hudson’s artistic production. For the most part, the curators succeeded in meeting that goal. Unfortunately, this was not a handsome installation.

The exhibition took place on the second floor of the Gibbes Art Museum, in three galleries that have seen better days. The central hall, featuring the introductory text and Portrait of a Man (1835) by Hudson has high ceilings with peeling paint. The grey, wall-to-wall carpeting is worn and so loose that there were multiple, long ripples high enough on which to trip. The lighting was poor and not directed at the art; there were two large chandeliers each with seven large light-bulbs and a series of two-bulb wall sconces. These features, and three large windows with closed blinds, suggest that this was a grand room for receptions rather than the display of art. The orientation in this large, and mostly empty, space was slightly confusing; one did not know whether to head first into the left or right smaller flanking rooms.

Despite the awkward and rather unattractive installation and museum setting, this was a significant display that gathered together, for the first time, all known and attributed paintings by Julien Hudson. Rudolph greatly enhanced our understanding of those seven small images by contextualizing the artist’s life and career in terms of work by his mentors and contemporaries, producing a remarkably balanced and interracial exhibition of early nineteenth-century American and European art in Louisiana. Based on path-breaking archival research and visual analysis, this endeavor was a valuable contribution to art history and the catalogue is sure to be required reading in courses on African American art, if not also in integrated classes on American art.

Theresa Leininger-Miller

Associate Professor, Art History

University of Cincinnati

theresa.leininger[at]uc.edu