The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art

October 18, 2015–January 10, 2016

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis

February 17–May 27, 2016

The National Gallery, London

Catalogue:

Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art.

Patrick Noon and Christopher Riopelle.

London: National Gallery Company Limited, 2015. Distributed by Yale University Press.

272 pp.; 133 color illus.; bibliography; index.

ISBN: 978-1-85709-575-3

$60.

There are few artists who define an era quite as thoroughly as Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) did in early nineteenth century France. The scope of his work is impressive—from civic mural cycles to intimate lithographs and watercolors as well as the ‘grands machines’ painted for the annual Paris Salons. The number of his paintings that have come to exemplify the art of the Romantic period is astounding—Liberty Leading the People, The Barque of Dante, The Death of Sardanapalus, The Lion Hunt, The Women of Algiers in their Apartment and so many more. It was Delacroix’s spirit, however, that caught the attention of his contemporaries, who almost universally described him as the leader of the French Romantic movement regardless of whether or not they agreed with his aesthetic. He seemed to embody the qualities associated with Romanticism, not only in his work, but also in his life. Delacroix’s emotional intensity in experiencing the world and his commitment to recording those feelings in both written and visual forms epitomized the Romantic sensibility, and there is no question that his influence on future generations has been profound. Like many art historical presentations, this picture of Delacroix as THE Romantic painter has been repeated in countless introductory classes and coffee table books for decades, but it was not until recently that a clearly articulated exhibition presented an analysis of exactly how Delacroix and his work nurtured the growth of modernism. Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art, at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA) and the National Gallery, London, offered an opportunity to examine accepted interpretations closely, and most importantly, to study the work of both Delacroix and the subsequent generations of painters he influenced. As Gabriele Finaldi, director of the National Gallery, London, notes in the Foreword to the exhibition catalogue, “Despite Delacroix’s fame, the particular focus of Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art has not been the subject of a major exhibition or publication. Nor has any British institution hosted a serious Delacroix exhibition in fifty years—the last was the 1963 centennial exhibition in Edinburgh” (6).

Curator Patrick Noon, the Elizabeth MacMillan Chair of Paintings at the MIA, proposed the concept of this exhibition as a continuing development of the ideas presented in the 2003 show, Constable to Delacroix: British Art and the French Romantics, organized by the MIA and Tate Britain. The current exhibition focuses on Delacroix’s wide range of work and the enduring effect of his aesthetic explorations on several generations to come. As Noon describes it, the exhibition “. . . examines the radical role as mentor and archetype that Delacroix and his art played during his lifetime and subsequent decades, terminating in 1912 with Henri Matisse’s emulation of Delacroix’s voyage to Morocco eight decades earlier” (10).

The exhibition entrance at the MIA was a simple dark blue wall framing a large photographic reproduction of a detail from Lion Hunt (1861, Art Institute of Chicago) (fig. 1). The contrast between the tumultuous imagery of the lion hunt and the understated entryway effectively announced to viewers that they were about to enter a world of color, action, and emotional fervor. Once inside the exhibition space, visitors faced a large wall graphic illustrating the many painters influenced by Delacroix over time, as well as a reduced size reproduction of Henri Fantin-Latour’s painting Homage à Delacroix (1864, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) (fig. 2). The earliest sketches for Homage were created in the aftermath of Delacroix’s death on August 13, 1863, perhaps with the encouragement of the art critic and poet Charles Baudelaire who described Delacroix as “. . . above all, the painter of the soul in its golden hours.”[1] Like Baudelaire, Fantin-Latour was one of a small group of mourners who attended the painter’s funeral at Père Lachaise Cemetery and felt that Delacroix deserved considerably more recognition than he had received (37). Over the course of the next few months, Fantin-Latour worked and reworked the painting, ultimately creating an homage that expressed the importance of Delacroix to the next generation of artists and critics. Included in the group surrounding the enshrined central portrait of Delacroix are Edouard Manet, James McNeill Whistler, Alphonse Legros, Félix Bracquemond, and, of course, Fantin-Latour himself as well as the critics and theorists Baudelaire, Edmond Duranty, and Jules Champfleury. This image set the stage for exploring the significance of Delacroix’s influence that unfolded in the next five galleries.

The first gallery addressed the theme of emulation, first in the work of Delacroix who was himself an avid copyist of the old masters, and then in the work of numerous painters who paid tribute to him in their own work. At the center of the gallery—as in each succeeding gallery—was a painting by Delacroix on a stand-alone partition wall that served as a touchstone for the theme under consideration. In this gallery, that painting was Delacroix’s Self-Portrait (ca. 1850, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence), an image that epitomizes the enigmatic Romantic artist posed against a dark background (fig. 3). It offered a telling foil for the myriad paintings that mirrored Delacroix’s images, color or sensibility elsewhere in the gallery. The theme of emulation is presented on two didactic panels labeled “Emulation: Persona” and “Emulation: Copies and Interpretations”; both are truncated versions of the text in the exhibition catalogue that would have better informed the museum visitor if they had been reprinted in full.

This initial gallery swiftly established the range of Delacroix’s influence on future generations. Immediately to the right of the entrance were two large portraits, one by Delacroix of his friend and colleague Louis-Auguste Schwiter (1826, National Gallery, London) and the other by John Singer Sargent of a British aristocrat, Lord Ribblesdale (1902, National Gallery, London) (figs. 4, 5). Although separated by seventy-six years, the paintings validate the perennially stylish British dandy, albeit at different points in their lives. As Christopher Riopelle notes in his catalogue entry, “Sargent had a ready model for his portrait of aristocratic chic in Delacroix’s Louis-Auguste Schwiter, itself indebted to the art of Sir Thomas Lawrence and the long tradition of British portraiture that lay behind it. Indeed, Sargent may well have known the painting from visits to Edgar Degas, a passionate admirer of Delacroix, who had purchased it in June 1895” (74). This pairing of portraits not only established Delacroix’s love of British art and design, but also it demonstrated how his pervasive influence was transmitted through collecting as well as networks of artists.

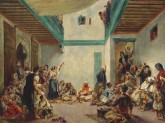

Behind the central wall with the Self-Portrait were paintings that involved direct copying from Delacroix’s paintings, often in unexpected ways (fig. 6). There was a remarkable copy of The Barque of Dante (1854, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon) created by a young Edouard Manet when he was studying in Thomas Couture’s atelier. Next to Manet’s Barque was Pierre Auguste Renoir’s copy of The Jewish Wedding in Morocco (ca. 1875, Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts), commissioned by the industrialist and Delacroix collector, Jean Dollfus (fig. 7). Although all of the Impressionists were fascinated with Delacroix’s technical virtuosity with color, Renoir was also deeply influenced by his curiosity about exotic locales and cultures. The Jewish Wedding in Morocco signals the beginning of an interest in North Africa that would lead Renoir to follow Delacroix’s path to Algeria in 1881. Also in this gallery were works by Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, and Odilon Redon that incorporated direct quotations from the paintings of Delacroix. Redon’s Pegasus and the Hydra (after 1900 Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo) was especially intriguing in its transformation of Delacroix’s 1851 ceiling mural in the Galerie d’Apollon, Musée du Louvre (fig. 8). In Redon’s hands, Pegasus becomes “. . . the Poet in his purity, his elevation, dominating Envy represented by a green and gold serpent that will coil at his feet but never reach him” (88).[2] Just as Apollo slayed Python, so too Pegasus confronted the Hydra, symbolizing the triumph of the Romantic artist over adversity and misunderstanding—at least in Redon’s interpretation.

Having established the overall scope of Delacroix’s influence on modernism, the next gallery addressed the theme of orientalism, shifting the wall color of the gallery from a cool sage green to a dramatic rusty red, visually and psychologically warming up the space in keeping with the North African subjects of the paintings (fig. 9). The first half of the orientalism sequence presented two overarching sources for Delacroix’s work: his visit to Algeria in 1832 and the poetry of George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788–1824). Immediately to the left as visitors entered the gallery was a theatrical canvas based on Byron’s heroic poem The Bride of Abydos, a Turkish Tale (1813) (fig. 10). Delacroix chose to depict one of the last scenes in the poem, a dramatic confrontation between the hero Selim and Pasha Giaffir just before the tragic shooting that will end all hope for Selim and his lover Zuleika. Although Byron’s poem may not be as familiar to audiences today as it was in Delacroix’s time, the painting Bride of Abydos (1857 Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas) still serves as a powerful statement of the artist’s mastery of color and emotional intensity. The viewer could get lost in contemplating the colors in the windswept clothing of Zuleika alone; how many shades of blue are there?; how many shades of lavender, pink and red?; are those highlights gold or white? It is easy to understand the allure of Delacroix’s colors, although much more challenging to grasp the sophistication of his technique. For his contemporaries, as well as later generations, color was almost always the starting point for an exploration of Delacroix’s work, and it was color that guided the viewer to the emotional content of the subjects.

Lord Byron’s poetry provided Delacroix with inspiration throughout his life, but none was quite so dramatic as the epic painting The Death of Sardanapalus (1827–28, Musée du Louvre, Paris), which was based on the poet’s 1821 play about an ancient Assyrian ruler (fig. 11). The smaller replica included in this exhibition was painted in 1846 when the original version was sold to the wealthy English collector, Daniel Wilson (fig. 12).[3] Like Bride of Abydos, both the original monumental painting and this later copy reveal Delacroix’s extraordinary technique in the use of glazes and interwoven strokes of color, but it is the conflict between this seductive visual extravagance and the horror of the subject matter that creates the emotional tension in these paintings.

Similarly, the strain between emotional content and visual allure informs the Convulsionists of Tangier (1838, MIA), a painting based on Delacroix’s direct experience of Sufi Muslims during his 1832 visit to Algeria (figs. 13, 14). The artist painted eighteen watercolors of this trip immediately after returning to Paris in July of 1832, but it was not until six years later that he completed the painting (112). Here, the drama was neither imagined nor based on Byron’s creative endeavors, but rather a depiction of an actual event that Delacroix experienced during his stay in Tangier. The annual Sufi pilgrimage to the funerary monument of Sidi Mohammed Ben Aïssa typically involved unforgettable physical contortions along the road, which the artist tried to capture on his canvas. The poet and art critic Théophile Gautier commented on this phenomena twenty-three years later in 1855: “If I had not seen for myself the Aïssaouas indulging in their strange exercises . . . we would probably accuse the Convulsionists of Tangier of exaggeration. Nothing could be truer [than]. . . this furious torrent of Aïssaouas, writhing in their convulsion of sacred epilepsy . . . hideously demented, followed only by a few guardsmen who protect their frenzy” (112).[4]

Immediately to the right of the Convulsionists of Tangier was Renoir’s Arab Festival (1881, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), also a painting based on the artist’s experience on site in Algeria (see fig. 13). Although not a depiction of spiritual ecstasy, Arab Festival has a similar sense of energy and frenetic movement as the dancing figures twist and turn through the landscape. Like Delacroix, Renoir framed his composition with the simple architectural planes of white-washed buildings that visually contain the exuberant energy of the figures, but here the painter has pushed the boundaries of his work nearly into abstraction decades ahead of Wassily Kandinsky’s experiments in 1911.

The gallery contained a variety of other orientalist paintings as well, most often shown adjacent to an example of Delacroix’s work. For example, Théodore Chassériau’s Battle of Arab Horseman around a Standard (1854, Dallas Museum of Art) was paired with Delacroix’s later depiction, Arabs Skirmishing in the Mountain (1863, National Gallery, Washington, DC) (figs. 15, 16, 17). A comparison between these works highlights the younger artist’s reliance on more traditional compositional strategies as well as his emotional distance from the subject. He has learned much about color from Delacroix, but his figures retain the sculptural quality more characteristic of neoclassical painters or even renaissance Florentines.

Two other paintings in this gallery must be mentioned simply because they are remarkable examples of Delacroix’s work. Both are based not on his experience of North Africa, but on his memories (fig. 18). In the terms established by the exhibition curators, these are “re-imagined” images, a combination of fact and dreams recollected in later years. View of Tangier from the Shore (1858, MIA) exemplifies this process of “re-imagining,” which enabled this later, more introspective form of orientalism. The sources for the image seem to have come from two separate, but related experiences in Delacroix’s life; first, his actual landing in Tangier in a large dinghy in 1832, and second, sketches of cliffs at Fécamp in Normandy from the 1840s (fig. 19) (131). As Noon notes in his catalogue entry, it has also been suggested that an incident in which the artist helped sailors bring a fishing boat ashore in Normandy in 1849 may also have been the initial inspiration for the subject (131). A similar approach is evident in Women of Algiers in their Apartment (1847–49, Musée Fabre, Montpelier), a re-working of the original 1834 version of the subject. Fifteen years after completing the first painting, Delacroix revised his composition as a dream-like imagined space. Noon comments that it is now “. . . an evocative atmospheric interior stripped of superfluous details and exuding a lethargic reverie characteristic of the fantasized orient of many contemporary writers, especially Charles Baudelaire” (132).

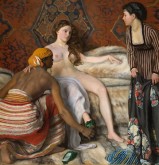

The theme of the orient as a re-imagined place provided the focus of the second half of this gallery, with examples of work from Cézanne, Narcisse-Virgile Diaz de la Peña, Chassériau, and Eugène Fromentin as well as Delacroix. Two paintings from 1870, one by Renoir and one by Frédéric Bazille, demonstrated a fresh interpretation of orientalist visual language more in keeping with Baudelaire’s concept of the painter of modern life (fig. 20). Renoir’s portrait of Madame Clémentine Valensi Stora (L’Algérienne) (1870, Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco) not only displays a taste for orientalism, but also hints at the background and personality of the nineteen-year-old Clémentine Valensi Stora; her richly detailed brocade garment reflects her Algerian birthplace as well as her heritage as a member of a prominent Sephardic Jewish family (fig. 21). In addition, her husband Nathan Stora was an art dealer in Paris who specialized in North African antiquities, and who undoubtedly carried similarly luxurious fabrics and clothing in his shop (134). This portrait thus becomes not simply an exotically beautiful young woman, but a meaningful statement about how Clémentine and Nathan Stora perceived their role in contemporary Parisian life.

Bazille’s painting La Toilette (1870, Musée Fabre, Montpelier, France) takes orientalism even further into the realm of everyday life, albeit with an exotic twist (fig. 22). The Islamic patterned wallpaper sets the stage for a beautiful nude woman reclining on a fur-covered divan attended by a woman in African dress and a presumably Parisian maidservant who, it must be noted, is holding a Japanese style kimono. In spite of its orientalist references and Bazille’s familiarity with Delacroix’s work, La Toilette makes no attempt to suggest that this is anything other than a Parisian interior. It is not a dream of faraway places, but a contemporary rendering of a very modern fantasy.

The rather cramped second gallery opened onto the more effectively designed third gallery, which was dedicated to the theme of “narrative painting at a crossroads” (fig. 23). The centerpiece Delacroix image, directly in the viewer’s line of sight when entering, was The Lamentation (1848, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) (fig. 24). The power of this image was immediate. Baudelaire’s commentary on the artist’s religious work seems almost to be describing this painting in particular: “The imagination of Delacroix! Never has it flinched before the arduous peaks of religion! . . . On his inspired canvases he pours blood, light and darkness in turn” (152).[5]

In the context of the theme of narrative painting, The Lamentation extended an invitation to consider the nature of visual storytelling and how it can be most effectively developed. Unfortunately, the didactic panels in this gallery did not even begin to address this theme in any meaningful way. The museum’s apparent policy of watering down ideas for a public that is believed to be incapable of understanding anything more sophisticated than a sound byte has here done a disservice to both viewers and the art. The exhibition catalogue on which this text was based offers a thoughtfully developed essay on narrative art, on the relationship between “imitating” and “imagining,” and on Delacroix’s position that religious subjects allowed “. . . full play to the imagination so that each person finds in them his own particular feelings to express” (151).[6] It would have been much wiser to embrace this content for the benefit of viewers who were interested in engaging in the question of “narrative painting at a crossroads” rather than displaying a text that is out of context and confusing.

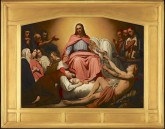

An alternative approach to narrative painting was offered diagonally across from The Lamentation where Ary Scheffer’s Christus Consolator (1851, MIA) was on display (fig. 25). Although Delacroix and Scheffer were lifelong friends, their approach to narrative religious painting could not be more different (fig. 26). The impeccably smooth finish, the renaissance tripartite composition, and the frozen stillness of the figures must have been anathema to Delacroix; the cool formal detachment of Scheffer’s figures invites little response from the viewer other than courteous approbation. In spite of this, Scheffer’s image became a celebrated symbol for the Abolitionist movement in the United States because of the figure of a shackled African slave among those in need of consolation.

Elsewhere in the gallery was van Gogh’s large canvas of the Pietà (after Delacroix) (1889, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam), which he based on a black-and-white print of the Delacroix painting (fig. 27). Not having seen the original artwork, van Gogh’s interpretation was a study in blue and yellow; describing his process in a January 1890 letter to his brother Théo, he wrote that his copy work consisted of “. . . translating into another language, the one of colors, the impressions of chiaroscuro and white and black” (172).[7] Van Gogh’s pietà iconography contains the emotional intensity that is characteristic of Delacroix, but re-imagined in an entirely new formal language.

Odilon Redon also engaged in reinterpretations of Delacroix’s narrative imagery, creating numerous paintings of boats on the open sea, usually steered by various Christian figures (170). Positioned between Delacroix’s Sea of Galilee (1853, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps’s Job and his Friends (ca. 1853, MIA), Redon’s small painting takes advantage of the accepted trope of the boat as a vessel of salvation (fig. 28). The sailors in the Red Barque (ca. 1895, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) are unidentifiable, however, and the brilliant red vessel has neither sails nor oars. The radiant sun engulfs the craft in an energetic aura, suggesting perhaps that the luminous Christ from Delacroix’s Sea of Galilee has been transformed into pure light (fig. 29).

In a small viewing space adjacent to the third gallery, a short film about Delacroix’s mural projects ran continuously throughout the day. Museums often include videos about special exhibitions, but they are rarely as beautifully filmed and as elegantly presented as this one. Curator Patrick Noon and a Minneapolis film crew were granted access to the Parisian spaces where Delacroix’s most important murals are located, and spent several weeks shooting on site. The result is Delacroix’s Murals, a 14-minute film featuring grand ceiling paintings in the Salon du Roi and the libraries of the Deputies’ Chamber at the Palais Bourbon and the Peers’ Chamber at the Luxembourg Palace (1838–47); and the Galerie d’Apollon at the Musée du Louvre (1848–51). The famous wall decorations at the Chapelle des Saints-Anges at the Church of Saint-Sulpice (1849–61) are included as well. The public accessibility of the murals at the Musée du Louvre and the Church of Saint-Sulpice facilitated Delacroix’s influence on future generations of artists, offering a source of inspiration to anyone who chose to look. Viewers were able to share that experience through the film, enjoying close-up shots of the resplendent Deputies’ Library ceiling or the sunlit drama of Heliodorus Driven from the Temple at the Chapelle des Anges. In addition, Noon’s commentary paralleled the imagery with a description of the trajectory of the artist’s career and reputation. Short of traveling to Paris, this was the best possible way to learn about the role of Delacroix’s murals in the larger context of his work and legacy.

The final two galleries of the exhibition were devoted to the issue of Delacroix’s significance to the development of modern art (fig. 30). That his impact on modernism was both seminal and inspirational was solidly established in the first three galleries, but the curators chose to define his enduring legacy from the dual perspective of “prose” and “paint” (203). Noon’s introductory essay to this section of the catalogue focuses on Delacroix’s written work, noting the impact of his published articles on art history and aesthetics during his lifetime, as well as the effect of his posthumously produced journals in 1893 (203). As in the previous gallery, the informational panel came up short (fig. 31). It is paraphrased from Noon’s charming introduction to a longer catalogue essay on the theme of Delacroix’s legacy, but it cannot have been intended as an explanation for the conceptual framework of this gallery.

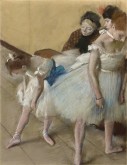

The artwork in this space was equally divided between paintings that related to literary narratives and landscape canvases, some of which also referenced written sources. In Ovid in Exile Among the Scythians (1859, National Gallery, London), for example, Delacroix referenced the story of the Roman poet Ovid, exiled for unspecified reasons by Caesar Augustus and left to die among the Scythians (fig. 32). Delacroix may have seen himself in Ovid, or perhaps he was thinking of Baudelaire, who had been charged with obscenity only two years earlier for the publication of Les Fleurs du Mal (194). Other paintings have a more tenuous connection to the written word, but nonetheless reflect the crucial importance of Delacroix to the formation of modernism. Edgar Degas’s The Dance Examination (ca. 1880 Denver Art Museum) is one example of this (fig. 33). The Impressionist admired Delacroix’s work early in his career, but then became fascinated with the neoclassical emphasis on drawing exemplified by the paintings of J. A. D. Ingres; it was not until Degas turned to the use of pastel in the 1880s that his study of Delacroix’s technique again became crucial. Throughout his career, however, he continued to collect prints, watercolors and paintings—as well as 190 drawings—by Delacroix (210).

In the other half of the gallery were landscape paintings by Bazille, Claude Monet, Cézanne, Paul Signac, and Jean Metzinger (fig. 34). Delacroix’s contribution to this group was a small oil painting of Champrosay where he rented a house (247). The extraordinary popularity of these small landscape paintings, sketches and watercolors, many of which were sold at the 1864 studio sale after Delacroix’s death, made them particularly influential on the emerging modernist visual language. Landscape at Champrosay (1850s, Private Collection) for one, was purchased by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Delacroix’s friend and one of the mentors to the new generation of artists arriving in Paris in the 1860s. Among that generation, many painters also owned work by Delacroix: Degas owned an oil sketch of a landscape at Champrosay as well as his large collection of drawings, prints, and paintings; Monet owned two small watercolors of landscapes from Etretat and Dieppe; and Cézanne owned a larger watercolor of a bouquet of flowers (247–248).[8] Van Gogh, who had little money for purchasing original art, nonetheless owned prints of Delacroix’s work that were provided by his brother Théo (172). Later, the generation that came of age in the 1880s would find inspiration in Delacroix’s newly published journals. Signac’s painting in this gallery, Snow, Boulevard de Clichy (1886, MIA), reminds the viewer that the Neo-Impressionist artist titled his 1899 treatise D’Eugène Delacroix au Neo-Impressionisme, indicating both his high regard for Delacroix’s work and his belief that the leading Romantic artist in France was a formative influence on the late nineteenth-century avant-garde (fig. 35).

The study of Delacroix’s legacy that began with the investigation of his “legacy in prose” continued in the last gallery of the exhibition with a study of his “legacy in paint” (fig. 36). Here the wall color changes to a warm vanilla reminiscent of the now iconic “white walls” found in the modernist galleries of the twentieth century. The central focus remains a Delacroix painting, in this case Basket of Fruit in a Flower Garden (1848–49, Philadelphia Museum of Art), an extravagant display of fruits and flowers that might be described as pure painterly expression (fig. 37). There is no concern for storytelling here, only delight in the act of painting. On either side, the modernist generations are well represented with a selection of flower still-lifes by Courbet, Bazille, Redon, van Gogh, and Gauguin to the right, and studies in color by Henri Matisse and Wassily Kandinsky to the left (figs. 38, 39, 40). The point could not be clearer: as Cézanne famously remarked “We all paint in Delacroix’s language.”

As the twentieth century unfolded, Delacroix’s influence appeared in the early work of Matisse, initially as the theoretical approach advocated by Signac, but eventually as an independent statement of decorative patterning in his Fauves paintings. In The Red Carpet (1906, Musée de Grenoble), Matisse embraced the legacy of Delacroix in the colors and patterns of intensely designed textiles as objects of interest in their own right, but he also began to glimpse a future that would radically shift the spatial hierarchies based on the past. Likewise, the growing abstraction visible in Kandinsky’s early twentieth-century work spoke to the importance of Delacroix’s influence while simultaneously leaving narrative behind entirely (fig. 41). Christopher Riopelle summed it up in his catalogue entry on Study for Improvisation V (1910, MIA): “The Romantic experiment initiated with Delacroix’s first appearance at the Paris Salon of 1822, The Barque of Dante, achieved spiritual resolution in works such as Kandinsky’s Study for Improvisation V some ninety years later, with its evocation of a spiritual realm created in paint which could not be fully interpreted, merely experienced at the deepest level of body and soul” (254).

The objective and scope of this exhibition was well defined as an examination of “the radical role as mentor and archetype that Delacroix and his art played during his lifetime and subsequent decades terminating in 1912 with Henri Matisse’s emulation of Delacroix’s voyage to Morocco eight decades earlier” (10). By establishing an endpoint for the period covered by Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art, the curators acknowledged that the emergence of abstraction and new formal aesthetic concerns would take modernism in a direction less likely to be influenced by Delacroix. It must be noted, though, that the perception of Delacroix as the archetypal artist has had a longer reach well into the twentieth century and perhaps the twenty-first century as well. For better or worse, the Romantic notion of the suffering artist who is misunderstood by society has become embedded in western society, and Delacroix seems to have been the first visible example of that trope. An exploration of this phenomenon, and Delacroix’s contribution to the creation of this nexus of ideas, would be very welcome. Next exhibition perhaps?

Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art offered a thoughtful presentation not only on the role of Delacroix as an example of the Romantic artist, but also on the specific ways in which his technical innovations were copied and re-interpreted over time. The wealth of documentation in the exhibition catalogue about Delacroix’s professional life, including commissions, sales, and publications, is extremely useful for anyone seriously interested in studying the artist. Most important though is the examination of the enduring significance of Delacroix’s ideas for modern artists whose styles are far removed from the Romanticism of the first half of the nineteenth century.

Janet Whitmore

jwhitmore12[at]gmail.com

[1] Charles Baudelaire, “The Salon of 1859” in Baudelaire, Art in Paris, 1845-1862, edited by Jonathan Mayne (London and New York: Phaidon Press Limited, 1970), 171.

[2] The original source for this quotation comes from Odilon Redon’s memoirs, À Soi-Même, Notes sur la vie, l’art et lest artistes (Paris: H. Fleury, 1922), 20.

[3] The Musée du Louvre acquired The Death of Sardanapalus in 1921 as part of the bequest of Maurice Audéoud. The large size of the painting (3.92 m x 4.96 m) generally prohibits it from traveling to any other venue.

[4] The original source for this quotation comes from Théophile Gautier, Les Beaux-Arts en Europe-1855, 2 volumes (Paris, Lévy, 1855), 181.

[5] Baudelaire, “The Salon of 1859,” 166.

[6] Eugène Delacroix, Correspondence générale d’Eugéne Delacroix, edited by André Joubin, volume 3 (Paris, Plon, 1935), 37.

[7] Vincent van Gogh: The Letters, edited by Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten and Nienke Bakker (Amsterdam and The Hague: Huygens Instituut, 2009), letter 839 (dated January 13, 1890). See also http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let839/letter.html.

[8] Delacroix’s watercolor landscapes owned by Monet were The Needle at Etretat and Cliffs near Dieppe. Both hung in Monet’s bedroom at Giverny and are today in the collection of the Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris. See Adrien Goetz, Monet à Giverny (Paris and Giverny: Fondation Claude Monet, 2015), 40.