The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

The EY Exhibition: Impressionists in London, French Artists in Exile (1870–1904)

Tate Britain, London

November 2, 2017–May 7, 2018

Catalogue:

The EY Exhibition: Impressionists in London, French Artists in Exile (1870–1904).

Caroline Corbeau-Parsons.

London: Tate Publishing, 2018.

272 pp.; 200 color illus.

$55.00 (hard cover)

ISBN: 1849765243

If the 1874 inaugural exhibition of the Société anonyme des peintres, sculpteurs et graveurs marks a climatic date in the history of Impressionism, then 1973 marks an equally climatic one in the historiography and museography of nineteenth-century art. That year, John Rewald’s History of Impressionism would appear in its third and final imprint; T.J. Clark’s Absolute Bourgeois: Artists and Politics in France, 1848–1851 and its companion tome, Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution, would be printed for the first time; and while to less fanfare, The Impressionists in London exhibition would be mounted at the Hayward Gallery.[1] Scrutinizing the circulation of the French Impressionists outside France, The Impressionists in London adopted a tack now readily taken by adherents to transnationalism and proponents of global modernism. Presciently appreciating the promise of that approach, John House, in a review for The Burlington Magazine, nonetheless took curators Alan Bowness and Anthea Callen to task for the “misleading” title that had sweepingly reduced the artists on exhibit to the “Impressionists” and the places depicted by them to “London.”[2] Initially cautioning that André Derain’s serialized, Fauvist, tourist treatment of the river Thames did not warrant a place beside the truly Impressionist paintings by Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, House felicitously demurred that “the Derains . . . are a great gain to the show . . . broaden[ing] its scope without diluting its effect.”[3]

Rather than fire a similar fusillade at the eponymous Tate Britain exhibition The EY Exhibition: The Impressionists in London, French Artists in Exile (1870–1904), current curator Caroline Corbeau-Parsons has learned some salient lessons from the Hayward Gallery. She has corrected a key complaint: Tate Britain glistened and gleamed with depictions of London, its environs, and its inhabitants. Except for the introductory room replete with paintings, prints, photographs, and sketchbooks documenting the destruction wrought by the Franco-Prussian War and Commune, and so laying the groundwork for what followed, the current Impressionists in London concentrated on London. But to the point that its 1973 precedent surveyed art and artists far afield from the Impressionists, Corbeau-Parsons has not entirely corrected the conceit: the Impressionists Monet, Pissarro, and Sisley were to be seen here, but so too were artists not thusly classified. Painted fripperies by James (Jacques-Joseph) Tissot, sculptures of sweetly maternal affection by Jules Dalou, and serious marble busts by Antoine Carpeaux, engraved and etched work by Alphonse Legros, and once more, Fauvist scenes of the Thames by Derain remain beyond the bounds of present-day definitions of Impressionism (fig. 1). Though the subtitle presumably has been added to sharpen the scope, the designation of these artists as all exiles (“French Artists in Exile”) has complicated their legal status much as Impressionism complicated their stylistic classification: not all these artists were Impressionists (whether we accept Impressionism as an applicable label before the 1874 Société anonyme would seem to be an unanswered but pertinent question); not all these artists were French citoyens (citizens); not all the artists who were French identified as such; and not all the Impressionists or non-Impressionists were always or ever exiles (not Derain).

It may seem that, like the legendary morning fogs and mists rolling off the river Thames, the very premise of the exhibition dissolved due to lexical, political, and art historical complications around these two terms: Impressionism and exile. However, this same murkiness paradoxically proved critical to understanding the exhibition’s aims and appreciating its accomplishments. Predicated on the historical incertitude of the war and its fallout, and on the artists’ constantly shifting experiences and responses to that uncertainty, The Impressionists in London marshaled a diverse set of artists to tell a subtle and sophisticated tale—one that stubbornly refused to collapse into a simplified story of Impressionism, and so complicated the nineteenth-century history and twentieth-century historiography of that art. While what was exhibited transgressed Impressionism and exile, Corbeau-Parsons and the curatorial team’s achievement supersedes the limits imposed by terms and titles. Corbeau-Parsons has curated not one story of the Franco-Prussian War and its fallout, but multiple stories that richly overlap, compete, and contradict, and thereby test viewers’ ability to remember the grittiness of wartime realities behind these beautifully painted surfaces (fig. 2). Some of the exhibition’s narrative instabilities may be categorized as historical, for instance the lurching transitions from military cataclysm and civil catastrophe to disruptions of daily life, and the subsequent decades of recovery, restoration, and eventually, a return to normalcy. Some of its instabilities may be classified as curatorial, for instance the inclusion of an eclectic assembly of artists who each occupied a specific habitus (political sympathies, economic status and social networks) and so experienced and portrayed London from shared but also and ultimately disparate positions. Though united by their decision to relocate to London—pockets of artists from France were found in “Soho, from Convent Garden to Oxford Street” and Kensington—each artist plied his (no women artists were included) paintbrush, chisel, or burin to specific ends and effects (60). And some of the exhibition’s instabilities may be considered etymological, historiographical, and perceptual, for instance the constantly evolving definition and conception of “Impressionism” as a critical term that circulated in and between nineteenth-century England and France.

To be precise: this was not an exhibition on Impressionism’s supposed origins in England or its indebtedness to English landscape traditions perpetuated by the Constable-Turner-Bonington trifecta.[4] Nor was it an exhibition limited to the eight or nine artists now known as the Impressionists and their early entry into London’s art market.[5] Nor was it dedicated to Impressionist depictions of London’s hazily shrouded skyline and its fog-cloaked, smog-choked streets (though such scenes abounded, especially in the penultimate room dedicated to Monet’s Houses of Parliament series) (fig. 3). Instead, across nine rooms packed with assorted media (paintings, prints, marble and terracotta sculptures, medals, photographs, and artist sketchbooks), The Impressionists in London tracked these artists as they crossed the Channel in the midst or immediate aftermath of the war and Commune. (Whether these artists typified the experiences of their fellow Frenchmen—thousands, some of them ex-Communards and so political refugees, sought safety and security on English shores—remains an unanswered but once more pertinent question.) These artists fled conscription (Monet), escaped destroyed homes (Pissarro), pursued professional opportunities and markets (Dalou and Tissot), or followed their beleaguered patrons abroad (Carpeaux). Upon their return to France—at different moments due to different reasons and to different extents (not all repatriated immediately after the end of the Commune; some lived out their lives in London; some eventually returned to Paris not for political but for personal reasons)—the exhibition traced these artists’ intermittent travels back to London in the 1890s and 1900s and concluded with those following in their footsteps and brushstrokes.

London was a critical site for the early exhibition and criticism of Impressionism. Even before art-critical allies Philippe Burty and Stéphane Mallarmé had their articles on the Société anonyme des peintres, sculpteurs et graveurs translated and circulated in the city’s news outlets, correspondents for The Times and Art Journal broadcast their reactions to Impressionism—not always complimentary.[6] An anonymous review in The Times launched a salvo of criticism against a Bond Street show of French and Foreign Painters:

There is less than the usual proportion of protest-provoking pictures—a not unfair description for a good deal of the work of the young French painters, who seem to have surrendered themselves without reserve to a hankering after ugliness in their figure painting, and a studio avoidance of selection and arrangement in their landscape. This school, which, we presume, claims to be naïve, but which we should call coarse and ostentatiously defiant both of rule and culture, still make ‘act of presence’ here quite conspicuously enough in the obtrusively ugly group.[7]

Despite taking flak, the Impressionists continued to pursue opportunities to exhibit in London-based galleries throughout the next two decades.

Coupled with local broadsides, translated histories of Impressionism authored by French critics also flowed across the Channel. In 1903, The French Impressionists by Camille Mauclair appeared in British bookstores and libraries; in 1910, Manet and the French Impressionists by Théodore Duret appeared on those same shelves.[8] Rather than intellectual accord, this plethora of art-critical and art historical literature resulted in etymological and epistemological contradictions around which artists, artworks and painterly styles qualified as “Impressionist.” “By the turn of the century,” as Kate Flint has underlined, “[in England] the word ‘Impressionism’ was being used so widely, so loosely, that it was tending to forfeit its original meaning.”[9] A fine but firm line separates the dissolution of original meanings and meaninglessness. Mapping the global modern demands an attention to how “Impressionism” as a term, concept, style and set of artistic practices crisscrossed geopolitical, linguistic and cultural boundaries. As conceptually and rhetorically “Impressionism” expanded to “mean a variety of things by a variety of people”—its use swelled to include Tissot and Whistler alongside the standard Monet and Pissarro—it accrued not less but more lexical, cultural, art-critical, and art historical significance.[10] In extending Impressionism beyond the eight or nine artists to whom this epithet has tended to be applied, The Impressionists in London may have spurred art historians to question the history and historiography of this art: what discrepancies, the exhibit implicitly asked, mark past and present applications of Impressionism? As a critical term for art history, how was “Impressionism” defined, translated, and circulated between France and Britain? How did these ideas of Impressionism metamorphose from 1870 to 1904?

If one accepts The Impressionists in London as asking such questions, it follows that the exhibition could be seen as successfully underscoring differences between the exclusivity of Impressionism and comparative inclusivity of the Société anonyme. The 1870s independent exhibitions of Société anonyme—now so closely identified with the Impressionists—encompassed a wide array of artists now classified as Naturalist or Realist (Legros, Giuseppe de Nittis, and Tissot); in early-1870s London, many of these same Naturalists and Realists had extended their London-based circles to include the Impressionists. Like the Société anonyme that exhibited the Italian-born de Nittis and English-transplant Legros (Tissot and Whistler declined to participate), Tate Britain similarly displayed these artists and so highlighted the social as much as the artistic connections between them.[11] Opening his home to French friends and fellow artists fleeing the military and political troubles abroad, for example, Legros connected them to opportunities, exhibitions, and people (fig. 4). To further connect the more marginal or peripheral participants in the Société anonyme and core Impressionists, The Impressionists in London would have benefitted from the addition of prints by Legros and paintings by de Nittis displayed at those exhibitions.

In deploying all these artists across the stylistic battle lines, Corbeau-Parsons has seemingly emulated the approach to the Franco-Prussian War and Commune taken by Hollis Clayson, whose Paris in Despair carefully plotted a constellation of artists’ wartime experiences from their shared locus in Paris.[12] Like Clayson, Corbeau-Parsons has explained the war and the subsequent civil strife as cataclysms since faded from memory and replaced by the horrors of the two World Wars.[13] Clayson has effectively detailed how Paris the city and its population suffered mightily and miserably in the Terrible Year (1870–71). Waves of refugees washed ashore in Britain: first came those escaping the foreign onslaught on Paris and starvation of its population; then came those absconding the bloodiness of the Commune; and finally came those avoiding imprisonment as ex-Communards. Despite our current distance from these traumas, memories of the war and the Commune smoldered for decades, set ablaze by the constant sight of the ruined Palais de Tuileries and Hôtel de Ville. Paintings, sculptures, and etchings shown at the Salon as early as 1872 depicted the capital’s brutal destruction. In place of Ernest Meissonier’s Ruines des Tuileries so often used to illustrate these ruins, Corbeau-Parsons selected paintings by Camille Corot and Siebe Johannes ten-Cate, juxtaposing them with Carpeaux’s sketchbook flipped to a pencil drawing of a pile of corpses, casualties of the recent violence. Compared with these inescapably graphic horrors of war, Ten-Cate’s The Carousel and the Tuileries Palace After the Fire of 1871 pushes the ruins to the physical and psychological backdrop. Presented as an ordinary street scene on a rainy day, none of Ten-Cate’s painted passersby mind the nearby ruins. Omnibuses, uniformed gendarmes, top-hatted bourgeoisie, pedestrians huddled under umbrellas and peasants in regional dress bustle on their way, strolling quickly past this site and so striding quickly away from the recent historical past (fig. 5).

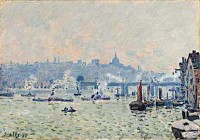

On the opposite side of this introductory wall lined with gloomy photographs depicting the decimated capital, the exhibition’s first room was filled with paintings by the Impressionists, including The Thames below Westminster by Monet and View of the Thames: Charing Cross Bridge by Sisley (figs. 6, 7, 8). While Paris lay in ruin, France’s artist-exiles in London recorded recent modern monumental architecture meant to look medieval (the rebuilt Houses of Parliament), modern engineering (the relocated Crystal Palace), and urban design (the recently opened Victoria Embankment). Sticking close to his London home in Upper Norwood, Pissarro used the glass-and-iron shed of the Crystal Palace as a local landmark (fig. 9). Such scenes allude to the 1851 Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations when tourists and travelers (not refugees and exiles) flocked to the English capital in a celebration of cultural exchange and capitalist competition. Rather than extol London as an international or cosmopolitan center, the Impressionists’ depictions of the city skyline and people at a distance may instead signal their loneliness, isolation, and homesickness. Despite their physical distance from France and felt isolation in England, Monet and Pissarro were not entirely removed from Paris. Photographs documenting French monuments rocked by canon blasts and buildings pocked by bullet holes were collected abroad. Le Charivari soberly reported the English fascination with Paris’ modern ruins. One collector acquired 50,000 photographs of the wrecked Column Vendôme (39). Not only were images like those shown in the Tate held by private collectors, but also the London press bombarded the public with updates and etched images of burnt buildings and broken monuments.

Beating a retreat from death and destruction, many of these artists from France took refuge in the National Gallery and the British Museum, where, welcomingly, “‘heating, lighting, pens and ink were free’” (192). Wielding tourist guidebooks like London illustré that included museum and gallery maps in addition to practical information about public transit and reputable hotels, Carpeaux, Monet, and Pissarro toured the National Gallery. Their temporary relocation to London, however painful, also proved educational. It afforded opportunities to see and study collections previously only known to them through prints. Capturing the colorful commotion in Trafalgar Square, de Nittis turned his paintbrush to the crowds of locals and tourists below the elevated entryway to the National Gallery. Tissot, represented elsewhere by paintings of less academic pleasures or intellectual pursuits, similarly painted cultural tourists in London Visitors (fig. 10). His fashionably dressed country couple consult a guidebook to find their next stop, having completed their tour of the National Gallery. (In a larger version of the painting shown at the Royal Academy, the Saint-Martin-in-the-Fields clock, visible through the columned portico, strikes the early hour of 10:35 AM, indicating their brisk tour of the museum.) Compared with these tourists’ visits, artists like Carpeaux carefully studied its collections, copying paintings by Rembrandt and Correggio for later reference.

Not only did French artists diligently study the Old Masters, but also they scoured the capital for financial and exhibition opportunities to support their own art. While some—the painter and engraver Legros, medallist and sculptor Lantiéri, and sculptor Dalou—taught to supplement their income from sales and commissions, other artists concentrated on pursuing opportunities to place their work in dealer galleries and at the Royal Academy (fig. 11). Paul Durand-Ruel fled to London, where he set up shop and established the French Society that showcased mature works by Charles Daubigny and early paintings by Monet and Pissarro. Building on her essay for the 2015 exhibition Inventing Impressionism: Durand-Ruel and the Modern Art Market, Anne Robbins has here turned to the Impressionists’ exhibition strategies beyond those indebted to Durand-Ruel.[14] In their continual search for fiscal solvency and critical acclaim, they submitted their work to public and private outlets—a strategy pursued by French artists of varied artistic and political stripes. Already before the outbreak of the war, Daubigny had simultaneously participated in the Royal Academy and contracted with dealers. Scurrilous arch-opponent of the Impressionists, Jean-Léon Gérôme, whose representation has been restricted here to a bust-length marble by Carpeaux, had been appointed an honorary member of the Academy in the 1860s (fig. 12). Ex-Communard Dalou and imperialist loyalist Carpeaux were both lauded for sculptures shown at the Academy. The elderly and ill Carpeaux, who followed his humiliated patron Napoleon III to London, also sold “retrospective and reproductive works . . . at the auctioneers, Christie, Manson & Woods” (171). Monet and Pissarro were less fortunate at the Academy and on the market. Monet failed to sell a single canvas during his nine-month stay in London—this despite his friendly ties to Durand-Ruel. Pissarro had a painting refused by the Academy only to have it subsequently purchased by Tissot, whose sympathetic depiction of the Empress Eugénie and Prince Imperial Napoléon in mourning had been declined by the Royal Academy.

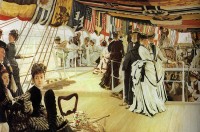

Whereas some from France struggled to earn their daily bread, others networked with elite social circles, occupying a liminal position that put them not exactly outside, but also not exactly inside those circles. A painter of modern life whose inspiration came from fashion plates and who contributed to the fashionable Vanity Fair, Tissot launched a successful career in London. In the 1870s, he produced slickly droll painterly commentaries on modern England (81) (fig. 13). Though not quite rising to the critical polemics of Edouard Manet and the Impressionists, Tissot’s paintings hinted at social and sexual anxieties. With a cheeky wink and a nod, he depicted lackadaisically chaperoned picnics attended by cricket players and their female companions, at-home concerts attended by women bedecked in bows and flounces, pleasure craft ferrying seamen, soldiers and fashionable ladies on flirtatious dalliances down the river Thames, and unfashionably early arrivals at fancy dress balls (figs. 14, 15). All this revelry in the lives and loves of the English elite maybe could be cast as a sorely needed distraction from wartime. Yet these paintings seemed to detract from the exhibition’s ostensible raison d’être: exile.

The exhibition and its catalogue have loosely labeled all these artists exiles (sometimes “self-enforced”), economic migrants, outsiders, and tourists. Despite the robust attention to each artist’s evolving aesthetic and political position, the exhibition and catalogue wrestled with how to concretely limit these charged labels. De Nittis, for instance, found himself forced to flee his adopted French homeland and relocate in London due to the military debacle. Leaving France for England, Tissot supposedly abandoned his national identity, as he “wished to be English in Paris and French in London, a paradox that renders him unclassifiable” (81). He returned to his French homeland, only after his comfortable domestic life in England had been disrupted by the death of his beloved mistress. By the final decade of the nineteenth century, as Frenchmen once more embattled Frenchmen due to rampant anti-Semitism and xenophobia sparked by the Dreyfus Affair, the artists assembled here had all achieved international critical and financial success and had returned to London. Monet’s paintings of Charing Cross Bridge, Waterloo Bridge, and Houses of Parliament were shown at the Paris Galerie Durand-Ruel in 1904 and subsequently sold on the international art market. Pissarro returned as well to paint the lush flowering lawns of Kew Gardens. André Derain, backed by Ambroise Vollard, perched his easel on the Thames embankments and there painted bridges and embankments captured by the light brushstrokes of Monet (fig. 16). By the 1890s and 1900s, these artists should be counted not as economic migrants, outsiders, or exiles but pleasure-seeking travelers and tourists taking in the city’s sights.

On its website, the EY, the exhibition sponsor, espouses a dedication to fostering a better working world.[15] Surely, that same interest should extend to the refugee and migrant communities now resettled in London and throughout the British Isles. That this exhibition, catalyzed by the Franco-Prussian War and Paris Commune when socialists, anarchists, and republicans marched side-by-side in solidarity for a brighter and fairer future, has not acknowledged the plight of Syrian refugees and African migrants currently seeking safety and security in Europe (and the United States), only underlines the need to boldly engage with the political present. The Impressionists in London has dealt with and in traumatic realities of warfare and its fallout, which the artists shown here luckily escaped. Not all were so fortunate; sadly, not all will be so fortunate. At the risk of besmirching nineteenth-century paint with present-day politics, the art shown here could be activated to critically attend today’s pressing realities. By sidestepping similarities (and, of course, differences) between historical and contemporary wartime atrocities and displaced populations, and by warning against interpretations of the exhibition in light of the recent EU Referendum and Britain’s future place in relation to the European Union, Tate Britain has timorously rendered fraught moments, past and present, apolitical:

In 1973, the Arts Council of Great Britain organized at the Hayward Gallery an exhibition entitled Impressionists in London, which formed part of ‘Fanfare for Europe’, a series of events to mark the British entry into the European Economic Community. When Tate Britain and the Petit Palais decided four years ago to join forces to bring to fruition our own cross-channel project, the outcome of the EU Referendum was still ahead of us. Any resonances arising from the shared exhibition title and the current political context, therefore, are purely coincidental.[16]

Rarely are intersections between paint and politics coincidental. To conclude with John House’s considered comments on the 1973 Hayward Gallery The Impressionists in London, “an exhibition like this can suggest many new perspectives and ways of approaching paintings.”[17] An exhibition like the current The Impressionists in London, French Artists in Exile (1870–1904) suggested still many more new perspectives and ways of approaching painting and other media (sculptures, medals, photographs, sketchbooks, and works on paper). It hinted at new ways of approaching the history of art history. And, intentionally or not, it underscored the need to attend to politics situated in the past but still so urgently present.

Alexis Clark

Washington University in St. Louis

alexis.clark[a]wustl.edu

[1] John Rewald, The History of Impressionism (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1973); T.J. Clark, Absolute Bourgeois: Art and Politics in France, 1848–1851 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1973); T.J. Clark, Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution (London: Thames and Hudson, 1973).

[2] John House, Review of The Impressionists in London, The Burlington Magazine 115, no. 840 (March 1973): 194.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Eric Shanes, Impressionist London (New York: Abbeville Press, 1994), 15. As Shanes has explained, “only a few plein-air studies by the major British landscapists could have been seen by the French Impressionists, for they were rarely shown in museums until late in the nineteenth century. Yet the authenticity of vision that they demonstrated spilled over into many of the exhibited.” One painting that likely did influence Monet and Pissarro, however, was Turner’s Rain, Steam and Speed—The Great Western Railway that could be seen in the National Gallery due to the Turner Bequest, which had left that institution more than 300 oil paintings and 30,000 sketches. Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who did not relocate to London during the Franco-Prussian War, may have fallen under the influence of Constable and Turner in 1883, when he supposedly attended Durand-Ruel’s London exhibition of his paintings. More, Corbeau-Parsons has contended that French exiles were not at all interested in modern British art, with some exceptions: Tissot “deeply admired” John Everett Millais and Whistler (he defined as a British artist); Monet and Pissarro appreciated G.F. Watts and Dante Gabriel Rosetti. See “Crossing the Channel,” 18–19.

[5] I here include Gustave Caillebotte, Mary Cassatt, Paul Cézanne, Monet, Berthe Morisot, Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Sisley as the eight or nine artists often labeled Impressionist. Historically, Cassatt’s American nationality has troubled her association as an Impressionist.

[6] A discussion of the translations of Burty and Mallarmé may be found in Charles S. Moffett, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886 (Geneva, 1986).

[7] Unsigned Review, The Times (April 25, 1876), 5 in Kate Flint, Impressionists in England: The Critical Reception (London: Routledge, 1984), 36.

[8] Camille Mauclair, The French Impressionists (London: Duckworth, 1903). Interestingly, this book appeared before Mauclair’s French-language book on Impressionism: L’Impressionnisme: Son histoire, son esthétique, ses maîtres (Paris: Librarie de l’art ancient et moderne, 1904). See also Théodore Duret, Manet and the French Impressionists (London: Grants Richards, 1910).

[9] Flint, Impressionists in England, 11.

[10] Ibid., 12. Confirming the disparate definitions of “Impressionism” in circulation throughout English art and literary circles, Shanes has written that “many British writers on art added confusion to ignorance by loosely employing the term impressionist to describe any painter who expressed sensory responses or vague, dreamy impressions of things, rather than delineating appearances in meticulous detail. For that reason Whistler was generally considered to be an Impressionist—and even the ‘master’ Impressionist, as he was characterized in 1891 by Oscar Wilde, who equated Whistler’s fogs with vaguely defined forms, which in turn he equated with Impressionism. Similarly, many British painters, such as George Clausen, Stanhope Forbes, Henry La Thangue, and John Lavery, were considered Impressionists, even though they were followers of Jules Bastien-Lepage, who was himself a follower of Manet rather than an Impressionist.” See Shanes, Impressionist London, 140.

[11] De Nittis had shown at the first exhibition and Legros had shown in the second exhibition of the Société anonyme.

[12] Hollis Clayson, Paris in Despair Art and Everyday Life under Siege (1870–1871) (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002). In his essay for The Impressionists in London catalogue, Bertrand Tillier has recounted the participation of artists in the National Guard: “Puvis de Chavannes, Eugène Carrière, Gustave Caillebotte, Gustave Doré, James Tissot, Georges Clarin, Léon Bonnat, Edouard Detaille, and Alphonse de Neuville. Manet, with the rank of lieutenant, was a first gunner in the artillery before being posted to the headquarters, where he served under Meissonier. Degas also joined the National Guard.” Tillier has proceeded to describe the wounds, some of them mortal, sustained by French artists on the battlefront: “At the Battle of Champigny the painter Félix Ziem was hit by a bullet that broke his leg. Another painter, Georges Vibert, was injured at Malmaison, where the sculptor Joseph Cuvelier was also killed. . . . Frédéric Bazille’s death at the age of twenty-eight, on 28 November 1870, at the Battle of Beaune-la-Rolande was felt very painfully by the future impressionists. . . . Above all, Henri Renault’s death on 19 January 1871 at Buzenval . . . caused immense emotion among artists.” See Bertrand Tillier, “Painters Tested by the Terrible Year (1870–1)” in The Impressionists in London, French Artists in Exile (1870–1904), ed. Caroline Corbeau-Parsons (London: Tate Publishing, 2018), 24.

[13] Ibid., 13.

[14] Sylvie Patry, ed., Inventing Impressionism: Paul Durand-Ruel and the Modern Art Market (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015).

[15] EY was formerly a financial investment and accounting firm named Ernst & Young.

[16] Corbeau-Parsons, “Foreword,” 7.

[17] House, Review, 197.