The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Alma-Tadema, klassieke verleiding (Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity)

Fries Museum, Leeuwarden, Netherlands

October 1, 2016 – February 7, 2017

Belvedere, Vienna

February 24 – June 18, 2017

Leighton House, London

July 7 – October 29, 2017

While on vacation in Amsterdam over Thanksgiving week, my partner and I took a day trip to Leeuwarden to see the exhibition Alma-Tadema, klassieke verleiding at the Fries Museum.[1] As a scholar and fan of British and Victorian art, naturally I was eager to see this exhibition on Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912), not having had the opportunity to see the last major retrospective of his work twenty years earlier at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool.[2] This new exhibition focused on three themes: the cinematic appreciation of Alma-Tadema by filmmakers of the twentieth century; a more detailed understanding of his early years and training in The Netherlands and Belgium; and the role of the artistic home that he and his family cultivated in London. Although we had heard that the exhibition was popular, we were startled by the large number of visitors there to see the art of this Victorian painter on a Tuesday afternoon.

About five weeks after the exhibition opened, the Fries Museum announced that it was already the most popular show in its nearly two-hundred-year history, with over 50,000 visitors in the first month.[3] The excitement about the exhibition actually began in Amsterdam itself, with banners depicting toga-clad women fluttering in the wind near the Rijksmuseum and the Van Gogh Museum, and in shops throughout the city selling copies of the exhibition catalogue in Dutch. Taking the train from Amsterdam Zuid, we saw posters with the artist’s colorful, classical figures hung in the station and on the train. During the trip of just over two hours, as the train made its way northeast around lakes Markemeer and IJsselmeer, the cars grew more and more crowded as people boarded at each stop along the way. Everyone alighted in Leeuwarden and made their way to the Fries Museum. On the short walk from the station, cafes advertised Victorian—and “Alma-Tadema”—themed food options, including tea and scones, and more banners with his classical-themed paintings guided visitors toward the museum.

Although the general public may not recognize Alma-Tadema’s name, most are familiar with posters and digital reproductions of his paintings depicting “Victorians in togas” (a pejorative phrase tied to the 1973 exhibition of his work). This new exhibition, however, was an opportunity for viewers to examine closely more than one hundred of his paintings, watercolors, drawings, and decorative arts, and in so doing allow for viewers to consider the artist’s works in light of the recent spike in his popularity. Alma-Tadema’s renewed fame culminated in 2010 with the auction of his painting The Finding of Moses, 1904, which sold for an astounding $35.9 million, more than ten times the low estimate range (fig. 1).[4]

Designated as the European Capital City of Culture for 2018, Leeuwarden is a small, charming city with picturesque canals dotted with boats and streets lined with an array of historic buildings and contemporary architecture. The Fries Museum is sleek in its modern Dutch design by architect Abe Bonnema; it opened to the public in 2013 and dominates the Wilhelminaplein (fig. 2). Within the lobby of this contemporary structure, blending surprisingly well within this glass-and- white-cube environment, was an enormous wall mural advertising the exhibition, utilizing the artist’s painting Coign of Vantage, 1895 (fig. 3). The larger-than-life poster set the stage for what was on display in the exhibition galleries. The queue, first for tickets and then to get into the galleries, was remarkable (fig. 4).

Seeing all the advertisements and the crowds for an exhibition in a small city of The Netherlands on an artist considered by most to be a British Victorian painter was, to say the least, uncanny. Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema actually was born in Friesland as Lourens Alma Tadema and grew up in Leeuwarden, hence the association and importance of this city to their native son. Alma-Tadema only made his way to London in 1870, but he remained there the rest of his life. He was knighted in 1899 and buried in St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1912. He and his family donated works of art to the Fries Museum over the years, helping to support their mission of collecting artifacts and art works associated with Frisian culture and its people, ultimately making that institution the largest public repository of Alma-Tadema’s art in The Netherlands. Honoring his legacy, then, this exhibition clearly had a nationalistic focus for Leeuwarden, seeking to expand its profile internationally as an important arts center.

Nationalistic pride alone, however, cannot explain why the Alma-Tadema exhibition was so popular with thousands of people traveling tens and hundreds of miles to see his work. Clearly there has to be more to an artist’s oeuvre than patriotic identity, especially when none of Alma-Tadema’s paintings depict Frisian or Dutch culture. Over the past few decades, there has been a great rise of interest in the art of his contemporaries in Victorian London, with the Pre-Raphaelites in particular drawing audiences worldwide into museum galleries (even if some critics still denigrate their art as degenerate when compared to French Impressionism).[5] Alma-Tadema is best categorized as being part of the Aesthetic Movement, which developed in London during the 1870s and 1880s and included among its adherents the painters Edward Burne-Jones, Frederic, Lord Leighton, and J.A.M. Whistler. Indeed, Alma-Tadema’s interest in interior design and the artistic home arguably makes him even more an Aesthete than some of his contemporaries. But while this aspect of his artistry as a Victorian and Aesthete was apparent in the exhibition, it alone could not explain the popularity of the show either.

I made two observations that may help explain the popularity of the exhibition and Alma-Tadema’s paintings. The first of these was the cinematic impact of his work, a theme that was announced upon entering the museum by the wall mural, suggesting the larger-than-life sensation of his work. The first gallery in the exhibition showed digital images of his paintings with projected stills from various films, noting the influence of Alma-Tadema on filmmakers of the twentieth century. This was exemplified further in the last gallery where brief film clips, from Quo Vadis? (1913) to Gladiator (2000), were projected over related paintings hung along the outer walls (fig. 5). The similarities of visual details in the paintings and film clips were often startling, but in other instances were just referential. Although the wall texts sought to justify this direct association between the films and Alma-Tadema’s paintings, no evidence of actual consultation of specific paintings by the filmmakers was provided. For more detailed information on this, one needed to consult an essay in the catalogue by Ivo Blom, which explores how and when these visual references were more or less direct.[6] For the purposes of the exhibition, though, the visual presentation of the film clips sufficed to argue the curators’ point that there is a cinematic effect to Alma-Tadema’s work and that it influenced filmmakers in various ways.

The second reason for the popularity of the exhibition was the performative value inherent in Alma-Tadema’s paintings. By “performative” I mean that the scenes shown in the paintings encouraged viewers to interact with them. Most visitors to the exhibition stopped to look closely and intently at the figures in the artist’s pictures. They pointed to individual characters and their actions. Even more remarkable was that some viewers would turn to their families and friends and actually pose alongside or in front of the paintings, imitating the figures themselves.[7] Although clearly intended for comedic purposes, this form of self-identification with these “Victorians in togas” made me realize that the audiences in fact did not see them as “Victorians” at all, but rather as themselves in costumed attire. Their own engagement with these pictures transformed the quotidian nature of Alma-Tadema’s scenes into universal sentiments that the viewers could identify with, drawing a direct line from their own lives to the imagined lives of ancient Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians from two millennia ago, not to mention the unacknowledged lives of the models depicted therein from more than a century ago.

These observations on the cinematic and performative values in Alma-Tadema’s works made me wonder about the reception of the artist as the painter of “Victorians in togas.” This phrase was the title of the 1973 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Victorians in Togas: Paintings by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema from the Collection of Allen Funt.[8] Guest-curated by Christopher “Kip” Forbes, a champion of the study and collecting of Victorian art and culture since the 1970s, the exhibition brought together thirty-five paintings by Alma-Tadema, almost all of which were Greco-Roman in style and/or subject, and most of which were also included in this 2016–17 exhibition. In his introduction to the small catalogue, illustrated with black-and-white images, Forbes noted the cinematic appeal of Alma-Tadema’s work, not just in what he painted, but also in how his works would have been received by viewers. For instance, he wrote about how some major paintings in the nineteenth century (not necessarily those by Alma-Tadema) were shown in venues where one had to purchase tickets to see them, and how they subsequently traveled to other cities, not unlike the history of cinema in the twentieth century.[9] In a limited number of pages, Forbes presented a scholarly assessment of Alma-Tadema’s work, providing narratives about each painting along with provenance, exhibition history, and literature whenever possible.

This elevation of Alma-Tadema’s art to a scholarly status arguably was necessary, not just because British Victorian painting was still then largely dismissed by the international art community as banal, but also because the collection was owned by Allen Funt, the television producer best known for hosting Candid Camera. In the Foreword to the catalogue, Funt acknowledged that these paintings were acquired for their “decorative quality” which has “made them very liveable,” and that his first purchase of an Alma-Tadema painting was “more a piece of decoration than a work of art.”[10] So much for seeing Alma-Tadema as an important artist! In a review of the 1973 exhibition, James R. Mellow wrote that the “resurrection” of Alma-Tadema’s works revealed that “they look[ed] like nothing so much as paintings of eminent Victorians unaccountably transported back to the banks of the Tiber”; his reputation was extinct “except for devotees of camp”; and ultimately the exhibition was “refreshing camp, a high-minded view of ancient days and ways.”[11]

These references to “camp” are intriguing, for of course they make one think about Susan Sontag’s “Notes on ‘Camp,’” which was first published less than a decade earlier in 1964. In her essay Sontag sought to identify, if not justify, camp as a phenomenon of taste and sensibility, not a critical idea. She noted that it was challenging to define camp intellectually, but that it was more appropriately experienced and performed. For Sontag, “Camp is a certain mode of aestheticism. It is one way of seeing the world as an aesthetic phenomenon[,] . . . a quality discoverable in objects and the behavior of persons.”[12] She directly associated camp with the decorative—“emphasizing texture, sensuous surface and style at the expense of content”—and proceeded to list examples of it from Gothic Revival interiors and Italian operas to Art Nouveau lamps and films by Cecil B. DeMille.[13] In the context of Alma-Tadema, it is particularly relevant that Sontag frequently listed examples of camp taken from High Victorian culture, including art by Aubrey Beardsley and Edward Burne-Jones and writings by Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde, individuals and works all associated with the Aesthetic Movement like Alma-Tadema.

Thinking about the exhibition at the Fries Museum in this context, it seems appropriate, then, to describe Alma-Tadema’s artwork even today as camp, not just in the scenes depicted or for their potential as decorative objects, but because of how viewers appreciate and interact with his paintings. Returning to Sontag in light of this, one discovers:

Camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature. It relishes, rather than judges, the little triumphs and awkward intensities of “character.” . . . Camp taste identifies with what it is enjoying. People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they labeled as “a Camp,” they’re enjoying it. Camp is a tender feeling.[14]

Thus, the cinematic influences of, and the performativity inherent in, Alma-Tadema’s paintings suggest that the viewer’s reception and participation in them makes them camp. This seems to have been the case over forty years ago at the Met Museum when Mellow described that exhibition as “camp” and certainly this seems to be the case in 2016 at the Fries Museum. Does this mean that Alma-Tadema as camp is bad art? Certainly not, for if we look again at Sontag’s essay, each person and cultural object she delimited as an example of camp is acknowledged today as a subject of serious scholarship. It is not the art that has changed, but our appreciation of it, and its increased popularity as a manifestation of our own culture.

While the concept of camp helps to explain the popularity of Alma-Tadema for the people who flocked to the exhibition, queued to closely examine each painting, and performed the actions seen therein, it would be short-sighted to assume that camp also explains Alma-Tadema’s talents as an artist. Indeed, it is interesting to note that even though Mellow in his 1973 review wrote disparagingly about Alma-Tadema, in fact he was complimentary towards his skills as an artist. He acknowledged the research Alma-Tadema did with regard to ancient artifacts as they appeared in his paintings and specifically lauded his “marvelous facility for painting furniture, draperies, jewelry, architectural details—his marble benches and mosaic floors are wonders.”[15] These acknowledgments are apt. Looking at a painting such as Unconscious Rivals, 1893, one can see the grandeur of the ornamental barrel vault ceiling, the shimmer of different tones in the marble column and walls, and the intricate sculptural details in the reliefs and figures in the round (fig. 6). Like his contemporary Leighton, Alma-Tadema excelled in painting drapery. The azaleas in this painting are exquisite as well, perhaps even too beautiful in their detail, but Alma-Tadema’s ability to depict flowers naturalistically in so many of his paintings is a testament to his attention to detail and likely associated with the “truth to nature” code to which the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood adhered and thus influenced others afterward.

Unconscious Rivals was one painting which I was eager to see in person, knowing it only in reproduction form beforehand. A detail from the painting also was on the cover of the English translation of the catalogue. On first encountering Unconscious Rivals in the exhibition, I admit I was disappointed to see that it was smaller than I had anticipated, a not uncommon experience based on first engagements through reproductions. Indeed, the diminished size seemed to contradict the grandiosity suggested by the monumental mural and the films in the exhibition. However, the more closely I examined the painting, the more I could see that it was a jewel of a picture with intricate details of elements like the azaleas making it an incredibly strong painting. The scene is of two young women who respond differently to an unseen man (represented by the legs and sword of an ancient statue of a seated gladiator, a sculpture then in the Borghese Collection) with whom each woman is in love, seemingly unbeknownst to the other. This narrative was part of the tradition of nineteenth-century genre painting, which audiences of the day appreciated and understood. However, while traditional genre painting offered a moral message, here the aesthetics take precedence and the depiction of the two women is more a statement about beauty rather than morality. The viewer (then and now) can identify with the women, sympathizing with the shy temperament of the brunette who gazes toward the picture plane with a sheepish smile, or responding sensually to the vivacious red-head (a Pre-Raphaelite trope of the femme fatale) flirting with the lover below the balcony. A reinterpretation of the allegorical sacred and profane that stretches backward to Titian and forward to Freud, Alma-Tadema’s Unconscious Rivals relies on a form of empathy that transcends time and nationalism, appealing to audiences to identify with these women emotionally, regardless if they or the viewer is ancient Roman, British Victorian, or twenty-first century Dutch or American.

As noted above, Alma-Tadema, klassieke verleiding opened and closed with rooms in which the artist’s works were presented with film clips demonstrating how his paintings influenced filmmakers of cinematic epics over the course of the twentieth century. In between these first and last rooms were a series of galleries arranged thematically around the artist and his work. The second section focused on Alma-Tadema’s early training, providing examples of artwork from his early years as a student in Antwerp at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and afterward. Seeing some of these early paintings was eye-opening in that the darker palette and Romantic medievalizing subjects contrast with the vibrant colors one associates with his classical themes later on.[16] Alma-Tadema worked for a time in the studio of the Belgian artist Henri Leys (1815–69), whose interest in accurate depictions of medieval and Renaissance history, painted in the style of artists of that time, led him to be appreciated by contemporaries such as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Even after Alma-Tadema left Leys’s studio, he continued to paint in a style similar to him, as is argued well by Jan Dirk Baetens in the catalogue.[17] Alma-Tadema’s painting Leaving Church in the Fifteenth Century, ca. 1864, demonstrates well this influence (fig. 7). The figures, exiting through a portal at Notre Dame de Paris, are depicted wearing an array of costumes from the early Renaissance, demonstrating Alma-Tadema’s talents in representing textures and fabrics and his close attention to historic detail. He reportedly took these figures from a fifteenth-century illuminated manuscript in the Royal Library at Brussels, research that would pay off for him over time as he continued to paint historicizing subjects utilizing illustrated publications and artifacts to guide him.

Archaeological objects in vitrines that also appear as objects in his paintings were part of the next section of the exhibition, which focused on his earliest classical subjects. The space was laid out with white, modernist interpretations of classical pilasters and walls painted candy apple red, potentially reminiscent of the color known in the nineteenth century as Pompeian red (fig. 8). This architectural setting worked well to showcase Alma-Tadema’s conversion to classicism, welcoming the viewer with a painting that is said to have been his first work in this style, Entrance of the Theatre, 1866 (fig. 9). Three years earlier, he had traveled to Italy for the first time on honeymoon with his first wife, and while there made numerous studies of what he saw. Entrance of the Theatre shows the exterior doorway of the Odeon, a comedy theater in Pompeii. A mother in a red toga holds her son’s hand and converses with the couple before them, while behind her a woman is assisted out of her carriage by a man. Examining the arrangement of the figures, one can understand the “Victorians in togas” critique; these characters could just as easily be wearing bustle skirts and top hats attending a performance at Covent Garden. What is more striking, however, is the way Alma-Tadema has captured a moment in time, as if the viewer, perhaps sitting in a carriage, has just turned his/her head and witnessed this greeting between the figures before them. Interested in temporality, Alma-Tadema wrote on the wall in the painting the cast list from the play these figures are about to see, The Girl from Andros by Terence (195/185–ca. 159 BCE). But the play is not contemporary to the individuals depicted, as the Flavian hairstyles of the women date the subject to somewhere from 69 to 96 CE, over two hundred years after the play would have been first performed. What makes this painting even more striking, then, is that it is a memento mori illustrating imagined individuals who would have been killed when Vesuvius erupted and destroyed Pompeii on August 24, 79 CE.

Alma-Tadema’s archaeological eye, then, dates from his early years when he used illuminated manuscripts and fashion histories to make Romantic-style paintings, then continued with firsthand observations when he traveled to Rome, Pompeii, and other areas in Italy.[18] In the next three galleries of the exhibition, the curators turned into archaeologists themselves, excavating and showcasing aspects of Alma-Tadema’s homes as creative spaces in which his family also participated, as his daughters Laurens and Anna and second wife Laura were painters too. After the death of his first wife, Alma-Tadema moved to London in 1870 with his children, fell in love, and married Laura Epps (1852–1909). The Alma-Tademas established two different households in London, the second (17 Grove End Road) more extravagant than the first (Townshend House near Regent’s Park). Alma-Tadema himself rose in the ranks of London society, exhibiting his classical paintings at numerous exhibitions and participating in the creation and dissemination of prints after his paintings, while decorating his homes and turning them into salons for artistic entertainment.

Because the decorative is such an important part of Alma-Tadema’s artistry, it is unfortunate that much of what was in his home has not survived or been identified; it would have been advantageous to see more extant examples of his furniture and interior designs. For example, Alma-Tadema designed an ornamental settee for the American financier and art collector Henry Marquand, which is now in the collection of the Met (fig. 10). Although it would have been inappropriate to include this in the current exhibition because it was made for someone other than Alma-Tadema, this settee demonstrates the artist’s interest in promoting taste and design associated with the Aesthetic Movement to others. Although there were only a few such objects in the exhibition, the first of the three galleries on Alma-Tadema’s home provided examples of how the family collectively participated in the creative process (fig. 11). Among these objects were a chair adorned with the intermingled initials of Lawrence and Laura Alma-Tadema and a six-panel folding screen painted by the husband and wife with domestic scenes of the Epps family, which was dramatically installed in the center of the gallery on a large platform. Before the screen, showcased in a vitrine, was a diptych of self-portraits by the couple painted after their marriage the summer of 1871 (fig. 12). Paired in a frame reminiscent of classical prototypes, the doors, when open, reveal painted on the inside of each a Dutch tulip and an English rose, signifying the couple’s respective nationalities.

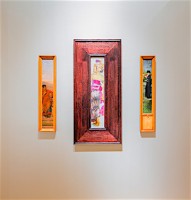

Among the surviving images that show off the elaborate decorative schemes of their homes, the most artistically noteworthy are the watercolors of Alma-Tadema’s second daughter Anna (1867–1943), whose works shimmer in their exquisite depiction of these interiors (fig. 13). Presenting rooms seen through doorways or as if glimpsed through keyholes, her skillful watercolors capture the dazzling effect that these ornate spaces may have had on visitors entering the Alma-Tadema family home for the first time. In the next gallery, the curators reunited a selection of the forty-five thin, vertical panel paintings that Alma-Tadema commissioned from his colleagues and friends, such as George Henry Boughton, Val Prinsep, and John Singer Sargent (fig. 14). Eventually these hung together in his so-called Hall of Panels at Grove End Road, showcasing them as the artistic calling cards of his artist-friends. Dispersed to other collections long ago, this was one of the first efforts to regroup many of these panels. At first this section was confusing in its arrangement, in part because the wall text was not immediately apparent, and because the frames for many of them now differ so they lack the cohesion they once had in his home. Nevertheless, they contributed well to demonstrating further the Aesthetic interior of the home and the family’s engagement with a large circle of artists.[19]

After the focus on the family and the home, the final gallery came almost as a breath of fresh air, not because the previous galleries or pictures were stilted, but because they told a much more personal story. In this last gallery were the masterpieces the viewer was waiting for, recalled from posters and digital images they had seen in the past, but now available for closer examination in person (fig. 15). This was one of the rooms where I witnessed most of the performative actions of the viewers as well. The pictures here were arranged on walls with the same modernist pilasters seen earlier, but now with ivory walls instead of red, and with the film clips projected over the paintings along the outer walls. This was the gallery in which one truly could appreciate the cinematic, performative, and archaeological aspects of Alma-Tadema’s work. With more space to walk around and examine the paintings from different angles, and in juxtaposition with one another, this was also the gallery where I discovered new ideas about Alma-Tadema’s artistry that I had not noticed before, specifically in his manipulation of visual space and composition.

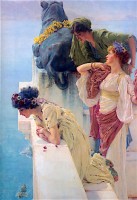

For instance, it has already been noted how his ability to paint marble, with its sheen and varied hues, was remarkable. One reason why Coign of Vantage, 1895, was used as the introductory wall mural and cover of the Dutch version of the catalogue was because of its remarkable verisimilitude in these details (fig. 16). What strikes the viewer upon seeing this painting in person, however, is how Alma-Tadema mastered optical effects. Gazing at the picture, the viewer stands on a precipice hovering over the women and the thick white vertical line of the marble balcony wall that together dominate the center of the picture plane. Perpendicular to this is the horizontal wall in the background and the torso and head of the women on the left who leans over the balcony to gaze downward at the incredibly sharp drop below toward the water. This dramatic scale in perspective, for the viewer and for the woman looking downward, is not unintentional, for they add incredible depth to a picture that (despite the implications of the mural) measures only 58.8 x 44.4 cm in size.

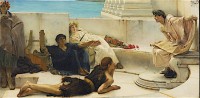

Alma-Tadema also is highly skilled with horizontal format compositions, reserved traditionally for landscape paintings and panoramas. His horizontally-oriented subjects are dramatically short in height, but have elongated lengths, so they differ greatly from large-scale history paintings that have used this format to tell narratives. In these unusual spaces, Alma-Tadema compresses entire groups of numerous figures into comfortable, naturalistic arrangements. In the most successful of these works, his figures are arranged not like a frieze but as a collective unit posed in curved spaces, ultimately creating a circular effect that unifies all the figures. A Reading from Homer, 1885, is an excellent example of this (fig. 17). The bodily engagement between the poet and his listeners starts with him as he reaches out physically and orally toward his listeners, moves along the bench and the woman reclining on it, wrapping around her companions and channeling back toward the poet through the man lying parallel to the bottom of the picture. This is visual poetry in the round.

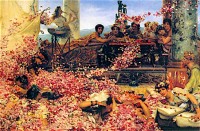

As the visitor headed toward the exit of the exhibition, one of the last works on display was The Finding of Moses, noted above as the record holder for Alma-Tadema’s paintings sold at auction (fig. 18). It was presented here with a scene from The Ten Commandments (1956) playing above it, showing the same scene of the Pharaoh’s daughter riding in a palanquin and discovering the child in the reeds. While this work clearly was meant to be the apex of the exhibition, emphasizing the cinematic and popular appeal of Alma-Tadema’s work, in fact a painting close by struck me as being even more important in Alma-Tadema’s oeuvre, not for its cinematic but its Aesthetic quality. This was The Roses of Heliogabalus, 1888, in which the young, decadent Roman emperor kills a number of his guests at a party by smothering them with rose petals (fig. 19). It seems an unlikely way to die, and this disbelief is revealed in the faces of the victims themselves who are unaware what is about to happen to them. The hues of red, pink, salmon, and lilac undulate like living creatures over them, recalling for the viewer Alma-Tadema’s skill in depicting flora, but making one more conscious of his importance as an artist associated with the Aesthetic Movement. Stepping away from the canvas, what one sees is an expressionistic swathe of color with a life force all its own. This affect of color is part of modernism, and helps tie components of the Aesthetic Movement with abstraction, Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, and Fauvism.

This color in Alma-Tadema’s paintings come through beautifully in every illustrated page of the catalogue published to accompany this exhibition.[20] The text is a welcome addition to the scholarship on Alma-Tadema, with a series of in-depth essays by a number of authors that help contextualize the artist’s work not just chronologically but also thematically and cross-culturally allowing for a broader appreciation of his art.[21] The “highlights” sections throughout the book offer brief, interesting tidbits as well, such as a section about his wife Laura and another on the artist’s interest in tactility. Ultimately, the catalogue and the exhibition successfully met its goal, which was to emphasize the impact of Alma-Tadema’s early years on his artistic training and career, to explore further the importance of his home-as-studio and the role his wife and daughters played in this, and to consider the afterlife of Alma-Tadema’s work as it influenced filmmakers through the twentieth century. Of these themes, the one likely to have the greatest impact on future scholarship will be the curators’ emphasis on the artistry of Alma-Tadema’s wife and daughters. Understudied and less well-known in comparison to other Victorian women artists such as Evelyn De Morgan, Emily Osborn, and Elizabeth Siddal, the catalogue in particular provides researchers with new information about their lives and work, and how they contributed to the artistic home and Aesthetic Movement for which Alma-Tadema himself was famous. Although the presentation of Alma-Tadema’s influence on epic filmmakers made for an engaging experience in the exhibition, I would argue that his paintings have more art historical value because of their own inherent cinematic and performative power directly on viewers, and not filtered through films. These “Victorians in togas” elicit meaning for the general public today because they are perceived to be a visual key to understanding the past, not as something remote and long gone, but as an extension of ourselves.

Roberto C. Ferrari

Curator of Art Properties, Columbia University

rcf2123[at]columbia.edu

[1] This exhibition was co-curated by Elizabeth Prettejohn, professor of history of art at the University of York, and Peter Trippi, independent art historian and currently president of the Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. My thanks to Marlies Stoter at the Fries Museum for providing us with tickets to see the exhibition, and to Peter Trippi for his assistance in obtaining the gallery views and many of the other images of art work that appear in this review.

[2] Edwin Becker, et al., eds., Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, exh. cat. (Zwolle: Waanders, 1996).

[3] “50,000th visitor for Alma-Tadema,” Fries Museum, Leeuwarden, available online: https://www.friesmuseum.nl/en/about-the-museum/news/50000th-visitor-for-alma-tadema/, accessed January 2, 2017. Assuming the momentum and popularity of the show continued through its run, an estimated 200,000 people visited the exhibition.

[4] The hammer price was $35,922,500, including buyer’s fee. This sale took place at Sotheby’s New York on November 4, 2010, and is currently the record for the highest amount ever paid at auction for a painting by an artist who dominated the second half of Queen Victoria’s reign (technically, the date makes it Edwardian, rather than Victorian).

[5] According to Alison Smith, lead curator of British Art to 1900 at Tate Britain, visitor attendance was 242,957 for the exhibition Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde, held at Tate Britain in London from September 12, 2012–January 13, 2013. Email to the author, January 4, 2017. The exhibition subsequently traveled to Washington, DC, and Moscow. Roberta Smith, in her review of the exhibition, referred to their art more than once as “kitsch” and panned it over and over with sentences such as “If you want a clear idea about what was rotten as opposed to enlightened about Victorian England, look no further.” Roberta Smith, “Blazing a Trail for Hypnotic Hyper-Realism: ‘Pre-Raphaelites’ at National Gallery of Art,” The New York Times, March 28, 2013, available online: http://nyti.ms/1EDhF1d, accessed January 7, 2017 (login required).

[6] In Quo Vadis? Blom notes that filmmaker Enrico Guazzoni referenced Alma-Tadema through mise-en-scène, such as location, costumes, props, space, and staging. In the case of Ridley Scott for Gladiator, Blom documents that the interiors of the Emperor’s palace and the furniture and accessories were taken from Alma-Tadema’s paintings. See Ivo Blom, “The Second Life of Alma-Tadema,” in Lawrence Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity, English ed., eds. Elizabeth Prettejohn and Peter Trippi (Munich: Prestel, 2016), 187–99, exhibition catalogue. Blom also notes that the paintings of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) were a source for these filmmakers. This cinematic approach to the French painter’s work has been documented elsewhere, including in the retrospective exhibition of his work held in 2010 at The J. Paul Getty Museum and elsewhere.

[7] It is worth noting that most of the viewers wore museum headphones and listened intently to the narrated tour, which they received by scanning QR codes with their devices. Thus, for those who reenacted the scenes in front of Alma-Tadema’s pictures, it was done almost as if in pantomime, arguably reinforcing the connections between the performative values of the paintings and the (silent-film) cinema.

[8] Christopher Forbes, Victorians in Togas: Paintings by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema from the Collection of Allen Fund (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973). About one-third of the paintings on view were actually from other collections to supplement Funt’s own Alma-Tadema paintings on display.

[9] Forbes, Victorians in Togas, 4.

[10] Allen Funt, “Foreword,” in Victorians in Togas, 2–3.

[11] James R. Mellow, “Alma-Tadema’s ‘Victorians in Togas,’” The New York Times, March 17, 1973, 27. Available online: ProQuest Historical Newspapers, accessed December 29, 2016.

[12] Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp’” (1964), in Susan Sontag: Essays of the 1960s and 70s, ed. David Rieff (New York: Library of America, 2013), 260.

[13] Ibid., 261.

[14] Ibid., 274.

[15] Mellow, 27.

[16] In contrast, one could argue that the darker palette of these early works had a strong influence on the tonality of some of his Egyptian subjects, such as The Death of the First-Born, 1872, which shows a scene from Exodus in which the Pharaoh holds in his arms the lifeless body of his eldest son killed in the last plague.

[17] Jan Dirk Baetens, “Alma-Tadema in Antwerp: The Legacy of Henri Leys,” in Alma-Tadema, 38–47. Exhibition catalogue.

[18] That said, one should not assume that Alma-Tadema can always be trusted with regard to archaeology. Ian Jenkins, in his highlights essay, reminds us that Alma-Tadema was first and foremost a painter and shows how he occasionally used artistic license. See Ian Jenkins, “An Informed Inventiveness,” in Alma-Tadema, 50–51. Exhibition catalogue.

[19] Charlotte Gere does not see Alma-Tadema’s homes as “Aesthetic,” because his color scheme was largely Pompeian red and ivory white and because Grove End Road had electricity and plumbing with hot and cold water. While a classical color scheme and modernist innovations may negate the strict definition of the Aesthetic interior, the elaborate art-centered space in which Alma-Tadema and his family flourished, in which guests arrived for salons, and in which musicians and singers gave performances, all clearly suggest that he was complicit in the principles of the Aesthetic Movement. See Charlotte Gere, “The Alma-Tademas’ Two Homes in London,” in Alma-Tadema, 91. Exhibition catalogue.

[20] Elizabeth Prettejohn and Peter Trippi, eds., Lawrence Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity, English ed., (Munich: Prestel, 2016). Exhibition catalogue.

[21] The introductory sections were written by Elizabeth Prettejohn. Essays and highlights were authored, alphabetically, by Jan Dirk Baetens, Eline van den Berg, Ivo Blom, Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, Carolyn Epps Dixon, Markus Fellinger, Alistair Grant, Charlotte Gere, Anne Helmreich, Ian Jenkins, Stephanie Moser, Elizabeth Prettejohn, Daniel Robbins, Wendy Sijnesael, Marlies Stoter, Peter Trippi, and Robert Verhoogt.