The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Dedicated to Patricia Mainardi—Inspiring Mentor, Beloved Friend

Paul Gauguin’s first fresco, now known as Breton Girl Spinning (fig. 1), was completed in the fall of 1889. This untitled work was rendered in oil on plaster on the west wall of the dining room of a small auberge called Buvette de la Plage in Le Pouldu, an isolated hamlet on the Breton coast where Gauguin (1848–1903) stayed for one year with his friend and follower Meijer de Haan (1852–95).[1] The meaning and the title for this painting have been the subject of unresolved debate. This article will explore the history of this mural to offer insight into the ways in which changes of social and cultural context may have affected the fresco’s interpretation through time.[2]

Breton Girl Spinning was one part of room decorations by Gauguin and de Haan that were completed over the course of a few weeks in the fall of 1889 (probably in late October or early November). Despite their swift execution, the decorations were elaborate, extending onto all four walls of the inn’s dining room, including parts of the doors and one window.[3] Gauguin’s and de Haan’s works were soon augmented by those of other artists, including Paul Sérusier and Charles Filiger, who also came to the small inn.[4] By the time the decor was complete, the ornamentation of the dining room encompassed paintings of every major type—genre, landscape, self-portraiture, portraiture, still life, and even history painting—in media ranging from tempera and oil on plaster to oil on canvas and panel; as well as prints and drawings; painted and glazed ceramic vessels; exotic found objects; and carved, polychromed figures in wood.[5] Even the ceiling was painted by Gauguin with stylized images of geese, onions, and a punning inscription.[6]

The spontaneous—even hurried—way the decorations expanded to encompass all of the room’s surfaces save the floor, and the multiple hands that participated in the project, together make the determination of a distinct iconographic program, if one ever actually existed, difficult to discern; so too does the eclectic nature of the decorations. Images of abundance and fecundity—harvest scenes, a nursing mother and child, and still-lifes with ripe fruit, onions, and poultry—were joined with paintings, prints, and sculptures engaged with portrayals of desire, want, temptation, playfulness, piety, and punishment—including exotic nudes, phallic forms, villagers dancing, the Virgin Mary, and Adam and Eve in paradise and being expelled from Eden. There is no scholarly consensus regarding the meaning of the room’s decor. Was the dining room filled programmatically, or haphazardly, with fecund and fallow metaphors for the cycle of life? And if these apparent themes were planned deliberately, were they stimulated by Meijer de Haan’s growing amorous relationship with the inn’s young proprietress, Marie Jeanne Henry (popularly known as “Marie Poupée” for her doll-like beauty), and by Paul Gauguin’s self-pity over mounting personal difficulties?[7] Or was it a site abounding with Christian allegories, inspired, perhaps, by Gauguin’s recent re-encounter with Breton Catholicism after his stay with Vincent van Gogh in Arles, by his friendship with the fellow painter and devout Catholic Emile Bernard, or by his exposure to the teachings of a charismatic Catholic prelate Mgr. Dupanloup during his formative years in school in Orléans?[8] Or was the room simply a rich but inchoate center for artistic improvisation and self-expression? Each of these possibilities will be examined below.

Further complicating a secure interpretation of the room’s décor was the complete displacement of most of the paintings, prints, and sculptures from the inn in 1893. That year, Marie Jeanne Henry retired from innkeeping, leased her auberge, and moved to live with her new companion Henri Mothéré.[9] All of the decorations that could be readily detached from the inn’s walls were taken by Henry to decorate her new home with Mothéré in Kerfany.[10] Only the ceiling painting and three frescos on the west wall of the dining room—the spinner by the sea (under consideration here), a large harvest scene by de Haan (the mural that inaugurated the room’s decoration), and a small painting of a goose by Gauguin on a transom above the door—remained in situ after Henry left Le Pouldu with her two daughters.[11]

Sometime after Henry leased her inn (possibly not until she sold it in 1911), the murals remaining at the auberge were covered over.[12] They remained publicly unknown until Gauguin’s and de Haan’s frescos were rediscovered in May 1924 at the Restaurant de la Poste et de la Plage, as Henry’s former inn was now called. The murals were found under many layers of wallpaper, when the current owner of the Restaurant, Mme Cochennec, was redecorating her establishment.[13] Cochennec subsequently sold the still-untitled frescos in 1925.[14] Gauguin’s mural of a Breton girl in a coastal landscape remained in private hands until 2006, when the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam acquired the painting.[15] Gauguin’s fresco was placed on public display two years later with the title it now bears: Breton Girl Spinning.

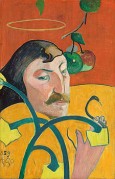

Since its discovery in the early 20th century, the fresco’s many different titles have included Joan of Arc (Jeanne d’Arc)[16] and A Peasant Spinning by the Sea, her Dog and her Cow (Une paysanne en train de filer sur le bord de la mer, son chien et sa vache).[17] Variants of the latter title, including the one employed by the Van Gogh Museum, accord with the artist’s sole known contemporary account of the painting given in a letter sent from Le Pouldu to Vincent van Gogh in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.[18] Written in the fall or early winter of 1889 (possibly on or around December 13), one year after the tumultuous end of the artists’ sojourn together in Arles, Gauguin’s correspondence opens with an apology for his belated response to Van Gogh’s last letter, attributing his delay in writing to his complete absorption in a joint effort with de Haan in decorating the dining room of the inn where the two artists were staying.[19] He continues with a brief description of the frescos that inaugurated their collaborative project, beginning with de Haan’s mural, now known as Breton Women Scutching Flax:Labor (Les Teilleuses de lin: Labor),[20] and followed by his own contributions to the inn: Breton Girl Spinning (fig. 1), Self-Portrait, and Portrait of Meijer de Haan with a Lamp:

Ages ago, I should have replied to your long letter; . . . yet many circumstances have prevented me from doing so. Among others a rather large job which De Haan and I have undertaken together: a decoration for the inn where we eat.— Beginning with one wall, then ending by doing all four, even the leaded-glass window. It’s something that teaches you a lot, and so it’s useful. De Haan has done a large panel on the actual plaster, 2 meters by 1.50 high . . .—Peasant women from around here working with hemp against a background of ricks of straw. I consider it very good and very complete, as serious as a painting — I did a peasant spinning at the sea’s edge, her dog and her cow, after that— our two portraits on each door.— In the fever of work and the haste to see it all finished, the time for bed arrived suddenly and I postponed my letter.[21]

The titles Peasant Spinning by the Sea,Breton Girl Spinning, or The Spinner clearly accord with the artist’s own description of this painting. So why has the wholly different title—Joan of Arc or Jeanne d’Arc—lingered in the literature surrounding this fresco? (Among the many scholars who have employed this title or subtitle are Georges Wildenstein, John Rewald, Vojtěch Jirat-Wasiutyński, Ziva Amishai-Maisels, Françoise Cachin, Debora Silverman, and Victor Merlhès).[22] The alternative name might seem inappropriate but for the presence of an angel bearing a sword descending from the heavens in a golden cloud at the top left of the composition. The appearance of this remarkable celestial being with mauve wings, a bottle-green gown, and long red hair is striking, and its vivid presence makes it impossible for the viewer to regard the image as a simple peasant genre scene, as the artist characterized it. This strongly symbolic element disrupts the artist’s own “straight” interpretation of this composition, and opens up a variety of possible meanings, including that the spinner might be Eve being expelled from the Garden, or that she might be Joan of Arc (ca. 1412–31), the young peasant who claimed to be called to deliver France from the English during the Hundred Years War by the voice of Saint Michael, and later by the voices of Saints Catherine and Marguerite as well.[23]

In recent years, scholars have preferred to see the Breton spinner as a latter day expulsion from Eden, noting that Gauguin returned to the subject of Eve and the loss of Paradise often throughout his career.[24] Robert Welsh, one of the foremost scholars on the art in Henry’s inn at Le Pouldu, sees Gauguin’s spinner fresco as key to determining whether the dining room had a deliberate program. In arguing that the inn’s decorations primarily reflected Gauguin’s preoccupation with the conflicting attractions of heaven and earth, Welsh dismissed the spinner’s identification with the Maid of Orléans as a figure too suggestive of French patriotism. Instead he argues that Gauguin’s Spinner should be regarded as an image of post-Edenic toil:

Apart from Gauguin’s reputation as scarcely a rabid French patriot, the identification [of the spinner as Joan of Arc] seems suspect on other grounds. What would the Maid of Orléans be doing among dunes along the coast, at that moment in her life, and why associate her with spinning yarn and tending cows in the same context? Such symbolic pursuits accord better with the theme of Breton peasant existence as evoked in Gauguin’s letter to Vincent van Gogh, and as a complement to the theme of “labor” in de Haan’s adjacent mural. The angel with the sword, within this context, is most readily explained as representing the biblical theme of human degradation.[25]

Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov similarly posits that there is not enough evidence to prove that Gauguin’s painting “was intended to illustrate a specific sacred or historical legend.” Concurring with Welsh, Welsh-Ovcharov sees the image instead as a general evocation of mankind’s woeful condition after the loss of Paradise:

The theme of spinning not only logically follows upon de Haan’s Scutching Flax, but is a further instance of his general theme of Labour. It is thus more likely that the angel is symbolic here of the expulsion from the Garden of Eden, which ensures a life of toil at spinning and cow-herding, than of a promise of glorious martyrdom.[26]

Henri Dorra is more explicit in identifying the spinner as a fallen woman being pursued by an avenging angel. In The Symbolism of Paul Gauguin, Dorra dismisses the possibility that the spinner is Joan the Maid, noting as evidence to the contrary the angel’s likeness to “latter-day versions of Renaissance altarpieces depicting the vengeful Archangel Gabriel in pursuit of a straying soul,” and the peasant girl’s knowingly suggestive and uncomfortable appearance, which he describes as both “prim” and “smirking.” As Dorra writes:

The girl’s bleary eyes and smirking bow-shaped mouth suggest youthful debauchery, and her awkwardly twisted bare feet, her own discomfiture. The lascivious flowers of the foreground, dark, and irregularly shaped, and dropping, hint at inner sorrow and guilt.[27]

Yet in response to these interpretations of the fresco as a post-Edenic scene of sin and suffering a number of potentially contradictory details might be noted. For example, if one may question the oddity of placing the Maid of Orléans “among dunes along the coast, at that moment in her life,” one might no less inquire about the likelihood of seeing Eve near a Breton beach dressed as a local peasant at any time in her existence.[28] The suggestion that this scene portrays a fallen Eve being expelled also seems curious when one recalls that the Breton girl is in the act of spinning and attending to animal husbandry as the armed angel approaches her. In Genesis (3:17–23), of course, Eve and Adam toil to survive after, not during their expulsion while the angel was driving them from Paradise.[29]

If the spinner’s identification as a latter-day Eve remains speculative, why have some alternatively identified her as an evocation of Joan of Arc? Specifically what support have authors offered in the past for this interpretation of Gauguin’s Breton spinner? And what reasons, if any, still exist for seeing her as the illiterate and charismatic medieval maiden who led the French army in a series of strategic victories against the Anglo-Burgundians, before being apprehended in battle, handed over to her enemies, convicted of heresy in a partisan trial, and burned at the stake as a witch in 1431—all before the age of twenty-one?

The veritable ubiquity of the Joan of Arc’s image in France by the early twentieth century, when the painting was rediscovered, almost certainly contributed to the assumption by some scholars that Gauguin’s humble peasant being approached by an angel was the young heroine who helped to change the course of history. By the time Gauguin’s mural of a spinner visited by an angel came to light in the spring of 1924, Joan the Maid (or Jehanne la Pucelle, as Joan of Arc called herself)[30] was enjoying the historic zenith of her international celebrity.[31] In 1920 (just four years earlier), she was canonized by the Roman Catholic Church, and granted, by the Assemblée Nationale, the honor of a national secular festival to be held annually each May in France.[32] Beginning in the early nineteenth century, the Maid’s life began to inspire hundreds of books, and scores of songs and plays.[33] Her popularity accelerated during the Restoration of the Monarchy (1814–30) and the July Monarchy (1830–48); it became almost unbridled in wake of the Franco-Prussian war (1870–71).[34] During this time, her image was used to sell everything from commercial products ranging from aperitifs, cheese, and dinner bells, to fabrics and perfume. Her life story was highlighted in both secular and Catholic civic and academic manuals,[35] and her name was given to an increasing number of children’s schools, including the Lycée Jeanne d’Arc that Paul Gauguin attended for his final year of formal education in 1864.[36]

Joan of Arc’s life was also the subject of literally hundreds of paintings, prints, and sculptures between 1802 and 1895 in France.[37] In most of these paintings and sculptures, she appeared as a young provincial girl dressed in rustic and humble clothing, usually barefoot in a rural setting being inspired by her voices to take up France’s cause.[38] By the 1890, all the major sites and cities where she lived, fought, and died took pride in possessing one or more public monuments and numerous art works dedicated to her memory, including Orléans, Paris and Rouen—three cities that were all home to Gauguin at significant times in his life.

Orléans was the first city associated with Joan of Arc’s memory that Paul Gauguin lived in. In late 1854, when he was six-years old, he moved there to the home of his grandfather, Guillaume Gauguin, with his widowed mother, Aline Chazal Gauguin, and his older sister Marie.[39] On May 8, 1855, a few months after their arrival, the first statue erected to the Maid of Orléans after the French revolution, Edme-Etienne-François Gois’s Joan of Arc in Battle (Jeanne d’Arc pendant le combat) (1802–4; fig. 2), was moved to the place Dauphine at the head of the Pont Royal in Orléans, a few yards from the Gauguin family residence at rue Tudelle and Quai Neuf.[40] After Gois’s statue was moved to the southern approach to Orléans’s main bridge across the Loire, Gauguin and his family must have passed this monument daily; they may have even enjoyed a direct view of Gois’s Joan of Arc from the windows of their home by the bridgehead. At the same time, a new colossal equestrian bronze of the Maid of Orléans by Jules Foyatier (fig. 3) was inaugurated with great fanfare in the place du Martroi—Orléans’s central square, less than a half-mile north of the Gauguin home on the quai. The inauguration of Gois’s and Foyatier’s sculptures of Joan of Arc came as a part of the special events surrounding the 425th fête de Jeanne d’Arc—the anniversary celebration of the liberation of the city from a 7-month siege by the English during the Hundred Year’s War.

The installation of these Joan of Arc monuments in May 1855 coincided with one of the largest, most expensive and spectacular fêtes de Jeanne d’Arc to date. [41]The festival may have made an enduring impression on the young Gauguin, especially since it was followed during his ensuing nine years in Orléans by annual commemorative celebrations honoring the Maid’s memory; these Joan of Arc festivals were held during the first week of May at sites throughout the city.[42] In 1855, the festival drew over 12,000 out-of-town visitors.[43] It included an elaborate, torch-lit costumed medieval cavalcade; a parade through the city; fireworks; two special exhibitions of paintings and horticulture; bell ringing; cannon-blasts; a grand ball at the Hôtel de Ville attended by a host of dignitaries representing the Emperor; and a High Mass at the Cathédrale de Sainte-Croix presided over by the Bishop of Orléans, Mgr. Félix‑Antoine‑Philibert Dupanloup.[44] In his panégyrique de Jeanne d’Arc (a commemorative sermon on the Maid) on May 8th, this internationally prominent prelate, whose tireless efforts to champion Joan of Arc’s memory earned him the moniker “évêque de Jeanne d’Arc” (Joan of Arc’s bishop) eulogized his city’s historic savior as an industrious, timid, and modest girl from the provinces, who was “solely occupied by working in the fields and at home, spending all of her days spinning . . . and guarding the flocks.”[45] According to Dupanloup, when approached “by angels and saints sent to save France,” Joan responded humbly: “I am nothing but a poor child.”[46] The prelate particularly emphasized her betrayal and above all her immense suffering, which he insisted was the true source of her greatness:

Yes, she is great because she suffered! She is great, because she died for her country, for truth and for justice. She is great, because she met only with abandonment, ingratitude, falsehood, atrocious calumny, bad for good! She is great, not only because she had a bishop for a murderer and judges for executioners, not only because she was sold for the price of a king. . . . She is great because it was a great nation that killed her, a great nation that abandoned her. . . . In my eyes, the flames of her stake are a glorious splendor, and her martyrdom a grandeur above all grandeurs![47]

Dupanloup closed his sermon by calling Joan a “child and martyr.” Likening her to Christ, he stated simply that when she died “as at Calvary, all the executioners wept.”[48]

While Gauguin may not have attended Dupanloup’s sermon during the Joan of Arc festival in 1855, it is difficult to believe that he did not become acquainted with the prelate’s particular admiration for Joan of Arc, or his insistent characterization of the Maid as a humble, suffering child who resembled Christ in her martyrdom (themes Dupanloup sounded again in 1869 in his second panégyrique de Jeanne d’Arc, in which he announced the formal introduction of Joan of Arc’s cause for canonization in a petition to the Pope);[49] for during his boyhood in Orléans, Gauguin studied religion with the charismatic cleric for at least three years when he was a student at the Petit Séminaire de la Chapelle-Saint-Mesmin, the nationally known Jesuit school founded by Dupanloup.[50] Debora Silverman has suggested that Gauguin’s mentality was seminally influenced by Dupanloup’s efforts to cultivate what he called “life, intelligence, and love” in each child through emphasizing self-reflection, idealism, imagination, and empathetic identification with others and with Christ.[51] Gauguin later affirmed the formative significance of his time at Dupanloup’s Petit Séminaire in his journal “Avant et après”:

At eleven I entered the primary school where I made very rapid progress. . . . I think it did me a great deal of good. . . . I believe it was there that I learned, from my earliest youth, to hate hypocrisy, sham virtue, tale-bearing and to distrust everything that was contrary to my instincts, my heart and my reason. There I formed the habit of concentrating on myself, ceaselessly watching what my teachers were up to, making my own playthings, my own griefs as well, with all the responsibilities they bring with them.[52]

After he moved from Orléans, Gauguin had ample opportunity to be exposed to numerous other well-known monuments and art works devoted to Joan of Arc’s memory, especially during the months and years he lived in Paris (1871- 84), and in Rouen (January–November 1884)—the historic site of Joan of Arc’s trial for heresy and where she was burned at the stake in 1431—as well as during his many short visits to Paris between 1884 and 1895.[53] While working as a stockbroker for Paul Bertin, whose offices were on the rue Laffitte in the 9th arrondissement (1872 to the winter of 1876–77), for example, he was a short walk—approximately1 km—from the Louvre, at the foot of which stood Emmanuel Frémiet’s famous gilded equestrian statue of Jeanne d’Arc in the place des Pyramides.[54]

Installed in 1874 on the site of the former porte Sainte‑Honoré, where Joan of Arc fought and was wounded in battle in September 1429, Frémiet’s monument became the center of a politically polarized national debate that lasted for over two years, beginning in 1876 when the aged, ailing, but still indomitable Bishop Dupanloup published a series of letters vehemently opposing plans to commemorate the centenary of Voltaire’s death on May 30th, 1878.[55] Countering efforts to honor the Enlightenment philosopher with a statue in Paris and a national festival, Dupanloup launched his own national campaign to promote Joan of Arc rather than Voltaire as the ideal symbol of France’s true spirit, and he encouraged the women of France to lay wreaths before Frémiet’s sculpture of Joan of Arc on the anniversary of the Maid’s death, which ironically also fell on May 30th.[56] As antagonism grew between pro-Joan Catholic royalists and pro-Voltaire rationalist republicans, the government was forced to step in. Fearing rioting, all demonstrations and commemorations of Voltaire and of Joan of Arc were forbidden in the streets of Paris. While Voltaire’s centennial celebrations went indoors (republicans gathered to celebrate and hear speeches at the Théâtre de la Gaîte and at the Cirque Américain), Catholic partisans passed through the rainy streets of Paris to pay silent homage to the statue of the Maid in the place des Pyramides, and their wreaths were sent together by train, instead, to Domremy.[57] These highly charged and widely-publicized events may have served to keep two figures from Gauguin’s childhood—Joan of Arc, and the “évêque de Jeanne d’Arc”—alive in Gauguin’s imagination when he began his career as an exhibiting artist in Paris.

Gauguin was likely to have seen two or more other very famous images of the Maid in Paris before he returned to Brittany again in the fall of 1889. As Ziva Amishai-Maisels first noted, Gauguin could have seen Jules Bastien-Lepage’s celebrated Joan of Arc (Jeanne d’Arc écountant ses voix) (1879; fig. 4) at the Exposition Centennale de l’Art Français at the Palais des Beaux-Art in Paris (May 6–November 6, 1889), which Gauguin reviewed in Le Moderniste illustré in July 1889.[58] He probably also saw the first of Jules‑Eugène Lenepveu’s murals of Joan of Arc’s life at the Panthéon,[59] which were unveiled shortly before Gauguin left for Pont Aven and Le Pouldu in the fall of 1889.[60] The protagonist in both paintings bears a strong resemblance to the spinner in Gauguin’s fresco in specific ways.

Like Gauguin’s spinner, Lenepveu’s Joan of Arc, Shepherdess in Domremy (Jeanne d’Arc, bergère à Domrémy) (1889; fig. 5) in the Panthéon portrays a young peasant girl outside in a rustic, rural setting, barefoot, guarding livestock with a distaff in her left hand. Eyes fixed open, Lenepveu’s spinner seems almost dumbfounded as a radiant angel descends steeply towards her from behind, preparing to place a sword in her empty right hand as two faint, ghostly specters watch from the high branches of a nearby tree. Widely regarded as anemic in quality, the painting was saved from complete oblivion by its august, historic setting. Bastien‑Lepage’s canvas, which may have lent inspiration to Lenepveu, similarly portrays a humble Maid, interrupted by celestial beings while spinning in her family’s garden. Staring into the distance with an intense but unfocused gaze, she was described aptly by the critic Roger Marx in 1885 as having a “hallucinated face.”[61] The artist’s characteristic attention to naturalistic detail can be seen here in the meticulously described weeds in the overgrown garden that surrounds her, the overturned low stool behind an abandoned spindle in the left mid-ground, the tattered hem of her disheveled dress, and the mud on her awkwardly placed feet, with the middle toes of her left foot curled in.

At the 1889 Exposition Centennale de l’Art Français,Gauguin would likely have encountered not only Bastien-Lepage’s Joan of Arc, but also Léon François Bénouville’s enormous Joan of Arc Listening to her Voices (Jeanne d’Arc écoutant ses voix), which first debuted at the Salon of 1859 (fig. 6).[62] Like Bastien-Lepage’s canvas twenty-years later, Bénouville’s ambitious, larger-than-life-sized painting portrayed Joan of Arc as a wholly astonished barefoot spinner, clutching her distaff in a rustic landscape grazed by livestock, being approached from above and behind by the Archangel Michael. Here, however, Saint Michael bursts from a dramatically stormy sky like a milky ectoplasm upon the beautiful, creamy- skinned maid seated below. The winged saint is accompanied by two other glowing figures whose heads and hands emerge from a steep bank of dark clouds—they are Saint Catherine, who offers the Maid a sword, and Saint Marguerite, who holds a banner. Saint Michael is the most animated figure in the scene; he shouts with open mouth, and plunges in a steep descent towards the Maid with long, rippling wind-tossed hair, broadly outstretched purple wings, and a bright jagged-edged sword. These attributes all make Bénouville’s dramatic archangel a provocative prototype for Gauguin’s own descending angel in his Spinner fresco. As in Gauguin’s fresco, the feet and hands of Bénouville’s Maid also attract attention in a strange, compelling way. In Bénouville’s Joan of Arc Listening to her Voices, her unshorn and lightly soiled feet emerge from beneath her skirts in the painting’s immediate foreground. Because of their prominent placement, the viewer’s eye becomes drawn first to the Maid’s flexed toes, then to the white knuckles of her clenched hands. Together these animated appendages appear to function as a synecdoche for the painting’s implicit claim to the vivid reality of a very surreal situation.[63] While the meaning of the gestural hands and awkward feet of Gauguin’s and Bénouville’s protagonists may not be the same, it is enticing to imagine Gauguin noticing and deliberately reinterpreting in a new synthetic, and perhaps subtly sardonic, manner the reiterated tropes of naturalistic muddy bare feet and theatrically expressive hands that he found in Bénouville, Bastien-Lepage, and Lenepveu.

In each of these paintings, a young peasant is depicted outside spinning and tending animals, facing away from spectral forms that approach from above and behind her. Also in each, one of the Maid’s arms is outstretched as she holds or has just dropped spinning implements. In Lenepveu, it is her right arm; in Bastien‑Lepage and Gauguin, it is her left; and in Bénouville, both arms are extended. With the exception of Bénouville’s canvas, in each of these images the Maid’s hands are open and bent back at the wrist. In Lenepveu’s and Bastien‑Lepage’s portrayals, the Maid’s hand gestures appear to intimate that she is reaching in an overtly theatrical manner for a sword being offered by an unseen spectral visitor. In Gauguin’s fresco, the exaggerated hyperextension of the spinner’s hands evokes a diverse variety of potential sources—ancient Egyptian, Cambodian, Javanese, among others. Gauguin was introduced to imagery from these non-western cultures in the summer of 1889, shortly before he moved to Le Pouldu (as will be discussed further below).[64]

Lenepveu’s Panthéon mural, despite its indifferent quality, was guaranteed importance by its historic placement in the Panthéon’s north transept;[65] and Bastien-Lepage’s painting enjoyed immense popularity when it debuted at the Salon in1880, again in 1885 at the artist’s retrospective at the Hôtel de Chimay following his premature death, and again in 1889 at the Exposition Centennale de l’Art Français.[66] For Gauguin, Bastien-Lepage’s acclaim and the privileged status accorded academic artists such as Lenepveu were enduring sore points. Gauguin disparaged both Bastien-Lepage and the artists of the Panthéon in his final treatise on art critics and art criticism, Racontars de Rapin, penned in 1902. There, among his last words for publication, the gravely-ill Gauguin expressed both scathing incredulity that Bastien-Lepage was embraced as a “very advanced modern artist . . . while he scrupulously digs through all the nooks and crannies of nature,”[67]and outright repugnance for the uninspired and passé academicism of the Panthéon decorations (save Puvis de Chavannes’s portrayals of Sainte Geneviève in the west nave and choir, which Gauguin appears to have genuinely admired):

Where this becomes a page from the history of fin de siècle art, is when one goes to the Panthéon. . . . All that critics could say, all that I could say, becomes useless when one is in the Panthéon. The hordes of Attila vanquished and charmed by little Geneviève are not in these paintings. The barbarians are the painters themselves. Sainte-Geneviève, she is Puvis de Chavannes who drives them from Paris forever. What more beautiful lesson for the painters and critics than that.[68]

Yet if Gauguin scorned the paintings of Bastien-Lepage, Lenepveu, and other artists that enjoyed official success, why might he have chosen to appropriate specific aspects of their work in painting a spinner by the shore in Brittany? Victor Merlhès has suggested that Gauguin may have “exploited the theme of the spinner” in an effort “to make of a young girl from Pouldu a Joan more poetically true than the stereotyped insipidity of Bastien-Lepage and others like Lenepveu.”[69] Given Gauguin’s writings and the competitive personality that emerges from his biography, it seems feasible that derision and the desire to outdo more successful but less innovative artists may have helped to draw Gauguin to a subject that had already suggested itself to his imagination for other reasons.

There are, of course, aspects of Gauguin’s Le Pouldu fresco that defy association with Joan of Arc, Eve, or any prominent Western iconographic precedent, including her distinctive, seemingly exotic hand gestures, which have already been noted above. Henri Dorra, for example, calls the spinner’s gesture “Buddhist,” arguing that Javanese and Khmer art inspired the position of her right hand.[70] Numerous scholars have detailed the diverse influences that affected the artist when he visited the Exposition Universelle on the Champ-de-Mars and the Trocadéro in Paris in the spring and summer of 1889 before he moved back to Brittany. There Gauguin attended at least two performances by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West troupe; he visited the recreation of a Javanese village; acquired photographic reproductions of tomb paintings from ancient Egypt and Buddhist friezes from the Temple of Borobudur in Central Java (both of which the artist kept until his death); and he found a fragment of a reproduction of Cambodian art at the Exposition Coloniale, that he brought to and installed in the dining room at Buvette de la Plage as one of his contributions to the room’s decor.[71] Thus the Breton spinner’s right hand, raised vertically before her chest, hyperflexed at the wrist and bent at the middle of her fingers, and her lowered left hand, also hyperflexed at the wrist with flexed fingers, may have derived from any or all of the following sources—guests at an eternal banquet from ancient Thebian tomb frescos, Angkorian period Khmer guardian angels, the mudras of a Javanese Buddha from the Temple of Borobudur, or the sinuous gestures of Javanese dancers, among other possibilities.

So what does this painting mean? And does it matter whether the spinner is accepted as a latter-day Eve, a Breton-based Joan of Arc, a symbolist combination of the two, or something else altogether? In considering these questions, let us look again at the letter Gauguin wrote to Vincent van Gogh in the early winter (ca. December 13, 1889, which has already been quoted in part above) regarding the decorations at Henry’s inn in Le Pouldu, since it is the artist’s only known contemporary description of the spinner fresco and the circumstances that surrounded its creation. In this correspondence, Gauguin offers a brief reflection on the themes that he was recently pursuing in his work:

In the fever of work, . . . I postponed my letter until later—now let’s chat. Regarding religious paintings, I have done only one this year, and it’s good sometimes to make attempts of every sort, in order to sustain one’s imaginative powers, and one looks at nature afterwards with pleasure. Anyway, all that is a matter of temperament. Myself, what I have done most of all this year are simple peasant children, walking indifferently beside the sea with their cows. . . . I try to put into these desolate figures the savagery that I see in them, and that’s in me too. Here in Brittany the peasants have a medieval air about them and don’t appear to think for a moment that Paris exists and that we’re in the year 1889—quite the opposite of the South.—Here everything is rough like the Breton language, very closed-in (for evermore, it seems). The costumes are also almost symbolic, influenced by the superstitions of Catholicism. Look at the back, bodice a cross, the head wrapped in a black kerchief like nuns—in addition the figures are almost Asiatic, yellow and triangular, severe.[72]

This letter seems revealing in a number of ways. It makes us aware that the artist found Breton peasants evocative of the Middle Ages, Joan of Arc’s own day; that he found their native dress symbolic of their Catholic faith, which he describes further as being superstitious and severe; and that he was thinking of religious painting at the time. Christ in the Garden of Olives (Le Christ dans le jardin des oliviers) (1889; fig. 7) was the one religious painting that Gauguin admits here to having completed recently. In a letter to Vincent van Gogh, sent in early November 1889, Gauguin enclosed a watercolor sketch of this painting, and he described its vibrant palette and use of non-local color:

I have at home a thing I haven’t sent and which would suit you, I think. It’s Christ in the Garden of Olives—sky blue-green, dusk, some trees all bent into a purple mass, ground violet and Christ enveloped in a dark ochre garment with vermilion hair. This canvas isn’t destined to be understood so I’m keeping it for a while.[73]

Gauguin’s conjecture that this painting would please his colleague may reflect his knowledge that Van Gogh had himself recently attempted painting the same subject.[74] Unfortunately, Gauguin’s efforts were not met with the approval he hoped for. Although Van Gogh’s response to Gauguin has been lost, his pique at Gauguin’s treatment of the subject, and his disapproval of a recent rendering of the same scene by their mutual friend Emile Bernard, survive in the form of a scathing letter Vincent sent to his brother Theo in November 1889 from Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, in which he declares his own resolve not to paint any more biblical scenes:

I’ve been working this month in the olive groves, because [Gauguin and Bernard] have angered me with their Christs in the garden, where nothing is observed [from nature]. Of course there’s no question of me doing anything from the Bible—and I’ve written to Bernard and also to Gauguin that I believed that thinking and not dreaming was our duty, that therefore I was astonished by their work, by the fact that they should have stooped to that. [Their paintings] are sorts of dreams and nightmares.[75]

In light of this exchange, it is possible that Gauguin deliberately down-played the symbolic religious content in his Spinner fresco—and in his recent Self-Portrait with a halo, a snake, and tempting ripe fruit (1889; fig. 8)—to avoid inciting more disapproval from his colleague. In a later 1891 interview with the journalist Jules Huret, Gauguin elaborated more freely on his painting of Christ; he also noted that the face of the sorrowing Savior was his own:

There I have painted my own portrait . . . But it also represents the crushing of an ideal, and the pain that is both divine and human. Jesus is totally abandoned; his disciples are leaving him, in a setting as sad as his soul.[76]

From the artist’s words, it is clear that Christ represents for Gauguin an incarnation of suffering and betrayal. It is telling that the artist conspicuously casts himself in the central role, with disciples retreating in the distance in a rolling landscape that (as Debora Silverman has noted) recalls “the dunes and shoreline of Le Pouldu."[77] The artist however gave Christ a hair color that was not his own, and he gave Christ’s skin a dominant yellow tone, and narrowed eyes, which the artist identified as characteristic of native Bretons.[78] (The subtle differences in Gauguin’s skin color and in the shape of the eyes become more clear in comparing Christ’s face with Gauguin’s Self-Portrait, also painted in Le Pouldu.)[79] Thus, as Gauguin shares in Christ’s suffering, Christ shares in the suffering of the Breton people.

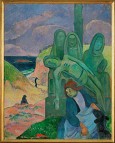

The theme of suffering plays a focal role in a number of Gauguin’s paintings from the fall and winter of 1889, including another important religious painting entitled Green Christ or Breton Calvary (Christ vert or Calvaire Breton) (1889; fig. 9), that shares a number of key formal and thematic elements with both Christ in the Garden of Olives and Breton Girl Spinning. Gauguin endeavored to explain the Breton Calvary in a long and emotionally charged letter to Theo van Gogh, sent around November 20 or 21, 1889. Written in rapid, staccato phrases, the letter was penned with confessed “bitterness” at not being understood by Theo, his art dealer; it includes a self-pitying lament for his straitened circumstances, which have weakened him:

I search at once to express a general state rather than a unique idea, to make felt in the eye of another an indefinite infinite impression. To suggest a suffering not wanting to say what sort of suffering; purity in general and not what kind of purity. . . . Between the possible and the impossible. The same in the painting of 3 women in stone holding Christ. Brittany, simple superstition and desolation.—The hill is guarded by a line of cows disposed as a Calvary. In this tableau, I sought to make everything breathe suffering passive belief, primitive religious style and great nature with its cry. It’s wrong of me not to be strong enough to express this better—but I am not wrong to think it. And about that, we other poor devils without lodgings, without models, we resemble virtuosos who play in a café on a tinny piano.[80]

To the writer Albert Aurier, Gauguin later penned a shorter, less angry, but even more broken and fragmentary description of the Breton Calvary on the front and back of his own calling card:

Calvary, cold stone of the earth—Breton idea of sculpture which explains religion according to the Breton soul, with Breton costumes, local color. A passive lamb. All this in a Breton landscape, which is to say Breton poem. Its point of departure / color animates the entourage, sky, etc. A sad undertaking. In contrast (the human figure) poverty as in life.[81]

The artist’s portrayal of “suffering passive belief,” “simple superstition and desolation,” and the harshness of life circumscribed by “great nature with its cry” can be seen in the towering dunes and pounding white-crested surf in the mid-ground and distance, and in the face and attitude of this melancholy Breton girl seated under the mute stony gaze of a dead Christ and the three mourning Marys on the base of a large Calvary.[82] The Breton girl’s narrow eyes are puffy and red-rimmed, and her face has a yellow cast with green undertones that evokes the startling hue of the chartreuse-green pieta behind her. The young woman’s somber attire—a Breton costume in the “local color”—consists of an aquamarine colored Breton jacket and skirt, dark blue vest, and lighter blue apron, all surmounted by a red scarf or coif.[83] It recalls the even more humble costume worn by the Pouldu spinner.[84] So, too, do her features; both the Maid and the spinner have stubby, thick noses, and—like Christ in the Garden of Olives—sallow skin, slanted “almost Asiatic” eyes, and arched eye-brows. Leaning forward, with her head bowed and right shoulder cast down, her legs inelegantly splayed, and her right forearm hanging before her lap with a rope loose in her limp hand, the girl’s pose also recalls that of the dejected Christ in Gauguin’s Christ in the Garden of Olives.[85] Death, mourning, and the unbroken cycle of suffering (hers, Christ’s, and that of the three women behind her) may be symbolized by the rope she holds, and by the baby lamb (in the right foreground) that thrusts its woolly black head into her lap, as the girl turns away from it absorbed by her own grief.

As in the fresco now known as Breton Girl Spinning and Christ in the Garden of Olives, the girl in Breton Calvary appears before a strong vertical element that bisects the landscape and the composition. Here, the dominant vertical form is the foot of the cross that rises to cleave the sky. In Christ in the Garden of Olives, this vertical element is the trunk of a slender olive tree with narrow, sinuously-bent, leafless branches truncated by the upper edge of the canvas. This tree may foreshadow the cross of Christ’s crucifixion. This leafless slender form appears again, little altered, as the sole tree behind the spinner in Gauguin’s Le Pouldu mural. The background of this barren coastal landscape has no other vegetation save a thin, broken expanse of low grasses on the escarpment rising behind the spinner, and the sinuous tendrils of stylized twisting red flowers in the immediate foreground.[86] In the spinner fresco, the tree is rendered in the same deep aqua-marine blue as the spinner’s dress, making their slender forms meld, rooting her—like the tree beside which she stands—in the sandy soil of Brittany. Vojtěch Jirat-Wasiutyński has suggested that this leafless tree trunk behind the spinner may represent “a reference to the stake at which [Joan of Arc] died.”[87]

In a letter to Vincent van Gogh written in September 1888, Gauguin wrote “the artist’s life is one long Calvary.”[88] In Christ in the Garden of Olives, the artist joins Christ on the road to Cavalry at the start of his passion; in twinning himself with Christ and transportingthe Mount of Olives to the dunes by Henry’s inn, Gauguin and Christ alike now face the suffering of mockery, abandonment, and betrayal. In Breton Calvary, a Breton girl and lamb suffer from poverty, passivity, and primitive superstition. In the spinner fresco at Le Pouldu, a poor thin girl waits by the sea for an angel who brings her destiny—expulsion from Paradise, martyrdom, or both? The question remains.

In Gauguin’s day, Joan of Arc represented more than an unalloyed figure of nationalist patriotism, which was a subject of seeming indifference to the artist. Her pervasive, yet remarkably polyvalent image offered the artist a potentially resonant, richly complex embodiment of rustic visionary faith and suffering in the form of a secular girl who—in Dupanloup’s words—was a child-martyr who like Christ died “at Calvary,” enduring abandonment, betrayal, and condemnation. These forms of bitter rejection were all recurrent themes in Gauguin’s iconography in the fall of 1889. In suggesting that Gauguin may have taken inspiration from Joan of Arc’s image in painting the spinner at Le Pouldu, it is not to say that his fresco paid homage to the French heroine, or indeed to anyone. Too many elements combine to subvert a simple reading of this scene as a single historic—or biblical—narrative. The painting’s Breton location and the spinner’s exotic hand gestures, for example, are alien both to the life of the medieval maiden who saved France and died for that honor, and to the expulsion of Eve from paradise for the sin of disobedience. Numerous ambiguous elements in the composition also have no fixed place in Edenic or Johannique iconography, including sinuous flowers that may represent good or evil, and the small Irish Terrier with a spiked collar by the spinner’s side, that may represent loyalty in suffering or even the artist himself.[89] Instead, the artist seems to have employed deliberately porous and polysemous symbolism.[90] In asking if Gauguin’s fresco of a “Peasant Spinning by the Sea, her Dog and her Cow” at Le Pouldu portrays a spinner or a saint, it seems best to let the artist’s own words have the last say. As Gauguin wrote in November 1889 from the inn at Le Pouldu: “I search at once to express a general state rather than a unique idea, to make felt . . . an indefinite infinite impression. To suggest a suffering not wanting to say what sort of suffering.”[91]

I would like to thank Robert Alvin Adler for his superb editing; my husband, John Emad Arbab, for his invaluable, loving support; my mother, Jeanne M. Heimann, for her enduring, vital inspiration; and my father John J. Heimann, for his emphatic insistence on verbal precision in my childhood, and for his guiding example of boundless intellectual curiosity. I also wish to thank my dear friend Olivier Bouzy, a fellow Joan of Arc scholar, for his invaluable generosity in sharing research over the past two decades; my wise (and remarkably patient) colleagues Petra ten-Doesschate Chu and Gabriel P. Weisberg, for organizing this well-deserved tribute to Patricia Mainardi; and Allison Hope Lipari for her encouragement, which helped to sustain me through the long process of writing this article, and for her generous assistance in checking references, which served in the last moments of revising this text to ensure its accuracy.

[1] Meijer de Haan’s name also appears in the literature as Meyer de Haan (or Jacob Meyer de Haan); in this article, I will be using the Dutch spelling of his name. According to Robert Welsh, Gauguin first registered at Marie Jeanne Henry’s Inn on October 2, 1889 and he departed on November 7, 1890; de Haan registered on October 14, and he departed Le Pouldu for Paris, never to return, in October 1890. Robert Welsh, “Gauguin and the Inn of Marie Henry at Pouldu,” in Gauguin’s Nirvana: Painters at Le Pouldu 1889–90, ed. Eric M. Zafran (New Haven: Wadsworth Athenaeum Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2001), 62–63); originally published as Robert Welsh, “Gauguin et l'auberge de Marie Henry au Pouldu,” Revue de l’art 86, no. 1 (1989), 35–43. Unless otherwise indicated, all citations hereafter are to the English translation.

[2] In this effort, I am particularly inspired by June Hargrove’s insightful approach to Gauguin’s portraits of Meijer de Haan at Le Pouldu. June Hargrove, “Gauguin’s Maverick Sage: Meijer de Haan,” in Visions: Gauguin and his Time, ed. Belinda Thomson, Van Gogh Studies 3 (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum/Waanders Publishers, 2010), 86–111. I am grateful to Patricia Mainardi for first introducing me to Hargrove, when I was a young doctoral candidate.

[3] The earliest published account of Gauguin’s and de Haan’s decorations at Marie Jeanne Henry’s inn, by Charles Chassé, does not include a description of the first frescos painted on the west wall of the dining room, though it offers valuable details regarding the decorations on the room’s other walls and ceiling, as recounted by Henri Mothéré (Henry’s companion in later life), and others. Charles Chassé, Gauguin et le groupe de Pont-Aven: Documents inédits (Paris: H. Fleury, 1921), 25–52, esp. 48). For contemporary images and additional transcribed eyewitness accounts of the Maison Marie Henry in Le Pouldu, see Marie-Amélie Anquetil and others, eds., Le Chemin de Gauguin: Genèse et rayonnement, exh. cat. (Saint-Germain-en-Laye: Musée Départemental du Prieuré, 1985), 110–35. For a historical analysis of the inn’s decorations, see also Welsh, "Gauguin and the Inn "; Victor Merlhès, “LABOR. Painters at Play in Le Pouldu,” in Zafran, Gauguin’s Nirvana, 80–101; and Jean-Marie Cusinberche, ed., Gauguin et ses amis peintres – Collection Marie Henry – "Buvette de la plage", Le Pouldu, en Bretagne, exh. cat. (Yokohama: Le Journal Maiïnichi, 1992), 161–65.

[4] Cusinberche, Gauguin et ses amis peintres, 162–63; Welsh, “Gauguin and the Inn,” 62.

[5] The decorations included a relief fragment that Gauguin found near the Javanese Pavilion in the Exposition Coloniale at the Exposition Universelle in 1889. Chassé, Gauguin et le groupe de Pont-Aven, 40; Hargrove, “Gauguin’s Maverick Sage,” 99, 109n62. Eyewitness accounts and early photographs indicate that one wall was also embellished with a quote from Richard Wagner promising eternal damnation for materialists who “traffic” in art and eternal bliss for the “faithful” who seek artistic purity. For further discussion regarding the possible meaning of this quote in this context, see Welsh, “Gauguin and the Inn,” 62; Hargrove, “Gauguin’s Maverick Sage,” 88; and Debora Silverman, Van Gogh and Gauguin: Search for Sacred Art (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 294–95.

[6] Borrowing factiously from the chivalric motto in Medieval Latin Honi soit qui mal y pense (Shame be to him, who evil thinks) of the British Order of the Garter, Gauguin painted “oni soie ki male y panse” on the ceiling; June Hargrove has translated this risqué phrase as “roughly equivalent to the 'goose who services the male.’” Hargrove, “Gauguin’s Maverick Sage,” 89.

[7] Shortly before de Haan left Le Pouldu in October 1890, Henry conceived a baby girl by him, whom she named Ida Henry after her birth in June 1891. Hargrove, “Gauguin’s Maverick Sage,” 88. According to Henri Dorra, de Haan asked Henry to marry him, but broke the engagement under family pressure before leaving for Paris. Henri Dorra, Symbolism of Paul Gauguin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 102–3. De Haan never acknowledged his daughter. According to June Hargrove, it is not clear if he even knew of her existence before he died of tuberculosis in Holland in 1894. Hargrove, “Gauguin’s Maverick Sage,” 88. Gauguin’s letters from Le Pouldu in the late fall and winter of 1889 to 1890 are particularly marked by strong expressions of concern related to his straitened financial situation; see, for example, Paul Gauguin, Letters to his Wife and Friends, ed. Maurice Malingue, trans. Henry J. Stenning (Boston: artWorks, MFA Publications, 2003), 127–28, 129–31.

[8] Silverman, Van Gogh and Gauguin, 278.

[9] Henry and her daughters Marie-Léa (“Mimi”) and Ida moved first to Moëlan-sur-Mer, where they lived with Mothéré for a year in a rental property, before moving to Kerfany-les-Pins, when the large home Mothéré was having built for them was completed. Anquetiland others, Le Chemin de Gauguin, 127–28.

[10] Ibid., 127; Cusinberche, Gauguin et ses amis peintres, 165.

[11] Anquetiland others, Le Chemin de Gauguin, 123, 125; Cusinberche, Gauguin et ses amis peintres, 165–66.

[12] Anquetiland others, Le Chemin de Gauguin, 127; John Rewald, Post-Impressionism: From Van Gogh to Gauguin, 3rd ed. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1987), 267–72.

[13] According to an early source, the murals were found under “seven layers of wallpaper.” “Peintures de Gauguin,” Le Bulletin de la vie artistique, October 1, 1925, 435–36. See also, Georges Wildenstein, Gauguin (Paris: Les Beaux-Arts, 1964), 1:126, cat. 329; Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, part I. Auction catalogue. Sale number 6415, New York, May 11, 1993 (New York: Sotheby’s, 1993), n.p., no. 39; and Cusinberche, Gauguin et ses amis peintres, 167–8

[14] “Peintures de Gauguin,” 435–36; Wildenstein, Gauguin, 126.

[15] The paintings were sold to two Americans named Abraham Rattner and Isadore Lévy for 20,000 francs. “Peintures de Gauguin,” 436; Rewald, Post-Impressionism, 290n40). According to Welsh-Ovcharov, “Rattner apparently engineered [the frescoes] detachment from the wall” of the inn. Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, Vincent van Gogh and the Birth of Cloisonism, exh. cat. (Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1981), 350n1. According to Life magazine, between 1925 and 1950, when the Spinner fresco was put up for sale again, Gauguin’s mural of a Breton spinner was “hidden away in a storage house with the result that many of the most informed Gauguin scholars do not even know that it exists.” Life 28, no. 18, May 1, 1950, 93.

[16] Wildenstein, Gauguin, 126–27.

[17] Welsh, "Gauguin et l'auberge," 37, fig. 4; Welsh, “Gauguin and the Inn,” 60–61, 79, fig. 88–89, pl. 108.

[18] Among the different titles that have been used for this fresco by prominent scholars, some of whom changed their minds over time regarding the painting’s proper title, are The Spinner or The Spinner (Joan of Arc) (Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, “Paul Gauguin’s Third Visit to Brittany,” in Zafran, Gauguin’s Nirvana, 49, 79, fig. 108); Breton Peasant Girl Spinning (Dorra, Symbolism of Paul Gauguin, 103–4; and Welsh-Ovcharov, Vincent van Gogh and the Birth of Cloisonism, 76, 210–11, fig. 71 and plate 17); and Breton Peasant Girl Spinning by the Sea (“Joan of Arc”) (Silverman, Van Gogh and Gauguin, 287–88, fig. 122).

[19] Contrary to Douglas Cooper, who dates this letter to “environ le 20 octobre 1889” in Paul Gauguin, Paul Gauguin: 45 Lettres à Vincent, Théo et Jo van Gogh, ed. Douglas Cooper (The Hague: Staatsuitgeverij, 1983), 272–79, letter 36, Robert Welsh and Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker assert that Gauguin’s letter to Van Gogh describing the first murals at Le Pouldu was written “on or about Friday December 13, 1889.” Welsh, “Gauguin and the Inn,” 64; and Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent van Gogh - The Letters: The Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition (London: Thames & Hudson, 2009), The Van Gogh Museum, letter 828, accessed March 16, 2012, http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let828/letter.html. This December date is based on correspondence by both de Haan and Gauguin from Henry’s Inn. As Welsh notes, de Haan wrote a lengthy letter to Theo van Gogh on October 22 detailing his work with Gauguin at Le Pouldu that makes no reference to the decoration of their auberge, and Gauguin similarly wrote a letter to Theo on November 8 that discusses in detail the artist’s latest work but that remains silent on the dining room decorations; yet both Gauguin and de Haan wrote letters to the Van Gogh brothers—de Haan to Theo in Paris on December 13, 1889 and Gauguin to Vincent in St. Rémy “just before this date” that report on the completion of decorations on all four walls in their inn’s dining room. Welsh, “Gauguin and the Inn,” 64, 164n22. Based on this epistolary chronology, Welsh and Jansen et al conclude that the murals were begun no sooner than mid-November 1889.

[20] Meijer de Haan, Breton Women Scutching Flax (Labor), 1889, oil on plaster transferred to canvas, private collection.

[21] Gauguin, Paul Gauguin: 45 Lettres, 273, letter 36; Jansen, Luijten, and Bakker, Vincent van Gogh - The Letters, letter 828, http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let828/letter.html. Translation the author’s.

[22] Wildenstein, Gauguin, 126–27; Vojtĕch Jirat-Wasiutyński, Gauguin in the Context of Symbolism (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc, 1978),151–54; Rewald, Post-Impressionism, 272; Ziva Amishai-Maisels, Gauguin’s Religious Themes (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc, 1985), 529, illustration 16; Anquetiland others, Le chemin de Gauguin, 233, cat. 233; Françoise Cachin, Gauguin, trans. Bambi Ballard (Paris: Flammarion, 1988), 116; and Cusinberche, Gauguin et ses amis peintres,162; Merlhès, “LABOR,” 91–93.

[23] According to Joan of Arc’s own testimony, given during her trial for heresy on February 27, 1431, Saint Michael first spoke to her, bringing revelation from God, when she was about 13 years old (that is ca. 1425); in her testimony in early March 1431, she gave the names of the other saints who later spoke to her as well—Saint Catherine and Saint Margaret. Pierre Tisset and Yvonne Lanhers, eds., Procès de condamnation de Jeanne d’Arc, édité par la Société de l'histoire de France, Fondation du Département des Vosges (Paris: Librairie C. Klincksieck, 1970), 2:72–73, 136–37.

[24] Many articles have been published on Gauguin’s interest in the image of Eve and the Fall, including Ziva Amishai-Maisels, “ Gauguin’s 'Philosophical Eve,’” Burlington Magazine 115, no. 843 (June 1973): 373–79, 381–82; Thomas Buser, “Gauguin’s Religion,” Art Journal 27, no. 4 (Summer 1968): 375–80; Henri Dorra, “The First Eves in Gauguin’s Eden,” Gazette des beaux-arts 6, no. 41 (March 1953): 189–202; and Vojtěch Jirat-Wasiutyński, “Self-Portrait with Halo and Snake: The Artist as Initiate and Magus,” Art Journal 46, no. 1 (Spring 1987), 22–28. Among the books that deal in a sustained manner with these related themes in Gauguin’s oeuvre may be included as well Amishai-Maisels’s Gauguin’s Religious Themes; Dorra’s Symbolism of Paul Gauguin, and Jirat-Wasiutyński's, Paul Gauguin in the Context of Symbolism.

[25] Welsh, “Gauguin and the Inn,” 65.

[26] Welsh-Ovcharov, Vincent van Gogh and the Birth of Cloisonism, 210.

[27] Dorra, Symbolism of Paul Gauguin, 103.

[28] The possibility that Gauguin might have represented Joan of Arc—or Eve—in a Breton costume along the Atlantic shore in this fresco, however, may seem arguably more plausible when one recalls that little more than a year after leaving Le Pouldu, Gauguin cast the Virgin Mary in Ia Orana Maria (1891) as a Tahitian in a traditional flowered pareu in a Polynesian landscape.

[29] It might also be noted that Gauguin appears to have systematically avoided including the “cherubim” wielding a “fiery revolving sword” (as described in Genesis 3:24) in all of his other images of Eve during or after her fall, including Martinique Eve (1887, carved oak relief), Breton Eve (1889, pastel and watercolor on paper), Exotic Eve (1890, oil on cardboard), Eve and the Serpent (1896, carved wood relief), Eve (1898–99, woodcut print), and even his late Adam and Eve (1900, monotype).

[30] Joan of Arc's given and surnames were recorded in a variety of ways in her own day and afterward. In signing official documents, Joan used neither of her parent's surnames, preferring Jehanne (Joan) or Jehanne la Pucelle (Joan the Maid). French contemporaries of hers often called Joan “la Pucelle d’Orléans” (the Maid of Orléans) in honor of her leading role in lifting the year-long siege of Orléans by the English in 1429, a decisive victory that helped to turn the Hundred Year’s war in France’s favor. Marina Warner, Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981), 22; and Nora M. Heimann, Joan of Arc in French Art and Culture (1700–1855): From Satire to Sanctity (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2005), 1, 2n3.

[31] In 1920, she was hailed on both sides of the Atlantic as “the heroine of patriots everywhere.” New York Tribune, quoted in Literary Digest 65, June 5, 1920, 47. For more on Joan of Arc’s cult in America, see Laura Coyle, “A Universal Patriot: Joan of Arc in America during the Gilded Age and the Great War,” in Joan of Arc: Her Image in France and America, ed. Nora M. Heimann and Laura Coyle (London: D Giles Ltd, 2006), 52–73; and Robin Blaetz, Visions of the Maid: Joan of Arc in American Film and Culture (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001).

[32] Quoted in Michel Winock, “Joan of Arc,” in Realms of Memory: The Construction of the French Past, vol. 3, Symbols, ed. Pierre Nora, trans. Arthur Goldhammer, English edition ed. Lawrence D. Kritzman (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), 467–68; and Gerd Krumeich, Jeanne d’Arc à travers l'histoire, trans. Josie Mély, Marie‑Hélène Pateau, and Lisette Rosenfeld (Paris: Editions Albin Michel S.A., 1993), 251.

[33] Heimann, Joan of Arc in French Art and Culture, xii, 45–98. For lists of the many works portraying the Maid produced in the 19th century, see also Pierre Lanéry d’Arc, Le Livre de Or de Jeanne d’Arc: Bibliographie raisonnée (Paris: Techner, 1894); Emile Huet, Jeanne d’Arc et la musique: Bibliographie musicale (Orléans: Librairie Jeanne d’Arc, 1909); Altha Elizabeth Terry, Jeanne d’Arc in Periodical Literature (New York: Institute of French Studies, 1930); and Nadia Margolis, Joan of Arc in History, Literature and Film: A Select, Annotated Bibliography (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1990).

[34] For more information on the rapid rise of Joan of Arc’s image between the Restoration of the Bourbon monarchy and the Second Republic, see Heimann, Joan of Arc in French Art and Culture, 99–176; for more on the almost explosive expansion of the Maid of Orléans image after the Franco-Prussian war, see Albert Boime, “The Third Republic,” in Hollow Icons: The Politics of Sculpture in 19th-Century France (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1987), 88–92; and Krumeich, Jeanne d’Arc à travers l'histoire, 177–244.

[35] During the Third Republic, illustrations of Joan of Arc’s life appeared more often in French children’s history textbooks than that of any other historic figure except Napoléon. Marc Tourret, "L’historien, vecteur de l’héroïsation," in Odile Faliu and Marc Tourret, Héros, d'Achille à Zidane, exh. cat. (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 2007), 103–4; Christian Amalvi, Les Héros de l’histoire de France (Paris: Phot’Oeil, 1979), 141n78; and Margaret H. Darrow, “In the Land of Joan of Arc: The Civic Education of Girls and the Prospect of War in France, 1871–1914,” French Historical Studies 31, no. 2 (Spring 2008): 280.

[36] Nancy Mowll Mathews, Paul Gauguin: An Erotic Life (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 14.

[37] Emile Arthes, Liste chronologique des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, architecture, gravure & lithographie concernant Jeanne d’Arc, qui ont été admis aux expositions annuelles de Paris, de l'origine à nos jours (Orléans: H. Herluison, 1895). For more information on the proliferation of Joan of Arc imagery, see Images de Jeanne d’Arc Hommage pour le 550e anniversaire de la libération d'Orléans et du sacre, exh. cat. (Paris: Hôtel de la Monnaie, 1979); Joan of Arc: Loan Exhibition Catalogue. Paintings, Pictures, Medals, Coins, Statuary, Books, Porcelains, Manuscripts, Curios, Etc. Under the Auspices of the Joan of Arc Statue Committee, exh. cat. (New York: The Museum of French Art, French Institute in the United States, and the American Numismatic Society, 1913); Philippe Martin, ed. Jeanne d’Arc: Les Métamorphoses d’une héroïne (Nancy: Editions Place Stanislas, 2009); and H[enri] Wallon, Jeanne d’Arc: Edition illustrée d'après les monuments de l'art depuis le quinzième siècle jusqu'à nos jours (Paris: Librairie de Firmin‑Didot, 1876); and Winock, "Joan of Arc." For more on the Maid’s image in the nineteenth century, see Heimann, Joan of Arc in French Art and Culture; and Laurent Salomé and others, Jeanne d’Arc: Les tableaux de l'histoire, 1820‑1920, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musée Nationaux, 2003); and Krumeich, Jeanne d’Arc à travers l'histoire.

[38] The next most common settings for Joan’s image were (in the following order): her portrayal in battle wearing a suit of armor—usually carrying a banner; her captivity in prison—often praying for inspiration; and her last moments at the stake surrounded by her enemies as her pyre is lit. In the many monumental statues of her, by contrast, Joan was usually depicted in armor, often on horseback, and most commonly with her eyes lowered or elevated in prayer.

[39] Isabell Cahn, “Chronology: June 1848-June 1886,” in Richard Brettell and others, Art of Paul Gauguin, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1988), 2; and Mathews, Paul Gauguin: An Erotic Life, 12.

[40] Edme-Etienne-François Gois fils’s Jeanne d’Arc was first inaugurated in 1804 in the place de la République (as Orléans main square, the place du Martroi, was renamed after the Revolution). In 1855, Gois’s statue was removed from the place du Martroi (as the place de la République was now known again) to make room for Foyatier’s statue, and it was given a new home in the place Dauphine at the head of the Pont Royal (renamed the Pont George V after World War II). For more information on Gois’s statue, which was moved one block to the east—to its current location in the rue des Tournelles—after the Second World War, see Heimann, Joan of Arc in French Art and Culture, chap. 3.

[41] Antoine Prost, “Jeanne à la fête identité collective et mémoire à Orléans depuis la Révolution française,” in Christophe Charle and others, eds., La France démocratique: Combats, mentalités, symboles; Mélanges offerts à Maurice Agulhon (Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 1998), 384; Th[éophile] Cochard, Les Fêtes de Jeanne d’Arc à Orléans (Orléans: Marcel Marron, 1907), 48, 50–60; and Léonce Dupont, Les trois statues de Jeanne d’Arc, ou Notices sur les monuments élevés à Orléans en l'honneur de Jeanne d’Arc (Orléans: H. Herluison, Libraire, 1861), 102.

[42] Jacques-Henri Bauchy, Une Fête pas comme les autres: 550 ans de fêtes de Jeanne d’Arc (Orléans: Imprimerie Nouvelle, 1978), 66–71.

[43] Ibid., 64.

[44] Ibid., 64–65; Ville d’Orléans, 426e Anniversaire de la délivrance de la Ville, Inauguration de la Statue Equestre de Jeanne d’Arc et de la Hotel-de-Ville d’Orléans, Fêtes de 6, 7, 8 et 9 Mai, Programme (Orléans: Imp. De Paguerre, 1855), n.p.; and Cochard, Les Fêtes de Jeanne d’Arc à Orléans, 50–60.

[45] Félix-Antoine-Philibert Dupanloup, Panégyrique de Jeanne d’Arc, prononcé dans la Cathédrale de Sainte‑Croix, le 8 Mai 1855 (Orléans: Gatineau, Libraire, 1855), 8. Dupanloup galvanized the drive toward Joan of Arc’s beatification and canonization in the nineteenth century; he was also an influential educational reformer, a powerful conservative Catholic activist, and a prolific, widely-published theologian. Heimann, Joan of Arc in French Art and Culture, 140n19; Adrien Dansette, Religious History of Modern France (NY: Herder and Herder, 1961), 1:237–38; and Silverman, Van Gogh and Gauguin, 122.

[46] Dupanloup, Panégyrique de Jeanne d’Arc, 8.

[47] Ibid., 33–34.

[48] Ibid., 40. Despite being a liberal republican with well-known anti-clerical sentiments, the prominent nineteenth-century historian Jules Michelet also characterized the Maid as a pious, Christ-like martyr whose self-sacrifice delivered the French people. In his Jeanne d’Arc (a revised study of the Maid’s life extracted from his famous multivolume Histoire de France, that was republished in a separate volume in 1853), Michelet further likened Joan to the Virgin Mary and to Christ in her humility, purity, and suffering. Heimann, Joan of Arc in French Art and Culture (1700–1855), 138. We know that Vincent van Gogh, who was particularly fond of Michelet, read his Jeanne d’Arc, for he wrote to Theo in March 1875 notifying his brother that he had just sent to him copies of Ernest Renan’s Vie de Jésus and Jules Michelet’s Jeanne d’Arc. Jansen, Luijten, and Bakker, Vincent van Gogh - The Letters, March 6, 1875, letter 30, http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let030/letter.html. It is not known, however, if Vincent van Gogh ever discussed Michelet’s popular biography with Paul Gauguin, or if Gauguin ever read the account on his own.

[49] Félix‑Antoine‑Philibert Dupanloup, Second panégyrique de Jeanne d’Arc, prononcé dans la Cathédrale de Sainte‑Croix le 8 mai 1869, par Mgr. L'Evêque d'Orléans (Orléans: Imprimerie de G. Jacob, 1869).

[50] Michel Gand, Monseigneur Dupanloup, Evêque d’Orléans (1849–1878) (Orléans: Societe archeologique et historique de l’Orléanais, 1978), 12–13; and Silverman, Van Gogh and Gauguin, 122.

[51] Silverman, Van Gogh and Gauguin, 122–23, 131.

[52] Paul Gauguin, Paul Gauguin’s Intimate Journals, trans. Van Wyck Brooks (New York: Liveright, 1949), 249.

[53] Ibid., 226–28; Cahn, “Chronology: June 1848-June 1886,” 4–5.

[54] Cahn, “Chronology,” 4–5. Walking this route in modern Paris takes about15 to 20 minutes. Historic maps indicate the distance is approximately 17-blocks; the Paris stock exchange was an even shorter distance (approximately 1/2 km) from Frémiet’s famous Joan of Arc in the place des Pyramides. See, for example Plan géométral de Paris et de ses agrandissements à l'échelle d'un millimètre pour 10 m. (1/10,000) (Paris: E. Andriveau-Goujon, 1869), University of Chicago Digital Preservation Collection, Paris in the 19th century, accessed March 15, 2012, http://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/su/maps/paris/G5834-P3–1869-P5.html.

[55] Dupanloup’s 1876 letters to the Municipal Council of Paris were subsequently distributed to all of the parishes in France. In these missives, the bishop charged that any official recognition of Voltaire would cause the destruction of religion in France, and, in a letter to the Senate, he asked that the government intervene to prevent the progress of events that he argued would incite such impassioned religious conflict in France that a true civil war could follow. In response to Dupanloup’s efforts, the minister of the interior forbade all official participation in the preparations for a Voltaire commemoration. Krumeich, Jeanne d’Arc à travers l'histoire, 199. To Dupanloup, the proposal that France commemorate Voltaire’s death in 1878 was an abomination both because the philosophe wrote an infamous pornographic satire on Joan of Arc’s life, and because Voltaire had the coincidental ill-fortune to die on the same day—May 30th (albeit 347 years later)—as Joan of Arc. In one of his many letters to the Paris Council opposing Voltaire’s Centenary, Dupanloup expressed outrage that the man who “insults the people, insults France, . . . [and] Joan of Arc” might be honored on the very day that the Maid died. Félix-Antoine-Philibert Dupanloup, “Septième letter: Voltaire et Jeanne Arc, profounde immoralité de Voltaire,” in Nouvelles Lettres a MM. le Membres du Conseil Municipal de Paris sur la Centenaire de Voltaire par M. L’Evêque d’Orléans (Paris: Librairie de la Société Bibliographique, 1878), 44. For more on the impact of Voltaire’s epic parody La Pucelle d’Orléans, which was penned in the 1730s and circulated in pirated manuscript and later numerous clandestine print editions before Voltaire released his first authorized edition in 1762, see Heimann, Joan of Arc in French Art and Culture (1700–1855), 13–43.

[56] As a sign of popular support for Joan of Arc, Dupanloup also called upon the faithful of France to give money for a set of new stained glass windows celebrating the Maid’s life in Orléans’s Cathedral (replacing windows destroyed in the Franco-Prussian war); and he asked the women of France to prove that “traditional faith” was not dead in their nation by initiating the “solemn veneration” of Joan of Arc. Dupanloup died of cancer in October 1878, before the project could be realized (the new windows were not installed until1897), but his efforts to mobilize Catholics by enlisting their support for Joan of Arc endured through the nineteenth century. Chantal Bouchon, "Les verrières de Jeanne d’Arc: Exaltation d'un culte a la fin du XIXe siècle,” Le Vitrail au XIXe siècle in Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l'ouest 93, no. 4 (1986): 420–25; see also Chantal Bouchon, “Verrières de Jeanne d’Arc: Participation des artistes manceaux aux concours d’Orléans à la fin du XIXe siècle, Eugène Hucher, Albert Maignan, Lionel Royer,” Revue historique et archéologique du Maine 149, no. 18 (1998): 245–47. Led by the duchesse de Chevreuse, president of the “Femmes de France” (a committee of conservative Catholic women devoted to Joan of Arc), Dupanloup’s movement resulted in the creation of a new monument to the Maid at her family home in Domremy, followed by the creation of a basilica to her honor in nearby Bois Chenu that was completed in the early 20th century. Krumeich, Jeanne d’Arc à travers l'histoire, 204–8.

[57] Robert Gildea, The Past in French History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), 157.

[58] Dickson, “Chronology,” 227.

[59] Lenepveu’s five-part Vie de Jeanne d’Arc cycle on the Eastern wall of the north transept at the Panthéon was completed between 1886 and January 1890; it consisted of four large panels portraying the Maid’s inspiration at Domremy, her victory at Orléans, the triumph of the King’s coronation at Reims, and her death at the stake in Rouen, surmounted by a frieze depicting her departure from Vaucoleurs and her capture at Compiègne.

[60] Amishai-Maisels, Gauguin’s Religious Themes, 54–55. Most scholars who concur with Amishai-Maisels's identification of the Breton spinner as Joan of Arc, similarly assert that Gauguin’s fresco may have been influenced by Bastien-Lepage’s and Lenepveu’s images of the Maid; see, for example, Merlhès, “LABOR,” 91–93, and Silverman, Van Gogh and Gauguin, 289–90.

[61] Roger Marx, “J. Bastien-Lepage,” La Nouvelle Revue 34 (May-June 1885), 198, quoted in Richard Thomson, “Seeing Visions, Painting Visions: On Psychology and Representation under the Early Third Republic,” in Thomson, Visions: Gauguin and his Time, 142, 160n17.

[62] Salomé and others, Jeanne d’Arc: Les tableaux de l'histoire, 163, cat. 19.

[63] It might be noted that Bénouville’s painting was almost certainly an important source for a later Joan of Arc history painting: Eugène Romain Thirion’s Jeanne d’Arc, which was shown at the Salon des Beaux-Arts in 1876—the same year that Gauguin’s first painting was exhibited at the Salon. Salomé and others, Jeanne d’Arc: Les tableaux de l'histoire, 60–62, 173, cat. 27; and Brettell and others, Art of Paul Gauguin, 5. In Thirion’s dramatic setting, Joan of Arc is again depicted as a humble, barefoot, and wholly astonished spinner, frozen and staring blankly as she clutches a distaff and spindle in a remote, rock-strewn landscape. As in Bénouville’s earlier painting, the Archangel Michael here emerges from swirling clouds against a dark, stormy sky, and he similarly hurtles toward the Maid from above and behind with spread wings and an outstretched sword.

[64] Amishai-Maisels likens the spinner’s “hieratic” pose simply to that of “the left hand worshiper in Ia Orana Maria” from 1891. Amishai-Maisels, Gauguin’s Religious Themes, 56. The research of Bernard Dorival, Douglas Druick, and Peter Zegers, and others, allow us to identify some of the vast scope of diverse Asian and North African sources that influenced Gauguin in crafting many of his paintings and sculptures at Le Pouldu, including his self-portrait canvas and spinner fresco.

[65] The Vie de Jeanne d’Arc commission was initially granted to Paul Baudry, a prominent academician famed for his celebrated murals in the foyer of the Opéra (inaugurated 1875), by Philippe de Chennevières, the directeur des Beaux-Arts. Upon Baudry’s premature death in 1886, Chennevières reassigned the mural commission to Lenepveu, another leading academician, who also contributed to the ceiling decorations at Garnier’s new Opéra. Pierre Vaisse, “La Peinture monumentale au Panthéon sous la IIIe République,” in Le Panthéon: Symbole des révolutions, de l'église de la nation au Temple des grandes hommes, exh. cat. (Quebec: Centre Canadien d'Architecture, Picard Editeur, 1989), 254–55, 258; and François Macé de Lépinay, Peintures et sculptures du Panthéon (Paris: Editions du Patrimoine, 1997), 34–35.

[66] Marie-Madeleine Aubrun, Jules Bastien-Lepage, 1848–1885: Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre (Paris: Imprimerie Chiffoleau, 1985), 172, no. 249; and Arthes, Liste chronologique des ouvrages de peinture, 20, no. 177).

[67] Paul Gauguin, Racontars de rapin (Paris: Editions Falaize, 1951), 29–30.

[68] Ibid., 71–72.

[69] Merlhès, “LABOR,” 93.

[70] Dorra, Symbolism of Paul Gauguin, 103.

[71] Merlhès, “LABOR,” 81–89, 93; Welsh,“Gauguin and the Inn,” 66; Welsh-Ovcharov, “Paul Gauguin’s Third Visit to Brittany,” 30; Belinda Thomson, ed., Gauguin: Maker of Myth (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010), 135; Bernard Dorival, “Sources of the Art of Gauguin from Java, Egypt and Ancient Greece,” Burlington Magazine 93, no. 577 (April 1951): 118–23; Chassé, Gauguin et le groupe de Pont-Aven, 40; and Hargrove, “Gauguin’s Maverick Sage,” 109n62.

[72] Gauguin, Paul Gauguin: 45 Lettres, 275, letter 36; Jansen, Luijten, and Bakker, Vincent van Gogh - The Letters, letter 828, http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let828/letter.html

[73] Gauguin, Paul Gauguin: 45 Lettres, 283, letter 37. (Translation the author’s.) Cooper dates this letter to “environ 8 November 1889.” In Jansen, Luijten, and Bakker, Vincent van Gogh - The Letters, letter 817, http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let817/letter.html, this same letter is dated “between about Sunday, 10 and Wednesday 13 November 1889.” About three days later, Gauguin also wrote to Emile Bernard, who had recently sent to him and to Van Gogh photographic reproductions of his own recently completed painting of Christ in Gesthemane (1889, now lost). Mary Anne Stevens and others, eds., Emile Bernard 1868–1941: A Pioneer of Modern Art, exh. cat. (Mannheim: Städtische Kunsthalle, 1990), 54–55, fig. 18. In his letter to Bernard, Gauguin expressed surprise that his younger colleague had chosen the same subject, and his reluctance to share his painting of Christ with his painting dealer Theo van Gogh: “A strange coincidence: I have done the same subject, but in another way. I am keeping this painting; it’s no use my showing it to [Theo] van Gogh; it would be understood even less than the rest.” Gauguin, Letters to his Wife and Friends, 132, letter 95; also quoted in Brettell and others, Art of Paul Gauguin, 162.