The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

|

The Ecstasy of Decoration: The Grammar of Ornament as Embodied Experience |

|||||

|

|

|||||

| First published in 1856 and reprinted in numerous languages ever since, Owen Jones's Grammar of Ornament sets out to establish firm principles designers should adhere to in order to make their work (1) better conform with the ends or functions supposedly served by the decorative object and (2) better conform to commonly accepted standards of taste and beauty.3 In formulating such principles, Jones was reacting to a widely perceived crisis in British design, in the years immediately following the Great Exhibition of 1851, when form was seen as having become too detached from function, and design was perceived as being too riotously neglectful of rules of taste and decorum. "The absence of any fixed principle in ornamental design is most apparent," wrote the painter Richard Redgrave in reviewing the Great Exhibition for the Journal of Design and Manufactures.4 "The mass of ornament applied to the works...exhibited is meretricious," he concluded in his official Supplementary Report on Design.5 "The taste of...producers in general is uneducated," wrote Ralph Wornum in "The Exhibition as a Lesson in Taste."6 The Grammar of Ornament thus sets out to redeem Victorian design from the condition into which it had sunk, in the eyes of its critics, and to clarify its mission—both moral and aesthetic—in the eyes of an industrial plutocracy desperate to make decoration a critical weapon in the fight to achieve supremacy in the market for industrial goods. | ||||||

| Jones formulates these principles in a list of thirty-seven axioms or "Propositions" prefacing The Grammar of Ornament, where they constitute something of an artistic manifesto (see Appendix). This list has been called "the pedagogical core of the book, the grammar of The Grammar,"7 and was quickly adopted as an official credo by the design establishment of mid-Victorian Britain. The list remains in print to this day, quite separate from The Grammar of Ornament, not least because it helped define the profession of industrial design as such and constrained decoration as never before to the ends of the "consumable" object.8 However, Jones wanted these axioms to be understood not as arbitrary attempts to legislate rules—though this, it has recently been argued, is exactly what they are9 —but as systematic and scientific attempts to deduce the fundamental "laws" of decoration according to a massive program of comparative research. The rhetoric Jones employs to present his Propositions thus diminishes their specific and controversial character at the same time as it makes them appear far from arbitrary attempts to legislate long-disputed matters of taste, beauty, and artistic purpose. Jones achieves this illusion of objectivity in two ways. | ||||||

| First, as its title suggests, The Grammar of Ornament promises simply to equip the aspiring designer—whether architect, illustrator, craftsman or industrial designer—with a formal set of tools for the practice of design, much as a grammar (nowadays called a "manual of style") promises to equip the modern student with principles on which successful writing and speaking might be based. Though at first sight Jones's work presents itself as a riot of brightly colored decoration and as a rather confusing compendium of "the most prominent types in certain styles" of ornament, it is not the "individual peculiarities" of those types and styles that matter finally, claims Jones in his Preface to the Folio Edition, but the "general laws" those styles can be said to embody.10 The principles established by his work, Jones maintains, are the universal truths ("general laws") of decoration, independent of considerations of context, culture, and history. | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Second, once we turn from the work's title to its Preface as such, Jones presents his Propositions in such a way as to make them appear a logical distillation of the principles (for to him, such principles were the only principles) apparent in the color plates of The Grammar, which comprise hundreds of reproductions of decorations from a range of cultures and historical periods, printed in colors of exceptional brightness and accuracy for their day. (To a certain extent, these principles are also made explicit in the textual commentaries accompanying each plate in The Grammar of Ornament, written by Jones himself in conjunction with a small circle of friends and experts, some of which adhere closely to the Prefatory Propositions in tenor and language.) But the basic structure of The Grammar of Ornament is an imagined dialectic between color plate and Proposition—between illustration and text—in which the Propositions represent the distilled essence, for cognitive purposes, of the experience embodied in the book's stunning color plates. This much is clear simply from the title Jones gave to his list of Propositions: "General Principles in the Arrangement of Form and Colour, in Architecture and the Decorative Arts, Which Are Advocated Throughout This Work." In the sense that Jones saw them as the intellectual core of his work, the general principles announced in these thirty-seven Propositions, as Rhodes suggests, themselves constitute Jones's "grammar" of ornament. | ||||||

| From the title Jones gave to his Propositions it will be immediately obvious that Jones's remedy to the problem located by critics such as Wornum and Redgrave lay in defining decoration along formal lines in terms of the "arrangement of form and colour." The Grammar of Ornament represents one of the first and most sophisticated expositions of visual formalism in the English language, and it had a discernible influence on the work of Roger Fry and Clive Bell in the early twentieth century. But for the time being, simply noticing the conjunction of form and color in the Propositions' title, as well as their joint subservience to purely spatial considerations (or "arrangement"), alerts us to the unique contribution Jones made to the Victorian discourse around decoration. Where the theories Ruskin had advanced in The Seven Lamps of Architecture and The Stones of Venice proved difficult to comprehend and to implement,11 accessible only to a select few (like William Morris) sympathetic to Ruskin's revolutionary tendencies, Jones's Propositions had the virtue of a proverb-like simplicity and a sleek practicability. I shall be arguing in this essay that the formalism that they announce in fact masks, for ideological purposes, a more provocative understanding of decoration, with far-reaching social implications, centered on the effects of color. One important byproduct of Jones's attempt to "illustrate" his general principles was the harnessing of color as never before to the medium of print, virtually inventing the printing process known as chromolithography in order to produce his book's color plates. In my view, it was this adaptation of color to the print medium, liberating the minds and eyes of Victorian readers, that constitutes Jones's real and most enduring achievement. But at this point, there can be no disputing that in the eyes of Jones himself and the British design establishment, for whom and by whom The Grammar of Ornament was made to serve in British design schools, Jones's achievement lay in his challenge to the humanistic tradition and in his attempt to put both the study and practice of decorative design on a secure scientific basis. | ||||||

| In the view of his contemporaries, then, it was the brilliance of Jones's formalist theory that made him the most influential Victorian theorist of decoration. "By pen and pencil ceaselessly and enthusiastically exercised during nearly half a century, Owen Jones has left a mark upon our age which will not be soon effaced," wrote the Art Journal on Jones's death in 1874; "it would be impossible to mention the name of any one whose genius and taste combined have had a greater influence on the decorative arts of this country."12 "No man did more than he," commented the Arts-and-Crafts designer Lewis F. Day in surveying "Victorian Progress in Applied Design" in 1887, "towards clearing the ground for us, and so making possible the new departures which we have made since his time. The influence of Ruskin, and of Pugin before him, counts also for something, but I attribute even more weight to the teaching of Owen Jones."13 Jones "has had the honour of being our principal deliverer, in the period of modern taste, from the dominion of sprawling floral patterns, in apparent relief, on our wall papers and carpets, and of pointing out and exemplifying the superior beauty and fitness of smaller and more geometrically constructed designs," remarked The Builder in 1874: "His rules... have been accepted and acted upon almost universally by our best decorators."14 "As a theorist rather than as an artist... his influence was immense" (187), summed up Day a decade after Jones's death. That influence is clear, perhaps, simply in the titles of the series of books published in the 1860s and 1870s by Jones's disciple Christopher Dresser: Principles of Decorative Design, The Art of Decorative Design, The Development of Ornamental Art in the International Exhibition (subtitled "a concise statement of the laws which govern the production and application of ornament"), Studies in Design, and (in America) General Principles of Arts, Decorative and Pictorial. As their titles indicate, Dresser's works owe a heavy debt to Jones's ideas, which they served to make popular at a time when the South Kensington school was coming under heavy criticism from those most closely associated with Ruskin.15 Similarly, when William Morris writes that "definite form bounded by firm outline is a necessity for all ornament" or that "a recurring pattern should be constructed on a geometrical basis" he is attesting to the influence of Jones's ideas on his own imagination—and indeed on that of the Arts-and-Crafts Movement generally—an influence that has been minimized, in traditional histories of decoration and design, in the rush to see Morris as the historical disciple of Ruskin.16 | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| When modernist historians examined the Victorian literature of design in the middle years of the twentieth century, it was this success in disseminating formalist design principles that was most heavily stressed—no doubt because, to the modernist imagination, such success seemed to establish the science of design itself on the surest intellectual credentials. Nikolaus Pevsner, for instance, sees Jones as an important—if neglected—source of ideas for modern architecture and design, applauding the Propositions as a whole and reprinting the most "generally important" ones.17 Jones and his circle, he comments, "developed a program of remarkably sound aesthetics" and "as writers on architecture and design, their position is central."18 Similarly Alf Boe, in tracing the origins of the idea of "functional form," describes Jones's Propositions as "the ultimate codification of principles developed since the first Parliamentary Committee was established to look into the question of Industrial Design in England in 1836." "Seen as a unity," Boe remarks, "Jones's propositions represent an intellectual construction built on research into phenomena in nature and art, and carried out in a scientific spirit of analysis."19 | ||||||

| To a certain extent, this has remained the dominant tradition in what little criticism of The Grammar currently exists. The Grammar is still seen by some commentators as a pioneering work of modernism and as the ultimate embodiment of now widely held design principles, centered on function and form, grounded in the widest comparative research. David Brett, for instance, has recently called The Grammar "one of the founding documents of aggressive modernism."20 And John Kresten Jespersen sees The Grammar as founding a "revolutionary style of ornament" and as advancing as never before a concept of decoration, still hegemonic today, "as flat patterned motifs on a field surrounded by borders."21 The kind of "conventionalized field design which Owen Jones proposed in The Grammar," writes Jespersen, constitutes a "priceless theory" and the "ideal starting-point" for the "visual[ly] exciting ornament of this century" (118). More than any other mid-Victorian theorist, Jones succeeded in grounding decoration in the idea of style or form, Jespersen argues in effect, thus preparing the way for the idea of the historical development of style (or Stilfragen) that helped constitute the discipline of art history in the work of Riegl and Wolfflin, both of whom use decoration as the basis for an argument about visual art per se. | ||||||

| Yet the very repetition of Jones's own formalism in the critical literature devoted to him should alert us to certain problems here. The modernist tradition views Jones as a formalist thinker, one suspects, largely because doing so legitimates the formalism underpinning modern design itself. Clearly Jones has been, to this day, remarkably successful in equating decoration with the idea of form or style—as can be seen in the words of those (quoted approvingly by Jespersen) who attribute to Jones the "geometrical style" or "geometrical mania" of mid-Victorian design.22 Yet Jones's practical influence can be described in terms of color and perception as much as in terms of form and function. In this respect, it is conspicuous that the critical literature on The Grammar generally (1) dispenses with Jones's preferred term ornament in favor of the more practical and utilitarian term design and (2) places a heavy premium on Jones's thirty-seven Propositions at the expense of his practical achievements. | ||||||

| These assumptions have nonetheless come into question from a number of quarters in recent times. One of those quarters is the domain of printing history. Book historians such as Ruari McLean and Joan Friedman, in assessing Jones's importance for the history of printing and the book, dispense quickly with his sometimes pretentious ideas for The Grammar of Ornament in order to focus upon Jones's achievements in the field of printing and, in particular, on his development of chromolithographic technology for the reproduction of decoration in accurate, bright color. That is to say, book historians typically treat The Grammar of Ornament as an illustrated or decorated book, not as a formalist treatise. As such, book historians offer an important corrective to a generation of design historians keen to inscribe Jones within the founding narratives of modernism, for whom Jones's "Propositions" on design are a document of the highest importance. | ||||||

| Recent histories of decoration, written in the wake of Pevsner and Boe, have also begun to question the importance of Jones's Propositions and the formalism they inscribe. Ernst Gombrich, for instance, demurs at Boe's judgment and calls Jones's Propositions "vague and even vacuous," adding that "this fault is amply made up in the analysis of individual designs."23 For Gombrich, The Grammar is unquestionably a "classic of our field," but the core of the work lies not in the Propositions so much as in the textual analysis accompanying each plate, where Jones displays a "psychological acumen" (53) hitherto absent from the debate surrounding decoration. Similarly, Isabelle Frank has recently argued that The Grammar is indelibly fissured by the contradictory impulses of scholarship and "artistic practice." Like Gombrich, she sees The Grammar of Ornament as having "challenged and transformed some of the aesthetic assumptions that lay at the heart of nineteenth-century studies of art" (249). But unlike him, she sees The Grammar as unduly "dominated" by textual commentaries meant finally to point up the formalist principles enshrined in the Propositions: "although the historical sections merely support the principles... presented, they nonetheless end up dominating" the work as a whole: "Jones's Grammar ... straddles the worlds of artistic practice and of scholarly investigation" (249). Frank's judgment, which is lamentably brief, is prefigured in the work of John Grant Rhodes, whose unpublished doctoral dissertation on "Ornament and Ideology" remains one of the best scholarly contributions on Jones. While agreeing with Boe that "the Propositions constitute the most succinct presentation of the Schools of Design theory," Rhodes nevertheless finds them "an uneven and strangely weighted lot," lamenting that they "necessarily reduce the theory to pedagogical dicta" (217). For Rhodes, Jones's Propositions can never quite capture the complexity of the theory that lies behind them. Even more problematically, they are difficult to reconcile with the fundamentally visual impulses they are meant to embody and that are best summed up in The Grammar's color plates. "For practical purposes, the plates have tended to subvert, as Jones feared they would, the message of the text," Rhodes observes: "the main feature and, for most of its readers, the principal attraction of the book are its one hundred and twelve plates of illustrations, in which a wide variety of historical ornament is reproduced in color lithography of very fine quality for its day" (215-16). | ||||||

| Rhodes's criticism is key, and the remainder of this essay will be concerned with drawing out its implications: Has the official history of British design been justified in stressing the formalist impulses in Jones's work, summed up in the Propositions with which Jones prefaced The Grammar? Or is Jones's work better understood by attending to the color plates originally intended to serve (or "illustrate") the principles made explicit in the Propositions? Answering these questions is of immense importance for assessing the notion of decoration and its importance to the Victorian imagination. Where the first argument would view The Grammar of Ornament as an illustrated book, its decorative elements merely "illustrations" to arguments one can isolate in language, the second view sees The Grammar of Ornament as a decorated book (perhaps better titled An Ornamented Grammar) in which the experience of viewing the illustrations—now freed from their function as structural supports to a formalist argument—constitutes an end in itself, separate from the merits of Jones's conceptual claims. The second argument, in other words, implies that the "text" of The Grammar serves an ideological function in constraining decoration to narrowly circumscribed purposive ends, limiting its role to that of "illustration," while at the same time suggesting that The Grammar has traditionally lent itself rather too easily to the agenda of those who put it to use in the design schools. Certainly Jones himself must be held partly responsible for harnessing The Grammar to this agenda—in part through the Propositions, in part through the textual commentaries accompanying The Grammar's plates, and in part through his personal involvement with the circle around Sir Henry Cole, founder of the South Kensington Museum (later the Victoria & Albert Museum) and head of the Department of Practical Art, with direct responsibility for Britain's art and design schools. But as the recent commentaries just quoted suggest, The Grammar is not reducible to the sum of the uses to which it has been put, and it escapes the enslavement of illustration to text as much as it enforces it. If The Grammar has for too long been understood as an illustrated book epitomizing the inevitability of a narrowly formalist concept of design, this has as much to do with the institutions in, and for, which The Grammar was made to serve as it does with the agenda of its individual author. | ||||||

| Assessing Jones's contribution to Victorian notions about decoration, then, requires us to deconstruct the formalism Jones's work—on one level, at least—would inscribe. Rather than seeing The Grammar's importance as lying in its illustration and consolidation of design principles, at once functionalist and formalist, subsequently adopted by modernism, I see the importance of Jones's work as lying in his unprecedented adaptation of colorful decoration to the textual demands of the printed book. The implications of this achievement were far-reaching: Jones liberated color and decoration from the straightjacket of representation, contributing massively to the nineteenth-century "reorganization of vision" recently identified by Jonathan Crary;24 and he unwittingly exposed the activity of the eye in the processes of cognition, awakening us to something in the nature of decoration that had eluded his formalist calculations. Decoration, The Grammar of Ornament ultimately suggests, operates at the level of active experience far more than at the level of cognition and intellect. Partly for this reason, it can never be a vehicular form—even a vehicle for the demonstration of formalist principles—because unlike representational painting or the novel, there is no "content," message, or form to separate from the decorative medium. We can see this simply in the ways in which The Grammar of Ornament eludes its author's intentions for it. So successful was Jones in adapting decoration to the constraints of the book that he undermined the functional-formalism he meant decoration to illustrate, turning the usual relation between text and illustration on its head, and emphasizing the book's visual components at the expense of its verbal "message." Certainly precedents exist for The Grammar of Ornament in the brilliantly illuminated manuscript books of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance. But Jones brought such "textualized" decoration to a broad readership, virtually inventing color mass-printing in the process, a feat that would in turn precipitate a virtual explosion of decorated mass-printed texts—books, calendars, playing cards—later in the nineteenth century.25 This textualization of decoration, however, was by no means a fully conscious process on Jones's own part. As the curiously hybrid form of The Grammar might suggest, its author was deeply conflicted about the nature and meaning of decoration, masking his basic impulses in a number of ways, with powerful implications for discussion of The Grammar in the twentieth century. Assessing Jones's achievement in The Grammar, then, requires us to look first at the strategies Jones employed to "rationalize" decoration, disciplining it so as to conform it to the functional demands of an industrialist plutocracy, as much as at Jones's decorative experiments with ink, paper, and the lithographer's stone. | ||||||

|

II |

||||||

| Of the thirty-seven propositions prefacing The Grammar of Ornament (see Appendix) the vast majority concerns principles of form and construction. Twenty address questions of color in order to show how color may be adapted to the requirements of form and balance; and eleven of the first thirteen propositions emphasize considerations of visual form alone. Jones's formalist bias is especially clear in the first eleven propositions, where aesthetic value is defined largely as a matter of spatial arrangement or "harmony." Here both Jones's language and his argument prefigure ideas expressed by Roger Fry and Clive Bell in the seminal texts of twentieth-century formalism.26 Whereas Bell was to distinguish "significant" from insignificant form, it is noticeable that Jones's notion of form encompasses the visual whole; "there are no excrescences; nothing could be removed and leave the design equally good or better," he states in Proposition 6. Bell and Fry would allow for the discriminatory power of the artist and the beholder in judgments about what constitutes "significant" form. But Jones defines form as a matter of spatial arrangement and proportion alone. Decorative form thus appears, in his estimation, to be value-neutral, determined by scientific and mathematical precepts that are free of human judgment. Conspicuously, Jones abolishes from consideration anything that smacks of subjectivism and attempts to ground his Propositions on premises that are scientific and objective. One notices especially his italicized appeal to "Natural law" as verification of the principle that "all junctions of curved lines with curved, or of curved lines with straight, should be tangential to each other" (Proposition 12). Like the organicist metaphor structuring Proposition 11 ("In surface decoration, all lines should flow out of a parent stem. Every ornament, however distant, should be traced to its branch and root"), this appeal serves to "naturalize" formalist principles, anticipating the arguments of W. G. Goodyear, Alois Riegl, and others that the history of decoration is more or less synonymous with the study of plant forms.27 As Jones puts it in the Preface to the Folio edition, "whenever any style of ornament commands universal admiration, it will always be found to be in accordance with the laws which regulate the distribution of form in nature" (2). This attempt to ground formalist principles in "natural form" would become most pronounced in The Grammar of Ornament's concluding chapter on "Leaves and Flowers from Nature," though it is echoed in isolated claims in earlier chapters, such as in the idea that the ancient Greeks obeyed "the three great laws which we find everywhere in nature—radiation from the parent stem, proportionate distribution of the areas, and... tangential curvature of the lines" (33) or "the Egyptians...instinctively obeyed the law which we find everywhere in the leaves of plants" (24). This organicist line of thinking may owe much to Jones's reading of Ruskin, who in The Seven Lamps of Architecture, and still more in The Stones of Venice, had argued that decoration should be based in the "true forms of organic life" and in "the most frequent contours of natural objects."28 Over the ensuing years, such reasoning would be developed considerably by Jones's disciple Christopher Dresser29, and it can be linked here to the argument about "conventionalizing" representation for the sake of formal unity, summed up in Proposition 13. | ||||||

| A similar attempt to validate formalist principle on higher grounds can be seen in Jones's italicized appeal to "Oriental practice" in Propositions 11 and 12. Like his allusions to "natural law" and the burgeoning natural sciences, this appeal plays into Victorian Britain's deepening uncertainty about its own practices by alluding to an "Orient" that many Victorians were beginning to see as the seat of a higher truth and beauty. Since the romantics' "discovery" of "the East," Asia and Islam had unsettled Britain's confidence in its own cultural mission; in his previous work, The Alhambra, published at a time when Parliament was actively inquiring into the condition and future of British design, Jones had held up Moorish design—as he would do once again in the chapter on "Moresque ornament" in The Grammar of Ornament—as embodying a beauty never achieved in Britain. Like his italicized commentary "universally obeyed in the best periods of Art, equally violated when art declines," then, Jones's appeal to "Oriental Law" plays into a deep-seated uncertainty about the historical mission of Victorian England, accelerating fears of decline that Jones had himself already done much to stoke. | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| The formalism apparent in Jones's first eleven Propositions is present in the twenty propositions on color that immediately follow them too, all of which look forward to Clive Bell's argument that "the distinction between form and colour is an unreal one" and its accompanying contention "when I speak of significant form, I mean a combination of lines and colours" (19-20). Especially striking is Jones's collapsing of chromatic principles into spatial considerations of form and arrangement. This tendency leads Jones in turn to emphasize the principle of edging or "outline" by which one color might be demarcated from another. (This is one of the areas, as I mentioned earlier, in which Jones had a marked effect on William Morris.) Materials, methods, and the symbolic possibilities of color do not enter into consideration, as they do in Ruskin's writings on color,30 because for Jones, color is determined by the operation of formal laws alone. Jones seeks to ground this approach, moreover, by direct appeal to optical science—by allusions to "Field's Chromatic Equivalences" and (in a marginal note) to "the law of simultaneous contrast of colours, derived from Mons. Chevruil [sic]"—much as he had alluded to Oriental Practice and Natural Law in validating his Propositions on form alone. | ||||||

| The formalism apparent in Jones's propositions, finally, goes hand in hand with a functionalist concern for the "object" or end that decoration must be made to serve. This concern is clearest in Proposition 13, with its concern for the "unity of the object" decoration is "employed to decorate." But it is implicit too in Jones's first five propositions on the link between decoration and architecture.31 For instance, Proposition 1 ("The Decorative Arts arise from, and should properly be attendant upon, Architecture") and Proposition 5 ("Construction should be decorated. Decoration should never be purposely constructed.") both promote the idea—later to be understood as functional form—that decoration should be subservient to the building or "construction" as a whole.32 (In this respect, Boe's recognition of a "growing perception" among Victorians "of beauty in the functional and non-representational character" of line, form, and color [137] applies to Jones as much as it does to Dresser, with whom Boe associates this perception.) Jones's published lectures make clear that "no true beauty can exist which does not in some way spring from the useful."33 Truth and beauty are wholly elided with utility in his imagination, as he makes explicit in the claim "Every object, to afford pleasure, must be fit for [its] purpose and true in its construction." (21) Complaining at the tendency of architects to employ Gothic, Egyptian, and Moorish elements on suspension bridges and railway architecture, he writes in his lectures that "new materials" and "new wants to be supplied" should suggest forms "more in harmony with the end in view" (14). | ||||||

| III | ||||||

| At this point I want to shift the grounds of my argument slightly and discuss Jones's attempts to illustrate these principles in the color plates of The Grammar. The color plates to The Grammar constitute Jones's most significant attempt to validate these principles, not least because, by the simple expedient of attaching commentaries to his plates, Jones disguises their "illustrational" intent and suggests simply that they represent the raw data from which his principles are scientifically derived, in effect, claiming that the Propositions "illustrate" the color plates rather than vice versa. | ||||||

| Since Jones's color plates have until recently proved cumbersome and expensive to reproduce, a brief word is in order about their nature and origins. Quite apart from any illustrational function within The Grammar of Ornament as a whole, the color plates that go to make up the bulk of Jones's volume are among the earliest and finest examples of chromolithographic printing, a technology—specifically invented by Jones for the color reproduction of decoration—used widely in the second half of the nineteenth century for printing in multiple colors or "polychromy." Book historians agree not only that "one of the greatest monuments of colour printing in the nineteenth century was Owen Jones's The Grammar of Ornament" but also that the printing process Jones developed was perfectly suited to the kinds of decoration Jones wished to illustrate.34 If ever there was a question about the technical suitability of the kinds of decoration proposed by Jones for the new media of industrial society, that question was definitively answered by the skill with which Jones and his associates produced his book's color plates. In the plates, various historical styles of decoration are reproduced with exceptional clarity and color through the medium of chromolithography.35 This mode of printing "seems to have been invented to do justice to the gorgeous subject," a reviewer for the Quarterly Review had written.36 "Distribution of form" and "the arrangement of form and colour" go to the very heart of the chromolithographic process, in which the image is first separated into its composite elements then built up incrementally through the application of successive blocks of color. No other medium was (or is) so well suited for reproducing the kinds of decoration Jones wished to illustrate, since in the very accidents of printing, chromolithography made visible the formal principles on which decoration appears to be constructed with an immediacy and a naturalness other print technologies could not rival. Consequently, as Ruari McLean comments, "The Grammar of Ornament is still a superb picture-book: but in the 1850s it was the first time in England that any systematic and serious reproductions in colour of historical ornament had ever been printed" (122). | ||||||

|

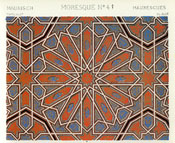

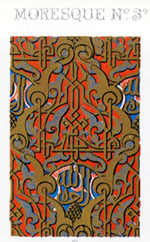

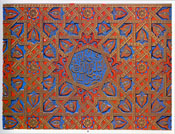

This apparent harmony between the print medium and decoration itself can be seen clearly in some of the plates used to illustrate the chapter on Moresque; in these plates the fundamental tenets of The Grammar seem accentuated by the printing process as much as by the ornamental style itself. Jones's rules for the use of the primary colors, for instance, are underscored as much by the requirements of lithography, in which secondary and tertiary colors are generally produced (if at all) only by successive printings of blocks inked in the primaries, as by "Moresque" considerations. Similarly lithography's predilection for blocks of primary color, produced in succession to one another, lends itself readily to Jones's proposition that "colors should never be allowed to impinge upon one another." As David Pankow comments, "every colour in Jones's complex designs had to be mechanically separated by the chromolithographer."37 While it is certainly possible to produce subtle gradations of color lithographically through the superimposition of one or more colors upon another, the process nevertheless lends itself most readily to primary colors "in the raw," as can be seen from the distinctness with which red and blue are printed in Plate 42 (fig. 1). |

||||||

| Figures 1, 4 and 5 nicely illustrates Jones's propositions about edging. Indeed, chromolithography's accidental tendency to reveal a white line or "ground" in between blocks of color not married together perfectly,38 for fear of superimposing one color on another (see figs. 2 and 3) only accentuates the "edging" deliberately introduced into certain plates to illustrate Proposition 29 (see figs. 4 and 5). The unevenness with which the blocks of green, blue, gold, and pink have been printed in Figures 4 and 5, leaving unequal amounts of unlinked paper exposed on each side of them, while lamentable on technical grounds and no doubt faithless to the Moorish originals, nonetheless serves to accentuate the principal of edging itself, which might easily have gone unnoticed if the printing had been more perfect. | ||||||

| Finally, lithography lends itself especially to the formal and spatial considerations Jones wished to emphasize since, in tracing the object or decoration to be printed onto the template or "key-stone" from which the first pressing will be made, the artist is required to make a detailed abstract or stencil "not only giving the outlines of the object of composition, but also minute indications of the boundaries of all colours, lights and shadows."39 While this requirement by no means restricts chromolithography to sharply defined masses and lines, it nonetheless suggests that the process is best suited to those forms (see fig. 1) that are most easily and accurately traced, to flat Euclidean forms based on geometrical principles, as well as to those containing symmetrical repetitions of a single motif, since the same stencil might be utilized more than once to reproduce multiple instances of the identical motif with an accuracy and speed unattainable with less formal images. | ||||||

|

Yet if lithography seems to lend itself perfectly to the ornaments Jones wished to illustrate, embodying through its technical requirements those laws of form and color made explicit in the accompanying "text," it nonetheless threatens to subvert the claims of that text through the very perfection and novelty of its medium, sharply exposing the idealism underpinning Jones's theoretical rigor. It is conspicuous, in this respect, that early reviews of The Grammar concentrate on the work's technical achievement at the expense of its verbal text or the theoretical principles it was meant to embody:

This review, published in the Art Journal, perfectly exemplifies Rhodes's comments that "the principal attraction of the book are its one hundred and twelve plates" and that "for practical purposes, the plates have tended to subvert...the message of the text." The reviewer directs his praise at the plates themselves, not at the all-important principles they embody, emphasizing the sheer beauty and pleasure of ornament where Jones would have us attend to laws of form, arrangement, color combination, and so forth. The review effectively reclaims The Grammar from the idealist assumptions underpinning it, returning decoration to the world of praxis and things, as if determined to corroborate Clement Greenberg's maxim "Art is strictly a matter of experience, not of principles."41 |

||||||

| This was a problem that Jones had foreseen. In his Preface to The Grammar, Jones expresses a hope that his book might spur the invention of an original Victorian style, thereby stemming "the unfortunate tendency of our time to be content with copying, whilst the fashion lasts, the forms peculiar to any byegone age" (1). Yet in the very process of expressing this hope, Jones confesses "it is more than probable that the first result of sending forth to the world this collection will be seriously to increase this dangerous tendency, and that many will be content to borrow from the past those forms of beauty which have not already been used up" (1-2). The very excellence with which Jones had reproduced extinct and hitherto inaccessible styles of decoration threatened to revitalize them—to confuse the "results" of decoration for the "principles" it embodies, as Jones puts it in his published commentary—and so undermine Jones's claim to be deducing general laws for the benefit of Victorian design.42 As Rhodes sees it, "undoubtedly this is what happened. The Grammar became most widely known and used—as it is said to be so used still—not for its exposition of the Schools of Design Theory, but as a "crib-book" deluxe for designers of ornament" (216). | ||||||

| This might seem a pedantic point. But the early reviewer's "mistake," which is built into the very structure of The Grammar of Ornament, dramatizes a confusion about the nature of decoration. Whereas Jones seems to have wanted to subordinate decoration to the rational purpose of "illustration," conscious of the eye's power to subvert the careful deliberations of mind and reason, the Art Journal reviewer insists on seeing decoration as inseparable from the experience embodied in the act of perception, emphasizing precisely those concrete and affective qualities about which Jones himself was most suspicious. Paradoxically, the plates to The Grammar were intended as secondary elements in the book's internal order, meant to exemplify principles made explicit in the accompanying text, not as sources of pleasure, inspiration, and wonder. Yet in his introductory comments—and still more, in his practical devotion to the business of book design, as manifested in the brilliance of his chromolithography—Jones indicates that he was perhaps aware that his book always threatened to escape its "illustrational" mission. | ||||||

| In this respect, what is most instructive about contemporary reviews of The Grammar is not what they say directly about The Grammar as a treatise but the note of excess that creeps into their language. "We are almost astounded," comments the Art Journal; Jones's work is a "marvel," exhibiting "the utmost brilliancy and delicacy." A "more valuable publication for the instruction and gratification of the man of taste... has never been put forth in any age or country." It is "beautiful enough to be the hornbook of angels," summed up the Athenaeum: "the book is bright enough to serve a London family in summer instead of flowers, and to warm a London room in winter as well as a fire."43 The very brilliance of Jones's printing technique—mastering the centuries-old goal of mass-printing in color while demonstrating the formal properties of color in combination and juxtaposition with one another—brings a principle of excess to bear, accelerating The Grammar beyond Jones's own intentions for it and calling attention to the medium as an end in itself. Not surprisingly, The Grammar sparked a range of Victorian imitations and "a new industry" in color printing, claims McLean, and it was quickly made available throughout Europe in a variety of formats. This tendency reaches its culmination, in our own day, in the electronic "hypermedia" edition of The Grammar of Ornament recently published in CD-Rom format, where Jones's formalist Propositions and textual commentaries are dispensed with in favor of making the plates available in more "exquisite clarity" and "in progressively higher resolution" than has ever been achieved before.44 | ||||||

| Jean Baudrillard would see this "haemorrhaging of value"45 as constitutive of postmodern culture. We live in an age marked by "this ex-centricity of things, of this drift into excrescence" (FS 188), Baudrillard writes, when "every trait" gets "raised to the superlative power, caught up in a spiral of redoubling" (FS 9), like "light... captured and swallowed by its own source" (FS 17). Ever seeking for forms of communication "faster than communication," for "the model...more real than the real" (FS 186), postmodern culture is characterized by "a vertiginous over-multiplication of formal qualities" (FS 187) and by the rise of "ecstatic" forms that "elude the dialectic of meaning" (FS 185), "spiraling in" on themselves until they have "lost all meaning, and thus radiate as pure and empty form" (FS 187). Yet it is clear from my analysis that this process began long ago, and that in the process of trying to "realize" ornament, Jones succeeded only in calling attention to ornament's thoroughly mediated condition, in which the truth about ornament becomes inseparable from a truth that resides in the act of seeing itself. | ||||||

| In this respect, Jones's achievement in The Grammar of Ornament can be linked to Walter Benjamin's well-known comments in "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" on the role of new media in constructing new paradigms for perception. Benjamin writes that the "manner in which human sense perception is organized, the medium in which it is accomplished, is determined not only by nature but by historical circumstances as well.... The history of every art form shows critical epochs in which a certain art form aspires to effects which could only be fully obtained with a changed technical standard, that is to say, in a new art form. The extravagances and crudities which thus appear, particularly in the so-called decadent epochs, actually arise from the nucleus of its richest historical energies."46 New media have the potential to "burst this prison-world asunder," writes Benjamin, to "reveal entirely new structural formations of the subject" (236) by making us conscious of a "different nature" (236) distinct from the world we previously took for granted. | ||||||

| The liberating potential Benjamin describes is palpable, I would suggest, in Victorian reviews of The Grammar; suddenly perception obtains the "utmost brilliancy and delicacy," causing the scales to fall from reviewers' eyes and making the book appear a "marvel."47 Yet there is a sense too in which Jones's achievement lies not simply in broaching a new perceptual paradigm but in shifting the emphasis—in a work that claims to embody the highest truth and thus appropriates a scientific prerogative for itself—from cognitive modes of understanding to aesthetic and perceptual ones, in which truth comes embodied in objects that strike our eyes and engage us through the five senses. In this sense, there is what Benjamin calls an "unconscious optics" (237) to The Grammar as well as a conscious one. Gombrich is certainly correct that Jones employed the psychology of perception in framing his ideas about decoration, bringing "to the debate a criterion which had been lacking" previously (51). But the color effects produced by the plates, and still more the after-images that must inevitably follow from any intensive study of color up close,48 circumvent a purely cognitive response to them, activating the corporeal subjectivity of the book's reader (now transformed into an observer or "beholder"), and to this extent are part of that Victorian "reorganization of vision" identified by Jonathan Crary in which "the human body... becomes the active producer of optical experience" (69). In tracing the shifting paradigms for vision in the nineteenth century, Crary has compellingly described how visual experience became "uproot[ed]... from the stable and fixed relations incarnated in the camera obscura" and suddenly granted "an unprecedented mobility and exchangeability, abstracted from any founding site or reference" (14). Certainly Jones's detachment of decoration from the requirement to "represent" contributes to this process too. But given Crary's emphasis on the role of late romantic ideas about color in bringing about this process (67-75), Jones's achievements in the field of color printing may be as important finally as his discovery of the notions of decorative style and form. Jones's contribution to the development of printing, after all, was in adapting a pre-existing process to the mechanical reproduction of color;49 and though Jones had argued in Proposition 14 that "colour is used to assist in the development of form, and to distinguish objects or parts of objects one from another,"50 this proposition is belied by many of the plates in The Grammar, where one can find little formal justification for the bright color arrangements and a corresponding delight in color effects produced simply for their own sake. In its adaptation of the print medium to the requirements of color, and in its pseudoscientific separation of color into its formally constitutive elements (primaries, secondaries, tertiaries, and so forth), The Grammar heralds the arrival of a new scopic regime, in which vision is imagined to be "subjective," rooted in the body and not in the world "out there"; color no longer inheres within a world of objects but "as the primary object of vision, is now atopic, cut off from any spatial referent."51 | ||||||

| Ironically, this interest in the corporeal effects of color had been especially pronounced earlier in Jones's career. It was color that had sparked Jones's interests in historical decoration initially, sending him to Egypt, Sicily, Greece, and eventually to Granada to corroborate his conviction that the architecture of antiquity had originally been colored or painted.52 Color thus seems to have been uppermost in Jones's mind when he visited the Alhambra, in southern Spain, and discovered the magnificent Moorish decorations that would remain his lifelong passion and on which he would ground so much of the theory in The Grammar of Ornament. It was over questions to do with color that Jones became embroiled in the greatest public controversy of his life.53 And it was as England's "most potent apostle of colour" that one obituarist eulogized Jones upon his death, remarking that England had been a land "where colour was as much feared as the small-pox" before Jones's arrival.54 Significantly, then, Jones seems to have overlaid his practical interests in color with a more theoretical and scientific preoccupation with form and reason at some point in the early 1850s. Indeed, one can trace this process in the titles of Jones's lectures in the 1850s, as he turns from defending his controversial color scheme for the Great Exhibition to the business of articulating the general principles all designers should adhere to—a process simultaneous with Jones's absorption within the South Kensington system.55 | ||||||

| "Color is the place where our brain and the universe meet," says Cezanne. "Abstract colour is not an imitation of nature but is nature itself," writes Ruskin: "We deal with colour as with sound,—so far ruling the power of the light, as we rule the power of the air, producing beauty not necessarily imitative, but sufficient in itself, so that, wherever, colour is introduced, ornamentation... may consist in mere spots, or bands, or flamings, or any other condition of arrangement favorable to the colour."56 "Colors are forces, radiant energies that affect us positively or negatively, whether we are aware of it or not," writes Johannes Itten: "The artists in stained glass used color to create a supramundane, mystical atmosphere which would transport the meditations of the worshipper to a spiritual plane."57 Simply through the act of reproducing stained glass, manuscript illuminations, Roman mosaics, and other colored icons,58 by these accounts, Jones harnessed a "radiant energy" of "mystical" power, hardly conducive to the cool rationalism of formalist theory. For this reason, Rhodes may be mistaken in his criticism that "implicit in the very language" of Jones's propositions on color "is a fundamental and traditional suspicion of color as being unruly, potentially disruptive and even aggressive" (220). For though it is certainly true that Jones tempers his advocacy of the primary colors with principled stipulations and qualifications, particularly about the subservience of color to form, the fact remains that Jones's dedication to the spread of polychromatic decoration, and especially his achievement in the field of color printing, was unprecedented. Credit must be given to Jones and later Victorian colorists, such as Rossetti, Morris, and Crane, for helping create a situation from which it is retrospectively possible to see Jones's propositions on color as unnecessarily proscriptive, since it was their achievements in harnessing color to the mass medium of print (and, in Morris's case, textiles) that laid the groundwork for twentieth-century developments in color we now take for granted. Moreover, Jones did not always practice what he preached; and many of the plates to The Grammar show little interest in the subdued hues and compounded tones Jones advocated elsewhere for domestic interiors. One suspects Rhodes attaches too much weight to Jones's propositions, and too little to the plates, in censuring Jones for a "close restriction" of color (324). John Jespersen comes much nearer the mark in saying "It is above all Owen Jones's attitude toward color in The Grammar which distinguishes it from all contemporary publications in ornament" (61) and "in his synthesis of theories of color of the early nineteenth century, Owen Jones created opportunities for a new approach to color in design" (81). | ||||||

| In the completeness with which it embraces the chromolithographic medium, then, The Grammar proves how resistant decoration is to any attempt to legislate its laws. Even today, when electronic publishing makes Jones's plates available "in exquisite clarity" and "in progressively higher resolution," the plates exceed Jones's intentions for them, subverting the traditional relation between illustration and text, because decoration—as distinct from representation—proves wholly resistant to illustration as such. In part, I have been arguing, this excess is a function of the colors harnessed so successfully by Jones. Detached from any representational function, color becomes an inescapably "physiological" entity, writes Crary; "the body itself produces phenomena that have no external correlate" (71). "Wherever colour enters at all...everything must be sacrificed to it," says Ruskin; "when an artist touches colour, it is the same thing as when a poet takes up a musical instrument....all expression, and grouping, and conceiving, and what else goes to constitute design, are of less importance than colour, in a coloured work."59 In part, however, this excess can be traced to the chromolithographic medium. The skill and novelty with which the plates were produced accelerates them beyond Jones's own intentions for them, producing a form of decoration more dizzying and more highly colored than the models on which they are based, and emphasizing precisely those dazzling local and material effects Jones wished to transcend.60 Produced in order to demonstrate the timeless laws of decoration, The Grammar of Ornament ultimately proves how earthbound decoration is and how wholly it operates at the level of substance or medium alone. "The substance of the poem...is the poem itself," writes John Dewey,61 and, by the same token, the substance of decoration is the decorative object itself. "The more art tries to realize itself, the more it hyperrealizes itself," writes Jean Baudrillard, in an axiom that applies well in this case (FS 187). Problematic when viewed in the terms that Jones intended for it, The Grammar embodies what we might call the "ecstasy" of the decorative object62 and it is a testament to decoration's power to evoke that "experience" which aestheticians, from Walter Pater to John Dewey to Arnold Berleant, have traditionally seen as vital to art.63 | ||||||

|

This article was written during my tenure as the Allan C. Clowes Fellow in Fine Arts at the National Humanities Center, Durham, North Carolina, in 2001-02. I thank the Center's donors, staff, and above all, its fellows, especially Mark Parker, Deborah Cohen, Michael Kwass, and John Plotz, for constructive criticism of earlier drafts of this article. 1. Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990), p. 91, hereafter cited in text. 2. Jean Baudrillard, "Fatal Strategies," in Selected Writings, ed. and intro. Mark Poster, tr. Jacques Mourrain (Stanford, 1988), p. 187, hereafter cited as FS. Baudrillard's text is translated rather differently as Fatal Strategies, tr. Philip Beitchman and W. G. J. Niesluchowski (Semiotext(e), 1990), and where I have preferred this translation I have cited it as FS. 3. Contemporary theorists have struggled vainly to distinguish ornament from decoration. See Oleg Grabar, The Mediation of Ornament (Princeton: Bolingen Press, 1992), p. 5 and David Brett, On Decoration (Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 1992), p. 2. But Victorians used these terms fairly interchangeably, and even in the writings of William Morris, whose "On the Origins of Ornamental Art" remains a theoretical milestone on this question, we find as many references to decoration, handicraft, the lesser arts, the "popular" or "everyday" arts as we do to ornament as such. (On this terminological confusion in Morris, see my essay "The Ecology of Decoration.") Towards the end of the nineteenth-century, it is true, one increasingly finds the term decoration replacing ornament as the favored term, as in the following important claim, formulated by Oscar Wilde in 1890:

Nonetheless Wilde will occasionally use the term ornament as freely as decoration, as in his demand for the abolition of "machine-made ornament" (1882) or his call for "good book ornament" (1887) to replace the illustration of books, which in his view had become "too pictorial" and too neglectful of the book's total design. To my mind, then, there is virtually no meaningful difference between these terms as Victorians used them. And if I occasionally alternate between the two in this essay, this is largely because Jones's preferred term "ornament" gets rewritten as "decoration," in the work of disciples and detractors alike, in the later Victorian period. 4. Richard Redgrave, quoted in Nikolaus Pevsner, High Victorian Design (London: Architectural Press, 1951), p. 151. 5. Ibid, p. 151. 6. Ibid, p. 152. 7. John Grant Rhodes "Ornament and Ideology" (PhD Dissertation, Harvard University, 1983), p. 217, hereafter cited in text. 8. See Isabelle Frank, The Theory of Decorative Art (New Haven: Yale University Press for The Bard Center For Studies in the Decorative Arts), pp. 271-75, hereafter cited in text by page number. 9. See Rhodes "Ornament and Ideology," pp. 215 ff. 10. Owen Jones, The Grammar of Ornament (1856; London: Studio Editions, 1986), p. 1, hereafter cited by page number. 11. See the anonymous reviews of Ruskin's The Seven Lamps of Architecture and The Stones of Venice Vol. 1 in Journal of Design and Manufacture, 1 (1849),72, and 6 (1852), 25-28, respectively. 12. Anon. Obituary in Art Journal (1874), p. 211. 13. Lewis F. Day, "Victorian Progress in Applied Design," Art Journal (1887), p. 188, hereafter cited in text by page number. 14. "The Owen Jones Exhibition," The Builder (July 18, 1874), 601. 15. On the South Kensington school, see Brett, On Decoration, pp. 88-90; Alf Boe, From Gothic Revival to Functional Form: A Study in Victorian Theories of Design (Oslo: Oslo U. P., 1957), pp. 66-70, hereafter cited in text by page number; and Rhodes, "Ornament and Ideology," esp. pp. 200ff. For criticism of it, see especially Morris's comment, in "The Lesser Arts," "designing cannot be taught in a school.... The royal road of a set of rules deduced from a sham science of design, that is itself not a science but another set of rules, will lead nowhere" ("The Lesser Arts," in News From Nowhere and Other Writings, ed. Clive Wilmer [Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1993], p. 248). But see n. 14 below. 16. William Morris, "Some Hints on Pattern-Designing," in News From Nowhere and Other Writings, p. 278; William Morris, "Making The Best of It," in The Collected Works of William Morris, ed. and intro. May Morris [London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1914], vol. 22, p. 109. Morris calls the first of these essays "a set of rules or maxims" for the aspiring designer; and though the opening paragraphs of "Making the Best of It" show Morris clearly struggling with the very principle of formulating formal principles ("this kind of rules of a craft may seem to some arbitrary"), both essays come remarkably close to some of Jones's formulations about such questions as the best means of adapting ornament to representation, the important role played by geometry and by structural considerations, the application of color, and the best means of giving relief to the particular parts of an ornamental scheme. The influence of Jones on Morris's imagination is even clearer in Morris's 1890 dialogue "Whigs Astray." 17. Nikolaus Pevsner, Some Architectural Writers of the Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p. 164. See also Pevsner's The Sources of Modern Architecture and Design (1968; New York: Oxford U. P., 1979), p. 10, and his Pioneers of Modern Design, (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1960), pp. 46-49. On the face of it, Pevsner's excavations into the sources of modern architecture and design seem sympathetic to Victorian design principles. But Pevsner selects for praise only those elements — not least, functionalist and formalist elements — consistent with Modernist notions. Essentially, Pevsner viewed High Victorian design as a chamber of horrors within which the spirit of Modernism was born. See especially his book High Victorian Design. 18. Pevsner, Pioneers of Modern Design p. 46; Some Architectural Writers of the Nineteenth Century p. 166. 19. Boe, From Gothic Revival to Functional Form, p. 77. 20. Brett, On Decoration, p. 22. 21. John Kresten Jespersen, "Owen Jones's The Grammar of Ornament of 1856: Field Theory in Victorian Design at the Mid-Century" (PhD Dissertation, Brown University, 1984), p. 1, hereafter cited in text by page number. 22. Charles Handley-Read and Lewis F. Day, quoted in Jespersen, p. 49. 23. E.H. Gombrich, The Sense of Order (2nd ed. Oxford: Phaidon, 1984), p. 51, hereafter cited in text by page number. Where Pevsner and Boe had treated Victorian ideas about decoration within the broader framework of design (as the very titles of their books indicate), largely so as to give accepted Modernist notions a narrative prehistory, Gombrich returns decoration to its Victorian vocabulary — the subtitle of the Sense of Order is "A Study in the Psychology of Decorative Art" — partly so as to call attention to it as an object of study in its own right. 24. See Crary, Techniques of the Observer, p. 2. 25. Ruari McLean writes that Jones "in fact founded a new industry," dating the rise of the chromolithographed illuminated gift-book to Jones's achievements in chromolithography (Victorian Book Design and Colour Printing (2nd. ed London: Faber and Faber, 1972), p. 81. But Jones's achievements have implications that go far beyond literature and the book as such. Jones's career-long involvement with the printing firm De La Rue in producing artistic calendars, playing cards, and other household ephemera gives an important clue to the fitness of Jones's technical achievements to a commodity culture still constrained by the reach of print. 26. Compare, for instance, with Clive Bell, Art (1913; New York: Capricorn Books, 1958): "lines and colours combined in a particular way, certain forms and relations of forms, stir our aesthetic emotions" (p. 17), "forms arranged and combined according to certain unknown and mysterious laws... move us in a particular way, and .. it is the business of the artist so to combine and arrange them that they shall move us" (p. 19), "If the representative element is not to ruin the picture as work of art, it must be fused into the design" (p. 150), "the cognitive or representative element in a work of art can be useful as a means to the perception of formal relations and in no other way" (p. 150) and "We shall have no more architecture in Europe till architects understand that all these tawdry excrescences have got to be simplified away, till they make up their minds to express themselves in the materials of their age — steel, concrete and glass — and to create in these admirable media vast, simple and significant forms" (p. 148). 27. See esp. Alois Riegl's claims in Problems of Style: Foundations for a History of Ornament, tr. E. Kain (Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1992) that "Once plants are used as decorative motifs, the study of ornament finds itself on...solid ground" (p. 7) and that "no matter how divorced from nature a freely invented decorative form may seem, the natural model is always discernible in its individual details" (p. 15). 28. John Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, The Works of John Ruskin, ed. E.T. Cook and A. Wedderburn (London: George Allen, 1903), v. 8, p. 140; Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, Works, v. 9, p. 266. 29. Dresser, who went on to become a considerable theorist of ornament in his own right, drew Plate 8 of Chapter 20 of The Grammar, illustrating what Jones called "the geometrical arrangement of natural flowers." John Jesperson calls this illustration "the most important contribution to The Grammar of Ornament by any architect or scholar" (24). Jesperson notes that Dresser was awarded his honorary PhD from the University of Jena on the basis of this plate. 30. See for instance, Ruskin, "The Work of Iron, in Nature, Art, and Policy," in The Two Paths, Works, v. 16, pp. 375-411. 31. These five propositions also return decoration to the idea of form or inherent structure. Proposition 5 ("Construction should be decorated. Decoration should never be purposely constructed"), for instance—like Proposition 13 on "the unity of the object" decoration is "employed" to serve—is a call to moderate decorative form to considerations of function and purpose. And although Proposition 13 enters the lists in the longstanding debate about whether accurate representation is preferable to stylized or "conventional" forms, on another level it consolidates the idea announced in Proposition 5 that form goes hand in hand with function. The formalist underpinnings of Jones's views on the link between decoration and architecture are perhaps still clearer in Proposition 3 ("Architecture, and all the works of the Decorative Arts, should possess fitness, proportion, harmony, the result of all of which is repose"), in which Jones invokes a familiar neo-Classicism, possibly derived from a reading of Hutcheson's Inquiry Concerning Beauty, Order, Harmony, and Design or Hogarth's An Analysis of Beauty, in order to justify decoration on formalist grounds. But one nonetheless has to turn to Jones's commentary on these Propositions, first delivered as lectures at the Dept. of Practical Art then subsequently published as On the True and the False in the Decorative Arts, for a clear and definitive indication that, for Jones, architecture's value to decorators lay chiefly in the formal and chromatic principles to be gleaned from it: "As architecture is the great parent of all ornamentation, we think it is from the study of architecture alone that we can arrive at those general principles which should govern the employment both of form and colour in the decorative arts." Besides linking decoration with the idea of inherent structure or form, Jones's first five propositions also "monumentalize" decoration in the Victorian imagination, legitimating it as a professional practice akin to architecture, thereby justifying its deployment on a whole range of cultural artifacts. 32. This functionalist ideology may also be latent in Propositions 7, 9, and 11, all of which would subordinate decoration to some larger "design," and perhaps also Proposition 8, with its unconscious echo of the idea (expressed in Proposition 5) of purposeful construction (now characterized as "geometrical construction"). 33. Owen Jones, On The True and The False in The Decorative Arts (London, 863), p. 19, hereafter cited in text. 34. Joan M. Friedman, Color Printing in England 1486-1870 (New Haven: Yale Center For British Art, 1978), p. 53. See also Ruari McLean, Victorian Book Design and Color Printing, pp. 122-24; and "Commentary by Ruari McLean" in "About The Grammar" (pdf. file), pp. 1-5, in Owen Jones's The Grammar of Ornament (cd-rom: Octavo Editions, 1998). 35. The styles illustrated by Jones were each reproduced in ways that emphasize flatness and form over other possible considerations, partly by virtue of the chromolithographic medium itself, and for this reason they are not reproductions at all, in the strict sense, but adaptations of original styles consciously manipulated to suit Jones's purposes. This tendency is especially apparent in Jones's plates showing Roman, Greek, Arabian, and Ninevite ornament, where ornament originally produced in relief, often above eye-level at locations (doorways, entrances) emphasizing human motion, is reproduced flat with virtually no consideration to depth and ground. 36. Quarterly Review, 77 (1845-46), 499. This remark was made about Jones's The Alhambra, but it applies equally well to The Grammar of Ornament. 37. David Pankow, "Chromolithography," in "About The Grammar," p. 7. 38. "Every edition of the work is marred by an occasional carelessly printed page" (Pankow, p. 7). 39. G.A. Audsley, The Art of Chromolithography (NY: Scribners, 1883), p. 10. 40. Rev. of Owen Jones, The Grammar of Ornament, Art Journal (1857), p. 67. 41. Clement Greenberg, Art and Culture (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), p. 133. 42. Jones, On The True and The False, p. 102. 43. Unsigned rev. [G.W. Thornbury], of Jones, The Grammar of Ornament, The Athenaeum, no. 1536 (4 Apr. 1857), 441-42. 44. Introduction to Owen Jones's The Grammar of Ornament 45. Jean Baudrillard, FS, p. 192. 46. Walter Benjamin, "The Work of Art In The Age of Mechanical Reproduction," in his Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, tr. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), pp. 222, 237, hereafter cited in text. 47. The words used by the Art Journal in reviewing The Grammar in 1856 echo those the Atheneum had used, in reviewing Jones's earlier work The Alhambra: "We... can commend the work before us as a nonpareil among illustrative works.... The coloured and gilded fragments of detail, as mere specimens of art, are exquisitely beautiful" (4 Aug. 1838, p. 556). 48. See Crary, Techniques of the Observer, pp. 68-69, 97-98 and 102-7. 49. Senenfelder had discovered lithography in 1798. 50. As Jespersen has shown, this proposition drew Jones into immediate and sharp conflict with Ruskin, who had argued in The Seven Lamps of Architecture that color "never follows form, but is arranged on an entirely separate system" (Works 8:177) and that "the greatest colorists have either melted their outline away, as often Corregio and Rubens; or purposely made their masses of ungainly shape, as Titian" (Works 8: 181 ). See Jespersen, "Owen Jones's The Grammar of Ornament of 1856," pp. 57-61. 51. See Crary, Techniques of the Observer, p. 71. 52. As Michael Darby remarks, "what undoubtedly attracted Jones and Goury to the study of Egyptian buildings was not simply their structure, form and colossal size but the fact that they retained considerable evidence of having been originally covered with paint.... Colour was understandably one of the most compelling aspects of the Eastern experience. To young men brought up in the austere tradition of the white, stuccoed Neo-Classicism of the first decades of the century, the discovery that the prototypes for these designs had originally been coloured, provided an irresistibly tempting opportunity to explore visual phenomena which had been ignored for centuries" ("Owen Jones and The Eastern Ideal," [D. Phil. Dissertation, University of Reading, 1974), pp. 12-14. It was considerations of color and architectural polychromy, then, that drew Jones to the Alhambra in the first place, not those questions of conventionalized form and representation with which Jones would become concerned in the 1850s and with which he would seek to justify "Moresque ornament" in The Grammar of Ornament. 53. See Darby, "Owen Jones and The Eastern ideal," pp. 270-91; also Michael Darby and David Van Zanten, "Owen Jones's Iron Buildings of the 1850s," Architectura, (1974), 54-57. 54. The Builder, v. 32 (1874), 383, 384. 55. See "On The Decorations Proposed for the Exhibition Building in Hyde Park" (1850), "An Attempt to Define the Principles Which Should Regulate the Employment of Colour in the Decorative Arts" (1852), (both in Jones's Lectures On Architecture and The Decorative Arts, printed for private circulation in 1863), An Apology for the Colouring of the Greek court in the Crystal Palace (London: Crystal Palace Library and Bradbury & Evans, 1854), and "On the Leading Principles in the Composition of Ornament of Every Period" (1856), in Lectures On Architecture and The Decorative Arts. 56. Ruskin, Lectures on Architecture and Painting, Works, 12: 94. 57. Johannes Itten, The Elements of Colour (New York: van Nostrand Reinhold), p. 12. 58. See "Medieval Ornament" in Jones, The Grammar of Ornament, plates 66-70. 59. Ruskin, The Stone of Venice, Works 11: 219-20. 60. See McLean's comments on the "brighter" coloring in later editions of The Grammer, in "About The Grammar," p. 4 61. John Dewey, Art As Experience (1934: New York: Perigee Books, 1980) p. 110 62. "Uncertainty, even about fundamentals, drives us to a vertiginous overmultiplication of formal qualities. Hence we move to the form of ecstasy. Ecstasy is that quality specific to each body that spirals in on itself until it has lost all meaning, and thus radiates as pure and empty form" (FS 187). 63. See Walter Pater, Studies in the Renaissance John Dewey, Art As Experience; and Arnold Berleant, Art As Engagement (Philadelphia: Temple U. P., 1991), esp. pp. 9-50. |