The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Prologue

Commodore Perry’s journal of his voyage from Japan contains the entry, “8 boxes, 13 dolls.”[1] Lacking any further description, the entry is part of an inventory of items received by the US Naval Captain during the signing of the 1854 Kanagawa Treaty. To commemorate the official opening of Japan’s borders to foreign trade, the two nations exchanged “diplomatic gifts,” privileged cultural objects intended to display national achievement and commercial power. Accordingly, the United States presented to Japan such items as a telegraphic device and a miniature train, while Japan’s gifts included brocades, porcelains, and lacquerware. And yet the “13 dolls” remain somehow unaccounted for in this political context, their purpose elusive among the more overt status claims of their surrounding objects. What values did the dolls embody to be included in Japan’s official entourage of national product emissaries?

Several of the dolls survive and offer clues. One of these is of a type known as gosho, which depicts an exaggeratedly plump young boy, often holding a symbolic attribute (fig. 1).[2] The term gosho means old palace (御所), and indeed gosho dolls were associated with the imperial court from the early Tokugawa, or Edo era (1603–1868), such being their prestige that the emperor awarded the dolls to daimyō (feudal lords) in official recognition of worthy tribute received. But beyond being tokens of status, however exalted, gosho dolls were also thought to possess talismanic properties, and were revered as being auspicious. Women embarking on a journey, for instance, carried with them a gosho doll to avert trouble; the dolls also were sometimes placed in household shrines as a means to attract beneficial forces to those in its orbit.[3] Simultaneously totem and toy, religious amulet and political prize, in this way gosho dolls functioned on a number of levels at once, blurring the borders between the sacred and secular.

In light of their historical connection to imperial power, the diplomatic gift of dolls is somewhat clearer. Still, the question remains: why dolls? More importantly, what did these charged, polyvocal objects portend for Japan’s modernity?

Introduction

This is an essay about dolls, or more properly, the meanings that are invested in the making of dolls, and the subjectivities produced by engaging with dolls. In particular, it explores the relationship between dolls and modernity as it was created and experienced in the context of Japan. I want to propose that dolls played a critical role in the imaginative process by which Japan constructed its modernity; that, rather than being jettisoned to make room for “progress,” dolls were instrumentalized to negotiate that progress, serving as central vehicles through which foreign ideas were processed, reconfigured, and transmitted. In so doing, dolls themselves became constitutive sites of Japanese modernity: material “re-makings” of “worlds already on hand.”[4] And through their evolving technologies of manufacture, display, and diffusion, dolls vitally arbitrated the production of knowledge by which Japan made its modern world.

Of special concern here is the meeting of “old” and “new” worldviews. While this intersection has been characterized historically in terms of contestation and rupture—sacred versus secular, traditional versus modern, etc.—I suggest Japan’s modernization was neither so abrupt nor so disjunctive as presumed, and that its dolls were material witnesses to vibrant confluences of old and new paradigms, in particular that of myth and science. In this regard, Stephen Greenblatt has characterized the peculiar allure of exhibited objects according to what he describes as their “resonance” and “wonder.” As he writes:

By resonance I mean the power of the displayed object to reach out beyond its formal boundaries to a larger world, to evoke in the viewer the complex, dynamic cultural forces from which it has emerged and for which it may be taken by a viewer to stand. By wonder I mean the power of the displayed object to stop the viewer in his or her tracks, to convey an arresting sense of uniqueness, to evoke an exalted attention.[5]

Affective as discrete qualities, resonance and wonder can also operate together in the same object as alternating or even simultaneous modes of engagement. I introduce these terms here because I mean to employ them throughout as a way to register the rich and layered significance of dolls in Japan’s process of modernizing.

My premise for this unorthodox exploration derives from recognition that there are multiple modernities, and that the unique character of any given one is shaped by imaginative practices. As Arjun Appadurai has observed, the cultural imagination is the “constitutive feature of modern subjectivity,” that which "is now central to all forms of agency . . . and is the key component of the new global order."[6] In this imaginative, world-making process, it is the objects of everyday life that figure so prominently and indispensably, and that in a felt, experiential way both contour and constitute our being in the world.[7] Dolls are privileged objects because, on a basic level, they are embedded yet mobile objects; bearers of deep-rooted communal values, dolls are also easily migratory, facile intercessors in a wide range of human affairs. This is especially so in modernizing Japan as dolls became vital sites of commerce and intercultural exchange. In this sense, the essay speaks to what might be called “the social life of dolls.”[8]

On a deeper level, dolls are privileged objects because they are mimetic, linking them innately to the human body, and thus to particular affect. As material mirrors that both reflect and oppose perception, dolls uniquely supplement human self-affection.[9] Applied intensively to a cultural collective, it may be appropriate to speak of doll-engagement as a “technique of the self,” a particular kind of the “procedures . . . suggested or prescribed to individuals in order to determine their identity, maintain it, or transform it . . . through relations of self-mastery or self-knowledge.”[10] In Japan, dramatic shifts in scale and verisimilitude were the hallmarks of modern dolls, suggesting a rarified form of collective self-knowledge, as well as self-affection. By exploring the enigmatic quality of this relationality, the essay contributes to a comparative aesthetics of modern media techniques.

Finally, I want to clarify my usage of the key terms: Japanese modernity, “the West,” and “doll.” Scholarly consensus aligns the Tokugawa, or Edo, era with Japan’s early modernity, due at least as much to the sophisticated urban infrastructure that developed during that period as to the presence of burgeoning foreign influence. I follow the contours of that consensus here, but apart from its historical and temporal lineaments, I neither ascribe to nor espouse a succinct conception of Japan’s experience of modernity. Rather, I invoke what Homi Bhabha has described as the “transitional social reality” of modern nations as a general framework for approaching the complex specificity of Japan’s modernity.[11] That is to say, instead of narrating a fixed notion of Japan’s modernity, I characterize that modernity as an ambiguous and unstable ideological field, energized by particularized socio-economic, political, and cultural forces generated both internally and externally; a field onto which I offer a new vantage via the material ideas of its dolls.[12] My strategy here is thus not to delimit Japan’s modernity to the terms of extra-cultural interaction, much less to one set of exchanges within such interaction. On the contrary, by examining key instances of such dialogue through the prismatic lens of Japan’s dolls, I seek to expand and enrich understanding of the larger transitional field that is Japan’s modernity.

Likewise, my reference to “the West” is intended not to indiscriminately aggregate the many modernities comprising Europe and the Americas, any more than it is meant to act as a monolithic foil for defining Japan’s modernity. Instead, I use this term within the limited scope of this essay as a marker to designate a range of distinct foreign forces, a multiplicity that, relative to Japan, shares certain paradigmatic features. Primary among these features are the valorization of science and of scientific modes of investigation.

As for the term “doll,” I employ it according to its usage in the context of modern Japan, one that is significantly enlarged and altered from the Western conception of doll with its nearly exclusive reference to a child’s toy.[13] Dolls in Japan are defined ambiguously, as suggested by the very word for doll, ningyō (人形). Composed of the characters for human and shape, the Japanese doll even at the semantic level is unlimited as to category, size, or usage. In social practice as well, dolls encompass a spectrum of human-shape objects, a fact reflected in the definition of doll offered by the eminent historian Tokubei Yamada, in his compendious study of Japanese dolls. He writes that, with very little exception, dolls may be understood simply as “things made in the shape of a human.”[14] All the dolls I examine in this essay were identified specifically as ningyō throughout Japan’s early and high modernity (and, in fact, continue to be referred to as such).

The essay is organized into three sections, followed by a conclusion. I begin by introducing the historical significance and functions of dolls within Japanese society. In the following section, I examine the re-making of the historical uses and meanings of dolls in the Edo era, focusing in particular on the evolution of the mechanical doll, and the anatomical doll. The third section is devoted to the “modern doll” that consummates the technologies and concepts embodied in the previous dolls, and which bridges the late Edo and Meiji (1868–1912) eras.

I. Animated Objects, Ambiguous Bodies: Placing Dolls In Pre-Modern Japan

Japan possesses one of the richest traditions of dolls in the world. From the origins of Japan’s history and continuing unabated to the present, dolls are a pervasive feature of Japanese society. One way this is seen readily is that, unlike many societies, in which dolls reside primarily in the sphere of children, a great number and variety of dolls in Japan circulate among adults, often given as prestigious gifts at important cultural events such as weddings, company promotions, or affairs of state. Japan’s culturally iconic and multi-streamed tradition of doll-theater (puppet-doll theater, and mechanical-doll theater, among other types) is another demonstration of the centrality of dolls in Japan, as is the widespread phenomenon of keeping some type of household display for dolls.[15] But perhaps the most extensive index of the vibrancy of Japan’s doll tradition is its sheer cultural saturation. Produced in a bewildering variety of styles and sizes, and serving a diverse array of functions, the profusion of dolls in Japan permeates every domain of culture, from business to theater, religion to science, domesticity to art.

Even more remarkable than the social prominence and ubiquity of Japan’s dolls is the ambiguity that characterizes their human engagement. That is to say, the perceived boundaries between humans and dolls in Japanese culture are often indeterminate. In one sense, as body-doubles, the sheer abundance of Japan’s dolls intensifies the reflexivity of the human-doll relationship. But this ambiguity occurs more fundamentally through residual beliefs and practices deriving from Japan’s traditional religious framework, which blends Shinto with Buddhism. Shinto’s animistic beliefs attribute deific presence to the forces and objects of nature, producing a vital and affective field of energies that interpenetrates daily life.[16] Likewise, Buddhism’s multiple invisible realms, as well as hosts of deities, variously overlay and impinge upon the quotidian human world. The intertwining of these beliefs in Japan produced over time a religious ethos and praxis characterized by principles of ambiguity: ideas and practices that express an underlying sense of fluidity between the realms of the latent and the manifest, the living and the dead, the human and the non-human.

Objects figure centrally within these beliefs as mediators between the worlds of human and divine, and are imparted a quality of imminence.[17] That is, inanimate objects are not viewed as inert, lifeless matter, but rather as possessing self-emergent capability. This is well demonstrated in the consecration, or “eye-opening” ceremonies for Buddhist icons, by which the mimetic form is believed to “transform [from] a mere likeness into a divine presence.”[18] Likewise, the founding narratives of many Buddhist temples recount the miraculous deeds of their animated icon. No less potent is the vast system of ritual objects utilized in Buddhist devotional practice; charged with a transformative power, such objects are essential tools with which practitioners develop or transform themselves spiritually.[19] Japanese folklore similarly abounds with stories of inanimate objects that come to life or otherwise metamorphose. This is particularly true for objects of human use, which are thought to become sentient over time, and can even be capable of malice.[20] This belief is reflected playfully in a woodblock print depicting anthropomorphized tools, entitled The Whispering and Gossiping of Various Tools (fig. 2).

Such beliefs are evidenced perhaps most vividly in the practice of kuyō (供養), or mortuary rites for inanimate objects. In these Buddhist ceremonies, objects of long-term use are ritually purified and memorialized, either by burial or by cremation.[21] The literal equivalency between objects and humans drawn by this ritual is emphasized in the word kuyō itself, which means “to give offerings to nourish.”[22] It is significant in terms of the continuation of Japan’s traditional beliefs, and the consequent resonance of its objects—dolls in particular—in modern Japan, that kuyō memorial services are a pervasive component of contemporary Japanese cultural practices. In fact, as Fabio Rambelli notes: “The vast and fluid field of memorial services is arguably one of the most significant social and cultural contributions of Buddhism in contemporary Japan.”[23] Throughout the year in Japan, kuyō services are held for a wide range of objects that have grown old through use, so to speak. Prominent among these are such things as sewing needles, eyeglasses, writing brushes, fans—and especially dolls. Indeed, kuyō for dolls is one of the most common, and celebrated, of the mortuary rites for inanimate objects (fig. 3).[24]

Within these ideas and practices that make amorphous the borders between the living and the non-living, Japan’s dolls are objects doubly charged. That is, the imminence, or transformative potential, imputed to dolls as objects of close human use, is amplified through their human resemblance. Accordingly, it is not surprising that dolls in Japan have served variously not only as talismans but as human surrogates.[25] For instance, the hina doll that is still given to girls at annual festivals today functioned originally as a human scapegoat, where it was used to symbolically collect toxins and then was floated out to sea.[26] Further, this highly charged, or wondrous, quality imputed to Japan’s dolls is intensified by what may be described as a certain congruency between dolls and devotional images. While icons in Japan are not referred to typically as dolls, in practice there is overlap between these two classes of mimetic objects.[27] This is due not only to the sentience invested in both icons and dolls, but also because historically dolls have performed as much in religious as in secular life; whether presented to temples as votive offerings, for instance, or displayed in the home as repositories of spiritual forces, doll bodies have been the enigmatic mediators of Japan’s closely imbricated worlds of sacred and profane, private and public, animate and inanimate.

Dolls continued to navigate the merging of worlds in Japan’s modernity, for the multivalence of dolls throughout Japan’s pre-modern history informed their resonance as they evolved into new sites of wonder in Japan’s modernization. Instead of diminishing in cultural value, dolls became modern Japan’s foremost cultural idiom through which new ideas were literally translated and performed. Likewise, the ambiguous dynamic that characterized doll and human interaction in Japan’s pre-modern history intensified dramatically in modernizing Japan; the perceived mutability between doll and human bodies increased and literalized such that the world-making of Japan’s modernity may be said to be tantamount to the world-making of Japan’s dolls.

II. Machines and Corpses: Making Modernity in Japan

During the Edo era, under the military regime of the Tokugawa Shogunate, the period of sustained political stability gave rise to a complex urban society and a flourishing commercial culture that, by the eighteenth century, boasted the world’s largest population.[28] Likewise, Japan’s ideological infrastructure developed during the period to support a highly sophisticated array of cultural products. In terms of institutional and political governance, as well as cultural production, Japan already evidenced its own incipient modernity. As historian Willy Vande Walle has commented in this regard, “the Meiji and Taisho periods are the realization of something that was embryonic in the mid-Tokugawa period, was gestated in the late Tokugawa period, and burst into full bloom after the Meiji Restoration.”[29]

An important component of Japan’s early modernity was exposure to European knowledge. Based strongly in medicine and science, this knowledge came from the Dutch trading presence at the Western port of Nagasaki. As Timon Screech has shown, even though the Dutch were geographically circumscribed, their ideas and objects—such as optical devices and instruments—were not. Rather, these were diffused throughout Edo-era culture, where they exercised a formative influence. As Screech writes: “The scope of material exchange between Europe and Japan has . . . been sorely underestimated. Yet I would not imply that encounter was through goods alone.”[30]

Amid this thriving environment, Japan’s already-vibrant doll culture entered a new register of social significance as dolls literally took the center-stage of culture. This is evidenced with particular force in the emergence and evolution, during the Edo era, of several types of doll theaters: karakuri-ningyō (からくり人形), or mechanical-doll theater, and ningyō-jōruri (人形浄瑠璃), or puppet-doll theater, as well as the kabuki theater (歌舞伎), whose human actors modeled their gestures, narratives, and dramatic concepts expressly on those of the doll theaters. Together these three types of doll-theater dominated the cultural landscape of the Edo period, dynamically shaping the popular aesthetic language of its urban audience.

Further, dolls in modernizing Japan magnified the already-ambiguous relationship between dolls and humans in Japanese culture. Over the course of the Edo era, dolls developed in various ways that increasingly dissolved their distinction from living humans; scale was one way, verisimilitude another, and motion yet a third, all of which entailed the exploration of new ideas as well as technologies to realize. In ningyō-jōruri, for instance, its integration of increasingly large-scale and realistic puppet-dolls with multiple operators blurred the borders between doll and human bodies in a newly complex way. Likewise karakuri-ningyō complicated the human-doll divide with the progressively intricate sophistication of its simulated motion. And kabuki’s incorporation of dolls into the human body by means of gesture created an unprecedented type of human-doll enmeshment.[31] Moreover, all of these developments took place amid the exponential proliferation of dolls in society at large.[32] During the Edo era, doll production soared as never before, such that not only were dolls of every occasion widely available to all social classes, but new types of dolls were made based on thepuppet dolls of ningyō-jōruri, on the “people-dolls” of kabuki, and on the mechanical dolls of karakuri-ningyō: a profusion of doublings that in itself formed a type of doll-human blend.[33]

This amplified cultural presence of dolls, and the changes in doll design that intensified the melding of doll and human bodies, manifest the resonant force of Japan’s traditional beliefs about the imminence of objects amid modernizing conditions. In addition to the evidence of doll bodies, this resonance is exemplified in the emergence, during Japan’s early modern era, of popular legends surrounding the historical figure of Hidari Jingorō.[34] Active during the preceding Momoyama era (1594–1634), Hidari Jingorō was a craftsman of humble origin who became renowned for his skill at carving Buddhist figures so convincingly that they were said to come to life. Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s woodblock print depicting Hidari at work in his studio conveys a sense of his reputed animating power; the vividly emotive facial expressions and dynamic posturing of the carved figures that surround Hidari invest the objects with a forceful presence suggestive of imminence, if not pulsing blood (fig. 4). This tension in the scene is strengthened by the way Hidari’s gaze is turned away amid his carving; facing in the direction of the ferocious guardian statue glowering to his left, it is as though Jingorō has just been distracted from his work by a gesture or snarl from the feral figure.

This uncanny life-giving ability attributed to Hidari was not limited to religious subjects. In fact, perhaps the single-most famous legend about Jingorō recounts how he transformed a doll into a living woman. Comparable to the myth of Pygmalion in Western mythology, Hidari was said to have carved a large doll-portrait of a beautiful but unobtainable woman he admired. One of the more common versions of the story continues that the doll-portrait came to life after Hidari placed a mirror belonging to the woman inside the doll’s garments. Utagawa Kunisada’s rendering of this story shows the moment Hidari is startled in mid-drink by the motion and speech of his living doll (fig. 5). What is more, Kunisada’s image depicts a kabuki actor playing the part of Hidari with his living doll, one of innumerable such images; for throughout the entire Edo period, and continuing unabated into the Meiji era, the legend of Hidari Jingorō’s living dolls was as much a cultural phenomenon as the abundance of actual dolls themselves. Indeed, considering that kabuki may be considered a theater of “people-dolls,” that kabuki actors frequently performed subject matter about dolls that metamorphose into people adds another layer of meaning to the superabundance and nebulous quality of doll doubling in Japan’s modernization.

In such ways as this, the legend of Hidari Jingorō, along with the dolls themselves, manifested and perpetuated the transfiguration of Japan’s traditional world-view in the process of modernization. As the following sub-sections show, this process is witnessed with particularity in two types of dolls—mechanical dolls and anatomical dolls—because of their key roles in facilitating the trajectory of the life-like doll animation that came to emblematize modern Japan by the Meiji era. These two doll types are distinguished also by the explicit influence upon their design and manufacture by foreign knowledge constructs.

Mechanical Dolls

Like ningyō-jōruri, mechanical dolls, or karakuri-ningyō, were not new to modernizing Japan. The twelfth-century collection of stories known as the Tales of Times Now and Past, for instance, describes what may be the earliest karakuri-ningyō as the Heian era (794-1184) “water-boy”: a 4-foot tall doll that held over its head a jug which, when filled with water, tipped over and splashed the doll’s face.[35] Also like ningyō-jōruri, which had been used to perform Buddhist didactic stories, karakuri-ningyō in pre-modern Japan were associated with religious activities and events.[36] During the Kamakura period (1185–1333), for example, monks at Nara made lanterns that featured small karakuri-ningyō for the summer Obon festival of the dead.[37]

A key component of the karakuri-ningyō’s continued resonance in modernizing Japan was their superlative craftsmanship, which expressed the Japanese notion of saiku. Meaning precision or fine skill, the term also carried the nuance of wonder. Objects displaying saiku were given traditionally to temples as votive offerings, though the popular appeal of these wondrous devices extended their presence beyond temple grounds, in the blurring of sacred and secular that is characteristic of dolls in Japan. For instance, the fifteenth-century history, Record of Things Seen and Heard, describes marvelous reenactments of battle scenes using karakuri-ningyō made by the monks of Nara (known as Nara-saiku). Yet at the same time, karakuri-ningyō were also popular items at court where they were exchanged as gifts.[38]

Karakuri-ningyō, again similar to ningyō-jōruri, followed a progression of increasing size, realism, and complexity during Japan’s modernization. Traditionally, mechanical dolls were operated by strings and pulleys that were hidden from view beneath the doll’s clothing (fig. 6).[39] This construction was revolutionized—and a new cultural form of wonder produced—by literally incorporating the foreign technology of clockwork into the body of the doll.[40] Western-style clocks first had been introduced to Japan by Jesuit Missionaries beginning in the mid-sixteenth century.[41] But it was with the larger infiltration of scientific technology brought by the Dutch over the course of the seventeenth century that Western-style clocks entered the cultural main in Japan. Among the mechanical and optical devices that constituted these new ideas, clockwork came to have a social prominence that, by the eighteenth century, was seen to exemplify a Dutch version of saiku (and indeed was referred to as “Dutch-saiku”).[42] As Screech observes, as clockwork “came to be seen as the quintessential precision mechanism, it bore an increased load of meaning until it stood generically for all cunning and advanced contrivances.”[43]

Doll bodies were the primary forum for experimenting with, implementing, and displaying the new clockwork technology—and its associated saiku. An example of a “tea-serving” karakuri-ningyō illustrates well how the fundamental operative structure of the karakuri-ningyō was overhauled (fig. 7). Instead of a simple configuration of ropes and pulleys, the doll’s body is now composed of an intricate system of wheels, levers, and springs, a system that increases the doll’s range of motion, as well as refines the quality thereof. For instance, the doll seen here could deliver a cup of tea, “walking” smoothly enough while doing so to avoid spillage; the mechanism was also sufficiently sensitive so that, when the drained teacup was replaced on the tray, its lighter weight triggered the doll’s 180-degree rotation and return to its origin. Such improved functionality generated more naturalistic movement so that the simulated human motion of the modernizing karakuri-ningyō enhanced its realism as a whole. In this way, the adaptation of clockwork technology in Japan deepened the alliance between machine and doll—and thus also that between doll and human. The wonder produced by the moving dolls can be seen in an Edo-era woodblock print of a family marveling at their own tea-serving karakuri-ningyō (fig. 8). The print also testifies to the widespread cultural commerce of karakuri-ningyō among the myriad dolls populating the Edo period.

This machine-doll-human alliance continued to strengthen as karakuri-ningyō progressively grew in verism and complexity. This development is witnessed strongly in the many theatrical exhibits of karakuri-ningyō in the Edo era. Inspired by the great public enthusiasm for the new saiku of mechanical dolls, theaters designed expressly for the performance of karakuri-ningyō emerged and proliferated, rivaling the other doll theaters of ningyō-jōruri and kabuki. The most famous among these was the karakuri-ningyō theater of Takeda Omi, who capitalized on the new doll spectacle that blended tradition and modern technology. Set up on an outdoor stage, Takeda’s works included such impressive displays as a life-sized mechanical wrestler with which the audience was encouraged to test skills.[44] As seen in a woodblock print illustrating one of Takeda’s shows, such karakuri-ningyō attractions were presented for maximal dramatic effect, grown in size and performing complex movement; the front figure here, for instance, incorporated hydraulics as well as machinery to enable it to marvelously lift its garments and “urinate” (fig. 9).

This ambiguous allegiance between humans and karakuri-ningyō was further enhanced by the fact that the clockwork technology animating mechanical dolls in itself suggested an analogue between the human body and machine. In their human (and sometimes animal) form, “the springs and wheels became metaphors for the body, with the dials and casings representing the face and skin.”[45] Moreover, the precise and intricately arranged components of the clockwork doll “entrails” worked as an integrated system. In one sense this parallel of body and clockwork increased the coherence between cause and effect: between internal generation of motion and its visible action. But at the same time, the complexity of that motion-generation tended to obscure the coherence between interior and exterior, intensifying the technical wonder of the automata.

This very inscrutability was a large part of the delight of karakuri-ningyō: the sense of there being a hidden source of agency that one could understand only partially. As Screech notes: “The charm of karakuri was that . . . their motions were exciting and viewers though half-fooled at the same time realized that there must be some explanation.”[46] Even the very term karakuri carries the connotation of being tricked or surprised. Yet the clockwork entrails were rather too obscure; for aside from their functional complexity, makers of karakuri-ningyō tried to keep the new technology under a cloak of secrecy, some even to the point of abjuring apprentices. In this sense, secrecy generated wonder out of knowledge itself; that is, the purposeful deprivation of explanatory information created an aura of mystery out of that very knowledge. In doing so, secrecy worked to heighten the tension between concealment and revelation already at play in the body of the mechanical doll. Such ambivalence is foregrounded in karakuri-ningyō theatrical exhibits that focused on the opening of the body, such as a multi-stage tableau at the Takeda Theater which displayed the development of a fetus inside the womb.[47]

As material distillations of opposing ideas and forces, it is not surprising that karakuri-ningyō also served to convey Japan’s re-interpreted traditions. Though there are many examples, the beloved figure of Hidari Jingorō was a frequent theme in karakuri-ningyō theatrical performance, just as in kabuki.[48] A woodblock print for the Takeda theater illustrates one such exhibit featuring a favorite legend about Hidari in which the famed carpenter brings to life several of his carved figures to help him with his work (fig. 10). Seated imperiously atop a double-tiered dais, Hidari is presented as the overlord of his mechanical doll assistants, who labor away below him, industriously measuring and planing wood for Hidari to vivify with his now-mechanical touch. Here, the wondrous animating power of the master carpenter is transfigured into the saiku of a mechanical doll wizard, a re-embodiment adding another layer to the doll-doubling complex in modernizing Japan.

It is interesting to observe the extent to which this intensive engagement with dolls—and their animation—permeated every area of Japan’s modernizing culture. Popular literature of the Edo era, for instance, abounds with all manner of interaction between dolls and humans (and other entities). With particular reference to karakuri-ningyō, a woodblock print illustration of a scene from Ihara Saikaku’s novel The Elegant Adventures of Maneēmon provides a telling example (figs. 11, 12). As seen in the image depicting the lead character amorously engaged, the man is distracted from the ostensible object of his pleasure by the movements of a tea-serving karakuri-ningyō in the room. Here, all reference to the doll’s mechanical structure is dissolved, representing instead a doll animated so realistically that it resembles a miniature person in the process of making tea.

Anatomical Dolls

A new type of doll emerged in the Edo era, one that influenced profoundly the direction and impact of Japan’s modern doll culture: the anatomical doll, or dō-ningyō (銅人形). Similar to the development of karakuri-ningyō, the anatomical doll metamorphosed its antecedent dolls in scale and realistic representation, in the process embodying a new understanding of the body in relation to Japanese modernity.

The year 1774 is widely held to be a key moment in the history of Japan’s relationship to modernity, as the year in which a group of scholars headed by Sugita Genpaku published the Kaitai Shinsho. Meaning “New Anatomical Atlas,” the Kaitai Shinsho was a translation of Johann Adam Kulmus’s 1731 treatise on anatomy, entitled Anatomische Tabellen.[49] As such, the Kaitai Shinsho was the first text about Western medical science to be published in Japan and eventually made accessible to a popular audience.[50]

While Western ideas were prevalent in Edo, and even the formal study of those ideas established in limited form (Rangaku, or “Dutch-learning”), the publication of the Kaitai Shinsho enabled increased pursuit of that learning, in effect “giving birth to one of the most decisive influences shaping modern Japanese history, namely the study of Western languages and science.”[51] It did so by presenting a new conception of the body based on interior inspection; in short, it introduced dissection as the essential means to obtain Western scientific medical knowledge. And in so doing, it led to a new interlinkage in Japan between modern knowledge and the body conceptualized as open, rent, and scrutinized: an anatomical body.

Such a knowledge construct was radically opposed to medical science in Japan, referred to as Kanpō. Rooted in the philosophy and practice of traditional Chinese medicine, Kanpō’s paradigm was holistic, conceiving the body as a harmonious system of energy flows and correspondences that worked in sympathy with the elements of nature.[52] Many early medical illustrations put forth this knowledge by visually describing an equivalence between the interior landscape of the body and the exterior landscape of nature.[53] Illness indicated an imbalance in the system, and was treated by herbs and acupuncture to restore the natural order. Diagnosis was performed mainly by palpation (to feel the body’s numerous subtle pulses), requiring a sensitivity of touch, not a scrutiny of vision. In sum, Kanpō’s praxis was integrative, not violative, and thus had no need to look inside the body, much less to cut it open.[54]

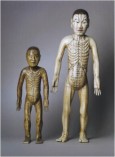

To express this body-knowledge, Kanpō used a special type of doll sometimes called keimaku-ningyō—“raised vein doll”—but more frequently called dō-ningyō, meaning “bronze doll” in reference to the material of the earliest models. The first dō-ningyō in Japan was a life-size bronze model imported from China in the Muromachi period (1392–1573); while later versions were made in a variety of materials (and sizes)—including ivory, copper, and papier mâché—they continued to be known as dō-ningyō.[55] As seen in two examples from the early Edo period, dō-ningyō are material and symbolic mappings of Kanpō knowledge onto the surface of a doll’s body (fig. 13). Canvassed by a network of lines, dots and calligraphic writing, the corporeal terrain of the doll is a visual graph of the subtle channels and nodes believed to regulate the flow of energy throughout the body. The structure and features of the dō-ningyō are schematic, subordinated to a logic of transcription whereby what is unseen (or hidden) is revealed through bodily writing. At the same time the coding is inscribed into the flesh of the doll, enlisting its material form in an interplay of surface and depth, symbol and sign. In thus coalescing the manifest and the imaginary, the dō-ningyō produces a multiply “legible body,” at once resonant object and metaphor.[56] And as an embodiment of the Kanpō worldview, the dō-ningyō was microcosmic, “project[ing] the body upon the universe and the universe upon the body.”[57]

Of course, the dō-ningyō also carried the resonance of Japan’s traditional beliefs pertaining to objects, whose quality of imminence intensified the doll’s symbolic claim to personhood. Tacitly linked through resemblance to the totems and effigies of Japan’s traditional doll-world, the dō-ningyō resonantly embodied the nebulous bordering between the living and the dead. It bears noting here the dō-ningyō’s alternate relationship to death. The first recorded dō-ningyō was made in the Han dynasty, modeled after the corpse of a criminal whose dissection was ordered expressly for the purpose. Known originally as a tongren (in Japanese dōjin or “bronze person”), it was the progenitor of all subsequent dō-ningyō in China, Japan, and Korea.[58] At least in this one sense similar to their Western counterparts, the study of medicine in Asia was predicated on death. Significantly, it was another corpse that gave birth to the anatomical dō-ningyō. For it was viewing a human dissection in 1771 that first inspired Sugita Genpaku and his collaborators to translate the Kaitai Shinsho.[59]

Dō-ningyō were instrumental in the “world-making” of the anatomical body. Through a process of mutual influence, dō-ningyō proliferated as the new medical science spread, and were circulating widely by the mid-eighteenth century.[60] As most models were produced in Europe, Westernized features accompanied a dramatic change in form. As seen in a life-size bronze model from the seventeenth century, the rudimentary human figure of the earlier dō-ningyō has metamorphosed into a naturalistic human form, replete with articulated musculature (and European features; fig. 14). But more significant is that the doll opens; the toggles to either side of the lower ribs attach to hinges, allowing the “door” of the belly to open and the viewer to look into and examine the neatly arranged internal doll organs. And yet, the earlier system of body-mapping has not disappeared. Though the painted lines are absent on this model, the constellation of vital points is still present, overlaying the dermal topography of the doll. The new (and still-evolving) dō-ningyō had become a hybrid microcosm.

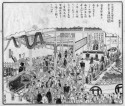

Traditionally, medical knowledge was exchanged through the popular exhibitions of “materia medica,” or bussan-e, held periodically throughout Japan from the middle of the eighteenth century.[61] As Wolfgang Michel has observed, lacking “universities or museums, these events were instrumental in establishing a common base among professionals and accelerating the exchange of information and objects.”[62] As seen in a woodblock print of a bussan-e, among the mélange of objects, animals, and specimens, two dō-ningyō are given pride of place, as well as theatricality, on a raised platform set apart from the crush of people (fig. 15). Before an elite audience who gaze up at the spectacle, the dō-ningyō are presented as live performers on a stage, even to the positioning of one in the manner of a seated official. Here the rhetoric of political and scientific authority conflate in the wondrous body of the anatomical doll, thus complicating its already-charged object-resonance.

The modern magic of the dō-ningyō could not stay long confined to the sphere of the medical establishment, but became a spectacle in and of itself. A free-floating material signifier, dō-ningyō travelled among the many misemono, or large urban street fairs, where they accrued additional meanings. A woodblock print from an 1818 anthology of misemono shows a dō-ningyō performing its secular wonder amid the crowded bustle of commerce and attractions. Still seated authoritatively, with its entrails open to view, the scientific doll is fully absorbed into the urban landscape of Edo life (fig. 16).

Dō-ningyō also entered the popular discourse surrounding the new science, or what Timon Screech describes as “the anatomical demotic.”[63] A dominant strand of this discourse associated the dō-ningyō with violence, a natural connection given that the anatomical knowledge configured by the doll derived from dissection. But its unfamiliarity and perplexing logic (relative to that of Kanpō) led dissection to be associated with gratuitous violence and a consequent fascination with gore. This no doubt was amplified by the fact that corpses supplied for autopsies were those of executed criminals, and the pain inflicted on the bodies seen as a continuation of juridical punishment.[64] In this way, civil, penal, and scientific discourses were enmeshed in the new anatomical body.

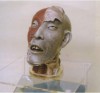

A dō-ningyō owned by high-ranking physician Katsuragawa Hōshū strongly evidences this punitive violence associated with dissection and its multiple resonances (fig. 17). Consisting only of a head, Hōshū referred to his model metonymically as his “Captain Waxman” in reference to the wax material of its composition.[65] The intense realism of the doll-head, with its flayed, putrefying flesh and grisly expression, directly echo the decapitated heads of criminals depicted in contemporaneous dissection imagery. In this context, both as an isolated head and as a prize of an imperial official, the dō-ningyō recalls the military practice of ritually presenting the dismembered head of an enemy leader to the victor.[66] As such, the anatomical dō-ningyō instantiates the resonances of criminality, scientific virtue, and political trophy, producing a site multiply resonant and wondrous.

The dō-ningyō continued in a trajectory of growing naturalism, as can be seen in the anatomical dō-ningyō dating from 1860 (fig. 18). Fabricated for the purpose of instruction at the new medical schools, the life-size figure is no longer rigid and frontal but stands in contraposto posturing and attitude drawn from European classical antiquity. Its composition assumes scientific knowledge of the skeletal and muscular structures of the body. The figure’s material of papier mâché similarly employs the European fabrication method of anatomique plastique, made famous by the French physician Louis Auzoux.[67] Fully anatomized, the dō-ningyō has evolved into a modern medical doll, the symbolic veins of the original raised-vein doll now literalized and fully visible traversing the skinless doll-body. Still, the anatomical doll did not replace prior forms of the dō-ningyō, but rather co-existed with them as simultaneously re-articulated bodies of knowledge.

Through the examples of the mechanical doll and the anatomical doll, we see how Japan’s dolls were strategically employed to materially interpret and coalesce new concepts and technologies with pre-existing beliefs and practices. The evolving hybridity of these dolls instantiated Japan’s modernizing process, just as it amplified the enigmatic resonance of the dolls themselves. This hybridizing evolution of Japan’s modernizing dolls reaches a pinnacle in the “living dolls” that emerge fully and flourish in Japan’s high modernity.

III. Living Dolls: Being Modern in Japan

On February 2, 1852, the craftsman Oe Chubei opened an exhibition of dolls in the Naniwashinchi entertainment district of Osaka. Evidently believing his work to represent a new standard in dolls, Chubei proudly entitled his exhibit Imayo ningyō daihō nenjū ni no nigiwai or,“Modern Dolls For This Year of Prosperity.”[68] The numerous dolls in the display depicted popular actors of the Osaka Kabuki stage captured during peak moments of performance; these showed recognizable characters in typically dramatic poses with facial expressions filled with intense emotion.

But kabuki dolls were not in themselves new in the doll-saturated culture of Edo. As noted above, the doll-theaters of ningyō-jōruri, karakuri-ningyō, and kabuki dominated the Edo era, and dolls modeled after those of the doll-theaters were produced in great numbers. Chubei’s dolls, however, were distinctive in two important respects: their scale was fully life-sized, and their manner of rendering was extremely realistic. In fact, his dolls bore such startling resemblance to their living human counterparts that astonished audiences hailed them as iki-ningyō or “living dolls.”[69] From this moment forward, the modern doll was synonymous with the ultra-real in the Japanese cultural imaginary, ushering in the full-scale enactment of Japan’s modernizing technique of producing mimetic wonder.

Realistic Resonances

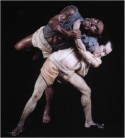

Chubei’s dolls no longer survive, but a later example serves to demonstrate what was new about iki-ningyō. A life-sized iki-ningyō of two sumo wrestlers engaged in athletic combat conveys something of their dramatic impact (fig. 19). Poised on the precipice of decisive action, the interlocked figures struggle violently against one another, muscles taut with strain and faces riveted with the intensity of their exertion. The asymmetrical disposition of the conjoined figures forms a dynamic composition that intensifies the narrative drama in which the figures are embedded, as do the complex distributions of visual weight between the axially configured doll bodies.

The emphatic expression of the wrestlers is characteristic of iki-ningyō and is achieved through a paradoxical combination of extreme detail and large scale. The sheer size of the doll produces an arresting physical presence that projects outward into the viewer’s space. At the same time, that presence is amplified by increasingly fine degrees of detail that draw the gaze inward: from the careful modeling of the musculature to the fine textures and colorings of skin, to the glass-inset eyes, individually-shaped teeth—even to the strands of individually inserted, real human hair. All is rendered to achieve a maximum fidelity that is at once confrontational and seductive. In effect, the doll operates in both directions at once, provoking a somatic response on the level both of impact and of intimacy. In this sense, the very materiality of the doll emulates the oscillations—or simultaneity—of wonder and resonance, producing a richly enigmatic aesthetic.

The human verisimilitude of the wrestlers clearly draws from earlier technologies of doll-making, in particular those of the karakuri-ningyō and the dō-ningyō. The ability to construct figures that appear to respond realistically to the forces of gravity reflects an anatomical understanding of the skeletal and muscular structures of the body. Likewise, the intense realism that characterizes the iki-ningyō’s expressiveness—its detail and handling of material—can be traced to practices of medical dissection and model-making. Similarly, a great many iki-ningyō utilized the mechanical technology of the karakuri-ningyō to add actual movement to the motion already implied by the verisimilitude of the dolls. As well, the construction methods of iki-ningyō were based on a unique combination of technological innovations and traditional techniques of doll-making. Typically these employed either papier-mâché or plaster built up over a wooden core that was then covered with gofun, a traditional material made from oyster shells. Like wax, gofun is pliant when wet and can be modeled, pigmented, then textured or polished.[70] But the iki-ningyō integrated these methods to produce a new type of wonder that epitomized the modern world-making process begun with the earlier dolls.

Wondrous Evolution

The modern iki-ningyō did not appear instantaneously, but, rather, developed over the previous several decades in conjunction with misemono, or the street fairs that formed an integral part of the urban fabric of Edo. Set up along major thoroughfares, or inside the grounds of large temple compounds, misemono consisted of amusements, attractions, and shows of all manner and variety. These were enormously popular events, drawing huge crowds from all levels and areas of society. And though their commercialism tended toward the bawdy and exploitative, misemono set the pulse of Edo, forming an essential space in which new ideas were introduced to a broad populace. In his important study of the misemono, Andrew Markus remarks on the critical function of the misemono to Edo life as “an inalienable part of the Japanese urban landscape for two hundred years at least; their popularity extended to all strata of society; their oddities and marvels were a favorite topic of scandal sheet and scholarly disquisition alike, and inspired the author and printmaker.”[71]

The notion of saiku featured strongly in misemono fare. As noted above, saiku referred technically to fine craftsmanship but carried the nuance of novelty, and especially wonder. Originally applied to religious offerings, over time saiku became objects of display in their own right and thus came to be featured as much in secular as in sacred contexts.[72] In terms of misemono, as Andrew Markus observes, saiku was “at the core of a great many attractions” where it “inclined either to very finely detailed craftsmanship, or to artisanry on a megalomaniacal scale.”[73] For instance, the former could be observed in a recreation of an entire row of shops, simulating to the minutest detail every feature of the vegetables, flowers, and bonsai plant “merchandise” on display. More typical, however, were saiku displays of “grandiose size and ostentation”[74] such as a 159-foot tall Vairocana Buddha composed of oiled paper featured at a temple opening in 1798. Other notable saiku of the monumental variety included a velvet toad of colossal proportions, a 22-foot tall embroidered sculpture of Daikokuten, the god of prosperity, a gargantuan Dutch ship constructed of glass, and a tableau of the “24 Paragons of Filial Piety” fabricated from dried kelp.[75]

Human-dolls were an important component of misemono saiku. Dolls prefiguring the modern iki-ningyō appear as early as the turn of the nineteenth century, as evidenced in records of large-scale doll exhibits held at the Asakusa Sensoji temple complex. As Markus observes: “Still figures of varying dimensions, alone or in tableau, were a reliable source of revenue for exhibitors.”[76] Their emergence and development at this time is significant because it occurs in tandem with that of the misemono itself, which increased dramatically in frequency and size after 1800. Further, as Alan Scott Pate has remarked, throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the many misemono in the capital “invariably featured iki-ningyō among its star attractions.”[77]

But Chubei’s dolls mark a watershed moment in the social history of the iki-ningyō. Judging by their popular description as “living,” it was their ultra-realism that distinguished the dolls from their predecessors. By the same token, it was that same ultra-realism that evinced a strong response from the viewing audience and captured its imagination as wondrously “modern.” Indeed, Chubei’s dolls were new sites of resonance and wonder combined; “living” embodiments of a newly mimetic, modern microcosm, his dolls synthesized the misemono saiku’s dual propensities toward detail and ostentation, in doing so re-defining the human-doll blend in a distinctly “modern” way. Characterized by realism, large scale, and embedded narrative, the dolls also synthesized tradition and modern technologies. In sum, they were paradoxical and excessive, or enigmatic, marvels.

From Chubei’s exhibition forward, the modern doll, already a staple since 1800, was embraced with renewed enthusiasm that continued well into the twentieth century. Moreover, as Markus notes, the 1850s and 1860s were a time of great flourishing for the iki-ningyō,[78] becoming so embedded into the cultural imaginary as to be the very hallmark of Edo itself. This national stardom of the modern human-doll is perhaps best expressed in a contemporaneous late-Edo senryu, or comedic poem, which identified three signature products (meibutsu) of Edo, these being fire, kaichō (temple fairs) and iki-ningyō.[79]

Enigmatic Contexts

Kaichō themselves were intimately connected with iki-ningyō, being the favored venue of misemono exhibitions. The term kaichō refers to temple fairs, literally temple openings, during which an auspicious icon or relic normally kept hidden from view would be placed on public display for a limited time.[80] Lasting variously from a few days to several months, kaichō were major festive events that generated revenue for the sponsoring temple or shrine, and thus functioned as commercial as much as religious affairs. As such, kaichō were target sites of misemono, which not only benefited from the immense and concentrated patronage of kaichō, but whose own temporary displays of wonder—in particular the iki-ningyō—paralleled those of the temple, and in doing so drawing crowds that worked to the financial benefit of both.[81] The kaichō, and with it the iki-ningyō, was thus characterized by a distinctive conflation of the sacred and the profane. As Andrew Markus has observed of this mutual interpenetration of kaichō and misemono operations:

Thousands lined streets and riverbanks to welcome such [sacred] images to Edo in processions . . . tens of thousands crowded temples during the term of the kaichō. Religious sentiment motivated many pilgrims, but just as many visitors no doubt sought first of all the showmen’s booths in which wonders of a very different sort—secular counterparts, perhaps, to the sacred artifacts on temporary exhibition—were accessible for a few small coins.[82]

As events officially dedicated to unveiling what normally was hidden, the kaichō’s operative principle was revelation. Consequently, its dynamic of strategic hiddenness conferred upon disclosed objects the aura of marvels. As we have seen, iki-ningyō were in themselves already rarified sites of the marvelous, both visually revelatory and mysterious at the same time. That is, while their realism pledged the fullest disclosure, the technologies enabling that realism—be they mechanical or anatomical, or both—remained inscrutable. Thus the very context of display, in its blurring of oppositions, doubled the embodied tensions of the iki-ningyō, and amplified its enigmatic dynamism.

Iki-ningyō further played up the theme of revelation through the subject matter they depicted. They did this frequently by mirroring in a worldly context the religious disclosure of the temple images. For example, an 1855 iki-ningyō exhibit entitled “Inner Secrets of a Brothel” revealed the normally closed world of elite private entertainment and its shrouded human icon, the courtesan. As seen in a print reproducing this popular exhibit, a behind-the-scenes narrative unfolds to show various inhabitants of the cloistered demi-monde engaged in their daily routine (fig. 20). At the center of attention is the celebrated figure of the courtesan, not only whose lifestyle is exposed to view here, but her body as well: her white doll-flesh awesomely unveiled to the public gaze. Usually cloaked in secrecy, the pedestrian activities of the brothel figures are energized with the magical appeal of novelty, a quality no doubt amplified by the automated motions of the mechanical dolls. This scene is one of many tableaux composing the entire brothel exhibit, which comprised sixty-two life-sized automata in all.[83]

A similar exhibit that same year was more overtly revealing, as well as topical. It featured a famous courtesan of the Maruyama entertainment district of Nagasaki in a bathing scene with other beauties (fig. 21). A rare photograph from the display shows the life-sized mechanical doll sitting naked, freshly emerged from her bath and smiling in a graceful attitude while grooming herself (fig. 22). Made by Matsumoto Kisaburo, successor to Oe Chubei and one of the undisputed masters of the iki-ningyō, the Maruyama beauty evidences the sculptural and narrative realism for which the iki-ningyō was renowned.[84] Itself a marvel, the iki-ningyō in such narrative scenes created multiple layers of revelation that increasingly made fluid the boundaries between sacred and profane, animate and inanimate, human and doll. The many print images representing these and other iki-ningyō scenes not only attest to the public’s fascination with the “modern” dolls, but act themselves as another kind of doll-proliferation in the modernizing mass culture of late Edo, as well as Meiji, Japan.

Iki-ningyō explored revelation also in terms of interior states of mind disclosed in the manifest form of the body. An 1857 iki-ningyō tableau at the Ekoin temple, for instance, depicted 100 women “of all ages and stations, their faces the embodiment of as many different emotions.”[85] More explicit treatments of bodily revelation occurred in such popular exhibits as the 1864 “Ten Months of Pregnancy,” in which large-scale models of an open uterus displayed the progressive gestation of a fetus.[86] Here we see the sacred and profane spectacle of the misemono overlayed with the scientific wonder of the anatomical doll. In the context of the kaichō, the interior of the human body became a microcosmic space of carnal and medical magic whose hidden generative potential, disclosed via spectacle, collapsed the paradigms of old and new cosmologies in the body of the doll.

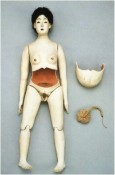

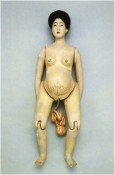

Several extant small-scale versions of misemono “pregnancy dolls” provide descriptive information about the iki-ningyō exhibits, as well as reiterate the ubiquity of dolls and of doll-doubling in the Edo and Meiji eras. As seen in two examples, the same attention to realistic detail is applied as in the large-scale dolls, from the delicate features and skin colorings, to the careful renderings of the fetus and organs that fit precisely inside the body cavity (figs. 23 and 24). By its combined focus on explicit anatomy and realistic human rendering, the pregnancy doll also demonstrates dramatically the evolution of the iki-ningyō; in particular, the articulation of the limbs visible in these small models is a direct result of anatomical knowledge applied to the doll. The miniature scale of these examples also transforms the wonder of their large-scale counterparts to the realm of the commodity; for all its complexity, as a hand-held “marvel” the doll is subject to easy control and manipulation: portable, mini-worlds to be disassembled for haptic scrutiny. In this sense, as a derivative of the larger cosmological body of the iki-ningyō, the diminutive version suggests the distortions to which such bodies are prone.[87]

Iki-ningyō enacted revelation on a deeper level still by doubling the very icons on display during the kaichō, as well as other religious figures associated with the temple. For example, two photographs show an iki-ningyō scene depicting the legendary figure of Shoki, the queller of demons in popular folklore, and arbiter of hell in Buddhist mythology; [88] sitting cross-legged on the floor, Shoki is attended by a female figure who shaves Shoki’s forelocks while standing upon one of the demons he has subdued (figs. 25, 26).[89] Particularly evident in these images are the lustrous skin tone and expressive facial features that vivify the iki-ningyō beyond their naturalistic modeling and automated movements. By these visceral re-animations of religious figures, the iki-ningyō became themselves material sites in which the sacred and profane—as well as old and new, tradition and modernity—were enigmatically blended, thus complicating and intensifying their status as resonantly modern wonders.

Such amorphous meldings reached perhaps the ultimate climax in a tour-de-force of iki-ningyō history: Matsumoto Kisaburo’s life-sized mechanical iki-ningyō display of the Buddhist deity Kannon. Designed for the Asakusa temple as part of an 80-day kaichō, the lavish production presented over seventy-five figures in a series of vignettes that enacted the miraculous stories of the goddess of mercy as she traveled to each of her thirty-three pilgrimage sites.[90] The graceful and sinuous lines of the Kannon figure convey a superlative vitality that is echoed in the folds of her sumptuous silk garments as they cascade rhythmically down her doll-body (fig. 27). Likewise, the lilting head-turn and delicate gestural curves of the elbow and hand communicate a marvelous quality of subtle motion. As well, the glowing complexion and exquisite facial features—including individual ivory teeth and glass-inset eyes—exude an expression both serene and beguiling whose total effect is captivating.

The Kannon doll is without doubt a virtuosic display of iki-ningyō fabrication. Intriguingly, Matsumoto was of the very same opinion, finding his creation to embody so perfectly the essence of the famed Buddhist deity that he donated the doll to the Jokoku-ji temple in his hometown of Kumamoto. As an examplar of modern Japan’s conflation of the sacred and the profane, the doll-icon resides to this day at Jokoku-ji “as an object of veneration.”[91] In its place to appear in the kaichō, Matsumoto made another iki-ningyō of the Kannon figure: a doll double. Originally unveiled in 1871, the elaborate exhibition of the Kannon-double visiting her thirty-three pilgrimage sites was the “prize attraction” of the capital, so popular that it ran for nine years in succession.[92]

Marvelous Nationhood

In addition to the bodily reiteration of deities and living persons, iki-ningyō also doubled figures from history, literature, and legend. For instance, another renowned iki-ningyō maker, Yasumoto Kamehachi, produced in 1857 a reenactment of the medieval legend of Chushingura; iki-ningyō set in a series of tableau materialized the famous narrative of 47 roaming samurai.[93] His 1871 monumental re-creation of the 53 stations of the Tokaido Road was even more stunning to Osaka viewers.[94] Amid the misemono’s ambiguous configurations of place, space, and function, these material recapitulations conflated temporalities as well, conjuring an enigmatic present at once palpably immediate yet also redolent with mythic and historical time past. Further, by instantiating history—imagined as well as actual histories—these doll incarnations of the past served to reinforce and validate a collective narrative of Japanese culture. For instance, considering again the Tokaido Road display, it becomes clear how the mandated annual journey of daimyō to pay tribute to the Emperor—stopping at each of the 53 policed stations en route—is re-inscribed in the iki-ningyō body as a marvelous cultural heritage: a source of collective identity as much as wonderment and delight.

In this regard, some of the most poignant examples of the iki-ningyō’s historic re-animations were modeled from the text Chinsetsu Kidan Ehon Bankokushi, or “Illustrated Strange Tales and Wonderful Accounts of the Countries of the World.” First written in 1772, and updated in 1826, the book is a fantastic but telling history of Japan’s self-conception as a people.[95] Here, as in the misemono context, modalities of space and time are blurred together in an imagined locus of Japanese identity. Japan is envisaged situated at the center of the world from which other countries radiate outward, their inhabitants increasingly inscrutable in proportion to their distance from Japan.

Significantly, this geographically determined unknowability of foreign beings is correlated to physical abnormalities.[96] An 1855 woodblock print by Kuniyoshi, for instance, shows an iki-ningyō display featuring figures incongruously combined from the “Land of People with Long Arms” and the “Land of People with No Stomachs” (fig. 28). As though the bizarre physical attributes of the doll-foreigners were not spectacle enough, the exotic otherness of the scene is accentuated by the mountainous terrain, another geographic signifier of cognitive distance.[97] More flagrant still is the untoward dispositions of the creatures and the clearly Sino-fied facial features.

The iki-ningyō displays modeled after the “Strange Tales” and other accounts of foreign lands are especially vibrant in relation to Japan’s burgeoning high modernity in that they fostered a tacitly racial group identity by othering the ethnicities of non-Japanese peoples.[98] In this sense, as three-dimensional models that portray racial characteristics, such iki-ningyō displays also operated as ethnographic exhibits—an especially distinctive phenomenon, as the Western concept of ethnography per se, and its representational milieu, had not yet been fully formed, much less interacted with Japan’s modernity. This manifest alliance of collective identity and ethnographic logic is significant in showing again the enigmatic quality of the iki-ningyō, as well as enunciating its adaptability and effectiveness in serving the purposes of modern nationhood.

Further, the geographical underpinnings of the “Strange Tales” and their doll-displays implicate the shifting of Japan’s ideological borders, which, as Tessa Suzuki-Morris has shown, is crucial to the construction of nationhood. As she writes: “The creation of nationhood involves not only the drawing of political frontiers but the development of an image of the nation as a single natural environment or habitat.”[99] Likewise, this constructed allegiance is supported by establishing narratives of ethnicity.[100] Here it is interesting to observe the enigmatic power of the iki-ningyō and its context at work; despite the centrist logic of the “Strange Tales,” the doll-rendering of foreigners ironically re-locates those peripheral figures to the imaginary center of Japan’s world-making practices: the misemono, where the doubles of foreigners mingle in wonder with the marvelous doubles of deities, nobles and commoners alike.

Finally, amid these nationalizing re-inscriptions of Japan’s traditional ideas into doll bodies, the figure of Hidari Jingorō and his living doll remained a vital phenomenon. A woodblock print produced in 1898 illustrates the continuing force of this figure, and of its culturally embedded principles of object animation and of the interpenetration of sacred and secular spheres (fig. 29). Seated on the floor in an attitude of rapt admiration, Hidari Jingorō gazes upward at his living doll—now fully life-sized—in the moment of imminence before the doll actually moves and speaks. The doll’s radiant animation, achieved by Hidari’s bravura realist technique, recapitulates visually Japan’s modernization as manifested through its intensive engagement with dolls.

In these many ways, we see how the iki-ningyō emerged as the technological and ideological apex of its doll-precursors, and how its enigmatic resonance was augmented in the misemono’s characteristic blurring of structural and perceptual modalities. And from within this charged environment, the iki-ningyō performed the re-constitution of Japan’s knowledge-practices, fostering and inculcating Japan’s modern identity as a nation thereby.

Conclusion

Modernities are ideological as much as political and technological configurations. Though intangible and malleable, the collective ideas of modern imaginaries contour, empower, and mobilize national allegiances with a facility at least as great as that of more visible social machineries. Techniques used to shape ideology thus figure crucially in modernizing agendas and the world-making enacted thereby. This is especially true, and especially fraught, in the leveraging of its dolls in the making of Japan’s modernity.

As we have seen, dolls served as critical sites through which Japan confronted the tensions and anxieties engendered by its encounter with the new and foreign. Doll bodies were the testing grounds for new technologies: physical loci through which new ideas were materially processed, interpreted, and concretized. The alacrity with which Japan’s doll designs continually evolved testifies both to the dynamic power of knowledge practices and to the instability of media technologies, within the social economy of those practices.[101]

In thus bearing witness to Japan’s modernization, doll bodies interfaced the melding of old and new cosmologies. The animistic affiliations of Japan’s historical dolls converged with the modern rhetoric of medicine and machinery to produce newly enigmatic sites of bodily wonder. These doll-imbrications of old and new paradigms speak to the persistence of the sacred amid the modern. As Barbara Maria Stafford has observed: “The typically modern, 'Enlightened’ association of technology with secularization tends to overlook its historical role in materialization of the sacred.”[102] Stafford’s comment is directed toward a European context but applies equally, if not with extra force, to Japan, where mythic and modern beliefs intermingled and blended through the various articulations of its modern dolls.

Japan’s dolls performed likewise as auratic sites of national inscription: bodies in which narratives of the nation overwrote their magical resonances. These embodied palimpsests of modern wonder distilled and purveyed Japan’s modern world-making to a nationalizing collective. Moreover, these same objects transplanted abroad a Japanese modernity indelibly associated with dolls.

In this light, it is well to return to the dolls given to Commodore Perry, and to the questions posed at the outset of this essay. After the investigation undertaken here, the initial question now is not so much why dolls were presented to the Commodore at all—for the evident cultural value of dolls in Japan justifies fully their presence as gifts of state—but rather why the type of doll was given.[103] Indeed, given the tremendous cultural prestige and signification of Japan’s modern dolls—in particular the karakuri—why were they not chosen instead? This seems especially odd to consider that the comparatively humble gosho dolls were each under four inches tall.[104] Indeed, if the gosho type of doll was chosen to exhibit traditional skills as much as associations, far more visually impressive models abounded.[105]

Given that the Kanagawa negotiations were undoubtedly undergirded by hostility, it is interesting to speculate as to the reason for the purposeful doll selection. It is true that the gosho doll’s imperial association made it appropriate to the official occasion, and ostensibly demonstrated Japan’s respect toward the commodore. However, in view of the issue just raised in regard to the inferior cultural status of the gosho relative to mechanical and “living” dolls, the integrity of that intention becomes less assured. The symbolism of the dolls’ various attributes is instructive here in that the tension-filled context of the gift exchange casts a certain ambivalence on their otherwise benevolent meanings. The doll in figure one, for instance, holds a gourd on which is depicted a turtle bearing the words kin ōshō (金王将), or “gold general” (fig. 1). In the game of shōgi (将棋), gold generals are chessmen of high rank who “retain their rank throughout the game and are guarded by other pieces.”[106]

As for the more important question of what the doll gifts portended for Japan’s modernity, I suggest that they adumbrated what would quickly become a vibrant and multi-streamed inter-cultural commerce helmed by Japan’s dolls: a commerce that contributed vitally to the making of multiple imaginative and institutional modern worlds, both in Japan and abroad. The dolls given to Commodore Perry, along with the other objects received from Japan during the Treaty signing, eventually came to constitute the founding collection of the Smithsonian ethnographic museum.[107] Thus the auspicious gosho presaged the flow of protean doll iterations from Japan, highly enigmatic bodies that made frequent appearances in such venues as international exhibitions, department stores, art museums, ethnographic displays, and theater productions, each doll a rich and resonant material voice speaking to the ongoing transitionality of Japan’s modernity.

I am indebted to Professor Gennifer Weisenfeld for her support and incisive guidance on this project, as well as to Dr. Kristina Troost for her library expertise. I would like also to thank Yuji Tanaka at the Edo-Tokyo Museum for kindly sharing with me valuable information, as well as Dr. Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, and the anonymous reader, whose critical feedback led to a greatly improved article.

[1] See Chang-su Houchins, Artifacts of Diplomacy: Smithsonian Collections from Commodore Matthew Perry's Japan Expedition (1853–1854) (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995).

[2] Tokubei Yamada, Shinpen Nihon Ningyō-shi (Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten, 1961), 233.

[3] Ibid., 30.

[4] Nelson Goodman, Ways of Worldmaking (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1978), 6. These quotes refer to Goodman’s theory of “worldmaking”; as he writes: “Worldmaking as we know it always starts from worlds already on hand; the making is a remaking.”

[5] Stephen Greenblatt, “Resonance and Wonder,” in Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, ed. Ivan. Karp and Steven. D. Lavine (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991), 42.

[6] Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 31.

[7] Michel de Certeau speaks variously of the interweaving of objects and their shifting significations into our understanding of everyday life. Michel De Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), esp. chap. 7 “Walking in the City.

[8] I refer to Appadurai’s theory of “the social life of things.” Arjun Appadurai, The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

[9] I am using the term supplement in the Derridean sense of a copy’s ambiguous relationship to the original. See Jacques Derrida, Dissemination (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993). See also Jacques Derrida, On Grammatology (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1998).

[10] Michel Foucault, Ethics, Subjectivity and Truth (Paris: Gallimard, 1994), 87, 89.

[11] Homi K. Bhabha, Nation and Narration (London: Routledge, 1990), 1.

[12] Stefan Tanaka refers to “the materiality of ideas” in relation to his interrogation of the temporal shifts that he sees to be fundamental to Japanese modernity, and how those shifts find manifest expression in various social and cultural forms. Stefan Tanaka, New Times In Modern Japan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), ix.

[13] It is worth noting the disparity in meaning and usage between dolls in Japan and in the West, since it can be observed that dolls were also prominent in the modernities of Europe and the Americas. Western dolls, however, and especially in the modern period, belong to a specific class of objects as well as to a delimited social sphere. Interestingly, just as the Japanese word for doll opens its meaning, the words for doll in European countries circumscribe its meaning. For instance, poupée in French and puppen in German, are diminutively inflected, registering semantically the social relegation of dolls to the domain of children. Morever, European languages have numerous terms that distinguish clearly among various types of figurative objects. These are classifications that, for the most part, also indicate the scale, as well as the contexts for, and manner of engaging with, the object. Consider, for instance, such terms as sculpture, figurine, icon, mannequin, puppet, and anatomy model, none of which had parallel categories in Japan during the period under discussion. For a general history of dolls see Max Von Boehn, Dolls and Puppets, trans. Josephine Nicoll (London: George G. Harrap and Company, 1932).

[14] Yamada goes on to specify that Buddhist figures, while fitting the definition of doll he has offered, generally should not be regarded as dolls because of their purpose to represent a deity. Yamada, Ningyō-shi,12–13.Even this distinction between doll and, what in the West would be termed icon, is fluid.

[15] As he writes, “there is hardly a contemporary Japanese household that does not have a doll case.” Ibid.,12. For examples within the larger context of contemporary Japanese household practices, see Inge Maria Daniels, “The 'Untidy’ Japanese House,” in Home Possessions, ed. Daniel Miller (Oxford: Berg Publishing, 2001), 201–29.

[16] See Sokyo Ono and William P. Woodard, Shinto: The Kami Way (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2004).

[17] For a discussion of the complex role of objects in Japanese Buddhism, see Fabio Rambelli, Buddhist Materiality: A Cultural History of Objects in Japanese Buddhism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007).

[18] Robert H. Sharf, “On the Allure of Buddhist Relics,” in Embodying the Dharma: Buddhist Relic Veneration in Asia, ed. David Germano and Kevin Trainor (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2004), 171. For a discussion of the animate status of Japanese Buddhist icons more generally, see Robert H. Sharf and Elizabeth Sharf, eds., Living Images: Japanese Buddhist Icons in Context (Stanford: Standford University Press, 2002).

[19] As Rambelli explains, “Buddhism can thus be understood…as a complex way of interacting with “material” objects to achieve some “spiritual” goals.” Rambelli, Buddhist Materiality, 3.

[20] Akira Y. Yamamoto, Introduction to Japanese Ghosts and Demons: Art of the Supernatural, ed. Stephen Addiss (New York: George Braziller, 1985), 13. See also Angelika Kretschmer, “Mortuary Rites for Inanimate Objects: The Case of Hari Kuyo,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 27, no. 3/4 (2000): 379–404. For example, tsukumogami, or “tool specters,” are animate household instruments that first appear in literature of the Heian period. Such beliefs about tsukumogami are continued in the present-day practice of susuharai, the ritual house cleaning that occurs at each year-end. If not properly discarded, the tools are thought to become polluted and capable of malice toward their users.

[21] See Rambelli, Buddhist Materiality, 211–58.

[22] Ibid., 211.

[23] Ibid., 221.

[24] See ibid., 211–58 for a full discussion.

[25] As he observes, “dolls since ancient times functioned as ritual implements and magical objects.” Ibid., 232.

[26] Ibid.