The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Impressions of Interiors: Gilded Age Paintings by Walter Gay

Frick Art Museum, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

October 6, 2012 – January 6, 2013

Flagler Museum, Palm Beach, Florida

January 29 – April 21, 2013

Catalogue:

Impressions of Interiors: Gilded Age Paintings by Walter Gay.

Isabel L. Taube, with contributions by Priscilla Vail Caldwell, Nina Gray, Sarah J. Hall and Emilia S. Boehm.

London: D. Giles Limited, 2012.

224 pp.; 104 color illus; 24 b/w illus; selected bibliography; index; chronology.

ISBN:978-1-907804-08-3

$55 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-0-615-57374-8

$34.95 (softcover)

The recent exhibition, Impressions of Interiors: Gilded Age Paintings by Walter Gay, at the Frick Art Museum in Pittsburgh offers a glimpse of wealthy expatriate Americans living in France and the carefully designed interior spaces of their homes at the turn of the twentieth century. It is a rare opportunity to study the early roots of American interior design as an independent creative practice, as well as the work of Walter Gay (1856–1937), an academically trained painter who specialized in capturing the interior spaces of both his own homes and those of his friends and family. According to Frick Art Museum director, Bill Bodine, the concept for this exhibition first occurred in 2006 at the opening of another show Possessions, Personalities and the Pursuit of Refinement, which focused on the Frick family members’ collections; during that event, Bodine found himself expressing admiration for Walter Gay’s three paintings of the Frick family’s New York mansion (2). Research subsequently revealed that Gay’s work had not been systematically examined since 1980 when it was the subject of a retrospective at the Grey Art Gallery and Study Center at New York University. Eventually, the Frick Art Museum proposed the development of a monographic exhibition of Gay’s work under the direction of guest-curator Isabel Taube, an art historian with special expertise in the role of interior design imagery in American painting (fig. 1).[1]

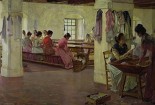

Although the core of this exhibition is Walter Gay’s paintings of gilded age interiors, the viewer is first introduced to his work as a naturalist painter in 1880s Paris. Somewhat ironically, these early paintings of working class artisans and peasants are on display in a grand gallery with green velvet wall-coverings, massive crystal chandeliers and a lustrous parquet floor (fig. 2). Gay’s career began with his training in the studio of Léon Bonnat (1833–1922) in 1877. Living and working in Montmartre during these years, he would have been aware of the myriad new directions in painting, including both impressionism and naturalism. His own paintings from the mid-1880s reveal a preference for quiet scenes of working women, such as The Weavers (1885, private collection) or Novembre, Etaples (1885, Smithsonian American Art Museum), as well as anecdotal history scenes (fig. 3). He made a successful debut at the Salon of 1879 and went on to win medals not only in Paris, but also in Munich, Antwerp, Berlin, Budapest, and Vienna (8). This kind of painting garnered considerable attention from the art-viewing public as well as private galleries and the French government. For example, one of Gay’s last major naturalist paintings, The Cigar Makers of Seville (n.d., Musée Goya, Castres, France) was purchased by the state in 1894, and immediately became part of the Luxembourg Museum collection of contemporary art (fig. 4).[2]

By the mid-1890s, however, Gay made a marked shift in his subject matter, choosing to focus exclusively on painting interior spaces devoid of people. As Taube explains in her catalogue essay, “Walter Gay’s Poetic Rooms,” this “alteration in the subject of his work was less a break and more of a shift in emphasis: he removed the human drama, making the backdrop itself the central focus” (35). In part, this reorientation of focus may also have been a result of Gay’s marriage in 1889 to Matilda Travers, a New York heiress whom he met in 1887 in Paris. Ms. Travers’s inheritance during that same year ensured that she and her future husband could enjoy a comfortable life together.

The first gallery introduces the newlyweds’ affluent life in the paintings of Magnanville, the country manor house that they began renting in the 1890s. It was here that Gay first began painting interior spaces in earnest. One early example, unfortunately not available for reproduction, is an elegant watercolor, Dining Room, Magnanville (ca.1895, private collection), a tonal study in shades of white and brown with an emphasis on the play of light as the viewer looks into a sunny dining room from a shadier hall. What is striking about this piece is that it reveals a delight in the geometry of space that will later be subsumed by a more poetic approach to interior imagery.

As Gay refined his thinking about interior paintings, he increasingly emphasized what he called the “spirit of empty rooms” (36).[3] Curator Taube elucidates this development in terms of Gay’s growing tendency to depict interiors as he personally interpreted them: “His use of the term “spirit” suggests that he sought to convey the characteristic atmosphere or essential nature of a room rather than its actuality, allowing for its transformation into art. He sought to accomplish this aim by rendering his impressions of the spaces in a personal manner with visible brushwork and carefully constructed compositions rather than trying to depict them in an accurate, objective way” (36). This strategy becomes more evident in the paintings of Gay’s next country rental property, the Château de Fortoiseau near Fontainebleau Forest, although it was also here that he painted a rare double portrait of Matilda, reclining on the sofa, and himself as a reflection in the mirror behind her (fig. 5).

Filling out the large first gallery is a selection of furniture that belonged to the Frick family, most of which is in keeping with the eighteenth-century interior design styles favored by Walter Gay in his own homes (fig. 6). Of particular relevance to the exhibition is the library table displaying photographs, memoirs and Gay’s palette as well as his 1894 Legion of Honor medal (fig. 7). This gallery also provides an overview of the Château du Bréau, where the Gays settled in 1906. A grouping of small paintings on the wall opposite the entrance depicts two exterior views of the château flanked by views of the exterior environment as seen through windows and doors, all somewhat atypical in Gay’s later work (fig. 8). The purchase of the Château du Bréau, located just outside of Paris near Fontainebleau Forest, included 500 acres of property, as well as archives dating from 1710 that recorded the history of the building and the site. It provided an ideal setting for Walter and Matilda Gay to establish their poetic vision of interior design based primarily on the rococo style of Louis XV.

The paintings of the Château du Bréau interiors provide a focal point for much of his work. His repetition of motifs from slightly different perspectives, and with multiple variations in the placement of objects and furniture, underscores his intention to investigate the creation of the poetic interior. These are not documentary paintings, nor are they design renderings for a potential patron; rather, they are musings on how the placement of objects, furniture, fabrics, and boiserie elements can change the feeling or mood of interior environments, and how subtle changes can evoke a shift in the aesthetic response to the room. The main salon at Bréau was a favorite subject for Gay’s design explorations. The architecture and the eighteenth-century commode remain constant in images of this large room, but almost everything else is modified continually. In La Commode (after 1906, private collection, Brooklyn) for example, Gay offers a glimpse of a sunny corner of the salon with a tightly grouped composition of furnishings flanking an elaborately draped full-height window (fig. 9). An unassuming rococo side chair stands beneath an ormolu wall clock while the commode on the adjacent wall hosts an impressive collection of blue and white porcelain bathed in light. Gay has created an intimate corner, full of sunshine and visually alluring objects. In contrast, The Commode (The Yellow Chair) (1905-12, Art Institute of Chicago), repeats the motif of Louis XV chairs, now upholstered in what appears to be watered silk, and showcases the commode against an interior wall, surmounted by a mirror set into the rococo boiserie (fig. 10). This time, candlesticks on either side of a bronze sculpture demand attention on top of the commode while the mirror on the wall above reflects a window on the opposite side of the room. Looking more closely, the mirror reveals an image of the drapery on the window seen in La Commode, as well as the ormolu clock, which has been relocated so that it too appears here.

Without a grasp of the context in which Walter Gay was working, this repetition of design motifs might seem tedious, or even overly focused on the display of his personal material wealth. In this exhibition, the catalogue is critical to rounding out the viewer’s understanding of both the painter’s goals and his role within a group of Americans who sought to create more sophisticated domestic interiors. Taube’s essay sets the stage for exploring Gay’s perception of his aesthetic role, and also provides welcome background on the role of the images of interior spaces in nineteenth-century painting. In a succinct overview, she traces the history of “interior views” from private souvenirs commemorating particular events or memories early in the century to more commercial production of albums featuring watercolors of rooms in royal palaces. These types of images were, in essence, portraits of rooms, a new concept that gave legitimacy to the depiction of a designed space as a form of creative work. Later in the century, images of interior environments became vehicles for transmitting a particular aesthetic viewpoint; the Japoniste interiors of James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), for example, not only evoke a mood of exoticism and luxury, but also provide a clear picture of how to place porcelain vases in front of a mirror or hang a collection of fans on the wall. Likewise, his design of the Peacock Room for Frederick R. Leyland’s London home exemplifies the emerging role of the artist as a design consultant for interior spaces.[4] Walter Gay’s paintings make a similar argument, albeit for an eighteenth-century, rococo aesthetic rather than the exotic Japonisme of Whistler and his cohorts.

As Taube notes in her discussion of Gay’s role as a tastemaker, “the interior served as a means to express his particular tastes while advancing an ideal of dwelling for others to follow” (45). Like many others who rejected the cluttered interiors of much nineteenth-century design, Gay argued for a coherent stylistic approach. Although his paintings demonstrate the effects of changing the scale, proportion or placement of furnishings, and suggest decorative options for the viewer to consider, it is his advocacy of a unified design vocabulary that sets Gay apart. Like his friends Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman, Gay believed that there should be a “single historical style throughout the house” that reflected an individual’s sensibility while remaining within the parameters of harmonious design (52).[5] For Gay, that harmony arose from creating a sense of comfort, elegance and beauty in domestic interiors.

Further background on the roots of interior design as a professional discipline are covered in Nina Gray’s essay, “Gracious Living: The Interior Decoration of Walter Gay and His Circle.” The work of Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman is covered in greater detail here, and Gay’s friendship with Elsie de Wolfe is discussed at length (67–73). Unlike the others, de Wolfe worked regularly as a practicing interior designer, defining a standard of taste in the United States that has survived to varying degrees until the present. Like the Gays, her aesthetic preference was eighteenth-century design, advocating “simplicity, suitability and proportion as the guidelines for the decoration of interiors” (70). She, too, owned a home in France that became a design “laboratory and showroom for her professional role as a decorator” (73). And it was Elsie de Wolfe who decorated many of the interiors at Henry Clay Frick’s Fifth Avenue mansion in New York in the years before World War I.

A decade later, in 1926, Helen Clay Frick (1888–1984) commissioned Walter Gay to paint three interior spaces at her parent’s home. The first of the three paintings was the famous Fragonard Room (ca. 1926, Frick Art and Historical Center, Pittsburgh), filled with Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s monumental series of paintings, The Progress of Love, 1771–72, whichHenry Clay Frick had acquired in 1915 (fig. 11). Sarah J. Hall notes in her brief essay on these three paintings that “Gay’s painting not only references the glory of Fragonard’s masterpiece, but also, by freezing the particular arrangement of those panels in the Frick’s residence, it celebrates their installation within the Frick mansion” (26). Two years later, Gay was also commissioned to paint the Boucher Room, which was then Adelaide Frick’s boudoir, decorated by Elsie de Wolfe (fig. 12). In his usual fashion, Gay eliminated some the furniture as he painted the image. The last of the three paintings for the Frick family was The Living Hall, also from 1928(fig. 13). Like the Boucher Room, this is a simplified vision of a very detailed ornamental space. Gay has emphasized not only comfort in the cozy seating around the crackling hearth, but also Frick’s financial and cultural power as displayed by the Hans Holbein and El Greco paintings that dominate the scene. It should also be noted that Gay’s brushwork becomes increasingly impressionistic in these late works as he creates his poetic interpretations of interior spaces.

The catalogue concludes with a comprehensive discussion of each of the 69 paintings and watercolors in the exhibition. Organized both chronologically and geographically, it allows the reader to absorb each image and contemplate the context in which they were created. This attention to detailed analysis is all too rare in the twenty-first century museum catalogues; perhaps this will be a harbinger of changes to come.

Walter Gay’s position in the context of American painting of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century is somewhat elusive. Although he shared many ideas with modernist design reformers who advocated for a unified interior design vocabulary, he did not embrace the contemporary styles of his era, preferring instead to adapt a rococo aesthetic to modern life. Similarly, although he rejected naturalism in the 1890s, his painting became increasingly modern, both in his expressionistic brushwork and in his insistence on creating compositions that evoked a mood or emotion in the viewer. Most important, as Taube notes, he invited “an active observer to imaginatively enter and dwell in [his paintings]” (60).

Janet L. Whitmore

Harrington College of Design

JWhitmore[at]harrington.edu

[1] See Isabel L. Taube, “Rooms of Memory: The Artful Interior in American Painting, 1880 to 1920” (Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2004).

[2] The Cigar Markers of Seville is undated, but the provenance records currently at the Musée d'Orsay state that it was exhibited at the Salon de la Société des Artistes Français in 1894, from which it was purchased by the state. This was the typical process used by the French government to acquire paintings for its contemporary art collection, then housed at the Luxembourg Palace. Today, the painting has been transferred to the Musée Goya in the city of Castres in southern France.

[3] This is the phrase that Gay used in his memoirs. See Walter Gay, Memoirs of Walter Gay (New York: privately printed, 1930), 60.

[4] Many of Whistler’s paintings highlight the importance of interior design in creating a sophisticated aesthetic environment. For a fuller discussion, please see Ellen E. Roberts, “Japanism and the American Aesthetic Interior, 1867–1892: Case Studies by James McNeill Whistler, Louis Comfort Tiffany, Stanford White, and Frank Lloyd Wright” (Ph.D. diss., Boston University, 2010). For a first-hand perspective on Whistler’s work on the interior design of the Peacock room, see The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler at University of Glasgow: http://www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk The key correspondence between Whistler and Leyland occurred between April 1876 and June 1877. For a short summary of this controversial project, and images of the room, please see the website of Freer Gallery of Art which the Peacock Room is on display, at: http://www.asia.si.edu/exhibitions/online/peacock/6.htm

[5] Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman, Jr., were pioneers in establishing interior design as an independent creative field. Their book on the subject was a seminal publication for anyone concerned with interior furnishing. See Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman, Jr., The Decoration of Houses (London: B.T. Batsford, 1898).