The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Wilhelm Lehmbruck: Retrospective

Leopold Museum, Vienna

April 8, 2016 – July 4, 2016

Catalogue:

Wilhelm Lehmbruck: Retrospektive | Retrospective.

Hans-Peter Wipplinger, ed.

With contributions by Hans-Peter Wipplinger, Söke Dinkla, Bazon Brock, Franz Smola, Marion Bornscheuer and Stefan Kutzenberger; republished material by Wilhelm Lehmbruck and Joseph Beuys.

Cologne: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2016.

255 pp.; 202 color illus.; 39 b&w illus.; biography; checklist of exhibition.

€ 29.90 (softcover German/English edition) English translation by Agnes Vukovich.

ISBN: 9783950301885

Sculpture is the essence of things,

the essence of nature,

that which is eternally human.

Wilhelm Lehmbruck.[1]

Last year, the Leopold Museum in Vienna brought together around fifty-five sculptures and some one hundred paintings, drawings and etchings by the artist Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881–1919) in a tasteful and informative exhibition. All his major works were represented and placed in illuminating dialogues with works by Lehmbruck’s models, contemporaries, and followers. This retrospective exhibition on Lehmbruck marked the curatorial debut of Hans-Peter Wipplinger as artistic director of the Leopold Museum.[2]

In his foreword to the exhibition catalogue, director Wipplinger accurately defines the exhibition’s aim. As is often the case, the aspiration is to demonstrate the artist’s rightful place in the art historical canon as “one of the most important of his time.” Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s chief quality was his ability to convey “a deeply humanitarian message,” and the importance of his oeuvre is its function as a “preface to Expressionism in sculpture” (5). Söke Dinkla, the director of the Lehmbruck Museum in Duisburg, elaborates on this claim of significance. She states that the work of Lehmbruck has shaped our image of man in the early twentieth century. People of all backgrounds feel the spiritual and emotional intensity of the artist’s universal and timeless “icons of inner life” (9–11).

The exhibition labels are to the point and elucidate the artworks on display. Based on the catalogue contribution of director Wipplinger, the introductory label to the exhibition heralds Wilhelm Lehmbruck as an “important innovator and pioneer of modern European sculpture.” The exhibition displays Lehmbruck’s artistic development in a chronological presentation that is enriched with a multitude of works by other artists. In doing so, the curators established an engaging dialogue between Lehmbruck and his role models, contemporaries, and followers.

Wilhelm Lehmbruck was born in 1881 into a poor mining family in Germany’s industrial Ruhr region. He enrolled at the Düsseldorf School of Arts and Crafts at the early age of fourteen. When his father passed away in 1899, Lehmbruck quit school and worked as an apprentice in sculpture workshops. At the age of eighteen he enrolled at the Düsseldorf Academy of Arts where he was educated in naturalist and classical sculptural traditions until 1906. As is true for many young artists, his early work is characterized by unsettled experimentation and a plurality of styles. Bust of a Young Woman (1901), Grace (ca. 1902–1904) and an early self-portrait of 1908 are exemplary of this (fig. 1).

Nine months after Lehmbruck’s marriage to Anita Kaufmann in 1908, his young wife gave birth to the first of their three sons. It was around this time that Lehmbruck reflected on the relationship between mother and child in a range of sculptures as well as drawings. In the treatment of this subject, the influence of Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) is manifest. Lehmbruck was immensely impressed by the work of the great pioneer of modernist sculpture when he first encountered it in 1904 at the International Art Exhibition in Düsseldorf. The expressive gesture of Mother, Protecting her Child (1909) reveals the influence of Rodin who was a master in making emotions of all kinds tangible (fig. 2). As for Rodin, the “flickering restlessness of a pain directed inwards” is a core element in the work of Lehmbruck (19). The same subject was also of great importance to Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945), whose moving Mother with Two Children (1923–37) is exhibited side by side with Lehmbruck’s Mother, Protecting her Child and Mother and Child (1907) (fig. 3). Together, they make a stunning ensemble.

A socio-critical theme Lehmbruck was concerned with in his early career is milieu studies of the proletariat in which he addressed the tough working conditions of the laborers in his native region. Works like the relief Sitting Miner with Miner’s Lamp (1905) bear close resemblance to the oeuvre of Constantin Meunier, whose Puddler (1894/95) is included in the exhibition (fig. 4). The relief shows Lehmbruck’s ability to convincingly express the strength of the masculine physique of his laborers. In the years to come however, Lehmbruck would focus on the female figure in his sculptures.

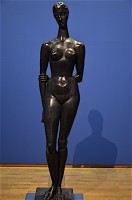

The exhibition visitor is now guided along Lehmbruck’s “path towards a new modernism”, as the following section is entitled. Lehmbruck made his debut at the German Art Exhibition in Cologne in 1906 where he gained recognition with Bathing Woman (1902–05). From then on, Lehmbruck exhibited at multiple occasions, including the Paris Salon of 1907, which marked his first trip to the French capital. In 1908, Lehmbruck had the chance to meet Aristide Maillol (1861–1944) in his Paris studio. He was deeply impressed by Maillol’s concentration on corporeality and his de-dramatization of form (19) (fig. 5).

In 1910, the Lehmbruck family relocated to Paris. Here, the artist quickly became a prominent presence at exhibitions. He not only exhibited at the Salon, but also at the Salon d’Automne and the Salon des Artistes Indépendants. He was well connected and counted many cultural figures among his associates including Alexander Archipenko (1887–1964), Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920), Ossip Zadkine (1890–1967) and Henri Matisse (1869–1954). Works by all of these artists are included in the exhibition (fig. 6). Especially appealing is Flat Torso (1914) by Lehmbruck’s dear friend Archipenko. It was in Paris, under the influence of these new progressively oriented contacts, that Lehmbruck slowly but surely broke away from his role models Rodin and Maillol. For many German artists who came to Paris, it was actually through their presence in the French capital that the art of the great Rodin and Maillol became less exceptional and consequently less worthy of imitation.[3]

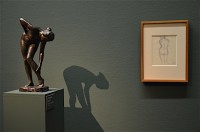

Overcoming your masters is a precondition to arrive at one’s individual style. Through a range of sculptures, drawings, etchings, and even paintings concerned with a very limited range of subjects (e.g. bathing woman; standing female figure; girl with propped-up leg), Lehmbruck arrived at his own modern style (fig. 7). That is to say, he did not simply copy his role models Rodin and Maillol, or the equally important German painter Hans von Marées (1837–87); he assimilated their characteristic features into entirely personal new sculptural concepts, as Julius Meier-Graefe admiringly determined in 1912.[4]

His Large Standing Figure (1910–12) is considered the demarcation between his early, academically influenced body of work, and his much more personal, stylistically formulated main oeuvre which made him one of the important innovators of European sculpture (fig. 8). Around 1910, Lehmbruck arrived at a new sculptural expression that was defined by a sensitive corporeality and increasingly expressive gestures. The following years are characterized by a process of progressing fragmentation, explored in depth in various media such as Susanna (1913) and Woman Looking Back (1914) (fig. 9). From then on, Lehmbruck continuously examined the importance of individual limbs as sculptural formal elements in relation to the whole; reducing figures to torsos and busts to mere heads (23) (fig. 10). Taking further and further his conviction that “all art is measurement,” for the proportions “determine the impression, the effect, the physical expression [etc.] and everything else.”[5]

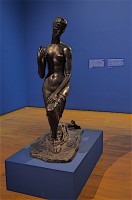

Lehmbruck experienced his international breakthrough in 1913 when his Kneeling Woman (1911) and Large Standing Figure were exhibited at the renowned Armory Show in New York (fig. 11). By then, he could count on favorable press coverage by influential figures like Julius Meier-Graefe and Paul Westheim. Kneeling Woman represents a creative paradigm shift. This stylistically groundbreaking work was celebrated as the preface to Expressionism in sculpture as early as 1916. With this sweeping larger-than-life female figure, Lehmbruck had moved away from any references to classicism or his earlier role models to an unprecedented extent (25). In his continuous personal challenge to arrive at art that is a materialization of the spirit, Lehmbruck created a body of work that consists of creations that are unmistakably recognizable.

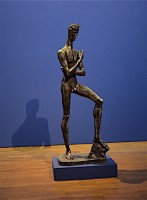

Only a few years later, the captivating Kneeling Woman was eclipsed by Ascending Youth (1913/14) and its female counterpart Pensive Woman (1913) (figs. 12, 13). Both of these larger-than-life figures are “invested with a formal tension reflecting the dualism of spirit and matter, [of] body and soul” (27). This deeper meaning might not be intellectually comprehensible for every visitor, but it is unquestionably felt on a different level, experienced with one’s senses. The spatial presence of Ascending Youth is undeniable and as such this artwork simply demands a reflective observation from the viewer. It is a known fact that most artworks are viewed by museum visitors for mere seconds. It is difficult, however, to simply stroll past this gripping youth. With his less-is-more approach to form, Lehmbruck achieved maximum effect with regard to expression and intensity. Ascending Youth, with its elongated proportions, slender torso, and large head, is deeply moving.

Ascending Youth and Pensive Woman were both created shortly before the outbreak of the First World War. Everything about Ascending Youth signals progress; the figure strives forwards and upwards, both physically and mentally (71). The work is a positive allegory of the spiritual reflection on human existence. At the time he created it, Lehmbruck had fully grown into his own as an artist and expressed an optimistic perspective on what was to come:

I believe that we are once again heading for truly great art, and that we will soon find the expression of our time in a monumental, contemporary style . . . heroic like the spirit of our times.[6]

The all-encompassing disillusion that followed soon after could not have been greater. This fruitful period in Lehmbruck’s career came to an abrupt end with the outbreak of the war. Shortly after his first solo exhibition in Paris in June 1914, the Lehmbruck family was forced to leave France, and relocate to Berlin. Lehmbruck was employed as an orderly at a medical hospital where he experienced firsthand the horrors of war. Through his connections, however, he managed to arrange work as a war painter instead. But soon after he got permission for this resettlement, he was dismissed from military service due to his difficulty in hearing.

The Fallen Man (1915) is equally moving and intense, but in every respect the antithesis of Ascending Youth (fig. 14). This sculpture is an allegory of despair and, like many drawings, prints and paintings of around the same time, it depicts humanity threatened in its very existence. The Fallen Man was, and is, in essence a memorial against war (29). Such discouragingly dismal expressions were not at all appreciated in the early years of “The Great War,” and Lehmbruck consequently faced harsh criticism. However, not all was bad for Lehmbruck during the war years. It would be a misconception to assume that all cultural activity came to a halt during the war.[7] Renowned gallerist Paul Cassirer represented the artist from 1916 onward, which ensured a modest, but solid income. Also, the largest exhibition of Lehmbruck’s work during his lifetime took place in Mannheim in 1916.

Nevertheless, according to a close relation in Berlin, Lehmbruck experienced “a secret ache” and “went through an artistic crisis” during these years. By late 1916, Lehmbruck decided to await the end of the conflict in Zurich, which had become the refuge for many Europeans who opposed the war (29). Here, he soon counted different authors and actors among his friends. And it was during a performance of Tolstoy’s play The Living Corpse (première in 1911) that Lehmbruck fell madly in love with young actress Elisabeth Bergner (1897–1986). His love for her remained unanswered; Praying Woman (1918) expresses Lehmbruck’s desire for Bergner (fig. 15). Although a lot of attention is given to the relatively short episode of Lehmbruck’s infatuation with Bergner, his wife Anita Kaufmann remains a mystery figure. One only finds a short remark about her significance in the catalogue’s biography: Early in their marriage, when the couple had just moved to Paris, Anita was Lehmbruck’s primary model. And even more interesting, she managed the business side of his exhibition participation and the sale of his artworks (239).

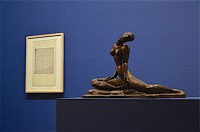

One last highlight of Lehmbruck’s oeuvre is the intensely expressive bust Head of a Thinker (1918), which is widely interpreted as a metaphorical self-portrait (fig. 16). A distinctive feature of Lehmbruck’s oeuvre is that his works are usually far removed from any concrete occurrence and should rather be conceived as materializations of the spirit. Head of a Thinker exemplifies this. The work also illustrates the interesting notion that Lehmbruck is always referencing abstraction without ever actually realizing it (41). Pieta (2008) by contemporary artist Berlinde De Bruyckere is displayed in close vicinity to Head of a Thinker and serves as a compelling intervention.[8] The fragmentation of the human body that is characteristic for the (late) oeuvre of Lehmbruck is a recurring aspect in the work of De Bruyckere, who also addresses existential themes of human existence.

While living in Zurich, Lehmbruck’s depression deepened. His restrained marriage, Bergner’s rejection, his war experiences, but probably most of all his overall sense of alienation from a shattered world all added up to his deteriorating mental state. Following the end of the war, he returned to Berlin in 1919 where he was appointed a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts; the highest recognition for a German artist. Lehmbruck committed suicide on March 25, 1919.

The catalogue consists of six essays, a small selection of poems by Lehmbruck and a reprint of the speech made by Joseph Beuys when he was rewarded the Wilhelm-Lehmbruck-Prize in 1986. The first essay by Hans-Peter Wipplinger is the most important one in relation to the exhibition as it offers a better understanding of the connections made between Lehmbruck and other artists in the exhibition. The essayistic contribution of Bazon Brock, who describes himself as thinker in service and artist without oeuvre, provides food for serious thought about the significance of Lehmbruck’s ongoing quest to embed his sculptures with a metaphysical dimension.[9] An astute observation made by Brock is that creation through detraction is a key feature of Lehmbruck’s oeuvre (35).

Curator and head of the museum’s library Stefan Kutzenberger sheds light on Lehmbruck’s relation to literature. Lehmbruck, an avid reader, often engaged with literary motifs. And there were many authors among his close associates, especially when he was living in Zurich during the war. As is often the case due to the proximity to the written word, he found the graphic print the medium par excellence to render visible literary themes. What’s more, Lehmbruck himself wrote a modest number of expressionist poems. A few of these are printed in the exhibition catalogue, a section of one of which is quoted at the very end of this review.

The essay of collections curator Franz Smola offers insight into the reception of Lehmbruck by Austrian sculptors in the early twentieth century. As such, Smola’s contribution complements that of Wipplinger. With the exception of a few prints, Lehmbruck’s work was never present in Austria during his lifetime. In the 1920s and 1930s however, Lehmbruck’s work was exhibited in Austria on multiple occasions, and the expressionist nature of his body of work influenced a whole range of Austrian artists. Smola illustrates this through the work of Josef Humplik (born 1888), Siegfried Charoux (born 1896), Georg Ehrlich (born 1897), Franz Hagenauer (born 1906) and Fritz Wotruba (born 1907). Unfortunately, none of these artists is featured in the exhibition itself. This would have added an interesting extra dimension to the understanding of Lehmbruck’s significance, and his impact on Austria’s art world.

An Austrian artist that is widely represented in the exhibition is Egon Schiele (1890–1918). This is to be expected from the museum that holds the largest collection of Schiele’s work in the world. The two artists complement each other beautifully, and their corresponding subject matter completely justifies this artistic encounter. Schiele and Lehmbruck were actually exhibited side by side in a dual exhibition at the Folkwang Museum in Hagen as early as 1912.[10] Schiele expressed his appreciation for Lehmbruck around the time of the founding of the New Secession Vienna in July 1918, when he envisaged an exhibition that would include Lehmbruck’s work. Schiele’s high opinion of Lehmbruck as being of great international significance, is quite striking, as Lehmbruck’s big breakthrough in the German-speaking world only occurred after his death in 1919 (55). Schiele almost certainly only knew Lehmbruck’s work through reproductions.

In her essay, curator of the Lehmbruck Museum Marion Bornscheuer examines whether Schiele and Lehmbruck can be considered kindred spirits. She claims that both artists were motivated by a search for universal awareness of the self (71). Formally, there are many striking similarities between the two artists. Examples that spring to mind are the elongated or otherwise disproportioned physique of their figures, and the highly expressive character of their work (fig. 17). What they achieved by employing these means of expression is however antipodal. Bornscheuer explains that in Lehmbruck’s sculptures, the spirit triumphs over the body, whereas for Schiele, the mind is ultimately defeated by the body (67). What I find interesting is that the two artists experienced opposite developments. Lehmbruck gained recognition at an early stage, but became increasingly troubled later on which is clearly reflected in his work. For Schiele it was the other way around; misunderstood and struggling with his self-image in his early years as an artist, Schiele grew more and more confident over the years, which evidently impacted his work.

For the finale of both the exhibition and the catalogue, the floor is given to Joseph Beuys (1921–86). Upon accepting the Wilhelm-Lehmbruck Prize on January 12, 1986, Beuys gave a speech entitled “Thanks to Wilhelm Lehmbruck,” in which he expounded on the great importance of Lehmbruck for his own work, noting that Lehmbruck carried the tradition of sculpture from Rodin to a climax of inwardness, to a body of work that can only be understood intuitively, not just by observing it, but through hearing, contemplating, and wanting (107). It was this sensory experience that led Beuys to his own so-called social sculpture, in which he united his idealistic ideas of a utopian society with his aesthetic practice.[11] Beuys’ speech is reprinted in the catalogue and a video of his talk was displayed in the final exhibition room dedicated to the kinship between Beuys and Lehmbruck (fig. 18).

In her second contribution to the catalogue, Bornscheuer accurately explains how the graphic oeuvre of both artists gradually changed from “depicting external elements towards depicting internal, expressive ones.” Their intuitive and tentative quest for the ideal sculptural form is what binds Lehmbruck and Beuys (93; 99). In the exhibition, the relation between Beuys and Lehmbruck is also explored through the medium of drawing. Both artists considered their drawings as thought forms, and as such they are challenging objects to exhibit. The drawings are all rather sketch-like and generally devoid of color (fig. 19). Due to their unobtrusive appearance, they can be easily overlooked by the visitor. In this display however, their highly expressive quality is emphasized and even enhanced by their joint presence.

This exhibition dedicated to Wilhelm Lehmbruck was both beautiful and informative. It really was a retrospective exhibition with all of the artist’s major works present. What’s more, Lehmbruck, who is first and foremost known as a sculptor, was also represented with a multitude of works in other media. The curators stressed that for Lehmbruck, his drawings, prints, and paintings were on a par with his sculpture (fig. 20). Including them was a good decision as it greatly enhanced the understanding of the artist’s development. It is undeniable, however, that his sculptures are the most impressive, unique, and thought-provoking works within his oeuvre.

One general point of critique is that a more extensive connection could have been made between the catalogue contributions and the exhibition. It would have been worthwhile if the authors had the opportunity to build their story (like the comparison between Schiele and Lehmbruck, or the impact of Lehmbruck on Austrian artists) using more art works that were actually part of the exhibition.

Because of the many juxtapositions with other artists, ranging from a role model like Rodin to the contemporary artist Berlinde De Bruyckere, the exhibition was very rich in content. On paper, this approach might seem too heterogeneous. But because of Lehmbruck’s strikingly distinguishable oeuvre and the fact that it consists of a limited number of oft-repeated motives, the exhibition as a whole was very comprehensible. In fact, the inclusion of related works by other artists greatly contributed to the understanding of Lehmbruck and his time.

Interestingly enough, the exhibition is imbued with an overarching message. The introductory label to the exhibition concludes as follows:

The oeuvre of Lehmbruck, which is shaped by a profound humanity is of eminent importance not only from an art historical perspective but, in light of current global politics such as war, terror and displacement, is still highly relevant today.

It is quite unusual for exhibitions dedicated to nineteenth-century or early twentieth-century art to make such an explicit connection to contemporary society. What this statement strongly suggests, is that the exhibition makers see some parallels between the years leading up to the First World War and the present. They are not alone in this.

Art has the ability to reflect on society from a higher level, and perhaps even to forewarn. Together, Lehmbruck’s Ascending Youth of 1913/14 and The Fallen Man of 1915, made just before and during the First World War, symbolize the devastating effect of war, terror, and displacement. Whereas Ascending Youth signifies confidence in the progressive development of individual man and society as a whole, The Fallen Man embodies all encompassing despair. By including this statement in the introductory label, the exhibition makers present the work of Lehmbruck as an antidote and warning, and rightly so.

Faith and love are all destroyed,

And death lies on every path and every flower.

O curse, I curse you a thousand times!

Have you, who have sown so much death,

Not death

For me too?

Wilhelm Lehmbruck, 1918[12]

Lisa Smit

Art historian

I am most grateful to curator Stefan Kutzenberger of the Leopold Museum for his attentive support in the formation of this review.

[1] Wilhelm Lehmbruck, “Fragmente,” in Paul Westheim, Wilhelm Lehmbruck (Potsdam-Berlin: 1919), 61. Reprinted in the exhibition catalogue (jacket flap).

[2] This exhibition was made possible thanks to the cooperation of the Lehmbruck Museum in Duisburg that houses almost the entire oeuvre of the artist. It was the first extensive Lehmbruck exhibition to take place in Austria since 1963 when the first solo exhibition was held at the Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts in Vienna.

[3] Susanne Kähler, “Deutsche Bildhauer in Paris: Die Rezeption französischer Skulptur zwischen 1871 und 1914 unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Berliner Künstlerschaft” in vol. 278 of Europäische Hochschulschriften: Reihe XXVIII – Kunstgeschichte (Frankfurt am Main; New York: Peter Lang, 1996), 188.

[4] Julius Meier-Graefe, “Pariser Reaktionen,” Kunst und Künstler, vol. 10 (1912): 448. Quoted in the exhibition catalogue (19). Meier-Graefe bought Lehmbruck’s Small Female Torso (Hagen torso) (1910/11) at the Salon d’Automne of 1911.

[5] Wilhelm Lehmbruck, “Lehmbruck über Plastik. Mitgeteilt von Paul Westheim,” in August Hoff‚ “Wilhelm Lehmbruck,” Junge Kunst, vol. 61/62 (1933), 20. Quoted in the exhibition catalogue (23).

[6] “Ich glaube, daß wir wieder einer wirklich großen Kunst entgegengehen, und daß wir bald den Ausdruck unserer Zeit finden in einem monumentalen, zeitgemäßen Stil. . . . heroisch, wie der Geist unserer Zeit.” Quoted from an undated manuscript by Wilhelm Lehmbruck. Published in Christoph Brockhaus, “Gedichte und Gedanken,” Wilhelm Lehmbruck, 1881–1919: Das plastische und malerische Werk: Gedichte und Gedanken, coll.cat. of Stiftung Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum – Zentrum Internationaler Skulptur (Cologne: Wienand, 2005), 282.

[7] The international conference “14|18 Rupture or Continuity: Belgian Art around World War I” that took place at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium on November 24–25, 2016 was dedicated to the nuancing of the assertion that World War I was a caesura. Countering the idea that artistic production came to a halt and that modes of artistic expression completely changed due to the war.

[8] Parallel to the Lehmbruck retrospective, a solo exhibition dedicated to contemporary artist Berlinde De Bruyckere (born 1964) was taking place at the Leopold Museum. Two of the artist’s sculptures were incorporated in the Lehmbruck exhibition, a clever way to connect simultaneous presentations.

[9] Bazon Brock defines himself as “Denker im Dienst und Künstler ohne Werk.” See: http://www.bazonbrock.de/bazonbrock/, accessed November 5, 2016.

[10] Lehmbruck failed to meet his deadline for the exhibition planned for February 1912 at the Folkwang Museum in Hagen. Consequently, Lehmbruck and Schiele were exhibited side by side in April. Lehmbruck was represented with five sculptures, five paintings, and several etchings. Of Schiele’s work, eight paintings and a large selection of drawings were exhibited. Neither Lehmbruck nor Schiele attended the dual exhibition in Hagen.

[11] Social sculpture is a theory developed by Beuys in the 1970s based on the concept that everything is art, that every aspect of life could be approached creatively, and as a result, everyone has the potential to be an artist. Social sculpture united Beuys’s idealistic ideas of a utopian society together with his aesthetic practice. He believed that life is a social sculpture that everyone helps to shape. Definition from the illuminating illustrated Glossary of Art Terms of the Tate galleries. See: http://www.tate.org.uk/learn/online-resources/glossary/s/social-sculpture, accessed November 6, 2016.

[12] Final phrases of the poem Wer ist noch da? (Who is Still There?) of 1918: “Der Glaube, Liebe, alles hin, / Und Tod, er liegt auf allen Wegen, auf jeder Blüte. / O Fluch, o tausendfacher Fluch! / Habt ihr, die soviel Tod bereitet, / Habt ihr nicht auch den Tod / Für mich?” Quoted in Paul Westheim, Wilhelm Lehmbruck (Potsdam-Berlin: 1919), 62. Reprinted in the exhibition catalogue (91).