The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Hammershøi and Europe

Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Curators, Kasper Monrad and Annette Rosenvold Hvidt

February 4–May 20, 2012

Hammershøi and Europe: A Danish Artist Around 1900

Kunsthalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung, Munich

Curator, Roger Diederen

June 15–September 16, 2012

Catalogue:

Hammershøi and Europe / Hammershøi und Europa / Hammershøi og Europa.

Kasper Monrad, with contributions by MaryAnne Stevens, Anne Hemkendreis, Peter Nørgaard Larsen, Annette Rosenvold Hvidt, Tone Bonnén.

Munich: Prestel, 2012.

255 pp.; 192 color illustrations; list of exhibited works; bibliography

ISBN:

978-3-7913-5174-2 (English trade edition)

978-3-7913-5191-9 (German trade edition)

978-8-7920-2356-8 (Danish trade edition)

€39.95 ($49.95; £35; 324 kr.)

Hammershøi and Europe opened in June 2012 at the Kunsthalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung in Munich, the second and final venue for the large retrospective (fig. 1). Kasper Monrad, senior research curator at the Statens Museum for Kunst (National Gallery of Denmark), conceived this impressive show and catalogue to place the Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi within various international artistic currents of his time (fig. 2). Assembling more than eighty of his works, as well as some forty paintings by contemporaries, the exhibition ran from February until late May 2012 in Copenhagen, where Hammershøi was born in 1864.[1] The curator for Munich was Roger Diederen, who would assume the director’s post at the Kunsthalle on January 1, 2013. Diederen’s task for the Hammershøi exhibition was to introduce his audience in Munich to a painter well known in Denmark, but hardly a household name in Germany. Six paintings in his show, however, had been lent by German museums.

As Patricia G. Berman pointed out in her splendid recent survey of nineteenth-century Danish art: "Of all the painters working in Denmark at the turn of the last century, Vilhelm Hammershøi was one of the most internationally celebrated."[2] Hammershøi had impressed not only English, French, and Italian critics and collectors around 1900, but attracted Rainer Maria Rilke and other German writers and art dealers. Encouraged by the French critic Théodore Duret, who admired his work in Copenhagen in July 1890, Hammershøi exhibited in Munich for the first time in 1891. He sent seven paintings to the Glaspalast for the annual exhibition of the art of all nations, winning a medal for his contribution.[3] He also participated the following year in the international exhibition at the Glaspalast.[4] One painting shown in 1892 may have returned to Munich for the 2012 exhibition: An Old Woman (1886, The Hirschsprung Collection, Copenhagen). The painting also appeared in 1899 as a full-page illustration in the Berlin journal Pan.[5] After 1892, Hammershøi sent no more paintings to Munich until 1909. When he won a first class medal that year, the art historian Georg Biermann praised the artist as a "modern Nordic Vermeer." Curator Diederen put the phrase to good use in publicity for Hammershøi and Europe [.pdf].[6]

Earlier German enthusiasm for the Danish painter faded after he died in 1916. His international reputation began to revive in the 1980s following the exhibition Northern Light, circulated by Kirk Varnedoe to three American museums and to Gothenburg, Sweden.[7] In 1997–98 a monographic exhibition launched at Ordrupgaard in Copenhagen traveled to the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.[8] The Gothenburg Art Museum and the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm mounted a retrospective in 1999–2000. Then, a decade ago, Felix Krämer organized the first German retrospective at the Hamburger Kunsthalle.[9] He described the exhibition catalogue as the first publication in German devoted to the artist, although a dissertation and list of works by Susanne Meyer-Abich was available in a microfiche edition.[10] In 2008 Krämer was co-curator with Naoki Sato of an exhibition evocatively subtitled "The Poetry of Silence." After a run at the Royal Academy in London, the show traveled to the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo.[11] Krämer became director of the nineteenth-century and modern collection at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt in 2008; in October 2012, he could announce the acquisition of the Städel’s first Hammershøi.[12] Prices for the painter’s works on the art market rose steadily in the twenty-first century, and on June 11, 2012 – the same week the Kunsthalle show opened in Munich – a painting sold in London for nearly $2.7 million, establishing a record for any Danish work of art sold at auction.[13]

However alluring the canvases might be, the artist had to be delicately re-packaged for Munich. Passage from the bustling pedestrian street into the Kunsthalle’s upstairs galleries called for some preparatory information to smooth entry into the artist’s poetic, but oddly pared-down and decidedly private world. In the foyer of the Kunsthalle, maps accustomed visitors to Danish place and street names, and a chronology offered an outline biography (fig. 3). Diederen, working with the exhibition designer Matthias Kammermeier, created a cohesive narrative path for an artist notably reluctant to tell stories in his pictures. The nine rooms of the show drew Hammershøi works into tentative dialogues with parallel efforts by other artists; the chosen interlocutors were those the Danish painter may have seen exhibited in Copenhagen or noticed during his European travels. Hammershøi avidly visited exhibitions and galleries in Paris, London, the Low Countries, Italy, and Germany.

Entering the first room ("Introduction"), many viewers immediately approached a male portrait on the opposite wall, guessing correctly that it was the diffident Hammershøi himself. Self-portrait was painted in 1891, the year of his marriage to Ida Ilsted and immediate departure for what would be a six-month honeymoon in Paris. To the left of that self-portrait hung the portrait of the artist’s sister, Anna, his first exhibited work (fig. 4). When the picture, shown at the Royal Academy’s annual spring exhibition in Charlottenborg in 1885, failed to win the academy’s Neuhausen prize, Hammershøi’s former colleagues collected signatures to complain. P. S. Krøyer, his teacher at the Frie Studieskoler (Free Study Schools), an alternative private art school, urged the art critic Karl Madsen to lead the protest.[14]

In his substantial catalogue essay for Hammershøi and Europa ("Intense Absence," 13–143), Kasper Monrad notes that the portrait of Anna "ushered into Danish art the Symbolist and anti-Naturalist currents of the period to come," even if Hammershøi did not become a pure Symbolist himself (54). Monrad offers an incisive comparison to Henri Fantin-Latour’s portrait of his sister Marie, hanging in Munich in the adjacent room. The writer is careful to note that Hammershøi had not yet seen an original painting by the French artist when he painted Anna; the parallels, Monrad remarks, "are not due to influence, but to similarity of intentions" (54). This approach to understanding the importance to Hammershøi of depicting a human being "isolated in her own world," as Monrad says of Anna, is typical of the intuitive reach of comparative material throughout the exhibition.

The initial room in Munich offered the essence of Hammershøi, apparent even in the earliest canvases. The airy hanging also invited reveries of time travel; more than a century earlier Munich exhibition visitors had been among the first outside Denmark to see some of these works, less happily wedged into a room with other Danish art at the Glaspalast. Felix Krämer is sure that the portrait of Anna was no. 560 in the 1891 exhibition; Poul Vad, however, citing the same catalogue number, identifies it as the artist’s magisterial Portrait of Ida Ilsted (hanging next to Anna in 2012).[15] According to Vad, the lovely portrait of Hammershøi’s fiancée, sister of his former Academy friend Peter Ilsted, was sent directly from Munich to the Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris; the dealer attempted to sell it to Duret, but the shy artist—even more reticent in French—made only the lamest attempts to market it.[16] More important, perhaps, for Danish art than the European trajectory of Portrait of Ida Ilsted was its earlier impact in Copenhagen in March 1891 at Den frie Udstilling (The Free Exhibition). This first show of the independent, jury-free exhibition society took place at the gallery of art dealer Valdemar Kleis. Hammershøi, Johann Rohde, and Jens Ferdinand Willumsen were among the founders of the Danish secessionist group.[17]

The hanging in the introductory room of the exhibition included several more views of Ida Hammershøi (fig. 5). Getting to know Ida—and Ida’s face—was vital here. She was the central figure in her husband’s work, but in subsequent rooms of the show he would depict her most often from the back. In Two Figures, painted during the couple’s stay in London in 1898, the artist’s back, remarkably, dominates the picture. A studio photograph tentatively dated from the same year shows the Hammershøi couple full face; posing with them is the young Henry Madsen, suggesting his close bond with the childless pair.[18] In a later painting on this wall, Ida Hammershøi with a Teacup (1907, Statens Museum for Kunst), the artist depicted his wife after serious surgery; she would survive her husband by thirty-three years.

In Munich, striking international comparisons began on the entry walls of the first room. Examples of similar intentions, pointed out by Kasper Monrad in his essay, included a Eugène Carrière canvas from the Tate Gallery: Winding Wool: The Artist’s Wife and Daughter (1887), a foil to Hammershøi’s Evening in the Drawing Room (1891). Monrad used the pair as a double-spread illustration in the catalogue (58–59).[19] Even the small, delightful Hammershøi farmscapes from 1883, lent by Günther Fielmann from the Schierensee Manor collection, found a parallel vision in Fernand Khnopff’s In Fosset, Rain (1890, The Hearn Family Trust, New York). The comparisons continued in the second room ("Spotlight on Women") with a painting by Ida Hammershøi’s brother Peter Ilsted (fig. 6).[20] On this first long wall of the second room was a series of Hammershøi images showing lone women engaged in household tasks, completed by his earliest back view: Anna Hammershøi (1884, private collection, London).

On the adjacent short wall, two works by Fantin-Latour flanked Hammershøi’s Three Young Women, painted in 1895 (fig. 7). Monrad writes in his essay that each of the women in Hammershøi’s trio "can be seen as a transformation of Whistler’s mother" (fig. 8). Awaiting the Munich exhibition visitor in a later room was, in fact, James McNeill Whistler’s Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1, Portrait of the Painter’s Mother, lent by the Musée d’Orsay for both venues of the show. When Hammershøi arrived in Paris during the autumn of 1891for his second and final visit, he would have seen for the first time the famous Whistler work, purchased earlier that year by the French government for the Musée du Luxembourg. In the catalogue Monrad also traces inspiration from Paul Gauguin’s Woman with a Flower (1891, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen) in the central depiction of Ida Hammershøi in Three Young Women(63, 52).[21] He reminds the reader of his essay that some of Gauguin’s new Tahitian paintings were shown in Copenhagen at Den Frie Udstilling in 1893.[22]

Another Whistler anchored the second long wall of the section "Spotlight on Women": Arrangement in Yellow and Grey: Effie Deans (ca. 1876–78, Rijksmuseum, on deposit at Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam). Whistler’s model Maud Franklin, posing as Effie, brought a bracing whiff of narrative into a room lined with serene domestic interiors. His picture—cunningly described by the painter as an "arrangement" —recalled the clamorous events of the Walter Scott novel (The Heart of Midlothian, 1818) and those of Whistler’s dramatic life, so unlike that of the Danish painter who abstained from telling stories. William Nicholson’s Lady in Yellow and two Khnopff portraits—Portrait of Marie Monnom (1887) and Posthumous Portrait of Marguerite Landuyt (1896)—aptly represented Whistler’s widespread influence. In a stunning sequence on the fourth wall, the Danish painter’s indispensable rear view of Ida from 1905, Young Lady, Resting, was set in the context of an impressive work from the same year by Anna Ancher, Interior with Red Poppies and a similar painting by Hammershøi’s close friend Carl Holsøe. The early Matisse Woman Reading (1895, Centre Pompidou, on loan to the Musée departmental Matisse, Le Cateau-Cambrésis) rounded out this thoughtful and instructive hanging.

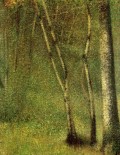

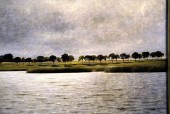

That the painter moved outdoors in the third room of the exhibition—"Disenchanted Nature"— came as a respite after dozens of interiors (fig. 9). Although Hammershøi and his wife enjoyed walking, he did not stray as far from his apartment as one might expect in a Nordic painter. According to Monrad, Hammershøi favored suburban parks and settled farmland, scrupulously purging his motifs of any inhabitants. He was not the only artist of his time to seek emptiness. The array of landscapes began with two sublime views painted in the moor near Worpswede, by Hans am Ende and Fritz Overbeck. A fascinating catalogue essay by Anne Hemkendreis explores Rainer Maria Rilke’s enthusiasm for Hammershøi, originating during the poet’s stays in the Worpswede artists' colony.[23] There Rilke developed his concepts of landscape; he spoke, for example, of the space between tree trunks as more glorious than the trees themselves, a perception he applied to Rodin sculptures (174). Hemkenkreis concludes that Rilke may have abandoned his intended article on Hammershøi when he realized that the Dane’s practice as a painter was incompatible with his own views. She remarks that the spaces between tree trunks and branches in his works are lifeless, particularly obvious in Landscape in Snow, Søndermarken (1895–96, The Hirschsprung Collection).[24] In his essay Monrad compares Hammershøi’s "strong focus on the tree trunks in the foreground" of the snow landscape to an early Georges Seurat, The Forest at Pontaubert (fig. 10). In Near Fortunen, Jægersborg Deer Park North of Copenhagen (singled out by Monrad as unique in Hammershøi’s art), the trees, seen from below and backlit by the sun, melt into both the sky and their own shadows on the ground (134–37).[25] This unusual painting demonstrates that Hammershøi was interested in outdoor sunlight, as well as in the effects of occasional sun within his rooms. The striking View of Gentofte Lake, Sunshower (1903, private collection), another landscape on view in Munich, confirmed his fascination with sunlight filtered by clouds (fig. 11).

Only nine paintings hung in the fourth room, a small, chapel-like space entitled "The Portrait." At the apse end was Whistler’s portrait of his mother, the first appearance in Germany of the world-famous canvas (fig. 12). For the few viewers who did not move straight to the Whistler, a series of elderly women on the long wall opposite the entrance marked the way (fig. 13). In two of them Hammershøi depicted his own mother; he painted both pictures before 1891, that is, before he saw the Whistler original in Paris. In the earlier of the two, a portrait from 1886, the artist nevertheless revealed his awareness of Whistler’s composition by reversing it. The later picture is less a Whistlerian arrangement than a traditional genre scene: Interior, with the Artist’s Mother (1889, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm). Between the two hung An Old Woman, also from 1886, the canvas illustrated in the journal Pan in 1899. The composition and pose may carry a faint echo of Whistler, but Monrad introduces it simply as an example of a genre picture "without any genre content" in the initial section of his catalogue essay, subtitled "Stories that are not told" (14). Danish painter Anna Ancher often depicted her mother, who ran the famous Brøndums Hotel in Skagen. Monrad writes in the catalogue that when Ancher painted the portrait of her mother chosen for the show, she too "undoubtedly knew Whistler’s painting, but she neither adopted his painterly devices not wished to quote directly from it" (64–67). Ancher’s Sunshine in the Blind Woman’s Room (1885, The Hirschsprung Collection, Copenhagen) and The Artist’s Mother (ca. 1877, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie) by the German artist Louis Eysen completed the series of seated elderly women.

For her comprehensive catalogue essay on "Hammershøi and England," MaryAnne Stevens mined archives—chiefly of The Hirschsprung Collection—to understand why the artist visited that country more often than any other. She describes his six trips to England, beginning with the winter of 1897–98 and the last in 1913. Stevens looked beyond the standard chronology to trace Hammershøi’s motives and his social and artistic contacts. She concluded that Alfred Bramsen, his anglophile collector in Copenhagen, played a major role in arousing the painter’s eagerness to travel to England (149). Bramsen had commissioned family portraits, including one of Bramsen’s son, Henry—The Cello Player (1893)—and had requested another of his daughter, Karen, completed in 1898.[26] The painter was also determined to meet his idol Whistler, who, to his chagrin, remained in Paris during that first London stay in 1897–98.[27] By the time Hammershøi returned to London in 1905, the American master was dead. Of particular value in Stevens’s essay is her reconstruction of the collection of the concert pianist Leonard Borwick, who befriended and supported Hammershøi in England (156). When the Hammershøi couple visited Borwick at his Elizabethan farmhouse in Sussex, the pianist introduced him to the painter Edward Stott, who lived nearby; Stott’s Starlight: Landscape (undated; Towner Gallery, Eastbourne) was a brilliant selection for the Munich exhibition (151). In her essay, Stevens substantially refines the inherited view of Hammershøi’s social skills; he studied English, moved in widening circles of acquaintances, and paid visits. He did not, however, journey to England during 1907, the year that his contacts resulted in a one-man show immediately following his critical success at the exhibition of Danish art at the Guildhall Art Gallery in April–May (156). Stevens closes her remarks on the artist in England with a trenchant paragraph on the critical response to "modern interior painting," which accepted Matisse and Hammershøi as equally valid modernists.

Two group portraits of families, one by Eugène Carrière and the other by Hammershøi, closed the small portrait section of the show (fig. 14). Carrière’s painting resembles an oversize sepia photograph lit by a strong flash. Hammershøi illuminates the faces of his wife and a young friend, leaving his brother and another friend in shadow. The peculiar Evening in the Drawing Room is an unfinished variation on Five Portraits (1901–02, The Thielska Gallery, Stockholm), the equally haunting and improbably large painting—more than six by nine feet—that Hammershøi considered his most important work; it was unfortunately not shown in Munich. In both pictures, several figures sit at a rectangular table laid with one of Ida’s impeccably ironed tablecloths. In the smaller canvas, the tablecloth catches most of the light, reflected on the faces of Ida and Henry Madsen seated on the far side of the table; Svend Hammershøi sits on the right end.

The man in the foreground in Evening in the Drawing Room is Thorvald Bindesbøll, architect, designer, ceramicist, and long-time friend of both the brothers. In the Stockholm painting, the normally ebullient architect sits at the left end of the table, with Hammershøi’s painter friend from his student days Carl Holsøe at the right end; Holsøe’s propped-up feet extend into the foreground, where Svend Hammershøi smokes a pipe. At the center of the table are Karl Madsen and J. F. Willumsen, who, with Johan Rohde and Vilhelm Hammershøi, founded Den Frie Udstilling; in 1893 the group opened its own exhibition building, designed by Bindesbøll. Willumsen, architect of the group’s second exhibition hall, is the focus of Five Portraits. Hammershøi painted the large picture immediately after Willumsen returned from the United States in the autumn of 1901; the painting was shown at Den Frie Udstilling in March 1902. The two group portraits represent Hammershøi’s surprising contribution to the genre of artists' gatherings so common toward the end of the last century. A more somber and wintry contrast to Krøyer’s Hip, Hip, Hurrah! (1888, Gothenburg art Museum) can scarcely be imagined; Monrad relates Five Portraits to Fantin-Latour’s Corner of the Table (72-74).[28] Disappointed that the Statens Museum for Kunst did not acquire Five Portraits and that the colossal picture would go to Stockholm for the new gallery of the banker Ernest Thiel, Hammershøi abandoned work on Evening in the Drawing Room, his last group portrait.

Entering the fifth room of the exhibition ("This modern Nordic Vermeer"), the visitor arrived in familiar Hammershøi terrain: the interior with a figure (figs. 15 and 16). In a catalogue essay, Peter Nørgaard Larsen, head of collections and research at the Statens Museum for Kunst, proposes homelessness as a fruitful concept for understanding the Danish artist. He suggests that for Hammershøi "the art of painting—especially when applied to interiors—became the special place where he could define and create a seemingly . . . safe base" (186). Invoking Walter Benjamin’s description of the interior as "the private citizen’s universe," Larsen sees the Hammershøi interior "as a carefully delineated and controlled domain that he can stage and shape to act as a place of sanctuary and, perhaps, as a kind of fortification capable of holding the outside world at bay" (191).

After the Hammershøis returned from England in 1898, they rented an apartment at Strandgade 30, in a seventeenth-century district of Copenhagen. They were able to keep the apartment until 1909, and its architecture shaped the content of the artist’s work for more than a decade. An essay ("Living inside the Painting") by Annette Rosenvold Hvidt, art educator at the Statens Museum for Kunst, focuses on comparisons with intimist contemporaries, particularly Knopff and Pierre Bonnard (197–218). In his essay Monrad points out that Hammershøi wrote from Paris to Johan Rohde in 1892 of a painting he had seen in an exhibition of symbolists; Monrad credits Felix Krämer for identifying the work as the four panels of Bonnard’s Women in the Garden (1891, Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Hammershøi could not remember the painter’s name, but mentioned a spotted dress and "the little doggy" in a rare observation on the work of his contemporaries (41–42). Two decades later, the Statens Museum for Kunst acquired a Bonnard, The Milliner (1907, Dep. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen). Purchased in 1911 from the Copenhagen dealer Valdemar Kleis, it is one work by a French painter in the present exhibition that Hammershøi must surely have seen. The Milliner and Woman in Front of a Mirror (ca. 1905, Neue Pinakothek, Munich) hung next to Edvard Munch’s Night in St. Cloud (figs. 17 and 18). On the adjacent wall was Hammershøi’s Interior with a Young Man Reading (1898, The Hirschsprung Collection, Copenhagen), for once with Svend Hammershøi, rather than Ida, at the window.

Corners like this one in the fifth room serve as reminders why exhibitions can be worth the risk and expense. The Munch painting—as much as the Whistlers and Fantin-Latours in the show— dates from another era. It is one of several repetitions of a key work from 1890, the response to the death of Munch’s father in November 1889. Munch, who had arrived in Paris a month earlier on a government stipend, became deeply depressed when he received the news from his aunt in Oslo. Late in December he moved into a hotel room overlooking the Seine on the Quai Carnot in the suburb of St. Cloud. There he developed ideas that resulted in the "St. Cloud Manifesto," among them, his famous statement written after an evening in a music hall: "One shall no longer paint interiors, people reading and women knitting. They will be people who are alive, who breathe and feel, suffer and love" (Munch Museum MM UT 13, p. 7).[29]

Displayed next to Bonnard interiors in a room otherwise lined with Hammershøi interiors, Munch’s Night in St. Cloud offers an intriguing contrast. A Munch "nocturne" from 1890, The Seine at St. Cloud, confirms that both Nordic painters were admirers of Whistler. Other works with the same title from 1890 suggest Munch’s equally vivid response to French art. Munch and Hammershøi arrived in Paris for a second stay at about the same age: Munch turned twenty-six in December 1889, and Hammershøi was twenty-seven when he arrived in 1891with his wife, Ida. By the time they were forty, the Norwegian had undergone a complex metamorphosis; the Dane had not. Munch had found an important patron by 1903, the German ophthalmologist, Dr. Max Linde; he had become a master printmaker and was drinking to excess. Hammershøi had also found a major collector, the Danish dentist, Dr. Bramsen, as well as a patient wife and a beautiful apartment.

On the walls opposite the Bonnards and the Munch in the fifth room hung a dozen interiors by Hammershøi. With close study, some changes over time can be discerned (fig. 19). The earliest canvas dated from 1893, an arrangement with a white door and a woman seen from the back. Another work from the mid-nineties, predating the move to the Strandgade, shows two women at a pair of windows; their heads and black skirts dissolving in a haze of light, reminiscent of Hammershøi’s tree trunks against the sun. A later painting with a single figure next to the two women—Interior, Frederiksberg Allé (1900, private collection, United Kingdom)—is more precise; Monrad explains that Hammershøi had worked from a photograph (80). Visitors lingered at Interior, Strandgade 30, where Ida could see the façade of the Asiatic Company building across the street through her window; the painter was fond of his windows, but rarely indicated what was outside the room. To arrange this picture, he had apparently removed all the chairs, except the one Ida leaned on with one knee; either she or the chair seems to lack a foot, and the antique Andreas Marschall square piano was missing a back leg (fig. 20).

In the sixth gallery ("The Empty Room"), the paintings without Ida were even more surreal (fig. 21). In Interior with the Artist’s Easel (1910, Statens Museum for Kunst), perhaps a symbolist reduction of Johannes Vermeer’s The Art of Painting, light falls from a window to the left of the painter’s silhouetted easel, glinting on the edges of the gold frame of an engraving on the wall.[30] Through the open door a porcelain bowl in the adjacent room also catches the light. Next to that painting in Munich hung another view of the same room with a card table holding a plant, and the piano against the wall. For the second canvas, Interior with Potted Plant, the artist placed the bowl, a favorite prop, on the piano (fig. 22). The artist painted both pictures in an apartment at Bredgade 25, the Hammershøis' second move after they had to give up Strandgade 30 in 1909. Earlier, in the Strandgade, he had painted the framed print hanging low, directly above the piano in The Music Room (1907). The interiors empty of inhabitants illustrate Peter Nørgaard Larsen’s remark in his essay: "Horizontal and vertical, doorways and windows, figures and objects, easels and punch bowls; everything is used like set pieces combined to form the most perfect scenes thanks to the supremely gifted touch of the director" (191).[31]

The painting Artemis dominated the seventh room ("Antiquity and the Nude"), a narrow passage with only three paintings by Hammershøi and two by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, then universally admired (fig. 23). Museum-goers in Munich had an opportunity to see Puvis’s Young Woman by the Sea (1882, Neue Pinakothek, Munich) in a new context. Next to it was his earlier work Young Girls by the Sea, a smaller version of a painting shown at the Salon of 1879 and lent by the Musée d’Orsay. During his stay in Paris in 1891–92, Hammershøi carefully copied a Greek relief of the three Graces at the Louvre; the result of his efforts was on loan to Munich from the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek.

Artemis, painted immediately after the Hammershøis had spent several months in Italy, has introduced an endless series of question marks into the literature. Monrad asks, among other questions: Was the androgynous male figure Paris or Apollo? (25). He reveals that after completing this large canvas in 1894, Hammershøi halfheartedly named it Artemis when a title had to be found for Den Frie Udstilling. A critic, Emil Hannover, commented in a positive review for the newspaper Politiken (May 4, 1894): "It is . . . a picture which in ordinary terms represents nothing" (25). Hvidt quotes from Hannover’s praise of the subtle beauty even in its flaws; she herself discovers in the painting "a photographic sensuousness" (206). Patricia Berman also sees the influence of Puvis, claiming that Artemis "represented a new disembodied, static aesthetic, a suggestion of painting as a realm of artifice and internal logic."[32] Whatever the artist intended with his nearly identical female nudes and the tentative male figure, Hammershøi did not repeat this venture into mythological subjects, Monrad notes (25–28). The Statens Museum for Kunst bought Artemis from the sale after the artist’s death in 1916. It would be more than ten years before he painted another nude; the Danish national gallery also acquired that anomalous picture from 1909–10, which hung with Artemis in the seventh room in Munich.

The eighth room, spacious and slightly eerie, was entitled "The Empty City." It included seven Vilhelm Hammershøi paintings, all but one void of human life (fig. 24). Even the Svend Hammershøi chosen for this group of pictures represented a desolate exterior view of the National Museum of Denmark: The Garden of Prinsens Palæ (ca. 1906, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen). Two paintings of the narrow inner courtyard at Strandgade 30 were included in this section on the urban scene; in one of them, Ida looks down from a window (fig. 25).[33] For some exhibition-goers, this tour led by the Hammershøi brothers may have awakened an illicit longing for the bustling Copenhagen street scenes of Paul Gustave Fischer. Such a wish was not to be fulfilled on these walls, and the cityscapes by international artists in the room were as depopulated as those of the Hammershøis. Two lovely Dutch views of boat traffic in Amsterdam and London by Eduard Karsen and Willem Arnold Witsen showed no human beings at work, and Karsen’s Beguinage in Amsterdam had only a single woman in residence. The white horse traversing a glistening cobblestoned street in Jozef Pankiewicz’s magnificent Warsaw Cab at Night (1893, The National Museum, Warsaw) was the liveliest spot in the gallery. In another outstanding painting in this room, Morning Departure, Luigi Selvatico tempted modern viewers into looking for a story. Hammershøi works have teased art lovers in this way ever since his solitary figures first began to appear at exhibitions in the 1890s, just as Edward Hopper paintings do today (fig. 26). For the Munich exhibition, an introductory panel provided a mode d’emploi warning to dissuade visitors from seeking narratives in Hammershøi canvases. The pictures selected for "The Empty City"—described in a wall text as "a silent, immobile, and uninhabited world"—suggested that not only the Danish painter, but other European artists had tried to "stay the hands of time" by evacuating dwellers of the rapidly changing urban environment.

The exhibition ended in a ninth room ("Self-reflection") with two self-portraits, both from 1911. The couple spent the summer weeks that year in Lyngby, only ten miles north of Copenhagen. There they rented a picturesque country house called Spurveskjul (Sparrow’s Hole), built in 1805 by the Danish painter N. A. Abildgaard. Instead of turning to landscapes, Hammershøi painted himself in the pleasurable framework of the house. He included Ida, her back to the viewer, in their double portrait in an oval mirror. The picture is now in the collection of the optometrist and organic farmer Professor Günther Fielmann at his country house Schierensee Manor in Schleswig-Holstein. The other product of the summer was a pure self-portrait, with the painter at the left edge of the canvas. His preferred subject matter, apart from his wife, filled the right margin of the picture: a white door and a window (fig. 27).

The generous spaces of the Hypo-Kunsthalle in Munich offered vistas through openings into adjacent rooms, recalling the doors and window walls the painter adored in his apartments.[34] With gallery colors alternating between steel blue or dusty puce, strong tones on the walls complemented the muted colors of Hammershøi’s palette. An ample hanging allowed the pictures breathing space and gave visitors enough elbow room to move easily from one canvas to another. The more closely hung interiors permitted comparison, yet enabled the viewer to back away for a new perspective. Seeing rows of black-clad Idas, one after another, was an unforgettable experience. The works assembled as international parallels were apposite and fresh.

The exhibition catalogue, produced in Denmark and published by Prestel, has a wealth of good reproductions and top-quality essays with useful new material, particularly in those by Stevens and Hemkendreis. Satisfying to read straight through, Hammershøi and Europe is difficult to consult. Like most Prestel catalogues in recent years, it lacks individual entries and an index, and thus offers little sustainable pleasure. The checklist, arranged chronologically, could have benefited from thumbnail illustrations, necessary for an artist who called so many of his pictures simply "interiors."

Also missing in this catalogue about the painter’s international connections was a precise list of his own exhibitions and those shows in Copenhagen or abroad in which he might have seen works by the artists mentioned or included in the catalogue. Monrad discusses some potential points of contact with other European painters in various thematic sections of his essay. He compares, for example, the treatment of wall surfaces and windows in Hammershøi and Selvatico, speculating on the possibility that the Danish artist, visiting Rome in 1902–03, might have noticed the Italian painter’s Morning Departure (48–50). Stevens also conscientiously tracks possible social or artistic contacts with British artists. Tone Bonnén, in her excellent eight-page alphabetical section of biographies, clarifies to a large extent for most painters those places where Hammershøi would have had an opportunity to come across their work. A supplementary tabular presentation, beginning with those artists in the show who exhibited at the International Exposition in Paris in 1889, would nevertheless have been helpful. Had Bonnén’s biographical pages been indexed, it would have been easier to learn a number of other interesting conjunctions, for instance, that Bonnard and Pankiewicz painted together in southern France in 1908 (229).

The catalogue for Krøyer: An International Perspective, the exhibition shown in 2011–12 at The Hirschsprung Collection and in Skagen, is a handsome model in this respect. With a separate chapter related to each foreign counterpart artist, signed individual entries for all 137 works in the show, a chronology of the artist’s life and movements, a superb "Expography" by Iben Johansen, and—most importantly—an index of names (with life dates), the Krøyer catalogue set the bar extremely high for placing a painter within the context of his contemporaries.

Hammershøi and Europe in Munich’s Kunsthalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung was perfectly installed and lit; the gallery spotlights used a sensitive focus, never harsh, with a diffused light spilling around the frame. The exhibition provided an extraordinary opportunity to see Hammershøi alongside some of his most relevant and better-known contemporaries: Whistler, Matisse, Bonnard, Gauguin, Carrière, Khnopff, Munch, and others. Equally rare was the chance to compare his silence with that of Karsen, Stott, Selvatico, Pankiewicz, Hans am Ende, or Witsen. To bring Artemis and the Greek Relief to hang in Munich opposite Puvis was an achievement in itself. A delight to visit, this show deserved a better permanent record. That the Kunsthalle promoted the artist as "this modern Nordic Vermeer" was entirely appropriate. The phrase from a critic in 1909 reviewing Hammershøi’s works on view at the Glaspalast was more than a catchphrase for Munich: it is a suggestive approach to the Dane’s vision of his intimate world.[35] And if prices for Hammershøi paintings soar past the auction records of 2012, this Nordic Vermeer may soon have his own Han van Meegeren.

Jane Van Nimmen

Independent scholar, Vienna, Austria

vannimmen[at]aon.at

[1] The Statens Museum for Kunst website inventory lists forty-four paintings and fifteen Hammershøi drawings in their holdings. The museum selected twenty of their Hammershøi paintings for the Copenhagen exhibition and added five more to the Munich showing; four drawings from the national collection were shown in both venues, among only six drawings in the show. Various lenders added paintings to the exhibition in Munich, compensating for four paintings from Ordrupgaard restricted to the Copenhagen venue.

[2] Patricia G. Berman, In Another Light: Danish Painting in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Vendome Press, 2007), 224; see especially chapter 7, "Hammershøi and Urban Places."

[3] Press your browser’s refresh button or F5 to reload the screen when necessary in the online edition of the Glaspalast exhibition catalogues from the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Hammershøi’s Danish colleagues Carl Holsøe and Peder Severin Krøyer also won medals in 1891. Krøyer’s Committee Meeting for the French Exhibition in Copenhagen(1888, The Hirschsprung Collection, Copenhagen) was the largest work in the Danish section. Another medal in 1891 went to Max Liebermann; the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlung bought Liebermann’s In the Dunes (1890, Neue Pinakothek) from the exhibition.

[4] For Hammershøi’s four entries, see Illustrierter Katalog der VI. Internationalen Kunst-Ausstellung 1892 im Kgl. Glaspalast (Munich: Verlagsanstalt für Kunst und Wissenschaft, 1892). In 1892 the Bavarian state bought from the exhibition one of Krøyer’s largest paintings for the Neue Pinakothek; this remarkable work, Group of Fishermen on the Beach at Skagen (1891, private collection) was deaccessioned in 1936. On Krøyer, see the astute study by Thor J. Mednick, "Danish Internationalism: Peder Severin Krøyer in Copenhagen and Paris" in this journal (Spring 2011).

[5] The illustration accompanied an article by the Danish painter N. V. Dorph, "Moderne Kunst in Daenemark," Pan 4 (1898, no. 2), 132a. Hammershøi had shown a work under the title An Old Woman at the Glaspalast in Munich in 1892 (cat. no. 700). See Anne Schulten, Eros des Nordens: Rezeption und Vermittlung skandinavischer Kunst im Kontext der Zeitschrift Pan, 1895–1900 (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2009), 132–39. According to Schulten (145–6), the Danish critic Emil Hannover, a friend of Hammershøi’s, had been commissioned to write the article for Pan, but could not come to terms with the journal.

[6] The 1909 catalogue illustrated Interior, one of Hammershøi’s seven entries. The artist also sent two paintings to the 1913 international exhibition in Munich.

[7] Kirk Varnedoe, Northern Light: Realism and Symbolism in Scandinavian Painting, 1880–1910, exh. cat. (New York: Brooklyn Museum, 1982), followed by his book, Northern Light: Nordic Art at the Turn of the Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988). Poul Vad (1927–2003) published a substantial new edition of his 1957 monograph in Danish, Hammershøi, vaerk og liv (Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1988), and an English edition followed, translated by Kenneth Tindall, Vilhelm Hammershøi and Danish Art at the Turn of the Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

[8]Vilhelm Hammershøi, 1864–1916: Danish Painter of Solitude and Light, curated by Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark and Mikael Wivel, in collaboration with Henri Loyrette and Robert Rosenblum, exh. cat. (Copenhagen: Ordrupgaard, 1998).

[9] Felix Krämer and Ulrich Luckhardt, with Barbara Ludwig (published in cooperation with Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen), Vilhelm Hammershøi, exh. cat. (Hamburg: Kunsthalle / Christians, 2003). The catalogue included an essay by Kasper Monrad, "Vilhelm Hammershøi – ein internationaler Künstler," 93–102.

[10] See Susanne Meyer-Abich, Vilhelm Hammershøi: das Malerische Werk (diss., Rühr-Universitat, Bochum, 1995).

[11] See Hammershøi, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts; Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2008). In addition to essays by Krämer and Sato, the catalogue included a study by Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark, director of Ordrupgaard, relating Hammershøi to the Golden Age of Danish painting in the first half of the nineteenth century; the catalogues for the show in London and Tokyo used the same painting on the cover as the earlier Hamburg show: Interior with Young Woman Seen from Behind, Strandgade 30 (ca. 1904, Randers Kunstmuseum, Randers).

[12] The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York also acquired its first Hammershøi works in 2012: Moonlight, Strandgade 30(1900–1905) and a chalk drawing from 1891.

[13] Two other Hammershøi paintings in the same sale at Sotheby’s, London (L12101) more than doubled their top estimates and sold for over $1 million. The two remaining lots (nos. 32 and 33) of the five in the sale sold for more than half a million dollars each, also doubling their estimates.

[14] On Hammershøi’s formal training, see Vad (1992), 20-24. Krøyer’s support is mentioned in an essay by Marianne Saabye, "Mood Painting," in the magnificent catalogue Krøyer: An International Perspective (Copenhagen: The Hirschsprung Collection and Skagens Museum, 2011), 113. Hammershøi sold the portrait to the collector Heinrich Hirschsprung in 1896; see Vad (1992), note 36, 413.

[15] See Krämer’s entry in the useful illustrated chronological catalogue in Hammershøi (London 2008), cat. no. 5, 143; see also Vad (1992), 101 and 420, note 138.

[16] Vad (1992), 100–02 and 421, note 140. In 1904 the picture entered the collection of Hammershøi’s first patron and chief supporter, Alfred Bramsen.

[17] See Berman on Den Frie Udstilling, In Another Light (2007), chap. 6, 195–219. On Willumsen and the society’s first exhibition, see the absorbing article by Gry Hedin in the Autumn 2012 issue of this journal.

[18] Henry Madsen, a writer and Egyptologist, was the oldest son of the painter Karl Madsen. The young man’s father, a close friend of Hammershøi, had begun a museum career in the 1890s that would lead to the directorship of the Statens Museum for Kunst in 1911 and the Skagen Museum in 1928.

[19] The charcoal and chalk drawing for Evening in the Drawing Room (1891, The David Collection, Copenhagen) provided a welcome accompaniment to the painting.

[20] Like Hammershøi, Ilsted won a medal at the International Exposition in Paris in 1900. He became a master printmaker, developing after 1909 a remarkable expression in mezzotints. See Peter Ilsted (1861–1933): Sunshine and Silent Rooms, exhibition 1991, exh. cat. (Buffalo Grove, Illinois: Merrill Chase Galleries, 1990).

[21] The young woman seen left of Ida in the painting is her sister-in-law Ingeborg Ilsted, her brother Peter’s wife. To Ida’s right, in the pose of Whistler’s mother, is Anna Hammershøi.

[22] Gauguin’s Danish wife Mette Gad sits next to Ida in a photograph (ca. 1901) preserved at the Royal Danish Library showing a social gathering of artists; Vilhelm Hammershøi stands in the back row behind Mette.

[23] Anne Hemkendreis, "The Essence of Things: Hammershøi as Seen through the Eyes of Rainer Maria Rilke" (165–79). Rilke’s interest in traveling to Denmark in 1904 arose through reading the work of J. P. Jacobsen, especially his novel Niels Lyhne (1880); Hemkendreis notes that the novel was in Hammershøi’s library (168).

[24] Rilke, with his passion for trees, might have appreciated the work of Vilhelm’s younger brother, Svend Hammershøi, who would become a noted ceramic artist. Svend’s Landscape 1901 hung with his brother’s paintings in the third room in Munich.

[25] For Naoki Sato’s catalogue entry on this landscape, see Hammershøi (London 2008), cat. no. 33, 150. An app produced for the Copenhagen venue of Hammershøi and Europe begins with the Fortunen landscape and cites Hammershøi’s comments on English trees in a letter to his brother from London during the winter of 1905–06.

[26] Both the children of the prominent dentist and art lover were in London when the Hammershøis arrived in 1897. Henry Bramsen (1875–1919) was building his career as a solo cellist. He was married to the Danish singer Marta Sandal from 1903 until 1910, touring the United States in those years as a soloist and member of the New York Quartet and various orchestras. For that reason, Alfred Bramsen identified The Cello Player as The Young Virtuoso, Mr. Henry Bramsen, when he included it among eleven Hammershøi works from his collection sent to the United States for the Scandinavian Art Exhibition in 1912–13. The successful show sponsored by the Scandinavian-American Society traveled from New York to Buffalo, Toledo, Chicago, and Boston. Karen Bramsen (1877–1955) was studying violin in London at the Guildhall School of Music in 1897–98. She married Gustav Falck in 1903; her husband later became director of the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen.

[27] Whistler returned for only a day on May 16, 1898, to attend the opening at Prince’s Skating Rink, Knightsbridge, of the first exhibition of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers. In her catalogue essay, Stevens cites a letter from Whistler to Henry Bramsen, thanking the cellist for showing him works by Hammershøi. Further correspondence in The Hirschsprung Collection archive reveals Hammershøi’s vain hope that Whistler would add his new London paintings—Two Figures: The Artist and his Wife and Portrait of Karen Bramsen—to the group’s first show in Knightsbridge (152, and n. 71, 162). Hammershøi finally participated in the fourth exhibition of the society, held in the New Gallery, January–March 1904; he showed the beautiful Interior (1899; Tate, London) from the collection of the concert pianist Leonard Borwick, as well as a landscape shipped from Copenhagen by Alfred Bramsen (155).

[28] In An Artist’s Gathering, a painting purchased in 1903 for the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, the Danish painter Viggo Johansen depicted Hammershøi seated at Bindesbøll’s left. Johansen had invited them in 1901 to a dinner in honor of Prince Eugen of Sweden. On Hammershøi’s two group portraits of gatherings in his own apartment, see Vad (1992), 212–34.

[29] Munch moved into the Hotel Belvedère in St. Cloud with the Danish poet Emanuel Goldstein (1862–1921) and the Norwegian Georg Stang. He remained in touch with the Dane, and during his nine-month stay in Copenhagen in 1908–09, Munch dedicated an impression of the drypoint version of the painting to his friend "in remembrance of our companionship St. Cloud 1889–90." See Gerd Woll, Edvard Munch: The Complete Graphic Works (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2001), 56, cat. no. 17. Woll writes that Goldstein was probably the figure in a top hat at the window.

[30] The engraving by Johann Friderich Clemens of The Battle of Copenhagen, April 2,1801by Christian August Lorentzen is illustrated in Berman, In Another Light (2007), 63, fig. 38. (In link above, scroll down for color image of Lorenzen painting). Although the English fleet under Horatio Nelson defeated the Danes, the battle nevertheless marked the beginning of the Danish Golden Age. Hammershøi might well have placed the patriotic print in his composition unobtrusively but deliberately in the position of the map of the Seventeen United Provinces on the wall behind Clio and the easel in Vermeer’s The Art of Painting.

[31] Hammershøi was selective in arranging his compositions, with or without figures. He told an interviewer in 1907: "When I choose a motif, I think first and foremost about the lines" (cited by Krämer in his essay "Poetry of Silence" [London 2008], 24). In this sixth segment of the show, an exhibition-goer lost in the puzzling geometry of rooms opening one into another through series of doors could consult photographs and a framed floor plan of the Strandgade apartment as a guide. For the plan, see Vad (1992), 186–89, and Vilhelm Hammershøi (Hamburg 2003, as in note 9 above), 17.

[32] Berman, In Another Light, 202 and fig. 161.

[33] A slightly larger version, also with Ida’s face, of Courtyard Interior at Strandgade 30 (ca. 1905, Collection of Ambassador John L. Loeb Jr., New York) is illustrated in Berman, ibid., fig. 196.

[34] A few critics at the Copenhagen venue found the museum’s hanging too tight to be comfortable. See the review by Clemens Bomsdorf for Art: das Kunstmagazin (May 5, 2012).

[35] The Glaspalast, Munich’s largest exhibition building, was destroyed by fire in 1931. It was replaced by the Haus der Kunst (1934–37) on the Prinzregentenstraße, designed by Paul Ludwig Troost.