The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

|

Crisis and Resolution in Vuillard's Search for Art Nouveau Unity in Modern Decoration: Sources for 'The Public Gardens' |

|||||

| Though the impact of Japanese art is more readily discerned in the work of Bonnard, the Nabi "très japonard," it is arguably no less consequential for the art of his intimate friend and fellow Nabi, Edouard Vuillard. Vuillard's first exposure to the art of Japan was probably through S. Bing's review Le Japon artistique (published between 1888 and 1891), a number of issues of which are still in the hands of Vuillard's descendants. Bing's superbly illustrated publication introduced an entire generation of artists to an "art nouveau" that was, as Bing anticipated, to have a profound effect on contemporary artistic creativity and innovation.1 While some of Vuillard's slightly older, avant-garde contemporaries were taken personally by Van Gogh to Bing's gallery and storeroom to leaf through huge piles of Japanese woodblock prints,2 Vuillard himself probably did not have the opportunity to examine a comprehensive group of original ukiyo-e prints until Bing's legendary exhibition opened at the École des Beaux-Arts in April 1890.3 This unprecedented exhibition, which included some 725 Japanese woodblock prints and 421 illustrated books, most likely inspired Vuillard to begin his own ukiyo-e collection—a collection which eventually grew to include some three hundred numbers.4 It is in large part through the study of Japanese prints that Vuillard evolved the astonishing formal innovations arrived at in his watercolor series of the celebrated French actor Coquelin cadet (Private collection). Vuillard's Coquelin watercolors, depicting the comedian in a number of his dramatic roles from the 1890-91 season at the Comédie Française, are exceptional in the artist's oeuvre for their great verve and freedom of execution. Vuillard's bold simplification of form, his use of silhouette, unmodeled color and linear arabesque, indicate the force exerted by Japanese prints on much of Vuillard's art in 1890. John Russell was the first to remark on the japonizing, caricatural quality of the Coquelin cadet watercolors, comparing them to actors prints by Sharaku.5 Although the recent recovery of Vuillard's unpublished collection of Japanese prints has revealed that Vuillard owned no prints by this great eighteenth century master, it is now known that he did own a large number of nineteenth century actors prints by Kuniyasu, Kunimasu, Kunisada, and Kuniyoshi.6 | ||||||

| Vuillard's conception of pictorial space as well as the use of shifting viewpoints in many of his paintings executed between 1890 and 1891 owes much to the art of the ukiyo-e print. In a number of paintings that Vuillard exhibited at Le Barc de Boutteville in November of 1892, Vuillard experiments with varieties of station points, and in particular the vue plongeante or high viewpoint. Vuillard had previously used a high station point in certain of his 1890 landscapes and at least once in an important figural composition, the cloisonné Dressmakers (Private collection).7 Now elaborate interiors, mainly scenes of women seated around tables, are depicted from this point of view, permitting Vuillard to imply a considerable degree of spatial recession without compromising the supremacy of the picture's surface. Floors and table tops are tipped up so that they appear to flow uninterrupted into rear planes which are in turn drawn forward by virtue of their participation in the picture's two-dimensional ornamental continuum. | ||||||

| One of the most forward-looking paintings that Vuillard chose to show at the 1892 Le Barc de Boutteville exhibition is his well-known composition Under the Lamp (Musée de l'Annonciade, St. Tropez).8 In Under the Lamp, Vuillard again employs the high viewpoint which characterizes a number of his contemporary scenes, but now without the same consistency: while the floor and the upholstered armchair in the foreground are tilted up, as if seen from higher up, the two figures are seen at eye level, "in elevation." Perucchi-Petri has observed that this use of different station points within the same picture is commonly found in 19th-century Japanese prints portraying courtesans in interiors.9 In Under the Lamp, however, Vuillard deviates from these models in at least one important respect; here, it is not only the two figures that are seen at eye level, but also the table at which the women are seated, as well as the walls behind them and indeed the entire upper half of the picture. In other words, the two viewpoints employed by Vuillard in Under the Lamp do not overlap one another, but each is assigned and confined to a single part of the horizontally divided picture. Crossing from one zone into the other, the viewer can have the strange impression of having suddenly either stood up or sat down. | ||||||

| The rather covert strangeness of Under the Lamp is further enhanced by the idiosyncratic handling of pictorial space. Complementing the two different station points are two contrasting, co-existent spatial conceptions. In the bottom half of the picture, the viewer reads Vuillard's inclined perspective from the lower right-hand corner along a diagonal path established by the spaced arms of the upholstered chair and legs of the wooden chair at the left. This diagonal recession is reinforced by the background wall with double black panels (the second quarter from the left in the back), the actual disposition of which can be made out with the help of a jutting corner visible behind and underneath the table. In the upper portion of the picture, however, indicators of spatial recession are absent, and here the picture reads naturally from left to right, and the various planes of the walls flatten into a single continuous plane which is drawn forward into the picture's surface largely through Vuillard's projection of dark silhouettes on light ground and light silhouettes on dark ground—effects of clair-obscur which combine with these spatial ambiguities, and with the tantalizing glimpses of the two faces turned away from us, to permeate an ordinary bourgeois interior with a haunting aura of symbolist mystery. | ||||||

| The principal source of inspiration for Vuillard's adaptation of shifting viewpoint and alternating spatial conceptions in Under the Lamp is once more to be found in Japanese woodblock prints. Vuillard's most significant debt is not to Japanese interior views, but, surprisingly, more to landscapes, and in particular those by Hiroshige, whose prints make up the bulk of Vuillard's ukiyo-e collection. Hiroshige's New Shrine at Kanda, from the Famous Views in Edo series, may have even served as a model for Under the Lamp, with its space-flattening device of the tree silhouettes suggesting the dispositions of Vuillard's shadow play. As striking as Hiroshige's juxtaposition of contradictory spatial systems and station points may seem in his landscape views, they seem even more radical when adapted for the impagination of Vuillard's small intimate interiors. Vuillard's exploratory mutations of traditional spatial representation become a preoccupying concern of his future easel painting and will undergo many surprising developments and transformations. | ||||||

| During November 1892, in addition to exhibiting at the Barc de Boutteville, Vuillard also designed a five-panel folding screen for M. and Mme Desmarais to complement over-door panels he had painted for their Paris salon earlier that year.10 A noteworthy new feature of the Desmarais Screen is its unconventional format: five panels of uneven height grouped asymmetrically. From the beginning of the screen's conception, Vuillard seems to have had in mind a variant of standard Japanese folding screens. More surprisingly, there is convincing visual evidence suggesting that a number of Vuillard's later large-scale, multi-panel decorations also owe an important debt to Japanese sources. Ursula Perucchi-Petri, in her important study Die Nabis und Japan11 even speculated that Vuillard's most celebrated Nabi decoration, The Public Gardens (1894)12, might have had a Japanese model as its point of departure. Struck by the absence of any hierarchy among the nine panels of The Public Gardens (figs. 1-9), as well as by the idiosyncratic rhythms Vuillard developed to unify his decorative cycle, Perucchi-Petri hypothesized that Vuillard might have found the dominant pictorial idea for his decoration in either a Japanese folding screen or a ukiyo-e woodblock triptych.13 The confirmation and substantiation of Ursula Perucchi-Petri's intriguing, but hitherto unexplored proposition is the final goal of the present paper. First, however, we must consider at some length the difficulties Vuillard experienced conceiving The Public Gardens and the trying, frustrating circumstances that ultimately led him to adopt a Japanese folding screen as the prototype for his nine-panel decoration. | ||||||

|

The Public Gardens was commissioned by Alexandre Natanson, co-founder of the Revue blanche and eldest of the Natanson brothers, to decorate the salon of his sumptuous Parisian townhouse, located at 60 avenue du Bois de Boulogne, now 74 avenue Foch.14 Though Vuillard's autobiographic summaries record the Alexandre Natanson panels as painted during August and September of 1894,15 the first mention of a new decorative commission occurs in a journal entry Vuillard made as early as January of that year.16 After this entry, Vuillard writes nothing in his journal until July 1894, when a visit to the Cluny Museum has the effect of considerably advancing what still seem to be rather tentative ideas concerning the art of decoration:

The successful example of the Desmarais Screen is behind Vuillard's first ideas for the subject of his new decoration. On a sheet now in the Musée d'Orsay, Vuillard had drawn rough sketches for nine panels with proportions closely approximating those ultimately painted for the cycle.18 At this initial stage, however, the panels clearly propose women in interiors, rather than public gardens, as subjects. The ensemble would have been something like an expanded version of the Desmarais Screen. No other record of this project survives, but by 23 July the subject had been changed to include at least one public garden,19 and a second sheet, one covered almost entirely with vignettes of Parisian omnibuses and pedestrians, is the first visual document to inform us of Vuillard's change of mind.20 In the upper left-hand corner of this page we make out seven of the Natanson panels, six of which are seen as if installed in the salon. All represent garden subjects, but only the seventh panel (just to their right) remotely anticipates the last panels of the future ensemble, with tree trunks and a figure below, and the top full of foliage. |

||||||

|

What Vuillard writes in his journal during the remaining weeks of July and the first half of August constitutes a remarkable record of the extreme difficulties he encountered while painting the picture now known as the Square de la Trinité (fig. 10).21 These entries demonstrate not only that the Square was painted just before the definitive series of The Public Gardens, but more importantly, that Vuillard originally undertook the picture as the first executed part of the Natanson decoration. On 23 July, he notes: "Tranquillity of summer days. No nervousness. In passing by the square complete feeling of summer not only by the sight. Trees from below."22 Just below this entry are three profile drawings of a seated woman.23 In one the figure is shown holding a child. The following day Vuillard writes: "I go down to the square. The same woman as yesterday comes to sit on my bench." A description follows: "dress with little checks, creases without suppleness, like paper, black blouse, and old creases without fullness. white apron. quality of creases small and dry, hair like wet seaweed, hard, mat complexion, purplish lips today. The pallid child sad from weather. silky hair, stiff white linen. lead red ribbon. Gray weather. corner more heavily planted than I thought. Purplish-blue flowers. Impression."24 Vuillard has found both the subject and the setting for his first panel; and the motifs that he will invent and arrange as he works to compose the Square will be but formal equivalents or "signs" of the sensations Vuillard felt while seated on a Paris park bench beside a nursemaid and her charge. |

||||||

|

Three days later on 27 July, Vuillard notes both the purchase of a canvas and the name of the square with the little park where he has been sketching: the square de la Trinité. On 2 August Vuillard begins to despair over the slow progress being made on the Square: "Worthless morning, no work no ideas, atelier in disorder. I am before the big canvas nailed to the wall inert, without the will to think. Disorder in my brain... Truly, as decoration for an apartment, a subject that's objectively too precise would easily become insupportable. One would tire less quickly of a textile, of drawings without too much literary precision. Use a model to sustain one's imagination. The imagination always generalizes."25 But then on 7 August, Vuillard ends his journal entry on a more positive note: "Nevertheless, yesterday at the end of the day, facility for what little work was produced; thinking of the big canvas on the wall, envisage some subjects."26 Just below these lines, in a tiny pen and ink sketch, Vuillard draws the nursemaid and baby exactly as they will be pictured in the Square. Finally, two weeks later, on a page opposite a journal entry dated 21 August, Vuillard sketches a woman in a striped dress seen from behind and walking toward a woman in a plain dress coming in the other direction.27 This very vignette also appears unchanged in the center of the Square. |

||||||

| Though the preceding journal entries, as well as the dimensions and proportions of the Square, leave no doubt that it was originally destined to be the "grande toile" of The Public Gardens—that is, to fill the space ultimately occupied by Conversation (fig. 4)—as it turned out, Vuillard wisely decided against large, close figures for his cycle, and the picture was never to hang in the Alexandre Natanson salon. At some point, Square de la Trinité was sold to Alexandre's younger brother Thadée.28 | ||||||

| Chastel, in 1946, eloquently evoked the texture, colors and composition of the Square: "It is closely woven like a tapestry, and all is reduced to the gentle, reciprocal play of two grays, close in tone but different in origin, a rose and a lilac mauve, a bluish green and a restrained yellow, which the presence of flowers, benches and figures allows to be freely distributed. But all this is composed in the easy and graceful envelope of a finely sustained and very legible arabesque, which knots and returns the spiral in the fashion of the musical motive in pieces by Debussy that bear precisely this title."29 The Square's insistent arabesque winding in and out of depth in the form of a giant figure eight must have been, along with the arresting emphasis on the huge foreground figure, among the reasons for Vuillard's eventual decision to reject the picture; for these dominant compositional devices must have been seen by Vuillard to result in pictorial autonomy rather than fostering the continuity which would lead on the viewer exploring the whole large mural decoration—to progress from left to right, and on to the next panels. | ||||||

|

On 21 August Vuillard wrote in his journal: "Received the money from Alexandre. Canvas9m50 by 2m40, at 3,80=36,10. fixer 1,10. Indian ink 0,60. total 37f,80."30 This provides the terminus postquem for actual work on the definitive canvases, for which Vuillard has bought enough material to prepare the eight remaining Natanson panels. Opposite this entry, on the same page as the two women Vuillard incorporated into Square de la Trinité, are Vuillard's next ideas for The Public Gardens. Intended as pendants, the two studies, which are labelled "tapestries" by Vuillard, correspond to existing paintings. The sketch on the right is a first and still rough idea for Under the Trees (fig. 9), and the drawing to its left is an evolved study for a painting known as In the Tuileries (fig. 11).31 Vuillard's eventual elimination of In the Tuileries from his decorative cycle—it remained in his atelier until c. 1900—is probably the result of objections not unlike those that led to the replacement of Square de la Trinité (fig. 10). In the Tuileries draws the viewer into the picture along a diagonal axis running right to left and then only slightly reversed to right at the ramp; according to the preparatory sketches, this right-to-left impulse would have been reinforced by the foreground figures of the abutting panel at right. The panel's sense of deep spatial recession was to be balanced by an equally forceful return to the surface, now left to right, via the tree foliage painted in the upper portions of the two compositions. As in Square de la Trinité, the problem here lies with Vuillard's spatial manipulations. Derived from his easel paintings, these complicated backward and forward movements, involving one or more panels, repeatedly violate the integrity of the wall's surface while failing to generate progression rightwards. Vuillard seems to be learning, through a process of trial and error, that the experiments successfully carried out in his earlier decorations, especially the Desmarais Screen, are inappropriate to a large scale mural decoration; and that the Natanson's "tapestries" demand much more than the enlargement of one of his smaller pictures. | |||||

| On 10 September Vuillard wrote to Alexandre Natanson for more money, presumably to buy more canvas and supplies: "The panels are emerging from the fog and I am rather satisfied, but my expenses are exceeding what I thought, could you send me another hundred francs!"32 The same day Vuillard also devoted an entire entry in his journal to The Public Gardens.33 In the course of writing this crucial entry Vuillard reveals the overall guiding principle of his decoration: "Primary idea: twinkling decor of highly ornamental leaves. Not this or that particular sensation of nature, of trompe l'oeil, be wary of these." Earlier in the same entry, while reviewing the role that gradations of value are to play in his decorations, Vuillard also comes to a decision regarding his subjects. He briefly describes six of the Natanson panels: Conversation (fig. 4), Red Parasol (fig. 5), Promenade (fig. 6), First Steps (fig. 7), The Two Schoolboys (fig. 8), and Under the Trees (fig. 9). Therefore, by the 10th of September, at least in Vuillard's mind, Conversation (fig. 4) had taken the place of Square de la Trinité (fig. 10) and The Two Schoolboys (fig. 8) had taken the place originally to be held by In the Tuileries (fig. 11). This second substitution is confirmed by a pen and ink sketch in the Musée d'Orsay.34 In the lower right-hand corner of the sheet, Vuillard envisions The Two Schoolboys (fig. 8) and Under the Trees (fig. 9). Conceived as a single continuous composition, the two panels are dominated by a horizontal frieze of tree foliage that much reduces the impression of spatial recession associated with Vuillard's earlier project. Two other panels from The Public Gardens can be identified in the sketch: at left an advanced study for Promenade (fig. 6) beside an as yet tentative hint of First Steps (fig. 7), and third from the left, a highly developed, though at this stage reversed, study for Asking Questions (fig. 2), not mentioned in the 10 September journal entry.35 In the upper right-hand corner of the page Vuillard indicates the future placement of the panels in the Natanson Salon, identifying each of the nine pictures by noting its width in centimeters. On a second sheet now in the Yale University Art Gallery we find a drawing for one of the gamins, exactly as he will appear in The Two Schoolboys (fig. 8), and next to it an early idea for Nursemaids (fig. 3), also not included in the 10 September journal entry. Though this last composition will undergo changes, in particular the suppression of the little building, the drawing is the first to include Vuillard's all-important esplanade sun patches, one of the principal devices by which Vuillard will direct the progression through his decorations. | ||||||

|

Two sheets of pastel studies (Musée d'Orsay, Paris), originally part of a single large sheet of paper, show The Public Gardens in their definitive order.36 (The pastels for the first two scenes, Little Girls Playing [fig. 1] and Asking Questions [fig. 2] are actually on the verso, another confirmation that their inception was later than the other scenes.) A second, unpublished, plan for the Natanson salon in Vuillard's 1894 sketchbook confirms that Vuillard also planned dessus de porte as part of his decoration (Salomon Archives). (On the page he has written "dessus de porte 40 de haut, sur 1.63. ") These panels must have been intended to go over the door and the window indicated by Vuillard as being at the two ends of the room.37 We also learn from this sketch that a large mirror came between The Two Schoolboys (fig.8) and Under the Trees (fig. 9).38 Conversation (fig. 4), hanging on the opposite wall, would have been reflected in this mirror. On the basis of this plan we can determine the exact disposition of the panels: Little Girls Playing (fig. 1) and Asking Questions (fig. 2) to either side of the door with Little Girls Playing to the left of the door and Asking Questions to the right; then moving clockwise around the room the triptych Nursemaids (fig. 3), Conversation (fig. 4), and Red Parasol (fig. 5) on the second wall, then Promenade (fig. 6) and First Steps (fig. 7) on either side of the window39 on the next side, Promenade to the window's left and First Steps to its right, and finally The Two Schoolboys (fig. 8) and Under the Trees (fig. 9) to either side of the mirror on the fourth wall.40 |

||||||

|

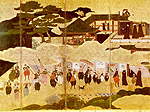

Vuillard's nine intricately interrelated and interdependent compositions constitute a rhythmic ensemble freed from the hierarchic order predominant in nineteenth-century mural decoration. In 1976, Perucchi-Petri made the tantalizing suggestion that Vuillard may have gotten the idea for his unorthodox ensemble from multiple-panel Japanese screens he could have seen at Paris dealers from the 1880s on.41 In her brief discussion, she does not propose any particular screen as a possible model. A celebrated Japanese folding screen, indeed one of the most famous works of Japanese painting not only in the Paris of 1894 but perhaps even to this day—and one that Vuillard is almost certain to have known intimately and must have scrutinized and pondered during the conception of this work—presents such striking affinities with The Public Gardens in composition, inscenation and decorative principles, that these can hardly be coincidental. This screen, known as the Paravent des Portugais (fig. 12) was first exhibited at the 1878 Exposition Universelle, where it attracted the attention of a writer especially admired by Vuillard, Edouard Duranty. Duranty discussed the screen at some length in his review of the exhibition for the Gazette des beaux-arts: "M. Guimet has brought back [from Japan] a very precious screen which allows us to establish the time periods in the making of Japanese art. The artist has represented a debarkation of the Portuguese, received by the Jesuits then established in the country. The Shogun Yeyas, persecutor of the Christians, some time later had the figures of the Jesuits scratched out. This screen is incontestably from the end of the sixteenth century, and it clarifies for us certain points of design such as it was then understood, and such as it had been practiced previously in Japan."42 In 1883, several years after the Exposition Universelle, Louis Gonse wrote of the screen in L'art japonais, his pioneering, fundamental survey of Japanese art reprinted first in 1886 and then again in 1891: "Among the monuments that can be dated to the late sixteenth century, without a doubt one of the most interesting to have come to Europe, is the folding screen exhibited in 1878 at the Trocadéro by M. Émile Guimet. It depicts the arrival of the Portuguese in Japan and their reception by the Jesuits. The figures are painted with great finesse…."43 |

||||||

| Still recognized by most scholars to be a late sixteenth or early seventeenth-century namban screen of the Kano school, the Paravent des Portugais was transferred with the rest of the Guimet collection to Paris in 1887 and has remained on view in the Musée Guimet since the museum opened its doors in November 1889. From the beginning a great favourite with the public, the folding screen was catalogued by L. de Milloué in 1883 for the first published guide to the Guimet collection: "Sixteenth-century screen representing the arrival of a Portuguese fleet in Japan. The admiral is received by the Jesuits. . . On the golden clouds, one sees the arms of the Mikado (the chrysanthemum) and those of the Shogun Taïko (the leaves and flowers of the paulownia) who governed Japan at the time of the arrival of the Portuguese."44 Vuillard was a frequent visitor to the Musée Guimet, whose didactic purposes and programs were in keeping with certain of the Nabis' own spiritual ambitions. For the Musée Guimet was not yet the French National Museum of Asian Art, but rather, in accordance with the expressed goals of Émile Guimet himself, a "museum of ideas" devoted to furthering the understanding of world religions.45 As a result, Guimet's remarkable library and extensive collection of religious documents were the central focus of the nineteenth-century Musée Guimet. Meanwhile, the oriental works of art from Guimet's collection were allocated to side galleries, where they were exhibited primarily to illustrate the spiritual cults of Japan and China. The Paravent des Portugais was installed with other historical, non-religious works in the Salle Impériale on the first floor. On July 23, 1894, that is the very day Vuillard began work on Le Square de la Trinité, Vuillard records in his journal having been to the Musée Guimet.46 That day, however, he notes having looked only at Japanese pottery on the ground floor. But, as Vuillard encountered problems with pictorial autonomy and the occidental spatial conceptions associated with his first panels for The Public Gardens, and as he came to the realization that these panels failed to establish visual planarity and generate the continuous decorative surface rhythms necessary to unify his cycle and lead the viewer from one panel on to another, he must have returned to the Musée Guimet in search of a solution to his growing dilemma. Between the middle of August, when Vuillard's crisis was at its most acute, and 10 September when he reveals in abbreviated terms the definitive program of The Public Gardens, Vuillard's journal is silent;47 but it must have been during these weeks, we speculate, that Vuillard discovered or more likely re-discovered the Paravent des Portugais and recognized in the screen the resolution of his crisis. | ||||||

| An initial cursory comparison between the six-panel folding screen (fig. 12) and The Public Gardens (figs. 1-9) discloses analogous exploitations of a high viewpoint, of linear rhythms, of contrasting light and dark patterns, of continuous asymmetrical composition, etc. A more careful examination, however, persuades us that Vuillard's highly idiosyncratic design has been—even more than at first might be thought—fully evolved from the Paravent des Portugais; his perceptions have been refocused through the lenses of modernist innovation in art, permeated with the temper of his time and place, and above all transmuted by the creative operations of his own burgeoning pictorial genius. The screen's ornate birds-eye-viewed body of water, which has been given an elaborately scalloped "shoreline" by intervening gold clouds, gently flows upward and to the right across the first two panels. Vuillard's stylized patch of sunlight, which also spreads diagonally "upward" over an esplanade in the first two panels of The Public Gardens (figs. 1-2), is an inverted, light-against-dark version of the screen's motif of black lacquer against gold. In Vuillard's plein-air adaptation of the screen, colored shadows cast by intervening though invisible trees (under which the artist has stationed himself and us), create the equivalent ornate outlines of his esplanade patches. These patterns are picked up and continued by visible background trees which have their homologues in the clouds seen at the top of the screen (fig. 13). Here Vuillard introduces his most fundamental and pervasive transposition of all, the transformation of the myriad, raised floral and foliate motifs that spangle the golden clouds of the folding screen into his "twinkling decor of highly ornamental leaves," "the primary idea," according to Vuillard, of his entire decorative scheme.48 There are further formal analogies to be found in details of the two decorations. For example, the tall slender tree seen at the extreme left in Girls Playing (fig. 1) recalls the ship mast in the first panel of the screen (fig. 13). The tree and the mast constitute the first important vertical accents in each of the two decorative ensembles. Similarly, the attitudes and costumes of the figures at the bottom of the second panel of the screen (fig. 14) have inspired the poses and spring apparel of the mother and children in Asking Questions (fig. 2) with the striped, gray-green and solid, rosy-peach colored pantaloons of the Portuguese men finding their counterparts in the dresses worn by the mother and her girls. | ||||||

| Moving on, we discover that the principle compositional features of Vuillard's triptych (figs. 3-5) have been derived from the lower half of the next three panels of the Japanese screen (fig. 15): Vuillard's wide, crescent-like arrangement of figures is adapted from the curved procession of Portuguese emissaries, his continuous picket fence behind the park visitors from the series of vertical struts seen along the palace facade, and once again Vuillard's background frieze of shimmering stylized leaves from the scintillating golden cloud of ornamental foliate motifs that hangs over the screen's procession. Moreover, a closer inspection of these respective panels reveals that Vuillard has wittily transposed formal scenes of a late sixteenth-century diplomatic mission into charming everyday vignettes of public garden life in late nineteenth-century Paris. The most humorous of these transpositions is the metamorphosis of the Portuguese admiral, dressed from head to foot in black with white piping and accompanied by attendants holding a red parasol and a leashed dog (fig. 16), into the seated old lady in Vuillard's Red Parasol (fig. 5), similarly dressed in black with white piping, holding a red parasol in her hand and the head of a small dog in her lap. Vuillard has even transferred the large white insignias that adorn the front of the admiral's costume to the old lady's hat. | ||||||

| For his last four panels of The Public Gardens (figs. 6-9), Vuillard has drawn inspiration from the upper portion of the last four panels of the folding screen (fig. 15). In Promenade (fig. 6) the two girls standing together in the foreground and the meandering sunlight patch call to mind the isolated pair of trees and the scalloped body of water, now more like a scalloped "tributary," seen in the third and fourth panels of the Japanese screen. In another charming touch, the gold against black cockerel finial with outstretched wings (fig. 17), seen in the fifth panel of the screen, is transformed into the little boy with arms spread wide outfitted in black against an undulating ocher path in Vuillard's First Steps (fig. 7). In the final panels of both series, the sinuous lines and graceful rhythms give way to a more geometrical, architectural organization. Here the dense, rigorously pollarded tree bowers of The Two Schoolboys (fig. 8) and Under the Trees (fig. 9) are an arboreal adaptation of the green tiled roofs of the open pavilion and covered walkways seen in the upper portions of the last two screen panels (fig. 18). The small, regular roof tiles find their equivalents in the now carefully ordered mosaic-like leaves of Vuillard's shaved chestnut and elm trees. The red trim of the roofs has become the turquoise border along the bottom edge of Vuillard's bowers. And now in the place of the converging perspective orthogonals employed by Vuillard in earlier sketches for his last panels, he introduces elements of Japanese perspective. The disposition of Vuillard's tree trunks along parallel diagonals derives from the arrangement of the wooden uprights that support the roofs depicted in the folding screen. Finally, the Parisian ladies seated in the shade of their natural, open air "pavilion" in Under the Trees (fig. 9), recall the figures seated and conversing on the floor of the Japanese pavilion (fig. 18), while in the distance Vuillard's women in black, who stroll along shady galleries, evoke the Jesuit priests proceeding along the covered walkways. | ||||||

| Vuillard's 1894 decoration constitutes an important, hitherto unrecognized chapter in the history of japonisme. Furthermore, with The Public Gardens, the impact of Japanese art on the evolution of Vuillard's formal and decorative language reaches its first point of culmination. But Vuillard's choice of the Paravent des Portugais as a model for The Public Gardens was governed by more than purely formal and decorative considerations. Vuillard realized that his choice of the Guimet Screen also offered him the opportunity to allude to, and in a sense even illustrate, a major historic and artistic development. For in his Public Gardens, Vuillard has adopted a rare, early Japanese screen that actually documents the first, tentative phase of contact between Japan and the West, as the prototype for a modern European decoration that ultimately, if covertly, demonstrates the far more decisive and consequential meeting of Japan and the Occident in the late nineteenth century. In other words, Vuillard is indirectly drawing a perceptive and instructive distinction between the superficial influence the Portuguese presence in Japan had on the traditions of the Kano school as witnessed in the Guimet screen—an impact essentially limited to a fascination with exotic Western dress and manners—on the one hand, and his own witty, modernist transpositions and profound assimilation of Japanese principles of composition and design in The Public Gardens, on the other. | ||||||

| * * * | ||||||

| Japanese models will continue to play a critical role in the conception of Vuillard's later Nabis decorations, especially those designed for Henri Vaquez (1896), Jean Schopfer (1897), and Adam Natanson (1899). Before undertaking these later decorative commissions, however, Vuillard finally came into direct contact with S. Bing, and under Bing's growing influence, Vuillard was persuaded to participate in the brilliant art dealer-entrepreneur's ambitious new program for the revival of the decorative arts. In May of 1894, Bing commissioned Vuillard, along with other of the Nabis, to design cloisonné Tiffany stained-glass windows, which were first exhibited at the Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts on the Champs-de-Mars in April 1895. The success of the Tiffany stained-glass windows led Bing to commission major multi-panel decorations from the Nabis for the inaugural exhibition at Art Nouveau, which opened in December 1895. Vuillard was given a small, model sitting room to decorate.49 The five panels Vuillard painted for Bing's Maison de l'Art Nouveau constitute what is generally considered one of Vuillard's masterpieces in the art of decoration. But, perhaps even more significantly, Bing's commissions afforded Vuillard and the Nabis an occasion to forge a group aesthetic through what appears to have been Bing's insistence that the artists' works, however diverse, share a dominant abstract formal feature: cloisonnisme in the Tiffany stained-glass windows and, appropriately, the linear arabesque at the Maison de l'Art Nouveau. Never before or after Bing's direct intervention, were the original aspirations of the Nabis brotherhood given such harmonious and unified expression. | ||||||

|

All translations are by the authors, unless otherwise noted. 1. See Gabriel P. Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing: Paris Style 1900 (New York and Washington: Harry N. Abrams and the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, 1986), 25-28. 2. Ibid., 28-29. 3. "Exposition de la gravure japonaise," Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Paris, 25 April-22 May 1890. See Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing, 29-31. 4. Ursula Perucchi-Petri, Die Nabis und Japan: Das Frühwerk von Bonnard, Vuillard und Denis (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 1976), 215 n. 283 details the contents of Vuillard's Oriental art collection as follows: 2 statuettes-a seated woman and seated man; 10 flower paintings-pen and ink, watercolor on silk; 6 illustrated albums, including Karsushika Hokusai's Manga (vol. 6), and Kitao Masayoshi's Ryakuga Shiki; woodblocks by Utagawa Hiroshige, Suzuki Harunobu and others. In 1990, a collection of 180 Japanese wood-block prints belonging to Vuillard was discovered in the Salomon Archives, Paris. Twelve of Vuillard's ukiyo-e prints were exhibited in the 1993 Nabis exhibition. For color reproductions of four of these prints, see Ursula Perucchi-Petri, "Les Nabis et le japonisme," in Nabis 1888-1900. Exh. cat. Zurich: Kunsthaus and Paris: Grand Palais (Paris: Editions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1993), 36-fig. 5, 38-fig. 9, 44-fig. 18, 53-fig. 28. 5. John Russell, "The Vocation of Edouard Vuillard," in Edouard Vuillard, 1868-1940. Exh. cat. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario (London: Thames and Hudson, 1971), 29, cat. nos. 15-25. For illustrations in color, see Patricia Eckert Boyer, ed. The Nabis and the Parisian Avant-Garde. Exh. cat. New Brunswick: Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum (New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press, 1988), col. Pls. 40-42. 6. Vuillard's collection included woodblock prints by the following artist: Anonymous (6), Eizan (3), Gekko (1), Hanzan (1), Hiroshige (77), Hokuba (1), Hokusai (4), Kunichika (4), Kunihiro (1), Kunimaro (1), Kunimasu (1), Kunisada (45), Kuniyasu (1), Kuniyoshi (15), Sadahide (3), Sadanobu (1), Shigeharu (3), Shigenobu (1), Toyohide (1), Toyokuni (1), Toyokuni II (2), Utamaro (3), Yoshitora (3), Yoshitoshi (1). 7. Antoine Salomon and Guy Cogeval, Vuillard: The Inexhaustible Glance. Critical Catalogue of Paintings and Pastels (Milan: Skira Editore and Wildenstein Institute Publications, 2003), 389-97, cat. no. II-104. 8. Salomon and Cogeval, Vuillard, cat. no. IV-78. 9. Perucchi-Petri, Die Nabis und Japan, 297-98. 10. See Salomon and Cogeval, Vuillard, cat. nos. V-28 and V-32. 11. Perucchi-Petri, Die Nabis und Japan, 119-20, 133-34. 12. Salomon and Cogeval, Vuillard, cat. no. V-39. 13. Perucchi-Petri, Die Nabis und Japan, 144. 14. For Vuillard's Public Gardens Cycle, see Claire Frèches-Thory, "'Jardins publics' de Vuillard," La revue du Louvre et des musées de France 29, no. 4 (1979): 305-12; Gloria Groom, Edouard Vuillard: Painter-Decorator. Patrons and Projects, 1892-1912 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993), 42-65. 15. Edouard Vuillard, Journal I:2, 12v, Institut de France (hereafter cited as Vuillard journal). 16. "Offer of a decoration, to do whatever I wish. Why not attempt it, why not want these vague desires, why not have confidence in these dreams which are, which will be realities for others as soon as I have given them a prior existence." Vuillard journal, Jan. 1894, I:2, 66r. 17. Vuillard journal, 16 July 1894, I:2, 44r. 18. Reproduced in Salomon and Cogeval, Vuillard, 394. 19. See sketch in Vuillard journal, 23 July 1894, I:2, 45r. 20. Reproduced in Salomon and Cogeval, Vuillard, 394. 21. Our discovery of a direct connection between Square de la Trinité and The Public Gardens, as well as the actual identity of the square—previously unknown—were published without our being credited by Guy Cogeval and Kimberly Jones, Edouard Vuillard. Exh. cat. Washington: National Gallery of Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 176 and Salomon and Cogeval, Vuillard, 387-88. Our findings were included in our manuscript, "Rediscovering Vuillard," copies of which have been on deposit in both the Salomon Archives and the Wildenstein Institute since May 1996. Our manuscript was copyrighted several months before the publication of either the Vuillard exhibition catalogue or the catalogue raisonné. 22. Vuillard journal, 23 July 1894, I:2, 45r. 23. Reproduced in Salomon and Cogeval, Vuillard, 388. 24. Vuillard journal, 24 July 1894, I:2, 45v. 25. Vuillard journal, 2 Aug. 1894, I:2, 47r-v. 26. Vuillard journal, 7 Aug. 1894, I:2, 48r. 27. Vuillard journal (after 30 Aug. 1894), I:2, 49r. Reproduced in Groom, Vuillard, 59. 28. Gloria Groom (Vuillard, 43-46) begins her chapter, "Women, Children and Public Parks," with Square de la Trinité, a picture which she separates from the The Public Gardens cycle and presents as a separate commission. According to Groom, Misia and Thadée Natanson, who married in 1893, commissioned the Square as a "kind of wedding gift to themselves." Groom, however, does not cite any evidence in support of her hypothesis. Indeed, she is perplexed by the painting's monumental scale. There are no known photographs or paintings showing the Square hanging in the Natanson rue Saint Florentin apartment. 29. André Chastel. Vuillard: 1868-1940 (Paris: Librairie Floury, 1946), 52-53. 30. Vuillard journal, 21 Aug. 1894, I:2, 48v. 31. Groom (Vuillard, 52, 58) was the first to recognize the connection between the sketch in Vuillard's journal and In the Tuileries. Groom errs, however, in re-titling the picture Au Luxembourg. We are in the Tuileries Gardens looking west toward the place de la Concorde. The ramp that appears in the picture is that in the northwest corner leading up to the Jeu de Paume (on the right). This error is repeated by Perucchi-Petri in Nabis 1888-1900, 337, cat. no. 168. 32. Vuillard to Alexandre Natanson, 10 September 1894, formerly Art Market. Location unknown. 33. This essential document of the rapidly coalescing program of the cycle already posits the themes of six of the nine panels:

Primary idea: twinkling decor of highly ornamental leaves. Not this or that particular sensation of nature, of trompe l'oeil, be wary of these" (Vuillard journal, 10 Sept. 1894, I:2, 50r.) 34. The Orsay pen and ink and pastel studies were published in Frèches-Thory, "Jardins publics," 308-10. For reproductions in color, see Groom, Vuillard, 60-61. 35. Reproduced in Groom, Vuillard, 53. 36. See note 34. 37. See Salomon and Cogeval, Vuillard, nos. V-39.10 and V-39.11 38. On another page of the 1894 sketchbook, Vuillard has indicated "38 + 1m62, dessus de porte. Cadre de la glace, 2,20 long h 2,04. " Salomon Archives, Paris. 39. On 16 December 1898, Vuillard took Signac and Théo van Rysselberghe to see three of his decorative cycles, chez Jean Schopfer, Dr. Henry Vaquez, and Alexandre Natanson. Upon seeing The Public Gardens Signac complained, "At the Natansons there are two decorative panels hung against the light, totally invisible, because he [Vuillard] failed to take into account the obscurity created by the luminous contrast of the window—and he limited himself to a range of colors that was too dark" (Cited in John Rewald, "Extraits du journal inédit de Paul Signac," Part 3, "1898-1899," Gazette des beaux-arts 42, nos. 1014-15 [July-Aug. 1953]: 36). 40. This installation of The Public Gardens was first proposed by Claire Frèches-Thory, "Jardins publics," 308. Curiously, however, Frèches-Thory believed that the cycle began with The Two Schoolboys and Under the Trees and not with Little Girls Playing and Asking Questions. 41. Perucchi-Petri, Die Nabis und Japan, 144. 42. Edmond Duranty, "L'Extrême Orient à l'Exposition Universelle," Gazette des beaux-arts 18 (Dec.1878): 1012-14. Excerpted and translated in Michael Komanecky, The Folding Image: Screens by Western Artists of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 1984), 49. 43. Louis Gonse, L'art japonais, vol. 1 (Paris: A Quantin, 1883), 208. 44. L. de Milloué, Catalogue du musée Guimet. Première partie: Inde, Chine et Japon (Lyon: Imprimerie Pitrat Ainé, 1883), 269. 45. Francis Macouin and Keiko Omoto, Quand le Japon s'ouvrit au monde (Paris: Gallimard/Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1990), 88-90. 46. The full entry reads "Musée Guimet poteries japonaises" (Vuillard journal, 23 July, 1894, I:2, 44v). Though Vuillard had not yet recognized the screen as a model for his decoration, this concurrence leaves no doubt that he was at the Musée Guimet in search of inspiration for his Public Gardens. 47. See note 33. The Musée Guimet remained open with regular hours during the entire summer. 48. See note 33. Milloué's 1890 guide to the Musée Guimet does not include an illustration of the Paravent des Portugais, but it does reproduce the arms of the Shogun Taïko, the very paulownia leaf and flower motif that pervades the clouds of the screen. 49. Annette Leduc Beaulieu and Brooks Beaulieu, "The Thadée Natanson Panels: A Vuillard Decoration for S. Bing's Maison de l'Art Nouveau," Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 1, no. 2 (Autumn 2002). Retrieved on 23 September 2003 from http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn_02/articles/beau.shtml.

|