The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

with Allan McLeod

Introduction | Scholarly Essay | Interactive Features | Project Narrative

It is a combination of small means, to encourage art by some degree of the patronage once bestowed by popes and princes. It is by the people, and for the people.

—Lydia Maria Child

The term “unintended consequences,” popularized by sociologist Robert K. Merton in his 1936 article “The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action,” identifies outcomes that are not foreseen and intended by a purposeful action and posits that intervening into complex systems can create unexpected and even unwanted results.[1] The art world is one such complex system, comprising artists, critics, collectors, dealers, the public, and nonprofit exhibiting venues. A shifting and layered interplay of motives and incentives drives members of the system toward, hopefully, the creation, interpretation, exhibition, sale, and public display of the most meritorious works of art. However, such a definition of unintended consequences raises nearly as many questions as it answers—who is motivated and by what, what kinds of incentives are created, who responds to them, and, most crucially, who defines merit?

These and other questions were relatively new to the US during the antebellum period, when the structures and institutions necessary to fostering great artworks were beginning to develop. The American Art-Union (1838–52; fig. 1) represented a remarkably ambitious attempt to furnish many of the elements of a nascent art world, such as large-scale patronage, an exhibiting venue, criticism, and even rudimentary education for artists and the public, in order to encourage US art and artists. It began in New York in 1838 as the Apollo Gallery, and by 1839 it was established as a membership organization. At its height in 1849, it boasted nearly 19,000 members from almost every state in the country. For an annual fee of five dollars (about $130 today), members received an engraving after a painting by a notable US artist and the annual publication Transactions (1839–49) and later the monthly Bulletin (1848–53), which included commentary on contemporary US artists and news of the art world. Most importantly, members’ names were entered in a drawing for hundreds of original paintings and sculptures by living US artists (figs. 2, 3). The annual distribution of prizes was a major social event in New York, attracting crowds of thousands (fig. 4). Artworks to be distributed were displayed at the Art-Union’s immensely popular Free Gallery. More than 4,400 objects were exhibited and distributed over fifteen years, and according to the organization’s records over 230,000 people visited the gallery each year.[2]

Contrary to writer and abolitionist Lydia Maria Child’s idealistic assessment that the American Art-Union was “by the people and for the people,” it actually became an exceptionally powerful and influential patron in its own right. The American Art-Union led the way in patronage in New York and throughout the country during the 1840s, a decade that began with euphoric optimism and ended with the heightened tensions that would come to a climax in the Civil War. Historian Daniel Walker Howe recounts that in barely two generations since its founding, the country’s population doubled every twenty years, and its robust economy was driven by new technologies such as the telegraph and the railroad. United States citizens “dreamed without embarrassment of extravagant utopias both spiritual and secular.”[3] During the period that the Art-Union was active, the nation’s boundaries expanded to the Pacific through the annexation of Texas (1845), the addition of the Oregon country (1846), and the acquisition of the Southwest in the Mexican Cession (1848). This stunning territorial expansion was accompanied by contentious conflicts about the spread of slavery into the new territories.[4] In 1848, a year of revolution in Europe, writers praised the peaceful mixing of classes at the Art-Union’s Free Gallery (fig. 5). According to The Knickerbocker:

Its hall shows the progress of the hours. . . . First come the noisy boys and girls, on their way to school; then the staid merchants drop in as they go down to their counting-houses; then the strangers from the country . . . about noon the gentlemen in moustaches and yellow [gloves] lounge about the seats, yawning in the faces of the fashionable ladies . . . in the afternoon comes the returning throng from the offices and counting houses, while in the evening the working-men . . . don their uneasy Sunday-coats and come hither by hundreds, escorting their wives and children, and all their female relations.”[5]

Unfortunately, the experiment was short lived. Opposition grew, critics of the organization alleged that its distributions constituted an illegal lottery, and subsequent events led to an 1852 court case that proved to be the Art-Union’s downfall.

The foundational study of the American Art-Union is Mary Bartlett Cowdrey’s American Academy of the Fine Arts and American Art-Union of 1953, which includes an institutional history and summary statistics by Charles E. Baker, along with an index of artworks it lent and distributed.[6] Maybelle Mann brought further attention to the organization with exhibitions of its engravings in 1977 and 1987.[7] A few recent studies have examined the subjects of the artworks engraved and distributed: Wendy Greenhouse’s 1989 dissertation examines themes from Tudor and Stuart history and notes that of the over one hundred depictions of such subjects created during the Art-Union’s existence, almost half were exhibited there, and five of them were chosen either as engravings or Bulletin illustrations.[8] In 1991, Carol Troyen shifted the focus to landscape, observing that the organization avoided landscape subjects in its engravings and seemed ambivalent about the genre throughout the 1840s.[9] Christopher Oliver’s recent master’s thesis approached engravings as an ongoing discourse on the development of a national school of art that reflected the natural tension between looking to Europe for models and building a distinctive US identity.[10] Other scholars have attempted to discern the character and intentions of the organization’s management through their occupations and political affiliations. In 1995, Rachel Klein examined the American Art-Union’s committee of managers and their relationship to artists.[11] Joy Sperling’s 2002 analysis compared the radical stance of those leading the Art Union of London to those at the American Art-Union.[12] Patricia Hills examined the institution’s choices of engravings as evidence that its managers promoted national subjects that would justify their personal empire-building agendas and business interests.[13] Most recently, the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, mounted an exhibition of Art-Union prints and selected paintings with an accompanying catalogue that reintroduced the organization to a general and scholarly audience.[14]

These important studies concentrated on the Art-Union’s external face through its public statements and its widely distributed engravings. However, its actions frequently contradicted its stated aims, creating unexpected results in the antebellum art market. This essay will compare the institution’s outward face, via its external statements, to its inward face, seen in its internal documents and actual practices. The comparison will show that even though the Art-Union publicly promoted history painting, it was in fact a much stronger advocate of landscape painting. First, an examination of its external statements and practices will illustrate its consistent public support of traditional history painting—the subject matter most esteemed by European artists and collectors—through its publications, in the works chosen for engraving, and in its most proudly publicized purchases. Next, the Art-Union’s external face will be contrasted with its internal practices and its quiet but pervasive support of landscape painting through its correspondence with artists, the instructions and advice disseminated in its publications, and most importantly, its purchases. While the American Art-Union is well known for supporting the early efforts of the Hudson River school’s great names, the handful of choice works by these artists was underpinned by still larger numbers of landscapes by lesser-known artists that were distributed throughout the country, establishing a truly national taste for American landscape, perhaps contrary to the Art-Union’s more high-minded intentions.

The true nature of the Art-Union’s impact has gone unnoticed in the past, probably because it was obscured by the sheer quantity of artworks involved and the volume of its internal records, which encompass 109 volumes.[15] The advent of digital tools, both basic ones such as spreadsheets and databases, and newer, more sophisticated ones such as GIS mapping and interactive charts, offers ways to analyze this large body of data and reveal a more nuanced and sometimes surprising view of the Art-Union’s activities and impact. This project began with the compilation of data alongside a close examination of internal documents and correspondence. Preliminary analysis was conducted using database queries, which suggested that interactive maps and timelines would best demonstrate the organization’s reach, both in terms of membership and in artworks distributed throughout the country. In addition, the data lent itself to an interactive chart that shows the predominance of landscapes over any other genre of painting in the artworks that made their way across the United States and beyond.

The American Art-Union had a decisive impact because it was the first institution that could influence US taste on a national scale. The Art-Union Membership map shows its broad extent and startling growth, with bubbles sized in proportion to the number of members for each state. Clicking on each state offers a breakdown of membership by city. Moving the slider below the map through the years of the Art-Union’s existence vividly demonstrates how the institution grew significantly not only in numbers, but also in geographic scope, from about 800 people almost entirely based in New York City in 1839 to nearly 19,000 people in nearly every state by 1849.

The External Face: Elevating “a Higher Range of Subjects”

The Art-Union’s strong and sustained promotion of history painting was based on the long-accepted hierarchy of genres elucidated in the Discourses of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–92), English portraitist and president of London’s Royal Academy. Reynolds placed history paintings at the top of the hierarchy of subjects, followed by portraits, genre scenes, then landscapes.[16] Accordingly, the Art-Union managers declared history painting its highest aim throughout the life of the organization. In 1841, Transactions encouraged subjects from US history and ideal themes with “their glowing conceptions of beauty, grace, and grandeur.”[17] The 1847 issue of Transactions predicted that the Free Gallery would become a great source of instruction that would allow artists to “treat a higher range of subjects than those which the majority of them have hitherto attempted,” and that though landscapes were admired, they would like to see more historical subjects.[18] Two years later, the Art-Union congratulated itself on its progress in inspiring artists to work on “a higher range of subjects.”[19]

The most studied aspect of the Art-Union, and the one that caused the managers the greatest difficulty, was choosing subjects for engravings. While examining the successfully executed engravings has provided useful insights, supplementing them with its unrealized projects, as documented in letters and meeting minutes, provides a fuller picture of the Art-Union’s aspirations (n.b.: engravings were distributed the year after membership was purchased; for instance, engravings for the members of 1845 are dated 1846). Its challenges began in its earliest days. The first subject chosen was General Marion in His Swamp Encampment Inviting a British Officer to Dinner, painted by John Blake White and engraved by John Sartain for the subscribers of 1840 (fig. 6). This unassailably patriotic subject was based on a legend from the American Revolution: after negotiating with a British officer for a prisoner exchange, General Marion invited his adversary to dinner and produced just a few potatoes roasted in the fire and served on a stump. The Englishman was so impressed with the self-denial that the Revolutionary cause inspired that he resigned his commission.[20] For 1841, the Art-Union managers lamented that they had wanted to select a subject from national history, as they had done the previous year, but they found no suitable recent work, so they chose The Artist’s Dream, painted by George H. Comegys and engraved by Sartain (fig. 7). Though not a US subject, the image of the exhausted artist attended by the spirits of the old masters—Raphael, Titian, Da Vinci, Rembrandt, Rubens, and Reynolds—constituted an allegorical subject.

That same year, the Art-Union announced an award of $500 for the best original picture to be used for the 1843 engraving. When none of the paintings submitted met their expectations for a historical painting of a national subject, the prize money was used to purchase more paintings.[21] For the 1842 engraving, the managers chose a classical subject, John Vanderlyn’s Caius Marius on the Ruins of Carthage, taken from Plutarch’s Lives. The painting won a gold medal at the 1807 Paris Salon and toured the United States in 1816. It was then engraved, after some delays, by Stephen Alonzo Schoff (fig. 8).[22] Cultured citizens of the period delved deeply into the classics, and though it did not depict a national subject, the engraving showed the promise of US artists.

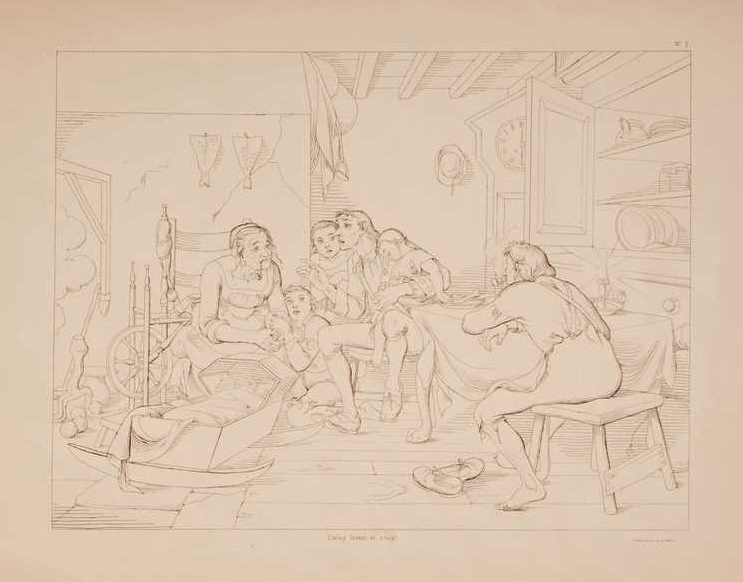

The engraving for 1843 was the Art-Union’s first genre subject, William Sidney Mount’s Farmers Nooning of 1836, engraved by Alfred Jones (fig. 9). The managers must have identified him as a representative US genre artist who incorporated high art conventions into scenes from everyday life; here, Mount depicted a group of farmhands at their lunch, with a classically posed black man being teased by a mischievous boy while taking a nap in the sun. The organization’s foray into genre subjects continued in 1844 with Francis Edmonds’s sentimental courtship scene Sparking (fig. 10), which depicts a young couple in intimate conversation by a glowing fireplace, their propriety assured by the woman washing up in the adjoining room. However, the institution felt compelled to represent history painting in some way and augmented their offering with Escape of Captain Wharton after a drawing by Thomas F. Hoppin (fig. 11). It illustrates an episode from James Fenimore Cooper’s 1821 novel The Spy,[23] which traces the fortunes of a family divided by their loyalties during the Revolutionary War.

Into the mid-1840s, the American Art-Union worked to create a dialogue between historic and genre subjects. In late 1844, the organization pursued the possibility of engraving Emanuel Leutze’s Oliver Cromwell and His Daughter (fig. 12),[24] though it did not come to fruition. That year they made another attempt to solicit historical subjects for engravings, contacting several artists, including John Gadsby Chapman, Durand, Charles Ingham, Henry Inman, Hoppin, John S. Morton, Mount, William Page, Samuel B. Waugh, and others, for a picture to engrave for 1845 members. Each was asked to submit a sketch of a subject of a national character comprising five to seven figures, and each would be paid $70.[25] While there is no indication of their responses, Durand probably proposed The Capture of Major Andre (fig. 13), which became the subject for 1845. Drawn from an incident of the Revolutionary War and painted by an artist who had just become president of the National Academy of Design (though by this time he was better known for landscape subjects), it met the Art-Union’s stated goals perfectly. The selection for 1846 was engraved by Charles Burt after Leutze’s Sir Walter Raleigh, Parting with His Wife (fig. 14), depicting the English explorer, spy, and politician bidding farewell to his wife on his way to his execution. The Literary World (edited by Evert Duyckinck, a member of the Art-Union’s management committee) called the subject “by far the most elevated” that the institution had undertaken to date.[26] At the same time that this painting was being engraved, the organization arranged for Schoff to engrave yet another, much larger, historical subject by the same artist for 1847, Leutze’s Return of Columbus in Chains to Cadiz (William R. Talbot, Jr. collection as of 1975), which had been distributed to Richard J. Arnold of Providence, Rhode Island, in 1843. After three years of negotiations, great delays in completing the engraving, and the owner’s refusal to extend the loan, the institution was forced to cancel the project.[27]

At the 1847 annual meeting, it was announced that because of the failure to engrave Leutze’s Columbus subject, members would receive two prints after George Caleb Bingham’s The Jolly Flat Boat Men, engraved by Thomas Doney, and Daniel Huntington’s A Sibyl, engraved by John W. Casilear (figs. 15, 16).[28] The pair has been understood as a successful combination of genre and historical subjects, and of the Art-Union’s competing mandates to provide subjects that would both educate and appeal to its members.[29] Bingham’s classical pyramid composition is enlivened by the man’s spirited dance and the knowing look of the sailor at right. This large-format, raucous scene from life in the United States forms a striking contrast with Huntington’s lone robed female figure with eyes cast up to the heavens. The pairing of high-minded and popular subjects continued through the remainder of the Art-Union’s life, no doubt spurred on by continued pleas from such periodicals as The Literary World, which entreated the Art-Union in 1847 for a “higher order” of subjects for their engravings, hoping for more classical or poetic subjects rather than everyday subjects “that convey no graceful and refined images to the mind.”[30]

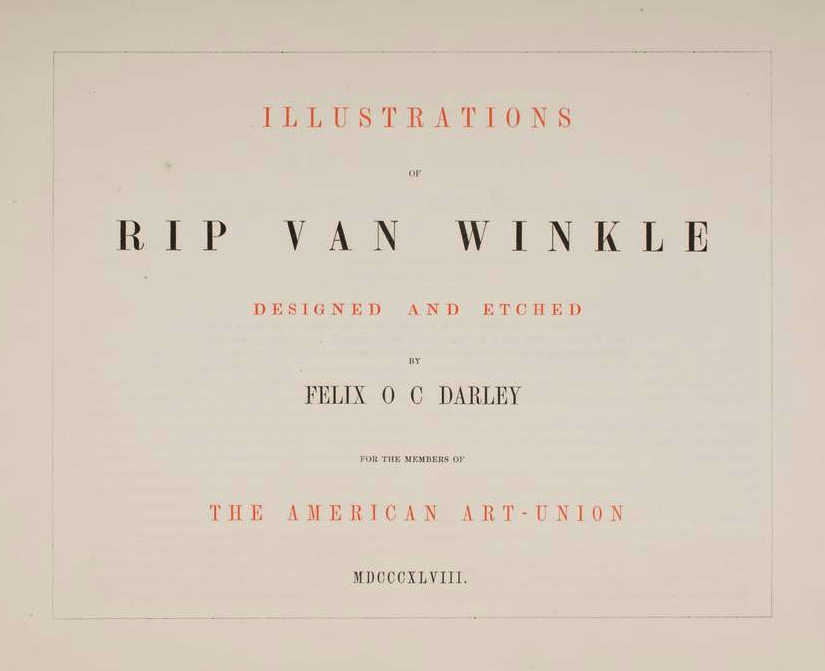

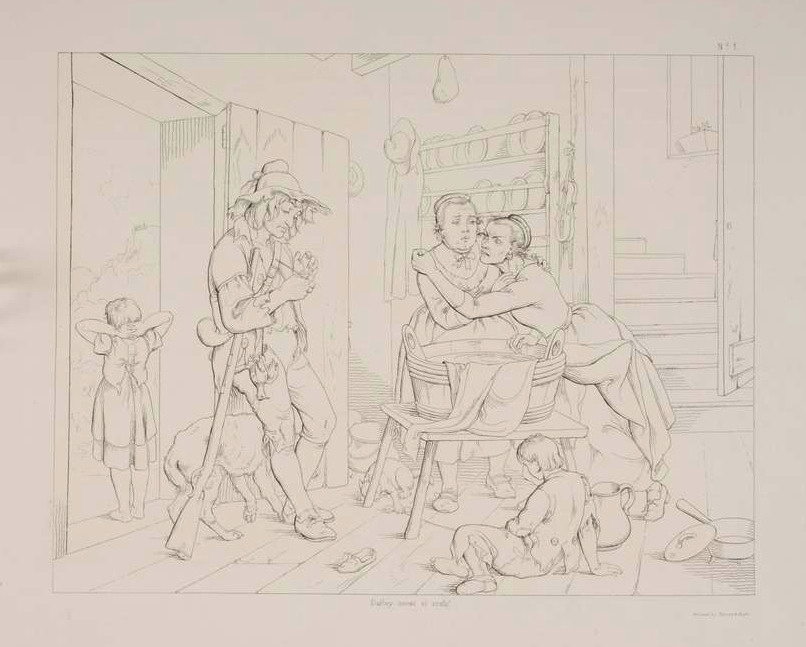

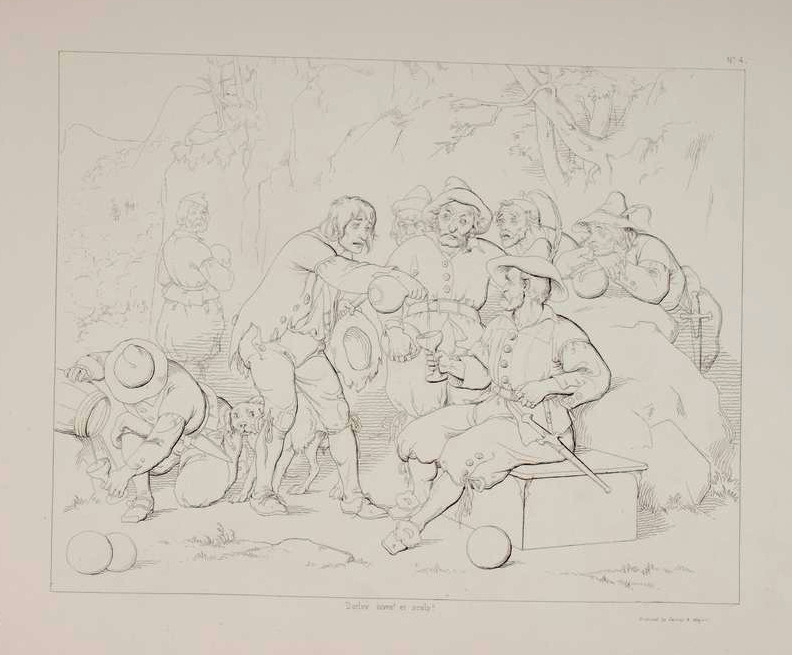

The engravings for 1848 once again paired a historic subject with a popular one. Charles Burt’s large folio engraving after Daniel Huntington’s The Signing of the Death Warrant of Lady Jane Grey (fig. 17) represented a subject from Tudor history: the designated heir to the throne, a Catholic, lost favor and was executed at the order of Protestant Queen Mary in 1554. It was accompanied by a lighthearted offering of line drawings illustrating Washington Irving’s beloved tale of Rip Van Winkle by F. O. C. Darley (figs. 18–24). The Art-Union proudly announced a forthcoming commission to illustrate another “popular American story” and anticipated future commissions to illustrate similar US literary works or poems.[31] Its high ambitions to promote US literature may have offered an attractive middle ground between the didactic and the popular.

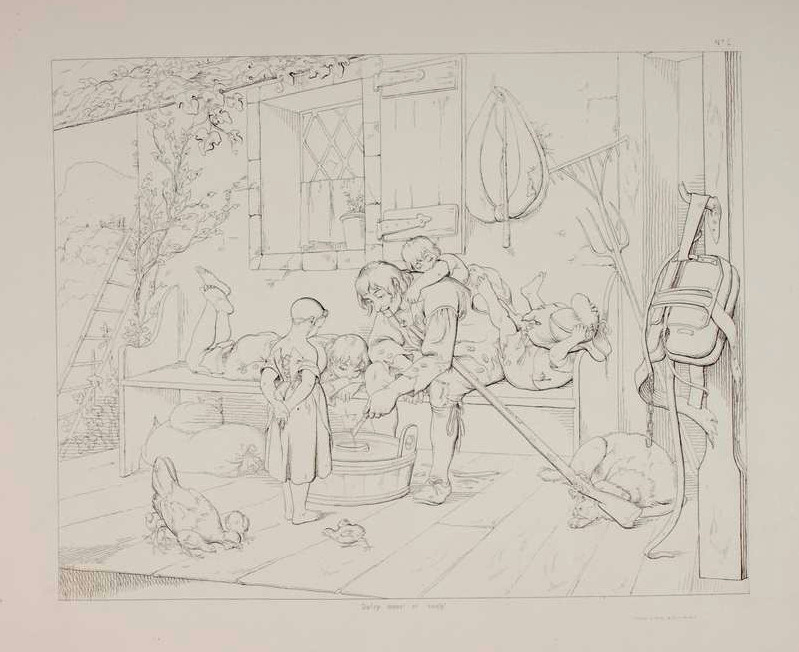

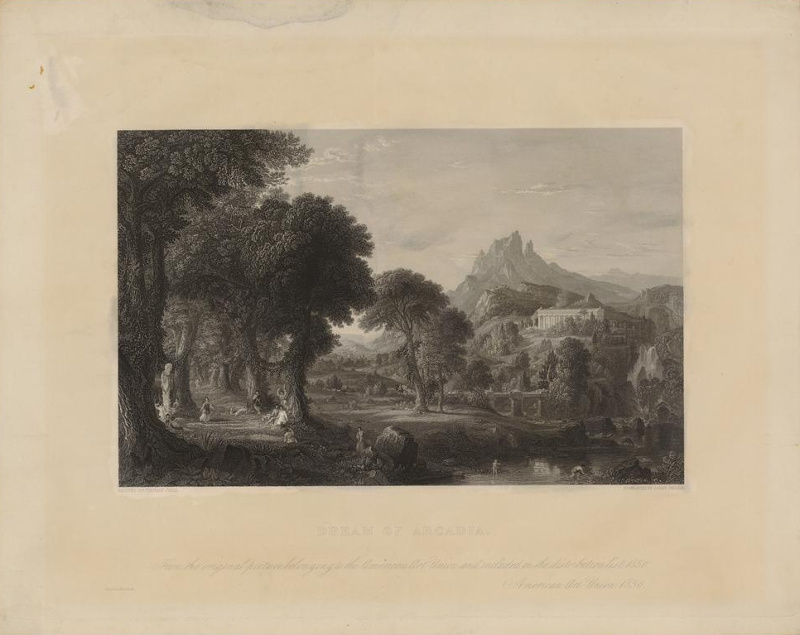

The engraving committee reported choosing a landscape subject for the first time for 1849, but only because they could not locate a suitable painting of a “higher Department of art” that was available. They temporized that it would bring variety to the engravings,[32] but their reluctance to engage in a landscape subject is clear. They were interested in a painting by Thomas Cole to commemorate his sudden and tragic demise earlier that year and commissioned James Smillie to engrave Youth (fig. 25) from Cole’s four-painting series, Voyage of Life, which had been purchased for the distribution of 1848. Although Youth did not depict a US subject, it combined landscape with an idealized, moralizing subject to form a hybrid between the history and landscape genres. It was accompanied by another series of line drawings by Darley illustrating another popular Irving story, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (figs. 26–32).

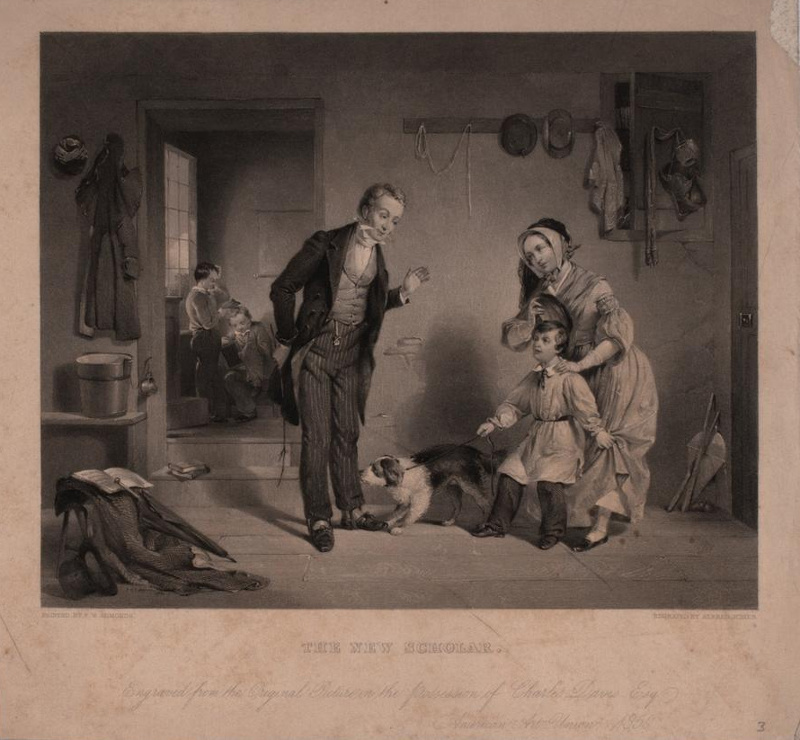

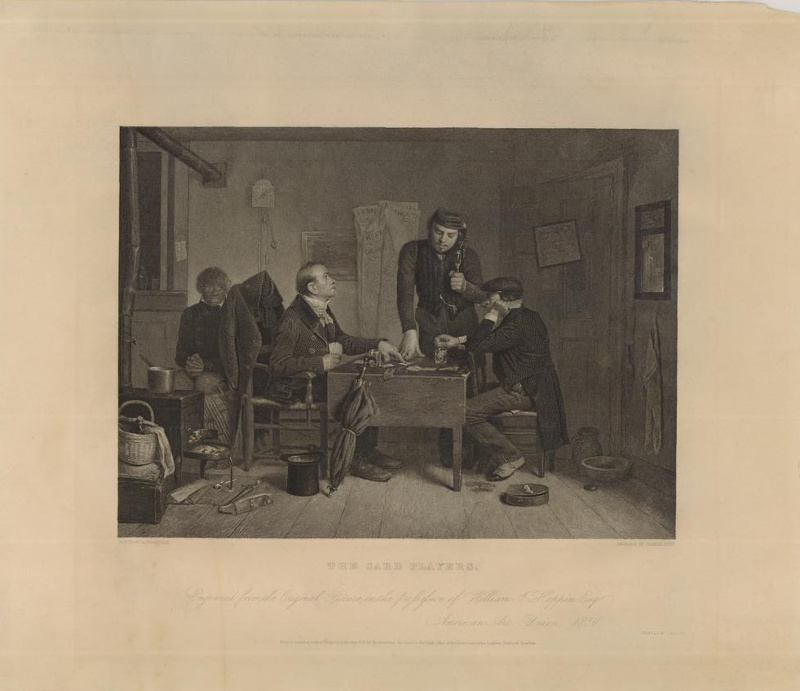

The year 1850 marked the climax of the Art-Union’s aspirations, as they introduced an innovation: the usual large folio print would be accompanied by a series of five smaller prints that would form what they called a Gallery of American Art. The large print was engraved by Charles Burt after Charles Leslie’s painting Anne Page, Slender and Shallow (fig. 33). The choice of a scene from Shakespeare suggests their keen and continued interest in historical subjects, even to the point of choosing a painting that was nearly twenty-five years old. It depicts a scene from act 3, scene 4 from The Merry Wives of Windsor, when Shallow advises his nephew Slender about how to woo Anne Page. The five small prints that would inaugurate the Art-Union’s ambitious new project measure about 7 1/2 by 10 inches and were intended to accumulate over time into a bound volume. The Art-Union announced that the small prints would eventually be “a great work, which will become in fact, the only and the most important engraved Gallery of American Art.”[33] They include Cole’s Dream of Arcadia, Durand’s Dover Plains, Edmonds’s The New Scholar, Leutze’s The Image Breaker, and Richard Caton Woodville’s The Card Players (figs. 34–38). The range of subjects spans two landscapes, two genre scenes, and one historical subject. For the first time, the Art-Union offered engravings of pure landscape subjects in order to create a comprehensive canon of US art that encompassed all genres that they considered important.[34]

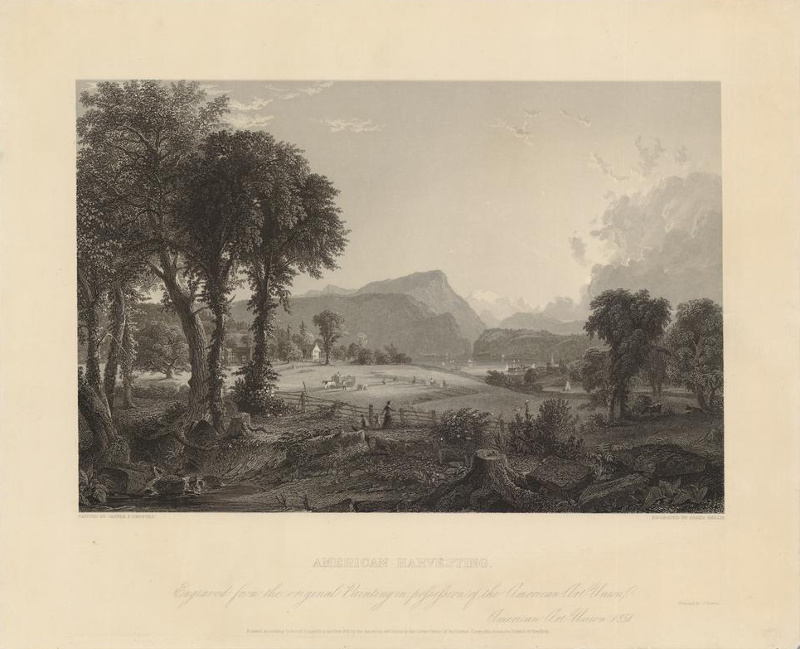

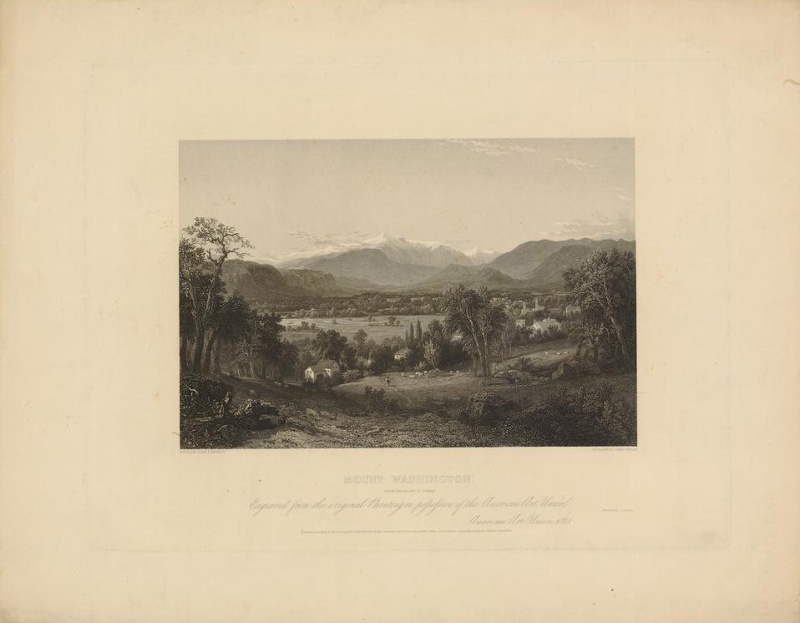

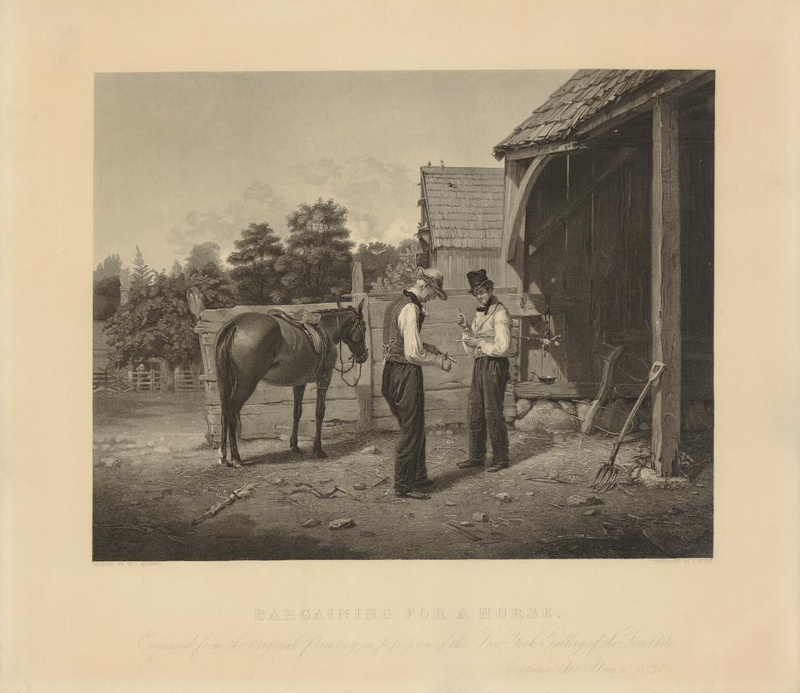

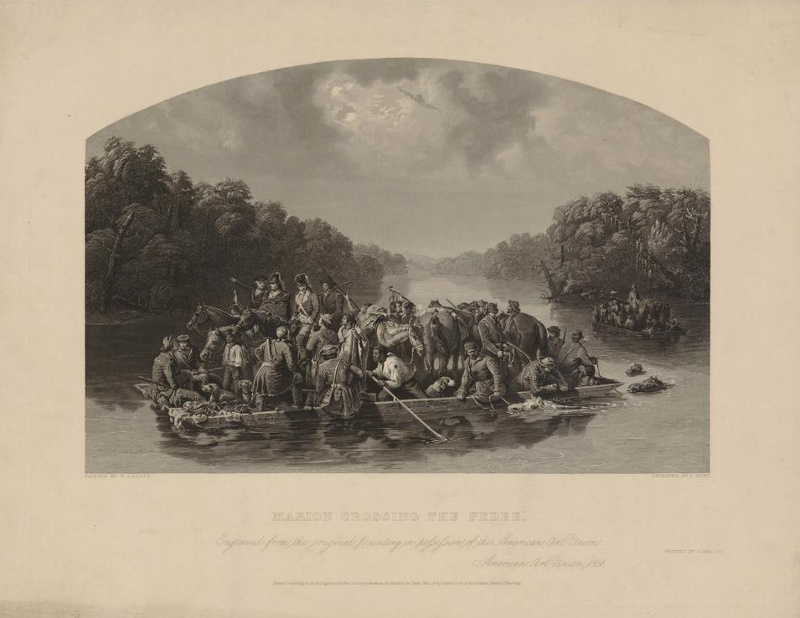

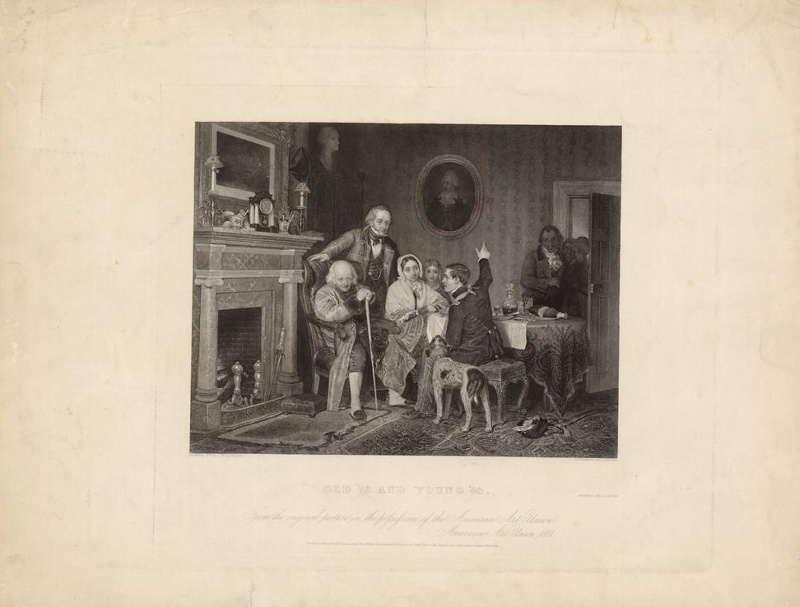

In 1851, the Art-Union distributed its last commissioned engravings, continuing their formula of one large print and five smaller prints toward their Gallery of American Art.[35] At one point, they considered engraving William Tylee Ranney’s Daniel Boone’s First View of Kentucky (fig. 39), but they chose instead Woodville’s Mexican News, engraved by Charles Burt (fig. 40),[36] a complex multi-figure composition that mediates between genre and history. It depicts a range of classes assembled on the front porch of the American Hotel, reading an opened newspaper over the shoulder of one of the figures; their reactions to what they read are echoed in the varied public responses to the war itself. The reason given for rejecting Ranney’s painting was merely that it was “inexpedient,” but the committee’s decision may have been affected by heightened sectional tensions leading up to the Compromise of 1850, which admitted California into the Union as a slave state, while the Utah and New Mexico territories would decide their status by a vote.[37] The legislation resulting from the compromise also introduced the Fugitive Slave Act, which aroused passionate opposition in the North. Its main architect was Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky, a slave state, and perhaps Ranney’s painting of its beginnings was considered a sensitive subject. On the other hand, the Mexican War (1846–48), though politically divisive, was over, and the resulting addition of significant territories made it seem to some like a great victory.[38] The five small engravings included Jasper Francis Cropsey’s American Harvesting, John Frederick Kensett’s Mount Washington from the Valley of Conway, Mount’s Bargaining for a Horse, Ranney’s Revolutionary War subject, Marion Crossing the Pedee, and Woodville’s Old ’76 and Young ’48 (figs. 41–45). The distribution of genres remained the same, with two landscapes, two genre scenes, and one historical event, but this time all were US subjects.

The American Art-Union would not publish any more original engravings before its demise in 1852. However, since engravings had to be arranged years in advance, the managers were already considering future subjects, and their plans show a continued interest in historical themes. It is very likely that they would have engraved the rest of Cole’s Voyage of Life series, after the success of the engraving Youth in 1849. They also made plans to engrave yet another of Leutze’s paintings, The Knight of Sayne (fig. 46), a scene from a German ballad in which Ermengarde, daughter of a squire, is promised to Kuno of Sayn if he can ride his horse up the rocky cliff to her father’s castle. With the help of gnomes, he makes the journey and wins his lady.[39] They also considered engraving a painting by Gilbert Stuart Newton called The Dull Lecture for 1852.[40] As the large folio engraving for that year, Newton’s picture was thought to form a companion piece to the engraving after Anne Page, Slender and Shallow. It was a similar interior view in an earlier century showing a young woman nodding off as she listens to an older man’s teachings. Like Anne Page, it was a historical subject with a hint of humor. However, it had already been engraved by Durand decades before (fig. 47). The chronology of the engravings and their subjects shows the Art-Union’s determined efforts to keep history painting at the fore, seasoned with amusing genre pieces and founded on a preponderance of national themes. Landscapes seem to have been a begrudging addition, with Cole’s Youth considered as a combination of landscape and allegory, and the smaller selections in the Gallery of American Art as almost obligatory inclusions to round out the fuller picture of the US art world.

Each year, Art-Union purchases of large and expensive history paintings by prominent artists were touted as incentives to join. Unfortunately, many cannot be found today, which may be a testament to the decline of interest in history painting and historic US art in general in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They included Durand’s copy after Vanderlyn’s Caius Marius in 1842 (location unknown), also distributed as an engraving; Leutze’s Return of Columbus in Chains to Cadiz, which had been considered for an engraving, and his Countess of Salisbury and Edward IV (location unknown) in 1843; Peter Rothermel’s De Soto Discovering the Mississippi (St. Bonaventure University Art Collection, Allegany) in 1844; Durand’s Arrest of Major Andre (Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham) in 1845, also distributed as an engraving; Daniel Huntington’s Bishop Ridley Denouncing the Princess Mary (location unknown) and William Tylee Ranney’s Washington’s Mission to the Indians in 1753 (location unknown) in 1847; Leutze once more with his Mission of the Jews to Ferdinand and Isabella (location unknown) in 1848; two distinguished works by Henry Peters Gray in 1849, the allegorical Wages of War (fig. 48) and the mythological Apple of Discord (location unknown), both warmly praised in the Bulletin;[41] and in 1850 Ranney’s Daniel Boone’s First View of Kentucky, even though it was not considered an appropriate subject for an engraving. In 1849, the institution announced plans for expanded activities, including more life-size history paintings.[42]

The Art-Union also advocated history painting through the aggressive promotion of US history painters and their work in its publications, Transactions and the Bulletin. From 1849 through 1851, the Art-Union distributed over 130,000 Bulletins annually throughout the country, making it a powerful tool for disseminating its views.[43] Ranney’s work on Marion Crossing the Pedee (Amon Carter Museum of Art, Fort Worth) was highly praised.[44] The April 1849 Bulletin noted that Huntington had just finished The Three Marys at the Sepulchre (location unknown) and had begun The Deliverance of St. Peter (location unknown).[45] It also reported that Leutze was in Düsseldorf working on The Attainder of Stratford (private collection), a subject from English history, and The Storming of the Mexican Teocalli by Cortez (fig. 49), a monumental production with over sixty figures that the Bulletin anticipated to be his best work yet.[46]

Leutze was a great favorite of the Art-Union. In addition to purchasing his works, the Bulletin praised his dedication to history painting, holding him up as the embodiment of its aims and ideals.[47] Through 1849 and 1850, the institution offered the latest news on his monumental Washington Crossing the Delaware (fig. 50).[48] Its arrival in New York in the fall of 1851 (though at the gallery of the Art-Union’s bitter rival, the International Art Union) inspired a detailed description and rapturous praise of not only the painting but the genre: it proved the superiority of painting over literature in presenting the many circumstances that comprise one event, and the general public would understand and appreciate its “simplicity and straightforwardness. . . . Who can doubt, in this view of the case, the momentous importance of providing a nation with great works of art, simply as a means of teaching its own history?” In the throes of its enthusiasm, the Art-Union even chided other artists for not undertaking works of similar ambition.[49]

The Bulletin’s art criticism was also shaped by its advocacy of Reynolds’s highest genre. The Art-Union’s 1849 review of the annual exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts reserved its highest praise for Rothermel’s Judgement Scene in the Merchant of Venice (location unknown).[50] A review of the 1850 National Academy of Design exhibition lamented that “we seek in vain for one [artwork] which embodies in a style which is grand, and yet peculiar to its author, some great and universal truth” through US subjects.[51] In 1850 and 1851, the Bulletin introduced illustrations and highlighted subjects such as Leutze’s The Knight of Sayn; Hoppin’s original engraving, Pocahontas Rescuing Captain John Smith;[52] and James W. Glass Jr.’s The Standard in Danger (location unknown) and The Standard at Rest (location unknown), depicting the first battle of the English Civil War of 1642.[53]

While the American Art-Union presented an outward show of support for elevated subjects, it was dogged by the practical contradictions inherent in bringing history painting to its intended mass audience through its scheme of popular patronage. The genre was intended to develop an educated and moral citizenry, which required an institutional owner to put the works on public display. Yet, these history paintings were purchased for private ownership through distribution via an organization built on broad popular appeal. The large, spectacular, attention-getting history paintings that the Art-Union proudly purchased and distributed were too big for most of the awardees to accommodate in their homes, much less display to the public, and the organization began to quietly discourage large-scale works in their letters to artists, particularly from those less well known. The institution’s corresponding secretary, Andrew Warner, explained to one artist that the committee generally did not desire very large pictures “as they are better adapted for galleries than private [homes] where most that are distributed find their way.”[54] He further explained to another artist, “We find after the distribution the larger pictures are offered for sale, so few have suitable apartments to contain them and the result is they are sacrificed at prices for below the original cost, which must have a tendency to injure the artists, and certainly operates as a caution to Art-Unions.”[55]

In 1849, The New York Journal of Commerce (appropriately enough) asserted, “It is very certain that the object of an immense majority of the subscribers is not the encouragement of art, but the winning of a picture, often to be sold as soon as drawn.”[56] The Art-Union’s correspondence includes a number of letters from “winners” of paintings asking about their value, with many directly inquiring whether the Art-Union would resell them on their behalf or buy them back. Warner faithfully replied with amounts paid and explained that repurchasing would be contrary to the Art-Union’s purpose to foster a love of art. He always included a few words praising the picture’s artistic merits, no doubt in the hope of persuading the owner to keep it for his or her own edification and enjoyment.[57] However, attempts at sales can be found: The Ohio Cultivator announced that William Edward West’s Cupid and Psyche (location unknown), won by Mrs. Conrad of Roscoe, Ohio, was valued at $500 or $600 and she would be willing to sell it at a fair price.[58] One member even filed a lawsuit making a claim to Thomas Prichard Rossiter’s The Regicide Judges Succored by the Ladies of New Haven (New Haven Museum, New Haven), a much larger and potentially more valuable painting than the one that had been awarded to him, Charles Baker’s View in Delaware County, New York (location unknown).[59] The member was satisfied when given an affidavit from the officiating secretaries at the distribution, but one wonders whether it was a genuine misunderstanding or a bid for more valuable painting. Attempts to monetize artworks represent only a small handful among nearly 3,000 distributed, and it is impossible to know how many were quickly resold privately, but it is clear that, for at least some members, the appeal of a monetary prize was more attractive than the nobler enjoyment of the work of art itself.

The most prominent example of the pitfalls of distributing a valuable artwork was the case of Cole’s Voyage of Life (figs. 51–54). The four-painting cycle was already known and admired in New York by 1848; the descendants of Samuel Ward, who commissioned the series, had lent it to the New-York Gallery of Fine Arts since 1845, and it appeared in the Cole memorial exhibition in the Art-Union galleries after his untimely death in 1848. In a departure from its policy of buying paintings only from living artists, the Art-Union purchased the group for $2,000, less than half of the original cost of $5,000 (and the Art-Union advertised that it was worth $6,000).[60] While the purchase of the Voyage of Life for the 1848 distribution increased its membership by an order of magnitude (as can be seen in the Membership map from 1847 to 1848), it also contributed to the impression that the institution functioned as a lottery, since awarding paintings that were far too large for most people to keep in their homes made it necessary to sell them, to the “winner’s” significant financial benefit. The Albion reported that at the distribution on the evening of December 22, 1848, at the Broadway Tabernacle every seat was occupied, the aisles were thronged, and even the staircases were “choked up by persons unable to get nearer to the scene of the action. The heat was suffocating and the excitement was intense.”[61] After the drawing for the Voyage of Life, many left. It was awarded to J. T. Brodt of Binghamton, New York. Rumors flew that he had purchased his membership collectively with four friends, and that they rolled dice to determine the owner of the full membership, making the arrangement seem like a lottery within a lottery.[62] He quickly sold it to the Rev. Gorham A. Abbott of the Spingler Institute, a school for young ladies in New York’s fashionable Union Square.

The Internal Face: Unintentionally Building a National Market for Landscape Painting

The American Art-Union’s advocacy of history painting is clear from its public statements and distributed engravings, but its decisive impact on landscape painting is not as easy to discern. In contrast to its stated goals and ideals, a study of its internal records and analysis of its purchases reveals that the institution strongly encouraged and patronized landscapes in order to fill out its offerings with affordable, acceptable quality, universally appealing paintings that middle-class members could display in their homes. The Artworks Distributed by Genre chart breaks down works distributed each year to show that the Art-Union purchased far more landscapes than any other genre, as seen in large green portion of each bar. Hovering over each portion of the bar reveals summary statistics, and clicking on each portion lists the individual works of art. After its first year, more than half were landscapes, peaking at two-thirds in 1845.

Scholarship on the Art-Union has understandably focused on works by better-known figures, but its correspondence is full of exchanges with lesser-known artists. Their letters show that the institution often discouraged aspiring artists from attempting complex historical subjects, particularly those without access to a formal art education, and encouraged them instead to begin with the landscape and the careful study of nature. One of several such exchanges is Warner’s advice to Ohio artist Richard Law Hinsdale (1825–56): “It is bold for an artist so young in years, as well as in his profession as I hear you are, to attempt such subjects without suitable studies, costumes, etc. to aid him in the work.”[63] However, his pictures “are thought to possess evidences of a good deal of talent, and that you exercise it properly by addressing yourself to the study of natural objects.” An undated example of Hinsdale’s work, though not one purchased by the Art-Union (fig. 55), shows that at some point he combined his figural aspirations with landscape. Warner explained to eighteen-year-old Susan C. Waters (1823–1900) of Friendsville, a rural village in northern Pennsylvania, that the works of amateurs were rarely purchased because they must “successfully compete” with professional artists who have devoted years of careful study to their work, and that she should seek out paintings by skillful landscape artists for study.[64] On other occasions, Warner advised artists in New Jersey and Massachusetts to attempt less difficult subjects than the large figural compositions that they had submitted.[65]

Accordingly, the Art-Union encouraged artists who followed its advice. Victor Moreau Griswold (1819–72) was an Ohioan who spent most of his career as a portrait and landscape painter and photographer in that state.[66] Griswold began sending his pictures to the Art-Union in 1849 and his correspondence documents his travails building an artistic career in a small midwestern community. Upon the Art-Union’s purchase of two of his paintings that year, A Road Scene and Sunset after Rain (perhaps similar to The Traveler of 1852, fig. 56), Warner expressed the institution’s pleasure “as much for the merit of the work itself, as to add a new name to our Catalogue of American Artists.”[67] Warner warmly praised Griswold to the local honorary secretary (a volunteer local representative of the Art-Union), calling him “a man of ability” who would “soon become eminent as a Landscape painter.”[68] The many letters between Griswold and Warner show the Art-Union’s intense interest in fostering a young landscapist, particularly one like Griswold who wished to turn away from portraits, the provincial artist’s bread and butter.[69] The two discussed the artist visiting New York to see artworks there, though it is not clear whether the trip came to pass.[70] Griswold enthused that the Art-Union’s “favorable reception of his works” had “added greatly to my reputation [in Tiffin, Ohio]” and would increase his local patronage.[71] But success did not come as easily as he had hoped. Griswold’s letters throughout 1850 describe his struggles to improve his work and his discouragement that he could not hope to compete with the illustrious artists whose work was accepted by the Art-Union. Warner responded with long letters offering advice and encouragement.[72] In spite of the Art-Union’s continued patronage by purchasing a landscape in 1850, Griswold lamented that local sales were poor and “the prospect ahead is terrible.”[73] Perhaps in response to Griswold’s pleas, in 1851 the Art-Union purchased two more landscapes. Griswold continued to paint landscapes for the rest of his professional life, aided by supplemental income from his photography.[74]

The institution’s correspondence shows that the Art-Union also subtly shaped landscape painting to meet the desires of its members through regular calls for “pleasant” and “agreeable” subjects. Warner praised the execution of one artist’s contribution, Man at the Helm, but explained that “It is hardly to be considered a suitable parlor picture (the probable destination of all ours).” Instead, he asked, “Why can you not select some agreeable subject.”[75] In a more quotidian vein, one artist was repeatedly told of the committee’s aversion to large rocks in landscapes.[76] Their concerns were probably not unusual—it is fair to imagine that most buyers of landscapes in the period preferred pleasant scenes. But the Art-Union’s visibility and reach gave its decisions and preferences added weight.

The American Art-Union set itself the task of developing public taste and fostering artists in the United States, and from 1849 through 1851 the Bulletin was full of articles and advice directed toward aspiring artists. Though the institution promulgated history painting as the highest and most esteemed genre of art, most of its didactic articles were aimed toward landscape painting, perhaps because it was the genre most easily learned by correspondence, in the absence of local instruction in figure painting and composition. Articles on aspects of landscape painting, including the merits of watercolor versus oil and how to choose the right type of tree to suit the subject, were extracted from Blackwood’s Magazine, an English periodical.[77] During the summer of 1851, the Bulletin reprinted “The Art of Sketching from Nature,” written and illustrated by Thomas Rowbotham, professor of drawing at the Royal Naval School (fig. 57).[78] It was, wrote the Bulletin, in keeping with their plans to include “articles of practical value, and suited to the wants of beginners,” since it explained linear perspective, where to begin a sketch, and how much of the scene to include.[79] An unsigned article on “The Art of Landscape Painting in Water-Colors” in the Bulletin, which began in the November 1, 1851 issue and concluded in the December 1, 1851 issue, provided information for the beginner, “conveyed in very clear and simple language.”[80] It offered advice and a working method and discussed tools, materials, processes, and techniques.

The Bulletin included a two-part article titled “Some Remarks on the Landscape Art,as Illustrated by the Collection of the American Art-Union” in its November 1849 and December 1849 issues, which went beyond praise to enumerate the Art-Union’s preferences for landscape painting. It charged artists to create “compositions that embody the striking effects of our scenery,” rather than merely copies from nature, and called upon them to be not portrait painters of nature, but rather “teachers of how to view her through the poet’s eye.”[81] Its remarks on Art-Union pictures were not entirely laudatory, and included some criticisms: Church’s Evening after a Storm (private collection) was cited as an example of what artists should not do in making the foreground unsightly or unpleasant. Durand’s contributions, on the other hand, were praised for their skill in making the middle ground “a complete union of the elements.” The article concluded, “we venture to hope that our remarks will have the effect to aid our young landscape artists in their studies.”[82]

The Art-Union’s low-profile but pervasive promotion of landscape painting extended to the works that it purchased for distribution to its members. As the institution grew, so did its power and influence, and its decisions as to what kinds of paintings to purchase were more closely scrutinized. Many of the artists that the Art-Union patronized in quantity can be classified as either “prestige” artists, that is, those whom the institution actively sought for high-profile works that would lend attraction and credibility to their offerings, or from “middle-market” artists, who could be counted on for quantities of well-executed and appealing smaller works for reasonable prices. Prestige artists were solicited for paintings, their studios were visited, their activities were commented upon in the Art-Union’s publications, and their contributions each year were proudly announced and warmly described. As might be expected, they courted such established landscapists as Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand. The Art-Union purchased fifty-three works from Durand and twenty-one from Cole during his lifetime,[83] and it mounted a memorial exhibition for Cole in 1848. The Art-Union also launched the careers of a number of future luminaries of the Hudson River school’s second generation.[84] Jasper Francis Cropsey sold forty-five paintings to the Art-Union from 1843 to 1851. Though price information is not available for each painting, prices for thirty-seven of them total $4,187, the equivalent of nearly $120,000 as of this writing. His contemporary, Sanford Gifford, was first patronized by the Art-Union in 1847. The institution immediately grasped his talent and began to purchase from him steadily, totaling twenty-seven works in four years. In a gesture of confidence, by 1849 the Art-Union offered Gifford $110 for any three pictures he wished to submit.[85] John Frederick Kensett was another favorite of the Art-Union, which purchased forty-four of his paintings. Known prices for thirty-eight of them total $3,567, the equivalent of over $95,000 today. Perhaps the best-known young beneficiary of the Art-Union’s patronage was Frederic Edwin Church. From 1847 to 1851, the institution purchased twenty-eight of his paintings. Price information is available for twenty-seven of them, and they total a remarkable $4,300. Church’s contributions are particularly notable because they included some of his major early works, such as Above the Clouds at Sunrise (private collection), Twilight, “Short Arbiter ’twixt Day and Night,” (Newark Museum, Newark), and New England Scenery (George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum, Springfield).

Those that can be characterized as middle-market artists could be depended upon for large quantities of acceptable work at reasonable prices. The Art-Union developed relationships with artists in various genres whose names are little known today. One example was English-born John Thomas Peele, who painted sentimental scenes often featuring children, a type of idealized genre painting that was popular during the Victorian period but is studiously neglected today (see fig. 58 for a representative example that was not purchased by the Art-Union). From 1846 to 1851, Peele sold twenty-five paintings to the institution at a respectable average price of $155. Peele was based in New York City until he returned to England in late 1851 or early 1852, just when the Art-Union entered the troubled period that would herald its demise after the New York Supreme Court judged it to be an illegal lottery.[86] James W. Glass Jr., born in Spain to English and US parents, studied briefly with Daniel Huntington before launching on a specialty that might be termed small-scale history paintings. He produced large numbers of modestly scaled subjects from literary sources and English history (see fig. 59 for a representative example).[87] In five years, from 1846 to 1851, forty-eight of his works were purchased at an average price of nearly $150, more than $4,000 today.

Despite its rhetoric on elevated subjects, the Art-Union encouraged and became dependent upon landscapes to fill its roster for each year’s distribution.[88] Warner made its requirements clear when he instructed one artist, “We have already purchased a great many high-priced paintings and desire to increase our list without increasing the average price.”[89] A handful of painters provided numerous small landscapes, such as DeWitt Clinton Boutelle, born in Troy, New York, and working in New York City by 1846. He was influenced by the work of Cole and Durand and became an associate member of the National Academy of Design.[90] He sold seventy-one landscape paintings to the Art-Union from 1845 to 1851 in the style of Untitled (Hudson River Landscape with Indian) (fig. 60). Though his paintings ranged in size, his average price was about $48, lower than that of Peele’s and Glass’s figure paintings.

Similarly, Walter Oddie contributed numerous small landscapes. Though his name is unfamiliar today, Oddie built a prosperous landscape career in the antebellum era.[91] Largely self-taught, he can be considered a successful example of the Art-Union’s advice to aspiring artists to study nature and pursue landscape subjects. The Art-Union purchased a remarkable sixty-two paintings from him from 1842 through 1851, probably similar to Fishing by the Hudson River (fig. 61). For works where payment information is known, he received an average of $42, mostly for very small landscapes measuring 10 by 14 inches. Several times, Oddie offered a number of landscapes at once for about $125. Oddie seems to have understood the institution’s interest in quantities of domestically scaled, low-priced landscapes, in keeping with their rhetoric about art “for the people” and national subjects. Pragmatic perhaps to the point of cynicism, nearly half of his paintings were simply titled Landscape.

The Art-Union’s purchases from middle-market artists affected how they worked. As described above, the Art-Union often found itself in need of large quantities of paintings at low prices, and some began to submit swaths of paintings. In its later years, many of the artworks that the Art-Union declined were by artists who had submitted multiple works and some, but not all, were purchased.[92] For instance, Boutelle inundated the institution with landscapes. In 1849, he explained, “Understanding your Picture list is not complete, and knowing you want small as well [sic] low priced ones, ‘I have three more of the same sort left.’” He offered them for the modest price of $75 for the group.[93] Boutelle himself couched his “I have three more” comment in quotation marks, as if it was a characteristic phrase he used often with the Art-Union. He admitted, perhaps a little sheepishly, “The artist lacking Patrons and Friends sufficiently wealthy to purchase his works—looks to you perhaps too often for that patronage by which he derives his support.”[94] Other middle-market landscapists, such as William Rickarby Miller and Christopher P. Cranch, also submitted large numbers of paintings.[95] Even the promising young Kensett submitted a number of small, modestly priced pictures at the end of November 1849, shortly before the annual distribution, and most were purchased.[96]

The Art-Union’s support for landscapes also inspired artists who might not have otherwise embraced the genre. Daniel Huntington is now remembered as an accomplished painter of portraits and ideal subjects, and the Art-Union encouraged the young man’s high aspirations; as discussed above, the institution chose his A Sibyl as an engraving for 1847, and in 1848 the organization gave him a $1,000 commission for Queen Mary Signing the Death Warrant of Lady Jane Grey (location unknown). However, of the forty-three paintings they purchased from him, thirty-four were landscapes, probably similar to A Swiss Lake of 1849 (fig. 62), which met the institution’s more practical needs. The combination of large and accomplished history paintings and a number of more modestly sized and priced landscapes made him the Art-Union’s most favored artist, earning $6,533, primarily between 1846 and 1850.

One of the most serious complaints that artists brought against the Art-Union—and one of the most difficult to verify—is that they exploited artists working in all genres by routinely paying prices well below market value.[97] The Art-Union asked that artists submitting works for purchase include their asking prices, and the institution often responded with a lower purchase price. In 1849, The Home Journal reprinted a letter from one artist to another (both unidentified), advising that if he submits a painting worth $125 to the Art-Union, they will likely not give him more than a quarter of its value. The article also told of a noted landscape painter who offered a painting for $200 and was offered $50 including the frame, which cost him $20.[98] In spite of the Art-Union’s frequent patronage, Oddie too sometimes expressed discontentment: “On one occasion at least I would be pleased if my valuation could meet your views.”[99]

In the past, it was prohibitively difficult to perform a comprehensive and mathematically based analysis of Art-Union prices due to the difficulty of compiling information scattered among the Art-Union’s voluminous papers and putting them into a usable form. The seminal publication on the organization, American Academy of Fine Arts and American Art-Union of 1953, includes a table with annual averages derived from the total amount paid divided by the number of works distributed. It shows that the average price rose and fell with the institution’s early travails, starting at $85.70 and dipping to a low of $57.50 in 1842, then growing steadily to $104.40 by its final year.[100] While such broad generalizations can be useful, they cannot take into consideration the vast price differences between large and small works, sketches versus complex subjects, and whether the artist was a new aspirant or an accomplished master.

The relatively recent advent and adoption of databases allows for a quantitative investigation of prices paid versus the prices proposed by artists, where the information exists. The chart breaking down artworks each year by genre includes those figures, as well as the underlying data that comprises each average, including artist, title, price offered, and price paid. Overall, the average price paid was about $20 less than the price asked by the artist. This is true of many landscape painters, such as Boutelle, Church, Cropsey, Régis Gignoux, and Fitz Henry Lane. Several others received about $10 less than the price they asked; the smaller gap may indicate either the Art-Union’s greater esteem for the artist or that their prices in general were lower. Examples include marine specialists James E. Buttersworth and James Hamilton, Cranch, Gifford, Kensett, Jervis McEntee, Miller, Oddie, and William Louis Sonntag. As might be expected, the average price paid for history paintings was the highest of any genre. It was triple the average for landscapes from 1848 to 1851. Genre scenes usually found a middle ground at around half the average price paid for history paintings.[101]

These figures are difficult to interpret given the lack of contextual information. While much data has been gathered and insightfully presented on the late nineteenth-century art market, few records exist of prices paid in the antebellum period.[102] For instance, it might be hoped that the National Academy of Design would be a source of comparable prices, but its catalogues do not include them; rather, they ask interested parties to apply to the superintendent to discuss a purchase. The information that can be found is largely anecdotal and limited to well-established artists who commanded the best prices. Records of Durand’s and Kensett’s work offer some clues. Durand, an established and respected artist by the 1840s, was paid $400 for his An Old Man’s Reminiscences of 1845 (38 by 58 in.; Albany Institute of History and Art) and $300 for the slightly smaller Kindred Spirits of 1849 (44 by 36 in.; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR).[103] Kensett’s painting career was just beginning, and by the late 1840s his private patrons paid $50–60 for smaller works and, in a few cases, $250–300 for larger canvases.[104] Another important point of perspective can be found in salaries paid for other occupations during the period. In 1850 in the mid-Atlantic region, the annual salary of the average artisan was $444, that of the average clergyman was $600, and the average lawyer earned $1,400.[105] By this measure, the Art-Union’s purchases alone (without the additional private patronage the institution hoped to encourage) provided the equivalent of a well-paid white-collar job for a number of artists.

The Art-Union, however unintentionally, created a market for a specific kind of artwork. The Morning Courier viewed it through a positive lens, pointing out that one of the best features of the collection was the inclusion of many small pictures by esteemed artists whose larger works could not be purchased in quantity, and thus they would be more widely disseminated. These were “sure to be more acceptable to the members generally: every one knows [what to do with] a little gem, but many would be puzzled where to hang a large picture, with figures or trees half the size of life.”[106] But others were more skeptical of the quality of works that the Art-Union encouraged. The Knickerbocker expressed concern that “men and boys . . . who could not live a week on the productions of their pencils, have supplicated successfully for the admission of their crude efforts, which evince no talent and no genius” and suggested that the organization should pay higher prices for good pictures rather than increase the numbers for the distribution at the lowest possible prices, since in the current system pictures were “hurriedly finished because they are not amply paid for.”[107] The Literary World worried that as the Art-Union grew, demand for pictures would exceed supply and “pictures will be, in consequence, manufactured on the very cheapest principal to meet it. We fear we shall have more paintings and less excellence.”[108] Like The Knickerbocker, they recognized the economic incentives at play when they warned the institution to buy fewer pictures and pay better prices, or “the Art-Union is destined to become the nurse of mediocrity; it may benefit artists in a pecuniary view, but art will suffer in proportion. . . . We all know what cheap literature is, and cheap oyster houses—defend us from cheap Art.”

In spite of legitimate concerns about the unexpected market created by the Art-Union’s well-intentioned plan, the organization created a national awareness of and appreciation for the country’s art. A supporter in Albany observed,

In every country village which I have visited of late where the bulletins and engravings have been received, I find the inhabitants discussing not only their merits, but also those of other works of art and, moreover, there appears also a very creditable willingness to patronize both the Art Union, and such artists as are deserving of their patronage; and what makes this of more interest, is that this is true of places where the interests of art have never before been recognized.[109]

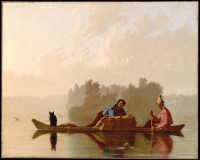

Enthusiastic notices of the Art-Union’s activities appeared in newspapers across the country, including the Arkansas State Gazette, The Charleston Courier, the Alabama Journal, The Ohio Statesman, the New Orleans Daily Picayune, and the Maine Farmer.[110] The delivery of engravings to members in smaller towns was a major cultural event; in July 1846, the Morning News in New London, Connecticut, reported that the engraving for 1845 had been received at the newspaper office and “the Ladies are particularly invited to call and inspect it.”[111] In fact, the engravings inspired cottage industries exploiting their popularity: The Ohio Statesman ran an advertisement offering “a fine assortment of Gilt and Rosewood Frames for the ‘Engravings of the American Art Union.’”[112] Members in towns across the country were in just as much suspense as those present for the distribution of original artworks each December, and they were keenly interested in whether a prize was awarded in their area. Newspapers often noted whether a work of art had been drawn for a local member in communities such as Albany, New York; Baltimore, Maryland; New Bedford, Massachusetts; and New Orleans, Louisiana; as well as other towns in Maine, Minnesota, Ohio, and Vermont.[113] One notable example is Bingham’s Fur Traders Descending the Missouri, which was awarded to Robert S. Bunker in Mobile, Alabama (fig. 63).[114] It epitomizes the Art-Union’s ability to connect artists and potential patrons across the country, in this case bringing an important work by a renowned Missouri artist to a member in the South, via New York City.

Landscape as “the Truest Field”

The early history of the United States’ art world is defined by the unique anxiety of a nation which, though young, compared its culture to that of its European counterparts, which had been developing the mechanisms for the creation, evaluation, display, and sale of art for centuries. The Art-Union was a much-needed, if temporary measure to jumpstart a country whose cultural aspirations far outstripped its rudimentary ability to fill them. Robert K. Merton’s theory that complex systems can produce surprising results, discussed above, attributed unintended consequences to several causes. Among them is a lack of complete knowledge that makes it impossible to anticipate outcomes. In the American Art-Union’s case, during its nascent period all parties lacked experience, but they also shared a sense of possibility and idealism that encouraged experiments that produced mixed results. Another cause Merton identified was immediate needs overriding long-term interests. For the Art-Union, the institution’s stated long-term goal of promoting history painting was quietly overtaken by its need to attract members with large numbers of domestically scaled and affordable landscapes.

Art historian Angela Miller has noted that the ascendancy of the landscape genre in the nineteenth-century United States coincided with the emergence of a middle class and a “nationwide market-based entrepreneurial economy.”[115] Her description hints at the tie between landscape and the middle class that was facilitated by the Art-Union. The map of works distributed shows how artworks were sent throughout the country, color coded by genre. The preponderance of green demonstrates the large number of landscapes that found their way into homes nationwide. After the first few bumpy years, the distribution of genres was surprisingly stable, with an average of 20 percent genre scenes from everyday life, 9 percent history paintings, and 52 percent landscapes each year.

Merton’s theory is commonly understood to result in three types of unintended consequences.[116] The “perverse result,” an effect contrary to what was originally intended, certainly describes the Art-Union’s overt and covert support of different genres of art and its paradoxical results. The other two unintended consequences, the “unexpected drawback” and the “unexpected benefit,” characterize how the Art-Union created a demand for small landscapes that some considered subpar, but they also explain how dispersing them spread enthusiasm for this neglected genre across the country. The Membership map establishes the American Art-Union’s scope and influence, which is also seen in the representation of landscapes in both the Works Distributed map and the Artworks Distributed chart.

Though the United States’ landscape movement began in the 1820s, the American Art-Union spurred its momentum, not only by supporting and publicizing the great names of the Hudson River school, but also by creating a large demand for landscape painting that was filled by artists across the country and enjoyed by Art-Union members nationwide. In so doing, the institution expanded the landscape school from an East Coast–centered phenomenon to a truly national movement. In 1849, the Art-Union acknowledged landscape as part of its offerings, but continued to give history pride of precedence, announcing that “Paintings have found purchasers: public taste has been not only improved but discovered: the easel has been in demand: subjects natural to our country, its history, its scenery, and its people, have been illustrated. Perhaps, indeed, we may have been instrumental in founding an American School.”[117] However, that same year The Literary World examined the Art-Union’s Free Gallery exhibition and discerned the true results of its practices, calling the nation’s scenery “the truest field for our true Artists.”[118]

Epigraph: Lydia Maria Child, Letters from New York (New York: C.S. Francis & Co., 1845), 218–19.

[1] Robert K. Merton, “The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action,” American Sociological Review 1, no. 6 (December 1936): 894–904.

[2] Mary Bartlett Cowdrey, American Academy of the Fine Arts and American Art-Union, 1816–1852 (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1953), 216.

[3] Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), xxi.

[4] David M. Potter, The Impending Crisis: America Before the Civil War, 1848–1861 (1976; repr., New York: Harper Perennial, 2011), 52–53.

[5] “The American Art-Union,” The Knickerbocker 32, no. 5 (November 1848): 442.

[6] Cowdrey, American Academy of the Fine Arts and American Art-Union, 1816–1852. The index is combined with that of the American Academy of the Fine Arts (1802–42).

[7] Maybelle Mann, The American Art-Union (Otisville, NY: ALM Associates, 1977); Maybelle Mann, The American Art-Union (Jupiter, FL: ALM Associates, 1987).

[8] Wendy Greenhouse, “The American Portrayal of Tudor and Stuart History, 1835–1865” (PhD diss., Yale University, 1989), 56.

[9] Carol Troyen, “Retreat to Arcadia: American Landscape and the American Art-Union,” American Art Journal 23, no. 1 (1991): 31.

[10] Christopher Carroll Oliver, “‘Elevated and Pure Public Taste’: The Membership Prints of the American Art Union, 1840–1851” (MA thesis, University of Virginia, 2008), 5–6.

[11] Rachel N. Klein, “Art and Authority in Antebellum New York City: The Rise and Fall of the American Art-Union,” Journal of American History 81, no. 4 (1995): 1538–41.

[12] Joy Sperling, “‘Art, Cheap and Good:’ The Art Union in England and the United States, 1840–60,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 1, no. 1 (Spring 2002), accessed February 24, 2014, http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/.

[13] Patricia Hills, “The American Art-Union as Patron for Expansionist Ideology in the 1840s,” in Art in Bourgeois Society, 1790–1850, eds. Andrew Hemingway and William Vaughn (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 314–16, 322.

[14] Amanda Lett et al., Perfectly American: The Art-Union and Its Artists, exh. cat. (Tulsa, OK: The Gilcrease Museum, 2011).

[15] For a finding aid, see “Guide to the Records of the American Art Union,” New-York Historical Society, accessed October 4, 2018, http://dlib.nyu.edu/.

[16] Followed by animal subjects and still lifes. See Joshua Reynolds, Discourses on Art (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1975).

[17] Transactions of the Apollo Association (New York: Charles Vinten, 1841), 9–10.

[18] American Art-Union. Transactions for 1847 (New York: G. F. Nesbitt, 1848), 22, 26.

[19] “What Has the American Art-Union Accomplished?,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 2, no. 7 (October 1849): 11.

[20] “An Engraving,” The Evening Post (New York), May 1, 1841, 2; the legend was perpetuated in Mason Locke Weems’s hagiographic and not entirely reliable biography, The Life of General Francis Marion (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1860), 153–56.

[21] No details have been found on why the committee felt that artists’ submissions fell short, nor a list of works submitted.

[22] “Apollo Association,” The New World, May 20, 1843, 605.

[23] Management Committee Minutes, vol. 1, April 8, 1844, American Art-Union Records, New-York Historical Society, New York [hereafter N-YHS].

[24] Management Committee Minutes, vol. 1, December 26, 1844, American Art-Union Records, N-YHS.

[25] John P. Ridner to artists, February 2, 1844, reel 41, Letterpress Books, American Art-Union Records, N-YHS [hereafter Letterpress Books]; John P. Ridner to W. S. Mount, February 1, 1844, William Sidney Mount Papers, 1833–1868, N-YHS.

[26] “The Fine Arts. Art-Union,” The Literary World, July 10, 1847, 540.

[27] Management Committee Minutes, vol. 1, May 26, 1846, American Art-Union Records, N-YHS.

[28] “Fine Arts. The Art Union,” The Home Journal, December 26, 1846, 3; American Art-Union. Transactions for 1847 (New York: G. F. Nesbitt, 1848), 6.

[29] Jay Cantor, “Prints and the American Art-Union,” in Prints in and of America to 1850, ed. John D. Morse (Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia, 1970): 307.

[30] “[Correspondence.] To the Committee of Management of the American Art Union,” The Literary World, May 15, 1847, 348; “The Fine Arts. The Art-Union,” The Literary World, October 16, 1847, 257.

[31] Transactions of the American Art-Union for the Year 1848 (New York: G. F. Nesbitt, 1849), 45.

[32] Management Committee Minutes, vol. 2, June 1, 1848, American Art-Union Records, N-YHS.

[33] Management Committee Minutes, vol. 3, January 16, 1851, American Art-Union Records, N-YHS.

[34] After it was established as the American Art-Union, the organization prohibited portraits in order to encourage artists to attempt other genres.

[35] The American Art-Union purchased engravings after Emanuel Leutze’s George Washington Crossing the Delaware for the few members who subscribed for 1852.

[36] Management Committee Minutes, vol. 3, November 8, 1849, American Art-Union Records, N-YHS.

[37] Potter, The Impending Crisis, 90–122.

[38] Howe, What Hath God Wrought, 744–91.

[39] Executive Committee Minutes, vol. 2, May 23, 1850, American Art-Union Records, N-YHS. On Leutze’s The Knight of Sayne, see “Emanuel Gotlieb Leutze,” The Knohl Collection, accessed October 22, 2018, http://www.theknohlcollection.com/.

[40] Management Committee Minutes, vol. 3, November 3, 1851, American Art-Union Records, N-YHS.

[41] “To the Friends of the American Art-Union,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 2, no. 7 (October 1849): 5; “Some Remarks on the Landscape Art, as Illustrated by the Collection of the American Art-Union, No. II,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 2, no. 9 (December 1849): 15–19.

[42] “What Will the American Art-Union Accomplish?,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union, 2, no. 8 (November 1849): 9–10.

[43] Cowdrey, American Academy of the Fine Arts and American Art-Union, 1816–1852, 255.

[44] “Chronicle of Facts and Opinions,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 5 (August 1850): 81–82.

[45] The Three Marys at the Sepulchre has not been located and The Deliverance of St. Peter may have never been finished. See Wendy Greenhouse, “Daniel Huntington and the Ideal of Christian Art,” Winterthur Portfolio 31, no. 2/3 (Summer–Autumn 1996): 112–13.

[46] “Fine Art Gossip,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 2, no. 1 (April 1849): 11, 20–21; “The Gallery—No. 3,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 2, no. 4 (July 1849): 7–8.

[47] “The Chronicle,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 6 (September 1851): 95–96.

[48] “Fine Art Gossip,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 2, no. 7 (October 1849): 25–26; “Chronicle of Facts and Opinions,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 2 (May 1850): 30–32; “Chronicle of Facts and Opinions,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 7 (October 1850): 117–18; “Chronicle of Facts and Opinions,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 8 (November 1850): 138–39.

[49] “The Chronicle,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 8 (November 1851): 131.

[50] “The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 2, no. 5 (August 1849): 6–7.

[51] “The Exhibition of the National Academy,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 2 (May 1850), 20–21.

[52] “Chronicle of Facts and Opinions,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 4 (July 1850): 64–65.

[53] The Standard in Danger and The Standard at Rest (illustrations), Bulletin of the American Art-Union 1 (April 1850): n.p., following p. 15.

[54] Andrew Warner to J. Cameron, October 31, 1850, reel 54, Letterpress Books.

[55] Andrew Warner to G. Grunewald, April 7, 1849, reel 48, Letterpress Books.

[56] Randy Ramer, “Free to the World: The Art-Union Gallery,” in Lett et al., Perfectly American, 122, quoted from New York Journal of Commerce, January 1849. The comment also appeared in “American Art Union,” Daily Evening Transcript (Boston, MA), January 25, 1849, 3.

[57] Andrew Warner to G. W. Penney, January 9, 1850, reel 51, Letterpress Books; Joseph Perkins to Andrew Warner, February 11, 1851, reel 7, Letters from Artists, American Art-Union Records, N-YHS [hereafter Letters from Artists]; Management Committee Minutes, vol. 1, January 26, 1846, American Art-Union Records, N-YHS; G. B. Ripley to American Art-Union, December 13, 1848, reel 4, Letters from Artists; E. Parmele to Asher B.Durand, June 4, 1852, reel N20, frames 693–94, Asher Brown Durand Papers, 1812–1883, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; Andrew Warner to J. P. Waters, January 29, 1850, reel 51, Letterpress Books; Andrew Warner to J. B. Cooper, December 24, 1850, reel 56, Letterpress Books; Andrew Warner to S. J. Cooke, January 5, 1850, reel 5, Letters from Artists; Andrew Warner to F. A. Gerrish, April 1, 1851, reel 57, Letterpress Books.

[58] “The Traveling Editor Abroad,” The Ohio Cultivator (Columbus, OH), November 15, 1851, 344. The painting was recently sold by Sumpter Priddy III. See “William Edward West, Cupid and Psyche,” InCollect, accessed October 22, 2018, https://www.incollect.com/.

[59] Management Committee Minutes, vol. 2, March 7, 1849, American Art-Union Records, N-YHS.

[60] Paul D. Schweizer, Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life (Utica, NY: Munson Williams Proctor Arts Institute, 2014), 52–55. See also Transactions of the American Art-Union for the Year 1848 (New York: G. F. Nesbitt, 1849), 46; Advertisement, The Literary World, November 11, 1848, 824.

[61] “The American Art-Union,” The Albion, December 30, 1848, 633.

[62] “How Mr. Brodt Happened to Draw the Large Prize at the Art Union Distribution,” Telescope (Manchester, NH), January 20, 1849, 3; “Was it Gambling?,” Plain-Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), January 30, 1849, 2; “American Art Union,” Daily Evening Transcript (Boston, MA), January 25, 1849, 3.

[63] Andrew Warner to R. L. Hinsdale, December 10, 1848, reel 4, Letters from Artists.

[64] Andrew Warner to S. C. Waters, June 20, 1851, reel 35, Letterpress Books.

[65] Andrew Warner to J. Whitehead, September 27, 1849, reel 49, Letterpress Books; Andrew Warner to W. A. Wall, September 7, 1849, reel 49, Letterpress Books.

[66] Jeffrey Wiedman et al., Artists in Ohio, 1787–1900: A Biographical Dictionary (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2000), 355–56.

[67] Andrew Warner to V. M. Griswold, October 10, 1849, reel 46, Letterpress Books.

[68] Andrew Warner to Dr. R. Hills, November 14, 1849, reel 50, Letterpress Books.

[69] V. M. Griswold to Andrew Warner, June 11, 1850, reel 5, Letters from Artists.

[70] V. M. Griswold to Andrew Warner, October 1, 1849, reel 5, Letters from Artists; Andrew Warner to V. M. Griswold, July 9, 1851, reel 58, Letterpress Books.

[71] V. M. Griswold to Andrew Warner, January 10, 1850, reel 6, Letters from Artists.

[72] Andrew Warner to V. M. Griswold, February 23, 1850 and April 25, 1850, reel 52, Letterpress Books. Griswold acknowledged Warner’s kindness in his letter of March 4, 1850, reel 5, Letters from Artists.

[73] V. M. Griswold to Andrew Warner, July 29, 1850, reel 6, Letters from Artists.

[74] Wiedman et al., Artists in Ohio, 1787–1900, 356.

[75] Andrew Warner to L. G. Sellested, January 21, 1850, reel 51, Letterpress Books.

[76] Andrew Warner to G. Grunewald, April 7, 1849 and April 20, 1849, reel 48, Letterpress Books.

[77] “Landscape Painting,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 7 (October 1850): 112–14; “Autobiography of John Burnet,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 8 (November 1850): 133.

[78] “The Art of Sketching from Nature,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 4 (July 1851): 53–55; “The Art of Sketching from Nature, Continued,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 5 (August 1851): 69–71; “The Art of Sketching from Nature, Concluded,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 6 (September 1851): 85–87.

[79] “The Art of Sketching from Nature,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 4 (July 1851): 53–55.

[80] “The Art of Landscape Painting in Water Colors,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 8 (November 1851): 119–23; “The Art of Landscape Painting in Water Colors, Concluded,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 9 (December 1851): 139–43.

[81] “Some Remarks on the Landscape Art, as Illustrated by the Collection of the American Art-Union,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 2, no. 8 (November 1849): 21–22.

[82] G. W. P., “Some Remarks on the Landscape Art, as Illustrated by the Collection of the American Art-Union, No. II,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 2, no. 9 (December 1849): 19.

[83] Cole’s Dream of Arcadia and the Voyage of Life were purchased from their owners after Cole’s death.

[84] The Art-Union similarly encouraged the early work of Jervis McEntee, George Inness, and Régis Gignoux.

[85] S. R. Gifford to Andrew Warner, December 9, 1849, reel 5, Letters from Artists.

[86] David Dearinger, ed., Paintings and Sculpture in the Collection of the National Academy of Design, vol. 1, 1826–1925 (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 2004), 439–40.

[87] Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, American Paintings Before 1945 in the Wadsworth Atheneum, vol. 2 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996), 412.

[88] Other landscape painters whose works were purchased in quantity were Gustavus Grunewald, William B. McConkey, and Thomas A. Richards.

[89] Andrew Warner to G. Grunewald, November 15, 1849, reel 50, Letterpress Books.

[90] George C. Groce and David H. Wallace, The New-York Historical Society’s Dictionary of Artists in America, 1564–1860 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1957), 69.

[91] See Annette Blaugrund, “‘The ‘Mysterious Mr. O.’: Walter Mason Oddie (1808–1865),” The American Art Journal 12, no. 2 (Spring 1980): 60–77.

[92] See Register of Works of Art, American Art-Union Records, N-YHS.

[93] D. C. Boutelle to American Art-Union, December 20, 1849, reel 5, Letters from Artists.

[94] D. C. Boutelle to American Art-Union, October 7, 1846, reel 11, Letters from Artists.

[95] Though the Art-Union did not purchase all of the works they submitted, it did purchase thirty-two paintings and watercolors from Miller and twenty-seven from Cranch.

[96] J. F. Kensett to American Art-Union, November 29, 1849, reel 5, Letters from Artists.

[97] Most recently, see Peter John Brownlee, “The American Art-Union: Blank or Prize?,” in Lett et al., Perfectly American, 85.

[98] “Business Position of Artists,” Home Journal, November 10, 1849, 2.

[99] W. M. Oddie to American Art-Union, August 19, 1851, reel 7, Letters from Artists.

[100] Cowdrey, American Academy of the Fine Arts and American Art-Union, 1816–1852, 161.