The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Été 14: Les derniers jours de l’ancien monde

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, François-Mitterand site, Gallery 2, Paris

March 25–August 3, 2014

Catalogue:

Été 14: Les derniers jours de l’ancien monde.

Edited by Frédéric Manfrin and Laurent Veyssière.

Paris: Seuil-Volumen, in association with the Bibliothèque nationale de France and the Ministère de la Défense DMPA, 2014.

279 pp., 250 illus. (color and b&w); bibliography; index.

€39

ISBN: 978-2-7177-2564-3

Été 14: Les derniers jours de l’ancien monde is the result of the collaborative effort of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and the Ministère de la Défense in commemoration of the centenary of the start of the First World War. In addition to materials loaned by each of these two organizations, the exhibit received a variety of contributions—including letters, newspapers, books, photographs, objects, film clips, and paintings—from over thirty lenders. In the preface to the exhibition catalogue, Bruce Racine, president of the Bibliothèque Nationale, notes that the goal of Été 14 was to show the “complex thread of diplomatic, political, and military events” that pushed Europe into the furnace of total war (n.p.). Similarly, Minister of Defense Jean-Yves Le Drian writes that the exhibit aimed to highlight the complexity and ambiguity of the days leading up to the war’s outbreak (n.p.).

Upon entering the exhibit, the viewer encounters a grainy video clip of the funeral cortege for Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife. This section functions as a foreword to Été 14, as it is visually and thematically separate from the remainder of the exhibition space (fig. 1). The assassination, which occurred in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, was the catalyst that led to the outbreak of war in the summer of 1914. This gallery serves as an effective preface because the remainder of the exhibit fills in the story, so to speak, as it details the prominent characteristics of European society, culture, and politics both before and after this watershed event.

Été 14 is composed of seven core thematic sections that radiate outward around a curved picture rail, much like the spokes of a wheel. This central rail keeps the viewer linked to the moves that pushed the continent into conflict via a chronology of the crucial decisions and key events that occurred between July 23—the day on which Austria issued its ultimatum to Serbia—and Great Britain’s August 4 declaration of war on Germany, which marked the final step toward war (fig. 2). The viewer moves counterclockwise around the thematic galleries that surround this central rail. In doing so, he gains an understanding of how the changes taking place throughout Europe in the years and days prior to the First World War contributed much to how diplomatic decisions were made and the way in which events unfolded from late July to early August. Reflecting the crescendo of tension during this time, a selection of correspondence is affixed to the rail, showing reactions of politicians and military officials to the critical developments of these twelve days.

Along the perimeter wall of the exhibition, the viewer encounters images of ten recognizable figures in science and literature—Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, and Joseph Conrad, for instance—coupled with their reactions to the crisis of 1914, which range from anxious concern to a willingness to assist to indifference (fig. 3). This selection of opinions serves as a reminder of the complex spectrum of emotions and responses fostered by the possibilities and actualities of the First World War. In tandem with the central rail of the exhibit, this peripheral wall forcefully guides the viewer’s path. Once he has zigzagged between galleries, observing the various items on display, it seems unnatural to visit the previous sections of the exhibition.

The introduction of the exhibition, “Intro: Un été comme les autres,” highlights the generally pleasant, carefree mood across prewar Europe. While video clips show popular recreational activities such as fishing and biking, posters advertise railroad travel, current events—the Exposition internationale in Lyon opened in May, for example—and women’s fashion for the summer season (fig. 4). Also, three paintings each present a key element of European society in the decades leading up to the First World War: the continued existence of sizable agrarian populations, the growth of industrialization, and the carefree, opulent lifestyle typically associated with the Belle Époque (fig. 5). Finally, lighthearted music fills this section, offering the listener an auditory summary of the era’s mood.

Next, the viewer enters the gallery titled “Le monde d’hier, l’Europe de 1914,” the first of the seven thematic sections of Été 14 (fig. 6). The goal of this room is to familiarize the viewer with the power structure of Europe on the eve of the war. In addition to displaying portraits and photographs of the various European heads of state, this gallery demonstrates that royal blood linked many rulers across the continent. For example, German emperor William II and his cousin George V of Great Britain chat while on horseback in a 1913 photograph of a parade in Potsdam. International relations appear cordial and Europe remains pacified for the moment, but socio-political tensions are increasing both within and between individual states. Various styles of government with differing political agendas are found across the continent. Furthermore, the burden of ruling over a vast, multi-ethnic population begins to weigh on certain nations, as evidenced by a satirical map of Austria-Hungary intended to highlight the empire’s ethnic hodgepodge. While Europe as a whole seems to be the unrivaled seat of power in the prewar world, there is a clear gap between the robust economies in the northwest—Great Britain, Germany, France, and, to a lesser extent, Belgium, and the Netherlands—and those of nation-states in the southern and eastern areas of the continent (fig. 7).

The following gallery, “L’Europe au coeur des échanges,” presents the viewer with a panorama of an increasingly interconnected prewar Europe. Nations are linked to one another through an array of exchanges and interactions across all realms of modern life, including economics, politics, culture, and science. Advertisements for steamship travel, posters trumpeting the Olympics, photographs of scientific and intellectual congresses, and images of colonial industries all attest to the heterogeneity of European societies at the time as well as to the multifarious bonds that joined nations and connected individuals (fig. 8).

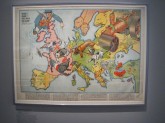

“La guerre à l’horizon?” is the third of the seven thematic displays. As the title of this section implies, people around the continent were well aware of the fragility of a European peace precariously maintained via a system of alliances. A caricature that appeared in Le Grelot on October 8, 1893, encapsulates the tense political climate. This image shows Europe, an elderly woman with a distressed expression, gripping a flower basket that holds two soldiers—representative of the Franco-Russian alliance—in her right hand and a birdcage containing outward-facing cannons and the distorted figures of Italy, Germany, and Austria-Hungary—indicative of the Triple Alliance—in her left hand. The woman’s face, resembling the dial of a barometer, has its hand pointing upward to “peace,” but it seems that the hand could easily shift left or right to “war.” Elsewhere in this gallery, a map of Europe depicts the prominent powers as different breeds of dogs aggressively gesturing and barking at one another, and an advertisement for the anti-German daily Le Revanche shows French and Russian soldiers working together to slay a German octopus that is attempting to stretch its tentacles across Europe (figs. 9, 10). To highlight the importance of nationalism and the alliance system, this section also displays pedagogical games and toys for teaching French children about the “good” and “bad” nations in Europe (fig. 11). Other images depict conflicts and territorial struggles on the periphery of Europe and further abroad. Photographs such as those capturing the fighting in the Balkans in the few years just prior to the First World War suggest that tensions between European states were felt beyond the borders of a given nation.

The viewer next moves into “Pacifismes/bellicismes.” In this gallery, animated endorsements of war are juxtaposed with equally impassioned calls for maintaining peace or, at the very least, not provoking a Europe-wide conflict. A variety of books, newspapers, and images espouse the different perspectives, capturing the viewpoints of socialists, communist-anarchists, and Christians as well as ardent nationalists and advocates of the purifying properties of battle (fig. 12). Other items on display include a photograph of French Socialist leader Jean Jaurès and a caricature showing Jaurès and anti-Semitic, saber-rattling politician Joseph Lasies, each attempting to coax the French Republic, depicted as Marianne, to support his agenda (fig. 13). The overall impression is that Europeans were not unanimous regarding the desire for war—or for peace—in the years leading up to the First World War, and, much like Marianne in the caricature, they faced impassioned pleas both from pacifists and those with a more belligerent platform.

“Tu seras soldat!” focuses on the romantic view of warfare in a Europe that had not witnessed a major conflict since the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71. In the decades following that confrontation, the growth of nationalism fueled the valorization of military life, and the result was a distorted opinion about the nature of a future conflict. An array of subject matter is presented to demonstrate how the rise in nationalism and the romantic view of the soldierly life was disseminated throughout European society. Books, posters, and paintings glorifying the military are displayed alongside printed material and games for children that were intended to reinforce national pride and aggrandize warfare (figs. 14, 15).

“Préparer la guerre” presents a shift in the type of item on display in Été 14. In addition to an assortment of books, maps, and archival material discussing different war tactics, this gallery exhibits First World War era rifles from Great Britain, Germany, France, Russia, and Italy. A set of printed handkerchiefs that were issued to soldiers by their respective militaries is also displayed. These rectangular cloths contain numerous images and a variety of information, including instructions for disassembling one’s weapon, data on the characteristics of each branch of a nation’s ground forces, and details regarding how to care for the wounded (fig. 16).

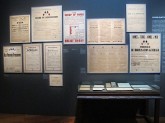

The periodic ringing of an unseen bell, perhaps calling soldiers to the fight, serves as an overlay for the final of the seven thematic galleries, “Mobilisations.” Requisition and mobilization posters from France, Germany, Great Britain, and Austria-Hungary are shown opposite a case housing infantry uniforms from each belligerent nation (figs. 17, 18). Appropriately mounted alongside these placards is a selection of photographs of crowds reacting to the calls to arms. These images convey the sense of astonishment tempered with firm resolve that Europeans likely felt as the possibility of a Europe-wide conflict became a reality. This gallery also has a hands-on element that brings the viewer closer to the war experience in 1914: wearable reproductions of the French military’s wool kepi and the German army’s spiked leather helmet are displayed in front of the vitrines housing the uniforms (fig. 19).

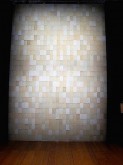

The conclusion of the exhibition, “Le choc,” brings the reality of the war to the forefront and is perhaps the most arresting gallery of Été 14. After encountering the clattering sound of machine gun fire and a display of automatic weapons, the viewer is presented with evidence of the physical and psychological damage suffered both on the battlefield and the home front in the late summer of 1914. A primary goal of this portion is to highlight the extent to which the brutal actualities of the First World War were a violent divergence from previous romantic notions of battle. Posters with jingoistic proclamations intended to rally war support on the home front are shown alongside pictures exposing the atrocities—supposed or real—committed by the enemy (fig. 20). Photographs of dead and wounded soldiers and images of refugees and the rubble of bombed cities capture the seemingly indiscriminate horrors of the conflict (figs. 21, 22). A lithograph by Jean Veber, one of the most disquieting images in this gallery, encapsulates the shock experienced by many soldiers in the opening days and weeks of the war (fig. 23). This picture, which also serves as the background of the exposition catalog, shows a group of French soldiers, some with injuries, moving around in a dazed manner in the wake of a battle; the only coloring on this black-and-white drawing is the red that covers the petrified face and upper chest of the soldier in the foreground of the image. As the viewer walks around this gallery toward the exit, he/she is faced with a backlit rectangular block on the wall. Standing out in this darkened display space, this block is composed of 1008 individual notifications that inform loved ones that a French soldier died in battle; the magnitude of the slaughter of the First World War is emphasized by the fact that these deaths represent just a portion of the twenty-seven thousand men killed on August 22, 1914, the bloodiest day single day of the war for France (fig. 24).

Été 14: Les derniers jours de l’ancien monde offers the viewer a comprehensive presentation of how Belle Époque Europe was plunged into a global conflict that permanently altered the continent. Moreover, with regard to the type and origin of items on display and the various societal and political topics analyzed, the exhibit is both balanced and thorough. Lastly, Été 14 convincingly demonstrates that no one, not even the most vocal saber-rattling nationalists, could grasp the extent to which the First World War would traumatize and drastically change the Europe that existed up until the late summer of 1914. Most assuredly, the conflict was a shock for all Europeans. The stark visual contrast separating the somber, dark atmosphere of the concluding section from the halcyon, bright ambiance of the introduction of Été 14 reiterates this point; the nearness in space between the two sections suggests the degree to which Europe was altered drastically in a relatively short interval of time. This assertion is further highlighted through the clever employment of sounds at the beginning and the end of the exhibit. Surrounded by the sounds of warfare that fill the last galleries, the viewer can still make out the faint melody of a pleasant Belle Époque song. The soft music serves as a reminder of the chronological proximity of the Europe that existed before the First World War even as this Europe was being shattered by the conflict.

Gregory C. Seltzer

Graduate Student

University of Kentucky

gregory.seltzer[at]uky.edu