The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Kept in the Archives of American Art in Washington, DC, a scrapbook likely assembled in about 1850 by the American painter Miner K. Kellogg (1814–89) and titled “Notices of Powers [sic] Work” is filled with the most fulsome collection of published letters, anecdotes, poems, and other literary tributes (fig. 1) devoted to The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers (1805–73).[1] These documents capture the phase of the Vermont-born sculptor’s greatest renown. Specifically, they detail the public’s effusive outpouring of admiration for the second and third marble versions of The Greek Slave during their North American exhibition tours.[2]

Between August 1847 and December 1849, Powers’s second Greek Slave (1846, Corcoran Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; fig. 2) traveled from New York to Washington, DC; Baltimore; Philadelphia; New Orleans; and Cincinnati. The third version (1847, Newark Museum, Newark, NJ; fig. 3) was first exhibited in Boston; thereafter, in Cincinnati, Louisville, New Orleans, again in Boston, then New York and various small northeastern towns until 1851; subsequently it traveled to Charleston, Nashville, Zanesville and Newark in Ohio, and Indianapolis, before going back to New York in 1853 for display in the Crystal Palace and other exhibitions. (Maps showing the extended journeys of the second version and third version of The Greek Slave through North America are included in Martina Droth’s “Mapping The Greek Slave” in this special issue.) The tours were designed to maximize returns, and, except for Louisville, their routes included the most-populated American cities. Prior to these exhibitions, the first version (Raby Castle, Staindrop), completed in 1844 and purchased by Captain John Grant, had been shown in the summer and fall of 1845 at the London art gallery of the print seller Henry Graves.[3] There it was witnessed by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert and brought Powers instant fame.

Mounted chronologically, the notices from the American tours are organized within the scrapbook according to the routes of the two exhibitions, thereby forming a narrative about the statues’ reception, the climax of which was the “Greek Slave controversy” (fig. 4). Midway through its circuit, the second version of The Greek Slave was seized in Philadelphia by Charles Macalester, an agent of the New Orleans banker and railroad magnate James Robb (1814–81).[4] Robb, who had made a down payment for a Greek Slave in Florence and not received his statue, claimed ownership of the second version while it was displayed in Baltimore. The album culminates in press articles considering the transfer of The Greek Slave to Robb, as well as Kellogg’s published responses in defense of Powers. (For more on Kellogg and his role in the tour of The Greek Slave, see Tanya Pohrt’s article.)

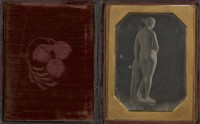

This article considers the origin of the Greek Slave publicity scrapbook, balancing the tour narrative constructed around the Robb controversy with contrasting evidence from other primary sources. As will be explored, conflicts over The Greek Slave’s ownership and artistic merit—one of which resulted in a physical duel—reflected chivalric and sentimental attitudes toward women, as well as the concurrent national crisis over slavery.[5] In spite of The Greek Slave’s impious nakedness, the marble figure’s implied plight at the hands of the Ottomans obliged viewers to adopt a position of compassion and respect for the innocent, yet chained, victim. It is argued that Robb’s aggressive claim and seizure of his statue obliquely mirrored classic tropes of female abduction and rescue, as well as that of the runaway slave. Beyond the statue’s association with abolition among North American viewers, Robb’s opposition to Southern secession is considered within the context of his acquisition. Finally, imagery created in the context of The Greek Slave’s exhibition and included in the scrapbook is illustrated and reexamined, including newspaper caricatures, a daguerreotype, and an oil painting by Kellogg.

Miner K. Kellogg

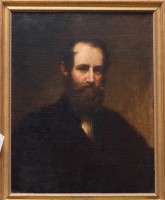

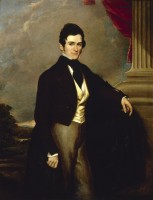

Originally from Manlius, New York, Miner Kellogg first met Hiram Powers in Cincinnati in 1826 (fig. 5). His artistic talent garnered him a scholarship at the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he studied with the artist Robert Walter Weir (1803–89). Connections there helped him to procure an appointment as a courier for the US Department of State, and his subsequent travels were interspersed with time spent painting historic sites in the Middle East. Yet in 1841, Kellogg reconnected with Powers in Florence and rented a studio nearby.

By that time, according to his own accounts, Powers had already conceived of The Greek Slave and planned to exhibit it in America. He wrote to his relative John Richardson on December 14, 1853, that a dream had inspired his work:

When I was a child in Woodstock [Vermont] and for years afterwards in Ohio I was haunted in dreams with a white figure of a woman white as snow from head to foot and standing upon some sort of pedestal below Uncle John’s house. . . . At the time I knew nothing of sculpture. . . . The dream ceased when I began to model—and you know that a white figure of a woman has since been seen in Woodstock [1850, when The Greek Slave was exhibited there] and answering in some respects at least to the vision of my childhood. I know not when I first conceived the idea of the “Greek Slave,” I only know that it was on my mind long before I began it, just as you have seen it—and the dream occurs to me whenever I think of it . . . did the dream cease after I had taken the first steps as an artist because it was no longer necessary to stimulate me on the way I should go?[6]

In addition to this dream imagery, Powers reported to his patron Edwin W. Stoughton in 1869 that he was inspired by accounts of the atrocities committed by the Turks on the Greeks during the Greek War of Independence. He stated:

During the struggle the Turks took many prisoners, male and female, and among the latter were beautiful girls, who were sold in the slave markets of Turkey and Egypt. These were Christian women, and it is not difficult to imagine the distress and even despair of the sufferers while exposed to be sold to the highest bidders. But as there should be a moral in every work of art, I have given to the expression of the Greek Slave what trust there could still be in a Divine Providence for a future state of existence, with utter despair for the present, mingled with somewhat of scorn for all around her.[7]

It is little known, however, that Miner Kellogg reported that Powers’s idea for the statue was inspired by the English painter Seymour Stokes Kirkup (1788–1880), who lived near the sculptor in Florence. A drawing by Kellogg of a young woman who is dressed, but posed similarly to Powers’s marble, is inscribed on the lower register: “from the original sketch by Seymour Kirkup Eq. Painted size of life for Earl Caduggan [sic], Picadilly 1844 and was suggested by Kirkup to Hiram Powers as a subject for a statue, so Kirkup told me in Florence in 1851” (fig. 6). Kellogg repeated this information to newspapers after Powers’s death. While Kirkup was an accomplished artist who had studied at the Royal Academy, Kellogg’s story remains to be proven and the Cadogan oil, located.[8]

During Kellogg’s visit to Italy, the painter offered to take The Greek Slave on tour in America for Powers. Kellogg later asserted that he did so at his own financial risk:

With feelings of the purest friendship I offered to undertake the task for him, and to bear every risk and expense; looking alone to success in the exhibition, for remuneration. This offer was accepted in most grateful language; and in June 1847 I left Florence on this doubtful enterprise. At this time Powers was indebted to me for monies loaned; but I received no written evidence of the fact, nor security of any kind. Added to this I took the whole responsibility of the success of the exhibition of his first statue in America. Without the least security I risked every dollar I then possessed in going to the United States, in pre-paying rent for exhibition rooms, in gas fixtures, furniture, printing, etc. So, that had the statue been lost at sea, or had it failed the secure to [sic] public approbation, I should have been left without the power, or even the probability of obtaining from Mr. Powers compensation for either the monies or the time spent in his service.[9]

These statements are extracted from a defensive pamphlet by Kellogg titled Mr. Miner K. Kellogg to His Friends (Paris, 1858) and stem from a lengthy disagreement with Powers over Kellogg’s compensation as tour manager. This conflict began in 1848, when after the 447 days that the statues were displayed, Kellogg requested payment of $7,068 from the tour’s $24,852.39 in earnings, as agreed in a contract arranged in New York in August 1847.[10] Despite the general success of the American tour and Powers’s payments to Kellogg, the quarrel between the two artists was never fully resolved. The degree to which either party was correct is impossible to discern in retrospect, given that Kellogg himself kept the account books from the tour and may have spent funds that were unrecorded.[11]

Kellogg’s pamphlet provides a clue that he was the creator of “Notices of Powers Work.” A copy of it is mounted into the back of a second scrapbook in the Archives of American Art, titled “Scrap-Book: Catalogue of Library of Miner K. Kellogg” (fig. 7) and devoted to Kellogg’s own publicity notices (fig. 8).[12] In the same manner, a pamphlet by Kellogg titled Justice to Hiram Powers, Addressed to the Citizens of New Orleans is mounted into the center of “Notices of Powers Work” (fig. 9). This document, written and published by Kellogg in December 1848, relates to the Greek Slave controversy. The two pamphlets mirror one another, both in their defensive subject matter, and in being embedded into scrapbooks; the latter fact suggests that Kellogg created both albums. Moreover, handwriting matching Kellogg’s appears in both albums, alongside a second, unidentified hand in “Notices of Powers Work” (figs. 10, 11). Though arranged at least a decade apart, the collective assemblage of clippings in both albums reflects Kellogg’s changing identity and purposes at different points in his career. While “Notices of Powers Work” serves to aggrandize Powers and The Greek Slave, the “Scrap-Book” promotes Kellogg and diminishes Powers through the text of Mr. Miner K. Kellogg to His Friends.

It has been suggested that Powers himself or his daughter Louisa created the “Notices” album, given that it was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution with the contents of his Florence studio in 1968. The above-mentioned evidence suggests otherwise. Even if Kellogg did not construct the album, he nearly certainly culled the newspaper clippings; they are arranged according to his particular route, indicating that he gathered them along the way.

“Notices of Powers Work”

“Notices of Powers Work” bears a marbleized paper cover that opens to a nearly full-page illustration of Powers from an 1873 newspaper obituary, added to the front of the album in retrospect, along with other death notices at the end. Following this portrait, two small New York notices punctuate the center of the next page and serve to draw the reader into the story of the tour as related in the press: “Powers’ celebrated statue of the ‘Greek Slave’ is on exhibition at the rooms of the National Academy of Design. An hour can be well spent examining this great work of art.”[13]

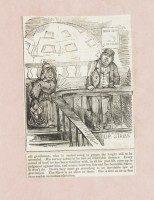

The New York clippings, which continue through page seventy-one, compose the bulk of the album. In keeping with those from other cities, they include stories about Powers’s work on the statue, inspired tracts on art and beauty, numerous poems devoted to the experience of seeing the statue, and various commentaries pertaining to the exhibition, including remarks about the color of the drapery shown behind the statue (fig. 12). On the album’s second page, one learns that The Greek Slave was shown at the New York Society Library, on the corner of Broadway and Leonard Street. There it was placed in the top-floor gallery of the National Academy of Design; the arduous trek up the stairs was caricatured in Yankee Doodle (fig. 13).[14]

The first of hundreds of reverent features about the statue appeared in the New-York Tribune in August 1847: “We do not hesitate to attempt some feeble expression of the delight, the joy, as if at a new revelation of the divine treasures of Beauty, the religious elevation of feeling which seem to flow from the marble like inspirations.”[15] Beyond such obsequious praise, American audiences immediately connected The Greek Slave with the slavery debate. This is evident in Yankee Doodle’s satirical critique, directed at Horace Greeley (1811–72), editor of the Tribune:

The Tribune is in ecstacies [sic] over a Greek Slave about to be exhibited. . . . If the object of Mr. Greeley’s peculiar admiration had happened to be some poor negress from the rice fields of the South, we should no doubt have heard of great doings among the abolitionists, and read some fearful denunciations in the Tribune about the cruelty and hard-heartedness of slave owners. But no sooner is a beautiful Greek slave announced, than Presto!—the sympathy of Mr. Greeley takes another direction, his admiration is excited and we find him perfectly willing that she should be contained in bondage. We ask Mr. Greeley if this is consistent?

We understand that the Greek Slave is pinioned very tight, with no possibility of escaping with her life, and that many rabid abolitionists who have seen her, are loud in their demonstrations of delight; none of them manifesting the remotest desire to free her from present confinement. She seems quite resigned and has never been heard to murmur in the least at her cruel fortune, although she always appears to be on the point of speaking.[16]

The New-York Tribune under Greeley’s leadership was, in fact, a key antislavery mouthpiece during the 1850s, though earlier it did not associate those ideas with The Greek Slave. While direct reports about the abolitionists’ responses are not included in “Notices of Powers Work,” the Yankee Doodle clipping indicates their interest in the statue.

Approximately 150 columns on The Greek Slave appeared in New York papers. Many of these described the origin of the statue, reflected upon its beauty, and commented on the effect of its nudity on audiences. Said one: “We were pleased to find so many ladies present. The man or woman who could entertain an impure thought while looking on this statue, must be grossly sensual indeed. It is the embodiment of woman, consummate in beauty, and innocent as Eve when Adam, walking, first found her by his side.”[17] Another described the scene: “Loud-talking men are hushed into a silence at which they themselves wonder, those who come to speak learnedly and utter extacies [sic] of dilettantism slink into corners where alone they may silently gaze in pleasing penance for their audacity, and groups of women hover together as if to seek protection from the power of their own sex’s beauty.”[18] At the New York Society Library showing in late 1847, the statue was exhibited clothed from nine to ten in the morning for more modest patrons—again to the curiosity of Yankee Doodle, which caricatured this display, showing patrons peering at the draped statue’s ankles with magnifying glasses (fig. 14). By contrast, another column titled “Lascivious Pictures,” appearing in the Christian World of July 1848, censured the exhibit of the third version of The Greek Slave, requesting God-fearing citizens to “frown down all lascivious pictures and all lascivious statuary, whether in the form of a Greek Slave, or a Venus, or Model Artists” (fig. 15).[19] Of course, debate over the statue’s nudity only added to the already-fervent public interest in it.

Following the pages devoted to New York, “Notices of Powers Work” includes clippings from Washington, DC, and Baltimore.[20] From there, the news stories skip to those discussing the third version of the statue in Boston,[21] where in the summer of 1848 it was exhibited simultaneously with the second in Philadelphia before the latter was collected by Robb. Among the Boston clippings appears the only reference in the album to a daguerreotype of the statue. Printed in a Boston column in the Evening Transcript for July 21, 1848, it describes the work of Southworth and Hawes.[22] A daguerreotype in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum has been linked with Southworth and Hawes, though the identity of its creator remains to be firmly established (fig. 16). John Adams Whipple of Boston also took daguerreotype views of The Greek Slave, and a second half-plate daguerreotype (ca. 1850) by Abel Fletcher (1820–90) remains in the collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum.

The concurrent exhibition of two versions of The Greek Slave in Boston and Philadelphia provoked news articles such as “Which is Which?”: “The Philadelphia Inquirer announces that ‘Powers’s Statue of the Greek Slave is now to be seen at the Exhibition of the Academy of Fine Arts in Chestnut-street,’ in that city. Whose Greek Slave is the one we have in Boston?”[23] Another notice similarly detailed the situation:

Greek Slave—Two statues of the Greek Slave by Powers, are now on exhibition: one at Philadelphia, and the other at Boston. A correspondent of the Philadelphia Inquirer says that the one now exhibiting at the “Academy of Fine Arts,” in that city, is the one originally received in this country, which was exhibited in New York last summer, and afterwards at Washington and Baltimore. This statue belongs to a gentleman in New Orleans. The one at Boston was received in this country about two months ago, and is the property of the artist, Mr. Powers.[24]

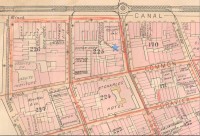

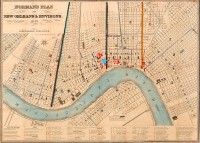

From Boston, Miner Kellogg travelled with the third version to Cincinnati, Louisville, and then to New Orleans (figs. 17–19), where the second was being shown at the painter George Esten Cooke’s National Gallery at 13 Saint Charles Street, together with a Venus created by Lorenzo Bartolini and owned by John Hagan.[25] Founded with the financial support of James Robb and the Alabama industrialist Daniel Pratt, Cooke’s gallery was located on two floors of Pratt’s Saint Charles Street warehouse (figs. 20–21).

James Robb

Of humble origins in Brownsville, Pennsylvania, James Robb endeavored to achieve material success from an early age (fig. 22). He embarked on a prodigious career in banking, advancing quickly and relocating to New Orleans in 1837. There he established the Bank of James Robb, briefly served in the Senate, and was elected president of the New Orleans, Jackson and Great Northern Railroad Company. With his career flourishing, Robb began to organize a sizeable art collection of mainly European works to show at Cooke’s gallery.[26] He also became a noteworthy patron of American artists.

Having remitted three hundred pounds in late 1845 to Powers in Florence as a down payment for The Greek Slave, Robb became impatient over the ongoing exhibition of a statue that had been promised to him.[27] Richard P. Wunder’s detailed account of the correspondence of Powers, Kellogg, and Robb relates the series of events leading to confusion among them; simply put, the second version of The Greek Slave, eventually claimed by Robb, was originally intended for William Ward, 1st Earl of Dudley, who had withdrawn his commission.[28] (Lord Ward’s withdrawal and subsequent commissioning of the fourth version are discussed in Karen Lemmey’s essay “On Discovering the Lost Greek Slave in a Daguerreotype.”) Powers, rather than sending the work to Robb, who effectively owned it, opted to send it on the exhibition tour first. Robb, who may have been influenced by Cooke in his refusal to accept a later version of The Greek Slave, insisted that it was his property and demanded its shipment to New Orleans.[29] To Kellogg and Powers’s chagrin, he offered them no choice other than to dispatch it from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Kellogg and Powers had aimed to send the third statue to Robb rather than halt the exhibition tour, but Robb would not cooperate.

Early on, Powers expressed concerns to Kellogg over Robb’s expectations, writing from Florence in 1847:

I am expecting Mr. Robb’s partner [William Hoge] here . . . I shall get him to write Mr. Robb and state what he thinks of the duplicate Slave; for I intend to send that to Mr. Robb instead of the one you have, for I doubt not that he will be impatient of the delay occasioned by the exhibition, but what shall we do on account of sending it there earlier than you can get there? It ought not to precede you. How would it do to exhibit that in New Orleans? I think Mr. Robb will agree to it, but you ought to be there to show it off. You must write to me your views in your next [letter] and if you can obtain Mr. Robb’s sentiments about it perhaps you might find a trusty person to take charge of the exhibition until you could go to N.O. and set things going there. The [third] statue will be done in a month and the marble is really faultless.[30]

However, Robb’s notion that the statue then on tour was meant for him is suggested in a letter that Kellogg wrote to him from Boston on August 6, 1847, regarding Robb’s commission of a painting titled Circassian Slave.[31]

Kellogg explained to Robb that the painting was on the way, yet also referred to The Greek Slave: “It is my intention to visit New Orleans next winter, and then, if not before, you will receive the ‘Circassian.’ The statue of the Greek Slave will be exhibited in all the principal cities between this and New Orleans where I trust that it will arrive safely at the same time that I do. I shall be very particular not to connect your name with it in any way whatsoever, and then follow out your request in the matter.”[32] This correspondence suggests that Robb perceived the statue on exhibition as slated for him. Kellogg’s promise that the statue would arrive in New Orleans seems to imply that they did privately agree on his claim. Robb’s request for anonymity was designed to prevent the public from falsely believing him to be an investor in the exhibition.

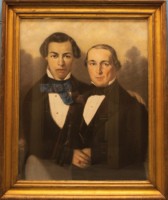

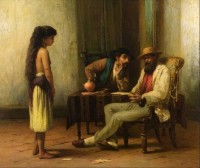

Robb perhaps commissioned Circassian Slave with the intention to display it with the statue that he awaited in New Orleans. The term “Circassian,” meaning “Caucasian,” refers to the people of the northern Caucasus (now Russia), who were known for their striking dark hair and fair skin. That the term “Caucasian” became accepted as a reference to whiteness is owed to the publication of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach’s On the Natural Variety of Mankind (1775), in which the Caucasian countries were posited as the geographic origin of the white race. Like the Greek Slave narrative, the subject of the exotic “Circassian slave” captured the nineteenth-century imagination—especially in the wake of the Russian conquest around 1860, when Circassian women were heavily trafficked into slavery in Constantinople.[33] Paintings and sculpture on the topic abounded, with P. T. Barnum eventually enlisting women to perform the role, a spectacle marketed on cartes-de-visites.[34] Other sculpture akin to The Greek Slave, including the English sculptor John Bell’s marble The Octoroon (1868), similarly fused themes of racial identity and oppression (fig. 23). Images of “white slavery” contributed to an international vogue for the exotic “Orient” (the Middle East, North Africa, and Moorish Spain)—pictures often now defined under the rubric of Orientalism. Many nineteenth-century photographs capture portraits of mixed-race people, especially those who were born in the American South. A substantial subgenre of paintings and sculpture referring to mixed-race marriages and miscegenation stemming from slavery includes paintings produced in New Orleans such as Jules Lion’s Asher Moses Nathan and Son (ca. 1845; fig. 24) and Robert Gavin’s Quadroon Girl (ca. 1870; fig. 25). (Inspired by his observations in New Orleans, Gavin made similar pictures in Tangier, where Quadroon Girl may have been painted.)

Today, only one of Kellogg’s Circassian paintings is documented in the National Academy of Design (ca. 1845; probably from the Suydam collection), though he painted others (figs. 26, 27).[35] As Kellogg reported in the Daily Crescent on March 14, 1849, Robb’s oil painting was purportedly reproduced by “Calamatta of Paris,” likely Luigi Calamatta (1801–69), an engraver and associate of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. (The print is unlocated.)[36] It was exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1855 and offered for auction in New Orleans in 1859 by the firm of Charles Galvani.[37] The painting, which measured thirty-three by twenty-seven and a half inches, is identified in Galvani’s catalogue as having been displayed in Robb’s Washington Street parlor, along with works by notable artists such as Peter Paul Rubens, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, and Daniel Huntington. Robb, having amassed a substantial fortune, had suffered an economic setback, causing him to divest himself of all of his collection. Much of it was acquired by John Burnside, who also purchased Robb’s celebrated Italianate mansion on Washington Street. The rest was scattered among various collectors, and the location of Robb’s Circassian Slave is not known today.

Given the clear association of The Greek Slave (and the Circassian) with the matter of American slavery, Robb’s interest in Powers’s and Kellogg’s artworks raises the question of his own position on slavery and the South’s impending secession. While his papers document some investment in slaves, Robb made no secret of his opposition to secession.[38] In 1863, he printed his 1860 letter to the Honorable Alexander H. Stephens, titled A Southern Confederacy. On the subject of secession, he argued:

It is suicide to the South to surrender the Union; it is the ark of its safety; and to abandon it will commit its future to humiliating changes, and in the end consummate the destruction of Slavery by the process of violence. . . . The Southern mind is deluded in the belief that England and France will give to a separate Southern Confederacy, founded on Slavery, Free Trade and Cotton, their entire sympathies. Where are to be found the evidences of this sympathy? No one can deny that both countries are largely interested in being supplied with Southern cotton; but not anything short of the blindest egotism and ignorance of the sentiment of the people of England and France as to African slavery, can deny that it is almost universally in opposition to it. . . . Cotton furnishes a cheap and convenient clothing for civilized nations but it is not a necessity which they cannot dispense with; the world progressed and was clothed before cotton was planted in Carolina and Georgia.[39]

While Robb’s views on the Confederacy are plain, his own consideration of The Greek Slave and the Circassian Slave in relation to American slavery and its moral consequences is not known beyond the implicit message of those works.

The Greek Slave would have been first received and privately displayed at Robb’s residence at 17 Saint Charles Street, two doors from the National Gallery.[40] It was exhibited at the gallery from November 1848 through March 1849 in order to raise funds to construct an institution named the Asylum for the Relief of Destitute Females.[41] For this exhibition, one of the longest showings of the tour, Robb reprinted Kellogg’s promotional pamphlet titled Powers’ Statue of the Greek Slave, which was offered to gallery visitors.[42] While its introductory paragraphs described the marble as “an emblem of all trial to which humanity is subject,” the irony of its appearance in New Orleans, home to the largest slave market in North America, seems unlikely to have been lost on Robb or his patrons. Prominent newspapers had immediately addressed the idea of the statue’s symbolic relation to American slavery. One author writing in Yankee Doodle wondered “whether [Tribune editor Horace Greeley] ought not in justice to his avowed principles exert all his influence to liberate this slave of Mr. Hiram Powers, as he would have done, had one of Mr. Smith’s favorite mulattoes broken from her master in the South, and been smuggled into New York, on ship-board.”[43] Other columns, including one from the Christian Inquirer, reiterated such sentiments: “A yet deeper moral is there, for Americans, in the leading idea of this statue. It is an impersonation of SLAVERY. This creature, exhibited for sale in the slave market, is a counterpart for thousands of living women. Every day does our own sister city of New Orleans witness similar exposures, with a similar purpose.”[44] Despite the appreciation for The Greek Slave’s symbolic value within northeastern abolitionist circles, unsurprisingly their interpretations did not catch on in the southern press.

The sexual exploitation of African slaves was like that of the Greek and Circassian captives, and such abuse was commonplace and overlooked in the South. It is well known from written and visual accounts that slaves were presented on a plinth or stage for viewing to prospective buyers in the same locales where auctions for dry goods, furnishings, and artworks took place (fig. 28). Often their clothes were pulled away like those of The Greek Slave, so that they could be examined in a prurient fashion.[45] A map prepared by the Historic New Orleans Collection in conjunction with the 2015 exhibition Purchased Lives: New Orleans and the Domestic Slave Trade, 1808–1865 shows that within blocks of Cooke’s National Gallery there existed fifty-two discrete sites where the sale of men, women, and children took place on a large scale between 1811 and 1862 (fig. 29).[46] An unnamed source cited by Wunder explains that Robb’s exhibition was unsuccessful despite the printing of handbills and “an enormous red flag across the street.”[47] Oversized red flags were often displayed outside American slave markets, as Maurie McInnis has discussed in Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade.[48] Such a flag appears in Eyre Crowe’s painting of a Richmond slave market. Given that the National Gallery was located in a small area infested with slave-auction sites, it is plausible that the flag signified the presence of one or more, but its purpose in the context of Wunder’s quotation is not clear.

Cooke’s early demise during a cholera epidemic in 1849, together with Robb’s financial difficulties, contributed to the permanent closure of the National Gallery in March of that year.[49] An editorial column, perhaps written by Kellogg, appeared in the Daily Delta in February 1849. Its author castigated the local citizenry for the $2,000 in earnings brought in by the National Gallery for the women’s asylum, explaining that this took much-needed funds from the sculptor himself.[50] This report of earnings is unproven; however, it indicates that the exhibit entertained about four thousand people, since admission was fifty cents. Despite Robb’s exhibition, an indignant Kellogg had proceeded with his plan to exhibit the third Greek Slave along with Powers’s Fisher Boy, Prosperine, and General Andrew Jackson (a bust-length portrait) at the State House on Canal Street in New Orleans (figs. 30, 31). Their exhibitions overlapped for less than one month between late February and March of 1849.[51]

Neither exhibition was well attended by comparison to the crowds in other cities, probably due to the cholera. The ten-week show at the State House brought in only $729.55, less revenue than the two-week exhibition at Louisville directly prior, and less than half of the National Gallery earnings.[52] Following the National Gallery’s closure and amid a temporary downturn in his fortunes, Robb sold the statue to the Western Art Union in Cincinnati. There it was offered by lottery, won by James d’Arcy of New Orleans, and subsequently sold to William Wilson Corcoran in February 1851 for $3,500. It remained in the collection of the Corcoran Gallery of Art until 2015, when that museum closed, and it was moved to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

Controversy

While in Cincinnati with the third statue, which had been sent from Florence as a replacement for Robb’s marble, Kellogg had begun to cull the first published references to James Robb, including a Daily Dispatch write-up titled “Mr. Robb and the Greek Slave” (fig. 32). Dated November 15, 1848, the article consisted of a letter by Kellogg to the newspaper editors, implicating Robb as “threatening and insulting” in his claim on the statue.[53] Learning of the debacle surrounding the famous marble, journalists began to address the Greek Slave controversy, increasing the public’s fervent interest in the statues. Two excerpts marked “Nonpareil,” among the Cincinnati notices, describe this phenomenon:

The “Slave Case” excitement has only tended to an increase of visitors to her prison-house—Instead of robb-ing the sculptor of his dues, it has added new strength to the “powers that be.” Go every body and see the Slave.

The desire to see the Greek Slave increases each day, and the number of visitors has been more than double since the stir about Mr. Robb’s boasted liberality as a patron of the arts. From all that we can learn from the most reliable sources, we are satisfied that he would make a big name at the expense of the hard earned fame of our own gifted Powers. More anon.[54]

While likely pleased with this attention, Kellogg and Powers became concerned for Powers’s reputation with the public, as Robb’s own statements reached the newspapers. In advance of his visit to New Orleans, Kellogg printed the pamphlet Justice to Hiram Powers, Addressed to the Citizens of New Orleans, which included sections of correspondence arranged to suggest Robb’s recalcitrance. He later published a denser conglomeration of letters as Vindication of Hiram Powers in the “Greek Slave” Controversy.[55]

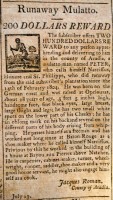

The majority of the letters reprinted in Kellogg’s defensive tracts had already been submitted to newspapers, thereby spinning off debates of their own. Journalists took creative liberties, likening Robb’s claim of his property to kidnapping or outright theft from Powers. For example, on January 19, 1851, John Moncure Daniel, editor of the Richmond Weekly Examiner, reported that the sculptor was “Robbed of his treasure. The proprietor ravished away the lady, and shut her up in his house. . . . The finale is that the beautiful bone of contention is lost to the public.”[56] As Peter Bridges has shown, Daniel quarreled with Edward W. Johnston, editor of the Richmond Whig, over the merits of The Greek Slave. That debate, coupled with their general political differences, reached the point of a duel between the two men in Bladensburg, Maryland, though neither was injured.[57] While illegal in some places, dueling remained de rigueur for dealing with matters of propriety until after the Civil War. The statue’s qualities, like the honor of a flesh-and-blood woman, were ultimately defended in the duel, indicating that The Greek Slave had the propensity not only to inspire passion, but also to reflect contemporary social mores pertaining to “respectable” women. Further, the same newspapers that covered Robb’s controversy also included lengthy descriptive notices for runaway slaves, whose disappearances could be costly for their owners (fig. 33). Robb’s seizure of his “slave” property in Philadelphia and its transfer to New Orleans where “she” was displayed amidst the slave markets is curiously parallel to the retrieval of a plantation runaway. The dual role of The Greek Slave as virtuous lady and degraded servant further highlights the breach between Southern chivalry and slavery, ironically enacted in the Daniel-Johnston duel.

Whatever Powers’s original intent, The Greek Slave remains the best-known antislavery statement of the nineteenth century. “Notices of Powers Work,” likely assembled by Kellogg, carefully documents first-hand accounts of what made the statue a success in America—its skilled execution and pulchritude, and the national spectacle over Robb’s contested ownership. Generally, its visual appeal drew in viewers who would otherwise dismiss its antislavery message, a point not lost on the abolitionist community. In Cincinnati, Kellogg pasted into his book a short article titled “Unparalleled Outrage” in the Cist’s Advertiser of November 1, 1848: “She is a slave, on her way to the South—the slave-holding South! Where are our Abolitionists? Are the sympathies of Chase, and Mitchell and Birney exhausted in their past efforts? Why do they not obtain a writ of habeas corpus in the case?”[58] The reference is to Salmon P. Chase (1808–73), William M. Mitchell (1826–79), and James G. Birney (1792–1857), all opponents of slavery.

In recent years, scholarly research has addressed the nineteenth-century display of The Greek Slave, with meticulous attention given to the fabric backdrop, accompanying objects, and other aspects of presentation. While these details may differ, what remains consistent is that the statue is not known to have been displayed specifically as a monument to the abolitionist cause. The Greek Slave was recognized by contemporaries for its relationship to the American slavery debate, yet such critical interpretations by journalists and the broader public were mitigated by its sensational nudity and speedy dispatch to private collections and museums. By contrast, other historic American sculpture that is permanently installed outdoors continues to function more pointedly as a symbol of municipal opinion and collective memory. In New Orleans, where The Greek Slave was once briefly shown amidst slave-trading sites, the bronze statues of Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Pierre Toutant-Beauregard, and Confederate president Jefferson Davis, have long remained as outdoor monuments. However, in early 2016, public outcry over their import as objects venerating the Confederacy has caused those artworks to be scheduled for eventual removal.[59]

[1] “Notices of Powers Work,” 1847–1849, 1873–1876, Hiram Powers Papers, box 14 (hol), folder 1, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (henceforth AAA), http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/container/viewer/Scrapbook-Notices-of-Powers-Work--284830. While it is generally devoted to the Greek Slave tour, the album ends with some of Powers’s obituary notices from 1876. In 1968, Powers’s heirs divested his Florence studio of its remaining contents; objects and documents were given to the Smithsonian Institution. The American art historian William Gerdts supervised the transfer of objects and archival materials, including the book of clippings, from Villa Powers. The Archive of American Art’s expert reproductions of the scrapbook have enabled me to reproduce details of specific pages, which illuminate my focus around The Greek Slave and slavery. For fully legible images of the scrapbook, please refer to the link and specific frame numbers cited in the endnotes and in the relevant captions.

[2] Comprehensive exhibition schedules of all of Powers’s six versions of The Greek Slave are given in Martina Droth’s essay and digital interactive “Mapping The Greek Slave.” Based on research undertaken for this special issue, the interactive augments and updates the earlier exhibition schedules published in Richard P. Wunder, Hiram Powers: Vermont Sculptor, 1805–1873 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1991), 2:157–77. Powers’s celebrated statues were the first in history for which such tours were arranged.

[3] Grant later sold the sculpture, and it was bought in 1859 by Henry Vane, 2nd Duke of Cleveland, for his home at Raby Castle, Staindrop, England, where it remains.

[4] For a brief biography, see “The Son of a Poor Widow, How He Rose from Poverty to Affluence,” New York Times, August 2, 1881, accessed June 7, 2016, http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=990DE6DA133EE433A25751C0A96E9C94609FD7CF.

[5] Other scholarship has addressed The Greek Slave’s contradictory meanings (such as powerlessness as opposed to spiritual triumph), its relationship to abolition and slavery in America, its connection with power relations within American marriage, the manner in which it was displayed, and its early photographic reproductions. See Joy S. Kasson, “Narratives of the Female Body, The Greek Slave,” in Marble Queens and Captives: Women in Nineteenth-Century American Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 46–72; Wendy Jean Katz, “Hiram Powers and Dueling Codes of Honor,” in Regionalism and Reform: Art and Class Formation in Antebellum Cincinnati (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2002), 137–71; Maurie D. McInnis, “Exhibiting the Slave Trade in England,” in Slaves Waiting for Sale: Abolitionist Art and the American Slave Trade (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 173–213; Martina Droth, Jason Edwards, and Michael Hatt, eds., Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901 exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 246–51, 308–27; Lauren Lessing, “Ties that Bind: Hiram Powers’s Greek Slave and Nineteenth-Century Marriage,” American Art 24, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 40–65; Vivien M. Green, “Hiram Powers’s Greek Slave: Emblem of Freedom,” American Art Journal 14, no. 4 (Autumn 1982): 31–39; and Charles Colbert, “Spiritual Currents and Manifest Destiny in the Art of Hiram Powers,” Art Bulletin 82, no. 3 (September 2000): 535.

[6] Hiram Powers to John Richardson, December 14, 1853, Hiram Powers Papers, box 8, folder 40, frame 26, AAA, http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/container/viewer/Richardson-John-P--284620.

[7] Hiram Powers to Edwin W. Stoughton, 1869; cited in Linda Hyman, “The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers: High Art as Popular Culture,” Art Journal 35, no. 3 (Spring 1976): 216.

[8] Cadogan was presumably George Cadogan, 3rd Earl of Cadogan, whose collection was sold by Christie’s after his death in 1865.

[9] Mr. Miner K. Kellogg to His Friends (Paris, 1858), in “Scrap-Book: Catalogue of Library of Miner K. Kellogg,” Miner Kilbourne Kellogg Papers, AAA. See also Miner Kilbourne Kellogg Papers, microfilm D30 and D33. Other scrapbooks and journals compiled by Kellogg are described in the online resource “Archives Directory for the History of Collecting in America,” The Frick Collection, accessed June 7, 2016, http://research.frick.org/directoryweb/browserecord2.php?-action=browse&-recid=7367 - Miner.

[10] Wunder, Hiram Powers, 2:242.

[11] Ibid., 2:207–65.

[12] Below the title of this scrapbook is the following notation: “Lent to Mr. Wm. J. Reese for examination.” Rather than the library catalogue mentioned in the title, this album contains a spread of clippings gathered from different cities and pertaining to Kellogg’s own work, the earliest of which date to the late 1840s.

[13] Unknown publication, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 3, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334569.jpg.

[14] “Hiram Powers’ Greek Slave,” Yankee Doodle, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 23, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334589.jpg.

[15] “City Items,” New York Tribune, August 24, 1847, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 4, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334570.jpg.

[16] “Greek Slave,” Yankee Doodle, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 5, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334571.jpg.

[17] “Powers’ Statue of ‘The Greek Slave,” The Age, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 5, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334571.jpg.

[18] Unknown publication, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 19, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334585.jpg.

[19] “Lascivious Pictures,” Christian World, July 1, 1848, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 91, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334657.jpg.

[20] “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 72, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334638.jpg; frame 76, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334642.jpg.

[21] “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 83, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334649.jpg.

[22] “The Greek Slave—Daguerreotype Views,” Evening Transcript, July 21, 1848, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 101, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334667.jpg. The album contains only a few Philadelphia notices.

[23] “Which is Which?” Evening Transcript, July 20, 1848, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 100, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334666.jpg. This report erroneously states that the statue was shown in New Orleans prior to its arrival in Philadelphia.

[24] Unknown publication, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 100, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334666.jpg.

[25] “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 124, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334690.jpg; frame 201, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334767.jpg; “Galvani’s record of paintings in Louisiana, 1855–1890,” AAA. The Groves scrapbook, previously owned by Dr. I. M. Cline, was given to the archives by William E. Groves. It belonged to New Orleans art dealer Charles Galvani in the 1840s and ’50s, and later to the collector and publisher Armand Hawkins.

[26] See Catalogue of the Collection of Paintings and Other Works of Art Belonging to James Robb, Esq., Washington Avenue, New Orleans (New Orleans: Picayune Office Print, 1859), The James Robb Collection, MSS 265, Williams Research Center, The Historic New Orleans Collection (henceforth THNOC).

[27] For a full account of Robb’s Greek Slave commission, see Wunder, Hiram Powers, 2:217–33.

[28] Ibid., 2:217–35.

[29] Ibid., 2:230.

[30] Ibid., 2:228n90.

[31] Kellogg to James Robb, August 6, 1847, Miner Kilbourne Kellogg Papers, reel D33, AAA.

[32] Ibid.

[33] See Linda Frost, “The Circassian Beauty and the Circassian Slave: Gender, Imperialism, and American Popular Entertainment,” in Never One Nation: Freaks, Savages, and Whiteness in US Popular Culture, 1850–1877 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005).

[34] Gregory Fried, “A Freakish Whiteness: The Circassian Lady and the Caucasian Fantasy,” Mirror of Race (March 15, 2013), accessed June 10, 2016, http://mirrorofrace.org/circassian/.

[35] David Dearinger, “Miner Kilbourne Kellogg,” in Painting and Sculpture in the Collection of The National Academy of Design (New York: Hudson Hills, 2004), 330–31.

[36] “The Greek Slave, at the State House,” New Orleans Daily Crescent, March 14, 1849, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 206, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334772.jpg; Gary Tinterow, Philip Conisbee, and Hans Naef, Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999), 312–13.

[37] Catalogue of the Thirty-Second Annual Exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (Philadelphia: T. K. and P. G. Collins, 1859), 15, cat. no. 232; Catalogue of the Collection of Paintings and Other Works of Art Belonging to James Robb, Esq.

[38] The United States Census (Slave Schedule) of 1850 identifies Robb as owning at least one slave. See the record for James Robb, New Orleans, Louisiana, United States, “United States Census (Slave Schedule), 1850,” FamilySearch, accessed 3 June 2016, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MVZN-9XQ; citing line no. 7, NARA microfilm publication M432 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 443,488. The author thanks Mary Lou Eichorn of THNOC for her help in locating this citation.

[39] James Robb, A Southern Confederacy: Letter by Jas. Robb, Late a Citizen of New Orleans to Hon. Alexander H. Stephens, of Georgia (Chicago: J. S. Thompson, 1863), The James Robb Collection, MSS 265, THNOC.

[40] New Orleans Annual and Commercial Register of 1846 (New Orleans: E. A. Michel, 1845), 495, accessed June 7, 2016, https://archive.org/details/neworleansannual00mich. No photographs of this house are known to exist. It was purchased in 1851 by the Orleans Club and was later occupied by the Carl Krost Brewery. The Greek Slave was never kept at Robb’s palatial Washington Street residence, as has been surmised. Today, Saint Charles Street is officially designated Saint Charles Avenue.

[41] “The Greek Slave Controversy. The Destitute Supporting the Destitute,” Daily Delta, February 28, 1849, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 203, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334769.jpg.

[42] Powers’ Statue of the Greek Slave (New Orleans: Norman, 1848).

[43] “The Greek Slave,” Yankee Doodle, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 5, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334571.jpg.

[44] Christian Inquirer, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 36, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334602.jpg.

[45] McInnis, “Dressed for Sale,” in Slaves Waiting for Sale, 115–44.

[46] This exhibition took place at THNOC from March 17 to July 18, 2015.

[47] Wunder, Hiram Powers, 2:237.

[48] See McInnis, “The Red Flag,” in Slaves Waiting for Sale, 85–114.

[49] For a biography of Cooke, see Kevin E. O’Donnell, “‘The Artist in the Garden’: George Cooke and the Ideology of Fine Arts Painting in Antebellum Georgia,” Crossroads: A Southern Annual (2004): 73–97.

[50] “The Greek Slave,” Daily Delta, February 28, 1849, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 203, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334769.jpg.

[51] For examples of these works see Andrew Jackson, 1834–35, carved 1839, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (94.14); Fisher Boy, 1841–44, carved 1857, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (94.9.1); and Prosperine, 1839–73, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC (1926.11.1).

[52] “In all it had grossed only $729.55, which was $1300.70 less than the receipts had been in Louisville for a two-week showing as opposed to ten in New Orleans.” Wunder, Hiram Powers, 2:239.

[53] “Mr. Robb and the Greek Slave,” Daily Dispatch, November 15, 1848, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 139, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334705.jpg.

[54] Unknown publication, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frame 140, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334706.jpg.

[55] Vindication of Hiram Powers in the “Greek Slave” Controversy (Cincinnati: Printed at the Office of the Great West, 1849).

[56] Peter Bridges, Pen of Fire: John Moncure Daniel (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2012), 46. The January 19, 1859, issue of the Richmond Weekly Examiner, from which Bridges took this key quotation, is presently missing from the Library of Congress. Therefore the outline of the Daniel-Johnston debate is not known.

[57] Bridges, Pen of Fire, 46–48.

[58] “Unparalleled Outrage,” Cist’s Advertiser, November 1, 1848, in “Notices of Powers Work,” frames 127–28, http://www.aaa.si.edu/assets/images/collectionsonline/powehira/fullsize/AAA_powehira_1334693.jpg.

[59] Ramon Antonio Vargas, “Last Legal Barrier to Removing Confederate Monuments Overcome as Judge Shoots Down Preservationists’ Request,” New Orleans Advocate, January 26, 2016, accessed June 3, 2016, http://theadvocate.com/news/neworleans/neworleansnews/14689095-84/last-hurdle-to-removing-confederate-monuments-judge-shoots-down-preservationists-request-mitch-landr.