American Art History Digitallysponsored by the Terra Foundation for American ArtWest on the Walls: The 1807 Exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

by Wendy Bellion, Lea C. Stephenson, and James Kelleher, with Allan McLeod and Kristen Nassif

Wendy Bellion is professor of art history and Sewell C. Biggs Chair in American Art at the University of Delaware, where she also serves as director of the Center for Material Culture Studies. Her research focuses on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century art and material culture in North America and the Atlantic World. Her major publications include Iconoclasm in New York: Revolution to Reenactment (Penn State University Press, 2019) and Citizen Spectator: Art, Illusion, and Visual Perception in Early National America (University of North Carolina Press, 2011), which was awarded the Charles Eldredge Prize by the Smithsonian American Art Museum. A forthcoming volume, Things Change: Material Cultures of the Mobile Eighteenth Century, coedited with Kristel Smentek, will be published by Bloomsbury Academic in 2023.

Email the author: wbellion[at]udel.edu

Lea C. Stephenson is a PhD candidate in art history at the University of Delaware. Her work focuses on late nineteenth-century American and British art, specifically the Gilded Age and the relationship between the senses, embodiment, and portraiture. Her current projects explore late nineteenth-century Egyptomania and the relationship between American Orientalism and empire. She received her MA from the Williams College Graduate Program in the History of Art in 2017. Stephenson has also previously worked at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Preservation Society of Newport County, Dallas Museum of Art, and the Clark Art Institute.

Email the author: lcsteph[at]udel.edu

James Kelleher is an architectural historian and museum professional specializing in the seventeenth through early nineteenth centuries. He received his master’s degree from the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture, where his thesis focused on domestic architecture in southeastern Massachusetts from 1650 to 1720. His research interests include the persistence of English traditions in Colonial American building, the intersections of architecture and social life, and local variations in building practices.

Email the author: j.ian.kelleher[at]gmail.com

Citation: Wendy Bellion, Lea C. Stephenson, and James Kelleher, with Allan McLeod and Kristen Nassif, “West on the Walls: The 1807 Exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 21, no. 1 (Spring 2022), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2022.21.1.21.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Scholarly Article|Interactive Feature|Project Narrative

“We shall now feel the Pulse of the Citizens of Philada: with the effect of a grand Exhibition.”[1] So predicted Charles Willson Peale (fig. 1), artist and proprietor of the Philadelphia Museum, after hanging the first exhibition of paintings at the newly established Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in November 1807. The “grand exhibition” brought together about two dozen pictures created at home and abroad, and it succeeded in generating audiences and revenue for the nascent academy. In retrospect, it is tempting to try to identify in this moment the origin of a “new school” of US art, as the academy’s own champions tried to suggest. Yet our research and digital reconstruction of the exhibition reveals something else: the multiple interests—transatlantic and national, commercial as well as cultural—that materialized on the academy’s walls, and the many actors responsible for the exhibition.[2]

The core of the 1807 exhibition was a group of paintings sent from London to the United States by the American painter and inventor Robert Fulton. Three works derived from Shakespeare plays were the highlights of the collection: Benjamin West’s King Lear (1788) and Hamlet: Act IV, Scene V (Ophelia before the King and Queen) (1792), and his son Raphael West’s Oliver and Orlando (a scene from As You Like It; 1798). Fulton also lent five paintings by Dutch and Italian artists, and eleven history paintings by the British artist Robert Smirke that Fulton had commissioned for reproduction in The Columbiad (1807), an epic poem composed by his friend and patron, Joel Barlow.[3] To these works, Peale added his own portrait honoring the academy’s president, George Clymer, and another touting his family’s achievements: Rembrandt Peale’s portrait of Rubens Peale with a Geranium (1801). The exhibition also featured portraits of Benjamin West, Fulton, Barlow, and Fulton’s portrait of a fellow engineer, Charles Stanhope. Several paintings contributed by a local collector rounded out the exhibition.[4]

As one of the earliest public displays of paintings in the United States, the academy exhibition is of singular historical significance.[5] Moreover, it took place in the first building specially constructed to display art in the new republic, located on the north side of Chestnut Street between Tenth and Eleventh Streets. Any effort to understand the exhibition, however, must reckon with a fundamental absence: the original structure, designed by the amateur architect John Dorsey, was largely destroyed by fire in 1845. (The present academy building on Broad Street, designed by Frank Furness and George H. Hewitt, opened in 1876.) Fortunately, Peale documented the steps he took to prepare and hang the exhibition in several letters to Fulton, one of which included a sketch of the nearly completed installation (fig. 2). Annotated with notes and a legend, it is a rare document of an ephemeral exhibition and a precious survival from a formative period in the academy’s history.

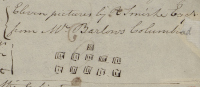

Fig. 2, Charles Willson Peale’s sketch of the 1807 installation, from Charles Willson Peale to Robert Fulton, November 15, 1807. Pen and ink on paper. Peale-Sellers Papers, letterbook 8, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia. Photograph courtesy of the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia.

This article draws on Peale’s letters and sketch, together with related primary sources, to analyze the 1807 installation and to partially reconstruct it in interactive digital formats.[6] We revisit—and offer new renderings of—the exhibition room itself, examining Peale’s decisions about how and where to place the paintings. Composed primarily of a circular gallery and crowned by a neoclassical dome, the room followed the model of rotundas in new municipal buildings in Philadelphia. Plans, elevations, and a three-dimensional model of the academy, commissioned for this article, represent this interior for the first time and demonstrate the difficulties it presented to Peale, who encountered practical obstacles when hanging the paintings, including the largest works in Fulton’s collection: Benjamin West’s pictures.

The process of visualizing the exhibition digitally has led us to understand how numerous individuals and aspirations together shaped the exhibition. Leaders of the academy regularly extolled the future of US art in superlative terms. Fulton and Barlow expressed similar ambition in The Columbiad, in promotional literature for the exhibition, and in private correspondence. While Peale shared their optimism, he was guided by the practical imperatives of securing income to expand the academy and the challenges of hanging pictures in a gallery designed for displaying sculptural casts, not paintings. We argue that these varied concerns coalesced in the exhibition room and help to explain the appearance of the installation. While Peale thought carefully and creatively about how to hang the paintings, drawing on period exhibition practices, his plan did not represent what we might today call a curatorial vision. Nor did the diverse assemblage of European and local paintings succeed in visualizing an emerging national aesthetic, as academy supporters had intended. Instead, the exhibition registered the extent to which, at this decisive moment in the establishment of a new art school and exhibition space, US art remained tethered to broader Atlantic networks of culture, patronage, and circulation.

We also demonstrate how the exhibition manifested the particular interests of Fulton and Peale. Fulton aimed to promote Barlow’s The Columbiad, a triumphant celebration of US culture. Peale sought a permanent home for his Philadelphia Museum. Together, they anticipated that the prominent display of West’s paintings would encourage the academy to purchase Fulton’s collection, motivate Philadelphians to financially support the institution, and thereby enable the academy to add new rooms for galleries and drawing instruction. Peale’s sketch of the installation reveals how he gave prominence to certain works of art, such as the West and Smirke paintings, and clustered others in groups—namely portraits of West, Fulton, and his son Rubens—in advance of these objectives. The 1807 exhibition thereby materialized hopes and ideas that are otherwise only registered in disparate textual sources.

At this point, it is crucial to acknowledge that neither Peale’s sketch nor our digital reconstructions offer a complete record of the installation. Peale’s annotations, for instance, indicate that he did not know who had created some of the European pictures: “Who Painted Abel? Titian or Poussan?” he asked Fulton. “Who painted Adam & Eve? Rubens?”[7] His notes also document the progress of an installation that was still in formation. Beneath a square labeled “Abel,” Peale scribbled, “space left to put others which I shall place tomorrow.” This brief inscription indicates that, although most of the paintings were installed by the time Peale made his sketch of the wall, others remained to be hung the following day. Although published accounts of the exhibition give titles for these works and name the presumed artists, they do not indicate where the pictures appeared on the walls.

Following best practices for digital scholarship, our project acknowledges these gaps in the historical record.[8] We call attention in the digital components to features that remain unresolved or speculative. Prints after unlocated or unidentified paintings, for example, serve as placeholders instead of substitutes and are explicitly designated as such. Where it has been necessary to make informed conjectures about the appearance of the exhibition room, we relied on period sources that Peale, Dorsey, and their contemporaries might have accessed, such as the wall colors of the rotunda in the Bank of Pennsylvania, one of Dorsey’s design sources for the academy building. In sum, our goal is to offer a partial digitization and explanation of Peale’s sketch and the material space of the 1807 exhibition. We explore what these resources make visible about the academy installation instead of attempting complete reconstructions, conceding the limits of our historical knowledge. We hope more evidence will come to light over time that will allow this resource to continue growing.

The Pennsylvania Academy

Founded in June 1805, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts was the city’s second effort to develop a local school for art education and exhibition. Peale had helped lead the first attempt: the short-lived Columbianum Academy, which produced just one exhibition in 1795. His efforts followed on the success of his Philadelphia Museum (also known as Peale’s Museum), which had rapidly grown into a sizable collection of paintings and natural history specimens following its establishment in the 1780s. The museum was the first public institution of its kind in the United States. It was a key attraction for visitors to the city, and luminaries including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson regularly made donations of objects. Yet, as proprietor of the museum, Peale worked constantly to secure funding and allies.[9] When he joined the academy as one of twelve directors, he readily offered to host meetings at the museum, sensing, no doubt, a common purpose between the two organizations. He confided his hopes to his daughter Angelica, trusting the fine arts would “meet with greater encouragement in this life than heretofore, as is evidenced by the spirit with which the Citizens have began a subscription.”[10] One friend, the architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, was glad to learn that the founders, mainly lawyers and businessmen, had “come forward with that most essential support of all Art Money,” though he teased they had little “taste for, or knowledge for any Arts but that of bookkeeping or cookery.”[11]

Even at this formative stage, Peale was thinking big. “The proposal,” he explained to his son Raphaelle, “is to import Casts and begin a Gallery of figures and Paintings; beginning with an exhibition—To receive paintings that may be offered for sale and if sold to take a commission on such sale . . . This is the first part of the plan—out of this will arise the Academy of drawing from the Models and afterwards from the life—.”[12] Peale’s remark underscores the practical needs and concerns that informed his leadership and planning: the academy would ideally double as a space for selling art, with the goal of raising capital to fund drawing instruction, including life classes.

Benjamin West also figured centrally in the academy’s planning. West, a Pennsylvania native, was among the few colonial artists to achieve international recognition overseas. Following several years of studying classical art and architecture in Italy during the 1760s, he established himself as a painter in London, revolutionizing the practice of history painting by introducing contemporary events, characters, and costumes into narrative art. He attracted the attention of the royal court as well as the devotion of Anglo-American artists who followed him abroad. Back home, newspapers lauded his success; together with John Singleton Copley and the waxwork sculptor Patience Wright, West was proof that artists born in the North American colonies could succeed on the cosmopolitan stage of London.[13]

Peale, who figured among the aspiring painters who sought training in London, hoped that West’s work would become the foundation of a permanent collection at the academy. He relayed a report from another son, Rembrandt, who had recently seen West in London, to President Thomas Jefferson, claiming that West was “very anxious to have all his designs, the originals of his historical paintings placed here . . . he had long contemplated and indeed preserved his works for this purpose.”[14] Peale’s academy colleagues recognized the significance of a public association with West, who in 1792 had become the president of the Royal Academy of Arts, and they elected him an honorary member at one of their first meetings.[15] Over the years to come, Peale and Fulton would continually—but unsuccessfully—urge the academy to purchase West’s paintings, using the 1807 exhibition as one of several vehicles of encouragement.

Initially, though, the academy proved more enthusiastic about acquiring sculptures than paintings. By February 1806, some four dozen plaster casts of classical statues and busts had arrived from Paris. Nicholas Biddle, a prominent Philadelphian and secretary to the US ambassador to France, had arranged for their purchase at the request of Peale and other academy directors. The shipment included casts of canonical works such as the Laocoön, the Diana of Versailles, and the Belvedere Torso—all reproduced, Biddle assured the academy, from the “great models of the Louvre.”[16] Peale prepared for their display by hiring craftspeople to construct wall brackets and pedestals, the latter outfitted with casters to wheel the heavy casts across a gallery floor.[17]

But first he needed an exhibition room.

The Dorsey Building

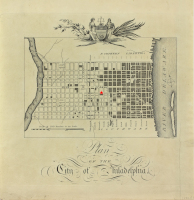

Peale and his fellow directors moved rapidly to establish the academy’s physical presence within the city. Raising subscriptions to finance construction of a building, they acquired lots located at the western edge of the city’s settlement yet convenient to the busy commercial and maritime centers along the Delaware River (fig. 3). On August 9, just two months after convening to establish the academy, a building committee publicly solicited bids for designs, requesting plans and elevations for a structure “45 feet front, 70 deep; the light of the principal room to enter from above and central, and the building to be so calculated as to admit hereafter of extensions on each side.”[18]

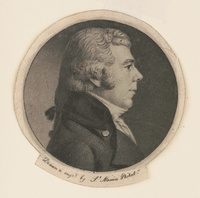

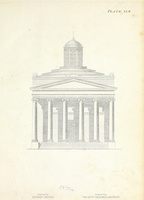

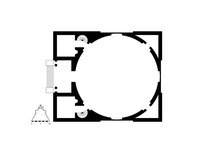

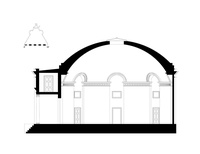

This account reveals that the building committee clearly had particular ideas in mind and, in fact, plans had already been drawn up by one of the committee members, John Dorsey, who counted architecture among his many interests and occupations (fig. 4).[19] Dorsey’s design for the façade projected a two-story elevation and a shallow dome, while the interior emphasized the exhibition room, “a compleat hemisphere concave springing out 10 feet from the floor,” forty feet in diameter and illuminated by a skylight (fig. 5). The plan set a circle within a rectangle, thereby creating space for corner rooms to either side of the southern entryway: a “Directors Room” and a “Lodge,” presumably spaces for the academy’s leaders and an intended keeper of the collections. A “Contributors Room,” possibly a lounge for subscribers, was to be located at the rear. Thin walls to the east and west sides of the exhibition room denoted areas where rooms could later be added to the structure. Stairwells, marked by icons resembling bicycle spokes, provided access to a basement as well as a “Gallery” that Dorsey aspired to include above “the Round room” (it did not feature in the completed building).[20]

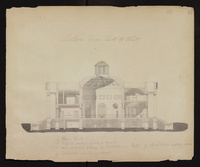

Work on the building proceeded rapidly. In September, Peale described the engineering and confirmed the basic contours of Dorsey’s design with a rudimentary sketch (fig. 6). The dome—a “cimi-circle, lighted from a Turret”—was to be made of brick. Peale worried it would be “rather difficult in execution” and require “some covering to keep rain from passing through the bricks, such as tiles, lead, Iron or wood—all of which are expensive, and therefore but illy agreeing with our funds, which although handsome yet not sufficient without a great increase of Subscribers.”[21] The exhibition room had already grown to an expected diameter of forty-five feet. It “will be handsome,” Peale assured Jefferson. (He added, for good measure, “I think it my duty to mention to you our want of funds to finish this Building.”)[22] Peale kept an eye on construction, managing labor and materials for the exhibition room and, increasingly, he complained about Dorsey. “The Building has been an expensive one,” he groused as work progressed. “I may be mistaken but I cannot help thinking less magnificent and more useful would have served it instead.”[23]

Yet magnificence was exactly what local enthusiasts perceived after the academy opened its doors in spring 1807. “Our builders and other mechanics, and every class of men may find something here to please and instruct,” a writer for the Port Folio avowed in 1809.[24] The minimalist structure and its pastoral setting also attracted attention from artists, including a print that complemented the Port Folio’s extensive description of both the exterior and interior. Benjamin Tanner’s engraving (after a drawing by John James Barralet; fig. 7) shows a broad flight of steps leading to a recessed porch, ten feet deep and framed by slender columns, that the Port Folio called “modern Ionic.” Above the lintel, a bald eagle grasped a palette and paintbrushes in its talons, symbolizing the academy’s coupling of national and artistic encouragement.[25] Flat-fronted bays at each side, punctuated only by small windows, epitomized contemporary tastes for plainness and symmetry. Atop, the graceful dome signaled the popularity of a classical form that was becoming omnipresent in new public and private construction.

Dorsey undoubtedly looked to nearby buildings by Latrobe for models. Scholars have underscored the stylistic resemblance, for example, between the façade of Dorsey’s academy and Latrobe’s Centre Square Engine House, which enjoyed celebrity as an aesthetic and technological wonder following its completion in 1801.[26] Dorsey’s circular exhibition room also recalled another nearby building: Latrobe’s Bank of Pennsylvania (1798–1801; demolished 1867). Famously, the bank’s front elevation conjured a Greek temple; among its fans was Owen Biddle, the master builder who led the academy’s construction until his untimely death in 1806 (fig. 8). A rotunda composed the bank’s core, measuring forty-five feet wide and sixty feet high (fig. 9). While not the first rotunda built in the early US, it was widely regarded as the most influential, catalyzing the construction of similar forms in cities from New York to New Orleans. Its effect—spacious and naturally illuminated—was sublime, according to both contemporaries and historians.[27]

In general shape as well as decorative particulars, Dorsey’s academy adapted elements of Latrobe’s signature Philadelphia buildings. But a key detail differentiated the two architects’ rotundas: whereas Latrobe’s bank space measured forty-five feet in diameter, the final measurement of Dorsey’s exhibition room went one foot farther, for a total of forty-six feet. Dorsey literally one-upped his accomplished peer. This was surely one of the factors that led Latrobe to criticize Dorsey repeatedly in his private correspondence.[28]

The most extensive source regarding the appearance of the exhibition room, including its dimensions, is the Port Folio’s “Description of the Building” from 1809. The essay presents a detailed account of the architectural program for a structure destroyed long ago. It chronicles design alterations, such as the distance from the floor to the base of the dome (the “springing of the ceiling”), that were introduced between the time of Dorsey’s conception in 1805 and the building’s completion in 1807:

The interior consists of a principal room, two committee-rooms, three chambers, and complete cellars under the whole. The principal room is forty-six feet in diameter and eighteen feet high to the springing of the ceiling, which is a dome having the sole light from its centre: the ceiling is plain except a radii of light in stucco around the opening and semi-circular architraves with reversed mouldings at the springing. The sides consist of eight tall pedestals alternating with an equal number of recesses which open to stair-ways or intended additional rooms; these recesses also consist of principal and attic pannels or openings; over these are arches whose saffits obtrude into the dome, the effect of which is novel; so that the dome appears (as it really does) to rest on those heightened pedestals, which have their full order of entablature occasionally relieved by guiloche enrichments.[29]

This description has provided us with the fullest source for developing visualizations of the academy’s interior and exterior, which are further explained in our project narrative (figs. 10–12).

Additional documents allow us to reimagine the exhibition room as a colorful space. Drafts for payments to workmen indicate that the plaster walls were painted in distemper; the pedestals and brackets, which supported casts and busts, were painted in oil. Although these papers do not describe the paint colors, it is possible that the color scheme mimicked the popular Adamesque appearance of the Bank of Pennsylvania rotunda. There, Latrobe had directed walls to be painted “a pale, but warm Oker, or straw color,” with inset panels in paler yellow and moldings in white. A white frieze was to be animated with light blue, while “dark rust” on a decorative fret would evoke a “Greek method of painting.”[30] In the absence of documents verifying the academy’s paint colors, we have drawn on Latrobe’s preferences for the main walls, panels, and moldings in our three-dimensional Blender digital reconstruction to offer an informed conjecture of the exhibition room’s appearance.

One thing is certain: there was a lot of green in the gallery. A “green cloth” covered the floor, according to one admirer of the “elegant circular room.”[31] This was likely a large piece of green baize, a felt-like fabric often used on the walls of early national galleries. Peale also ordered a large center table to be painted green and, when installing Fulton’s pictures in November 1807, he split the large exhibition room in half with an enormous curtain of green baize.[32] The curtain functioned like a wall, restricting visitors to just one half of the space.

By March 1807, with many of these preparations in place, Peale was able to declare the room “almost ready for Exhibition.”[33] In April, the academy opened to the public with the classical casts installed in the rotunda. The academy’s supporters quickly championed the new institution in lofty rhetoric that promoted a bright future. “Already we see many an American genius worshipping with an artist’s ardour at the feet of the Venus de Medici and at the shrine of the Apollo Belvedere,” the Port Folio crowed. George Clymer’s inaugural address, printed in the same issue, likewise called attention to the casts and architecture: “contemplation of the pieces of exquisite workmanship that encircle you,” he told the assembled guests, would stoke admiration and motivate young artists.

Clymer’s evocation of objects that “encircle” the viewers reminds us that Dorsey built the exhibition room to display sculpture, not paintings. Whereas the distribution of the casts in the circular gallery held the attention of visitors in the middle of the space, Peale’s installation of pictures, by contrast, would turn all eyes toward the walls—an experience that the space was not designed to cultivate.

And, while there were not yet any pictures there to look at, Clymer nevertheless invoked the name of Benjamin West to demonstrate what the academy’s cultivation of a native “bud or germ” might yield for the future of art in the US.[34] In so doing, he appealed to Philadelphia’s hometown hero, the celebrated West, as well as the patron who sought to bring his work stateside: Robert Fulton.

Robert Fulton, Joel Barlow, and Benjamin West

Fulton, a hopeful painter turned engineer, began laying the groundwork for the 1807 exhibition soon after learning about the founding of the academy. West himself was instrumental in this process. In September 1805, as Carrie Rebora has noted in a pioneering article about Fulton’s collection, West recommended Fulton’s collection to the academy directors. By that date, Fulton had acquired West’s large Shakespeare paintings, which would figure prominently at the academy for almost a decade after their installation.[35]

The two men had a long association. Like West, Fulton was from Pennsylvania. In 1786 he sailed to England to train with the older artist. Although Fulton publicly exhibited several history paintings in London, his interests soon drifted toward inventing. By 1805 he had developed or collaborated on the design of numerous technologies. The most famous was the steamboat Clermont, which made its inaugural voyage from New York City to Albany just three months before the academy exhibition.

Several influential patrons encouraged Fulton’s ingenuity, among them Joel Barlow and Charles Stanhope, a noted scientist and British earl.[36] Fulton painted portraits of each man, later sending both pictures to Philadelphia for the exhibition. Fulton and Barlow developed a close personal and working relationship during the many years they lived abroad in England and France. Barlow wore many hats: a diplomat and political radical, he was also a writer, best known for penning the epic poem The Vision of Columbus (1787).[37] In this work and other projects, Barlow encouraged the development of North American arts. On one occasion, he devised a pointed prompt for a prospective essay competition: “What are the practicable means of rendering the cultivation of the fine arts in America the most beneficial to political liberty?”[38]

Over time, Barlow also developed plans for a “National Institution,” a federally funded university to be housed in Washington, DC. Significantly, it was to include an art museum and art school. Barlow’s model was the Louvre—supported, notably, by the French government—and its “vast gallery of pictures.”[39] Though his proposal for a National Institution was only briefly entertained by the US Congress in 1806, it was widely reported in newspapers, and Barlow continued to advocate the project to Jefferson in December 1807—at the same time Philadelphians were encountering West’s art at the academy. “If . . . we could unite a system of public such as would grow out of a National Institution,” Barlow urged, “the whole would be dated from your administration and become one of its most lasting & splendid memorials.”[40] Jefferson was enthusiastic but did not press the case in Congress. Peale, on the other hand, who was determined to find a permanent home for the Philadelphia Museum, avidly followed Barlow’s plan, as we discuss below.

Barlow returned to the US in 1805, settling temporarily in Philadelphia before relocating to Washington, DC. Fulton remained awhile in London to advance a venture that would bear directly on Peale’s installation: the publication of The Columbiad (1807; fig. 13). The lengthy poem was thoroughly nationalistic in subject and tone. At 450 pages, it expanded Barlow’s earlier Vision of Columbus, which had located Christopher Columbus high atop a mountain, gazing across a panorama of the future United States. While the 1807 version celebrated numerous citizens of the US for achievements in politics, art, and science, Fulton’s presence was conspicuous from the opening dedication, where Barlow praised him for arranging the volume’s illustrations. Fulton had commissioned eleven canvases from the British history painter Robert Smirke, hired eight different engravers to create reproductions, and secured a printer in Philadelphia to publish the volume.[41] Barlow was delighted with the results, declaring the illustrations “elegant beyond example; no such fine engravings have ever been put into a book.”[42] Before Fulton sailed home to the US, he entrusted the plates to West.[43]

Fulton’s relationship with West extended to his role as art patron. While assisting with the production of The Columbiad, Fulton purchased three paintings by Benjamin and Raphael West from the auction of John Boydell’s famed Shakespeare Gallery, which pressed painting into the service of English identity formation. Boydell had hoped to foster a national school of painting, building on the reputation of England’s best-known writer.[44] West’s paintings figured centrally in these efforts, especially King Lear (fig. 14). At eight and a half by twelve feet, it was one of Boydell’s largest canvases, and one of the most expensive.[45] West represented a famous scene in the play, when Lear wanders wildly across a heath in the midst of a raging storm. West’s depiction from Hamlet pictured another character’s descent into emotional distress: Ophelia, scattering flowers before the royal court (fig. 15). The paintings reached a wide audience. At his London gallery, Boydell prominently displayed Lear over a door in the first room (fig. 16), and he reproduced both paintings as engravings in a folio published in 1803.[46]

In London and Philadelphia, Lear enjoyed greater celebrity than Ophelia, thanks in part to a vivid description in The Columbiad: “Lear stalks long with woes, the gods defies / Insults the tempest and outstorms the skies.”[47] Such adulation implicitly served Fulton’s goal of urging the academy to purchase West’s paintings. At the same time, it worked to generate excitement for the painting’s arrival in Philadelphia. Local publication of The Columbiad preceded the academy exhibition by just several months and, notably, the poem never acknowledged the painting’s origins at the Boydell Gallery. Instead, it restyled the picture as a North American production, a creation equal in nationalist import to the contributions of founders like Franklin and Jefferson. Through this rhetorical maneuver, a work of art made for an English national project was repurposed for the needs of the emerging US. Barlow and Fulton’s recontextualization never acknowledged that West had painted Lear to honor Britain’s literary past. Rather, their intent was prescriptive: to restyle the painting, a vibrant depiction of passion and power, as a catalyst for contemporary art in Philadelphia and a means to position West as the artist to lead the way forward.

As Fulton prepared to crate his collection for shipment across the Atlantic to the academy, he asked West to retouch his canvases; “they are charming,” he told Barlow in autumn 1806. He intended to eventually give his wife “the Smirkes for her Boudoir.” Fulton was uneasy, though, about the risks of oceanic transport on the winter seas. He sealed his will and his engineering drawings in a tin cylinder, asking Barlow to publish them “in a handsome manner” should his ship go down.[48]

Fulton issued a simpler request to Peale regarding the paintings: “you will get them up in the galary when how you think proper; I Shall be happy to hear how you proceed.”[49] Peale obliged, reporting his progress in a series of invaluable letters.

Preparing the Exhibition Room

Following the safe arrival of Fulton’s paintings in October 1807, Peale’s thoughts returned to how the academy could benefit from West’s celebrity. Anxious to “see Mr. West’s pictures belonging to Fulton at this moment in Stores of the Custom-House,” Peale shared his expectations with his friend John Isaac Hawkins:

Mr. Fulton has consented to have them exhibited in our Academy of the fine Arts for one year, and I have no doubt that it will give such an increase to the Income of that Institution as will enable us to open a School in the next Season for drawing from the living figure, and also to have Rooms to receive paintings for sale, thereby obtaining a certain pr. Centum to help the funds of the Institution, besides what [we] may get by an annual Exhibition of the works of living artists. The Building . . . is now finished, and a collection of Casts of Statues which we obtained from Paris, is displayed in a circular Room of 45 diameter lighted from the centre of the Dome, It is hansome, as indeed it ought to be, for it has cost a great deal of money before it could be opened to receive visitors. The additional Rooms above hinted at, I hope will be erected at half the expence of this first building. By these exertions to form exhibitions of Pictures, we shall be able to judge whether the desire to encourage the fine arts will raise the means to purchase Mr. Wests collection of historical paintings. If the exhibition of such should raise an Interest of 6 pr. Cent, on the cost which Mr. West may put on the pictures, then a company might be formed to make the purchase, more especially if the payments were to be made by installments, I shall be better to judge on this subject after Mr. Fulton’s Pictures have been seen by the Public.[50]

For Peale, the exhibition was a test of public enthusiasm as well as a fundraising initiative: if successful, it would enable the academy to add more galleries for displaying pictures, which in turn would yield the income to purchase history paintings by West. His comment underscores his continuing attention to practicalities; where Barlow and Fulton sought to celebrate and promote US achievements in the arts, Peale remained focused on attracting an audience to the new academy, raising income to purchase West’s paintings, introducing life classes, and expanding the building to include new exhibition rooms.

Peale’s correspondence over the succeeding weeks narrates the steps he took to realize these ambitions. From the Customs House, he retrieved more than a dozen boxes containing paintings by Fulton, Smirke, and the Wests, and arranged payment for storage, porterage, and duties. The largest pictures had arrived unframed and rolled. Peale stretched the three West canvases and tasked his son Rembrandt with repairing Lear. “The vernish sticking brought the paint away,” Peale reported in a long letter to Fulton, “but fortunately not on the figures.”[51]

Peale’s letter also reveals that he first experimented with arranging the collection on the east side of the circular exhibition room. He considered ways to nudge viewers closer to the walls, effectively shrinking the wide space of the rotunda: he removed part of a long table in the center, hung baize curtains from stanchions placed to the north and south of the table, and placed most of the casts and busts behind the fabric. “Tomorrow I expect to put the large Pictures, about 4, 5, or 6 feet from the floor, inclining a little forward, and hanging Smirk’s pieces beneath Mr. Wests pictures. these will nearly occupy from Door to Door (there being 5 doors in the Room) Raphaelle West’s between the big door & little door communicating to the Keeper’s room.”[52]

This important document conveys details about the architecture that our project team member, James Kelleher, has incorporated into his drawings of the interior (figs. 11–12): namely, the doors, five in total (one of which was the front door), and (following the cardinal orientations implied by Peale) a room for the academy’s keeper in the southeast corner. Peale’s account also illuminates the experience he hoped to create for viewers: he wanted to focus attention on the paintings by moving the casts out of view and to install West’s Shakespearean paintings at eye level, somewhere between four and six feet from the floor. The latter point reveals that Peale was following the Salon-style practice, familiar to exhibition-goers in Britain and Europe, of locating prized pictures “on the line.”[53] The forward tilt he anticipated may have been considerable, for the sheer physics of hanging rectangular paintings on curved walls would have prevented the framed pictures from lying flat.

For reasons Peale did not explain, he ultimately flipped the orientation of his installation, relocating the paintings to the west side of the rotunda.[54] Visitors would enter the exhibition from the south through the “Front Door” (designated at left in Peale’s drawing), then circumnavigate the western half of the room until they reached a perimeter marked by the baize curtain. Peale annotated the left and right margins of his sketch with the words “Baize” and “G Baize” (meaning “Green Baize”), adding vertical lines to evoke the folds of the cloth. He described its function to Fulton: “the Baise curtain 6 feet high supported by stanchions on the east outside of the Table to give distance for viewing the Paintings.” The curtain bisected the room like a wall, limiting viewers’ access to just one part of the rotunda. Presumably Peale moved the cast collection behind it, consistent with his earlier plans. The prescribed viewing distance was therefore limited to half the diameter of the forty-six-foot room: in other words, a maximum distance of twenty-three feet from the center to the principal area where Lear and Ophelia appeared.[55]

The stage was set. Peale prepared to take “the Pulse of the Citizens of Philada: with the effect of a grand Exhibition.”

The Academy Exhibition

It is safe to assume that Peale was responsible for the design of the installation. “The Pictures look admirably well as we have placed them,” he told Fulton. “Perhaps I can give you some Idea of their order by the following sketch.”[56] His drawing allows us to reconstruct much, if not all, of the order in which visitors saw the pictures; Fulton tendered an alternative idea for hanging the Smirke paintings that Peale may or may not have followed, as we note below. Nevertheless, the sketch permits us to assess how the works functioned as an ensemble and to understand how Peale grouped certain paintings to align himself with the transatlantic networks that Fulton had developed through his collaborations with Barlow, Smirke, and West.[57] It also serves as the basis for our 3-D digital reconstruction, which visualizes the gallery interior and the placement of known works at the exhibition (fig. 17).

Fig. 17, James Kelleher, Three-dimensional reconstruction of the 1807 Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts exhibition, 2021. Drawing created in AutoCAD 2019, rendering created in Blender (version 2.9). Courtesy of James Kelleher. Displayed using Pannellum.js.

Instructions:

Click or tap the panorama, hold down, and use your mouse, touchpad, or touch screen to scan.

Double click on each painting in the panorama to enlarge.

Click to view/hide information hotspots for each painting in the panorama.

At the academy, one of the first paintings that viewers encountered on their left as they entered the front doors was Antonio Balestra’s sizable Death of Abel (ca. 1701–4; fig. 18; now in the collection of the David Owsley Museum of Art, Ball State University, Muncie). The biblical scene would have made for a dramatic introduction to the exhibition. Italian paintings and religious subjects were equally rare in the few public exhibition spaces that existed in early nineteenth-century Philadelphia, such as Peale’s Museum. Early national spectators were accustomed to seeing portraits and, to a lesser degree, other artistic genres, including landscapes, still lifes, and genre paintings. As a history painting, Balestra’s work was therefore a rarity. So was the composition: Abel appeared as a half-nude figure, contorted yet sensual, splayed across a violent landscape of broken tree limbs. For viewers who had only encountered such figural dynamism in the bodies of sculptural casts, Balestra’s colorful work offered an exciting surprise.

Beneath the corresponding square labeled “Abel” in his sketch, Peale wrote, “space left to put others which I shall place tomorrow.”[58] This gap is where he may have located at least six paintings that are absent from his sketch but described by Fulton in a promotional account that appeared in Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser and other publications.[59] Two of these missing paintings were portraits: Fulton’s own paintings of Charles Stanhope (unlocated) and Joel Barlow (1805; fig. 19), which Fulton had painted as the basis for a frontispiece in The Columbiad.[60] Fulton’s inclusion of these portraits in his shipment to the academy highlighted his dual commitments to art and science as well as his personal connections to eminent patrons on both sides of the Atlantic.

The other works in this space may have included a painting of Adam and Eve now attributed to Antonio Molinari (ca. 1701–4; also in the collection of the David Owsley Museum of Art, Ball State University, Muncie), and three paintings by artists with last names suggestive of Netherlandish origin. These three works were mentioned in the Poulson’s account of the exhibition but remain unidentified and unlocated: The Flemish Boors by “Brower” (likely Adriaen Brouwer, 1605–38); The Slaughtered Bullock by “Ostade” (likely Adriaen van Ostade, 1610–85), described as “a very curious piece of still life”; and The Troubadour by “Skalkin” (possibly Godfried Schalcken, 1643–1706), which depicted a man playing a violin. (Fulton provided only last names for these artists; the works are further discussed in our interactive “Works Not Illustrated in Peale’s Sketch.”) An unspecified number of additional paintings were contributed by P. G. Lechleitner, a Dutch merchant in Philadelphia who was later appointed consul for the Netherlands. Lechleitner made his pictures available for purchase, perhaps hoping, like Peale, to help build the academy’s coffers.[61]

Significantly, then, visitors initially encountered a wall of European paintings at an academy that had been touted as advancing the future of art in the US. For some viewers, it may have seemed (not inaccurately) that American painting in 1807 remained grounded in European conventions and dependent on the transatlantic activity of art collecting. Others may have happily overlooked any mismatch between the academy’s rhetoric and the installation, however, because the exhibition was probably the first opportunity many Philadelphians had to view a concentration of Dutch and Italian pictures in a public space. Moreover, for a populace more accustomed to seeing portraits—which dominated artistic production in the early US—than biblical narratives and genre scenes, the diversity of artistic subjects would have also been a novelty. In this regard, the 1807 exhibition was prescient: when a new organization, the Society of Artists, began to hold annual exhibitions at the academy in 1811, a vast number of the hundreds of works displayed were attributed to European artists.[62]

The next cluster of pictures highlighted two individuals who had made the exhibition possible, Benjamin West and Robert Fulton. Over the southwest door of the room, Peale installed West’s portrait of himself in the act of painting a portrait of his wife (1806; fig. 20). On the wall to the right, he placed West’s portrait of Fulton elegantly disposed before a view of exploding torpedoes, one of Fulton’s inventions (1806; fig. 21). Each painting made the professions of the sitters immediately apparent to viewers. Together, they also visualized the patronage relationship between Fulton and West. Peale may have designed this pairing with the academy’s directors in mind, for it would have reminded them of Fulton’s desire to see West’s paintings acquired by the institution.

Peale may have intended another sort of promotion by hanging Rembrandt Peale’s portrait of Rubens Peale with a Geranium directly beneath Fulton’s portrait (“No. 13”; fig. 22). The painting was a joint demonstration of the talents of two of Peale’s many adult children: Rembrandt, who was achieving success as a portraitist, and Rubens, a naturalist who had taken on the responsibility of managing the Philadelphia Museum. The unusual composition depicted Rubens with a plant that he had cultivated—a geranium, the seeds of which had been acquired through Atlantic exchange by local botanists in the 1760s—and thereby signaled the family’s connections to cultures of art and science both within and beyond Philadelphia.[63] Peale’s location of this painting beneath those of Fulton and West visually anchored a trio of portraits. Somewhere nearby was Peale’s portrait of Barlow, and this was no coincidence: by creating a visual conversation among portraits of artists and patrons—and aligning his own family as part of it—Peale represented himself as part of a network of individuals who had declared visionary ambitions for the United States. His arrangement recalls the portraits of “worthies,” meaning accomplished individuals that Peale deemed worthy of emulation, that he installed together on the walls of his Philadelphia Museum following period conventions of portrait pantheons.[64]

In fact, during the spring months before the exhibition, Peale had already begun to align himself more closely with Fulton and Barlow by painting their portraits for his museum (1807; figs. 23–24). Barlow’s proposal for a National Institution was especially attractive to Peale during this time. The academy’s decision to commission a building in summer 1805 appears to have retrained Peale’s attention on a persistent concern: finding a permanent home for his own museum collection, which had been housed in three different locations since the 1780s.[65] When Barlow’s Prospectus, which recommended that an art museum be part of the National Institution, began circulating in 1806, Peale sensed a golden opportunity. “I have not seen the Pamphlet, and therefore don’t know whether my Museum might not be imbraced among the first of its establishments,” he wondered aloud to Jefferson in the first of several letters expressing his aspirations. “At my time of Life I cannot help feeling some Anxiety to know the fate of my labours. Every thing I do is with a view to a permanency, yet at my death there is a danger of its being divided or lost to my Country.”[66] Peale grew more optimistic as Barlow’s proposal circulated through government channels: “very probably,” he told John Isaac Hawkins, “my Museum will be attached to that great Seminary.”[67] Although he must have been disappointed when Congress failed to advance Barlow’s idea, he continued to advocate for his museum’s future even while immersed in planning the academy exhibition.[68]

Peale’s indirect appeal to Barlow continued as the viewer moved right along the exhibition walls, where ten of Smirke’s eleven paintings (“masterly,” according to Peale) appeared horizontally beneath West’s paintings of Lear and Ophelia. Smirke’s paintings formed the basis of the engraved illustrations in The Columbiad and, on the academy walls, they served to visualize and recommend Barlow’s publication to interested readers. (We have substituted engravings for The Columbiad paintings, which were painted ca. 1805–6 and remain unlocated, in our digital visualizations.) Rebora has described in detail the subjects portrayed in the images, which chronicled a triumphant history of the Western world, commencing with a scene picturing a narrator-spirit appearing to an imprisoned Columbus and concluding with episodes from the end of the American Revolution. In retrospect, the series reads as a colonialist allegory, dramatizing tropes of conquest and violence. For academy viewers in 1807, it may have struck a nationalist chord, for Jefferson introduced an embargo against Britain shortly after the exhibition opened. Those who had recently been to Peale’s Museum might have also noticed that Rembrandt Peale’s text An Historical Disquisition of the Mammoth (1803) was arranged in a manner similar to the Smirke paintings: disassembled and individually framed, the Disquisition wrapped around the room housing the enormous skeleton of a mastodon.[69] At the academy, Peale reiterated a version of this installation, encouraging a sequential mode of looking and reading on the part of visitors.

For reasons that remain unclear, Peale interrupted the line of Smirke paintings at the center with a biblical scene painted by the Dutch artist Adam Pynacker. Fulton identified the work as Angel Appearing to the Shepherds, “a charming work for effect and transparency.” Peale squeezed another canvas from Fulton’s collection to the right of the last Smirke painting. He was unsure of the artist’s identity, asking Fulton: “Wouvermans?” (The Pynacker, annotated number 12 in Peale’s sketch, is unidentified, although the title closely corresponds to a work by the artist at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Annunciation of the Shepherds, ca. 1640. The “Wouvermans,” a reference to the Dutch painter Philip Wouwerman, also spelled Wouwermans, is annotated number 16 in Peale’s sketch; it is not included in Fulton’s published account.)[70]

Together with The Columbiad paintings, Benjamin West’s dramatic paintings centered the exhibition spatially (figs. 14–15). In hanging them side by side, Peale also displayed his familiarity with the conventions of European academic exhibitions, which gave pride of place to large, significant works of art.[71] King Lear was popular in the eighteenth-century London theater and, according to Allen Staley and Helmut von Erffa, the heath scene was “the most frequently depicted of all Shakespearean subjects.”[72] Boydell’s catalogue of the works at the Shakespeare Gallery explained the scene in detail: Lear, estranged from his family and crown, wanders onto a moor with two loyal attendants, Kent and the Fool, in the thick of a storm whose force equals Lear’s inner turmoil. As they prepare to take shelter, they are confronted with a bedraggled figure (Mad Tom, the son of a nobleman in disguise). Lear is stunned back to his senses by Tom’s battered condition. He utters lines that reveal a newfound sense of humility: “Is man no more than this? Thou owest the worm no silk, the beast no hide, the sheep no wool, the cat no perfume.” In sympathy with Tom, Lear tears off his own clothing. This is the moment that West represents, as Lear cries, “Off off you lendings:—come, unbutton here.”[73] The scene offered potent material for a history painter like West, for it represented a transformation both dramatic and didactic: a king, selfishly despairing of his own fate, recovers his humanity through an encounter with less fortunate beings.

West likewise chose to represent a turning point in Hamlet for his painting Ophelia. In act 4, scene 5 of the play, Ophelia appears at court before the King (Claudius) and Queen (Gertrude) of Denmark. Her actions seem insensible to the assembled figures: doubly aggrieved by the death of her father Polonius and her tortured relationship with Hamlet, she speaks and sings incoherently, scattering flowers through the air. Her brother, Laertes, comes to her defense, supporting her with one arm while appealing heavenward with the other for an explanation of her insanity. Like Lear, and many other works in the genre of history painting, West’s picture was intended to communicate a moral. Exhibition visitors may have discerned a model sibling in Laertes, who stands protectively alongside Ophelia even as others glance away in dismay.

Encountering West’s paintings side by side at the academy, viewers would have seen a pair of thematically related pictures that also echoed one another formally, from the matching poses of Lear and Laertes in the foregrounds, to the framing device of architectural features at right, to the use of bright red throughout the compositions. They also encountered ambitious history paintings, grand in size and didactic purpose, of the sort familiar at British public exhibitions but rare in the early United States. Peale recognized their significance when he complimented Ophelia: “It fixes the attention of the beholders more than the other, yet both are in a grand Stile of composition and finely painted.”[74] The phrase “grand style” evoked the term Grand Manner, the academic mode that West and his British contemporaries popularized at London exhibitions. Peale may have intended to call attention to the importance of history painting within academic art practices by grouping West’s Shakespearean narratives together with Smirke’s paintings.

Fulton, however, was skeptical of this arrangement. “I fear that the effect of Mr. Smirks delicate paintings may be diminished if Suspended under the bold works of Mr. West,” he responded upon receiving Peale’s drawing. He gently offered an alternative: “it is therefore to be considered whether it is not best to hang them by themselves and about eye high with this inscription {Eleven pictures by R. Smirke Esqr. from Mr. Barlows Columbiad.”[75] He sent Peale a sketch to illustrate the idea (fig. 25). Fulton’s proposal surely had a secondary purpose, for his caption explicitly named Barlow’s poem as the raison d’être for Smirke’s paintings, thereby recommending The Columbiad for sale to potential buyers. Peale’s response, if any, was not recorded, and we do not know if he adjusted his hanging to please Fulton.

Arriving at the last segment of the exhibition, in the northwest part of the room, visitors found a wall of paintings varied in genre and subject. In this arrangement, the installation complemented the introductory wall, forming a bookend in concept and appearance. Peale recognized Academy President George Clymer (“No. 14”) by prominently displaying his portrait over a door (1807; fig. 26); aptly, the painting echoed the position of West’s self-portrait over the other small door in the room, thereby linking the actual and honorary leaders of the institution. The pairing also recalled the encomiums to West that Clymer had declared in his spring address to the academy. To the right, Peale placed Raphael West’s Oliver and Orlando, the third canvas Fulton had acquired from the Boydell Gallery sale. It provided a visual balance with the larger canvases on the walls to the left and a clever retort to the story of Abel, for in place of fratricide it pictured Orlando rescuing his brother Oliver from the claws of a lioness.[76] (The painting is unlocated and represented in our digital visualization by an engraving dated 1798; fig. 27.) Peale’s efforts to create several pairings between the first and last walls suggest that he had absorbed period tastes for balance and symmetry in exhibition design, in particular contemporary desires to see pendant pairings of works that shared similar sizes or related subject matter.[77]

Three smaller works beneath Orlando completed the exhibition: an unknown picture that Peale simply denoted with a blank square, a portrait of a man by Jan van Ravestyn (Jan Anthonisz van Ravesteyn, 1572–1657) (annotated “No. 13,” an unidentified Portrait of an Old Man, wittily denoted by Peale’s sketch of a profile), and the eleventh Smirke painting. Fittingly, as the endpoint of the exhibition, this picture represented The Final Resignation of Prejudices (engraved ca. 1805–6), looking forward to a peaceful future for the US (fig. 28).[78]

Peale was pleased with the appearance of the exhibition room. “I am delighted with your collection of Pictures,” he told Fulton, “several of them are wonderful works of art.”[79] He had good reason to be satisfied. The sheer diversity of works in Fulton’s collection tantalized Peale’s appetite for designing innovative displays. Peale was already experienced in attracting viewers to his museum through arrangements of portraits and natural specimens that visualized Enlightenment taxonomies; at the academy, he must have relished the rather different challenge of balancing paintings of varying sizes, subjects, and styles into a lively and coherent order. His arrangement yielded groups of paintings organized by school (European paintings), patrons (Barlow, Fulton, and West), and a very specific project (The Columbiad). The portraits of Rubens Peale and George Clymer that Peale added to the exhibition linked Fulton’s collection, formed on the distant shores of England, to the local ambitions of the academy and his own family. The multiple objectives of the exhibition’s stakeholders—Fulton, Peale, and the academy’s directors—thus sat side by side on the rotunda walls, neither holistically integrated nor competing with one another.

No matter how “wonderful” Peale deemed Fulton’s paintings, though, he surely found some of them difficult to hang. As we have deduced from our research and digital visualizations, West’s paintings were too wide for Dorsey’s walls. Documents from 1807 suggest how Peale worked to resolve this dilemma.

West on the Walls

Peale’s sketch discloses valuable information about the installation, yet it also conceals some of the problems he faced. The drawing flattens the circular walls of the rotunda, for example, implying that the paintings lay flush against the walls. However, as Peale acknowledged, the pictures inclined forward; in the case of the largest ones, such as Lear and Ophelia, there would have been considerable gaps between the wall and the stretchers.

Moreover, Peale’s diagram conveys at best a general sense of the relative scale of the paintings. As a matter of convenience, it represents the installation as a geometry of squares and rectangles fitted above, alongside, and between the two vertical spaces to the left and right marked “door.” Moreover, it does not communicate the size and appearance of the picture frames. Happily, at least one original frame from the exhibition has been preserved: the Boydell Gallery frame for Lear, which, according to Peale’s correspondence, accompanied the painting from London. Six inches wide, colored with gold leaf and decorated with carved and applied ogee moldings, it suggests how period frames would have filled the spaces between the canvases, enlivening the rotunda with gilded ornamentation (fig. 29).[80] We have reproduced the general appearance of this frame around Lear and Ophelia (which, as another Boydell Gallery picture, probably featured a very similar frame) in the three-dimensional reconstruction and used it as a guide to create gilt frames for the other paintings.

Most problematically, Peale’s sketch disguises key aspects of the rotunda’s architecture. The Port Folio’s description of the interior identified walls consisting of “eight tall pedestals alternating with an equal number of recesses which open to stair-ways or intended additional rooms.” If we assume a symmetrical layout of the gallery’s architecture, this account suggests that each half of the room—the east side and the west side—featured four “pedestals.” These pedestals were the tall plaster walls, measuring about twelve feet wide by eighteen feet high, that carried the weight of the dome. In Peale’s sketch, the square labeled “Abel” appears in the location of one of these pedestals; “Orlando” occupies a second pedestal. The image depicts the space that stretches between the two doors as a single stretch of wall. Per the Port Folio, however, two pedestals, not one, must have occupied this area. Intentionally or not, Peale misrepresented the wall occupied by Lear, Ophelia, the Smirkes, and the Pynacker as one continuous space.

To appreciate the practical implications of this inaccuracy for Peale’s installation, we also need to consider the “recesses.” An “equal number of recesses” appeared between the eight pedestals. Five of these recesses opened onto doorways. Peale noted the location of three of these doors in his sketch: the front door and two side doors. However, his drawing does not convey how the side doors were set back from the room, nor does it indicate how the overdoor paintings—West’s self-portrait and Peale’s portrait of Clymer—appeared within these recesses. Most importantly, it omits one recess altogether. As the Port Folio explained, several of the “recesses”—three, to be exact—were purely ornamental, anticipating the construction of “intended additional rooms.” As our digital reconstructions of the room make clear, these recesses would have appeared at the due west, north, and east points of the room (figs. 11–12). Therefore, the recess at the midpoint of the western wall would have occupied the space where Lear and Ophelia meet in the sketch. Instead of hanging on one continuous wall, as Peale’s drawing implies, the paintings would have been mounted on two separate pedestals, divided by a recessed feature.

Why did Peale exclude these architectural details from the drawing he sent to Fulton? Perhaps he thought them unnecessary in a sketch designed to offer a glimpse of the installation. Or maybe he wished to spare himself the embarrassment of explaining how awkwardly West’s paintings had to be installed. At twelve feet wide unframed, both Lear and Ophelia matched the very width of the pedestals. Framed, they exceeded it, for the width of the Boydell frames added six inches to either side of the canvases. At thirteen feet framed, then, each painting would have extended beyond the edges of the walls.

The problem was further complicated by Peale’s placement of the portraits of Fulton and Rubens Peale. Peale stacked these paintings one atop the other on the pedestal to the right of the southwestern-side door and to the immediate left of Lear. Framed, the larger of the two—Fulton’s likeness—consumed just over two feet of wall space. That left less than ten feet for Lear (and the four Smirke paintings that hung below it) on the same pedestal.

For Peale, the only logical solution to this mathematical dilemma was to push Lear to the right so that it extended across much, if not all, of the recess at the room’s western axis. James Kelleher has estimated the width of the recesses as six feet wide, using comparable data for the dimensions of rotunda spaces, including the Bank of Pennsylvania. By our calculations, Lear must have covered at least three feet of this recess. The painting of Ophelia might have met it nearly halfway; the rest of Ophelia would have projected across the third pedestal in the room. Together, then, the two paintings would have obscured the opening formed by the decorative recess. The 3-D digital reconstruction of the academy exhibition, correctly scaled to represent the width of the framed paintings, demonstrates the challenges of this situation. Like a Tinkertoy construction, the installation had to fit squares atop curves.

The final puzzle in this scenario is the painting by Pynacker. Peale’s sketch shows it hanging beneath Lear and Ophelia, bridging the gap between them. But how could the Pynacker occupy a vacant recess? An explanation may lie in a curious account of work performed in the exhibition room. In July 1807, as laborers continued to paint the walls, Peale invoiced the academy for “Tacks for fastening the Canvis of the Doors & Carpeting” and “Towlinnen to Cover sd. Doors.”[81] “Towlinnen,” which Peale inscribed as a single word, probably meant “tow-linen” or “tow-cloth,” a cheap, heavy textile used for clothing and the construction of tents.[82] Peale’s note suggests he fastened this canvas-like material over several doors. Did he mean the recessed openings in the east and west walls, which Dorsey had designed as the location of future doorways? Was he trying to create the illusion of continuous walls within the rotunda by hanging canvas in these spaces? Could a durable fabric like tow-linen support a small painting? This intriguing record suggests how Peale could have resolved the placement of the Pynacker—and created a wall-like backdrop behind Lear and Ophelia, obfuscating the opening between the pedestals. The effect might have resembled the use of scrims in museums today to block out windows or create barriers between rooms.

How Peale managed the tricky nature of the whole installation remains unclear. He left no explanation regarding the methods he used to hang the pictures on curved surfaces and across recessed openings. But he did record expenses for hardware and a blacksmith after installing the exhibition, suggesting that labor and materials exceeded the usual needs of installation.[83]

No wonder Peale longed for a “more useful” space, even before Fulton’s collection had arrived in Philadelphia. As an experienced museum proprietor, he could foresee the problems of hanging paintings on the sloping walls of a rotunda, a room that had been designed for exhibiting plaster casts.

Promotion and Reception of the Exhibition

Throughout their planning, Peale and Fulton had agreed on one objective: to persuade the academy to acquire a collection of West’s paintings. “You are now about to make a fair experiment of the public taste for fine paintings,” Fulton declared to Peale as the exhibition opened, “and from the mony which will be received we can judge of what might be received were the proprietors of the academy to purchase a good collection and the inducement to such purchase. To excite curiosity at the time of announcing and Exhibiting them it will be well to raise their fame by something handsome in the public prints, for to see and Judge by public opinion & for one who has a knowledge of the arts.”[84]

Three journals and newspapers, including Poulson’s, immediately published the squib that Fulton prepared to promote the exhibition. Though the report mentioned all of the works displayed, it echoed the installation’s emphasis on Lear and Ophelia, thereby serving Fulton’s interest of recommending West’s work to the academy. Lear’s “drawing and drapery . . . has never been surpassed by any artist,” readers learned. “The coloring is very fine; the Clair obscure well observed, the burst of lightning and glare of torch light, through the storm of rain and gloom of night produce an effect, a tout ensemble which cannot be described, and must be seen to be sensibly felt and understood.” Ophelia presented “one of the most elegant figures we have ever seen.” Together, the paintings reflected “great honor on the genius of our country, they are of themselves a basis for forming a good taste in our new school of art.”[85] The exuberant prose made an unambiguous case for West’s significance to the nation. If his paintings had previously served Boydell’s ambitions for an English school of art, Fulton remade them as foundations of a future art school.

Fulton’s efforts did excite curiosity, as Peale indicated when he sent a newspaper clipping to West:

It is scarcely necessary that I should tell you that these pictures are greatly admired. I have not been in much company since I placed the Paintings in the Building erected as an Academy of fine Arts (there being nothing of any account except the Casts which we received from Paris placed there before the collection as mentioned in this news paper), but some gentlemen who profess to be great admirer of the graffic art, say that the Picture of Lear exceeds any thing they had ever seen. they are not wanting in praise of Ophelia; of the figure of Laerties in particular.

“It is my intention,” Peale added, “to urge the directors of our Academy to make additional Rooms the ensuing Summer; one for an exhibition Room solely for Pictures & another to draw from the living figure, which I hope we may accomplish by this time twelve months. This institution,” he declared, “is growing into favor.”[86]

Conclusion

The 1807 academy exhibition evolved out of a series of transatlantic connections among artists, patrons, poets, and printers who collectively sought to champion the future of arts and letters in the US. The installation gave Philadelphians the opportunity to view a collection of paintings more varied in subject matter, genre, and style than had yet been visible publicly within the city. For Fulton, it was a venue to promote West to the academy and The Columbiad to readers; for Peale, it was a chance to advance the academy’s growth while cultivating new relationships for the benefit of his museum.

Their work did not end after the installation. Income derived partly from the display of Fulton’s collection allowed Peale to realize some of his intentions for the academy, though it would take a little longer than he had hoped (“we have been such wretched economists,” he admitted privately to his son Rembrandt).[87] He remained fixated on the prospect of an adequate exhibition room for paintings. In 1810, his wish was fulfilled: a gallery was added to the north side of the building.[88] The following year, the academy hosted the first annual exhibition of the newly formed Society of Artists. Peale promptly moved the three large West paintings and the Smirke canvases into the new space.[89]

Less successful was the effort to persuade the academy to buy a collection of historical paintings by West. Peale kept West apprised of their hopes. “I view with pleasure, as often as I have leisure, your charming Pictures which Mr. Fulton has been so obliging as to place in our infant Academy. It is giv[ing] your countrymen the opportunity of feeling the powers of your Pensil, very many of whom otherwise could not know you but by report. I was anxious to know in what degree the People of this City might be interrested with an Exhibition of large historical Works,” he wrote in 1808.[90] But the academy, as Rebora has persuasively argued, prioritized the expansion of its building over the growth of its collection. Fulton continued to lobby the academy until Clymer stressed the lack of resources. Notwithstanding the graceful façades of the academy and Latrobe’s buildings, Clymer suggested that Philadelphia was more of “an Amsterdam than an Athens.”[91]

Privately, Peale may have been satisfied with the success of the 1807 exhibition, for he obtained the kind of gallery he had long desired and needed for hanging paintings. He also succeeded in strengthening his ties to Barlow. Long after hanging Smirke’s paintings at the academy, Peale remained involved with The Columbiad. He arranged for the transportation of the engraved plates and helped encourage sales of the poem.[92] He gratefully displayed a copy donated to the Philadelphia Museum by Barlow’s wife, Ruth (“it is called for so often that I am afraid it will too soon get soiled, for we cannot refuse it to any Visitor who has paid for the sight of all that belongs to the Institution”), and he asked to copy a portrait of Columbus in Barlow’s possession.[93] The exhibition had given Peale entrée into Barlow’s circle, if not his National Institution.

Peale stayed in close contact with Fulton, too, through their mutual interest in West and The Columbiad. It is not clear if Fulton ever traveled to the academy to see his pictures. Yet Peale continued to urge him to visit, for he was already planning new projects: “I have many things to shew you, and much to say on future prospects.”[94] Although the 1807 exhibition would be their only collaboration, Peale and Fulton had established the potential of the academy to grow public interest in the arts.

Notes

[1] Charles Willson Peale to Robert Fulton, November 15, 1807, in The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, ed. Lillian B. Miller, Sidney Hart, Toby A. Appel, and David C. Ward, vol. 2 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988), 1047 (hereafter SP). All citations from this publication are vol. 2, part 2 unless otherwise indicated. We have preserved the original spelling and grammar as it appeared in Peale’s correspondence and other primary sources quoted in this essay, even when it makes for awkward reading. We have also preserved the appearance of “[sic]” and the addition of clarifying terms in brackets when such editorial annotations appear in transcriptions of primary sources in SP and other publications. Where it seemed helpful to clarify the meaning of a misspelled word in a primary source or transcription, we have added the correct spelling in the notes.

[2] Robert Fulton anticipated that the exhibition would inspire “our new school of art” in a widely reproduced essay he wrote to promote the event: “The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts,” Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia), November 26, 1807. See also “The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts,” The Democratic Press (Philadelphia), November 28, 1807; [“The Pennsylvania Academy . . .”], The Literary Magazine, and American Register 8, no. 50 (November 1807): 263–64. Port Folio reprinted the text several months later: “The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts,” Port Folio (Philadelphia), February 6, 1808, 87–88.

[3] Carrie Rebora explored Fulton’s collection and the academy exhibition in a groundbreaking article: “Robert Fulton’s Art Collection,” American Art Journal 22, no. 3 (Autumn 1990): 40–63. Our research is indebted to Rebora’s comprehensive study of Fulton’s collection. See also Joel Barlow, The Columbiad (Philadelphia, 1807); Yvette Piggush, “Visualizing Early American Art Audiences: The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and Washington Allston’s Dead Man Restored,” Early American Studies 9, no. 3 (Fall 2011): 716–47.

[4] Fulton to Peale, November 18, 1807, SP, 1049.

[5] The earliest effort to gather the work of numerous artists in a single exhibition also occurred in Philadelphia: the Columbianum exhibition of 1795, organized largely by Peale and held in the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall). On this event, see Wendy Bellion, Citizen Spectator: Art, Illusion, and Visual Perception in Early National America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 63–111. The academy began holding annual exhibitions of paintings in 1811; art organizations in other cities, including New York and Boston, followed suit in subsequent years.

[6] Research for this article transpired largely during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many archives and libraries were closed to visitors. Our findings thus draw extensively on the primary sources annotated and published in the Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale as well as the copious records preserved on microfiche in The Collected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, ed. Lillian B. Miller (Millwood, NY: KTO Microform, 1980).

[7] Peale to Fulton, November 15, 1807. “Poussan” is a misspelling of “Poussin.”

[8] On these points, see Catherine Roach, “Rehanging Reynolds at the British Institution: Methods for Reconstructing Ephemeral Displays,” British Art Studies no. 4 (November 2016), https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-04/croach; Paul Jaskot, “Thinking about Visibility and Invisibility in the Art Historical Canon: The Tensions between Evidence and Data in Digital Art History,” online lecture for the Toward a More Inclusive Digital Art History Project, February 27, 2021, sponsored by Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art. For more information see: https://editions.lib.umn.edu/.

[9] On the Philadelphia Museum, see David Brigham, Public Culture in the Early Republic: Peale’s Museum and Its Audience (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995).

[10] Peale to Angelica Peale Robinson, June 9, 1805, in Collected Papers (hereafter CP), series II-A, card 34.

[11] Benjamin Henry Latrobe to Peale, July 17, 1805, SP, 866. On the academy’s establishment and founders, see SP, 846; Frank H. Goodyear Jr., “A History of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1805–1976,” in In This Academy: The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1805–1976. A Special Bicentennial Exhibition (Philadelphia: The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1976), 12–48.

[12] “We have began again an attempt to form an Institution for the encouragement of the fine arts,” Peale reported to Raphaelle Peale, June 6, 1805, SP, 844.

[13] On West, see Helmut von Erffa and Allen Staley, The Paintings of Benjamin West (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1986); Susan Rather, The American School: Artists and Status in the Late Colonial and Early National Era (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016).

[14] Peale to Thomas Jefferson, June 13, 1805, SP, 852.

[15] Goodyear, “A History,” 17.

[16] Nicholas Biddle to Joseph Hopkinson, William Meredith, and Charles W. Peale, November 20, 1805, CP, series II-A, card 36. For a contemporary summary of the number of casts and busts, see “The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts,” Port Folio, June 1, 1809, n.p. The classical sculptures were brought to the Louvre following Napoleon Bonaparte’s conquest of Rome; in Paris, they formed part of the Musée Napoleon.