The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

The bonds between Modernist sculpture, the New Sculpture and the Arts and Crafts Movement . . . helped critics and the public to understand the products and claims of avant-garde sculptors before the First World War.

—S. K. Tillyard[1]

Chronologies of Sculpture “on or about” 1890 to 1914[2]

In 1987, the writer and historian Stella Tillyard proffered an argument in her book The Impact of Modernism that went against the grain of most conceptualizations of British sculpture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Her proposition that there were strong bonds and interconnections between sculpture that has conventionally been separated into the neat, but inadequate, categories of the “Victorian” and the “Modern” has, however, only recently gained stronger currency.[3] Drawing on Tillyard’s path-breaking, but under-acknowledged, observations about how the critical vocabulary developed for sculpture in the late nineteenth century prepared the way for the reception of the sculptural experiments in the early twentieth century, this essay will argue for a more flexible narrative for sculpture, which rather than separating objects and critical writings made before 1900 from those made in the twentieth century, brings them together. Sculpture’s modernity was Janus-faced, constantly looking backward and forward and, likewise, our conception of the period needs to look both ways if we are to make sense of the complex networks of the profession, practice, display, and reception of sculpture in this period. The results of such chronological crisscrossing—moving between before 1900 and after 1900—can produce some dizzying and potentially unsettling effects. However, the benefit of such an approach is that it allows us to create a more complex narrative for the notoriously messy production of sculpture, rather than attempting to organize it too neatly under headings of the “Victorians” and the “Moderns.” Returning to the writings about sculpture at the turn of the century, I want to suggest that it is a particularly effective medium through which to reaffirm the very real bonds which connected artistic practices in the decades on either side of 1900.

By revivifying the connections between what Tillyard described as Modernist sculpture, the New Sculpture, and the Arts and Crafts Movement, we potentially unsettle 1900 from its comfortable position as a starting point for histories of Modernism (as recently seen in the large collection Art Since 1900).[4] As Tillyard suggests, this bringing together of sculpture and the debates surrounding it from either side of the nineteenth/twentieth century divide is not “so much to suggest a new ‘line of influence,’” as to “encourage a more generous and catholic approach to the upheaval in British art in the four years before the First World War.”[5] It is crucial not to erase differences or homogenize responses, which might be an unwelcome side effect of looking for connections and continuities, or to situate nineteenth-century artists as proto-Modernists. Instead, I want to propose that we think about a transitional, or interstitial, period for sculpture in the decades on either side of 1900, when ideas about the role of sculpture were rapidly changing. By returning to the written discussions about sculpture before and after 1900, the connections between the Arts and Crafts Movement and Modernism start to come into sharper view.

Despite some significant exceptions, the divide between “Victorian” and “Modern” seems to have tenaciously retained its grip on conceptualizations of sculpture from this period. Why is this so? One reason I want to suggest is that the texts about sculpture which have endured and which are most used by art historians are those with a manifesto-like quality which emphasize change, difference, and innovation, rather than continuity, connection, and overlap. Edmund Gosse (1849–1928) and Ezra Pound (1885–1928) both strategically included the term “new” in their critical writings about sculpture; Gosse in his four-part series of articles “The New Sculpture,” published in the Art Journal in 1894, and Ezra Pound’s manifesto of the same title, published in the Egoist in 1914.[6] This repetitive use of the phrase “the new sculpture” was surely more than mere coincidence.[7] Gosse’s and Pound’s texts have been used frequently by art historians of both Victorian sculpture and of the early twentieth-century avant-garde to validate the newness and radicalism of “their” period. However, by taking another look at both sculpted objects and the range of writing about sculpture from the period, we can detect that there were many shared concerns between nineteenth- and twentieth-century sculpture which were recognized at the time. A complete break from the sculptural past was more of a rhetorical strategy, particularly on Pound’s part, than accurate description of the sculptural landscape in Britain at the turn of the century.

Writing About Sculpture in Britain Before and After 1900

The fact that there exists no book upon present or recent sculpture in Great Britain—nothing beyond occasional articles in the magazines—has prompted the production of this volume.[8]

Most writers are not beyond making a claim for the originality of their work, and we might readily interpret M. H. Spielmann’s (1858–1948) assertion in the preface to his book British Sculpture and Sculptors of To-Day (1901; fig. 1) as engaging in a bit of promotional hype. However, an examination of the bibliography will quickly verify Spielmann’s statement. In the years around 1900, books dedicated to sculpture, and contemporary sculpture in particular, were scarce, bearing out sculpture’s continued marginal status relative to painting well into the twentieth century. When it did appear, critical commentary on sculpture was largely confined to art magazines and the periodical press in the form of exhibition reviews, or to the announcement of the unveiling of public statuary in national and local newspapers. As a result, historians have generally confined themselves to the relatively small selection of articles from this period that discuss sculpture at any great length, and these have been mined from the opening word to the final full-stop by those researching the critical vocabularies of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century sculpture. However, as the material in the 2014 exhibition catalogue Sculpture Victorious makes clear, there is a large and hitherto relatively under-used archive of press articles and images from illustrated magazines, as well as institutional and private records, relating to sculpture in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Authoritative books or comprehensive survey texts on the subject were, as Spielmann suggests, scarce. However, those who actively engaged with formulating a critical discussion dedicated to sculpture at the end of the nineteenth century formed a fairly small coterie of art writers and critics; these included, as well as Spielmann, Edmund Gosse, Cosmo Monkhouse (all three of whom are discussed in further detail by other contributors to this special issue), Alfred Baldry, Walter Armstrong, and Claude Phillips. As Martina Droth has observed, the theoretical writing about sculpture in this period was “authored by a small group of critics, artists and collectors, many of them closely connected with each other through friendships and neighbourhoods.”[9] To understand the critical discourse on sculpture at this time, we need to think about these networks and webs of relations, both professional and personal, which connected sculptors and critics.

In the years bridging 1900, the sentiment that British sculpture was more appreciated on the Continent than in Britain was one that was frequently expressed in published texts. As A. C. R. Carter lamented in the Art Journal issue of May 1897, “If sculpture has not its votaries in this country to the extent of appreciative admirers abroad, it is not for the want of distinguished and gifted exponents.”[10] However, if sculpture’s votaries remained relatively few in number, they were, nonetheless, often forceful and influential voices within cultural debates in turn-of-the-century Britain. Spielmann’s assessment of British sculpture in 1901 was ambitious and upbeat. There had been nothing short of a renaissance, he argued, for British sculpture since “1875 or thereabouts,” employing the powerful rhetoric of change and difference so often enlisted in these manifesto-like texts. A “radical change has come over British sculpture,” he argued. It was “a change so revolutionary that it has given a new direction to the aims and ambitions of the artist and raised the British school to height unhoped for, or at least wholly unexpected thirty years ago.”[11] To support this rousing assessment, Spielmann drew on the words of a painter: the, by then, august Sir John Everett Millais. In a passage which was first reproduced in the Magazine of Art, Millais states:

So fine is some of the work our modern sculptors have given to us, that I firmly believe that were it dug up from under the oyster shells in Rome or out of Athenian sands, with the cachet of partial dismemberment about it, all Europe would straightway fall into ecstasy, and give forth the plaintive wail “We can do nothing like that now!”[12]

Through the creation of an imagined classical heritage for British sculpture, Millais aimed to allay anxieties about what the rest of Europe thought about British sculpture. This was an anxiety that often accompanied even the most celebratory assessments of the state of British sculpture at this time. For Spielmann, the regeneration for British sculpture “came from without,” citing the influences of French sculptors: Carpeaux, to whom “the inspiration of the new trend was originally due,” and especially Jules Dalou and Eduard Lantéri, both of whom had a significant impact on sculptural pedagogy in Britain through their associations with the National Art Training Schools and the South Kensington School of Art.[13] Writing in an article published in the Magazine of Art in June 1901, John Hamer observed a shift in this relationship. The article was devoted to the sculptor Albert Toft, described as one of “our rising artists.”[14] Hamer opened the article with his assessment of the change in fortune for sculpture in Britain, positioning it in relation, once again, to France:

English sculpture of twenty years ago had little importance for the foreign critic, if indeed it existed for him at all; and if now we are beginning to hold our own in this great art among the nations of Europe, we may justly give credit for this to a small body of workers, among whom may be included Mr. Albert Toft. France has a greater number of sculptors than ourselves, but the best English work is not in quality below that of the Continent; and it is pleasant to know that at length such work is freely recognised and admired abroad.

This critical positioning of British sculpture amidst the larger currents of the European sculptural world permeated much of the critical discussions about sculpture in this period.

Even if writings on sculpture from this period amounted to a select body of literature, what is perhaps more significant are the outlets in which the most theoretically sophisticated texts were published. Magazines and journals of art such as the Magazine of Art (1878–1904), the Art Journal (1839–1912) and the Studio (from 1893) were of crucial importance to the formulation and dissemination of critical texts about sculpture, even if Spielmann did rather dismissively characterize them as “occasional articles in the Magazines.” Edmund Gosse’s articles on “The New Sculpture” were published in the Art Journal. Sculptors in this period were also closely allied to certain journals. George Frampton (1860–1928), for example, regularly contributed to the Studio. And it was in these “occasional” articles, such as those by Gosse and Baldry, that new critical languages, which were specific to the material experiments of late nineteenth-century sculpture, were developed. As David Getsy has observed, Gosse’s articles on “The New Sculpture,” along with his series “The Place of Sculpture in Daily Life,” published just a year later, “remained the central retrospective and synthetic look at British sculpture until the publication of Marion H. Spielmann’s British Sculpture and Sculptors of To-Day in 1901.”[15] It was then another six years before Ernest Short’s History of Modern Sculpture, but half of this book was devoted to Greek and Roman sculpture.[16] It would not be until 1921, with the publication of Kineton Parkes’s two-volume Sculpture of To-day that another comprehensive study of sculpture would appear.[17] Therefore, in the period under review here, the bulk of sculptural criticism was published in article form; a format that encouraged shorter, perhaps more provocative, pieces which addressed the contemporary moment and often batted away even the recent past with pithy dismissals. It was largely a literature which was written by those who often knew the sculptors they were writing about personally. Inserted in between articles on painting, decorative art, and architecture, the inter-meshed nature of writing about sculpture both within personal networks and within the wider landscape of periodical arts criticism should not be underestimated when reviewing the literature before and after 1900.

In a collection about art writing ca. 1900, we have to consider this supposed paucity of published critical discussion about sculpture in Britain head on. Tillyard is rather blunt in her assessment of the scarcity of critical literature on British sculpture around the time of Spielmann’s survey: “Sculpture was a subject neither for extensive debate nor for frequent controversy.”[18] She goes on to say that it was only “with the emergence of Modernism and the debate it engendered that a corpus of critical material was formed.”[19] As I have discussed above, there were indeed very few books devoted to British sculpture. However, I would argue that there was a ground shift in the perception of sculpture and its place in the modern world long before “the emergence of Modernism.” Evidence for it may have to be gleaned from exhibition reviews, “occasional” articles in magazines and newspapers, journalistic reports of the unveiling of statues and tombs, writings by sculptors (both published and unpublished), business records and institutional archives, and the often dry and descriptive texts of the exhibition catalogue. Clearly, there is still much work to be done in stitching together the fragments of sculpture’s histories between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The visual illustration and reproduction of sculpture is also crucial for understanding the critical debate surrounding it. Take, for example, an article in the popular weekly publication, the Illustrated London News entitled “The Largest Piece of Sculpture Ever Cast in England” which was published on October 3, 1903 (fig. 2).[20] This was G. F. Watts’s (1817–1904) Physical Energy, made at Parlanti’s foundry in West Kensington, London, which the title of the article explains was an “unfinished work” (Watts would continue to work on the sculpture until his death in 1902). Drawings by one of the Illustrated London News artists, Hugh Fischer, as well as the accompanying text, focus on the technical and visually dramatic aspects of the bronze casting technique. The drama of the unveiling of the finished product (in this case destined for the grave of Cecil Rhodes in the Matapo Hills of Zimbabwe, then Rhodesia)—that moment in the lives of public monuments which was most conventionally represented in drawings and photographs of public statuary—is replaced with scenes of the sculpture’s manufacture. Ropes, pulleys, wooden supports, plaster, and molten bronze are the main subjects here. Underneath the pictures of the bronze casting in action was a description of how the bronze cast was made using the lost-wax method. Similar depictions of process had also occurred in the Illustrated London News in relation to early monuments; for example, the Wellington Monument in the 1840s.[21] For the Illustrated London News to devote whole pages to the documentation and illustration of the skilled labor of the making of these monuments indicates that there was significant public interest in sculptural production. This kind of visibility for sculpture and its manufacture, in the illustrated press and in books filled with photographic reproduction, began to steadily increase as the twentieth century progressed and reproductive illustration became cheaper. However, visualizing the process of making the sculpted object had its roots in the sculptural renaissance of the nineteenth century.

Bridging the Divide: Arts and Crafts/ Modern Sculpture

In British Sculpture and Sculptors of To-day, Spielmann included figures we might not necessarily expect to find in a book about “sculptors of to-day.” Walter Crane (1845–1915), for example, was widely regarded as a craftsman and designer[22] rather than as a sculptor, yet Spielmann saw fit to include him in his survey. Using the ceremonial mace that Crane had designed in 1889 for the Corporation of Manchester (fig. 3), Spielmann included Crane in his survey as “pioneer” of the new breed of sculptor “decorators” who had injected sculpture in Britain with a “fine decorative quality.”[23] It was, Spielmann wrote, the “‘liney’ character of his designs,” rather than the “sculpturesque” quality which characterized Crane’s “brilliant work.”[24] Crane would concur, in his own writing, with this assessment about the “liney” quality of his sculptural work, explaining that “the great point to bear in mind in all design—the sense of relation; nothing stands alone in art. Lines and forms must harmonise with other forms and lines; the elements of any design must meet in friendly cooperation.”[25] This spirit of cooperation informed not only concepts of design in this period, but also wider critical discussions about the art object and the artist/art worker. Tillyard observes that it was through the “co-option” of artists such as Crane and objects such as the Manchester mace that “the borders of sculpture as a fine art were expanded.”[26] The effects of such co-option, she argues, were that given “the right setting, any object could become a sculpture.”[27] This opening up of the borders of sculpture had a profound impact on the next generation of sculptors in the twentieth century. Tillyard uses Jacob Epstein’s (1880–1959) Rock Drill as an example, arguing that such precedents meant that this work “could be more easily accepted as sculpture and his transformation of utilitarian objects into an essential part of the sculpture did not force critics or the public to make an impossible adjustment to their definition of the art.”[28] An increasingly expanded field of sculptural objects was produced by sculptors, designers, and craftsmen and craftswomen associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement, and included objects such as metal dishes, ceremonial objects, copper photograph frames (William Reynolds-Stephens (1862–1943) exhibited one at the 1888 Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society), doorknockers, and statues for the home. Such an expanded conceptualization of the boundaries of sculpture had an effect which reached beyond the experiments of Epstein, Eric Gill (1882–1940), and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891–1915) in the early twentieth century.

While recent revisionist histories have paid sustained attention to the artists dubbed by Gosse as the “New Sculptors,” such as Frederic Leighton (1830–96) and Hamo Thornycroft (1850–1925), there is still a paucity of critical discussion about those practitioners who were more closely allied to the Arts and Crafts Movement.[29] George Frampton is one such artist whose career and practice offer an interesting case study for thinking about the Janus-face of sculptural modernity between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Born in London in 1860, Frampton followed in the footsteps of his stonemason father. Frampton decided to go into the sculpture business, learning his trade first as a mason in Paris on the scaffolding of the Hôtel de Ville. Returning to Britain, he trained with William S. Frith at the South London Technical Art School from 1880 to 1881 and then taking up a place at the Royal Academy Schools in 1881, where he would study until 1887. Although often discussed as a “Victorian” sculptor, he was active well into the twentieth century and held positions of prominence in the art world into the 1920s. For example, he was the first British sculptor to exhibit at the Venice Biennale in 1897 and became President of the Royal Society of Sculptors in 1911.[30] His work crosses all kinds of categories, and he was known at the time both for his association with other “New Sculptors’ and for his active involvement with the Art Workers” Guild and the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society. Frampton was an experimental sculptor who used a wide range of materials in making his objects, including wax, a variety of metals, gemstones, plaster, and stone. Aymer Vallance, in 1899, wrote:

The art of Mr. George Frampton, A.R.A., may perhaps best be described as composite sculpture; that is to say, that he seldom confines himself in any given work to one single medium, but draws upon many materials—e.g. bronze and various kinds of marbles; stones, such as lapis lazuli; mother-of-pearl and other shells: amber and ivory, to obtain the effect desired. Yet even these do not suffice for some of his finer pieces, which are further enriched with enamelling, gold and silver.[31]

Frampton’s sculpture of Dame Alice Owen (1897; fig. 4), described by art historian Catherine Roach as a “triumphant example of mixed-media sculpture,” was made from marble, alabaster and bronze, and also included paint and gilding.[32] This material experimentation certainly predates the more regularly championed experimental approach to materials and materiality by twentieth-century sculptors. Frampton’s extensive activities, experimental practice, and chronology-crossing career from the Victorian period into twentieth century are, of course, not unique, and here I am using his example as a case study taken from a wider circle of Arts and Crafts practitioners who sculpted, including Alfred Gilbert, William Reynolds-Stephens, Mary Seton Watts (1849–1938), and Feodora Gleichen (1861–1922).

The Arts and Crafts Movement also created professional networks and physical spaces in which “Victorian” and “Modern” sculpture overlapped.[33] The Art Workers Guild was one such interstitial space which, I suggest, has been undervalued in discussions of turn-of-the-century sculpture. Founded in 1884, its early membership comprised fifty-six artists, including twenty-six painters, fifteen architects, four sculptors, and eleven other kinds of craftsmen and women.[34] From these figures, it would seem that sculpture and sculptors played a marginal role in a society whose purpose it was to unite the arts and crafts. However, if the activities of the society are considered more closely, it becomes apparent that sculptors did play an important role in the life of the guild. In the first twenty-five years of the guild’s existence, sculptors held the position of Master. The first chairman was the sculptor George Blackall Simonds, followed by Edward Onslow Ford and George Frampton. Hamo Thornycroft was a member from 1884–1901, as was Alfred Gilbert (member from 1900–1903; re-joined in 1932). The subjects discussed at the first two meetings, on June 10 and July 4, 1884, were sculpture topics: “Processes of Modelling” and “Sculpture, from the different Craftsmen’s points of view”; subsequent meetings continued to pay attention to aspects of sculptural practice.[35]

This second topic is of great significance to the debates that I am charting here. It shows that sculpture, for the members of the Guild at least, was something in formation, that it was open and debatable from different perspectives. The Guild was also a place in which materials greatly mattered and where the ethical and spiritual dimensions of materiality, labor, and craft were frequently debated.[36] The concept of work and being an “art worker” also united the various members. George Frampton elected to designate himself as such, as Fred Miller explained in his article “George Frampton, A.R.A., Art Worker” in the Art Journal of November 1897.[37] “George Frampton is an all-round craftsman,” he wrote, “and prefers to be known as an art worker, and not by the more restricted title of sculptor, though it was his originality and skill in this direction which gained him the Associateship of the Royal Academy in 1894.”[38] Frampton was presented in the article as a forward-looking innovator who criticized “the slavish following of old forms, so much insisted upon in some art schools,” which “becomes harmful because of its stifling the utterance and paralyzing the movements of those just beginning to find themselves.”[39] Miller highlighted Frampton’s interaction with the materials and tools of sculpture, noting that “what a craftsman can and may teach is hand cunning, finger dexterity, ‘tricks of the tools’ true play’ . . . A teacher in Art must be a craftsman, and the more all-round worker he is the more helpful and sympathetic a teacher he is likely to be, and it will also enable him to select fit and worthy craftsmen to help him.”[40] This notion of craftsmanship, a dexterity and understanding of the tools and trade of making sculpture, would be reinforced in the “truth to materials” ethos for sculpture promoted by Gill, Gaudier, and, further on in the twentieth century, by the likes of Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth. Frampton was, Miller summarized, a “master of many methods, . . . truly an art worker, and he esteems it an honour to belong to the Art Workers’ Guild and the Arts and Crafts Society. This pigeon-holing of people, which compels them to devote all their energies to one small section of work, is one of the outcomes of the factory system.”[41]

This critique of labor and the “factory system” of production, heavily inspired by the debates of the Art Workers Guild and the writings of the sixth master of the guild in 1892, William Morris, flowered well into the twentieth century in relation to sculptural practice and discourse. This was explicitly expressed in the work of Eric Gill, a stonemason and letter-cutter, who joined the Art Workers Guild in 1909. Like Frampton, Gill’s training and associations had strong Arts and Crafts links. In 1900, he entered the offices of the architect and Guild member W. D. Caröe. During his apprenticeship, he also attended evening classes in monumental masonry at the Westminster Technical Institute and attended lettering classes with the pioneering calligrapher Edward Johnston at the Central School of Arts and Crafts (which was set up by W. R. Lethaby in collaboration with Frampton).[42] Like Frampton, Gill would regularly insist on being called a worker: “The artist . . . is the skilled workman. His business is to make what is wanted for those that want it.”[43] Describing the carving of his first sculpture, Estin Thalassa, he wrote:

Without knowing it I was making a little revolution. I was reuniting what should have never been separated: the artist as man of imagination and the artist as workman. . . . I was completely ignorant of all their art stuff and was childishly doing my utmost to copy accurately in stone what I saw in my head.[44]

This concept of the sculptor’s craft which Gill proffered is not that far removed from the critic A. L. Baldry’s conceptualization of the way in which the sculptor Reynolds-Stephens worked. Writing in the Studio in 1899, Baldry described Reynolds-Stephens as belonging to a network of artists who

hold strongly the creed that the true mission of the art worker is to prove himself capable of making many things, to show that he has an all-round knowledge of the varieties of technical expression, and a practical acquaintance with many methods of stating the ideas which are in his mind.[45]

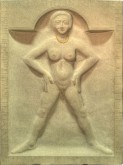

Estin Thalassa was to be the first of many reliefs that Gill would carve during his career. The sculpted relief is central to the “web of relations” before and after 1900 that I have attempted to tease out in this essay. The sculpted memorial plaque was bread and butter work for both Frampton and Gill, but they also used this format as a vehicle for experiment, as did others, such as Alfred Gilbert, Jacob Epstein, and Gaudier-Brzeska. Frampton and Gill shared a particular interest in lettering, both designing distinctive letter forms which they regularly incorporated into their sculptural work, as seen in Frampton’s Memorial to E.V. Neale in St. Paul’s Cathedral (1892–93; fig. 5) and Gill’s A Roland for an Oliver/ Joie de Vivre (1910; fig. 6). In both examples, the carved lettering (in marble relief in Frampton’s memorial, and cut into the stone in Gill’s piece), are not relegated to merely conveying fact, but are an intrinsic part of the design. The social and aesthetic value of lettering was something which Arts and Crafts designers had become particularly attentive to, and it was an area which Gill continued to develop in his practice until his death in 1948. It was an aspect of Gill’s talent as a sculptor and stonecutter that Roger Fry would alight on in his review of Gill’s first solo show, at the Chenil Gallery in 1911:

Mr Gill, then, is a stone-cutter—in all that belongs to the technique of stone-cutting he is an expert, and the exquisite quality and finish of his surfaces bear witness to this no less than the perfection of those incised inscriptions for which he has long been celebrated. Indeed, his long apprenticeship in a purely abstract and formal art, that of handwriting and letter-cutting, seems to have given him all the assurance, the judgment of eye, and the certainty of hand, which are supposed to be cultivated only by the incessant practice of the studio.[46]

These reliefs remind us that sculptors in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, “Victorian” and “Modern,” were still very much embedded within the memorialization business. However, they saw the memorial not simply as an object shackled to the conventions of memorialization, or the plaque as something which had to blend unobtrusively into its surroundings. As the Art Journal commented of the Royal Academy exhibition of 1898 at which Frampton showed his memorial to the shipbuilder Charles Mitchell, which was sited in St George’s Church, Jesmond, Newcastle:

Mr George Frampton, who always shows evidence of striking out new paths for himself, sends a bronze memorial, which well illustrates the possibilities of sympathetic meaning and decorative expression open to the originally-minded sculptor anxious to treat his art as an effective adjunct to architecture.[47]

The accolade of “striking out new paths” for oneself is something usually reserved in art history for the avant-garde artists of the twentieth century, not the Royal Academician and sculptor of commemorative plaques. Revived by the sculptors connected to the Arts and Crafts Movement, the sculpted relief became a testing ground for sculptural experimentation at the end of the nineteenth century. It offered the possibility to test out interesting compositions and designs, often with the inclusion of an inscription, combined with the attraction of being a steady income stream for sculptors into the twentieth century. The relief, often incorporated into the wall of a church or other building to serve as a memorial, is an inherently public art. This was something which Gill exploited when he submitted two reliefs, Crucifixion and A Roland for an Oliver to the Chenil Gallery exhibition. Contemporary reviews commented on the “expressive” mode of Gill’s carving of the male and female naked human form. For Frank Rutter, writing in the Sunday Times, these were powerful and public sculptural statements. “Whatever Mr Gill may think about these matters, we, who have seen his reliefs, know, unless we are hopeless dullards, that he feels about them strongly, deeply, even savagely.”[48]

Materials Matter

The Victorian period has often been characterized as an age of bronze, whereas Modernist sculpture has been written about primarily in relation to stone. However, looking again at turn-of-the-century sculpture, we can see that, in practice, such material divisions are difficult to maintain. Frampton, as we have already seen, frequently worked with mixed media, most famously in his gilded and painted bronze, marble, and alabaster memorial to Dame Alice Owen. While Gill, Epstein, and Gaudier-Brzeska have become known for their adherence to directly carving in stone, they also used bronze and other materials. Gaudier-Brzeska, for example, frequently experimented with plaster, as seen in Bird Swallowing a Fish and the Wrestler (both originally carved in plaster). The casting/carving divide makes very little sense when we consider the eclectic range of materials and techniques which sculptors employed on either side of 1900. Connections in design, form, and subject matter also can be readily found. A comparison between Frampton’s Mysteriarch (1896; fig. 7) and Epstein’s bust of Mrs Ambrose McEvoy (1909–10; fig. 8) suggests powerful interrelations. Using another of Epstein’s bronze sculptures, the head of Romilly John (1907; fig. 9), Evelyn Silber has stressed the distance of Epstein’s work from his Victorian predecessors (if we can indeed call them that—many were, after all, still working at this time). She writes that the “smooth cap is a critique on the fussily decorative, pseudo-historical headdress . . . favoured by Victorian sculptors, such as Sir Alfred Gilbert (1854–1934), Alfred Drury (1856–1944), and Sir George Frampton (1860–1928).” She argues that Epstein “strips away this decorative irrelevance . . . while at the same time exploiting the inherent qualities of bronze, without recourse to the ivory and semi-precious stones favoured by Frampton.”[49] Yet, only two years later, Epstein made a bronze bust which did not “strip away” the decorative, but made it central to the work. In both Frampton’s and Epstein’s busts, the elaborate necklaces which hang around the necks of their somnambulant female sitters, are central features in the composition. This interest in jewelry and medals was not unique to “Victorian” sculptors such as Alfred Gilbert and Frampton, both of whom were talented metalworkers, but is again something which features in the work of the supposed “direct carvers” of the twentieth century. Gill regularly incorporated jewelry into his sculpture, as seen in A Roland for an Oliver, in which the woman wears carved beads which have been highlighted with yellow paint. Gaudier-Brzeska also made small objects with holes pierced in them so that they could be worn on a piece of string around the neck of the people who purchased them. However, this engagement with “fussy,” “decorative” objects such as jewelry has been written out of the histories of sculptural Modernism and, yet, it was this eclecticism and diversity of practice that characterized and connected sculpture, and the writing about it, in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries. As Christopher Reed has written:

When we think of modern art, however, we do not generally think of domestic imagery or objects for the home, for in the arts the linkage of domesticity and modernism has been obscured by another conceptual invention of the nineteenth-century: the idea of the “avant-garde.”[50]

Many factors have contributed to the suppression or eradication of what Jessica Feldman has described in her work as the “web of relations” between the Victorian and the Modern.[51] The bonds which Tillyard persuasively mapped for sculptural discourse and practice have all too often been severed, and there has often been an assumption that the Modernists cleared away the “decorative” to create a smooth, plain, and neat-edged tabula rasa on which to build the foundations of a “new” kind of art practice in the twentieth century. Yet, historians of sculpture are beginning to reconnect sculptural practices and vocabularies across the supposed divide of “1900.” As Penelope Curtis has observed:

In recent years, students of “Modern British Sculpture” have become more aware of its roots in the late nineteenth century and, more particularly, of how the fin de siècle foreshadows modernism’s interests in the arrangement and reception of sculpture.[52]

The exhibition, Modern British Sculpture, which opened at the Royal Academy in January 2011, and which was co-curated by Penelope Curtis and Keith Wilson, staged these connections and precedents in one of the exhibition’s rooms which contained sculpture from 1877 to 1863 by Frederic Leighton, Alfred Gilbert, Charles Wheeler (1892–1974), and Philip King (1934–). As Martina Droth argued in her essay on this grouping, such an arrangement of objects “questions the notion that formal ‘developments,’ ‘transitions’ or becoming ‘modern’ can be traced chronologically through sculptural idioms and forms, opening up different ways of thinking about old and new.”[53] As well as exhibitions, digital resources such as the Mapping the Profession and Practice of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851–1951 database, run by the University of Glasgow, have made a wealth of information on the infrastructures and networks of the business of making sculpture—a kind of information often buried deep within archives—freely available online.[54] This opening up has the potential to have profound effects, not only for thinking about the interconnected history of sculptural practice and its critical vocabularies on either side of 1900, but also for larger art-historical questions about the limitations of linear chronologies and over-zealous periodization.

I would very much like to thank Martina Droth and Peter Trippi for giving me the opportunity to write about the art writing on sculpture in this collection of essays. They have generously offered guidance and advice throughout the process, as has Robert Alvin Adler. My ideas presented here have also been shaped by conversations over the years since completing my Masters degree in Sculpture Studies at the University of Leeds and the Henry Moore Institute. I would like to thank Penelope Curtis, Jon Wood, Martina Droth, David Getsy, Morna O’Neill, Michael Hatt, Jason Edwards, and Mark Antliff for sharing their ideas about sculpture “on or about” 1890 to 1910, and for also listening to my thoughts on the topic.

[1] S. K. Tillyard, The Impact of Modernism: The Visual Arts in Edwardian England (London: Routledge, 1988), 158.

[2] I am borrowing the “on or about” from Virginia Woolf’s phrase “on or about December 1910 human character changed.” Virginia Woolf, Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown (London: The Hogarth Press, 1924), 5.

[3] See, for example, the conclusion of David J. Getsy, Body Doubles: Sculpture in Britain, 1877–1905 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004), 181–87.

[4] Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, and Benjamin Buchloh, eds., Art Since 1900 (London: Thames and Hudson, 2005).

[5] Tillyard, Impact of Modernism, xvi.

[6] Edmund Gosse, “The New Sculpture: 1879–1894,” Art Journal, May 1894, 138–42; Edmund Gosse, “The New Sculpture: 1879–1894,” Art Journal, July 1894, 199–203; Edmund Gosse, “The New Sculpture: 1879–1894,” Art Journal, September 1894, 277–82; Edmund Gosse, “The New Sculpture: 1879–1894,” Art Journal, October 1894, 306–11; and Ezra Pound, “The New Sculpture,” Egoist, February 16, 1914, 67–68.

[7] For a more in-depth discussion of the “new sculpture” in relation to Ezra Pound, Sarah Victoria Turner, “Ezra Pound’s New Order of Artists: ‘The New Sculpture’ and the Critical Formation of a Sculptural Avant-Garde in Early Twentieth-Century Britain,” Sculpture Journal 21, no. 2 (2012), 9–22. This article had its origins as a paper given at a conference at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds held on February 17–18, 2011, entitled “The New British Sculpture: Reviewing the Persistence of an Idea.”

[8] M. H. Spielmann, British Sculpture and Sculptors of To-Day (London: Cassell, 1901), n.p.

[9] Martina Droth, “Sculpture and Aesthetic Intent in the Late-Victorian Interior,” in Rethinking the Interior, c. 1867–1896, ed. Jason Edwards and Imogen Hart (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2012), 218–19.

[10] A. C. R. Carter, “The Royal Academy, 1897,” Art Journal, May 1897, 181.

[11] Spielmann, British Sculpture, 1.

[12] John Everett Millais, quoted ibid.

[13] Spielmann, British Sculpture, 1.

[14] John Hamer, “Our Rising Artists: Mr. Albert Toft,” Magazine of Art, no. 25 (June 1901): 393.

[15] Getsy, Body Doubles, 8.

[16] Ernest Short, A History of Modern Sculpture (London: Heinemann, 1907).

[17] Kineton Parkes, Sculpture of Today, 2 vols. (London: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1921).

[18] Tillyard, Impact of Modernism, 143.

[19] Ibid.

[20] “The Largest Piece of Sculpture Ever Cast in England,” Illustrated London News, October 3, 1903, 499.

[21] See “The Great Wellington Statue,” Illustrated London News, July 11, 1846, 21 and “The Statue at Mr. Wyatt’s Foundry,” Illustrated London News, October 3, 1846, 213.

[22] P. G. Konody, The Art of Walter Crane (London: George Bell & Sons, 1902).

[23] Spielmann, British Sculpture, 157.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Walter Crane, Line and Form (London: George Bell & Sons, 1900).

[26] Tillyard, Impact of Modernism, 150.

[27] Ibid., 150.

[28] Ibid., 151.

[29] An exception is the work of historian of sculpture, Benedict Read. Read has done much to research the histories of these Arts and Crafts-connected sculptors. See in particular his pioneering Victorian Sculpture (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1984).

[30] Tancred Borenius, “Frampton, Sir George James (1860–1928),” rev. Andrew Jezzard, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004); online ed., October 2007, accessed May 1, 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/33242. See also Andrew Jezzard, “‘An All-round Craftsman’: George Frampton’s Church Monuments,” Journal of the Church Monuments Society 11 (1996): 61–70.

[31] Aymer Vallance, “British Decorative Art in 1899 and the Arts and Crafts Exhibition. Part I,” Studio, 18 (1899): 52–54.

[32] Catherine Roach, “George Frampton (1860—1928),” in Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of invention, 1837—1901, ed. Martina Droth, Jason Edwards, and Michael Hatt (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014), 373.

[33] Martina Droth, “The Ethics of Making: Craft and English Sculptural Aesthetics c. 1851–1900,” Journal of Design History 17, no. 3 (2004), 221–36.

[34] H. J. L. J. Massé, The Art-Workers’ Guild 1884–1934 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1935), 14.

[35] Ibid., 102.

[36] For a list of subjects discussed at the guild from 1884 to 1934, see ibid., 102–32.

[37] Fred Miller, “George Frampton, A.R.A, Art Worker,” Art Journal, November 1897, 321.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid., 322.

[40] Ibid., 323.

[41] Ibid., 324.

[42] Judith Collins, Eric Gill: The Sculpture, A Catalogue Raisonné (London: Overlook Books, 1998), 12.

[43] Eric Gill, Art and a Changing Civilisation (London: John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1934), 111.

[44] Eric Gill, Autobiography (London: Jonathan Cape, 1940), 249.

[45] A. L. Baldry, “The Work of W. Reynolds-Stephens,” Studio 17 (1899): 74–84.

[46] Roger Fry, “An English Sculptor,” Nation, January 28, 1911, 718–19, reprinted in Christopher Reed, ed., A Roger Fry Reader (Chicago and London: Chicago University Press, 1996), 134.

[47] A. C. R. Carter, “The Royal Academy, 1898,” Art Journal, June 1898, 184.

[48] Frank Rutter, “The Art Galleries,” Sunday Times, February 5, 1911, 6.

[49] Evelyn Silber, The Sculpture of Epstein (Oxford: Phaidon, 1986), 15.

[50] Christopher Reed, introduction to Not at Home: The Suppressions of Domesticity in Modern Art and Architecture (London: Thames & Hudson, 1996), 7.

[51] Jessica Feldman, “Modernism’s Victorian Bric-a-brac,” Modernism/Modernity 8, no. 3 (2001), 453.

[52] Penelope Curtis, “How Direct Carving Stole the Idea of Modern British Sculpture,” in Sculpture and the Pursuit of a Modern Ideal in Britain, c. 1880–1930, ed. David J. Getsy (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004), 291.

[53] Martina Droth, “Authority Figures,” in Modern British Sculpture, ed. Penelope Curtis and Keith Wilson (London: Royal Academy, 2011), 114.

[54] Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851–1951, University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII, online database 2011, last accessed March 27 2015, http://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/. This project was initiated and directed by the art historian Ann Compton who, as a Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art Senior Fellow, is working on a project entitled A Collective Art: The Makers and Methods of Sculpture in Britain c.1851–1940 which promises to cross chronological and conceptual divides in the history of British sculpture.