The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

German art historian Gustav Friedrich Waagen (1794–1868) was an unusual visitor among the privileged few who were granted access to the prestigious art collections held in private homes throughout England in the middle of the nineteenth century.[1] He brought scientific flair to what was usually the domain of connoisseurship and cultivated dilettantism based on the potential for social prestige associated with the works of art on display. A close collaborator of Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835), Waagen was a staunch proponent of the ideals of the Enlightenment, most particularly of the spiritual and moral improvement of man through art. Appointed director of the Berlin Gemäldegalerie in 1830, he proposed that the main role of the museum, which he saw as a public institution at the heart of a national cultural discourse, should be to convey the artworks’ pedagogical value. This was the guiding principle behind his choices regarding the museum’s acquisition policies and the display of its collections. In this respect, as James Hamilton recently wrote, Waagen possessed “an acquisitiveness for the public benefit that anticipated both a national glory and a humane civic outcome.”[2]

In pursuit of this goal for his museum, Waagen travelled around Europe to take the pulse of the art world of his time, seeing as many originals as he could and compiling a comprehensive survey of major art collections, both public and private. England especially attracted him because of “the astonishing treasures of art of all descriptions which this island contain[ed].”[3] Similarly enthusiastic appreciations were common in the travel writing of contemporary artists and connoisseurs. American painter John Trumbull (1756–1843), for instance, claimed that “England has had, perhaps, the greatest share in gathering up these scattered Treasures and, by affording a Sanctuary to the Fine Arts, has constituted within herself an Emporium of Wealth, incalculable.”[4] The economic connotations of the word “treasure” assigned to art the double nature of an object signifying tangible prosperity, as well as its usual meaning as an intangible symbol of spiritual elevation. This raised the question of who actually owned these valuable possessions: the individual collectors who purchased them or the British nation as a collective, which found its cultural resonance enhanced through the presence of these artworks on its soil. Also relevant to the matter of art ownership was the question as to how this “embarras de richesses”[5] was used and consumed, and of the place it occupied in the collector’s life and in the lives of those who were privileged enough to be introduced to it.[6]

Waagen’s writings served to broaden the audience for these artworks, which had previously been “hidden from public view,”[7] by presenting them in the form of a musée imaginaire. Based on his notes and on letters to his wife, his work was composed of three volumes in German, published between 1837 and 1839 and entitled Kunstwerke und Künstler in England und Paris (Works of Art and Artists in England and Paris). The English translation by Lady Elizabeth Eastlake (1809–93)—who was married to Charles Eastlake (1793–1865), director of the National Gallery—was published in two volumes between 1854 and 1857 under the title Treasures of Art in Great Britain. Applying the same philosophy that guided his directorial activities at the Gemäldegalerie, Waagen conceived his task of compounding the artistic possessions of the wealthiest countries in Europe as being essential for the formation of a global vision of the Western artistic canon, which should echo the canon displayed in the museum. The Eastlakes similarly campaigned to introduce to England the modern museum practices that had been developed in German-speaking territories—most particularly in the recently opened National Gallery (1824)—a practice of which Waagen was an important representative.[8] His books, in their German version, were instantly integrated into an already flourishing tradition of academic writing about art, which set the pace for the institutionalization of the discipline in the German states, where nurturing and preserving an artistic heritage was an important component of the national psyche. In their translation for a British audience (as represented by the readership of the Art Journal, a publication that regularly promoted Waagen’s expertise), they additionally functioned as a mirror held before a group of art connoisseurs that was not as yet aware of its belonging to a cultural collective. Therefore, they captured a transitional moment when a growing number of private owners considered that they had been entrusted with England’s “emporium of wealth” in the name of the nation and dealt with their collections accordingly.[9] Private taste had public resonance, as it created a positive image of a cultured nation, endowed with an acute feeling for art.

The historiography of collecting regularly highlights Waagen’s role in the transition of art from private to public space in his country, his influence on the curating of public galleries in Britain, as well as the part he played in the Manchester Art Treasures exhibition of 1857.[10] This article proposes to focus on Waagen’s account of private collections in the context of a recently reactivated field of study—the presence of art in the domestic sphere—developing on Giles Waterfield’s 1995 survey of London town houses as galleries of art from the mid-eighteenth to late-nineteenth century.[11] This is an aspect only tangentially tackled in the literature on Waagen; yet it could be equally instructive when trying to reconstitute Victorians’ attitude to art, and to analyze the dialectics between private taste and public statement created by the exhibition of art in the home as it played out in Treasures of Art. By applying the same methods of observation and assessment developed for public museums and galleries onto the realm of English domesticity, Waagen portrays collectors who cultivated a private interest for art as patrons and as curators in the public eye. However, these descriptions of exhibition spaces also reveal the resilience, on the part of the aristocracy in particular, of a sense of ownership and social privilege attached to their collections. Alongside these collectors from the nobility, Waagen’s catalogue also introduces a new generation of wealthy patrons from the middle class who were keen to complement their social ascent through the enhancement of their cultural prestige as art connoisseurs.

The Professional Eye in the Domestic Space

In his 1824 book Memoirs of Painting, William Buchanan (1777–1864) notes the eagerness of British aristocrats to acquire the best pieces in the Orléans sale, which remained the main source of the most prestigious British collections and which represented a watershed in the evolution of British taste for the old masters.[12] Even though these works of art were purchased privately and destined to be enjoyed in the confines of aristocrats’ homes, Buchanan, who took great pride in his achievements as an art dealer who brought artworks into the nation, saluted this movement as an expression of patriotism and dedicated his Memoirs “to those who delight in seeing their country become the seat of the Arts and Sciences, and the reign of George the Fourth rival the period of Lorenzo de Medici.”[13] Similarly, in the introduction to Treasures of Art Waagen writes that the taste and munificence of private individuals surpassed government patronage as regards drawings and as regards pictures “totally outstripped it.”[14]

There were, of course, other popular books describing the art held in the private collections that were sometimes open to the public: for instance, Johann Passavant’s Tour of a German Artist (1836), to name another German visitor, or, focusing specifically on London, Anna Jameson’s Companion to the Most Celebrated Private Galleries of Art in London (1844).[15] There is a crucial difference between Passavant (1787–1861), whose writings on art were still anchored in the romantic tradition, and Waagen, who intended to surpass him and create a language suitable for the emerging discipline of Kunstwissenschaft, or “science of art.”[16] Similarly, Jameson’s book differs from Waagen’s in the level of scholarship that it aspired to, regularly quoting Kunstwerke und Künstler as the most reliable source on matters of attribution. Very lyrical in tone, humbly calling itself a “companion” and not a “guide,” its aim was mainly to convey aesthetic impressions.

According to Anna Jameson (1794–1860), the roles ascribed to artworks within the home, whether symbolic or concrete, were a matter of personal choice: “Pictures are for use, for solace, for ornament, for parade; – as invested wealth, as an appendage of rank.”[17] On the other hand, when Waagen refers to collectors as “true lovers of art,”[18] it has the added implication that they strove to be worthy of their incumbent task of preserving the art by behaving and thinking like curators. Thus, even within the domestic space, visual arts usually worked as a social indicator. Private collections were regularly open to the public, a tradition started by Thomas Hope (1739–1831) in his London house in 1804, after he witnessed the success of public viewings in Paris.[19] French influence can also be discerned in the Marquess of Stafford’s “innovative and farsighted” decision to do the same at Cleveland House in 1806.[20] The gallery was officially inaugurated on May 8, 1806, in the presence of the Prince of Wales, and became known—for want of a local equivalent to the French museum before the formation of the National Gallery in 1824—as “the Louvre of London.”[21] When they were consented to by private collectors, however, these open viewings were organized “on specified days for ticketed individuals.”[22] The rest of the time, as Passavant experienced, access to the artworks in private collections was limited to those “known to some members of the family, or otherwise [able to] produce a recommendation from some distinguished person, either of noble family or of known taste in the arts.”[23]

Waagen was indeed armed with such prestigious letters of introduction from members of the Prussian aristocracy and royalty; he was, for instance, recommended to the Duke of Devonshire by Princess Louisa and Prince Charles of Prussia.[24] His reports on each visit are full of deference for the British collectors who let him in to see their possessions: “Not a day passes that I am not gratified by an introduction to admirable works of art, or eminent men.”[25] This juxtaposition of art owners and their collections is reflected in the structure of Treasures of Art, which is at once a catalogue of objects and a collective portrait of British gentlemen as curators. Waagen’s catalogue captures a rising phenomenon, “in which ownership and public display of art should be regarded as civic duty, whereby both owner and visitor benefit by taking part in the general enhancement of the nation’s cultural well-being.”[26]

In 1828, together with his friend, the architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781–1841), Waagen wrote a memorandum commissioned by Wilhelm von Humboldt on the projected organization and presentation of the Neues Museum in Berlin. Concrete proposals on lighting, disposition, and hanging were formulated to enhance the didactic power of the works of art, following the role assigned to the museum as educator of the people.[27] A “pioneer scholar-curator who appreciated the importance of clarity, order and interpretation,”[28] Waagen similarly assessed all the artworks he saw in England with the eye of a museum director, taking into account their immediate environment and transposing the criteria he applied to curating museums and public galleries to private spaces. He often expressed his frustration at seeing artworks treated as mere ornament, particularly when their positioning on the wall prevented a scholarly, detailed observation.[29] Although his remark that “The light yellow paper on the walls [of the Earl of Grey’s drawing room] is . . . very unfavourable to the effect of the pictures” may sound trivial,[30] such comments illustrate contemporary debates in Germany on the aesthetics of perception and on theories of color and light that had real consequences for museum practice.[31]

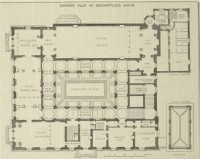

Since Waagen’s first visit to England in the mid-1830s, many private collectors had either transformed a room into a gallery or had a gallery built to create the appropriate setting for their artworks. This was the case for the collection in Bridgewater House, designed by Charles Barry (1795–1860), “with express reference to its suitable accommodation” (fig. 1).[32] When The Builder reported on the planned alterations in 1849, it mentions as the chief motive “a desire to render the gallery and its approaches independent of the rest of the building,” in order “to afford the greatest possible facilities to the public for visiting this fine collection.”[33] While Waagen also acknowledges Bridgewater’s as “first rank among all the collections of paintings in England,” his judgement of the display and architecture is critical, because, in his opinion, they failed to meet the standards expected of the setting for such valuable artworks: “Unfortunately the lighting of the chief gallery is so unsuccessful that the enjoyment of these treasures of art is greatly impeded.”[34] Neither was Waagen convinced by the Italianate architecture of the hall, comparing it with other designs by Barry and similarly unfavorably with the architecture of another private palace: “Altogether this celebrated architect appears less happy in the Italian than in the Gothic style, and there is no doubt that this building, in the taste of the forms and decorations, is inferior to its stately neighbour, Stafford House.”[35] The latter, on the contrary, had been adorned since 1835 with “a fine gallery, admirably lighted, partly from above and partly from the narrow ends . . . , in which the chief of the best pictures are worthily placed.”[36]

As a museum director, Waagen dedicated a significant part of his commentaries to another crucial task, the conservation of artworks. In this respect, he judged that the Duke of Devonshire was setting a bad example, made all the worse by the “extraordinary value” of his artworks: “Many of the pictures in this rich collection are seen to disadvantage from having become dry and dirty. The Duke has, however, such an aversion to picture-cleaners that he cannot make up his mind to remedy this evil. . . . On the other hand, however, the increasing dryness of the paint gives reason to fear its falling off in scales, and, consequently, the total ruin of several of them.”[37] Hinting at the low quality of the work of some picture-cleaners to explain the Duke’s reluctance, Waagen claimed that “most of the pictures in the world [were] placed in a similar position between Scylla and Charybdis.”[38] Implicitly, this claim confirms that curators needed to be professionally trained, a training that would be best organized within the context of the public museum. Putting museum professionals in charge of the conservation of the art of the nation would solve the dilemma experienced by private collectors of having to choose between deterioration and careless restoration.

Nevertheless, Waagen admitted that private patronage was sometimes essential in gaining new treasures for the nation, as in the case of the Hertford collection, which had been “one of the chief inducements”[39] for his second journey to England. This series of masterpieces from the greatest painters of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries had been purchased “at prices seldom given by Governments, still less by private individuals.”[40] It was even more regrettable that such pains should have been taken by Francis Seymour-Conway, 3rd Marquess of Hertford (1777–1842), to acquire these artworks as, with the exception of a few items, the collection “was lying, well packed, in the Pantechnicon” during Waagen’s stay in London, while Manchester House was being rearranged to accommodate it.[41] The growing sense of responsibility among private collectors over this period is illustrated by the fact that this would later become the Wallace Collection, bequeathed to the nation in 1897, along with the house it was held in.

Waagen was adamant that this situation was unacceptable on two counts, the main reason being, once again, the conservation of the objects: “Old pictures require perpetual vigilance so as to counteract or prevent any mischief, such as chilling of the varnish, or flaking off of the colour, etc. It is much to be feared that, after having remained packed for many years, excluded from light and air, they will be found on opening the cases in a more or less injured condition.”[42] To the museum man, such casualness amounted to an act of professional negligence. Treasures of Art thus reveals the ambivalence of art ownership, with collectors being in charge of artworks on behalf of a collective.

Moreover, limiting access to the Hertford collection was a failure to fulfil the second major requirement of a collector: that of exhibition. As a counterpoint to the Marquess of Hertford, Robert Stayner Holford (1808–92) was a model of “how much may be done where great wealth is combined with excellent powers of judgement.”[43] Holford’s collection was kept in a rented house in Russell Square (which had formerly been occupied by Thomas Lawrence) during the construction of more suitable premises: a mansion in Park Lane, Dorchester House, to which Holford went on to afford admission “with the greatest liberality to all lovers of art desirous of seeing his pictures.”[44] The great contrast from one private collection to another was challenged by Anna Jameson:

Without entering into the question how far a man has or has not a right to do what he likes with his own, if it be true that we shall be held responsible for the use or abuse of every good gift entrusted to us, what can be said of the possessor of a magnificent gallery, who shuts it up from all participation, but that he is the worst of misers? The wretch who hoards his gold is bad enough, but what shall be said of him who shuts up fountains of thought and enjoyment from the thirsty heart fainting on the dry dusty path of common life?[45]

In drawing a connection between spiritual improvement and contact with beauty, Jameson expressed Victorian values that were in line with the German scholarly ideal of the Enlightenment. While she appealed to the moral duty of the wealthy individual as a philanthropist, Waagen expanded this sense of responsibility to include the necessity for education and advancement of knowledge, the third part of a curator’s work.

Henry Thomas Hope (1808–62) embodied this spirit of discovery. His house contained a collection assembled by his father, Thomas Hope, who produced a series of designs published in Household Furniture and Interior Decoration in 1807.[46] Waagen deemed the family’s house on Duchess Street “a real museum of art.”[47] He particularly admired the Dutch and Flemish cabinet pictures (fig. 2): “This collection is distinguished from all others of the kind in England by containing, besides pictures of those masters who are in vogue here, a number of others less known, and, in some respects, of great merit, so that an opportunity is afforded of acquiring a very correct knowledge of this school.”[48] This assessment echoed a vital concept in public galleries and museums: a collection and an exhibition should form a didactic framework, establish connections, and contextualize in order to give a sense of the history of art.

In Waagen’s opinion, this role was fully achieved by the collection of Algernon Percy, 4th Duke of Northumberland (1792–1865). It contained copies of Raphael’s School of Athens by Anton Mengs (“undoubtedly the best copy ever made of this celebrated picture”), of Raphael’s frescoes for the Villa Farnesina, of Annibale Carracci’s Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne, and of Guido Reni’s Apollo in the Chariot of the Sun, all displayed with as much care as if they were authentic: “In the gallery, a magnificent and splendidly decorated apartment, of considerable height and length, hang copies of well-known works, of the same size as the originals.”[49] In spite of their inauthenticity, the general effect of these reproductions on the spectator was no less “grand and pleasing,” according to Waagen. On the contrary, he regarded this form of patronage very highly: “The idea of making this admirable selection of the most celebrated works, and having them copied by able artists, affords me a new proof that the English nobility possess not only money, but knowledge and taste to employ it in the most worthy manner.”[50] The making of copies helped to promote artistic education through imitation of the old masters, and enabled the owners to enjoy a daily contact with canonical artworks.

Some collectors were thus distinguished in Treasures of Art by their ability to act truly as scholars and to develop a keen sense of art historical matters. Waagen found in Lord Lansdowne (1816–66), for example, “that union of refinement with simplicity and natural benevolence which is so winning in persons of rank,” but also “an elevated and cultivated taste, and such general knowledge of the subject, as is seldom met with in England or elsewhere.” The 4th Marquess of Lansdowne’s greatest merit was his “equally warm interest in the art of sculpture, and in the different developments of painting in the earlier forms, of which he duly appreciated the profound intellectual value.”[51] The main sculptures had been collected by Lord Shelburne, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne (1737–1805), between 1765 and 1773, and had occupied specially fitted niches and exhibition spaces in the house, which had originally been designed by Robert Adam (1728–92) in the early 1760s.[52]

In 1851, the impact of the architecture on the visitor was still striking: “Immediately on entering the hall you perceive that the more elevated worship of art is not wanting; for, antique statues, bas-reliefs, and busts crowd upon the eye and make a very picturesque effect.”[53] The description of the house in Treasures of Art reconstitutes the spatial composition of its interiors, the harmony of which is a credit to the collector’s curatorial talents:

The two ends of the apartment are formed by two large apse-like recesses, which are loftier than the centre of the apartment. In these large spaces antique marble statues, some of them larger than life, are placed at proper distances with a crimson drapery behind them, from which they are most brilliantly relieved in the evening by a very bright gaslight. This light, too, was so disposed that neither the glare nor the heat was troublesome. The antique sculptures of smaller size are suitably disposed on the chimney-piece and along the walls.[54]

The aesthetic effect of the presence of artworks within the home finds its climax in descriptions that present these houses as works of art in their own right, belonging to the ensemble formed by the art of the nation. The great hall and staircase in Stafford House, in particular (fig. 3), is worthy of being described in terms otherwise used for the masterpieces of painting that Waagen catalogued: “The fine proportions, the colour of the walls, which are an admirable imitation of Giallo antico, and the rich balustrades of gilt bronze, have a surprising and splendid effect.”[55] Into this pictorial setting, Waagen places his memory of a ball that he attended in 1835:

The distinguished company, attired in the richest dresses, were seen dispersed in the hall, on the noble staircase, and in the gallery above; thus this grand architecture was furnished with figures corresponding with it, and the figures with a suitable background. This magnificent scene, brilliantly illuminated, afforded such a beautiful and picturesque sight, that I fancied myself at one of those splendid festivals which Paul Veronese has represented in his larger pictures with such animation and incomparable skill.[56]

Thus, a symbiosis between art lovers and the artworks that formed their daily environment emerges within the most ambitious private collections.

Private House and Public Persona

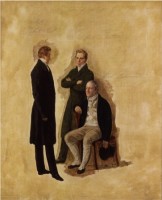

Waagen applied the technical criteria of a public display to private space, enhancing the dynamics between the private ownership of artworks and the public aura that it created. For instance, in the case of Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel (1788–1850), Waagen considered that the well-conceived arrangement of Peel’s collection at 4 Whitehall Gardens (fig. 4) revealed him “not as someone who considered works of art, as is too often the case, as mere expensive ornaments for a drawing-room, but rather desired to enjoy each, as a true friend of the arts.”[57] Peel was a keen connoisseur, able to explain the “particular excellence” of each item of his collection of Flemish and Dutch paintings.[58] This artistic taste was encouraged in all members of the household: “The apartment which contains all these treasures is one of those which Sir Robert Peel constantly occupied, so that he and his family made themselves thoroughly acquainted with these masterpieces.”[59] At the same time, being “a true friend of the art” enhanced Peel’s public and political prestige. This was symbolized by the location of Whitehall Gardens: “Though very near the House of Commons, the theatre of his public life, it has all the advantages of almost rural retirement and tranquillity, with a fine view over the Thames.”[60] The concept of the painting Patrons and Lovers of Art, by Pieter Wonder, which represents George Wyndham, 3rd Earl of Egremont, and Robert Peel alongside the painter David Wilkie (1785–1841) in a study dating from around 1830 (fig. 5), shows that posing as a lover of art, and thus disclosing a private passion, was also beneficial to public life.

The following description of Panshanger, the country estate of the Cowper family in Hertfordshire, exposes an unexpected ambivalence in Waagen’s views on universal access to art. In fact, the way the circumstances of his visit are presented seems to assert his privilege:

After walking through a part of the fine park, I reached the mansion, and being provided, by the kind intervention of the Duke of Sutherland, with a letter from Lady Cowper to the housekeeper, all the rooms containing pictures were opened to me, and I was then left to myself. The coolness of these fine apartments, in which the pictures are arranged with much taste, was very refreshing after my hot walk. The drawing-room, especially, is one of those apartments which not only give great pleasure by their size and elegance, but also afford the most elevated gratification to the mind by works of art of the noblest kind.[61]

In the confines of the silent, protected space of the country estate, an idyllic aesthetic experience could take place:

I cannot refrain from again praising the refined taste of the English for thus adorning the rooms they daily occupy, by which means they enjoy, from their youth upward, the silent and slow but sure influence of works of art. I passed here six happy hours in quiet solitude. The silence was interrupted only by the humming of innumerable bees round the flowers which grew in the greatest luxuriance beneath the windows.[62]

Waagen’s remark that “it is only when thus left alone that such works of art gradually unfold all their peculiar beauties” reveals a jarring discrepancy between his official, public positions and his true personal views. This explains why the return to reality was so abrupt: “When, as I have too often experienced in England, an impatient housekeeper is perpetually sounding the note of departure by the rattle of her keys, no work of art can be viewed with that tranquillity of mind which alone ensures its thorough appreciation.”[63]

Although Treasures of Art permitted the reader to enter an otherwise prohibited space, thus enabling access to these well-kept treasures, at least on paper, the seclusion of the artworks was paradoxically presented as a necessary condition for their enjoyment. One could draw a comparison with Victorian values, as represented by Anna Jameson’s disapproval of the visitors whom she judged unworthy of seeing the artworks on display at open days at Bridgewater House: “The loiterers and loungers, the vulgar starers, the gaping idlers, . . . people, who, instead of moving amid these wonders and beauties, ‘all silent and divine,’ with reverence and gratitude, strutted about as if they had the right to be there; talking, flirting, peeping, and prying; . . . touching the ornaments—and even the pictures!”[64] There is an inherent conflict between the pedagogical aspirations of a museum director, whose task it is to compose the best possible setting for collective enjoyment of the art, and what Waagen presented as a British ideal of solitary appreciation in a protected, privileged environment. Therefore, it appears that Jameson’s call for private collectors to share their wealth of artworks with the world was intended to be limited to those who were educated enough to prove themselves worthy of seeing them. She finds it natural that some estates should be reluctant to open their doors to the public: “Can we wonder that men of taste—Englishmen, who attach a feeling of sanctity to their homes—should hate the idea of being subjected to vulgar intrusion, merely because they have a Raphael or a Rubens of celebrity?”[65] Waagen, too, acknowledges that granting access to private collections was an act of “generosity” on the part of “noble proprietor[s].”[66]

A New Generation of Art Lovers

Alongside the traditional portrait of an aristocracy keen to be seen in public as protectors of art, while still preserving the privilege of enjoying their artworks as integral elements of their private homes, Waagen also “gave due prominence to the new middle-class collector-patrons like Sheepshanks and Vernon, whose emergence was a phenomenon of early Victorian times.”[67] The diversification of art collectors’ social origins to include the middle class is an indicator of the cultural transformation that followed in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, as noted by Elizabeth Eastlake around the time of Waagen’s travels: “The patronage which had been almost exclusively the privilege of the nobility and higher gentry, was now shared . . . by a wealthy and intelligent class, chiefly enriched by commerce and trade.” This, Eastlake writes, went hand-in-hand with a shift in the nature of the collections themselves, where English paintings began to dominate over old masters: “collections, entirely of modern and sometimes only of living artists, began to be formed. For one sign of the good sense of the nouveau riche consisted in a consciousness of his ignorance upon matters of connoisseurship. This led him to seek an article fresh from the painter’s loom, in preference to any hazardous attempts at the discrimination of older fabrics.”[68]

Dianne Sachko Macleod has shown that this is a skewed perspective on middle-class patrons, insofar as they were in the majority several generations after the moment when their family was indeed parvenu and had therefore had time to create an understanding of art that distinguished itself from the patrician model.[69] Similarly, Waagen presents middle-class collectors in a more positive light than Eastlake, praising their equal interest for contemporary painters and for old masters alike, as in the case of Thomas Hope’s Dutch and Flemish cabinet pictures, as stated see above. The treatment of private collections in middle-class homes seems to have been no different from the treatment of those of the gentry, as exemplified by Waagen’s entry on Elhanan Bicknell (1788–1861), merchant and shipowner:

I was indebted to my friend David Roberts, the painter, for an introduction to Mr. Bicknell, who resides at a pleasant country seat a mile from Dulwich. This gentleman, who has made a large fortune, chiefly in the whale fishery, is so zealous a lover of art as to have literally filled his house with pictures, including a series of masterworks by the most eminent English artists. In the absence of Mr. Bicknell the elder, I was accompanied in my inspection of the collection by his son, who has inherited all the love of art which distinguishes the father.[70]

Here, the notion of inheritance is associated with the intangible benefit of increased cultural standing. The transmission of aesthetic appreciation as a value through the generations, as alluded to by this passage from Treasures of Art, seems to confirm Macleod’s analysis, according to which the common denominator in the diverse group of Victorian collectors from the middle class was “the realisation that a life dedicated to money and worldly success was incomplete without the presence of art in the home.”[71]

A particularly telling example is Leeds merchant John Sheepshanks (1787–1863), who moved to London in 1827.[72] Sheepshanks belonged to a family of wealthy manufacturers. He sold his collection of Flemish and Dutch etchings to the British Museum in 1836 and used the profit to create a gallery of English paintings in his house. Not only was he housing the art of the nation, but he also dedicated his private space to the promotion of national art. In 1851, his English gallery contained 226 objects, the majority of which were by contemporary painters such as Charles Leslie (1839–86) or Edwin Landseer (1802–73). Waagen also included the Irish painter William Mulready (1786–1863) in this category in his listing. Thus, Sheepshanks was “animated by a true love of art,” but also by a “kind interest in the artist.”[73] For middle-class collectors, curating and patronage were part of the same project of building “the social order they sought to harness” through symbolic means.[74]

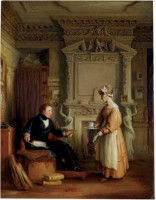

The representation of the Victorian collector necessitated a new form of relationship with the artist, as well as the elaboration of new visual codes. In Mulready’s portrait of Sheepshanks (1832–34; fig. 6), described by Waagen as being “of great truth in every portion,”[75] the collector is seen leafing through a book of engravings (hinting at the range of possibilities created by the development of mechanical reproduction) in a domestic scene: “Mr. Sheepshanks [is] seated by the fireplace, giving an order to a maid-servant.”[76] This intimate atmosphere is also reflected in the title by which the painting came to be known, John Sheepshanks at His Residence. This low-key, though elegant environment was intended to set the tone for a new way of appreciating art within the home. Moreover, the presence of this portrait of Sheepshanks in his own collection created a symbolic mise en abyme for the new generation entering the collecting world.

Conclusion

After Robert Vernon (1774–1849) set an example by donating his collection of modern art to the nation in 1847, Sheepshanks made a deed of gift in 1857, in which he demanded that “the public, and especially the working classes, shall have the advantage of seeing the collection on Sunday afternoon.”[77] As a private collector, Sheepshanks had acknowledged that his collection had become part of the national artistic heritage, for which he, as curator, was responsible. Throughout Treasures of Art, collections held in private homes are presented as “an extension of the owner’s identity, which, in the case of the Victorians, extended beyond the personal to a sense of cohesion with their class.”[78] This statement also holds true for the spatial display and the architecture. Waagen’s catalogues record the budding awareness of a national artistic heritage in Britain through the involvement of private collectors in the acquisition and production of artworks with which their name would remain securely associated. While affirming the collector’s ownership of the art of the nation, Treasures of Art captures the turning point at which these private patrons acknowledged and embraced a public responsibility to curate the art present in their homes, in line with the new paradigm of the “exhibition age.”

[1] This article is based on a paper entitled “Housing the Art of the Nation: The Home as Museum in Gustav F. Waagen’s Treasures of Art in Great Britain” (presentation, Historians of British Arts panel, “Home Subjects: The Display of Art in the Private Interior 1753–1900,” College Art Association Annual Conference, New York, February 12, 2015).

[2] James Hamilton, A Strange Business: Making Art and Money in Nineteenth-Century Britain (London: Atlantic, 2014), 255.

[3] Gustav Friedrich Waagen, Treasures of Art in Great Britain, 2 vols. (London: Murray, 1854–57), 1:37.

[4] John Trumbull, Catalogue of a Most Superb and Distinguished Collection of Italian, French, Flemish, and Dutch Pictures, a Selection Formed with Peculiar Taste and Judgement by John Trumbull, Esq. during his Late Residence in Paris, from Some of the Most Celebrated Cabinets in France (London: Christie, 1797), iii.

[5] Waagen, Treasures of Art, 1:37.

[6] See Francis Haskell, The British as Collectors in the Treasure Houses of Great Britain (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1985).

[7] See Suzanne Fagence Cooper, “The Art Treasures Exhibition, Manchester, 1857,” Magazine Antiques 159 (June 2001): 926–33.

[8] See Charlotte Klonk, “Mounting Vision: Charles Eastlake and the National Gallery of London,” The Art Bulletin 82, no. 2 (June 2000): 331–47; Susanna Avery-Quash and Julie Sheldon, Art for the Nation: The Eastlakes and the Victorian Art World (London: National Gallery Company, 2011).

[9] See Émilie Oléron Evans, “Gustav Friedrich Waagen et l’institutionnalisation des ‘trésors de l’art’ en Grande-Bretagne,” Revue germanique internationale 21 (2015): 51–64.

[10] Giles Waterfield and Florian Illies, “Waagen in England,” Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 37 (1995): 47–59; Francis Haskell, The Ephemeral Museum: Old Master Paintings and the Rise of the Art Exhibition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000); Elizabeth Pergam, The Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition of 1857: Entrepreneurs, Connoisseurs and the Public (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011).

[11] Giles Waterfield, “The Town House as Gallery of Art,” The London Journal 20, no. 1 (May 1995): 47–66; Carmen Stonge, “Making Private Collections Public: Gustav Friedrich Waagen and the Royal Museum in Berlin,” Journal of the History of Collections 10 (1998): 61–74.

[12] See William Buchanan, Memoirs of Painting with a Chronological History of the Importation of Pictures by the Great Masters into England Since the French Revolution, 2 vols. (London: Ackerman, 1824), 1:xiv–xv; Jordana Pomeroy, “The Orléans Collection: Its Impact on the British Art World,” Apollo 145, no. 420 (February 1997): 26–31; Francis Haskell, Rediscoveries in Art: Some Aspects of Taste, Fashion and Collecting in England and France (London: Phaidon Press, 1976), 24–37; Robert Panzanelli and Monica Preti-Hamard, eds., The Circulation of Works of Art in the Revolutionary Era, 1789–1848, part 1: The Orléans Effect (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2007), 25–83.

[13] Buchanan, Memoirs of Painting, 1:vi.

[14] Waagen, Treasures of Art, 1:35.

[15] Johann David Passavant, Tour of a German Artist in England: With Notices of Private Galleries and Remarks on the State of Art (London: Saunders and Otley, 1836); Anna Jameson, Companion to the Most Celebrated Private Galleries of Art in London: Containing Accurate Catalogues, Arranged Alphabetically, for Immediate Reference, Each Preceded by an Historical and Critical Introduction, with a Prefatory Essay on Art, Artists, Collectors, and Connoisseurs (London: Saunders and Otley, 1844).

[16] Wilhelm Waetzoldt, Deutsche Kunsthistoriker, vol. 2, Von Passavant bis Justi (Berlin: Hessling, 1965), 15.

[17] Jameson, Companion, 383.

[18] See for example Waagen, Treasures of Art, 1:188.

[19] See Haskell, The Ephemeral Museum, 47.

[20] Peter Humfrey, “The Stafford Gallery at Cleveland House and the 2nd Marquess of Stafford as a Collector,” Journal of the History of Collections (2014), doi:10.1093/jhc/fhu065.

[21] Humfrey, “The Stafford Gallery.”

[22] Inge Reist, “The Fate of the Palais Royal Collection 1791–1800,” in Panzanelli/Preti-Hamard, eds., Circulation of Works of Art in the Revolutionary Era, 22–44, 37.

[23] Passavant, Tour of a German Artist in England, 59.

[24] Waagen, Treasures of Art, 2:88.

[25] Ibid., 1:396.

[26] Reist, “Fate of the Palais Royal Collection,” 37.

[27] See Friedrich Stock, “Zur Vorgeschichte der Berliner Museen. Urkunden von 1786–1807,” Jahrbuch der Preussischen Kunstsammlungen 51 (1930): 205–22.

[28] Hamilton, A Strange Business, 285.

[29] See for example Waagen, Treasures of Art: “It hangs too high to form a decided opinion” (2:60) and “the picture hangs too high for proper appreciation” (2:182).

[30] Waagen, Treasures of Art, 2:85.

[31] See Johann von Goethe, Zur Farbenlehre (Tübingen: Cotta, 1810), translated into English by Charles Eastlake, Theory of Colours (London: Murray, 1840).

[32] Waagen, Treasures of Art, 2:25.

[33] “The Altered Plan of Bridgewater House, London,” The Builder, October 13, 1849, 484.

[34] Waagen, Treasures of Art, 2:25.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid., 2:59.

[37] Ibid., 2:88.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid., 2:154.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid., 2:193.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Jameson, Companion, 79.

[46] Thomas Hope, Household Furniture and Interior Decoration, Executed from Designs by Thomas Hope (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, & Orme, 1807).

[47] Waagen, Treasures of Art, 2:112.

[48] Ibid., 2:115.

[49] Ibid., 2:394.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid., 2:143.

[52] See James Parker, “Patrons of Robert Adam at the Metropolitan Museum,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 1 (1968): 109–124.

[53] Waagen, Treasures of Art, 2:143.

[54] Ibid., 2:144.

[55] Ibid., 2:58.

[56] Ibid., 2:58–9.

[57] Waagen, Treasures of Art, 1:397.

[58] See J. Mordaunt Crook, “Sir Robert Peel: Patron of the Arts,” History Today 16, no. 1 (January 1966): 3–11; Richard E. Gaunt, Sir Robert Peel: The Life and Legacy (London: Tauris, 2010).

[59] Waagen, Treasures of Art, 1:413.

[60] Ibid., 1:397.

[61] Ibid., 3:7.

[62] Ibid., 3:7–8.

[63] Ibid., 3:8.

[64] Jameson, Companion, xxxiv–v.

[65] Ibid., xxxv.

[66] Waagen, Treasures of Art, 2:55.

[67] Susan M. Pearce, “Introduction,” in Gustav Friedrich Waagen, Treasures of Art in Great Britain, repr. from the 1854 edition, ed. Susan M. Pearce (London: Conmarket, 1970).

[68] Lady Eastlake, “Memoir,” in: Sir Charles Locke Eastlake, Contributions to the Literature of the Fine Arts with a Memoir Compiled by Lady Eastlake, 2nd ed. (London: 1870), 147.

[69] See Dianne Sachko Macleod, Art and the Victorian Middle Class: Money and the Making of Cultural Identity (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 4.

[70] Waagen, Treasures of Art, 2:349.

[71] Macleod, Art and the Victorian Middle Class, 30.

[72] See Martin Royalton-Kisch, “An Archive of Letters to John Sheepshanks,” The Volume of the Walpole Society 66 (2004): 231–254.

[73] Waagen, Treasures of Art, 2:299.

[74] Macleod, Art and the Victorian Middle Class, 30.

[75] Waagen, Treasures of Art, 2:304.

[76] Ibid., 2:304.

[77] John Sheepshanks, “Deed of Gift,” February 6, 1857, Minute Book of the Department of Science and Art, Victoria and Albert Museum Library, London, 3–4.

[78] Macleod, Art and the Victorian Middle Class, 10.